7

AFTER THE WAR: MISSION 66 TO NATIONAL PARK AND BEYOND

I couldn't see the forest and I never did find the monument, but you sure do have some mighty pretty rocks around here!

American tourist, ca. 1955

The national parks and monuments, which had enjoyed generous federal support during the New Deal, were nearly abandoned during World War II. Shortly after Pearl Harbor, Congress reduced Park Service appropriations by 50 percent, and in 1942 the agency's headquarters were moved to Chicago to make room in Washington, D.C., for the military. The Park Service naturally terminated its travel promotion efforts, and by August of 1942 the Civilian Conservation Corps had largely departed from the parks and monuments. Appropriations fell off to only $5 million in 1943 and remained at that meager figure until 1947.

During the war, various commercial interests-ranchers, lumbermen, miners, and others-sought to exploit resources in the parks in behalf of the war effort. The military, too, expected to use these reserves, and in some instances their activities were extensive and detrimental. Much more damaging was the general neglect over nearly five years, for immediately after the war these deteriorating federal reserves were engulfed by a new generation of automobile tourists. In record numbers they traveled to parks and monuments that had lacked maintenance for years and now were reopening with reduced numbers of rangers, naturalists, and other key personnel. By the late 1940s, the national parks faced nearly insurmountable threats to their integrity.

Repairing and refurbishing older structures and adding modern facilities were immediate needs, and the Park Service had a useful precedent in the Civilian Conservation Corps. Its new program, Mission 66, was the brainchild of Park Service Director Conrad Wirth. Authorized in 1956, it projected a major, ten-year agenda to improve thoroughly the various Park Service reserves. Like its ccc predecessor, Mission 66 was designed to renovate and expand facilities for tourists. Officials gave comparatively little thought to environmental issues in the parks, and their limited perspective had prompted considerable criticism by the 1960s.

A new series of concerns, loosely described as "external threats," emerged in the 1970s and 1980s and constituted an additional burden for the Park Service. Incompatible land uses on neighboring terrain, ranging from real estate development to mining, soon endangered the integrity of some parks, and before long both air and water pollution threatened even isolated reserves. Such external developments occurred almost imperceptibly, but by the 1980s many observers recognized that the country's parks faced a new kind of danger. The National Parks and Conservation Association testified to the extent of the threat in 1982 when it published its important study, The National Parks in Crisis.

None of these problems were even vaguely anticipated in 1940, when supervision of America's "ideal national monument" passed to Thomas E. Whitcraft. Petrified Forest then was in the best condition in its history, the result of government expenditures and Civilian Conservation Corps labor during the previous decade. It had more than doubled in size during those years to embrace 145 square miles, nearly all of it owned by the federal government. The exceptions were 7,963 acres of privately owned land and a small parcel of 637 acres that belonged to the state of Arizona. Part of that was leased to the proprietor of the Painted Desert Park, the descendant ofJulia Miller's Lion Farm.

The new Painted Desert Inn was an immediate success. Easily accessible from u.s. 66, it became a popular stop for travelers, offering them an opportunity to relax, purchase a meal and drinks, and enjoy a panoramic view of the Painted Desert before continuing their journey across the high desert of northern Arizona. At the other end of the monument, Dick Grigsby retained his yearly Park Service permit to operate a general store and restaurant at the Rainbow Forest Lodge near the monument headquarters. 1

The new facilities easily handled the record 230,427 tourists in 1941, the last year of peace before the United States entered World War II. The impact of that conflict on Petrified Forest became apparent the following year, as the number of tourists tapered off to 189,772 and then plummeted to less than 50,000 in 1943-a 74 percent decrease. 2 Employees at the reserve enlisted in the armed services or were drafted. The Painted Desert Inn closed for the next two years, and Petrified Forest, like the other monuments and parks, operated on a much restricted basis.

Within a year of the war's end, the number of visitors to the monument already approximated prewar statistics and in subsequent years far surpassed them, reflecting a pattern common throughout all Park Service sites. For the first time in years, Americans finally had the opportunity to enjoy their automobiles free of the restrictions of wartime rationing, and they flocked to the country's national parks.

