2

"QUITE A FOREST OF PETRIFIED TREES"

I've trapped beaver on Platte and Arkansas, and away up on Missoura and Yaller Stone; I've trapped on Columbia, on Lewis Fork and the Heely.... I've trapped in heav'n, in airth, and h-; and scalp my old head, marm, but I've seen a putrified forest.

Moses ("Black") Harris, mountain man

Lieutenant James H. Simpson of the United States Corps of Topographical Engineers was the first to record the discovery of petrified wood in the Southwest and to provide a description of the rock that encased it. His 1849 discovery occurred not in Petrified Forest but in similar terrain about one hundred miles to the north in Canyon de Chelly. Simpson was no scientist and found the specimen simply by chance. He provided only a brief description of the fossil, including it with his expedition report. Modern scientists, having read the account, acknowledge that the Canyon de Chelly fossil was of Triassic age. 1

Two years later, another topographical engineer led a detachment through northern Arizona and New Mexico, this time in search of a new route across the Southwest to California. Captain Lorenzo L. Sitgreaves had orders to explore the course of the Zuni River to its supposed confluence with the Colorado and to report on the general characteristics of the region as well as on the river's potential for navigation. In September of 1851, Sitgreaves traveled from Zuni Pueblo westward to the Little Colorado River, making camp twice on that stream only a few miles south of the present park boundary. On September 28 the captain abandoned the soft, muddy terrain along the river for higher ground, where his men soon came across "masses of what appeared to have been stumps of trees petrified into jasper, beautifully striped with bright shades of red, blue, white, and yellow." Much of the area, he reported, was strewn with pebbles of agate, jasper, and chalcedony.2

Samuel Washington Woodhouse, the thirty-year-old physician and naturalist with the expedition, also commented on the petrified wood. One of the trees, he noted, was broken into pieces as ifit had fractured in falling, and its roots faced uphill. Neither Woodhouse nor Sitgreaves offered any explanation for the origins of these fossilized trees, and Richard Kern, who served as the expedition's draftsman, penned only the laconic observation "Fossil tree purple color."3 Woodhouse, a member of the Academy of Natural Science in Philadelphia, selected three specimens of petrified wood during the expedition's brief visit to the site and in 1859 presented them to the academy. Two of the pieces were lost over the years, but the third still rests there among the institution's collections.4

Along the Little Colorado, the Chinle Formation is exposed extensively, giving the terrain around Petrified Forest and Painted Desert its characteristic range of pastel colors. For centuries, wind and rain had slowly uncovered the immense deposits of petrified wood, and Sitgreaves and Woodhouse were among the first Americans to venture into the region. If anyone can be deSignated as the "discoverers" of the Petrified Forest, that title ought to go to Sitgreaves and Woodhouse. Their discovery of the petrified wood was, of course, incidental to the main task of their expedition, and that perhaps explains why the men commented so briefly on their find. The captain would have missed the trees entirely had he not led his contingent out of the riverbed in search of higher and firmer ground on September 28.

The Sitgreaves party focused on exploration, but the next expedition to visit Petrified Forest operated under a much broader mandate. In an attempt to resolve the intense debate over the route of the country's first transcontinental railroad, Congress in 1853,) sought an impartial solution by establishing the Pacific railroad surveys. The legislation placed the surveys under the aegis of the Corps of Topographical Engineers and directed reconnaissances along four potential routes. of these, a southern road along the thirty-fifth parallel led through northern New Mexico and Arizona, proceeding from Albuquerque to Zuni and then westward through a portion of the Little Colorado River Valley.

Because Congress wanted extensive information about the terrain along the routes, each survey included expert scientists. Individual commanders typically chose their civilian scientists after consultation with Secretary of War Jefferson Davis and his special assistants, Major W. H. Emory of the Topographical Engineers and Captain Andrew A. Humphreys, head of the newly created Bureau of Western Explorations and Surveys. But the Smithsonian Institution, various learned societies, and leading scientists also had a voice in determining the scientific contingents. Louis Agassiz secured the appointment of his colleague, the Swiss geologist Jules Marcou, to the thirty-fifth parallel survey. Similarly, on the recommendation of the great Prussian geographer Baron Alexander von Humboldt, Heinrich Baldwin Möllhausen jOined that survey as an artist and topographer. Rounding out the civilian contingent were a physician and a surgeon, both of whom doubled in scientific capacities, an astronomer, engineers, surveyors, and a computer who recorded distances. 5 Leadership of the thirty-fifth parallel survey fell to Lieutenant Amiel Weeks Whipple of the Topographical Engineers.

