4

SCIENTISTS AND THE PETRIFIED FOREST IN THE EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY

The hours go on neither long or short, glorious for imagination ... but tough for an old paleontological body nearing 70.

John Muir

When Edgar Hewett broadened the concept of national monuments to include scientific sites, he created a special niche for Petrified Forest. The new monument contained a few important ruins, but the extensive deposits of petrified wood shaped the reserve's essential identity. Its boundaries in 1906 enclosed only a small portion of the fossil-rich Chinle Formation that is exposed throughout much of the Plateau Province. Petrified Forest therefore shares in the geological history of an extensive ancient environment; and as scientists and naturalists found and described additional fossils, they revealed the unique character of this future national park.

Long before President Roosevelt had set aside Petrified Forest National Monument, scientists already were searching the terrain for fossils. The petrified logs were well known, of course, but they represented only the most obvious and spectacular features that had eroded out of the Chinle. In 1889, Frank Knowlton of the National Museum had described these giant fossil trees as Araucarioxylon arizonicum. Knowlton and John Wesley Powell both collected leaf fossils from the Chinle Formation in northern New Mexico in the late 1880s and early 1890s, and George F. Kunz published descriptions of the deposits in the area known as Chalcedony Park. These efforts represented only the beginning, for a wealth of plant and animal remains lay entombed in the colorful rocks of the Chinle.

Since early in the nineteenth century, geologists had known that sedimentary rock units could be identified by the distinctive fossils they contained. This discovery, known as the law of faunal succession, made possible the erection of a stratigraphic classification based on time relations rather than on rock types. As a result, scientists could define major sedimentary rock units and, by using their distinctive fossils, distinguish time counterparts at various localities-even on opposite sides of an ocean. Stratigraphie units, each representing a segment of the geologie time scale, became known as geologie systems-the now familiar names of Cambrian, Ordovician, Silurian, Devonian, Carboniferous (Mississippian and Pennsylvanian in North America), Permian, Triassic, Jurassic, Cretaceous, Tertiary, and Quaternary. The Triassic (or Trias), important for Petrified Forest, was introduced in 1834, based on observations in western Germany and in Italy. On this side of the Atlantic years later, scientists identified additional fossil remains in the Triassic. Their endeavors continue into the present.

Awed by the size and brilliant colors of the petrified trees, few early visitors bothered to look for vertebrate fossils, but at nearby locations in northern Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico scientists had found in the Chinle Formation enough bones to identify phytosaurs and Typothorax. 1 Both are thecodont reptiles, ancient ancestors of the dinosaurs that developed when the Triassic was still young; they gradually became extinct at the close of that geologic period.

At the very end of the century, Lester Frank Ward arrived at Petrified Forest and undertook an extensive survey of the terrain. Ward recommended that the federal government protect the place as a national park, but his work there extended well beyond justifying a new federal reserve. In his report, Ward referred conSistently to Arizona's petrified "forests," speCifically employing the plural to describe several distinct deposits in the area south of Adamana. He identified the now familiar Chalcedony Park as the principal location, noting that petrified logs there were literally countless and lay scattered on knolls, spurs, and buttes and in ravines and ditches. The ground everywhere seemed "studded with gems"-mostly broken fragments of all shapes, exhibiting all the colors of the rainbow. An additional forest, much smaller in extent, was situated north of Chalcedony Park, not far from the Puerco River. A third accumulation, which Ward simply called "middle forest," lay about two miles to the east.

These three forests, Ward wrote, were "geographically speaking, entirely out of place." He believed that the fossil trunks at Chalcedony Park had been washed out of their location atop a plateau that bounded the area and rose some seven hundred feet above it. Ward noted that, directly to the west, the plateau exhibited a series of petrified trunks, many of which had weathered out on the slope or rolled down to the valley below. Just below the summit, in a bed of coarse, gray sandstone, the geologist found a number of places where logs and branches of petrified wood were embedded. "This, then, is the true source of the fossil wood," he declared. 2

