CHAPTER 8

The Early Anglo-Saxon Framework for Middle Anglo-Saxon Economics: The Case of East Kent

Stuart Brookes

Introduction

Recent contextual approaches to Early Medieval socio-economic development have stressed the important relationship between trade or exchange and political power in the formation of increasingly hierarchical structures of social dominance. Given the dearth of archaeological evidence for the nature of these early changes, such approaches are marked by the application of social theory to numerous multi-disciplinary lines of argument, to model wider developments on the basis of recognised social features. As such, the identification of seemingly specialised commercial or trading settlements (wics or emporia) during the seventh century, has been linked to wider theories regarding the increasingly centralised economic and political power of emergent polities during this period (for example Hodges 1978; 1988; 1989a and b; Arnold 1988; Carver 1989; Scull 1992 and 1993).

In part fuelled by the importance of such trading sites and imported artefacts in archaeological literature, many interpretations of the social processes during the period have privileged the competitive exchange and consumption of foreign exotica as a causal dynamic to institutional change. The distribution pattern of these objects has been argued to represent a ‘prestige-good exchange’ apparatus operating between the kinship-dominated societies of the Early Anglo-Saxon period. As gift-giving and loyalty in military service formed the basis of social relations, a monopoly of the trade in luxury goods ensured political dominance within the competitive peer-polities. The coastal zone (including Kent, the Thames Valley and the East Anglian headland) in which these objects are primarily clustered, and the evolutionist models proposed by analogy with the later emporia sites within this geographical area, have combined to emphasise early Kentish material within macroeconomic interpretations. In part explainable by the inevitable shipping patterns around the East Kent headland, Kent has historically been presented as the focal node of impact for diffusionist patterns of settlement, trading connections, state formation, and Christianisation. Certain documentary sources attest to an East Kent/Frankish connection, in the form of Frankish claims of authority over Kent, royal alliances and tribute extraction (Wood 1983), and these have often been utilised to explain the particularly dense patterns of imported goods in the county in the Early Anglo-Saxon period (Huggett i988; Welch 1991). Additionally, some evidence for inter-regional trade is supported by eighth-century toll remissions at the ports of Sarre and Fordwich (Kelly 1992). Despite little concrete archaeological evidence for comparable trading settlements therefore, Kent has often been presented as the first kingdom to adopt monopolising control over long-distance trade, a move that placed the sixth-and early seventh-century kingdom in a pre-eminent position over its neighbours.

Such models of Early to Middle Anglo-Saxon socio-economic development suggest a number of further areas of investigation. The reconstruction of the spatial framework of increasing inter-(and by implication, intra-) regional trade and exchange suggested by the works of Hodges for example, can be explored both through the distribution of commodities in space (Renfrew 1975 and i977) or the arrangement of hierarchies of settlement with respect to the tenets of central-place theory (Davies and Vierck 1974; Arnold 1988, Fig. 5.5; Aston 1986). Carol Smith’s (1976) thesis on regional economic systems, from which Hodges drew much inspiration, also showed through a number of empirical studies, that the regional organisation of hierarchical central-places was crucially tied to modal networks, particularly in disarticulated, periodic market systems (ibid., 26). Following Stine (1962), Smith argued that, within a predominantly agrarian economy, traders need to be mobile in order to maximise the consumer demand range beyond the minimum range of goods traders need to offer to survive. Periodic markets, fairs and other specialised centres by their very nature therefore, are tied to trader mobility. Sedentary commercialised settlements, Hodges’ ‘type B’ emporia, could only occur when the consumer range increased enough to support permanent traders. These sites, be they emporia, inland settlements or markets, are expected to occupy key nodal positions within a region; straddling environmental zones, major routeways and frontiers, to maximise the demand catchment-area (Hodges 1989a, 52–3).

Straight models of such economic central-place hinterlands show a decrease in demand density with increasing distance from the commercial centre. Close to markets, high demand density and transport efficiency enable continuous commercial activity (Plattner 1976). As the distance to the market increases, the zone of viable commerce is determined by a ratio between the periodic trader’s minimum daily income threshold and transport costs. Finally, a zone is defined, where demand falls below the trading threshold, and the transportation costs are so expensive, that even itinerant trade cannot be sustained. A model of key regions comprising the trading hinterland implies that the comparative pattern of consumption of individual communities is expected to vary regionally. Gateway communities or elite residences should demonstrate markedly different patterns of consumption and access to wealth markers than contemporary productive settlements. As part of this phenomenon, there should also be some evidence for cultural features associated with increasing specialisation, such as production, provisioning and distribution. Finally, institutional changes of the type suggested by Hodges, should also manifest themselves in increasing forms of centralised control.