Whipple left Albuquerque on November 8 and began the trek across northern New Mexico. By the end of the month, his contingent had entered the eastern part of present-day Arizona, and on December I they crossed the Puerco River. On the following day the party moved on westward, stopping for the night on a low ridge above a nearly dry streambed that Whipple named Lithodendron Creek. The terrain around the camp was strewn with pottery fragments, and Whipple commented on the numerous pueblo ruins in the area. During their short stay at the site, the men partially excavated the walls of one of the "stone houses." If these remnants of an earlier civilization temporarily engaged the members' imaginations, the discovery of "quite a forest of petrified trees" further intrigued them. None of the trees were standing, and most were buried in red marl, as Whipple described the soil. Some of the logs appeared charred, as if they had been burned before petrification. The main portions of these trees were a dark brown color, Whipple reported, while the smaller branches exhibited a reddish hue. Smaller fragments covered the surface for miles around.6

Whipple had led his party into the Black Forest-a deposit of petrified wood located in the Painted Desert in the northern reaches of today's national park. Though fossilized wood is plentiful here, it lacks the diversity and colors exhibited in the park's other "forests," such as Rainbow Forest and Crystal Forest. Still, Whipple wrote that the colors were "as rich and bright as I have seen." 7

Baldwin Möllhausen, for whom exploration of the West took on the aspect of a romantic adventure, was much more effusive in his description but also remarkably perceptive. "We really thought we saw before us masses of wood that had been floated hither or even a tract of wood land where the timber had been fallen for the purpose of cultivation," he wrote in his diary. Petrified trees of all sizes were scattered over the terrain, including some stumps "with roots that had been left standing."8 The German's comments are Significant. His observation that the petrified logs appeared to have floated into Lithodendron Wash agrees with standard explanations about their origins. Möllhausen was also correct in reporting standing stumps among the more numerous prostrate logs. Later discoveries of such stumps in various locations of the park confirmed that some of the fossil trees had in fact grown in the area.

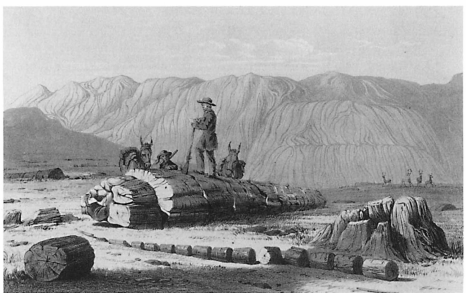

Möllhausen noticed that most of the long, petrified logs appeared to have been cut into shorter pieces, many of them only a few feet in length. After examining the trees more closely, he concluded that over the years, torrents of water rushing through Lithodendron Wash had left the logs virtually bare of limbs. In his diary, he explained that many of the larger ones were hollow and looked burnt. They were mostly of a darker color, but it was still possible to discern the bark, burnt areas, rings, and cracks that had occurred in the pieces. Whipple had made no provisions for hauling the huge logs, so the men had to be content with collecting fragments from as many different fossil trees as possible. The pieces, Möllhausen wrote, indicated the variety of petrifications in the area, and he regretted that there was no way to convey the dimensions of the blocks of petrified wood.9 His own sketches had to suffice to depict the size and characteristics of the fossil logs.

This sketch of Petrified Forest was made by Baldwin Möllhausen during the Whipple Expedition of 1853 - 1854. Note the stump in the lower right-hand corner, suggesting that some trees were growing at the site. (From Möllhausen's Diary of a Journey from the Mississippi to the Coasts of the Pacific, photograph courtesy of Museum of Northern Arizona)

Significantly, the party searched in vain for impressions of leaves and plants but found only some "tree-like ferns ." The area contained little vegetation of any kind, and consequently the men passed a cold night encamped near Lithodendron Wash. Nearby were what looked like masses of wood, but "they were the kind that one could only get a spark out of by means of a steel," Möllhausen complained. When the expedition followed down the streambed the next day, the men observed additional deposits of petrified wood along the route. And, like twentieth-century tourists, they could not resist the temptation, Möllhausen wrote, "to alight repeatedly and knock off a piece, now of crimson, now of golden yellow, and then another, glorious in many rainbow dyes." 10