Ward's observations naturally raised questions about Möllhausen's earlier descriptions of the standing stumps in Black Forest in Lithodendron Wash. Ward could find no evidence in Chalcedony Park to confirm Möllhausen's contention that at least some trees had grown in place and been buried and petrified; nor did interviews with local residents provide any support for that view. "The only trunk I saw standing," he wrote, "was one that was inverted and had its roots in the air." There was no point in searching for standing stumps in Chalcedony Park and its neighbors, he asserted, since all of the logs in that area lay several hundred feet below their point of origin. The very abundance of these fossil trees ruled out their haVing grown in the same place. "Even if every tree had been preserved, there are places where it would have been impossible for them to stand as thickly as they now lie on the surface," he pointed out, "not to speak of the space that trees in a forest need to survive." The fossil logs not only were prostrate, but they lay in "little collections and huddles quite differently from what would be expected if they were precisely where they grew." 3

The great accumulations of silicified trunks resembled the collections of logs and debris in the eddies of modern river deltas, convincing Ward that the logs had floated into the area some time before being petrified. The coarse sand and gravel beds in which the fossils occurred were highly favorable for silicification, he added, and the crossbedding indicated the existence of rapid and changing currents. According to Ward, the beds containing the petrified wood had probably sunk, and finer deposits had ultimately buried them at the bottom of the sea that covered the region at one time in the Mesozoic era. There they remained until the entire country was raised some five to six thousand feet during the episodes of mountain building that created the Sierra Nevada and Rocky Mountain ranges.4

Ward was the first paleontologist to examine thoroughly the area around Chalcedony Park, and his report generally expanded on the observations of earlier scientists and naturalists. Ward's descriptions were detailed and accurate, proViding a reasoned, scientific basis for extending federal protection to the petrified forests. Perhaps most Significant, he established that the extensive collections of fossil trees were of scientific interest. They were not simple "curiosities" or "freaks of nature"; nor were they mere commodities suitable for decorative or even industrial purposes.

While in Arizona in the fall of 1899, Ward ventured well beyond Chalcedony Park and investigated much of the Little Colorado Valley. His discovery ofphytosaur bones at Tanner's Crossing, near the present Cameron, Arizona, quickened his interest, and he determined to return to the site later. In 1901 , accompanied by Barnum Brown of the American Museum of Natural History, Ward was back at the location-now known as "Ward's bone bed." Here the two men collected two new kinds of animals from the Chinle Formation-Metoposaurus fraasi, a giant amphibian; and Piacerias hesterus, a huge reptile known only by its humerus. The Piacerias, scientists later determined, was the first record in North America of mammal-like reptiles called dicynodonts. The boneyard proved over the years to be a valuable and productive site for paleontologists. In 1936, Ward and Brown returned to the site and excavated the largest known phytosaur skull, which measured four feet, eight inches in length. 5

Ward also searched doggedly for remains ofleaves but had only limited success. Some poorly preserved imprints were found in a sandstone bed near Tanner's Crossing, and Ward thought they were remnants of coniferous twigs and branches. He also found the remains of a small petrified cone northwest of the present park. Like most geologists, Ward was generally convinced that the petrified trees throughout that region had floated to their locations from some other site. In 1901, though, he and Barnum Brown discovered north of Cameron twenty stumps that apparently stood exactly where they had originally grown.6 The location was some distance from Petrified Forest, but it rested in the same geological formation and confirmed that some trees had been growing in that area when the Chinle Formation was deposited. Among the chips and blocks of wood surrounding the stumps, Ward found a large number of "fruit-like objects," which he thought to be resin or pitch. Several decades later, investigations by Lyman Daugherty disproved Ward's assertion; the "fruit-like objects" proved to be the remains of pecky-heart rot caused by a fungus that attacked Araucarioxylon arizonicum.7

Ward's research had taken him well beyond Petrified Forest, and his work indicated that the fossil trees now embraced by the national park are part of a much larger ancient environment. The extensive Chinle Formation yielded fossils that dated back more than 200 million years and provided a glimpse of the earth's early history. In their research, Ward and his associates added a few more components to the region's Triassic landscape, though the picture still was far from complete.

