1

CHINLE TIMES

When you come to the Petrified Forest-well, one guess may be as good as another! The greatest geologists, the greatest botanists, have bumped their inconclusive heads against it in vain.... It is the prime mystery in geology-the hardest nut, and the hardest wood, in the world.

Charles F. Lummis, southwestern writer, 1912

A few scientists and topographical engineers passed through the petrified forests in northeastern Arizona in the late 1850s, but their visits typically were brief and their examinations of the terrain cursory. From time to time, specimens of petrified wood were dispatched to schools and museums on the East Coast and in the Midwest, but no thorough scientific survey of the region occurred until the end of the nineteenth century, when the United States Geological Survey examined the region known as Chalcedony Park as a possible site for a national park. Local residents had given that title to the extensive deposits of petrified wood in the vicinity of the agate bridge. The mystical stone of the Greeks, chalcedony is a translucent milky or grayish quartz distinguished by slender fibers of microscopic crystals arranged in thin parallel bands. Chalcedony Park was never precisely defined and today is included in a section of Petrified Forest called Crystal Forest.

During the following decades both amateur and professional scientists explored the area's colorful badlands terrain. Most of them, like the naturalist John Muir, came at their own expense. But federal funding supported research by scientists from the Geological Survey and the National Museum. Such institutions as the Museum of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff, the Laboratory of Anthropology at Santa Fe, and the Museum of Paleontology at the University of California underwrote additional research at Petrified Forest. With the expansion of graduate education at the end of World War II, scientists could rely on the assistance of growing numbers of well-trained students. Throughout much of the American West, estimable scholars led their young charges to isolated sites in search of potsherds and other artifacts of prehistoric cultures or of the fossil remains of ancient creatures that had once inhabited the area. For graduate students, this fieldwork might amount to no more than an exercise in manual labor under the watchful eye of a renowned authority. But, at best, such excavations could result in the inclusion of the budding scholar's name among the coauthors of a brief scholarly article-the publications characteristic of contemporary refereed journals.

For Bryan Small, a graduate student at Texas Tech University. fieldwork at Petrified Forest National Park in August of 1984 culminated in a once-in-a-lifetime discovery. Small was working with a group ofpaleontologists from the University of California and other institutions that summer, examining the terrain near Chinde Point in the Painted Desert for plant fossils. In a small valley he came across an ankle bone, recognizably that of a dinosaur, which summer rainstorms had partially exposed. Small summoned his colleagues, and further inspection revealed other bones still in place in the soft rock. Members of the party removed enough material to verify the find, but further work had to be discontinued temporarily. August was too late in the season to begin excavation, so the site was covered with plastic, tarps, and layers of dirt to secure it against the elements. That winter at the University of California in Berkeley, researchers determined that Small had discovered not just a dinosaur but a new genus and species. 1

Led by Robert Long of the University of California's Museum of Paleontology, the contingent was back the next spring, anxious to learn more about the new dinosaur. Excavation revealed a remarkable find. On June 6, 1985, the paleontologists removed from its 225-million-year-old burial ground the skeleton of a small dinosaur, about the size of a large dog. Given the fanciful name of "Gerti," this newest dinosaur was the oldest articulated dinosaur fossil from the area that could be dated with some degree of accuracy. Along with the relatively intact skeleton of Gerti, further digging revealed the remains of several other small dinosaurs. The discovery, Long explained, represented "the first definite evidence that dinosaurs lived as long ago as 225 million years or more"-in a time called the Upper Triassic period, when dinosaurs were making their first appearances.2

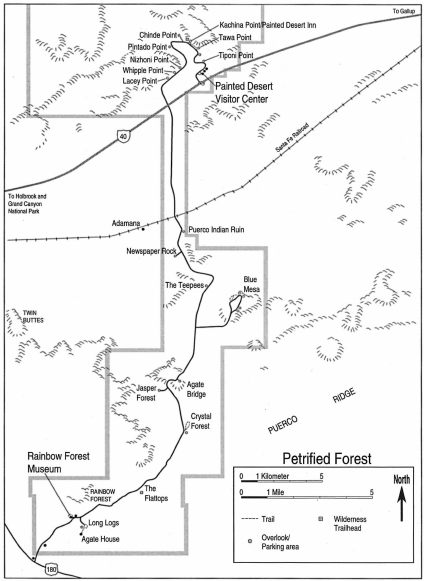

Petrified Forest National Park (Map by Ronald Redsteer, courtesy of the Bilby Research Center, Northern Arizona University)