More sophisticated than Möllhausen's account was the description by Jules Marcou, who had earlier published a controversial geological map of the United States. Although Louis Agassiz had praised the work and recommended Marcou as a geologist with the Whipple survey, the map had engendered harsh criticism from geologists James Dwight Dana and James Hall. W. P. Blake of the Office of Railroad Explorations and Surveys also disputed some of Marcou's findings.11 Marcou's "Resume and Field Notes" in French were published in parallel columns with Blake's translation in the third volume of the railroad survey reports. His observations are particularly important because Marcou was the first professional geologist to view Arizona's petrified forests and also the first to publish a description of Triassic plant fossils in the Southwest. He recognized that the petrified wood in Lithodendron Wash was coniferous and noted that tree ferns and Calamodendron (fossil stems) also occurred. Finally, Marcou correlated the rocks in Lithodendron Wash with the Triassic Keuper Formation in Germany, and that correlation proved essentially correct. "We are in the middle part of the Trias," he recorded in his notes. "No Jurassic." 12

Although W. P. Blake had not accompanied the expedition, he relied on its reports, illustrations, and specimens to write his own review of the geology of Whipple's route. In it he denied that Marcou had conclusively established the age of the rocks that encased the petrified trees in Lithodendron Wash. Further, he questioned the correlation with the Triassic formation in Europe. Marcou did not identify the terrain as Triassic on the basis of fossils found in Arizona. He simply recognized the similarity of the landscape around Petrified Forest to that in Germany with which he was familiar. Blake was correct in noting that Marcou had not offered any fossil evidence for his contention. 13

Like the other Pacific railroad surveys, Whipple's examination of the thirty-fifth parallel route was confined to rapid reconnaissance. Consequently, the information it acquired was limited and sometimes lacking in detail. Mid-nineteenth-century paleontologists primarily were stratigraphers, intent upon plaCing formations in their proper order and correlating sequences with formations elsewhere. Their goal was to use strata to better understand the history of the earth.14 Möllhausen, in his capacity as topographer and artist, proved a valuable asset, providing many of the illustrations for Whipple's report and for his own diary. His drawings of the topography around Lithodendron Wash and his sketches of petrified trees and stumps were among the first published illustrations of Triassic plant fossils in the Southwest.

The railroad surveys informed Americans more fully about the scenery of the West. More than that, the reports represented a compendium of information about this new region. Members of the various expeditions shared common antebellum assumptions about the landscape and naively anticipated finding magnificent mountains, extensive forests, and sublime views, all of which fit within the context of nineteenth-century romanticism. From studying accounts of earlier explorers, they also knew that they could expect deserts and arid plains. From time to time, at places in the Rocky Mountains and the Cascades, the monumental scenery was overwhelming-just what artists and illustrators hoped for. In other instances the absence of greenery and the stark terrain came as a shock. Oftentimes, historian Anne Farrar Hyde has noted, "stranger kinds of scenery proved more difficult to describe," and sometimes deserts and mountain formations "stunned survey parties into descriptive silence." Whatever their experience with earlier eastern scenery and European aesthetic standards, describing some aspects of the West proved difficult. Since many expedition members were scientists, they understandably retreated to the language of science and simply produced listings of plants, animals, and geographical features. 15

This was in fact the tendency of Whipple's contingent at Petrified Forest. The lieutenant's comments invariably were terse and factual. Marcou spoke almost exclusively as a scientist, and even the romantic Möllhausen was restrained in his commentary. His illustrations are comparatively simple, unembellished portrayals of petrified logs and stumps. Earlier writers often compared American scenes to those in Europe, but in northeastern Arizona, there was no basis for comparison oflandscapes. Petrified forests, the Painted Desert, and surrounding areas had no counterpart elsewhere. The single connection with Europe's geography was Marcou's correlation of the terrain with the Triassic Keuper Formation of Germany.

Möllhausen returned to Germany late in 1854, bringing along a number of specimens of petrified wood for the German paleobotanist H. R.