Those same rocks also yielded the secrets of the early human inhabitants who first lived among the scattered trunks of petrified logs. In 1901 , archaeologist Walter Hough of the National Museum guided members of the Museum-Gates Expedition through Petrified Forest. Like many of the early archaeological activities in the Southwest, the primary goal of this one was the simple collection of artifacts. But, in the course of their fieldwork, expedition members excavated portions of numerous sites (usually focusing On burial grounds), compiled ethnological information on the Hopi and myths of clan migrations from the south, and located and mapped some of the larger ruins in the area. Hough also provided a unique perspective on prehistoric human activity in the petrified forests. In an article for Harper's Monthly Magazine, "Ancient Peoples of the Petrified Forest of Arizona," he remarked on how the brightly colored fossil trees "expanded the fifth sense of wonder." But that was not all, for his research revealed that "a touch of human interest" was involved in the region's prehistory. Petrified Forest and the surrounding countryside had been home to tribes of ancient pueblo dwellers, he explained, people who "lived and loved, builded, fought, starved, and perhaps dined on one another." 8

Within the present park boundaries, Hough examined the Puerco Indian Ruin and the nearby petroglyphs as well as the Twin Buttes site. Milky Hollow, Canyon Butte, and Stone Axe ruins, all in the immediate vicinity, also were investigated. Canyon Butte proved particularly intriguing, for the site had no access to water whatsoever and bore no evidence of vegetation. Yet it yielded considerable pottery, shell beads, prayer sticks, and other objects. Hough described one of the structures as the "pueblo of the cannibals." Among the orderly burials, workers uncovered a heap of broken human bones, apparently the remains of three people. The shattered bones had been clean when placed in the ground, Hough wrote, and some clearly had been scorched by fire. A few bore the marks of whatever tools had been used to break them. "Without a doubt, this ossuary is the record of a cannibal feast," he commented. But since this was the only such find in the area, Hough described it as "probably anthropophagy from necessity." The same pueblo ruin yielded the skeleton of a priest, Hough believed, and a extensive collection of implements of that profession. These artifacts and the pottery found at the site suggested its connection with the Zuni.9

In all, his investigations in and around Petrified Forest convinced the archaeologist that four different "stocks" of Indians had lived there-a substantial number for a locality without permanent springs. He was certain that one of the groups was Hopi, possibly a clan on its northward migration to Tusayan. Another seemed to be related to the Zuni, although Hough was less certain about this group. The remainder he categorized as enigmas, people in a low state of advancement in comparison to the others. 10

Hough's work in Petrified Forest and its vicinity was part of the larger Museum-Gates Expedition, which undertook excavations and surveys from the White Mountains northward through Petrified Forest and on to the Hopi Mesas. In all, some fifty-five ruins were visited and eighteen sites excavated in a region roughly two hundred miles by seventy miles. A recent archaeologist describes these early endeavors as "pioneer regional archaeology" but cautions that such early surveys and excavations are not to be dismissed. People like Hough made astute observations, and the hypotheses advanced early in the century are today being tested and sometimes justified. 11 Hough was the first professional archaeologist to conduct major investigations in Petrified Forest and its immediate environs, and his work provided the first glimpse of the region's prehistoric inhabitants. In addition, he sought to describe them within the context of the prehistoric cultures of the Southwest. Modern archaeologists know that Petrified Forest rests in an area where several cultures mingled, and Hough's early observations anticipated these later findings.

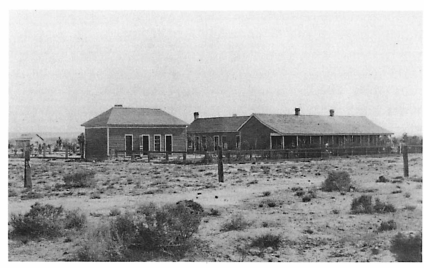

While Hough had made Holbrook the base for the Museum-Gates Expedition, other investigators preferred to operate out of tiny Adamana because of its proximity to the deposits of petrified wood. The Santa Fe Railroad also found it a convenient spot to deposit tourists, particularly after the Forest Hotel was constructed just before the turn of the century. Even then, Adamana consisted only of four buildings-the other three being a nondescript station, a coal bunker, and a water tower. The hotel, a ranch-style structure set back a short distance from the tracks, included a number of comfortable guest rooms, all of which opened onto a veranda that ran the length of the structure. ASanta Fe Railroad brochure published in 1912 assured travelers that they would be "nicely cared for." Board and room were a modest $2.50 per day, and the hotel could accommodate twenty guests. The dining room served thirty. Despite its remote location, the owners of the Forest Hotel offered travelers good food and clean rooms. Young Alice Cotton, visiting the petrified forests with her father in January of 1906, was impressed with its charming living room and comfortable guest quarters. 12