Researchers covered the collection of bones with tissue paper and burlap soaked in plaster, preparing it for removal from the site. A powerful Sikorski helicopter was used to lift the bundle from the floor of the Painted Desert to Chinde Point. There the 1,200-pound slab of Triassic earth and bones encased in twentieth-century burlap and plaster was loaded into the craft's cargo hold for its flight to the Museum of Paleontology at Berkeley.

The rocks that yielded Gerti's skeleton belonged to the Chinle Formation, which was deposited 220 to 225 million years ago near the end of the Triassic period of the Mesozoic era. The Chinle is hardly composed of exotic elements. "To begin with," one geologist writes, it is "nothing more than an accumulation of mud and silt along with a little sand and gravel." 3 More specifically, a variety of sedimentary rocks make up the Chinle formation; most of them are soft, fine-grained mudstone, siltstone, and claystone, compressed by the passage of time and overlying rocks that have since eroded away. Beds of harder and coarser sandstone and conglomerate also occur, and near the top of the Chinle is a series of limestone beds. The name of the formation comes from the Navajo village of Chinle near Canyon de Chelly, where, in 1917, H. E. Gregory first described well-exposed deposits in Chinle Wash. In the vicinity of Petrified Forest, the formation is more than eight hundred feet thick.4

The colorfully banded rocks, so characteristic of the Chinle, exhibit a subtle spectrum of pastel colors. In the Painted Desert, the section of Petrified Forest National Park north of the Puerco River, the dominant colors are shades of pink and red, but combinations of minerals and other substances produce muted tones of blue, gray, brown, and even white. Iron oxides are responsible for variations of red, decayed plant and animal remains contribute to grays, and gypsum accounts for the white. Elsewhere in the park are softly rounded hills, ranging in color from chocolate hues to purple and gray. At some locations, the muted shades of badlands slopes stand in vivid contrast to stark brown or white sandstone ledges.

Even after a comparatively brief time, erosion can transform the Chinle into badlands-arid terrain Virtually devoid of any vegetation. No stable soil mantles the variegated colors, and in this "landscape of destruction," as one observer describes the Painted Desert, the surface is always new, always in the process of creation. Here, geologist Matt Walton writes, "only form and living process are stable and substance is transitory."5 Rainfall at Petrified Forest, only about nine inches annually, often comes as torrential cloudbursts that produce raging flash floods. The murky water is heavily laden with abrasive rock fragments and surges through normally dry arroyos, slicing the land into intricate mazes of narrow ravines, crests, and pinnacles. Because of the rapid erosion, few plants establish a foothold; no roots develop to bind the soil together. The ground itself contributes to erosion; not only does the earth here lack organic material to sustain vegetation, but soft, porous bentonite also is abundant in the strata. This clay absorbs great amounts of water, then disintegrates into a fine, flowing mud. When dry, it again hardens, only to be sculpted away by the next torrential rain.

Water continues to shape the surface of the Chinle in the winter, when rain or melting snow seeps into cracks and crevices in rocks. Upon freezing, the water expands, widens the crack, and further weakens the rock. Eventually a portion breaks away, tumbling into a gully where later runoff will wash it away. Wind, too, has shaped the landscape of Petrified Forest. Spring's blustery winds sweep across the area, transporting fine sand and dust over considerable distances. At some locations, steep-sided buttes and mesas rise from the surrounding flat terrain; their cap rocks of sandstone or lava resisted the wind while the softer, underlying rock eroded much faster. Blue Mesa and the Flattops owe their appearances to such phenomena.