Goeppert, who identified them as belonging to the coniferous species. One he named Araucarites möllhausen after its discoverer, but he neglected to publish the requisite scientific description. Consequently Möllhausen's name is not linked with the specimen. 16 Möllhausen returned to the American Southwest briefly in 1858 as a member of an expedition led by Lieutenant Joseph c. Ives and paid a last, brief visit to the petrified forests. The trek across northern Arizona provided an opportunity for Ives and geologist John Strong Newberry to examine the terrain north of the Little Colorado, and on May 7 they came across an extensive deposit of petrified wood. These fossil trees exhibited a broad spectrum of colors, ranging from brilliant red jasper to more subtle agate and opalescent chalcedony. Although the location was some sixty miles north of the Black Forest, Newberry was certain that they came from the same rock unit that encased the Lithodendron Wash fossils.17

From time to time, other reports of discoveries of petrified wood appeared in print. Franc;:ois X. Aubrey, the enterprising and well-known Santa Fe merchant, mentioned finding a number ofvery large petrified trees near the Little Colorado in August of 1854. Four years later, Lieutenant Edward F. Beale, in his report Wagon Road from Fort Defiance to the Colorado River, described several petrified trees just west of Carisso Creek, thirteen miles from Navajo Springs. Beale's expedition had occasionally followed the indistinct route left by the Whipple survey, and Beale most likely was describing fossil trees that earlier parties had observed. Similarly, in Seven Years' Residence in the Great Deserts of North America (1860), Abbe Emmanuel Henri Dieubonne Domenach described "a little forest of petrified trees" on the banks of Lithodendron Wash. His observation that the logs were brown and black in color, as if they had been burnt, suggests that he, too, had wandered into the Black Forest. 18

The Civil War interrupted scientific explorations and surveys in the Southwest. Following that conflict, the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad Company (which evolved into the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe) was chartered to build along the thirty-fifth parallel, and by the 1880s crews were laying track across northern Arizona. The little towns of Winslow, Holbrook, Adamana, and a few others grew up along the right-of-way. In the 1870S and 1880s, Mormon emigrants settled in the Little Colorado Valley, and ranching emerged as an important economic endeavor. As a conse- quence of the influx of population, the petrified trees became increasingly well known, and articles about the area appeared in regional and national magazines.

General William Tecumseh Sherman reawakened scientific interest in Arizona's Petrified Forest in 1878. During the course of a cross-country tour, the general stopped at Fort Wingate in western New Mexico Territory. In conversations with the post commander, Lt. Colonel P. T. Swaine, he asked Swaine to procure two specimens of petrified wood "suffiCiently large to be worthy of a place in the Smithsonian Institution." That duty fell to Lieutenant J. T. C. Hegewald, who found suitable fossil logs in Lithodendron Wash and forwarded them to Washington. 19

Professor Frank Knowlton of the National Museum later examined the fossil trees and concluded that they all belonged to the genus Araucarioxylon and were probably of the same species. He added that the Smithsonian specimens might be the Araucarites möllhausen that E. H. Goeppert had named in 1854. Since Knowlton could find no description of that specimen and was unable to examine the one Goeppert had deposited at the University of Berlin, he described the specimens under the name Araucarioxylon arizonicum. 20

The soldiers and scientists who had discovered and examined the petrified trees in Lithodendron Wash saw only a small part of a much larger and varied expanse of silicified wood in northeastern Arizona. The discovery of that deposit itself had been accidental, and subsequent visits to the site were generally incidental to other endeavors, such as the Whipple railroad survey. Nevertheless, the early work was Significant. Jules Marcou had correctly placed Petrified Forest in the Triassic period, an important first step in identifying the region's ancient environment.

Neither Marcou nor his detractors then realized the implications of his bold assertion. Today's scientists view the 30 million years of Triassic history as a critical time of transition-a geologic period that intervenes between an old and a new world. Some amphibians typical of Permian faunas disappeared before or during the transition from Permian to Triassic. Others, such as labyrinthodonts and therapsids, survived to become prominent Triassic faunas. Appearing at the beginning of the Triassic and continuing on to their extinction at the end of the period were the newcomers-the thecodont reptiles, "harbingers of the future," one authority has called them, whose descendants would inherit the earth during the late Triassic and the next two geologic periods.21

For the last decade of the nineteenth century, Petrified Forest was on the fringes of scientific investigation in the Southwest. Archaeologists- and in some cases untutored pothunters-actively dug into prehistoric sites in the region, and geologists similarly continued their research into the earth's history. But for the time being, that activity occurred beyond the boundaries of the present park. New discoveries of petrified wood in those years were due to the meanderings of curious travelers and enterprising businessmen.