If its proprietor, Al Stevenson, never grew wealthy, he and his family apparently earned an adequate liVing. The owners maintained a garden that yielded radishes, green onions, and a few other vegetables. In the spring of 1906, the steady stream of guests at the Forest Hotel had given the Stevensons a taste of real prosperity, and they purchased a camera and made plans to seed a lawn. In the meantime, though, one guest admitted, "there are the usual tin cans and grubs much the same." 13

When the Cottons visited the establishment in January 1906, they were the only guests registered. Temperatures in northeastern Arizona often drop below freezing at that time of the year, and the desolate, windswept terrain along the Santa Fe line seldom induced passengers to abandon their warm coaches or Pullman cars to endure a frigid tour of Petrified Forest. But, for the Cottons, this was the last stop on an extended western tour. At dinner the first evening were the Stevensons, the local schoolteacher, a few employees, and a couple of young hoboes who were enjoying the Stevensons' hospitality. Seated next to Miss Cotton were a young woman and her father-a thin, bearded man who appeared to be about sixty years old. "His serious and scholarly countenance was lighted by a gay twinkle in his eyes," she still recalled years later. Throughout the meal, she tried to place him, finally realizing that her dinner companion was the writer and naturalist John Muir. 14

The Forest Hotel, gateway to Petrified Forest from the late nineteenth century until the 1930S (Photograph from the Willard Drake collection, courtesy of the Coconino National Forest)

Muir undoubtedly entertained the small group at the hotel. A natural storyteller, he loved to talk, and his Scottish brogue enhanced his tales. He explained that Cosmopolitan magazine had engaged him to do a series of articles on the petrified forests. 15 In reality, Muir's visit to Petrified Forest had comparatively little to do with writing; rather, it was the poor health of his daughter Helen that brought Muir to Arizona in 1905. Muir's wife, Louie, had died suddenly that summer, and shortly afterward he moved to Adamana with Helen and her older sister Wanda. Helen's lingering pneumonia was a source of constant worry for Muir, and he hoped that the dry desert air might restore her health. At Adamana the trio became "permanent guests" at Al Stevenson's establishment. Actually, they only took their meals at the hotel, since Muir had arranged for a comfortable, two-room cabin with a fireplace. On many occasions, they preferred to sleep in a tent. 16

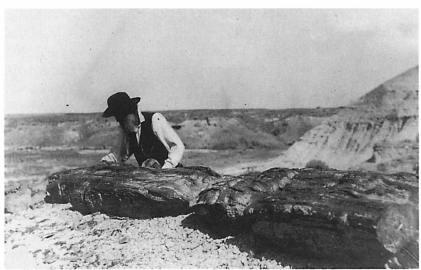

Helen responded quickly to the desert climate, and Muir was delighted with her improvement. The sojourn at Adamana also helped him to recover, for the trying events of the 1905 summer had left him "stunned and decidedly tired," he told a friend. 17 But for some time Muir lacked the concentration and discipline necessary to write. Instead, he found a new avocation in exploring the nearby deposits of petrified wood. To Robert Underwood Johnson of Century magazine he wrote enthusiastically about "a half dozen or more thousand acres ... strewn thickly with huge agate trunks millions of years old." Johnson hoped that Muir might eventually contribute an article for Century, and he often gently prodded the naturalist to write. But Muir's responses typically began with allusions to his inability to concentrate, followed by exuberant descriptions of the petrified logs. 18 Clearly, study of the fossil trees was now the focus of Muir's intellectual interests, but that was no guarantee of an article or essay.

