This chapter discusses services used to distribute information about machines, people and network addresses. This includes naming services, which translate hostnames to IP addresses (and vice versa) and more general directory services. The Internet standard for name service is the Domain Name System (DNS), but other protocols, including the Network Information Service (NIS) and the Windows Internet Name Service (WINS), are used to distribute this information within individual networks. In addition, this chapter discusses the Windows Browser, which is also used by human beings to find machines; the Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP), which is used for a wide range of directory information; the finger program, which provides information about people; and the whois program, which provides information about network ownership.

The Domain Name System (DNS) is an Internet-wide system for the resolution of hostnames and IP addresses. You will also see it called Domain Name Service. Unfortunately for the sanity of administrators, the Domain Name System and Microsoft Windows domains are different things. Microsoft Windows machines can and do use DNS (and it is required for Windows 2000), but a Windows domain is fundamentally a unit of authority that may or may not control the name of a machine. (Windows domains are discussed further in Chapter 21 ; they are also relevant to the Browser, which is discussed later in this chapter.)

DNS is a distributed database system that translates hostnames to IP addresses and IP addresses to hostnames (for instance it might translate hostname miles.somewhere.example to IP address 192.168.244.34). DNS is also the standard Internet mechanism for storing and accessing several other kinds of information about hosts; it provides information about a particular host to the world at large. For example, if a host cannot receive mail directly, but another machine will receive mail for it and pass it on, that information is communicated with an MX record in DNS.

DNS clients include any program that needs to do any of the following:

Translate a hostname to an IP address

Translate an IP address to a hostname

Obtain other published information about a host (such as its MX record)

Fundamentally, any program that uses hostnames can be a DNS client. This includes essentially every program that has anything to do with networking, including both client and server programs for Telnet, SMTP, FTP, and almost any other network service. DNS is thus a fundamental networking service, upon which other network services rely. DNS service is a complicated subject, which we cannot discuss fully here. For more information about DNS, consult a DNS reference (for instance, DNS and BIND by Paul Albitz and Cricket Liu, O'Reilly & Associates, 1998).

Other protocols may be used to provide this kind of information. For example, NIS and WINS are used to provide host information within a network. However, DNS is the service used for this purpose across the Internet, and clients that need to access Internet hosts will have to use DNS, directly or indirectly. On networks that use WINS, NIS, or other methods internally, the server for the other protocol usually acts as a DNS proxy for the client. Many clients can also be configured to use multiple services, so that if a host lookup fails, it will retry using another method. Thus, it might start by looking in NIS, which will show only local hosts but try DNS if that fails, or it might start by looking in DNS and then try a file on its own disk if that fails (so that you can put in personal favorite names, for example). We'll discuss this later in this chapter. (One debugging tool that is very useful in this situation is nslookup, which is a pure DNS client. If the information you get from nslookup is not the same as the information you get when you try to resolve a hostname in another program, you know that the other program is not getting its information from DNS.)

In Unix, DNS is implemented by the Berkeley Internet Name Domain (BIND). On the client side is the resolver, a library of routines called by network processes. On the server side is a daemon called named (also known as in.named on some systems). In Microsoft Windows, the client-side libraries are less localized because of the complex possibilities for mixing native Microsoft protocols for name resolution with DNS. The server side is a server called Microsoft DNS Server, which is designed to be highly interoperable with BIND. BIND and Microsoft DNS Server are never perfectly interoperable—each one has its own special features and interpretations of the standards that are changed with each release—but they have a large overlap and are rarely actually incompatible.

DNS is designed to forward queries and responses between clients and servers, so that servers may act on behalf of clients or other servers. This capability is very important to your ability to build a firewall that handles DNS services securely.

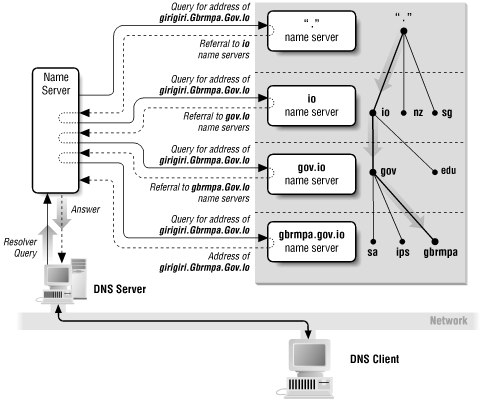

How does DNS work? Essentially, the most common procedure goes like this: When a client needs a particular piece of information (e.g., the IP address of host ftp.somewhere.example), it asks its local DNS server for that information. The local DNS server first examines its own cache to see if it already knows the answer to the client's query. If not, the local DNS server asks other DNS servers, in turn, to discover the answer to the client's query. When the local DNS server gets the answer (or decides that it can't for some reason), it caches any information it got[1] and answers the client. For example, to find the IP address for ftp.somewhere.example, the local DNS server first asks one of the public root name servers which machines are name servers for the example domain. It then asks one of those example name servers which machines are name servers for the somewhere.example domain and then it asks one of those name servers for the IP address of ftp.somewhere.example.

