6

THE IDEAL NATIONAL MONUMENT

There are neither snow-capped mountains nor abysmal canyons in the monument, yet it is by no means devoid of scenic value on a smaller scale.

NPS landscape architect C. E. Peterson, 1930

M. R. Tillotson's lengthy report prompted the Park Service to make a crucial decision about Petrified Forest. With the number of visitors approaching 100,000 annually, the agency no longer could face the embarrassment of the reserve's dilapidated facilities, nor could it rely any longer on unprofessional, short-term custodians. In the future, Petrified Forest's administration would reflect the Park Service's professional gUidelines, and its buildings and roads would also meet standards. Attaining these goals meant a major change for the reserve, and in veteran ranger White Mountain Smith, Albright selected an individual capable of shepherding Petrified Forest through a major transition. Between 1929 and 1940, when Smith departed, the reserve was virtually transformed. Not only were facilities improved, thanks to the money and labor provided by Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal programs; but the monument itself nearly doubled in size with the acquisition of the scenic Painted Desert. By the end of the 1930s, Park Service promotions acknowledged the changes and often described Petrified Forest as the country's "ideal national monument. "

White Mountain Smith was a Connecticut Yankee, but he had lived in the West for years and for much of that time had been associated with the National Park Service. Prior to his serving as chief ranger at Grand Canyon he had worked as a government scout at Yellowstone, his career there in the 1920s overlapping with a portion of Albright's superintendency. In fact, the Park Service chief personally chose Smith as Petrified Forest's custodian in 1929, intervening in a decision that typically had been left to Frank Pinkley.

If the appointment represented a promotion for Smith, his new domain-remote, neglected, and decidedly shabby-was an unquestionable challenge. Clearly it was not in the same class as the Grand Canyon or Yellowstone. Living quarters were, as Tillotson had described them, dilapidated shacks, shabby enough to have sent an earlier custodian and his wife scurrying for another job. Fortunately, by 1929 a modern three-room residence was under construction near Agate Bridge; it was the only truly habitable building evident that summer when Smith looked over the reserve. Overshadowing all other problems was the issue of private land within the monument. The checkerboard pattern of federal and private holdings dated back to the original railroad land grants in the region, but now those inholdings precluded all development. The north-south road across Petrified Forest was really more of a trail than a highway, but the Interior Department could not authorize expenditures to improve a road that crossed private holdings every other mile. For part of the year, Smith complained, this "trail road" was nearly impassable. l Beyond that, lack of a bridge across the Puerco River disrupted traffic between U.S. 66 and the monument-a particular frustration in the summer travel months, when Arizona's monsoon-like rains turned the Puerco and nearby Dry Creek into torrents.

The only solution, Albright realized, was elimination of the privately owned land. 2 With the support of the Park Service and Interior Department, Congress on May 14, 1930, passed a land exchange act authorizing the federal government to obtain title to privately owned land within Petrified Forest National Monument through exchanges for similar public land of equal value in Apache County, Arizona. Smith had held preliminary talks with a representative of the Arizona and New Mexico Land Company even before the measure passed, and the two soon worked out an agreement that allowed the company to select five acres of public domain for each one of its acres within Petrified Forest. 3

As the Santa Fe relinquished its holdings in Petrified Forest, the federal government was also able to expand the monument by 11,010 acres and return some of the land that President Taft had retracted in 1911 . President Herbert Hoover took care of the matter by proclamation in November 1930, adding Muir's Blue Forest and the Puerco Indian ruins and nearby petroglyphs. In addition to these sites, the small acquisition contained the only practical site for a bridge across the Puerco.4

In the meantime, the Park Service made plans to eliminate the unSightly shacks and provide new rangers' quarters. Dick Grigsby held the only concession in the monument, and his store was one of the few presentable buildings within its boundaries. Therefore the Park Service allowed him to build several housekeeping cabins and even provided an architect to draw up plans. To the blueprints the Park Service architect appended his opinion that Petrified Forest "will never become a vacation retreat such as the national parks are." 5 The remark identified a critical issue at Petrified Forest. Though there was no doubt about the importance of its geological and archaeological sites, the monument lacked the grand scenery that Park Service officials and tourists alike associated with national parks. Given such perceptions, White Mountain Smith's national monument seemed unlikely ever to become anything more.