Others went West planning to stay there. More than 8 million people moved to the western states after World War II, 3.5 million of them settling in California. Route 66 bore the burden of these new migrants, who shared common experiences along the "mother road," as John Steinbeck had named it in The Grapes of Wrath. Across the Southwest, desolate stretches of the highway were interrupted only by occasional motels, eating places, and roadside attractions. "We just drove, and then we'd stay in a motel," recalled one postwar migrant, Cynthia Troup. "We stopped at some caverns; then we did Will Rogers." At the Painted Desert they pulled over to take a few photographs but by then were exceedingly anxious to get to Los Angeles-a sentiment undoubtedly shared by millions of others in the late 1940s and 1950s. 3

Only a small percentage of Route 66 travelers drove through Petrified Forest National Monument, but those visitors virtually overwhelmed the place and actually constituted a threat to its integrity as a scientific monument. They clearly attested to the popularity of Petrified Forest, and their numbers buttressed the arguments of those who still longed for the national park label. At the same time, though, officials were hard-pressed to maintain Petrified Forest as a unique natural wonder and not just another attraction along U.S. 66, which now blossomed with a variety of establishments catering to tourists.

With the burgeoning number of visitors came a resurgence of theft and vandalism, but Whitcraft lacked personnel to maintain effective patrols. His observations in the 1940s sound remarkably like those of William Nelson twenty years earlier, when automobiles were making their first appearances there. "The temptation for visitors to take small specimens of the fossil wood seems to be almost irresistible," the superintendent complained. Local residents, too, helped themselves to petrified wood and looted archaeological ruins, expecting to turn a profit by selling souvenirs to tourists.4

In June of 1947, the Fred Harvey Company took over the Painted Desert Inn concession. Shortly thereafter, the company called on Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter to oversee the decoration of the building's interior. Colter had been associated with Fred Harvey since 1902 as an architect and designer, and she had worked on nearly a dozen of the company's establishments in the Southwest, including Hopi House, EI Tovar, Hermit's Rest, and the Watchtower at Grand Canyon. The Spanish-Pueblo style of the Painted Desert Inn was one that Colter liked, and she relied on that motif in designing the interior.5

Fifteen years earlier when Colter had decorated the Watchtower, she had hired a young Hopi artist, Fred Kabotie (then a guide and musician at Grand Canyon), to paint murals of his people's legends in the Watchtower's Hopi Room. In 1947, she again engaged Kabotie, who painted two murals in the Painted Desert Inn dining room. One displays the importance of the eagle in Hopi life; for the other Kabotie depicted the journey to a salt lake near Zuni, recalling that the Hopi once traveled from their mesas through the Painted Desert on their way to the lake to collect salt. "To get this salt of theirs," Kabotie explained, "the Hopi really make a big ceremony out of it." The murals effectively place Petrified Forest within the cultural context of the region and portray the complexity of local Indian traditions. Kabotie's murals became a central attraction at the inn, and in 1976 the room was officially dedicated as the Kabotie Room. 6

The Painted Desert Inn had only a half-dozen small rooms for overnight guests, and it could not begin to meet the needs of the postwar automobile tourists. Superintendent Whitcraft resisted the inclination to build more accommodations within the reserve, maintaining instead that tourists should take advantage of motels, campgrounds, and restaurants in neighboring towns along Route 66. 7 In opposing construction of hotels and lodges, Whitcraft took an important step toward preserving Petrified Forest's essential integrity. Fewer guests staying overnight in the reserve would mean less theft and damage. Further, he anticipated recommendations that would be set forth in the 1960s by such organizations as the National Parks and Conservation Association, which criticized the road building and the accommodations that beckoned ever more visitors to the overcrowded national parks.

