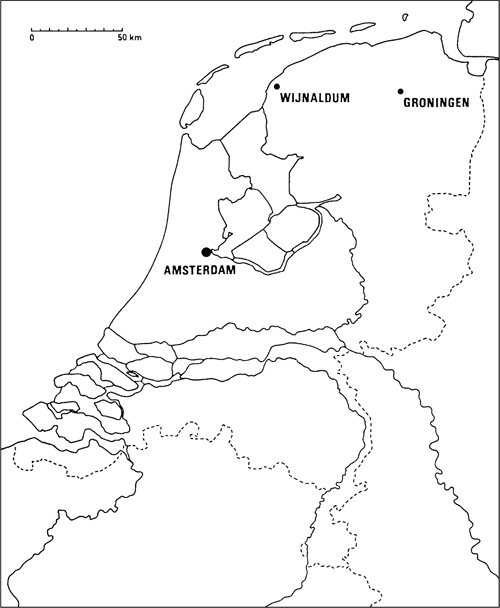

FIGURE 17.1. The location of Tjitsma terp, Wijnaldum (after Besteman, Bos and Heidinga 1993).

Tjitsma is a terp or dwelling mound near the village of Wijnaldum in the coastal area of Friesland province, in the north-west of the Netherlands (Fig. 17.1). It is one of several terpen still visible in the landscape which, in the provinces of Friesland and Groningen, are frequently searched by metal-detectorists and which yield a lot of metal finds.

Between 1991 and 1993 part of Tjitsma terp was excavated, for four principal reasons. First, an increasing number of metal-detector finds indicated that the top of the terp was eroding. Secondly, excavation allowed the erosion caused by agricultural activities like ploughing and deep-ploughing to be studied and raised the prospect of yielding more information on how to improve the protection of this type of monument. Third, in the 1950s a large gold and garnet brooch had been found (front cover), which suggested that Tjitsma represented the remains of an Early Medieval trading place of some importance. Finally, excavation offered the opportunity to establish an improved regional pottery chronology for the Early Middle Ages and to learn more about the terp region in general.

The excavation was undertaken by students and staff from the Universities of Groningen and Amsterdam. The number of excavated levels varied in each trench, a mechanical digger removing soil in layers of five centimetres or less, so that all the metal finds could be located by use of a metal-detector and plotted three-dimensionally. Additionally, the soil from features was wet-sieved through a 4 X 4mm mesh. As a result, the excavation yielded many small finds like beads, and environmental evidence such as charcoal and small fish and bird bones. Several different occupation periods were defined by pottery finds and in post-excavation eight different phases have been identified (all AD): I, 175-250; II, 250–300/325; III, 425–550; IV, 550–650; V, 650–750; VI, 750–800; VII, 800–850; VIII, 850–950 (Gerrets and de Koning 1999). There was a small gap in occupation between 325–425.

FIGURE 17.1. The location of Tjitsma terp, Wijnaldum (after Besteman, Bos and Heidinga 1993).

Craftworking evidence was found, for instance half-manufactured combs and unworked blanks are evidence for bone-and antlerworking, although the small scale of production suggests the items were for local consumption instead of wider trade. Textile production is indicated by the finds of pottery loomweights, bone needles and spindle-whorls of different materials inside some small buildings. Amber had been worked on site in the fifth and sixth centuries while melted glass paste and many beads indicate local glass production (especially of beads) in the sixth century (Sablerolles 1999). None of these crafts provide evidence for mass production. There is, however, much evidence for the working of various metals, which seems to have taken place on a somewhat larger scale.

No evidence was found for the refining of gold and silver at Tjitsma, but there were traces of both the melting and working of precious metals in different periods of occupation. Evidence for the working of gold and silver was relatively common, the finds dating from the beginning of the fifth century through to the ninth century and including droplets of gold and silver, ingots, bars and rods, a die, a small hammer and a crucible fragment with tiny gold droplets. Other evidence is more indirect, coming from fragments of silver and gold objects, gold wire and touchstones.