Although a number of parties had visited Lithodendron Wash, it was not the only location in the area that contained extensive depOSits of petrified wood. By the latter part of the nineteenth century, it was not even the best known. About twenty miles south of the Black Forest and only eight miles south of Adamana station on the Santa Fe line, a broad expanse of petrified wood already was being heralded as "Chalcedony Park" by residents of Holbrook and other small towns in the vicinity. Because of its close proximity to the railroad, the so-called park attracted a growing number of visitors. In contrast to the expedition scientists who examined the petrified trees in Lithodendron Wash, few of the tourists who visited Chalcedony Park had any framework for understanding these sites. Some were awestruck, others simply puzzled by the scene.

Once tourists reached such isolated places as Holbrook, Carrizo, or Adamana, they had to depend on their own resourcefulness to reach Chalcedony Park. One of the first to publish his impressions was the Reverend H. C. Hovey, who interrupted his eastward journey aboard the California Express in 1892 to visit the site. Fearing that he might miss Petrified Forest entirely, Hovey appealed to the conductor, who arranged to stop the train briefly at whistling point 233. The conductor pointed across the desolate terrain to a windmill visible on the far horizon, identifying it as Adam Hanna's ranch, the only house within ten miles. "Maybe you can get a horse there," he told Hovey. "If not you can foot it in the morning." Moments later the California Express disappeared in the distance, leaving the clergyman and his Kodak alone in the desolate high desert. 22

Hovey successfully reached Hanna's ranch and rented a horse for the ride to the petrified forest. There he spent several days exploring the scattered deposits of fossil wood. Later he warned readers of Scientific American that no actual forest existed there, despite the tendency of local residents to boast of their Petrified Forest. Nor was there anything resembling a park, though everyone freely described the place as Chalcedony Park. Instead, the scene reminded Hovey of a logging camp, where lumberjacks had tossed the huge trees at random, leaVing them to become rain soaked and moss covered. Hovey nonetheless delighted in the brilliant petrified logs and gathered plenty of specimens to take home. "Each crystal or moss agate, or amethyst, or onyx, seems most desirable till it lies in your pocket or saddle pouch," he wrote, "and then others assert their superiority."23

Hovey departed the forest reluctantly, made his way back to Hanna's to return the horse, then flagged down an approaching train to resume his journey. Content with his pouch of glistening treasures, Hovey was convinced that "whatever marvels may have existed in the days of Arabian Nights' entertainment, none in these more modern times could rival, in its way, the petrified forests of Arizona." Like many subsequent visitors, the Reverend Mr. Hovey advocated establishing a national park there, both to protect the depOSits and to improve access to them. 24

Few visitors experienced as many difficulties as did Hovey, and most easily arranged transportation from Holbrook or Adamana. But like him, they tended to interpret the words "forest" and "park" literally. Both terms evoked precise images in the nineteenth century, and writers were determined to disabuse their readers of any images of well-groomed park-lands or tall pine forests. S. A. Miller, for example, in 1894 warned members of the Cincinnati Society of Natural History to "cast out of mind the idea of a forest, for there is none." Instead, he prepared his readers to find petrified logs broken into short pieces, some even shattered, and strewn across the landscape. The phrase "Chalcedony Park," he pointed out, was simply erroneous25

The leading nineteenth-century authority on precious stones and gems was George Frederick Kunz. He discussed Arizona's Petrified Forest in a brief article in the Popular Science Monthly, and in his well-known Gems and Precious Stones of North America he speculated about the uses and value of the chalcedony, jasper, and agate that abounded in the area. He estimated that the deposits contained a million tons of fossil wood, but only a small portion of it was suitable for decorative purposes. At that time, petrified wood had been used in only one major work-the base of a silver centerpiece that was presented to the sculptor F. A. Bartholdi. Joseph Pulitzer had selected the wood, and the Tiffany Company of New York had cut and polished it into a low, truncated pyramid that measured eleven inches square at the base and was ten inches high. It was, according to Kunz, the largest piece of petrified wood that had been cut into a definite shape in this country. He was convinced that the hard, lustrous material would be useful for various interior decorations in exclusive American homes, including floor tiles, mantles, clock cases, table tops, and similar items. 26

Popular scientific magazines invariably carried illustrations of the more dramatic features of Petrified Forest. The Scientific American Supplement of September 1889 included pictures of places that it identified as "Jasper Hill" and "Chalcedony Canyon" along with an illustration of the "Natural Bridge," now called Agate Bridge, which it described as "an entire tree converted to silex."27 Photographers never tired ofshooting it, particularly when a small crowd of tourists could be induced to pose on top.