As a student at the University of Wisconsin in the early 1860s, Muir had enrolled in geology courses taught by Ezra Slocum Carr, a protege of Louis Agassiz, and he never lost interest in the subject. He was also a precise observer of nature, and earlier, in Yosemite, he had ascertained the role of glaciers in shaping the steep canyon walls and cliffs of that park. Northern Arizona presented a markedly different environment, but the petrified trees near Adamana captured his imagination immediately. He identified Araucaria, Sigillaria, Lipidodendrons, and tree ferns that he believed "flourished gloriously millions of years ago in the bogs and woods of the Carboniferous period." By early in 1906, Muir's excavations among the deposits near Adamana had improved his spirits considerably. To a friend he wrote that "this hard work and hard enjoyment I find good for all sorrow and care," and to another he announced that "hard work in the petrified forests hereabouts has brought back something of the old free life with Mother Nature." 19

John Muir at Petrified Forest, 1906 (Photograph from the Helen Muir Collection, courtesy of Petrified Forest National Park)

Muir was an enthusiastic geologist, but he was not particularly well grounded in the discipline. He correctly identified Araucaria and Calamites, but other observations were wrong, particularly his placing of the fossil forests in the Carboniferous period (360 million to 250 million years ago) rather than the Triassic. Once convinced that the deposits dated back to the much older Carboniferous, he unavoidably made mistakes in his identification of some fossils. Muir placed nearly all his faith in experiencing and carefully observing nature and consequently deprecated the value of books. They were, he once remarked, "at best signal smokes to call attention." But from time to time on his visits to the family home at Martinez, California, Muir continued on to Berkeley to consult sources in the University of California library. His sketchbooks for 1905 and 1906 contain numerous pencil drawings of Sigillaria and Lipidodendron fossils, all of them apparently copied from standard texts of the period. Presumably, Muir used the sketches made at Berkeley to identify the actual fossils he found near Adamana. In his enthusiasm, he named those deposits the "Sigillaria Grove" and on a rough map he located them about six miles north of Adamana. 20

Neither Sigillaria nor Lipidodendron exist in Arizona's petrified forests, which date back only to the Triassic-information that was well established by the early twentieth century and easily accessible as well. Judging by Muir's correspondence, notebooks, and sketchbooks, he did not consult any of the material relating to exploration of the region, nor was he aware of descriptions and reports by such scientists as Marcou, Knowlton, and Ward. Not knowing the Triassic origins of the area and unaware of recent scientific literature, he may have mistaken two other fossil trees, Schilderia adamanica and Woodworthia arizonica, for Sigillaria. Neither of those two had been described back then, and surface markings might have led Muir to identify Woodworthia as Sigillaria. A second possibility remains. Fungus found on some Araucaria fossils might have convinced him that they were Lipidodendron. The fungus had not yet been identified either, which helps to explain Muir's erroneous descriptions of it. 21

In his wanderings about the area, Muir came across extensive deposits of petrified logs about six miles southeast of Adamana. He named the new site Blue Forest (now Blue Mesa), a name prompted by the blue-gray tint of the terrain. Between this new find and the Sigillaria Grove, Muir kept busy excavating among these stone trees, occasionally interrupting his work to travel back to his California home and, when possible, to Berkeley. By the spring of 1906, he was convinced that few scientists knew more about the "carboniferous forests" than did he and his daughters, and he was confident that they could "make a grand picture of those which flourished about the hills and dales and grazing lands." From Berkeley, he instructed Helen and Wanda to "gather up everything old and queer and see if I can't name them when I get back later with Greek and Dog-Latin." 22

Muir published very little about his findings at Petrified Forest. On one of his trips back to California by train, he talked briefly to a correspondent from The Worlds Work, lightheartedly discussing the novelty of the stone trees. Although the Santa Fe Railroad had advertised stopovers at Adamana and the Petrified Forest for years, Muir pointed out, "those fellows had waited all that time for me to come down there and find three more forests that not even the people in that country knew about-and one of them is the biggest one there." 23 Santa Fe officials eventually heard about the newly discovered Blue Forest and Sigillaria Grove and included a description of the sites in their advertising.24