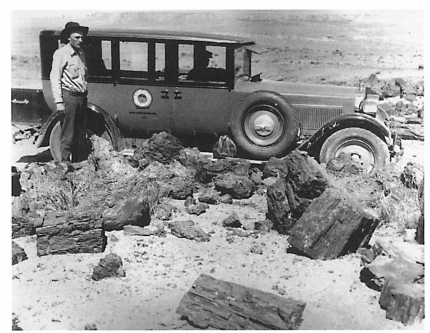

At the same time that automobiles were bringing more visitors to Petrified Forest, the Santa Fe Railroad and the Fred Harvey Company initiated their Southwestern "Indian Detours." The Santa Fe had advertised stopovers at various points of interest for years, and the new detours expanded on these original side trips. Hunter Clarkson of the Harvey Company in 1925 designed the excursions, which embarked initially from Las Vegas and Albuquerque, New Mexico, to visit Santa Fe and various pueblos. When announcing the new tours on August 20, 1925. Clarkson aptly described them as "detours." The company inaugurated its Petrified Forest Detour on June 1, 1930, when a tan-and-brown Packard "Harveycar" delivered a Single California tourist to Petrified Forest. For Smith, the arrival of this lone visitor marked the beginning of a new era for the monument. The Californian was the first of thousands, Smith predicted optimistically, who would take advantage of the Santa Fe- Fred Harvey experiment to visit the forest. 6

The detours treated travelers to an exceptional view of the Painted Desert, along with a tour of the Petrified Forest and a lecture at the museum. Clarkson's seven-passenger, open touring cars featured leather upholstery, two jump seats, and a folding rear windshield. On the radiator of each, "Packard Harveycar" was spelled out in a special script. The larger sixteen- and twenty-six-passenger coaches had similar leather upholstery, swiveling seats, and large glass windows to enhance the travelers' view. Along the way through Petrified Forest, visitors enjoyed basket lunches, and on some tours they could anticipate dinner at Harvey's La Posada in Winslow or another of the Harvey inns.7 During the 1930 travel season, despite the impact of the stock market crash and the early effects of the Great Depression, visitors arrived at Petrified Forest in record numbers. In September, Smith recorded 12,394 visitors, about 1,200 of whom took advantage of the detour service. The year's total reached 105,433. 8

Tourists who reached Petrified Forest via U.S. 66 invariably were impressed by the views of the Painted Desert, which stretches off to the northwest of the monument and extends eventually some 150 miles along the Little Colorado River toward its junction with the Colorado. Lithodendron Wash crosses it, and the Black Forest rests on its floor. The desert varies in width from about fifteen to forty miles, and its eastern part exhibits a particularly striking example of badlands terrain. Its southern fringes are only a few miles north of Petrified Forest, and this colorful stretch of land was a natural scenic complement to the monument. Its subtle shades of reds to pinks dictated its name, a designation that recalled the Desierto Pintado of the sixteenth-century Spanish explorers.

In 1924 Herbert D. Lore built a trading post and hotel, appropriately called the Painted Desert Inn, on a bluff that offered a panoramic view of the colorful desert landscape below. By then the automobile's popularity already was undermining rail-oriented institutions like the Adamana Hotel. Whereas the Nelsons had resisted the obvious trend toward automobile tourism in the 1920s, Lore astutely took advantage of it. The inn, labeled the "stone-tree house" in brochures, was a more substantial operation that the roadside gas stations and other businesses strung out along the highway. But like the smaller operators, Lore and his wife recognized that money could be made from Route 66 travelers. To guarantee that no one missed the inn, Lore constructed a large, red, electrically lighted sign at the main entrance road to his establishment. The place was an oasis for travelers who endured the heat, dust, and isolation along the route, and it served as an outlet for Navajo and Hopi arts and crafts.9

By the 1930s, Lore was willing to dispose of his holdings, and he sounded out the General Land Office about exchanging Painted Desert acreage for public domain elsewhere. He also wanted to sell the inn and its improvements to the government. At the same time, the Santa Fe Railroad offered its land in the vicinity for exchange. The two proposals raised the possibility of substantially expanding the monument by adding the scenic desert terrain.

White Mountain Smith initially was not an active proponent of the acquisition, although he had long admired the Painted Desert's vivid colors and its quiet beauty. He was convinced that it would attract enough visitors to justify its acquisition, but he also had a pragmatic reason to support federal control over the area: Lore's Painted Desert Inn actually competed with Petrified Forest. "When one has paid admission to Lore's area and carried away free wood as a souvenir," Smith explained to Assistant Director Conrad Wirth, "that person does not care to visit Petrified Forest National Monument." 10 Incorporating the inn and surrounding desert would end this competition and also increase the number of visitors to Petrified Forest. That should translate into more funding to operate the monument, Smith realized.

By the summer of 1931 , support for incorporating the Painted Desert into Petrified Forest National Monument was virtually unanimous. The principal landowners-Lore, the Santa Fe, and the state of Arizona-were ready to negotiate exchanges, indicating that the Park Service could acquire the land (but not Lore's improvements) at little cost. From Washington, Assistant Director Conrad Wirth added momentum to the cause when he stated that the addition of the Painted Desert to other scenic areas in Petrified Forest would qualify the expanded reserve for national park status. 11 As a veteran official of the Park Service, Wirth knew that neither his agency nor Congress would be likely to support national park designation for any reserve that could not boast at least some extent of spectacular landscape.