Corridors of movement, settlement and exchange

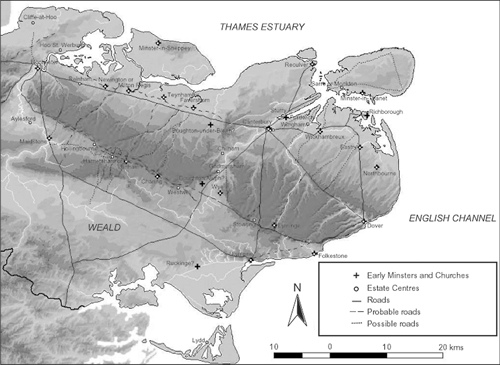

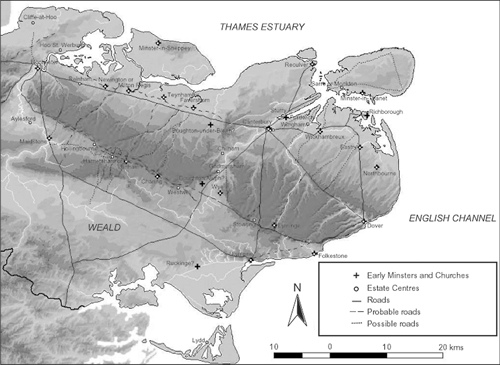

Although this economically deterministic model runs the risk of oversimplification, there is some evidence for such restricted commercialisation in Early to Middle Anglo-Saxon Kent. Reconstruction of the region’s Anglo-Saxon transport geography presents a useful framework to examine the siting of many of the important settlements of the period. Drastic geomorphological change to the landscape of East Kent, as a result of Holocene sea-level changes and local coastal responses, means that many of the settlements of interest are now up to several kilometres inland (Fig. 8.1). Of particular importance amongst these, are those around the former Wantsum Channel in north-east Kent which have been continually argued to represent comparable, though possibly earlier, specialised trading sites to those excavated in other parts of England. In addition to such evidence of past riverine and coastal movement, the network of Roman roads radiating out from the civitas capital of Canterbury, and some Iron Age and Prehistoric trackways, continue to be preserved in part as contemporary routeways (cf. Margary 1946 and 1948; Knox 1941). Finally, the evidence for Anglo-Saxon and Medieval detached pasture, in the form of -den place-names, High Medieval lists of extra-manorial demesne and other charter evidence, has prompted some authors to posit a number of possible ancient droves existing as trackways and sunken lanes linking the northern coast with the Weald in the south-west (for example Everitt 1986, 36 Map 1).

FIGURE 8.1. Map of East Kent, showing the reconstructed coastline c. 800 and its relation to some of the sites and roads mentioned in the text. The digital elevation model of East Kent was produced in ARCVIEW at 50m pixel resolution from 10m Ordnance Survey digital contours provided by the Digimap Project (http://edina.ac.uk/digimap/).

Spatial analysis in the form of Kolgomov-Smirnov testing of Early Anglo-Saxon cemetery distribution in East Kent suggests that these were significantly structured in relation to existing routes of communication, i.e. Roman roads, navigable rivers or the coast. Approximately 85 percent of cemeteries are seen to lie in highly visible locations within 1.2km of these routes, while the location of the remaining sites can be argued to correlate closely to predicted droves, linking thirteenth-century estate centres with their appurtenant Wealden pig-pasture. Although the antiquity of these latter routes is uncertain, the case argued by historians (e.g. Everitt 1986; Witney 1976), the number of denns mentioned in Anglo-Saxon charters from the mideighth century onwards (such as Sawyer 1968, Nos. 24–25, 30, 33, 37, 123 and 125), the correlation of these routes with computerised GIS ‘least-cost path models’, and places-names containing the element -ora (Brookes forthcoming), all suggest a clear tendency for sites to be located close to roads or routeways. Given the conspicuous use of above-ground markers in Kentish cemeteries (in the form of secondary interment in prehistoric barrows or Roman monuments, as well as primary burial in Anglo-Saxon barrow cemeteries or cemeteries with other visible grave structures – Shephard 1979; Hogarth 1973) and the close association of burial throughout the period with the prevalent routes of communication, a deliberate rite can be suggested, determined in the first instance by selection of places in the landscape visible from the patterns of movement of the living.