The number of visitors to Petrified Forest consistently set records. Once a source of pride and accomplishment, such statistics now engendered a degree of frustration. At the peak of the summer tourist season, Whitcraft had to acknowledge that .. our service to visitors was considerably below par." 8 Even with the ranger force expanded by an additional ten seasonal rangers, the superintendent could not adequately protect the petrified trees and archaeological sites. The amount of wood confiscated at checking stations provided a broad measure of the extent of theft occurring within the monument. In 1948, rangers recovered about nine thousand pounds of purloined souvenirs, indicating that on a typical day, tourists tried to get away with twenty to twenty-five pounds. And what they could not remove, they often damaged. The necessary routine of ministering to tourists meant that plans for expanded interpretive programs had to be limited.9

At the same time, the Painted Desert Inn, so meticulously restored by the Civilian Conservation Corps, already showed signs of deterioration. New cracks appeared regularly in its masonry walls, and William E. Branch, who succeeded Whitcraft in 1950, wondered whether the structure could ever be stabilized. The inn rested on unstable bentonite, which expands and contracts in response to the climate. It seemed likely that the clay had gradually dried and contracted during the dry years of the early 1950s, causing the building to settle month after month. For the time being, the inn seemed safe, but extensive repairs would be needed soon. Branch rather expected to see the structure collapse with the next major storm. By the spring of 1951, both Branch and Lyle Bennett of the Park Service's regional office in Santa Fe generally agreed that the Painted Desert Inn would eventually face condemnation. In the interim, cracks could be filled and walls replastered; but the historic building's fate seemed sealed. 10

The travelers who crowded into the snack bar and curio shop at the inn arrived via Route 66. While such interstate highways lured ever more tourists to the western parks and monuments, these routes often constituted indirect threats to the character of neighboring reserves by promoting incompatible land uses. As travel increased along U.S. 66,local businessmen naturally hoped to turn a profit by catering to motorists, continuing a practice that dated back to the 1920s. Postwar America was enjoying an economic boom, and the purchase of automobiles and subsequent cross-country travel was but one reflection of the country's affluence. All along Route 66, traffic invariably was heavy enough to support numerous roadside businesses. Combinations of gas stations and restaurants, usually operated by a husband and wife, were typical of such enterprises. Often a motel would be added, as business warranted, and in northern Arizona and New Mexico an "Indian trading post" could always attract motorists. The Jack Rabbit Trading Post, built in 1947 just west of Petrified Forest at Joseph City, has operated successfully ever since and has "made three or four owners rich," a local resident has remarked. 11 Often travelers themselves recognized the highway's potential for income and simply settled down and opened a gas station, motel, or restaurant. "Route 66 was a gold mine," one service station owner recalls 12

The Arizona Highway Department began planning the realignment and widening of U.S. 66 in the spring of 1951. Branch learned, to his pleasure, that the realigned highway would pass a mile and a half south of a roadside establishment called the Painted Desert Park. The had been the nemesis of Petrified Forest superintendents ever since the 1930s when Julia Miller established it. Located on state land within the monument's boundaries, the old Lion Farm was now leased to Charles Jacobs and several partners, who preferred to call it the Painted Desert Park. Its shoddy appearance had bothered Whitcraft, and Branch, too, despised the place. The name Painted Desert Park, unfortunately, easily misled tourists to believe that it was a Park Service operation. Whether intentionally or not , the owners profited from the travelers' mistakes. 13

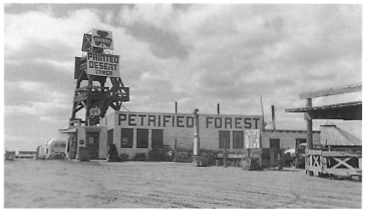

Painted Desert Park, 1957, on Route 66 near Petrified Forest (Photograph by F. Fagregren, courtesy of Petrified Forest National Park)

Jacobs hesitated to expand the operation, fearing that the new U.S. 66 would miss his land entirely. But he also owned additional nearby property along the highway and promptly built another roadside business-a trading post. Next to it he added a forty-foor-high observation tower from which tourists could view the Painted Desert. The place was .. quite an eyesore," Branch complained to Washington, and since it was near Petrified Forest, visitors assumed that it was part of the monument. Jacobs had so constructed the trading post that it could be moved to a new location in the event that the realigned highway was too far from his property. 14