The scenery of the Painted Desert was clearly a crucial argument in favor of expanding Petrified Forest, but there was also the issue of protecting the Black Forest. With thousands of visitors stopping at the Painted Desert every year, the potential for theft and damage was immense. Smith knew that nearby residents had carted off substantial amounts of petrified wood; he had seen it for sale at the shacks they constructed along Route 66. 12

Roger Toll, superintendent at Yellowstone and a frequent advisor to Albright on park matters, also supported the addition. He verified that the Painted Desert had little land available for grazing or commercial development. Its striking scenery constituted its only real value. 13 He also identified the importance of the Painted Desert Inn as a symbol for the expanded monument. The inn rests on a peninsula that projects into the desert and commands an incomparable view of the terrain. It was, Toll pointed out, comparable to Grand Canyon's El Tovar Hotel and "the central key to the situation." 14

By the end of the summer, Park Service officials had worked out land exchanges, but the purchase price of the inn and Lore's other improvements still had not been negotiated. The addition of the Painted Desert needed only the director's formal approval and the requisite proclamation from the preSident. Albright had maintained a good working relationship with President Hoover that dated back to his Yellowstone superintendency, and Hoover generally had favored the Park Service during his administration. He continued that relationship on September 23, 1932, when he Signed a proclamation that added the Painted Desert to Petrified Forest National Monument. In extending federal control over 53 ,300 acres of the southern and eastern parts of the Painted Desert, Hoover relied on the 1906 Antiquities Act that Theodore Roosevelt had invoked to establish the monument. Smith's domain now embraced 90,218 acres, adding to the original Petrified Forest the scenic desert terrain, the Black Forest in Lithodendron Wash, and a narrow neck ofland connecting the two parts. 15 U.S. 66 now virtually bisected the expanded monument, almost equidistant from the original Petrified Forest National Monument and the newly acquired Painted Desert.

Smith's monument was now more than twice its size when he had arrived two years earlier, and it promised a future more complex and varied than otherwise could have been anticipated. The expansion also marked a degree of maturity for Petrified Forest, in that the months preceding Hoover's proclamation were filled with important internal accomplishments. Congressional appropriations provided for construction in I 932 of a modern highway across the monument, including a bridge at the Puerco. To dedicate the structure, Horace Albright journeyed to Petrified Forest in July and joined Smith, Pinkley, Tillotson, and Arizona civic leaders for the ceremony. He also used the occasion to announce Smith's promotion to superintendent. With that, Petrified Forest became an independent reserve and was no longer subject to Frank Pinkley's direction from Casa Grande.

Pinkley had always emphasized the importance of educational exhibits and programs at the monuments, and in the spring of 1932 had arranged for Park Service naturalist R. W. Rose and field naturalist Dr. C. P. Russell to construct and arrange displays for Petrified Forest's new museum. The two assembled collections of petrified wood in glass cases and arranged other displays. The facility also acquired the skull of a phytosaur and that of an early amphibian, which the naturalists arranged for viewing by visitors. Another room was set aside for display panels that employed diagrams and sketches to explain the process of fossilization, the variations of colors in petrified wood, the formation ofcrystals, and similar topics. Russell added drawings of the Triassic landscape, portraying the lush semitropical terrain. 16

"Petrified Bill" Nelson had long since departed, of course, and gone was his shabby little specimen room with its stereopticon and magic lantern shows. But the emphasis on public displays in the new museum-though now more sophisticated and elaborate-continued a precedent that Nelson had set in the 1920s. The Park Service finally had developed an interpretive program that defined, albeit briefly, the significance of the reserve and attempted to convey the message to tourists.

The expansion of Petrified Forest, the substantial construction projects, and Smith's elevation to the position of superintendent all took place against the backdrop of the Great Depression. As the number of visitors slowly declined, personnel at the monument were reminded that the country was caught up in a severe economic crisis. The monument remained popular with motorists, although the number of visitors tapered off in 1932. Harveycar arrivals declined, too, and by September, Clarkson had abandoned the Petrified Forest Detour. 17

The dwindling number of tourists at the monument was symptomatic of the conditions in northeastern Arizona in the early years of the depression. Even in prosperous times the region offered few good jobs, and residents scrambled to earn a living. Many of them looked to Route 66, where paving was under way from 1930 to 1937. People built service stations, tourist courts, modest hotels, and camping facilities-anything that might attract passing motorists. In the Southwest, such small-time operators capitalized on local curiosities, and petrified wood was often an item of commerce. The ubiquitous "trading posts" and "Indian villages" that still are evident along Interstate Highway 40, the successor to Route 66, testify to the enduring trade in local crafts and curiosities. 18

In the fall of 1932 Smith constructed a checking station at the point where the Painted Desert rim road connected with U.S. 66. Cross-country travelers could easily leave the highway and follow this road along the Painted Desert to the old inn, some six miles to the northwest. 19 He expected the new acquisition to attract additional tourists, but neither he, nor Pinkley, nor Albright had given much thought to the impact of the expanded national monument on local residents, particularly the small operators along the highway near Petrified Forest. The Park Service presumed that the expanded reserve would stimulate the local economy somewhat. After all, more tourists should translate into a demand for more goods and services from businesses in St. Johns, Springerville, Adamana, Holbrook, and Winslow. But local resentment exploded in mid- 1933, when Julia Miller, owner of an establishment on U.S. 66 called the Lion Farm, complained to Interior Secretary Harold Ickes and Park Service Director Arno B. Cammerer.20 Smith's checking station and Painted Desert road, she charged, were ruining local businesses in the vicinity. Miller's complaints were accompanied by a petition signed by Sixty-three residents, who demanded Smith's removal or transfer. 21