The evidence from the distribution of Early Anglo-Saxon cemeteries offers a picture of fossilised social movement from which to compare the pattern of hierarchical locales. In this regard, Tatton-Brown’s Kentish gazetteers of early towns (1984) and ten ‘old minsters’ (1988) finds close topographical correlation with both this pattern of Early Anglo-Saxon mortuary structures and Late Roman settlement. Utilising further documentary sources and the distribution of archaeological complexes, Everitt (1986) has also argued for a number of ‘seminal place’ estate-centres, forming the nucleus of colonising tenurial holdings in the North Downs and Weald. His hypothesis has stressed the importance of diverse economic conditions in the make-up of early estates by looking at the ancient patterns of land usage in terms of their detached lands and ancient common rights (f Witney 1976 and 1982; Everitt 1979 and 1986). Significant links between the more intensively cultivated lowland estates in the northern coastal fringe and Holmesdale valley and dependent appurtenances in the Weald and North Downs have been argued to reflect not merely the pattern of economic settlement, but also the underlying basis of later administrative structures. Thiessen Polygons constructed around these settlements confirm the contrasting economic zones of agrarian resources underlying their topographical shape, and the importance of their location, almost equidistant, along the routes of communication (Fig. 8.2).

If Everitt’s interpretation can be accepted (1986, 339–41), that a relatively established system of estates with its origins in the pattern of Romano-British settlement, formed the basis of seventh-century ecclesiastical foundations, the importance of network utility becomes clear both as a component of Middle Anglo-Saxon economic organisation and as a link to earlier patterns of ostentatious consumption. In the purely functional terms of an integrated regional system, nodal settlements could be predicted at the junction of major modal networks, where the costs of transference are minimised. As central-places for tenure spanning a variety of agrarian resources, and the further administrative implications such a pattern of estates suggests, manorial centres therefore needed to be sited at the nexus of inland routeways. Similarly, the link between trader mobility and periodic markets stresses spatial organisation circumscribed by geographical and social restrictions. The importance of Sarre, for example, has been seen with respect to its location at both the major Roman crossing point and at the conflux of the double tidal waters of the Wantsum Channel (Brookes 1998, 29–32). Fordwich’s significance has been stressed due to the settlement’s position at the tidal head of the Great Stour, and its probable role as the emporium for the nearby villa regalis at Sturry and Canterbury itself, while also offering the most likely point of trans-shipment between the sea-going Channel and coastal vessels, and the inland riverine modal network. Equally, Sandwich’s strategic position at the southern entrance of the Wantsum, adjacent both to the Roman roads to Dover and Canterbury and the large sheltered haven of the Meacesfleote, offered it topographical attributes which would secure its importance until well into the medieval period.

FIGURE 8.2. Thiessen polygon interpolation, showing the environmental pays of Kent and their relation to early estate-centres, as defined by Everitt (1986).

These general functional characteristics of settlement appear to be supported by inland settlement also, and the tentative case for a continuity of central-place functions from Romano-British territorial organisation seems unavoidable. Central to this interpretation of the settlement pattern of early Kent is a bridging argument, linking reoccurring observed phenomena rather than verified empirical data. An example of this line of argument is offered by the settlement of Eastry, though it could just as easily be Faversham, Milton Regis or Maidstone. Eastry appears as a Roman road-side settlement occupying the cross-roads of the Richborough-Dover road (Margary 100 or Stane Street) and a prehistoric trackway from Sandwich to Wootton (O’Grady 1979, 114). Roman finds are also known from the immediate environs (ibid., 113) and a Roman cemetery at Walton (Gibben 1902) indicates a level of pre-Saxon settlement. A number of Early AngloSaxon cemeteries and burials surrounding the village at Updown (‘Cemetery III’: Hawkes 1974; 1976; 1979), Buttsole (‘Cemetery I’: Meaney 1964, 113; Hawkes 1979), Eastry Mill (‘Cemetery IV’: Hawkes 1979) and at Eastry House (‘Cemetery II’: Hawkes 1979), are testimony to a substantial local population, often linked to an inferred AngloSaxon villa regalis. The latter suggestion relies on the validity of some Late Anglo-Saxon documentary evidence detailing seventh-century events having occurred at Eastry (Hasted 1799, iv, 216) and the association of the place-name with the modern settlement (cf. Arnold 1982b, 121). ‘Eastry’, documented as Eastorege in a ninth-century charter, has been interpreted as ‘the eastern district capital’ (Hawkes 1982, 75) and is taken to indicate both the existence of administrative sub-districts in Late Anglo-Saxon Kent and the importance of the settlement within the royal estate system. The latter argument has prompted the identification of Eastry Court Farm as a potential Anglo-Saxon administrative centre or royal residence (Hawkes 1979, 95) despite little archaeological justification (Arnold 1982b, 135; Parfitt 1999, 50) and suggested the association of Eastry with the unnamed twelfth-century great church listed in the Domesday Monachorum (Tatton-Brown 1988, 107). The correlation of Iron Age, Romano-British and Anglo-Saxon archaeological complexes, topographic suitability, place-name evidence, historical allusions and early ecclesiastical associations all indicate a form of ideological, if not necessarily physical, continuity.