Muir's digging and collecting at Petrified Forest coincided with Congressman Lacey's endeavors to establish Petrified Forest National Park. Muir knew about the 1906 park bill and naturally hoped that the legislation would pass, but he did nothing to help the measure along.25 Lacey relied extensively on Lester Frank Ward's recommendations, among those of several others, but he never called on Muir-the country's most widely known naturalist and proponent of national parks, not to mention something of an expert on the very petrified forests that Lacey hoped to preserve. By 1906, when Lacey introduced his fourth bill to establish Petrified Forest National Park, the testimony from "John of the Mountains" would have strengthened his arguments, not to mention the publiCity that Muir and such colleagues as Robert Underwood Johnson might have stimulated.26

Although Lacey ignored Muir, the Interior Department looked to him for advice concerning the area's suitability as a national park. In particular, the General Land Office wanted his recommendations about which deposits of petrified wood ought to be included. Further, because no current, official map of deposits of petrified wood existed, Washington needed from Muir a sketch of the area. Muir was glad to comply and recommended inclusion of the well-known First, Second, and Third Forests, along with his own recently discovered Blue Forest. These, he felt, would be most attractive to tourists because of the profusion of colors and the inherent beauty of the stone trees. He also recommended the inclusion of the Sigillaria Grove, which students of geology would find important. In that area, he noted, some of the stumps remained rooted where they had grown. Lacey's bill of 1906, of course, did not include these Sigillaria Grove. Although Muir favored a larger reserve (about three and one-half townships), he suggested that those deposits might initially be omitted to facilitate passage of the bill. The critical task was to secure the national park designation. Increasing the new reserve's size would be "a comparatively easy matter after it is better known and appreciated," he advised the GLO 27

With that advice, Muir was content to return to his Sigillaria Grove, leaving the preservation of the petrified trees in the hands of Congress and President Roosevelt. The summer of 1906 was the family's last one at Adamana. Helen had recovered completely, Wanda was making wedding plans, and Muir had been thoroughly rejuvenated by his lengthy excursions in "God's Auld Lang Syne," as he described Petrified Forest to a friend. For much of a year, he had worked in the deposits near Adamana, and he acknowledged that his" only great gain from these troubled times is the views I've gained from these grand forests of the world which flourished uncounted millions of years ago." 28 But for all his digging and research, Muir had not written so much as a page for publication. "How does your pen work these days?" Robert Underwood Johnson inquired in June 1906, adding a plea that Muir write his long-delayed piece for the Century. 29

The Muirs left the Forest Hotel in August 1906 and returned to the family home in Martinez. Muir eventually made a halfhearted commitment to begin writing a piece for Robert Underwood Johnson, but he was much more interested in identifying the fossils he had retrieved from Petrified Forest. He lost no time in contacting paleontologist John C. Merriam of the University of California, who examined the small collection of vertebrate fossils and identified them as the remains of phytosaurs. 30 Muir eventually presented the fossils to the university, and they became part of its paleontology collection.

The article for Century magazine never appeared, nor did Muir ever write anything on Petrified Forest. For all his fond references to "God's Auld Lang Syne," he never placed his experiences in Petrified Forest within the framework of his other writings on nature. No "grand picture" of that ancient environment ever emerged. The omission is unfortunate, for Muir had long been convinced of the interdependence in nature. "When we try to pick out anything by itself," he had written earlier, "we find it hitched to everything else in the universe." To what were these fossil trees hitched? And where did they fit in the scheme of nature? Muir's serious excavation and his determined study of fossils suggests that he was anxious to learn about the origins of Petrified Forest. And after months of intensive work, he obviously had moved toward some conclusions, as implied by his comment to Johnson that his .. great gain" in 1905 and 1906 had been "the views I've gained of these first grand forests of the world." Whatever perceptions Muir had developed, he kept them to himself, leaving others to puzzle out the importance of these ancient forests and the creatures that dwelled within them.