The cycle of erosion continues year after year. The steeper slopes in the park lose about a quarter of an inch of soil annually. Less than half that amount disappears from the gentler hillsides, and still less is blown from level areas. The Puerco River and its tributaries unceasingly wash away bits of the Triassic landscape, and much of the sediment is deposited in the ephemeral river's broad valley. Over the years, some of the material has been swept into the Little Colorado River and then through the Grand Canyon, eventually ending up in the Gulf of California.6 Within the park, erosion has exposed more and more of the petrified logs for which it is famous. And those thousands of huge stone trees attest to a climate virtually the opposite of the high desert of contemporary northeastern Arizona.

Early in the age of dinosaurs, 225 million years ago, Arizona was a tropical lowland and was located some seventeen hundred miles closer to the equator than it is today. According to the theory of plate tectonics, the earth's present continents once had been joined in a supercontinent that we call Pangaea, meaning all earth. From it, today's land masses eventually separated and drifted off to the positions they now occupy. In the Triassic period, just as the drifting began, present North America rested far to the south of its present location, at about the same latitude as Panama.7

Northeastern Arizona was then a broad, relatively flat coastal plain, dotted with swamps and ponds and laced with muddy streams. Its tropical climate sustained a rich growth of plants. To the south and southeast rose a chain of volcanic mountains, the Mogollon Highlands, while much of present California and Nevada were inundated by the sea. Numerous streams arose in nearby mountains and meandered across the plain, gradually depositing sediment in their channels and floodplains. Trees and logs washed down from the highlands and over the years became mired in mud and covered with sediment. At other places floodwaters carried trees beyond riverbeds. The collections of trees eventually became waterlogged, sank to the bottoms of marshy lagoons, and were buried in the Triassic muck. 8

Seeds and leaves from local plants accumulated as well, and some of that material found its way to the bottoms of shallow lakes and shifting streams. as Mogollon streams continually deposited loads of sediment, burying additional plants and animals, the Chinle Formation grew thicker. Like trees and logs, animal remains were fossilized and exposed by erosion centuries later. This slow and nearly continuous accumulation of sediment went on for millions of years, and the Chinle was the result.

The precise course of events in Petrified Forest following the deposition of the Chinle Formation remains unclear, because erosion has removed much of the evidence. Periods of deposition alternated with periods of erosion, and, as paleontologist Sidney ash notes, the presence of marine strata in nearby places indicates that the sea probably covered the area in the Cretaceous period. For a time in the early Cenozoic, Petrified Forest experienced deep erosion, but conditions changed near the end of that era. The Chinle was buried beneath another formation, the Bidahochi, which consists mainly of soft, light-colored sandstone, claystone, and siltstone, and some hard beds of lava. At about the same time, volcanic eruptions occurred sporadically, covering the earlier strata with lava and ash. These, in turn, were later covered by sediment deposited by streams. Erosion then eventually removed most of the Bidahochi Formation within Petrified Forest and cut into the Chinle, too, exposing vast quantities of petrified wood and other fossils. 9

Environmental conditions-temperature, moisture, oxygen, content of sediment, depth of burial, and other factors-all determine the rate of fossilization. Most of the wood and bones in Petrified Forest were in fact petrified, that is, turned to stone by a process in which practically all of the organiC matter is replaced by minerals. The fossil retains the external shape of the object but little of its internal structure.

The process of petrification is a complex one that is not completely understood, but the following chain of events occurred. Once buried in waterlogged sediment, the trees underwent a process of replacement. as silicon-rich water percolated through the logs and bones, the silicon came out of solution and combined with oxygen to produce minute crystals of quartz within spaces in the tissue. In most of the fossil logs, the tissue was filled or replaced by quartz, and the trunks were completely petrified. In some instances-in hollow logs or in cracks of otherwise solid pieces-the growth of quartz crystals was not restricted. Such cavities within the wood might be lined with large crystals of amethyst, rose quartz, smoky quartz, or rock crystal quartz. Nineteenth-century treasure hunters particularly prized such finds, often using dynamite to dislodge the valuable crystals. The silicon-rich water also contained other elements that gave the fossil wood a variety of colors. Iron yielded shades of red, yellow, brown, and even blue. Carbon, sometimes manganese, added black; cobalt and chromium, though rare, produced blues and greens. Manganese also provided varieties of pink. 10

