Getting Started with Your Food Storage Plan

Five Things You Can Do Now

- Decide which type of food storage plan will fit your needs—Everyday, Basic, or Advanced.

- Use a food storage calculator. Evaluate the results.

- Make a list of the foods you already use that are suitable for storing.

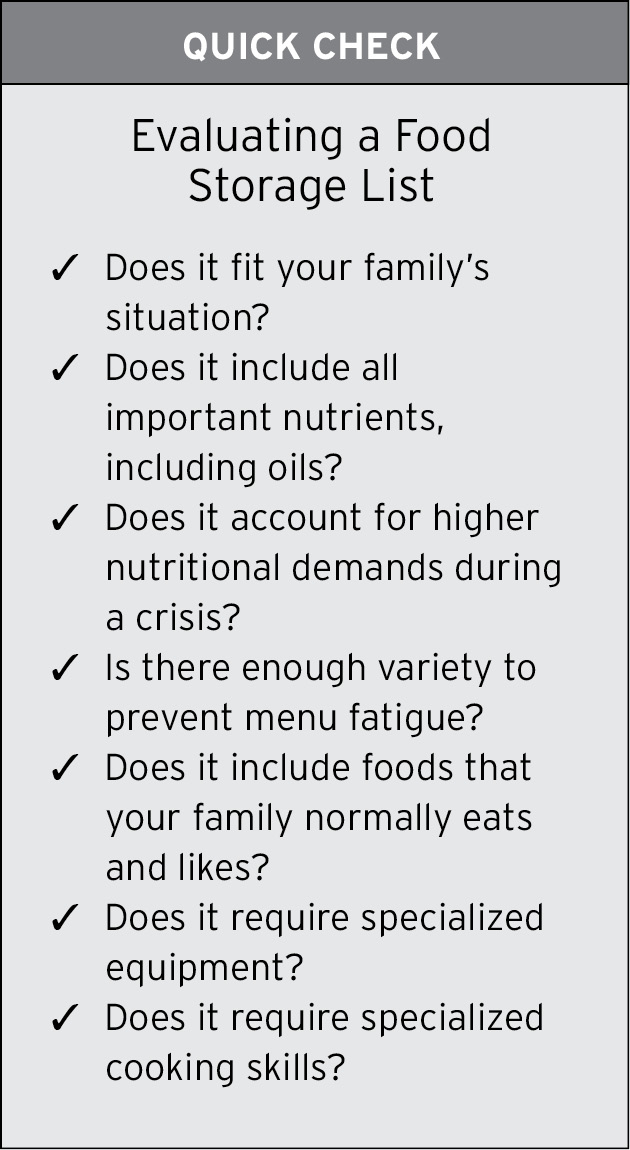

- Use the Quick Check to evaluate your existing food storage.

- Decide on one food you know you want to have in your storage and purchase enough of it for one month.

If you have not already done so, consider how comprehensive you want your food storage plan to be. What are your perceived needs? In other words, what are you storing food for? What level of commitment can you dedicate to preparedness and food stockpiling? Would you like to have backup food storage but do not have a lot of extra resources? Is acquiring a reserve supply of food something you can work at over time? This chapter will help you decide what level of preparedness will fit your needs.

Three Levels of Food Storage Preparedness

How and why you prepare is very personal. It’s helpful to think about preparedness in three levels, or stages. If your concern is about temporary disruptions or possible short-lived personal challenges, and if you want your meal plans to include foods you already use, you might select the Everyday Level of preparedness.

If you are interested in having up to a year’s supply of simple, basic foods, take a look at the Basic Level. If you feel an urgency to be fully prepared to the extent possible for any major natural disaster or breakdown of society and are strongly committed, consider the Advanced Level.

Everyday Level

The Everyday Level of food storage preparation focuses on short-term needs. It is balanced between foods you use daily and a few basic foods you store and continually replenish. It includes fruits, vegetables, eggs, dairy products, and meats and may include basic foods, like beans and grains. Use the food storage plans in chapter 15 to help achieve this level of preparedness.

Basic Level

The Basic Level focuses on essential storage foods and is minimal but adequate. This is a good place to begin if you want to keep it simple or if budget is a concern. It can be done inexpensively by purchasing foods in bulk and preparing them for storage yourself. The 7-Plus Basic Plan described in chapter 16 is a Basic Level plan. It can be combined with the Everyday Level and upgraded as your resources allow.

Advanced Level

The Advanced Level of preparedness starts with intensive stockpiling. Besides basic foods, it includes storing canned and freeze-dried meats, along with canned, dehydrated, or freeze-dried fruits and vegetables to approximate fresh food. Chapter 17 gives you detailed support for this level of preparedness.

You sustain this level of preparedness by supplementing stored foods with lifestyle modifications and self-reliance skills. This can include growing and preparing much of your own food, the cost depending on the lifestyle changes you adopt. Your overall living costs may actually decrease. Later chapters will discuss the attitudes, skills, and equipment necessary for making lifestyle changes.

Chapters 15, 16, and 17 will teach you how to create a comprehensive food storage plan, show you how to customize that plan, and give you the flexibility to meet your individual requirements.

Personally Speaking

My ideal plan includes all three levels of food storage and takes place in phases. To begin with, we stockpile foods we normally eat. This food is in my pantry and freezer. It is convenient to use and will see my family through about three months. It means I am not panicking if there is a local or regional disruption and that I can usually figure out something to fix for dinner without running to the store or relying on a box of mac and cheese.