An additional threat to the integrity of Petrified Forest National Monument also emerged in the early fifties, when northeastern Arizona was found to contain significant deposits of uranium. Prospectors filed claims on adjacent land and were eager to build access roads through the monument and even to prospect within its boundaries. Branch, of course, adamantly refused to consider such requests, aware that uranium mining represented the greatest threat ever to Petrified Forest. 15 It was not the mere mining of the radioactive ore that was dangerous, although that threat was substantial. Later accidents during uranium refining would pollute the ephemeral rivers that drain the area.

The overwhelming issue of the 1950s was neither uranium mining nor the Lion Farm, but the large number of tourists who drove through the monument. These hundreds of thousands of visitors attested to its popularity and prompted a resurgence of interest in gaining national park status for Petrified Forest. In Arizona Senator Carl Hayden, park proponents found a new champion for the cause; in 1955 Hayden introduced a measure to change the name of the reserve to Petrified Forest National Park. 16 That bill was unsuccessful, but with it the senator had initiated a process designed to achieve the coveted national park designation.

Revival of the park plan coincided with a major improvement program that was evolving within the National Park Service under the leadership of its new director, Conrad Wirth. The problems that frustrated personnel at Petrified Forest after World War II were only part of an extensive deterioration of all of America's parks and monuments. Although Park Service funding was once again above $30 million in 1950, Wirth realized that almost a decade of neglect had caused extensive deterioration to roads and facilities. Twenty-one new reserves had been added to the park system, and nearly twice as many people were visiting the parks and monuments as had done so in 1940. Appropriations consequently never kept pace with needs, and Wirth learned, too, that "Cold War costs left very little funding for the National Park Service." 17

Popular magazines dramatized the deterioration of the parks and monuments, reflecting the complaints of American tourists. In January 1955, Readers Digest published "The Shocking Truth about our National Parks," in which Charles Stevenson warned tourists that a trip to a national park was likely to be "fraught with discomfort, disappointment, even danger." Park Service personnel could not proVide essential services, and water, sewer, and electrical facilities were severely taxed. In an interview, Wirth conceded that "We actually get scared when we think about the bad health conditions." The Saturday Evening Post Similarly editorialized about the deplorable conditions and urged improvements. Historian Bernard De Voto, in his Harpers Monthly column, described the conditions he found during the course of a trip that took him through fifteen national parks in 1953. Some of the housing for Park Service employees reminded him of the Hoovervilles of the depression era, and salaries were so low that rangers' wives often went to work for concessionaires-"a highly undesirable practice," he added. It raised the specter of conflict of interest, since the Park Service regulated those very companies. Until Congress appropriated more funds, De Voto argued, there was no alternative but to close some of the parks, beginning with Yellowstone, Yosemite, Rocky Mountain, and Grand Canyon. The army could guard them until funds were forthcoming. 18

Such were the conditions that prompted the new Park Service director to initiate a massive, long-term program for the entire system. It was designated Mission 66; a special committee was charged to develop a ten-year plan to thoroughly improve America's parks and monuments by 1966-the fiftieth anniversary of the National Park Service. Specifically, the Mission 66 Committee had to address the somewhat contradictory objectives of providing Americans with the opportunity to enjoy their national parks while Simultaneously protecting these scenic, historic, and prehistoric areas from overuse. President Dwight Eisenhower added his support to the program in January 1956, and Mission 66 formally began on July 1. Congress, too, favored the measure, increasing Park Service appropriations from $32.9 million in the 1955 fiscal year to $48.8 million in 1957. Wirth and his Mission 66 staff estimated the costs of the program at slightly more than $786.5 million, but over its decade-long existence, Mission 66 expenditures substantially exceeded $ 1 billion. 19