Smith's rangers at the checking station in fact sent motorists along the desert rim road and on south to Petrified Forest, if they so desired, the superintendent maintained. The practice, of course, had the effect of inflating the number of visitors at his monument. The superintendent knew about Julia Miller and her Lion Farm and made no effort to disguise his loathing for both the woman and her enterprise. Park rangers ignored the Lion Farm, which, according to Smith, "would offend the sensibilities of any refined person." Miller kept a variety of animals in coops and cages, feeding them horse meat from animals killed on the range. "Sometimes the stench was overpowering," Smith complained. When he visited the place on August 2, Miller had on display an antelope fawn, two eagles, a bobcat, a fox, a mountain lion, a dog and a cat, and a couple of kittens. As far as Smith was concerned, the Lion Farm was "an unsightly, unsanitary place." Secretary Ickes shared Smith's disdain. Though he had never visited the establishment, he told Cammerer, "I have passed it on a number of occasions and I have felt it to be a blot on the scenery." Ickes understandably supported his superintendent at Petrified Forest, noting that he could find nothing in Smith's report that might be termed discrimination against Miller or her neighbors 22

The Miller affair might have ended at that point had it not been for the petition Signed by local residents. That forced Ickes to turn the complaint over to the Interior Department's Division of Investigations early in 1934. The inquiry by special agent Paul F. Cutter continued through the summer and eventually exonerated Smith, but Cutter was adamant about removing the checking station. Local residents derided it as a "nuisance station," and it clearly was a source of ill will toward the Park Service and Petrified Forest. "Tourists ought to be able to make up their own minds about visiting the monument," he pointed out. 23

Cutter was correct. Smith, in fact, inflated the number of visitors at the monument by registering motorists at his checking station. Harold Sellers Colton, custodian at Walnut Canyon National Monument near Flagstaff, happened to drive past Smith's station on U.S. 66 in May of 1934, and he encountered a ranger stopping all cars on the highway and registering them as visiting the monument. As a custodian, Colton recognized the ploy, which was not an uncommon one among Pinkley's custodians in the Southwest. Pinkley hoped, often in vain, that increasing the number of visitors would lead to additional funding. Money was allocated, at least partially, on the basis of the number of visitors recorded, and Colton realized that Smith "was seeing that his attendance was increased." Colton's complaint to Cammerer undoubtedly contributed to the arguments against the checking station. Walnut Canyon's custodian later heard that the offending ranger had been assigned elsewhere and that the registering of motorists had ended. "I was not very popular with Superintendent White Mountain Smith," Colton admitted. 24

Cutter recommended that Smith be transferred to another location without prejudice but left the decision to Albright. 25 Having found a competent superintendent for Petrified Forest, the Park Service director was willing to overlook the conflict with Julia Miller and her supporters. Smith stayed on at the monument. Mrs. Miller offered to sell her property to the government about a year later, but since it occupied land leased from the state of Arizona, the Park Service did not act. The state hesitated to cancel her lease and indeed renewed it the next year. The warring parties in northeastern Arizona continued to coexist after that-Julia Miller secure in her property with a new lease, and White Mountain Smith exonerated by the Interior Department but undoubtedly somewhat humbled by the encounter.

Julia Miller and her neighbors had much in common with similar small operators along Route 66 in the Southwest. Most simply sought to earn a living from the highway's traffic and resorted to the obvious kinds of establishments-gas stations, lunch counters, small stores, and motels. Miller's Lion Farm was a novel variation of the roadside "zoos" that often advertised rattlesnakes, pythons, and "reptile gardens" -anything to induce motorists to pull over. Once they stopped, travel-worn tourists would eat at the lunch counter and probably purchase a souvenir or two. 26 The Lion Farm, officially called the Painted Desert Park and Zoo of Native Animals, was particularly obtrusive, and Miller's use of "Painted Desert" in the name suggested a connection with the national monument. By today's standards Miller's operation would constitute an incompatible land use, not to mention a violation of state and federal laws. But in the 1930s, those restrictions were unknown and such establishments common.

The Lion Farm episode also represented a variation of the usual conflicts between national parks and concessionaires. At the major parks, superintendents often tangled with private companies like the Yellowstone Park Transportation Company and the Yosemite Park and Curry Company and their political allies. But few national monuments were large enough to require the services of entrepreneurs. Petrified Forest's only true concessionaire was Dick Grigsby, and his operation was small-a store and a few tourist cabins. But nearby businesses-the Nelsons' hotel in Adamana, the Painted Desert Inn, and the Lion Farm-could be similar sources of tension. Like formal concessions, they were dependent on the monument for their income, yet they remained independent of Park Service regulations. The conflict over the Lion Farm was not the last such encounter for Petrified Forest. Like a ghost from the past, the enterprise would reappear to frustrate several later superintendents.