The process was a slow one, and the Triassic swamplands proved ideal for the transformation of the fallen logs into brightly colored silicified trees. The key to the change was the volcanic ash-the natural source of silicon. Its breakdown yields large amounts of silicon in solution. "Time and slowly moving stagnant water did the rest," a geologist comments. 11 Most small items, such as leaves, seeds, cones, pollen grains, stems, and even fish scales, have been preserved as compression fossils-thin films of carbonaceous material that remain when a leaf, for example, is buried in sediment and flattened by the weight of overlying rocks. When the encasing rock is split, the fossil appears as a thin layer of black paint on the surface. Such fossils exhibit considerable detail and are valuable aids to scientists in their reconstruction of ancient plants and animals. 12

Petrified trees are, of course, the region's best-known treasure and easily the most visible plant fossils in the park. Most of the logs are conifers-cone-bearing trees-and they normally grew to a height of eighty to a hundred feet, with trunks measuring three to four feet in diameter. Some attained heights of two hundred feet, and their diameters reached ten feet. None of these ancient trees are now standing-to the disappointment of visitors who anticipate groves of stone trees. No complete tree from roots to crown has ever been found within the park. In fact, trunks invariably are battered and worn. No limbs are evident, and there is little or no bark, indicating that most were carried some distance by streams before being buried and petrified. A few upright stumps have been found at different locations in Petrified Forest. They are only a few feet tall, and the roots clearly extend downward into the ground. Their existence suggests that small groves of trees were growing in the area when the Chinle Formation was deposited.

Most of the petrified logs and stumps are Araucarioxylon arizonicum and are related to the modern Norfolk pine and Monkey Puzzle tree, both of which now are used Widely in decorative planting. Well-preserved trunks of Araucarioxylon show clearly that branches were restricted to the very tops of the trees. At Blue Mesa, groups of petrified stumps, some of them five feet in diameter, indicate that these ancient trees grew only ten to fifteen feet apart. Consequently, shading by neighboring trees suppressed branch growth, producing a dense, closed canopy of trees with small crowns. The ancient Araucarioxylon forest very likely resembled modern redwood forests along the Pacific Coast13 Two additional types of silicified trees, Woodworthia arizonica and Schilderia adamanica, occur in small numbers in the Black Forest in the northern part of the park, as well as at other locations. Schilderia typically were small, growing to heights of only twenty to thirty feet. Woodworthia, in contrast, were larger, perhaps fifty feet tall with trunks three feet in diameter.

as colorful and impressive as the petrified logs are, they are not as important as the less visible fossils, such as stems, cones, seeds, and pollen grains. Dr. Sidney ash of Weber State University has studied the area's paleobotany for years and notes that petrified logs account for only a small percentage of the area's ancient plants. of two hundred species of plants identified, seven are based on petrified wood, while sixty have been identified on the basis of compressed leaves, seeds, stems, and cones, and the rest from pollen grains, spores, and other minute parts. All of the plants that flourished in Petrified Forest in the Upper Triassic are extinct, but modern descendants of some of them live in humid, tropical parts of the world. With the exception of flowering plants, which appeared on the earth later, most of the major plant groups are represented in the Chinle Formation. Some of the ancient plants resemble their modern descendants; others are unfamiliar and sometimes bizarre. 14

Horsetails, or scouring rushes, commonly occur in the Chinle at a number of places; both the fossil and the living plant in this group have straight, jointed, hollow stems. Some of the ancient horsetails grew twenty to thirty feet high and had diameters offourteen to sixteen inches. (Today's horsetails, in contrast, rarely grow beyond ten feet.) Ferns also were abundant throughout the Chinle, as were cycads-primitive tropical plants that resembled a pineapple with palmlike leaves growing in a top cluster. Scientists have found abundant leaves from a similar plant, Bennettitales, an extinct group that may have been related to the cycads. Other plants have proven difficult to classify; one of them is deSignated Dinophyton spinosus-the "terrible spiny plant." 15

Insects and their relatives were abundant throughout the ancient landscape. The cockroach, so well known and detested in the twentieth century, also was at home in the Triassic, as indicated by compressions that scientists have found. Various beetles, too, made their homes there. Some petrified logs bear the holes and scars left by wood-boring insects, and some fossil leaves appear to have been nibbled on. 16

Analysis of plant fossils has provided information about the size and habitat of the original plants as well as data about the climate. Growth rings on petrified trees indicate the length of growing seasons, for example. In addition to plant fossils, scientists have found remains of clams, snails, clam shrimp, horseshoe crabs, crayfish, fish, amphibians, and several kinds of lizards, not to mention early dinosaurs. The study of fossilized animal remains has provided clues about the dimensions of some extinct creatures and information about their environment. The size and shape ofleg bones indicate how an animal moved; teeth suggest the nature of its diet and also its size.