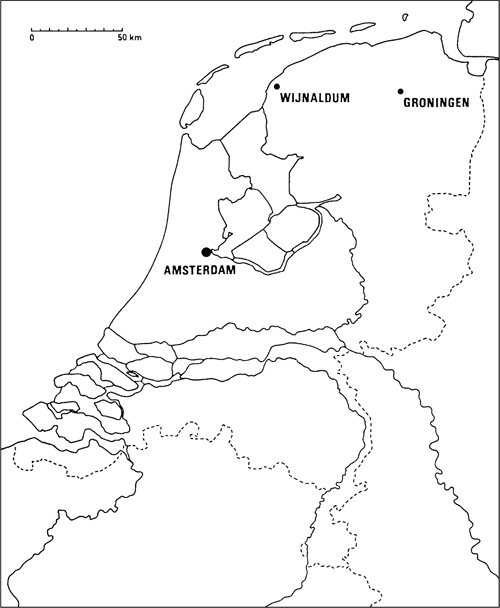

The oldest indications of silverworking on the site came from the fifth century, from an ingot, a bar, a rod, and a droplet. A small iron hammer (Fig. 17.2a), of a type usually interpreted as used for working precious metals, was also found. Although no direct evidence for goldworking was found from this period, a gold sword mount containing eight gold nails was found with some pieces of lead, which was clearly meant for remelting or reuse (Fig. 17.2b).

Possible evidence for continued metalworking in the next phase of the site (IV, or 550—650) was provided by a touchstone with traces of gold (Fig. 17.2c). These stones, used to test the quality of metals by the marks they leave on them, provide only indirect evidence for goldworking because they were also used in trade. This particular touchstone is rectangular, black (like lydite) with flat sides and slightly rounded edges and corners, its very regular and smooth surface having traces of gold on the front as well as on the back. The same period also yielded a fragment of rough garnet, retrieved from a well. Garnet, a semi-precious stone, was much used in the Early Medieval period in precious gold jewellery like the large golden cloisonné disc-on-bow brooch found at Tjitsma (front cover) (Mazo Karras 1985, 168—71; Nijboer and van Reekum 1999).

FIGURE 17.2. Finds associated with precious metalworking. (a) Small hammer. (b) Gold ?scabbard mount with nails. (c) and (d) Touchstones (all J de Koning). Scale 1:1.

More finds date from 650—750, for example a crucible rim sherd fragment with a greyish-green glaze on the outside and also on the inside near the rim. The glaze contains many gold droplets, which vary from 0.1—0.5mm in diameter. A more spectacular find is a die for making cross-hatched patterns on gold foil (Fig. 17.3). Crosshatched foil was commonly used in cloisonné jewellery of the period, being mounted in cells behind plates of translucent garnet. The Tjitsma pattern consists of squares of about one square millimetre, each divided into sixteen or twenty smaller squares. The die itself is of about thirty square millimetres, is made from copper-alloy (Tulp and Meeks 2000), and was found near to the brooch fragments and other traces of goldworking. No evidence for silverworking was found in this period.

FIGURE 17.3. Copper-alloy die stamp with cross-hatched decoration. Size of object 17.4 × 16.1mm. (Photograph: Colin Slack, English Heritage)

Another touchstone was found in layers dating from the next period (750—800), again of oblong shape with flat sides and slightly rounded edges, and bearing traces of gold on one side (Fig. i7.2d). From the end of this period or the beginning of the next derives a thin gold rod which under the microscope shows stress marks caused by hammering. From Period VIII (850—950) one gold and two silver droplets were found which means that this is the only period in which it is certain that there was contemporaneous silver as well as goldworking.