The Interior Department investigation had distracted Smith at a critical time in the monument's development. Once free of the incubus of the investigation, he could turn his attention fully to the needs of Petrified Forest, where federal public works programs had made available generous funding and extensive workforces to undertake major improvements throughout this vastly expanded national monument.

For the drought-stricken, economically devastated American West of the 1930s, Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal held considerable promise. Depression, drought, and dust-the "formidable trio," as historian Richard Lowitt has described them-brought disaster to the country's arid regions. New Deal programs addressed soil erosion, range management, reclamation, and related conservation issues, and over the years the Roosevelt program presented the West with "an opportunity to transform itself." 27 While many such programs were utilitarian in their objectives, the New Deal, in fact, had its proponents of preservation. In much the same way that Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes had dominated conservation and reclamation programs in the West, this progressive Republican turned New Dealer also shaped measures to administer the country's national parks and monuments.

The most obvious feature of the New Deal for the parks and monuments was the sudden influx of cash. The amount of money allocated to the national parks skyrocketed during the New Deal years. The regular appropriations for the Park Service increased only modestly, but the Public Works Administration channeled $40,242,691 into the agency, and the Civilian Conservation Corps camps in various parks added another $82,250,467. Between 1935 and 1937 the Works Progress Administration added $24,000,000. Emergency conservation work in various park service units peaked in 1937, when the National Park Service counted 13,900 employees. These men were spread across a much expanded system that in 1940 encompassed 161 units, including 26 national parks and 82 national monuments in addition to historical parks, military parks, national battlefields, and historic sites-more than twice the number of units in 1933. 28

For the usually neglected national monuments like Petrified Forest, the New Deal years represented a watershed in their history. The domination of the national parks within the system finally was eclipsed, as officials recognized the significance of the monuments and other categories of reserves. As the Park Service extended its responsibilities to embrace such places, the value of the monuments became increasingly obvious, and administrators exerted more influence over them than ever before. In part, the new recognition of the national monuments reflected the expanded appropriations available through New Deal agencies. "The Park Service received so much money in the 1930s," historian Hal Rothman has written, "that it was able to spread its resources throughout the system." 29 Not only did the monuments receive generous funding, but the ccc workers provided much-needed labor, particularly in the natural, or scientific, reserves like Petrified Forest.

Initially, local administrators like Frank Pinkley and White Mountain Smith had no idea what to expect from the new Roosevelt administration, although it soon became apparent that additional funds would be forthcoming. Congress had established the Public Works Administration in June of 1933 with an appropriation of $3.3 billion under Title II of the National Industrial Recovery Act. The new agency could operate in a number of ways: by instituting its own programs, by allocating funds to other agencies to finance construction work, or by providing loans and grants to the states to initiate such work. The goal remained the same-to stimulate the country's lagging economy by employing idle workers. In the fall of 1933, PWA money trickled into Petrified Forest National Monument and was used to construct and pave footpaths in the various forests. Additional money was allocated for bridges and roadwork.

While various PWA projects were initiated around the country, New Deal officials made plans for an expanded federal works program. Harry Hopkins, head of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, was particularly anxious to put idle men to work and proposed such a program to Franklin Roosevelt in the fall of 1933. The country then was drifting into the fourth winter of the Great Depression, and Roosevelt liked the idea of a federal works program that would help some of the unemployed through one more winter. Since the PWA was slow getting under way, the president suggested that Hopkins might tap that agency's money to fund the new project. Out of this brief meeting came the Civil Works Administration, an emergency unemployment relief program. With funding from the Federal Emergency Relief Administration and the PWA, the CWA would employ men in a variety of federal, state, and local projects. Hopkins set a truly ambitious objective, announcing in mid-November 1933 that the agency expected to employ 4 million men by December 15. The target proved unrealistic; still, more than 2.6 million men were on CWA rolls on that date, and by the middle of January 1934, the 4 million mark had been passed.

In rural northeastern Arizona, the CWA jobs were accepted as gratefully as they were in such industrial centers as Detroit and Pittsburgh. Petrified Forest received a CWA allocation of $29,890 in early December to cover thirteen projects. "On December 7, I made a requisition on the National Re-employment Office for 25 men," Smith reported, "and on December 11, Civil Works Projects were under way." By the end of the first week, Smith had 69 men working; the number grew to 105 the following week, and at the end of December, Petrified Forest was employing 129 men on a variety of projects. Though the wages were meager, the money quickly entered the local economy. "It made possible a happy Christmas for many times the number employed," Smith acknowledged, "and has caused a brighter outlook for the coming year." 30