Although Mission 66 was committed both to protecting scenic areas and to "providing optimum opportunity for public enjoyment," its planners favored projects that immediately benefited visitors. Roads, visitor centers, campgrounds, and similar facilities became the hallmarks of Mission 66 as the Park Service responded to the wants of the American tourist. Commitment to construction projects embodied at least implicit environmental threats. At worst, building hotels, restaurants, bridges, and roads could cause Significant environmental damage and also affect wildlife habitat. Catering to the wishes of vacationers naturally made some observers uneasy. In an essay titled "Man and Nature in the National Parks," F. Fraser Darling and Noel D. Eichhorn sharply criticized poliCies that facilitated travel and accommodations but virtually ignored environmental matters. As the authors pointed out, "Mission 66 has done comparatively little for the plants and animals." Writing in the Atlantic, Devereux Butcher, then editor of the National Parks Magazine, offered a Similarly harsh criticism. Still, such commentary came only after Mission 66 programs were well launched, and in contrast both tourists and the Park Service bureaucracy solidly supported the program. No one seriously considered limiting the number of visitors to the national parks; consequently, facilities had to be expanded. 20

Unlike Grand Canyon National Park to the west, renowned for its magnificent scenery, extensive hiking trails, campgrounds, and structures like El Tovar, Petrified Forest remained a relatively small operation. It offered only limited facilities for extended visits, and its essential objectives focused on the protection of its major resource, the ancient fossil trees. Naturalists and rangers developed interpretive programs to describe the Triassic environment, and they also integrated the history of the Anasazi and Mogollon inhabitants. But tourists stayed only briefly-usually about two hours. Typically they exited from Route 66, drove through the monument, perhaps stopping briefly at the Painted Desert Inn or at Rainbow Forest, and then continued to Holbrook, Winslow, and Flagstaff to the west or to any number of small roadside establishments that dotted the highway east of Petrified Forest.

Because of the drive-through nature of the reserve, its real needs were limited to improved facilities and interpretive programs. Noone advocated construction of hotels or even expansion of the monument's highways. The Painted Desert would remain free of excursions, and tourists would walk to the most important sites within the reserve. Initial Mission 66 plans for Petrified Forest projected only an expansion of facilities to accommodate visitors and construction of housing for employees. Along with those recommendations came the Park Service's acknowledgment that Petrified Forest now finally deserved to be a national park. The incorporation of that designation in Mission 66 plans was the crucial factor in the reserve's eventually successful transition to a national park.

Petrified Forest was the beneficiary of gradually evolving attitudes about national parks. By the 1960s, the definition of parks had broadened considerably to accommodate a diversity of reserves ranging from national seashores and lakeshores to urban recreation areas. Many park proponents still remained emotionally attached to monumentalism, but the political reality was that the park movement was changing. 21 A wider variety ofsites would soon come under federal protection. The growing number of visitors at Petrified Forest attested to its popularily and importance in the park system and undoubtedly convinced Mission 66 planners of its national significance. A last factor buttressed the case for park status. The name change would cost very little, since nearly all of the land already was in federal possession, and no expansion was planned. 22

Senator Hayden, in the meantime, continued his efforts in behalf of the national park designation, introducing a bill on June 21, 1957, to authorize the change. In the House of Representatives, Stewart Udall of Arizona introduced similar legislation. This new measure included a critical provision that would bestow the park title only after the Interior Department had acquired the remaining private lands within the boundaries of the monument. Land exchanges would take care of some of the transfers, but other acreage would have to be purchased. Mission 66 helped here, since funding had been included for that purpose. Congress went along with the legislation, and with Eisenhower's signature on March 28, 1958, it became law. Petrified Forest could become a national park, the new law decreed, but only after title to the private lands was vested in the federal government.23

The national park measure engendered only modest opposition, and Virtually none came from Arizonans. But the National Parks and Conservation Association consistently opposed the name change. Petrified Forest, one brief editorial pointed out, was an exceptional national monument, though it clearly lacked the "outstanding scenic magnificence, varied natural features," and other characteristics that identified national parks. Devereux Butcher was more explicit. Congress had passed the measure with no opposition, he told Conrad Wirth, although he had done his best to prevent it. From Butcher's perspective, the national park designation for Petrified Forest was "the most flagrant violation of basic protective park principles to have occurred in recent years." 24