The shallow waters of streams and ponds were home to shoals of clams and other freshwater mollusks. Above them swam a variety of fishes, most of them primitive species, generally less than a foot long and covered with rectangular or diamond-shaped scales. Some, like Turseodus, were elongated and tapered at both ends, similar to today's sturgeons. Others, such as Hemicalypterus, were narrow and deep-bodied like the modern Mississippi gar. With its heavy enameled scales, the gar proVides an impression of the body covering typical of Triassic fishes. 17

A close relative of the modern Australian lungfish inhabited the region's streams and lakes. Named Ceratodus, it was widely distributed in Triassic time, and its habits were similar to those of its modern descendants. When streams and ponds dry up and the remaining water stagnates, lungfish (which indeed have lungs) surface to gulp air and thereby survive. The presence of Ceratodus suggests that the region's climate then alternated between humid seasons and dry months when streams and lakes were low.18 Researchers have found remains of two kinds of sharks, neither of which was particularly large. Undoubtedly the most formidable of the fishes in the region was Chinlea, which one scientist describes as "the top of the food pyramid among the fishes in the Chinle." Chinlea could grow to five feet in length and weigh as much as 150 pounds, although most were less than two feet long. Regardless of its size, Chinlea's dominant characteristic was its complement of large, sharp teeth, which made it a feared adversary. 19

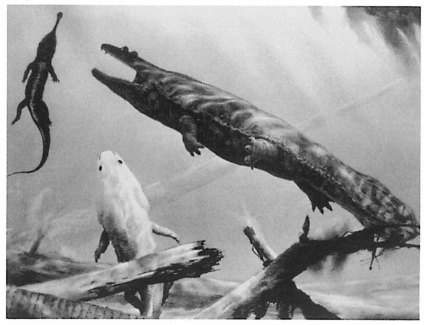

Among four-legged animals, only amphibians and reptiles have been found thus far in Petrified Forest's Triassic landscape. Metoposaurus resembled vaguely a giant salamander and was one of the more common amphibians of the region. It grew to a length of six to eight feet and was possessed of an inordinately large, flat skull. Its jaws held numerous small, sharply pointed teeth, indicating that Metoposaurus was a fish eater. Weighing about half a ton, its heavy body and great head obviously taxed its short weak legs, which could not bear its weight on dry land. Typically, Metoposaurus spent its time sprawling in mud and water-a habitat to which it was better adapted. Researchers occasionally have come across large concentrations of this giant salamander-like creature, usually in water holes where they died when the water dried Up.20

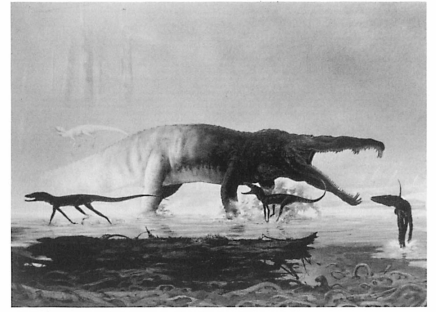

Phytosaurs were common in the ancient environment of Petrified Forest. The smaller, lightly built figures in the foreground are sphenosuchian reptiles, direct ancestors of today's crocodiles. (Illustration by Doug Henderson, photograph courtesy of the Petrified Forest Museum association)