For Muir, the year at Petrified Forest had been a time of rest and renewal following the death of his wife. His daughter's subsequent recovery in the high desert air naturally relieved him, too. And there can be no doubt about his enthusiasm for excavating and studying the area's fossil trees. The year of relatively intense fieldwork, combined with the excitement of making seemingly new discoveries, had contributed to his recovery and provided him with a sense of accomplishment. It had been a needed respite-a time to regain strength and nurture his daughters. 31

Muir contributed only in a small way to the preservation of Petrified Forest. And he did not broaden our understanding of geology or paleontology, because many of the fossils he discovered were identified incorrectly. For a while thereafter, both the Santa Fe Railroad and local newspapers touted his discoveries of the Sigillaria Grove and Blue Forest. But eventually they dropped references to the former. The nature of Muir's contribution to science at Petrified Forest is difficult to assess. He in fact discovered the unique Blue Forest, but beyond that the renowned naturalist made no seminal discoveries, despite the expenditure of considerable effort.

Muir observed Petrified Forest as a naturalist and scientist, seeking to place the fossil trees in the context of the earth's history. He recognized them as ancient forests (too ancient, since he identified them as Carboniferous) , and he understood that they had grown in a landscape obviously different from that of the twentieth century. Like glaCial valleys, geysers, and eroded canyons, Muir recognized Petrified Forest as a geological creation that helped define America's cultural identity and also captured the interest of tourists.32 By the early twentieth century, Americans were learning more about the West-its landscape, inhabitants, and climate. The remains of these ancient forests suggested that the region's past was more extensive, and perhaps more Significant, than people had realized.

For the next decade, little scientific activity occurred preCisely within the new monument, but scientists were busy at a number of places in the Chinle Formation of the Plateau Province. S. W. Williston and his assistant, Paul Phillips of the University of Chicago, gathered a small collection, including phytosaur bones, in the Zuni Mountains in 1912. The party returned a year later and discovered a complete phytosaur skull. A few years later, Maurice G. Mehl and his student G. M. Schwarz of the University of Wisconsin, worked both at Cameron in the Little Colorado Valley and at the Zuni uplift, where additional phytosaur remains were unearthed. 33

From time to time, even local residents around Petrified Forest uncovered remains of these crocodile-like animals. Robert R. Alton, proprietor of a small store near Adamana, found a portion of a phytosaur skull just a few miles south of the town. Eventually, that fossil ended up in the geology collection of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. Then, in 1919 at Muir's Blue Forest, Ynez Mexia made an important discovery of vertebrate fossils, including the first phytosaur skull from Petrified Forest, which she sent on to the University of California. 34

Mexia's find also caught the attention of Berkeley's Annie Alexander, who was familiar with Muir's fossil collection. With her friend Louise Kellogg, she retraced Mexia's steps and made important discoveries of phytosaurs and Placerias. The two women not only excavated beds near Blue Forest but also discovered a rich new site at Devil's Playground above Lithodendron Wash. Neither Alexander nor Kellogg was a scientist, but Annie Alexander, in particular, had a long-standing interest in paleontology that had begun when she and friends attended lectures by John C. Merriam, then an assistant professor at the University of California. Not long after she and Kellogg had found the fossils in Petrified Forest, she established the Museum of Paleontology at the university and later provided it with an endowment for scholarships.35 The excavations by Alexander and Kellogg marked the beginning of intensive work by the University of California at Petrified Forest.

So promising were the discoveries by Alexander and Kellogg that Charles L. Camp, a new Columbia University Ph.D., traveled by train to meet the two women at Adamana. Fieldwork at the sites began in earnest that summer and yielded some two thousand pounds of fossils, which were shipped back to Berkeley. The intense summer fieldwork at Petrified Forest largely shaped Camp's early career. His interest in the Chinle Formation and its fossil vertebrates drew him back to northeastern Arizona and northern New Mexico again and again. Two years later he discovered a rich zone of fossil deposits in the Blue Forest area. The site, named "crocodile hill," yielded numerous skulls of phytosaurs and metoposaurs. During that same season, Camp's field assistant found a new fossil location at Billings Gap, about four miles to the southeast. In 1927 Camp spent a week at Petrified Forest, concentrating his work at Devil's Playground. He met a local resident named Dick Grigsby during his stay there, and the latter led him to a concentration of fossils in a tributary of Lithodendron Wash. "Almost every specimen is a phytosaur skull," Camp wrote. "I saw six of them including the one already collected by Grigsby." This discovery was particularly significant because the skulls exhibited a series of growth stages and sexual differences in a single phytosaur species.36