Butcher's critique raised an important point about national parks in postwar America. By the 1960s, Butcher had gained notoriety as one of the more vocal critics of the overdevelopment of national parks and monuments through Mission 66. His essential aim was to "keep the national parks, as nearly as possible, as nature made them." Popularizing and commercializing these reserves, he maintained, is "to cheapen them to the level of ordinary playgrounds." 25

As for designating Petrified Forest a national park, the National Parks and Conservation Association feared that the move was just another means to attract more visitors to the area and to secure private inholdings. At least on the first point, Butcher and the association were correct. Residents of sparsely settled northeastern Arizona had always pushed for the national park status precisely because they anticipated increased tourism and, with it, a stimulus to the local economy. Holbrook, a half hour's drive to the west, stood to benefit particularly, as did St. Johns and the small towns in the White Mountains south of the park. Arizonans were not looking for concessions within the new park; rather, they hoped to attract more visitors to their nearby towns and businesses. Park status therefore did not mean extensive commercialization of Petrified Forest; it projected only badly needed facilities and interpretive measures. More tourists could actually visit Petrified Forest National Park, but the Park Service would not have to cater to their needs with hotels, campgrounds, and other tourist attractions. Nearby towns, connected to Petrified Forests by modern highways, reduced the need for such facilities within the reserve.

Contrary to Butcher's contention, the park bill did not guarantee private holdings but rather provided a means to eliminate many of them. Throughout the monument's history, private lands had been a nuisance at best for the reserve's staff. Now these holdings-none of them compatible with park use-were scheduled for elimination. In the meantime, they threatened to delay, perhaps to prevent entirely, the long-awaited emergence of Petrified Forest National Park.

For the next several years, Petrified Forest's superintendents Fred Fagergren and Charles E. Humberger worked doggedly to extinguish private property titles, including that of the Painted Desert Park. That process ended only in April of 1962, when the last of the land was transferred to the Park Service. In the meantime, Mission 66 projects were under way, the most dramatic among them the reserve's visitor center near Route 66. The concept of visitor centers grew out of the realization that the small museums so characteristic of many parks and monuments were simply inadequate to meet the demands of postwar tourists. In response, Park Service architects designed open structures that included information about the park, interpretive displays, and other facilities. 26 The new Mission 66 visitor center at Petrified Forest included the park headquarters, housing for employees, and utility areas.

The new facility opened to the public in August of 1962. The Park Service scheduled an open house at this most recent Mission 66 creation on August 28 and also used the occasion to mark the forty-sixth anniversary of "Founders Day" in 1916, when the Park Service was established. 27 Two months later, Fagergren was promoted to the superintendency of Grand Teton National Park, and Petrified Forest, still a national monument, became the charge of Charles E. Humberger, formerly an assistant superintendent at Zion National Park in Utah.

In a general way, Fagergren's tenure at Petrified Forest had paralleled that of White Mountain Smith during the depression years, when federal funds had virtually created a modern national monument. Fagergren's task had been to supervise a second phase of modernization under Mission 66, and like Smith, he had taken on the responsibility for eliminating private lands within the reserve. Remarkably, the Lion Farm, albeit with a new name, had persisted beyond the tenure of both superintendents, although Fagergren acquired most of its holdings before he departed. Smith and Fagergren both witnessed the blossoming of national park movements during their superintendencies. The earlier endeavor had been dashed ingloriously by the Interior Department itself, but the recent quest succeeded.

Only two months after Fagergren's departure, his monument became a national park. On December 8, 1962, fifty-six years after Theodore Roosevelt had proclaimed it a national monument, Petrified Forest became the country's thirty-first national park. 28 Symbolically, Fred Harvey ended its operation at the historic but deteriorating Painted Desert Inn and took over as concessionaire at the new Petrified Forest Visitor Center, occupying a modern, efficient establishment called the Painted Desert Oasis.