The dominant inhabitants of the waterways were phytosaurs, crocodile-like reptiles that averaged about seventeen feet in length, with the largest reaching thirty feet. Their long jaws were eqUipped with numerous sharp, conical teeth, and they probably ate anything they could catch. Fish as well as any animals that lived near the water were their natural prey. Despite the superficial resemblance to modern crocodiles, phytosaurs were not their direct ancestors. The body and tail of phytosaurs were covered with heavy, bony plates. Nostrils were located on a dome just ahead of their eyes-an arrangement that allowed these animals to remain submerged for long periods of time while patiently awaiting their prey. Fossil remains of phytosaurs found in Petrified Forest are identical to specimens discovered elsewhere in North America, Germany, and India. Similarly, the bones of Metoposaurus are duplicated by fossils uncovered on this continent and in North Africa and Germany. The similarities, E. H. Colbert points out, represent additional evidence of the juncture of western Europe and Africa (to which India then was jOined) with North America in Triassic times. 21

Metoposaurs were among the largest of the ancient animals in Petrified Forest. These giant amphibians spent much of their time in marshes awaiting prey. (Illustration by Doug Henderson, photograph courtesy of the Petrified Forest Museum association)

A variety of reptiles, both herbivores and carnivores, inhabited the higher ground around the lakes and streams. Typothorax and Desmatosuchus were thecodonts related to phytosaurs. Both of these plant eaters reached lengths of ten to fifteen feet and were armored with large plates. Also, sharp lateral spikes protruded from their bodies, perhaps as defenses against their phytosaur cousins. The dominant herbivore of the time was Placerias-a member of a reptile group called dicynodonts that once ranged over much of the world's land areas. By the Triassic period their numbers were dwindling, and Placerias was one of the few remaining large members of the species. It was about the size of an ox and was among the largest animals living on land at that time; the largest dinosaurs had not yet made their appearance. Like most herbivores, Placerias had a broad, barrel-shaped body and was likely an awkward animal, one authority speculates. Most of its time was spent foraging for vegetation. 22

In contrast to the region's plant eaters, the carnivores Hesperosuchus and Coelophysis were small creatures that probably fed on small game and even insects. Clearly they were no threat to a brute like Placerias. A small thecodont, Hesperosuchus was equipped with sharp teeth and was an active predator, capable of walking on its hind legs while using its long tail as a counterbalance. Its small forelimbs had facile hands that were used in foraging. Coelophysis was one of the earliest dinosaurs-a miniature edition of the giants that evolved later. Six to eight feet long, it weighed only forty to fifty pounds. It walked in a semi-erect position, its long, slender tail effectively balancing the weight of its body. Strong hind legs ended in a three-toed foot that left an imprint similar to the footprint of a bird. Its forelimbs were small and equipped with tiny clawed hands that allowed Coelophysis to catch and hold its prey. Its backbone was supple and its neck comparatively elongated. In short, Coelophysis represented a "typical example of the ancestral dinosaurs from which the great giants of the later Mesozoic Era evolved," according to one expert on the region's dinosaurs.23 It was the first dinosaur found within the boundaries of Petrified Forest National Park. Its fossil remains were recovered in 1982, and a half dozen dinosaurs, including Gerti, have been discovered since.

Coelophysis is similar to fossils found in Connecticut, and it also has a close counterpart in the Upper Triassic deposits in Rhodesia. as in the cases of the lungfish, phytosaurs, and large amphibians, evidence suggests a close relationship among fossils found in Arizona, eastern North America, Africa, central Europe, and India. All of this buttresses the validity of the theory of plate tectonics and drifting continents, Colbert argues, and the fossils of animals found in the Chinle Formation in Petrified Forest have contributed significantly to this new view of the earth.24

Fossilization is a hit-or-miss proposition. The creatures that inhabited the swamps and streams of the Chinle Formation were preserved only occasionally. Preservation of the remains of such animals requires that they die in a place that is inundated with sediment before the carcass decomposes. Normally, when an organism dies, its remains decay or are eaten by other animals. Even when fossils form, they can be destroyed by floods, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, or other natural occurrences. A great many fossils were formed in Petrified Forest simply because the right conditions were present.