Some other precious metal finds were found both before and after the excavation by amateur archaeologists, including a thick golden rod, a silver and a gold bar, a silver drop, a piece of melted silver and two gold melt pieces. These, and the finds from the excavation, are not concentrated in one specific part of the terp, with the exception of those from 650—750 which were found in the eastern part of the excavation. In the final period the finds seem to be from the southern area. Gold or silver working evidence does not occur in every occupation period but this does not necessarily mean that precious metals were not being worked; simply, excavation has not provided any positive evidence for the practice. The caveat must be added that not all the finds can be dated and this may have influenced the overall picture of precious metalworking.

It seems likely that at least in those periods for which there is evidence of gold or silver working, an itinerant smith went to the terp for commissions, because there is no direct evidence for a precious metalworker living at Tjitsma. What is clear from the above-average number of finds of precious metalworking, like bars, ingots and rods, is that between the fifth and ninth centuries there were times when there was much gold or silver in circulation.

Not only were many iron objects found at Tjitsma, there was much evidence for ironworking, including slags, fragments of hearth lining, hammerscale and bars. Two kinds of iron ore exist in the Netherlands: iron ore from rattlestones, which are found at the Veluwe, Nijmegen and Montferland; and bog ore found in the north of the Netherlands in peaty areas. At Tjitsma however, no traces were found of the production of iron from either bog ore or rattlestones. Instead, bars were probably imported from the south of Sweden.

Some early iron slags date from the period 250–300 and a feature was found which could be interpreted as the floor of a smithy, containing many corroded iron objects. The floor surface consisted of a rusty coloured loamy layer that contained a lot of charcoal and hammerscale. Unfortunately, the objects within were too corroded to distinguish between scrap metal, parts of objects, semi-manufactured objects or even tools.

By Period III (425–550), the concentration of ironworking finds had moved from the north to the west of the terp and a small amount of slags were also found dating to 475–550. From the beginning of the sixth century the evidence for ironworking began to increase. From Period IV (550–650) there is a large concentration of slags, hearth linings and bases. Because the slags formed on the bottom of a hearth, the form of the hearth itself can be deduced. All those from Tjitsma are more or less round and plano-convex in shape, the majority of which are datable belonging to the period 550–650. In many cases cinder was also found in relation to metalworking finds like hearth material or slags.

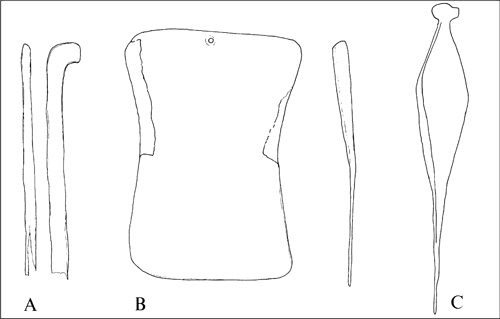

After 650 the number of ironworking finds diminishes quickly, but this picture is tempered by many of the iron finds and bars dating from this period. Most probably, ironworking continued elsewhere, perhaps to the south of the site which was not excavated. Different types of iron bar seem to have circulated during the eighth and ninth centuries, and can be divided into four groups. The first type, represented by two bars, is long, thin and flat (Fig. 17.4a) while another group are ‘ploughshare’ bars; Tjitsma has two which are quite flat with partially folded sides (Fig. 17.4b). The third type, identified by Schmutzhart (1997, ii, 64), is a spindle-shaped bar with a knob on one side and a long sharp point on the other (Fig. 17.4c). The fourth group consists of iron rods, but it is unclear whether these objects are bars, semi-manufactured objects or smithing refuse. Among the tools used in manufacturing iron objects were two large iron punches of long, rectangular shape, tapering at one end. Only one can be dated, to 775–850 (ibid., ii, 73).

FIGURE 17.4. Iron bars from Tjitsma.(a) Long bar. (b) ‘Ploughshare’ (after J de Koning). (c) ‘Spindle-shape’. Scale 1:2.

A total of 37.6kg of slag was found at Tjitsma, most of it from the western part of the excavation. The slag all derived from wells and middens rather than a smithy or workshop area and it is possible that the work area of the smith was situated slightly further to the west of the concentration.