Mission 66 and national park status resulted in one undeniable accomplishment: the Park Service now held title to all of the land within the boundaries of Petrified Forest. In the future there would be no incompatible land uses within the reserve-no lion farms, private "parks," trading posts, or similar enterprises. Extensive physical improvements had been added as well, and the new park derived some publicity benefits as a result of the name change. In the 1960s, the Park Service took an additional step to underwrite the reserve's integrity by proposing more than fifty thousand acres for wilderness designation. Congress responded favorably and in 1970 established Petrified Forest National Wilderness Area. 29

In some of its structures, such as the Painted Desert Oasis and the visitor center, Petrified Forest clearly reflected the penchant among Mission 66 planners to cater to the wishes of visitors. At the new park, these activities were not particularly disruptive, and Mission 66 actually funded excavation and stabilization work at the Puerco Indian Ruin-an important expansion of interpretive activities. The real shortcoming at Petrified Forest was the fact that officials missed an opportunity to capitalize fully on the park's differences from its monumental, scenic sister institutions by developing further interpretive programs that reflected its ancient environment and the cultures of prehistoric inhabitants.

Although Mission 66 helped the staff at Petrified Forest to deal more efficiently with visitors, the program was of little assistance in meeting challenges that developed outside the park boundaries-" external threats," as the Park Service designated them. America's affluent society grew immensely after World War II, and so did its demands for energy, building materials, recreation, and living space. Nearly all of the parks and monuments faced some degree of danger from developments beyond their boundaries. But in the Southwest, with its ideal hydroelectric dam sites, extensive deposits of uranium, coal, and petroleum, and fast-growing population, the external threats became substantial. Upstream from Grand Canyon National Park, the Bureau of Reclamation had built the massive Glen Canyon Dam, and additional dams were proposed within the park itself. A smoky haze-traced to regional power plants among other sources-often obscures views at Grand Canyon, which also is plagued by noise generated by sightseeing helicopters and small airplanes.

Petrified Forest's very remoteness had given it a degree of protection throughout much of its history. Theft and vandalism were ever present, but the reserve had been spared some of the problems that plagued larger parks like Yosemite, Grand Canyon, and Yellowstone. It obviously contains no lucrative dam sites, and resort owners saw little potential in the area. Nor did that part of the Southwest appeal to developers seeking to sell vacation home sites.

Land ownership around Petrified Forest was in a state of flux in the decades after the reserve became a national park. The Arizona and New Mexico Land Company, as well as the state of Arizona, were anxious to consolidate their holdings in northeastern Arizona-much of it scattered in a checkerboard fashion along the Santa Fe's right-of-way. In particular, the land company wanted to sell out its holdings in the area and obtain land elsewhere that had more potential for profitable development. Historically, cattle ranches had bordered much of the reserve, and stock raising was generally compatible with its environment. Actually, ranches had served effectively as buffers to insulate Petrified Forest from incompatible outside incursions.

In the 1970s, local ranchers began to subdivide their ranges into forty-acre homesites, and that development led to an influx of people and to the construction of homes, garages, barns, and similar structures. On some of the homesites near the park boundaries, new landowners had put up a variety of shacks; others moved into trailers, and one was living in an abandoned school bus. Such structures detracted from the area's scenic vistas, but the Park Service was powerless to intervene on neighboring private land. 30 Naturally, the agency did not look forward to changes in ownership in the vicinity of the park, and it was clear that the unobstructed natural views in all directions were about to be modified. Gas and oil exploration posed another potential threat, as energy companies stepped up their activities in the aftermath of the oil shortages that grew out of the political turmoil in the Middle East. These enterprises would have an obvious visual impact, not to mention the potential for pollution.31

From a number of places in the park-Painted Desert, Blue Mesa, Twin Buttes, and others-visitors enjoy spectacular vistas of the surrounding high desert. More than a hundred miles to the west, the majestic San Francisco Peaks are visible, towering above the Colorado Plateau. Snow capped from fall to late spring, these sacred mountains of the Navajo and Hopi define the western horizon. To the south are the White Mountains-not so high or spectacular or snow capped-but nonetheless important visual assets. The Painted Desert itself embraces the northern part of the park and represents its greatest scenic attribute, challenging in its subtle tones the colors of the Grand Canyon if not its dimensions.