The above example could be restated for a number of different settlements and it seems clear, certainly from the point of view of early ecclesiastical centres and villae regales, that an association with the Roman past was deliberately fostered. Roman precedents are known by Sturry (Rigold 1972; Brookes 1998); Faversham (Philp 1965, l11; Jessup 1970, 189; Detsicas 1983, 131–3; Everitt 1986, 109–12); Milton Regis (Kelly 1978, 267; Detsicas 1983, 81), Lyminge (Kelly 1962, 205; Detsicas 1983, 143–4), Wye (Detsicas 1983, 84, 97 etc.) and Wester Linton, near Maidstone (Detsicas 1983) among others. The influence residual Romano-British finds had on the siting of early churches is equally apparent as is demonstrated by the association of Roman buildings with churches at Lyminge (Detsicas 1983, 143–4), and the minster foundations at Reculver and Richborough for example (Gem 1995, 42; Bushe-Fox 1928, 34–40).

If the Romano-British settlement pattern prejudged the distribution of later economic centres, the routes of communication themselves constrained the flow of wealth through the kingdom. Certainly, restrictions on movement and exchange and the importance placed on negotiated places of social interaction are implicit in documentary sources. Evidence, particularly from palynology, stresses the importance routes of movement took in the construction of social space. Roads are seen as delimiting boundaries (e.g. Hooke 1985, 58), operating as hundredal meeting places (ibid., 102) and provide functional benefits to military and economic endeavours. Movement along the defined routes, on the other hand, must be seen with respect to contemporary social conditions. The Kentish law-codes of the seventh century offer some evidence of concerns for the movement of people and goods. The wording of the Laws of Æthelberht, and particularly those of Wihtred and of Ine of Wessex, stress the importance of roads for movement throughout the kingdoms, with heavy penalties being exacted for unannounced travel off the established routes of communication. Specific laws protecting travellers on roads from robbery, such as is evidenced by Æthelberht 19 and 89 on the other hand, suggest both the importance safe transit through the kingdom held for the king, and that highway crime was sufficiently common-place it required explicit measures for it to be suppressed.

Given the high number of laws dealing with foreigners, strangers and traders (e.g. Æthelberht 19; Hlothere and Eadric 15; Wihtred 4 and 28) it is conceivable that these measures indicate increasing levels of royal control placed on the movement of people and goods through the kingdom; an observation many commentators have associated with taxation (e.g. Carver 1993; Reynolds 1998a, 237). Certainly, other evidence suggests that systems of taxation were becoming more widespread during the mid seventh and eighth centuries (such as the Tribal Hidage: Davies and Vierck 1974, 136–41), but just how much the archaeological pattern of coin loss, for example, can be taken to represent top-down legislation or bottom-up decentralised trading, is debatable. Given the hypothesised economic constraints of the period, wherein goods of inelastic demand were traded in order to bear the costs of transport through sufficient profit, and the environment with little state provisioning of public goods and uncertain and dangerous transport patterns, it is suggested that it was in the interest of traders themselves to restrict alienable exchange to areas protected by law-codes and higher authorities, i.e. roads, fairs and markets.

Distributional patterns of consumption

The characterisation of the period in terms of increasingly exploitative relationships between dependent social classes, offers a further hypothesis by which to compare the differential distribution of commodities among communities accessing common distribution networks. Attempts at investigating mortuary evidence to explain economic concepts of accessibility and consumption of goods, and their use to express wealth (accumulation), social standing (differentiation) and cultural position (where possessions ‘flag’ certain cultural discourses) are well attested in archaeological practice. Recent distributional methods differ in their attempt to quantify the interment of commodities, with respect to units of economic consumption, such as individuals, households, or communities (Loveluck 1994 and 1996; Hirth 1998).