The Triassic trees and organisms lay entombed in rock for millions of years. Then, beginning 60 million years ago, episodes of mountain building created the Rocky Mountains and the Sierra Nevada, giving western North America its modern form. The violent and complex movements in the earth's crust also affected the area that is now northern Arizona, which was raised slowly thousands of feet above its original sea-level location. With the change in elevation came an equally pronounced change in the climate. The onetime tropical lowland became part of a high desert-an extensive uplifted area called the Colorado Plateau. Forces of erosion soon were operating; and in time rain, wind, and frost began redUCing the surface rock. as the Bidahochi and Chinle Formations gradually eroded, the ancient stone trees weathered out of the surrounding rock.

We know today what early visitors could not-that Petrified Forest's ancient environment was a crucial time in the earth's evolution. Early dinosaurs were just making their appearance, replaCing earlier thecodonts that had dominated the landscape. Every new discovery, whether the unearthing of an early dinosaur or the meticulous screening of soil for spores or grains of pollen, adds incrementally to our knowledge of the ancient ecosystem. Today's national park preserves not just an unspoiled portion of America as it existed before humans arrived in the area. Petrified Forest protects an environment that existed before people even appeared on earth. The gradual erosion of the Triassic Chinle Formation provides us with an imperfect view of the earth long before humans could alter its environment.

The first people to observe the clusters of petrified trees were ancestors oftoday's American Indians. When Navajos moved into the Southwest several hundred years ago, they came across numerous ruins that ancient inhabitants had abandoned. These prehistoric pueblos clearly were not the work of the Navajos' own ancestors, and they consequently referred to the ancient dwellers of the region as Anasazi, a term that translates roughly as ..enemy ancestors" or simply" ancient ones."

Archaeologists adopted the Navajo name and still use it to describe the prehistoric people who settled in Canyon de Chelly, Chaco Canyon, Mesa Verde, and other places throughout the four corners region. Anasazi cultural development spans as much as fifteen centuries. Archaeologists designate the earliest Anasazi sites as Basketmaker II (from as early as 100 B.C. to A.D. 500-700)-a time when the Anasazi typically lived in caves and grew crops of squash and corn while also engaging in hunting and gathering. Their culture became increasingly sophisticated over the centuries. The deSignation Basketmakers, of course, derives from their expertly made baskets, although the Anasazi began making pottery as early as the sixth to eighth centuries. From the eighth to the fifteenth centuries, their culture was based on pueblos. Initially, houses simply were clustered more tightly, often sharing adjoining walls. By the eleventh to the thirteenth centuries, the Anasazi were living in large masonry villages with buildings sometimes reaching several stories high. These centuries represented the high point of their architecture, basketry, and pottery, and were a time of extensive trade with neighboring groups. Even larger villages became common in the following two centuries, when settlements housed hundreds, perhaps thousands, of people. 25

as early as the twelfth century, though, the Anasazi began moving south, often to the mountains of present Arizona and New Mexico. By 1300, the San Juan region had been abandoned completely, and in the following centuries the migration continued as the northernmost Anasazi joined relatives living in the Hopi mesas, along the little Colorado River, near Zuni, and along the Rio Grande. The Spanish intrusion, beginning with Coronado's arrival at Zuni in 1540, marks the beginning of the historic period.

The Anasazi were not the only prehistoric people to settle around Petrified Forest. The lower Puerco River Valley lies in a geographic frontier region between several cultures. Not only the Anasazi but also the Sinagua and Mogollon peoples left their impact on the land. Whereas the Anasazi primarily inhabited the high plateaus and canyons around the Four Corners, the Mogollon were mountain dwellers along the present Arizona-New Mexico border. They raised some corn, beans, squash, and, later, cotton, and probably engaged in more hunting and gathering than did the Anasazi. Until about 1100 the Mogollon settlements consisted of pithouses; settlements were small and long-lasting. After that date, the Mogollon settlement patterns changed, although not consistently, and the people also built surface structures. population tended to converge into fewer but larger settlements along major drainages. By the middle of the fifteenth century, the Mogollon had abandoned their earlier sites, and remnants of the groups went off to Zuni and Acoma. 26

The center of Sinagua culture was some distance to the west of Petrified Forest, near the present site of Flagstaff, Arizona. Although only a few Sinagua sites have been excavated, evidence indicates that these people lived in small settlements consisting of pithouses. Their population grew dramatically after Sunset Crater erupted in 1060, covering the earth with a layer of cinders that increased soil fertility and productivity. The Sinagua also underwent Significant cultural change as they interacted more fully with nearby peoples.