The clear air of Petrified Forest is also a major asset, and by the 1980s, park personnel worried that any deterioration in its quality would diminish the scenic vistas. The 1977 Clean Air Act Amendments deSignate Petrified Forest as a Class I area, and a program was established to monitor air quality and identify adverse developments. Only a few years earlier, the Arizona Public Service Company had constructed a new coal-fired power plant at Joseph City, just thirty miles west of the park. The installation, according to a 1981 resource management plan for Petrified Forest, had already had an adverse impact on long-distance vistas. More recent studies also have documented the existence of intermittent pollution at Petrified Forest. 32

Much of the time, the park's air quality remains outstanding, and visitors still appreciate the colorful panoramas of the Painted Desert as well as the long-distance vistas. Personnel there also have been attentive to the importance of natural quietness within the reserve. Officials have worked with civilian pilots and the United States Air Force to ensure that low-flying aircraft do not degrade the natural quiet. The commitment stands in contrast to the approach taken at Grand Canyon, the site of numerous daily overflights. Small tourist planes from Las Vegas and other regional cities ferry tourists along the route of the canyon and, until recently, were allowed to fly below the rim.

Problems of noise and visual pollution were minor in comparison to the threat of contamination in the Puerco River. In 1979 tailings had spilled into the Puerco from the United Nuclear Corporation's dam at Gallup, New Mexico, 150 miles to the east. Park officials soon became concerned about the increased flow in this normally ephemeral stream, as erosion actually threatened Petrified Forest's main well and pump near the Puerco bridge. Radiation levels near the park remained within acceptable levels, but at Sanders, Arizona, only 30 miles away, measurements revealed increased radiation. Installation of pilings along the Puerco's north bank checked erosion and secured the park's water supply, but pollution still represented a threat. Again in 1986, United Nuclear discharged radioactive effluent into the river, causing a substantial increase in its flow. From Gallup westward into Arizona, the Puerco became a perennial stream. United Nuclear and other mines around Gallup closed before the end of the year, and the spread of surface radiation downstream ceased. No one knew what effect the effluent had had on shallow wells along the Puerco streambed, but the major threat had abated. 33

The danger of such pollution at Petrified Forest was a measure of the complexity of maintaining the integrity of a national park in modern America. The history of the reserve in the decades after World War II illustrates that even a remote location cannot offer full protection from the intrusions of contemporary society. The park itself remained remarkably undisturbed, for it had experienced little development beyond the Painted Desert Inn and the Rainbow Forest complex. Even after the new construction at the Painted Desert Visitor Center and administrative headquarters, which are clearly separated from the deposits of petrified wood, archaeological sites, and important scenic places, the park retains much of its unspoiled character. It offers no overnight accommodations (except to a few backpackers), so the blight of hotels, campgrounds, and similar developments do not interfere with the visitor's park experience. The park actually operates in much the way that critics of the Park Service and Mission 66 advocated in the 1960s. The internal park highway has been widened and improved over the years, but Petrified Forest has been spared massive new road construction. Tourists can easily drive through it, spending as many hours as they wish, but they must find motels and campgrounds in neighboring towns.

While personnel can exercise considerable control over the internal environment, they are at the mercy of any outside developments, although federal offices such as the Environmental Protection Agency have the power to intervene in the park's behalf. The future of Petrified Forest depends on the federal government's ability to protect the reserve against intrusions from outside. The clean air, nearly pristine environment, and long-range vistas are all subject to whatever developments occur in northeastern Arizona-an area once thoroughly removed from the pressures of civilization.