FIGURE 8.3. Trend surfaces produced from the average number of imported artefacts interred with each individual in Early Anglo-Saxon cemeteries of East Kent. The interp lated surfaces were produced in ARCVIEW on the basis of an inverse distance weighting (IDW) regression function from the twelve closest sampled points.

Trend surfaces derived from counts of foreign or local objects within cemeteries, and the percentage of the interred population with such goods, reinforce an impression of wealthy coastal communities, particularly along the Wantsum and Dover coasts (Fig. 8.3). Inland redistribution, by contrast, focuses mainly along the Dover-Canterbury road, also identified as a major routeway by the distribution of Early Anglo-Saxon cemeteries. To the south and west of the kingdom, a noticeable fall-off in the amount of both imported and locally proven-anced material further demonstrates the polarisation of wealth along the Thames estuary/Continental axis. An immediate impression gained from these regression models, is the stark contrast between imported artefact consumption prior to and after ad 600. Although the distribution pattern for both periods is roughly similar, with particular conspicuous consumption visible among the communities of the eastern and northern coasts (including a particular dense cluster in the Canterbury environs), the sharp decline after 600 in the deposition of imported goods suggests a changing role in the mobilisation of these objects. Sonia Hawkes (1970, 191; 1982, 72 and 76) has suggested that the later sixth century witnessed increasing royal control over foreign exchange contacts from the basis of inferred military components in the communities of Sarre and Dover. That these overtly military phases are followed by a period of decreased material consumption, despite evidence from documentary sources and coin finds to the contrary, suggests imposed change in the social role of objects.

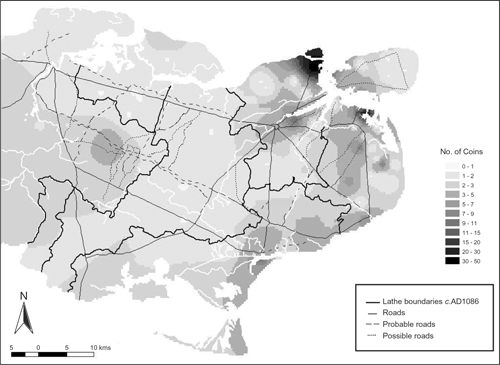

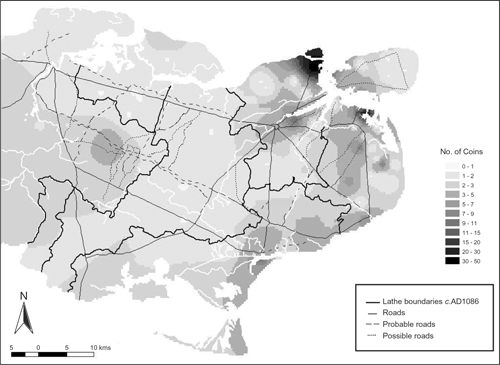

The pattern of supply and demand underlying the differential consumption of wealth during the sixth and seventh centuries, can be compared with the patterns of seventh-to ninth-century coin finds in East Kent (Fig. 8.4). The generally coastal distribution of areas of high coin loss fit well with the model of important coastal trading suggested by the distribution of imported goods and media of exchange such as weights and measures (<f Scull 1990) during the Early Anglo-Saxon period. Given issues of specialised alienable exchange, implicit in monetary transactions, this distribution pattern sits favourably with the idea of foreign trade and it is perhaps telling that the zone of monetary exchange extends further south along the coast than in previous periods, to include Lympne and the Romney Levels.

The lack of coin finds near the estate centres of the Swale and Holmesdale, by contrast, suggest an interpretation of differential regional access to the means of exchange. Despite the lack of clear Early Anglo-Saxon cemetery evidence from the Swale region from which to extrapolate a model of local consumption, the density of Anglo-Saxon estate centres in this region, and the clear pan-environmental structure of these settlements, suggests an economic basis operating primarily through non-monetary means. By contrast, the communities of the Dover and Wantsum coast and their immediate hinterland, such as Eastry and Northbourne/Great Mongeham and indeed Canterbury itself, can be recognised both to access foreign commodities from the sixth century, and as peaks of coin loss in the seventh. The coincidence of coin finds in this area with the pattern of earlier imported good deposition suggests that these regions probably engaged in limited price-making markets. The model of the highly fragmented nature of Middle Anglo-Saxon markets, meant that only communities with direct access to alienable trade could engage in monetary exchange.