In the twelfth century, Sinagua settlement patterns changed, as did those of the Anasazi and Mogollon, and large pueblos replaced pithouses. Although population had peaked during those years, after 1200 it declined rapidly and the Sinagua departed the Flagstaff area settlements for the Verde Valley to the south. By 1300- 1350 the former area was virtually abandoned; the only remaining large northern Sinagua pueblos were located around Chavez Pass.27

Although Petrified Forest was the site of significant cultural mingling, it never emerged as any kind of a cultural center. Such blending, archaeologist Yvonne Stewart explains. "is not uncommon, but it has rarely been studied and is poorly understood." Archaeologists have analyzed the influence of cultural groups upon one another around Petrified Forest. an area that one researcher describes as a "frontier" between cultural groups. They generally agree that such interaction is evident from the time of the earliest settlement to the latest. 28

The oldest habitation site within the present national park is Flattop Village, which the Anasazi occupied prior to A.D. 500. This collection of pithouses located on a mesa in the southern part of the park was probably only a summer residence-a place for the Anasazi to live while they farmed adjacent land. On the valley floor about six miles to the northeast is Twin Buttes Village, which was inhabited from the sixth to ninth centuries. pottery and a few items made from shell indicate that the residents participated in regional trade that extended as far west as the Gulf of California.

A small Pueblo III site (1100-1250) is perched on a low knoll in Rainbow Forest near the south entrance to the park and is called, appropriately, Agate House. It is constructed entirely of blocks of petrified wood, as are a number of other ruins in the vicinity. Agate House contains only a few rooms and probably was used only for short periods of time, archaeologists believe. Another site from the same period, also in the southern part of the park, is a Mogollon campsite near Jim Camp Wash.

The thirteenth century was a period of widespread drought in the Southwest, and important changes in Indian cultures occurred as inhabitants adapted to the new environment. Despite a general lack of rainfall, some areas retained enough moisture to sustain agriculture. Puerco Indian Ruin is one such location-a 125-room pueblo that was first occupied in the twelfth century. Its residents farmed the floodplains and terraces along the stream, growing beans, squash, and corn. At its height, the village sustained perhaps sixty to seventy-five people, and it had cultural ties with settlements to the west. Its residents left during the drought, but the pueblo was occupied again during the fourteenth century. Rainfall had increased by that time, but precipitation was heaviest in the winter months. The meager summer rainfall came in short, violent thunderstorms that eroded the terraces along the Puerco River and flooded the adjacent farmland. as food production fell off, inhabitants systematically departed by 1400. Investigators have found no evidence of violence or epidemic to suggest that the people were driven away from their pueblo. According to Hopi tradition, the Puerco people moved northward and took up residence on the Hopi mesas. The archaeological sequences indicate that the area now embraced by Petrified Forest National Park was a cultural melting pot. Located between the Anasazi's high plateau and the Mogollon Rim, the region experienced a variety of influences from surrounding cultures. 29

When Europeans viewed the region for the first time in the sixteenth century, the confines of the present Petrified Forest National Park were devoid of any settlement. In July of 1540, Francisco Vasquez de Coronado and Fray Marcos reached the Zuni village of Hawikuh. From there Coronado dispatched parties to investigate the surrounding territory. One such contingent, led by Don Pedro de Tovar, was the first to reach the Hopi mesas in northeastern Arizona; another detachment followed Garcia López de Cardenas westward to the Grand Canyon of the Colorado. Neither group turned up any evidence of great wealth, as Coronado had hoped they would. The only evidence of the Spanish presence near Petrified Forest is a brief reference to Desierto Pintado.

If other white men passed through the area before the middle of the nineteenth century, none left an account. Petrified Forest eventually passed into American ownership in 1848 as part of the Mexican cession following the U.S. war with Mexico. Little time elapsed before the new American owners were methodically exploring and surveying their new domain, and in the process their soldiers and scientists came across the deposits of petrified trees that wind and rain had uncovered during the previous centuries.