Most of the work performed at Petrified Forest involved trail and road construction, campground development, landscaping, and fenCing-projects that otherwise would have been delayed for years. More important, the CWA authorized an archaeological survey of sites within the monument. H. P. Mera of the Laboratory of Anthropology in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and his associate C. B. Cosgrove directed the endeavor. Their resulting list included 109 sites in and around Petrified Forest and provided an outline of the region's prehistory. They also excavated and restored Agate House, a Pueblo III site (A.D. 1000- 1250), and the Puerco Indian Ruin, a much larger Pueblo IV (A.D. 1250- 1450) complex built around a plaza near the Puerco River. The restored sites gave Petrified Forest two sophisticated archaeological exhibits and substantially expanded the possibilities for interpretive endeavors at the reserve. At the Flattops, a remote site in the southern part of the monument, Mera and Cosgrove's crew also excavated two pithouses in this Basketmaker II (up to A.D. 500-700) village, which includes the earliest known sites in the monument. 31

The Civil Works Administration came to an end in the spring of 1934; on April 19, Smith discharged the last seventeen CWA workers at Petrified Forest and totaled up his expenditures. If administering the programs had been frustrating from time to time, given the seemingly arbitrary dictates from Washington, Smith found some comfort in the fact that funds appropriated between December 1933 and April 1934 dwarfed the meager allocations that the monument typically received. Seldom had the Park Service ever allocated Petrified Forest more than a few thousand dollars. In the larger perspective of the Southwestern National Monuments, the contributions of the CWA were easily lost in the day-to-day frustrations of shifting supplies and men among scattered sites in remote monuments. Frank Pinkley, who supervised several hundred men scattered over fifteen projects, vowed that he would always remember the CWA with the same affection that the Navajo accorded their Long Walk to Bosque Redondo in 1864. 32

The Civil Works Administration was just the beginning, not the end, of federal projects destined to benefit Petrified Forest and its sister reserves. Hardly a month after Smith had said his good-byes to the last CWA workers, Lieutenant E. F. David arrived to establish a "fly camp" of fifteen Civilian Conservation Corps workers near the Puerco River. An unemployment relief measure, the Civilian Conservation Corps Reforestation Relief Act of 1933, authorized the Civilian Conservation Corps to provide work for 250,000 men between the ages of eighteen and twenty-five. As the measure's title indicates, the Corps was involved largely in conservation work, ranging from reforestation and prevention of soil erosion to flood control projects and improvements in national parks and monuments. Enrollees were stationed at work camps under the direction of U.S. Army officers and received $30 per month, part of which went to dependents back home. At the various National Park Service reserves, that agency's superintendent was responsible for carrying out the emergency conservation work programs.33

Much of the Civilian Conservation Corps activity consisted of mundane trail and road building and landscaping. Like ccc workers across the country, those at Petrified Forest planted trees, beginning with five hundred cottonwood slips set in place along the Puerco River. 34 Improved roads and trails made ruins and pictographs accessible to more tourists, and Petrified Forest's first Park Service naturalist, Myrl V. Walker, trained a contingent of ccc workers as guides to conduct nature walks. He found that the young men were dependable assistants for his geological research, so he also employed them on excavations at Blue Mesa. (See chapter 8 for details on Walker's career.)

Only a few ccc men were involved in the excavation, and the nature walks and related activities involved a small number more. The corps' major contribution at Petrified Forest was to be the virtual rebuilding of the Painted Desert Inn. Lore had originally purchased the Painted Desert land from the Santa Fe Railroad. The inn, constructed of stone and adobe by local Navajo workers, initially operated as a trading post and lunch counter. Lore had made few essential improvements and even continued to haul water to the inn rather than install a water system. The structure also lacked electricity and a telephone system, and there was no sewer system. When the Park Service purchased it, officials had determined to develop the inn and the surrounding area to allow visitors to enjoy the Painted Desert with at least a degree of comfort and convenience. 35

Smith and NPS architect Lorimer H. Skidmore inspected the inn thoroughly before renovation began. Their examination revealed structural weaknesses that had not been anticipated. Cracks had spread across the building's walls-not a surprising development in plastered walls. But a bit of scraping and probing beneath the plaster indicated why. The mortar that held the stone walls in place was not really mortar at all, but rather a sandy mud. The walls appeared relatively solid only because Lore's builder had covered the joints with sound mortar, apparently to prevent the dried mud from dissolving in the rain and sloughing off. The mud would have to be dug out and replaced with real mortar-an endeavor that would slow down renovation by several months. The inn rested on an equally shaky foundation, which necessitated construction of supports and underpinnings for the existing walls before they could be remodeled. 36

Renovation began in May of 1937, and the work proved excessively time-consuming. New construction undoubtedly would have proceeded much faster. By the end of the 1937 - 38 winter's work, much of the building's first floor had been completed. When moderate weather returned in the spring of 1938, the old roof was removed and the second-floor walls remodeled. Installation of the new roof beams followed, and masonry work began on both the inside and outside. Workers next installed structural columns with corbels, shaping them with an adze to provide a rustic finish. When commercial door and window frames were used, they were sandblasted to present aged surfaces. 37 Once the laborious work of rebuilding foundations and walls was completed, renovation went forward quickly, even though shortages of labor and supplies occasionally stalled the project.