FIGURE 8.4. Trend surface of Early Medieval coin finds in East Kent. Surface produced from coins c. 500-899 listed in the EMC up to 6 July 2001 in ARCVIEW at IDW12 regression.

That areas of particularly low coin loss can in some cases be equated with known important Late Anglo-Saxon estates, such as the regio and minster of Milton or the lathe of Wye discussed by Everitt and Jolliffe respectively (Everitt 1986, 302–32; Jolliffe 1933), raises the possibility that these areas can be identified as regions where exchange through the estate mechanism restricted active participation in price-making markets. In contrast to the monetary zone of alienable exchange identified along the eastern margin, the inland ‘productive’ site of Hollingbourne offers the only comparable example of such negotiated exchange in the west. The location of this settlement at the important cross-roads of routeways linking the historically discrete territories of East and West Kent, the denns between the settlements of the Swale and their Wealden appurtenances, and the environmental junction of the pays of Chart, Holmesdale, Downland and Weald, all single out its suitability for localised trading. Beyond favourable topographical criterion, Hollingbourne’s importance, as is probably the case with the ‘productive’ sites of Reculver and Richborough, may well be related to the ecclesiastical foundations of the seventh century. Church involvement in the resettlement of Richborough and Reculver have already been mentioned, and it is possible that Hollingbourne represents an ecclesiastical foundation, without substantial Early Anglo-Saxon precedent, as part of the original minsterland of Maidstone of which it is a named dependency in the Domesday Monachorum (Everitt 1986, 332).

A comparison between the regression models of Early Anglo-Saxon consumption and Middle Anglo-Saxon coinage demonstrates the importance of ‘new’ sites within the pattern of controlled exchange. Unlike communities close to the estate centres and coastal sites of the Early Anglo-Saxon period which demonstrate both high numbers of imported goods and Middle Anglo-Saxon coin losses, those of Rich-borough, Reculver and Hollingbourne are unremarkable in their consumption of wealth during the earlier period. By contrast, the almost unparalleled number of sceatta and tremissis finds at the two coastal sites (Rigold and Metcalf 1984, 258–60) and the clear peak of coin loss at Hollingbourne, may well be indicative of large-scale monetary exchange on a scale only achievable by, and under the protection of, institutions such as the Church.

Conclusions

The Middle Anglo-Saxon economic development of the kingdom of East Kent, of which ‘productive’ sites are only one phenomenon, can be related both to the topographical attributes of the region and local issues of consumption and exchange. A comparison between Early Anglo-Saxon centres of wealth consumption and the distribution of Middle Anglo-Saxon coin finds in East Kent presents clear implications for the interpretation of developing settlement hierarchies. Important similarities in the geographical structure of Early Anglo-Saxon consumption and later manorial organisation stress, not least, the importance corridors of communication took in structuring the social and economic landscape. Significantly, these same roads and routeways are seen as central to the structure of Early Anglo-Saxon mortuary structures.

That the pattern of Middle Anglo-Saxon estate centres finds close correlation with these same places, suggests at the least a continuity of integrated regional production from the earliest phases of settlement. As one of the criteria governing wealth circulation, access to focal points within the spatial network of routes, can also be argued to underlie differential patterns of consumption within these interred communities. The fall-off curves in imported good deposition within Early Anglo-Saxon cemeteries indicate the importance of specific coastal settlements for the redistribution of these objects, as has been suggested by other lines of historical and archaeological enquiry, and may well provide evidence of so-called ‘gateway communities’ discussed in geographical anthropology. Of importance, nevertheless, is the recognition of substantial change in the mobilisation of these resources after 600, with particular foci of consumption being suggested at known Middle Anglo-Saxon estate centres during the later seventh century. In support of these patterns of exchange, trend surfaces of seventh to ninth-century coin finds indicate the importance of coastal location for active engagement in alienable exchange. In addition, areas of few coin finds and certain sites of unusually high coin-loss possibly reflect local responses to the framework of large-scale institutional exchange and associated restrictions.

* Recent excavations in the immediate vicinity of this burial suggests that this may actually be an isolated burial (Parfitt 1999, 52).