Camp excavated a number of sites in New Mexico and Arizona in the 1930s. He made his last visit to the Chinle Formation in northern Arizona in 1934, when he and Samuel Welles continued excavation at the" Placerias Quarry" near St. Johns. Over the years this single site yielded some 815 skull bones that carne from at least thirty-nine of the animals, along with the remains of phytosaurs and other ancient creatures. Camp's work was important beyond the sheer wealth of fossil amphibians and reptiles that he and his associates collected. His real success, as his colleague Samuel Welles pointed out years later, was his ability to stimulate his students to undertake investigations on other horizons of the extensive Colorado Plateau.37

In a broader context, Camp, like Annie Alexander and John Muir, exhibited that sense of curiosity that Lester Frank Ward had eloquently described decades earlier. The fossils they discovered went back to Berkeley, and these early naturalists and scientists contributed to the expanding discipline of geology. Gradually, such research shaped the identity of Petrified Forest National Monument. The deposits of petrified logs would always attract visitors, but by the first decades of the twentieth century, scientists had revealed that the primeval swamps that buried these great logs also were horne to phytosaurs, Placerias, and a variety of other creatures-residents of an ancient wilderness that awaited further exploration.

Phytosaurs are perhaps the best representatives of the Triassic faunas of the region. They were thecodont reptiles from which later dinosaurs evolved, but they differed from bipedal members of the order that walked on powerful, birdlike hind legs (such as Hesperosuchus). More advanced thecodonts, phytosaurs became increasingly larger until some of them grew to almost giant stature. The bipedal pose was left behind, and phytosaurs developed into long quadrupedal reptiles inhabiting the shores of streams and lakes. As they evolved, they retained the armor plates characteristic of primitive reptiles. Some grew into heavily armored animals-what one expert calls "veritable Triassic tanks." 38

Phytosaurs seemingly abounded in and around Petrified Forest, and their presence suggests that the ancient ecosystem depended on the existence of numerous streams and lakes-the habitat of these aggressive animals that fed on a variety of smaller creatures. Similarly, the residence there of the large herbivore Placerias indicates considerable vegetation to sustain the foragers. Such discoveries incrementally added to the overall understanding of the Triassic period in the earth's history. The evidence still was sketchy, but scientists later would identify this as a crucial time of transition, when the planet's ancient life was giving way to evolutionary pressures exerted by new and vigorous plants and animals that would dominate the earth for the next 100 million years. 39 Scientists in the first third of the century had found at the reserve an immense laboratory that promised to expand our understanding of the Triassic. And this suggested, too, that in the future Petrified Forest would playa broader interpretive role among the country's parks and monuments.

None of these discoveries had fully registered with Stephen Mather and Horace Albright, or with any other officials at the National Park Service or Interior Department. Although the Antiquities Act specifically identified sites of scientific interest as worthy of monument status, the measure did not commit the federal government to supporting scientific research or establishing educational programs. Mather and Albright probably were not fully aware of the extent and Significance ofresearch under way at Petrified Forest. Local administration there was in the hands of volunteer custodians, whose correspondence with the Interior Department tended to be infrequent and often dwelled only on matters of theft and damage.

By the 1920s, Petrified Forest was the destination of growing numbers of travelers, thanks to the popularity of the automobile. These new visitors, far surpassing the numbers that had come aboard the Santa Fe before World War I, were a cause for concern at Petrified Forest. Not only did they secrete away uncounted tons of souvenirs over the years, but they also defaced and vandalized natural features. Consequently, park policy focused narrowly on protecting the petrified logs, while little time or money was set aside for educational endeavors and displays to exhibit the discoveries that researchers made. Decades later, when expanded ranger forces and modern facilities helped monitor visitors, the Park Service could turn its attention fully to science and interpretive displays at Petrified Forest.