Painted Desert Inn, 1940, following the renovation by the Civilian Conservation Corps (Photograph courtesy of Petrified Forest National Park)

By the end of the following year, renovation was nearly finished. In all, the two-story inn enclosed 7,520 square feet of space. Its stone and plaster walls were twenty-seven inches thick by the time renovation was complete. The building's architecture clearly reflected southwestern pueblo construction, though it was modified somewhat to incorporate Spanish colonial influences through the adzed beams and carved corbels and brackets. Skidmore's plans separated the building into two parts-one primarily a Park Service facility, the other an extensive area to be leased to a concessionaire.38 The latter included a lunch counter, kitchen, dining rooms, and an enclosed dining porch with access to decks that overlooked the Painted Desert. In this respect, the Painted Desert Inn functioned much as did Grand Canyon's EI Tovar, and indeed it became a landmark above the Painted Desert.

A tourist and a "Harvey Car" at Petrified Forest, early 1930s (Photograph from the Fred Harvey Collection, courtesy of the Museum of Northern Arizona)

The process of putting the final touches on the inn dragged through 1939, as did work on employees' residences and other facilities. On July 1 , 1940, Standard Concessions, Inc., of Chicago Signed the first contract to operate the Painted Desert Inn for three years. The company paid the government $10 per year for its concession to operate the inn, with net profits set at 6 percent. 39 On July 4, 1940, after almost three full years of work, the Painted Desert Inn opened its doors to tourists again. This time, travelers encountered a large, modern, efficiently operated facility, drastically different from the humble trading post and lunch counter that H. D. Lore had maintained.

Because of construction projects like the Painted Desert Inn and even the more prosaic work of reforestation and trail building, the Civilian Conservation Corps has left an enduring aura of goodwill. Indeed, its popularity has insulated it from much criticism, even though its construction projects in some parks and monuments adversely affected the environment. The corps proved adept at building facilities like those at Petrified Forest; all were labor intensive and employed young men idled by the depression-Washington's basic goal in the 1930s. Those projects, of course, encouraged tourists to visit the national parks and made their stay more pleasant.

Because facilities at Petrified Forest were so shabby, the ccc construction resulted in dramatic improvements from one end of the reserve to the other. The depression-era Civilian Conservation Corps offered a precedent for later federally sponsored improvements in such reserves. Slightly more than a decade elapsed between the end of the ccc and the initiation of another national park improvement plan-this one designated Mission 66. In its commitment to adding amenities for tourists, Mission 66 recalled its New Deal predecessor.

Completion of the inn coincided with another attempt by local businessmen and politicians to gain national park designation for Petrified Forest. The new movement was predictable, for during the 1930s Petrified Forest more than doubled its size through acquisition of the Painted Desert. Moreover, its facilities-once the source of embarrassment and derision-had improved immensely thanks to the PWA, CCC, and CWA. By the end of the depression decade, the monument in fact rather resembled a national park. Back in 1906, the expanses of petrified wood had provided sufficient justification to warrant its establishment as a national monument. But subsequent expansion, particularly the incorporation of Blue Forest and the Painted Desert, added to the original scientific site an expanse of scenic landscape-the ingredient that identified national parks and separated them from the monuments. If Petrified Forest's scenery did not quite match the monumental grandeur of Yellowstone or the Grand Canyon, it nonetheless possessed its own inherent, high-desert beauty and brilliant color.

The new park campaign began, as had others, in Holbrook. In the fall of 1937, members of the chamber of commerce and other leading citizens met with Arizona's Senator Henry Fountain Ashurst to discuss the project. White Mountain Smith, too, was invited, though his support was less than enthusiastic.40 In contrast, Senator Ashurst was a vigorous and vocal supporter. He had earlier supported a bill to establish Grand Canyon as a national park and was anxious to do the same for Petrified Forest. He introduced such a resolution in the Senate in June 1938, and the measure was sent on to the Committee on Public Lands and Surveys with instructions to investigate all matters relating to the feasibility of establishing Petrified Forest National Park. In turn, the details of the investigation were assigned to a subcommittee chaired by Ashurst and including Senators Carl Hatch of New Mexico and A. E. Reames of Oregon, which held hearings in northern Arizona in August.

The "suave and splendid Henry Fountain Ashurst" delighted his constituents in Holbrook when he chaired hearings to elicit public response to the projected name change for Petrified Forest. Testimony from local boosters stressed the need to expand tourism as a means to stimulate the economy of northeastern Arizona. E. V McEvoy was representative of the people in attendance as he explained to the committee that cattle ranching had virtually disappeared in the Little Colorado River Valley. Expanded tourism, he maintained, might take up the slack in the economy, and designation of Petrified Forest as a national park would likely have a positive effect. Others reinforced his argument, indicating that a good share of the residents of Navajo and Apache Counties supported the change in designation and expected to benefit economically from it. 41