During the excavation much copper-alloy was found, in the form of objects including coins, ingots, bars and sheeting, as well as scrap metal, drops, melt and casting pieces. Many of the sheet fragments are folded and some have clear cutting marks. Evidence for bronzeworking comes from lead fragments, which could have been used for alloying, found in the same contexts as pieces of copper-alloy and the fragments of crucibles, often from the same scrap metal contexts. Further evidence consists of moulds and several semi-manufactured objects.

From 250–350 bronzeworking was concentrated in the northern part of the excavated area. Four hearths were excavated, and open moulds for casting ingots, crucible fragments, copper and lead scrap metal, a copper ingot and three bars were all found in the vicinity. The smithy floor also dates from this period, hammerscale, iron objects, copperalloy and lead all being found in the floor, indicating these different metals to have been worked in the same place. Unfortunately, it is unknown whether one smith was working both metals, or whether different metalworkers were working alongside each other. It is also unclear whether there is a difference in the dates, with a smith working iron and later the same area being used by another smith, for bronzeworking, yet all within the same archaeological period.

In Period III (425–550) the focus of the bronzeworking appears to have shifted from the north to the west of the terp. No actual workshop was found, but all the metalworking finds were concentrated here, including two bars and several hearths. Many Roman bronze coins, both cut and uncut were also found in dated features, while to the east of the terp a coin was found together with a melted copper-alloy fragment; four other coins within a metalworking context were located near each other, some cut into quarters. Only four of the metalworking crucibles from Tjitsma contain copper-alloy droplets. All the fragments of crucible walling (except for two almost complete examples) are small, making it difficult to say anything about their original size or shape, but most date from the fifth to the beginning of the seventh century and appeared in the metalworking concentration, often in the same features as lead, copper-alloy, or moulds. Within this, the bulk of the copper-alloy finds recovered date from 550–650 and were concentrated to the west of Tjitsma. After 650 the number of bronzeworking finds diminishes rapidly with no concentration, although the stray finds tend to be from the eastern part of the terp and by Periods VI–VII (750–850) some copper-alloy finds were found in the south part of the terp but again no longer forming any concentrations.

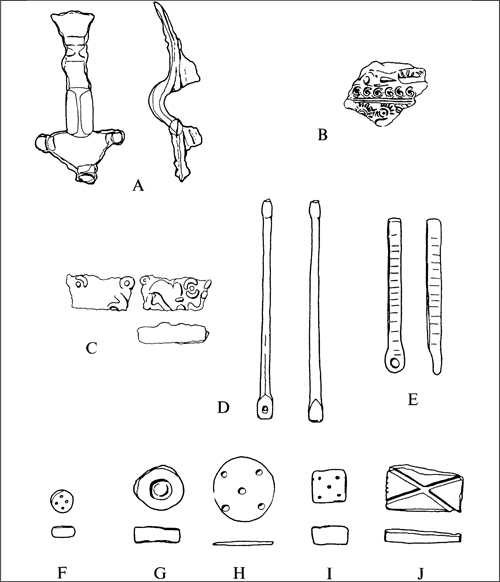

FIGURE 17.5. (opposite). Assorted finds from Tjitsma. (a) Unfinished copper-alloy cruciformbrooch. (b) Fragment of a mould for a brooch, probably of square-headed form. (c) Lead object with an animal, possibly a model for mould-making. (d) and (e) Copper-alloy balance arms. (f )-–(j) Copper-alloy weights (all J de Koning). Scale: all at 1:1.

Among the metalworking debris was much hearth material, weighing 21.8kg and characterised by being mostly glazed on the inside, often with some slag remains attached. The hearth walls sometimes consisted of a more or less powdery, thick loamy layer in several colours, varying from yellow to pink/purple. No real tuyères (which protect the bellows from the fire) were found at the terp, only holes in the linings of hearths, through which the tuyères passed. These pieces of hearth lining had a very glazed and slag-like front, the earliest dating from 475–550 and the latest to 750–850. The tuyères were all found in contexts containing iron slags and fragments of hearth material.