If popular writers acquainted people with the petrified forests, they also supplied varying amounts of information that was simply wrong, albeit interesting. The writer of a column for young people in the Cambrian explained that "the great forest was petrified, not fallen as we now find it, but standing in hot or warm waters." Ages later, this imaginative writer continued, earthquakes caused the lakes to drain and also threw down the fossil trees, leaving them broken and strewn across the high desert. 28 Writing in Frank Popular Monthly in 1887, C. F. Holder suggested that nearby volcanoes suddenly spewed millions of tons of ash and lava into the forest. "The weight of the shower may have broken many trees down," he suggested, "or an earthquake felled them to the ground."29 Foremost among the proponents of the earthquake theory was the exuberant author of Some Strange Corners of Our Country and editor of Land of Sunshine, Charles F. Lummis. "I can conceive of but one power that can have mowed them down so marshalled-an earthquake of the first dimension, traveling from the crest of the continent southerly." Later, he theorized, the trees were" embalmed to perennial gems." 30 In the late nineteenth century, such explanations seemed reasonable, and ash from volcanoes, of course, did play an important role in the process of petrification. But neither volcanoes nor earthquakes were responSible for toppling the ancient trees.

By 1891, when Some Strange Comers of Our Country appeared, Lummis already had traveled extensively in the Southwest and had written sensitively about its people and culture. The volume is subtitled The Wonderland of the Southwest, and Lummis included descriptions of the Grand Canyon, Montezuma Castle, Canyon de Chelly, Petrified Forest, and other unique places. 1n a brief article, "A Forest of Agate," he explained that the petrified trees revealed much about the history "uncounted millenniums" earlier, when the region had been inundated by the sea. The erosion that had exposed the fossil trees was a comparatively recent phenomenon, he wrote. A close observer of nature, Lummis recognized that Petrified Forest was an important link with the past. Whatever the geological implications, Lummis was more concerned to place the petrified trees within his book's theme of "strange corners," and he wrote enthusiastically about "this great natural curiosity-the huge Petrified Forest of Arizona." It was, he boasted, "an enchanted spot" where one seemed "to stand on the glass of a gigantic kaleidoscope, over whose sparkling surface the sun breaks in infinite rainbows." The rainbow forests were remarkable to look at-great curiosities, like many other novel places in the region. As was often the case among popular writers, scientific importance was overwhelmed by the tendency to describe natural phenomena as wonders, oddities, and curiosities.3l

Neither scientists nor popular writers had yet given educated Americans any precise reasons to preserve the petrified forests, beyond the simple plea to save the colorful deposits for future generations. Not many Americans in the late nineteenth century thought in terms of geologic time, and no one had fashioned any critical link between contemporary life and the continent's ancient landscape. While Americans might describe Petrified Forest as a natural wonder, clearly this reserve fell short of the monumental scenery at Yellowstone or Grand Canyon. The petrified trees, consequently, often were relegated to the status of curiosities that attracted tourists and perhaps businessmen who might find a market for the commodity.

By the last decade of the century, Petrified Forest was easily accessible. The little settlement at Adamana never developed beyond the few buildings clustered along the Santa Fe right-of-way, but it quickly became the most important gathering point for visitors to the petrified forests. Santa Fe Railroad officials arbitrarily named the place by combining the names of Adam and Anna Hanna to produce Adamana. For several years, Hanna had run stock in the area, but he recognized early the benefits of meeting tourists at the station and conducting them to his ranch, from which they could easily visit the forests.