The story was much the same when the hearings moved to La Posada in Winslow. A. B. Cammerer, now director of the National Park Service, attended both meetings and was one of the few people to question the park designation. He argued that Petrified Forest was the country's leading national monument, but that as a park it would not enjoy such high status. Indeed, ranking well behind Yellowstone, Grand Canyon, and Yosemite, Petrified Forest would find it difficult to compete for federal funds. He hinted, too, that in the future some federal money for the projected Petrified Forest National Park might be allocated to build hotels and restaurants within the park, and these would compete with businesses in Holbrook and Winslow.42

On January 23, 1939, Ashurst nevertheless introduced legislation to change Petrified Forest's name. By early spring, the bill was in trouble. Acting Interior Secretary Harry Slattery advised against it. "Petrified Forest is one of the oldest and most outstanding national monuments," he explained, "and is cited constantly in our public relations as an example of an ideal national monument." Its designation as a national park would lessen its prestige in comparison to Yellowstone, Grand Canyon, and "other large scenic parks." Secretary Harold Ickes later dashed the hopes of park proponents when he bluntly reminded them that "park designation was reserved for areas of scenic beauty; Monuments were objects or regions of peculiar scientific or historic interest." 43

Secretary Ickes read the Antiquities Act literally, and Petrified Forest fit precisely within the law's definition of a place of scientific interest. The addition of the Painted Desert was not sufficient to redefine the monument as an area of scenic beauty-at least not in the secretary's eyes. Petrified Forest's case was similar to that of Bandelier National Monument. In the early 1930s the National Park Service considered establishing Cliff Cities National Park in northern New Mexico. After an inspection of the Bandelier area, Roger Toll advised against a national park there because the scenery was not "sufficiently unusual and outstanding." He explained to Albright that the choice was "between having a large and important national monument and a rather small and unimportant national park." Monumentalism, it is evident, still shaped Washington's definition of national parks, even at the end of the 1930s. Petrified Forest in 1939 was in essentially the same situation as the Bandelier area eight years earlier. And like Bandelier it remained a monument, its proponents accommodating themselves to the deSignation of "outstanding national monument." 44

The perennial quest for a Petrified Forest National Park is understandable. Local residents and proponents perhaps did not understand the nuances between parks and monuments, but they clearly perceived that national parks were higher in status and more generously supported. Those characteristics easily translated into more federal expenditures on facilities and more tourists, too. The Park Service had fostered such impressions from the time of Mather and Albright. The agency's first director liked to employ such terms as "elevated" to park status, and he coined the phrase "national parkhood." The tendency of some monuments to move on to become national parks particularly irritated Frank Pinkley, who resented the practice. But National Park Service policy in the 1920s and 1930s seemingly encouraged the upgrading of at least certain scenic monuments to parks.45

Although people in Holbrook and Winslow would have much preferred a national park in their vicinity, Petrified Forest actually would have been better served by a policy that encouraged development and interpretation of unique resources. Important paleontological and archaeological work had occurred in Petrified Forest in the previous decades, but those scientific discoveries were only slowly integrated into interpretive programs, which usually consisted of displays and exhibits. Too often, visitors still missed the importance of the ancient environment in Petrified Forest and regarded the monument as a roadside attraction.

Whatever the Interior Department's rationale, local proponents were disappointed. Senator Ashurst was crushed; he described the defeat of the park measure as "the worst parliamentary defeat in 27 years as a senator." He had grown up in northern Arizona. and had often referred to Petrified Forest in his speeches. But Secretary Ickes, he lamented, says "it is worthy of being nothing more than a national monument. No longer shall I be known as the gay and blithesome Henry Fountain, but as the sad and dolorous Henry Fountain." 46

The defeat came in the spring of 1939, less than a year before completion of the Painted Desert Inn. And while Arizona's senior senator was deeply disappointed in the outcome, Smith and his staff at Petrified Forest had much to be thankful for. The Great Depression had not yet ended, but visitors were arriving in greatly increased numbers. After visitation plummeted in the early 1930s, the numbers gradually crept upward, reaching 105,396 at the end of the 1937 travel year, slightly more than in the record year of 1929. As oOune 30,1938, the figure was 109,331, with several months of heavy travel still to be recorded for the year. In mid-July of the following year, park officials noted that the number of visitors was close to 175,000.47

Moreover, the national monument designation was hardly a curse. Petrified Forest, by the Interior Department's estimation, was the country's leading monument, and at the end of the 1930s, it was not the forlorn collection of dilapidated shacks and bad roads that had greeted White Mountain Smith in 1929. Now augmented in size and facilities, it was a modern, efficient reserve, complete with museum, sophisticated archaeological displays, and a professional staff. For the Park Service, these added up to an ideal monument-not a national park. PWA funds and ccc workers clearly contributed to the monument's successful growth, and Smith had largely determined its course of development and quietly gUided its steady improvement. When he moved on in 1940 to Grand Teton National Park, he left his successor a facility that was well equipped to handle the growing number of tourists who stopped there. And when another national park movement inevitably blossomed, Petrified Forest and its personnel finally acquired the long-awaited national park designation.