Three semi-manufactured copper-alloy objects of interest were also found in the metalworking areas. The first is a cruciform brooch with its casting flash lines still visible and the perforations for the hinge yet to be made (Fig. 17.5a). The other two are semi-manufactured keys. One was found together with two fragments of lead sheet and while neither keys have flash lines, they remain rough and unfinished, with their bits yet to be added. Production is also indicated by open moulds, some dated to the sixth century, which were found principally in the metalwork concentration. They include the fragment of a mould for a brooch which could have been part of either a closed mould or one consisting of several parts. The brooch was probably of squareheaded form and the mould preserves much fine detail (Fig. 17.5b).

Much lead was found in the excavations, probably having been used in bronzeworking; almost without exception, pieces of lead were found together with copper-alloy scraps and sometimes with pieces of moulds or crucible sherds.

The first period of the site’s use revealed lead finds only in the smithy floor and near some hearths in the northern part of the terp, but from the end of the following period (425–550) onwards, more lead finds were found across the site. Noteworthy among these is one object decorated on both sides (Fig. 17.5c). The find looks like an animal figure but is unlikely to be a trial casting because it has no flash lines and the fact that both sides are decorated make it doubtful that it is a brooch or a brooch trial piece. It may instead have been a model used for making a two-piece mould.

There are a number of finds that cannot be associated with only metalworking. For instance, several weights and scales have been recovered at Tjitsma, as have two fragments of copper-alloy beam balances, all of which may have been used in trade. One balance fragment is long and rectangular with a hole at one end, while the other has the same shape, but is shorter, having lines upon it, presumably for measurement although they are not equally spaced (Fig. i7.5d and e). Among the many weights from the terp, a selection of which are shown in Fig. i7.5f-j, most were retrieved from the area of metalworking although not apparently deriving from these manufacturing contexts. All the copper-alloy weights are flat and have marks, for instance four or five dots or a cross, but there seems to be no relation between the weight and the marks. Most appear to date from the seventh century and help to suggest a date for the balances.

More immediately appealing is the large golden cloisonné disc-on-bow brooch found at Tjitsma in the 1950s (front cover). Although it is known to have been found in a ditch, the exact findspot is unclear. Over the years other fragments of the brooch have been discovered by metal-detectorists and during the excavation several more fragments were retrieved. The brooch dates from the late sixth to early seventh century and consists of pieces of silver and gold alloys (Nijboer and van Reekum 1999). Its back has evidence for cutting, suggesting two possible interpretations: that it was in the possession of a smith for reuse, or for repair. Of these, the cut-marks and the absence of any fragments of the disc suggests the imminent reuse of the brooch. In this scenario, the disc could have been reused for making another piece of jewellery. Evidence supporting its need for repair could be the wear evident on the brooch (Nijboer and van Reekum 1999). The pattern of the foil die found in excavation on the terp (Fig. i7.3) does not fit that on the gold foil of this brooch, making it uncertain whether the brooch was produced locally. The die and the rough piece of garnet are, however, evidence that a smith working at Tjitsma had the knowledge to make these kind of brooches.

Among other precious finds from the site was the gold scabbard mount, dating from the early sixth century, excavated in a layer of turves (Fig. 17.2b). Only one side is decorated, with rows of small circles consisting of granules carelessly melted together, the rows separated from each other by thin, uneven, strips of gold wire. The edges of the mount are bordered by a row of granules and the corners are pierced with small holes. The object had been folded double and then used to contain eight small gold nails which would fit through the mount’s holes – the nails therefore appear to be associated with the mount, especially had the mount been one of a matching pair, positioned either side of a scabbard. When taken off, the eight nails had evidently been kept in one of the mounts. It is uncertain whether the mount and the nails were going to be reused on another scabbard or whether they were all intended for remelting.