Late in the summer of 1895, Hanna greeted a group of Californians at the station. Leading the contingent was Pasadena bookstore operator Adam Clark Vroman, who later would gain fame for his photographs of southwestern Indians. With him were Mrs. Thaddeus Lowe, Horatio Nelson Rust, and C. J. Crandall. Hanna loaded them into his lumber wagon, and he and a nephew guided them through the collections of petrified trees nearest the ranch. "The team was slow beyond measure," Vroman complained, "and the road nearly as smooth as no road at all. Simply a trail."32 He was equally disappointed when he found no standing trees but "simply broken pieces of petrified wood lying about." He recognized, too, the limits of black and white photography. "To capture the intensity and variety of colors in this wonderful freak of nature is difficult," he acknowledged; "the one thing lacking, Color, is so important." Nevertheless, Vroman took a number of pictures and could not resist lining up his friends on the agate bridge for the customary photograph. Jotted on the back of the picture is Vroman's telling comment: "Some heathen will lay a pound of dynamite on it some day, just to see it fall and thus removes [sic] the most interesting part of the forest." 33

Vroman may have been simply predicting the future, but his statement more likely was a comment on the destruction of the fossil logs. Vandals and souvenir hunters had carried off untold amounts of petrified wood already. Even more destructive were crews of men, some hired by eastern jewelers, who dynamited the logs in search of the quartz and amethyst crystals often found on the inside. Since the mid-l 88os, the semiprecious fossil wood had been the object of occasional business ventures. Because of its extreme hardness and myriad colors, petrified wood had the potential for numerous uses, particularly in decorating homes, as George Kunz had predicted. When cut and polished, it exhibited a lustrous finish that was nearly impossible to mar. Even smaller pieces, when carefully cut and polished, could be fashioned into cane and umbrella handles, paperweights, jewelry, and similar items.

The late nineteenth century was a time of sustained economic growth in the United States. The industrialization and urbanization of the East Coast and upper Midwest had its counterpart in the exploitation ofwestern resources from forests and grazing land to mineral deposits. Entrepreneurs in the West had little appreciation for scenery and were determined to develop resources, regardless of an area's designation as national park or forest reserve. The country's few national parks already bore the marks of visitors and developers. Fences, haphazard construction, and extensive grazing had marred the Yosemite Valley, and before Yosemite National Park was established in 1890 thousands of acres of pristine forest lands fell to private operators. At Yellowstone, game was slaughtered and geysers and craters defaced. As early as 1882, Yellowstone's historian Richard Bartlett has written, the park was "already under siege." Both parks eventually passed under temporary administration by the U.S. Army. Others were not so fortunate. Redwoods in Santa Clara and Santa Cruz Counties, California, as well as the East Bay, were cut during the gold rush years and used to build Oakland, Berkeley, and the towns in Santa Clara County. At Arizona's Grand Canyon, prospectors filed mining claims, and when Congress established Mount Rainier National Park at the end of the century, the legislators allowed mining and mineral exploration to continue. In short, exploitation of resources was common in the various federal reserves in the West. The deposits of petrified wood inspired the same kind of economic interest. Mineralized wood was potentially valuable, and optimistic businessmen understandably envisioned these deposits as the core of future wealth. 34

To take advantage of the seemingly endless supply of petrified wood in the region, a group of San Francisco businessmen organized the Chalcedony Manufacturing Company in 1884, filed several mining claims in the deposits of petrified wood, and within a short time shipped about fifteen hundred pounds back to San Francisco. Their crude lapidary equipment proved incapable of cutting and polishing the wood, and the partners soon became disillusioned. When William Adams Jr. offered to buyout their operation for two thousand dollars a year later, the Californians were happy to turn the enterprise over to him.35

The new owner, "Petrified Adams" to local residents, would never realize his dreams of wealth, although he reorganized his Jasperized Wood and Mineral Company several times in the 1880s. To secure a constant supply of petrified wood he hit upon the novel idea of filing placer claims, reasoning that these stone trees were, after all, mineralized. In all, his company tied up more than eighteen hundred acres that included extensive deposits of petrified logs. Still the operation did not prosper. 36

In the meantime, the U.S General Land Office became suspicious of Adams's activities, despite his pleas that his workers had caused little damage to the petrified trees and had removed nothing that would injure the value of the site. Still, Adams had shipped out some eighteen tons of petrified wood by the summer of 1888, and the General Land Office wanted his operations curtailed. Tom M. Bowers, an agent on the scene, advised that petrified logs be deSignated specifically as wood, not minerals, and therefore not subject to the Mining Law of 1872. Adams's claims therefore could be canceled or declared vacant. Concerned by this federal threat to his enterprise, Adams quickly secured a lease to operate on Santa Fe Railroad land37