I look at the second phase as food insurance. This is where we add to our three months of regular food and begin gathering basic foods that will keep us alive in the event of a long-lasting crisis. Certain foods, like whole grains, beans, sugar, and powdered milk, last a long time if stored properly. I keep them in the storage room in my basement. During this phase, it is important to acquire specialized cooking equipment and develop the skills to use these foods.

It is not realistic for most of us to store a whole year’s worth of the kinds of foods we eat daily. The drive-through at fast-food restaurants and pizza delivery are hard to duplicate. And it is just as challenging to reproduce the garden-fresh produce and fresh eggs, meat, and cheese we enjoy in our normal diet. Yet in a lengthy crisis, we want to be able to take care of our families. That’s where phase three comes in. I like it because it helps me plan to match, as close as possible, the kinds of foods we normally eat. It includes the basic foods we stored in phase two, plus things like fruits, vegetables, and meats. We also grow a garden and fruit trees to add fresh foods. This phase requires a total preparedness mindset along with accompanying skills and lifestyle changes. Though it takes time and considerable effort to achieve this level of preparedness, to the degree we can accomplish this phase, we will enjoy a feeling of self-reliance and peace of mind.

A Personalized Plan

Because no two individuals or families are identical and situations vary considerably, the best plan is the one that fits your unique goals, needs, and circumstances. There are no set rules and no easy, one-size-fits-all method. You will want your plan to be adequate, balanced, and consist of foods your family enjoys. Use worksheet 10.1 to help you evaluate your food storage plan. The worksheet is also found as a downloadable PDF on our website, CrisisPreparedness.com.

Planning from a List

A list generated by someone else will not likely fit your specific needs.

Many preparedness experts will provide lists of essential food items to store. These lists usually consist of basic, economical foods well-suited to long-term storage. They can be a good starting place and may sometimes be improved upon with only minor changes or additions.

Although it is tempting to simply choose a list and be done with it, someone else’s list of specific items is not likely to fit your family’s needs exactly, plus it can be confusing to even choose a list. Recommended items are often inconsistent from one expert to the next, and the suggested amounts of the same items often vary.

Food Storage Calculators

If you’ve explored food storage options, you’ve come across preparedness sites with food storage calculators that require you to enter the number of people you plan to feed and the number of months you want the food to last. These calculators then determine the amounts of specific foods you’ll need.

A basic list of generic storage foods is built into the calculator. The types and amounts are based on the expertise and opinions of the calculators’ creators. Using a basic list, the calculator multiplies the number of people by the number of pounds of each specific food per person. Some break it down by age to compensate for different caloric needs, but the results are only as reliable as the assumptions and the lists of foods programmed into them. Using a calculator has the same shortcomings as using a list.

Another kind of calculator is found on commercial food storage sites that sell dehydrated meal packages. These calculators are designed to sell their products and are not very useful unless you intend to purchase all your food from that company, which is not recommended.

7-Plus Basic Plan Food Storage Calculator

We have designed a calculator based on the 7-Plus Basic Plan, which takes into account all the variables discussed in the 7-Plus Basic Plan section of chapter 12. It is available on our website, CrisisPreparedness.com.

Other Considerations

Table 10.1 gives you some additional things to consider as you create your food storage plan.

How and Where to Buy Food Storage

Acquire Preparedness Items Systematically

Table 10.1

|

|

|

Plan for extra people. |

Sharing with relatives and friends, unforeseen guests, a longer-than-expected crisis, or for barter |

|

Plan for two years in the future. |

Needs change over time. |

|

Review and reevaluate at least yearly. |

Harvest time might be the best time because of abundant supplies of food. |

|

Plan for unique needs. |

Infants, young children, Those with allergies or chronic health problems |

|

©Patricia Spigarelli-Aston |

|

There’s no need to buy items quickly or all at once. Simply add small amounts of foods to your stockpile on a regular basis. Use worksheet 4.4 , “Master Shopping List,” to organize your purchases. You may want to acquire a month’s supply of each item before increasing the amount of any one item, or you may purchase items when they are on sale. Use shelf life to determine desired rotation and a replacement schedule. Shelf life is discussed in chapter 11.

Shop for Quality and Economy

Because you’ll seldom find a single source offering a complete selection of the highest quality items at the best prices, it pays to purchase from a variety of sources. Depending on where you live, you may be able to find local sources for food storage. Check with bakers, millers, grain brokers, feed dealers, and grocery wholesalers. Though you may have to repackage them for storage, purchase institutional sizes of dehydrated and other foods at restaurant supply stores, warehouse clubs, and similar outlets. Do not hesitate to ask for quantity pricing. Often, the most economical time to buy food is at harvest, when supply is at its peak. Be aware that closeouts may be offering last year’s goods, so check expiration dates.

Online Purchasing

Many preparedness companies do much of their business selling online. They sell dehydrated and freeze-dried foods in cans and in Mylar bags inside buckets. They also sell grains and beans in cans, poly buckets, Mylar bags, and in bulk quantities by the bag. Do not overlook shipping costs, which can substantially increase the total price.

Purchasing through a Co-Op

One way to minimize shipping costs is to join or start a co-op and buy foods with others by the pallet or truckload. You might also consider becoming a dealer or distributor so you can save 20 percent to 50 percent off normal prices.

A Worksheet to Help You

Use worksheet 10.1 to help you evaluate your food storage plan. For a downloadable PDF file, go to CrisisPreparedness.com.

©Patricia Spigarelli-Aston. For a downloadable PDF file go to CrisisPreparedness.com