Among other gold or gilded objects were a pendant, a bird brooch, the decorated knob of a brooch and a pendant using a forged coin. Few silver objects were found and where datable, belong to the eighth and ninth centuries. The objects consist of two brooches, an Arab dirhem, a pendant and two bracelets. A silver nail which was recovered may have been used to attach a shield boss (Huisman 1997).

Among the many copper-alloy objects recovered are mounts, buckles, brooches, needles, jewellery, weights, keys, knives, nails, tweezers and military objects (Huisman 1997). The lead and lead/tin alloyed objects appear to date from around the eighth and ninth centuries and include three mounts, a lead sieve, a weight, four spindle whorls, a pendant, a pseudo-coin fibula and a Maltese cross-shaped fibula (Huisman 1997). 145 iron objects were studied out of a total of about 2,500. Of these i45, about half were tools for working metal, wood, bone and antler, and possibly leather. The rest of the objects were used in hunting, personal grooming, and in a domestic context. No tools for agriculture or cattle were found (Schmutzhart 1997).

The problem with interpreting the results of the excavation is the representativity of the site. Tjitsma is only one in a row of terpen and remains only partially excavated, making it difficult to say something about social and economic differentiation between these settlements. Indeed, few examples have been excavated in the terp region more generally. In Oosterbeintum an Early Medieval cemetery was excavated in 1987 (Knol et al. 1995–6), while Ezinge and Godlinze were excavated at the beginning of the twentieth century (Waterbolk 1991; van Giffen 1919). In 1997 the lower levels of the partly-disturbed terp of Winsum in Friesland were excavated, but the finds remain only partly published in a small Dutch university publication. It is, consequently, difficult to compare Wijnaldum to other sites in the region. More recently, there have been many metal objects recovered from the terpen, but as metal-detector finds, they have no context. A familiar associated problem is the uncertainty over how many finds are being made but left unreported to the provincial archaeological authorities and museums. Such a loss of information is not new: in the first half of the last century much of the fertile soil of the terpen was sold and moved, destroying the sites in the process. Finally, there is an unevenness in the quality of research into these Early Medieval sites. In contrast to earlier excavations, wet sieving was undertaken during the Wijnaldum excavation, resulting, for instance, in the discovery of many beads and small bird and fish bone fragments. This level of information cannot be compared easily with the results from other sites.

With these reservations in mind, some comment may be offered. The importation of both metal, such as iron ore, and pottery at Tjitsma indicates the site’s participation in wider trade networks, despite the evidence for only small-scale craft production within the terp. Its location may have much to do with this. Tjitsma is located close to the sea, and to the important trade routes from Dorestad to England, north Germany and Scandinavia, and to the river systems heading inland. Interestingly, despite this, Wijnaldum appears never to have grown into a major trade centre. Within the wider context of the terpen, the discovery of metal objects appear to say something about the importance of some sites despite a lack of excavation.

Many gold finds are known from sixth-and seventh-century Friesland and among the metal-detector finds from terpen, some appear to be richer in finds than others. For example, Dongjum terp is quite rich, while a large gold deposit was found in Wiewerd. Wijnaldum similarly appears to be among the richer terpen, although not on the same scale as Scandinavian production centres like Birke or Helgo. Nevertheless, its imported goods and rich metalwork assemblage indicates that it constituted a small production centre engaged in trade and presumably controlled by a local chief. The principal difficulty remains the need for qualitative data from other terpen with which to compare Wijnaldum – and this provides the challenge for future archaeological investigation.

I would like to thank the following people and institutions: the Laboratory of Conservation and Material Sciences of the Groningen Institute of Archaeology (GIA), University of Groningen (RUG); Jurjen Bos and Danny Gerrets for their cooperation; Justine Bayley and Nigel Meeks for helping me with the analyses of several finds; English Heritage Ancient Monuments Laboratory and the Department of Scientific Research of the British Museum for the use of their facilities; and the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) for funding my internship at English Heritage.