Most of the petrified wood from this area was shipped to Sioux Falls, South Dakota, where the Drake Company had established a business to cut, polish, and market petrified wood. In addition to Col. James H. Drake. associates included the Arizonans Francis Hatch and Frederick Tritle. Drake spent years experimenting with various methods of cutting and polishing silicified wood before he ever succeeded. Even then, he later admitted to John Muir, the enterprise had not been a financial success. "I fancy that we threw into the waste heap material which represented $25.000 in expenditures," he complained. The major problem was not only the hardness of the petrified wood but the fact that it also was extremely brittle. After virtually days of careful, monotonous sawing, Drake explained, the pieces often cracked and then broke. By 1906. he simply had stopped working with the material.38

What success the company enjoyed had been limited to its exhibition and sales at the Chicago World's Fair. Drake displayed polished slabs of petrified wood both in the Arizona Building and in the Manufacturers' Building, and thousands of visitors admired the specimens. But even at that early date, it was evident that Arizona's petrified forests contained few logs that were sufficiently perfect for the production oflarge flawless slabs. Any large objects fashioned from petrified wood were destined to be costly luxuries. 39 At best. smaller segments might suffice for such items as cane handles and paperweights. The single exception remained the base for the Tiffany centerpiece that had been presented to Bartholdi.

Despite the dreams of wealth held by people like Adams and his partners, the cutting, polishing, and sale of petrified wood never proved profitable. The Jasperized Wood Company must have exercised a near monopoly on the supply of the commodity, but the business never amassed the wealth its owners anticipated. In the 1892 edition of Gems and Precious Stones of North America, George Frederick Kunz provided estimates of the value of silicified wood produced and sold in the United States. The total for 1883 was only $5,000; in 1884, $ 10,500; and in 1885, $6,500. The last years of the decade showed some improvement, particularly 1887, when $ 35 ,000 worth of silicified wood was sold as specimens and curiosities and another $ 1,000 worth sold for cutting into gems.40 A year later, though, the annual total was down to $ 16,500-well above the figure for the early 1880s but hardly enough to sustain businesses of any size. Moreover, Kunz's figures reflected national sales of petrified wood, not just the commodities produced in northeastern Arizona.

Because of the expense and difficulty of cutting and polishing petrified wood, Adams found the demand for his wood gradually tapering off. But theft and vandalism at the hands of visitors continued unabated, and a new threat emerged when a Chicago company made plans to erect a stamp mill to crush petrified wood for industrial abrasives. By then, Arizonans living in the vicinity of Chalcedony Park already were concerned about the depredations. Territorial Representative Will C. Barnes and several Holbrook residents took the initiative in a movement to preserve the area's scenic and scientific wonders. On February 1, 1895, Barnes introduced in the Eighteenth Territorial Legislature House Memorial NO.4, which called on the General Land Office to withdraw from settlement all public lands covered by the petrified forests until an investigation was undertaken to determine whether the sites deserved federal protection as a national park or reserve.4l

The threat posed by the abrasives company had repercussions far from Arizona. The firm had announced its intentions in the Albuquerque Democrat, and before long word had filtered back to the Interior Department in Washington. Secretary David R. Francis, alarmed that Armstrong Abrasives of Chicago was"appropriating the petrified forest and shipping it back to Chicago where it will be converted into grindstones and emerywheels," asked the GLO to dispatch an inspector to the site immediately. On December 15, he followed up with a proclamation formally withdrawing from settlement two townships containing deposits of petrified wood 42 By his quick action, Secretary Francis had satisfied the first part of the Arizona memorial-withdrawal of the land from settlement. A similar proclamation four years later doubled the amount of land closed to public entry. Such actions obviously were temporary expedients, but they were the only measures the federal government could employ to protect valuable sites at that time.

The memorial itself was critically important in the lengthy procedure that culminated eleven years later in a presidential proclamation that established Petrified Forest National Monument. It put Arizona's politicians squarely behind the effort to preserve the valuable deposits, and in the intervening years, scientists, local residents, bureaucrats, and political leaders laid the foundations for preserving the Petrified Forest. Though little would be done immediately to prevent thefts and vandalism, settlers were directed elsewhere, and the forests gained a temporary reprieve from commercial development.