This asking and answering is all transparent to the client. As far as the client is concerned, it has communicated only with the local server. It doesn't know or care that the local server may have contacted several other servers in the process of answering the original question.

The DNS protocol does not require servers to act like this. Servers do not have to maintain local caches, and they do not have to pass queries to other servers (they can refer the client to another server instead). In practice, however, all name servers in widespread use provide both caching and recursion (which is the term used in DNS circles to refer to the process where the server asks other servers if it cannot find the answer).

There are two types of DNS network activities: lookups and zone transfers. Lookups occur when a DNS client (or a DNS server acting on behalf of a client) queries a DNS server for information—for example, the IP address for a given hostname, the hostname for a given IP address, the name server for a given domain, or the mail exchanger for a given host. Zone transfers occur when a DNS server (the secondary server) requests from another DNS server (the primary server) everything the primary server knows about a given piece of the DNS naming tree (the zone). Zone transfers happen only among servers that are supposed to be providing the same information; a server won't try to do a zone transfer from a random other server under normal circumstances. You will sometimes see random zone transfer requests because people occasionally do zone transfers in order to gather information (which is OK when they're calculating what the most popular hostname on the Internet is, but bad when they're trying to find out what hosts to attack at your site). Some DNS servers allow access control lists to restrict which hosts can perform zone transfers. Adding an access control list doesn't really gain you very much; it might give you some protection against bugs in the implementation of zone transfers or may hinder an attacker using a script. However, the information can still be obtained by performing lots of individual DNS lookups.

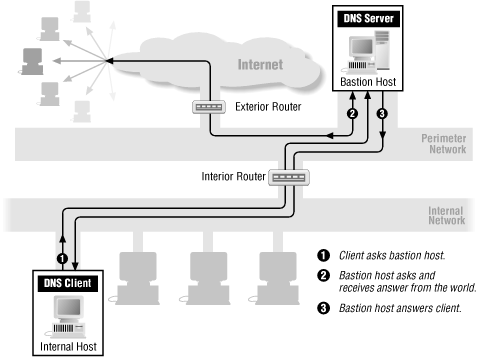

For performance reasons, DNS lookups are usually executed using UDP. If some of the data is lost in transit by UDP (remember that UDP doesn't guarantee delivery), the lookup may be redone using TCP. There may be other exceptions (nothing actually requires clients to try UDP first or to ever try TCP at all). Figure 20.1 shows a DNS name lookup.

A DNS server uses well-known port 53 as its server port for TCP and UDP. It uses a port above 1023 for TCP requests. Some servers use 53 as a source port for UDP requests, while others will use a port above 1023. A DNS client uses a random port above 1023 for both UDP and TCP. You can thus differentiate between the following:

- A client-to-server query

Source port is above 1023, destination port is 53.

- A server-to-client response

Source port is 53, destination port is above 1023.

- A server-to-server query or response

At least with UDP on some servers where both source and destination port are 53; with TCP, the requesting server will use a port above 1023. Servers that do not use UDP source port 53 are indistinguishable from clients.

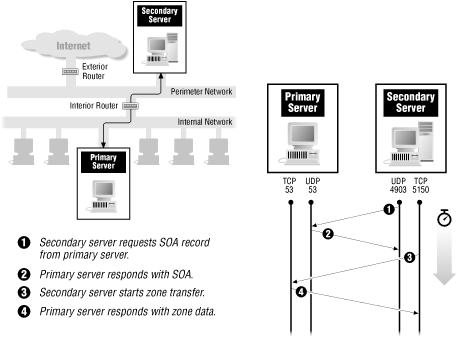

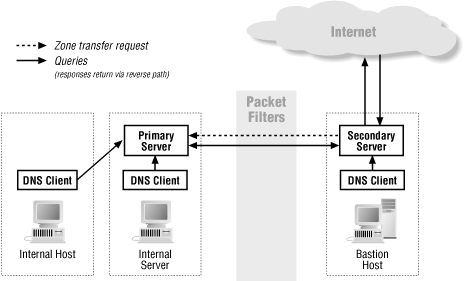

DNS zone transfers are performed using TCP. The connection is initiated from a random port above 1023 on the secondary server (which requests the data) to port 53 on the primary server (which sends the data requested by the secondary). In order to figure out when to transfer the zone, a secondary server must be able to do a regular DNS query of a primary server or to get a notification update (called a DNS NOTIFY) from the primary server. These notifications behave like normal server-server queries, except that they go from the primary to the secondary. Figure 20.2 shows a DNS zone transfer.

If your primary and secondary servers both support DNS NOTIFY so that the primary server can notify the secondary server of changes, you only need to allow TCP between them. DNS NOTIFY is required to be able to use TCP when UDP is unavailable, although it defaults to UDP. If you cannot use DNS NOTIFY, you may have to allow UDP between the two servers because the secondary server must be able to query the primary server and is not required to use TCP to do so. Most servers will fail over to TCP if UDP is unavailable, but the only way to be sure is to check what the servers you are running actually do. Note that DNS NOTIFY is a relatively recent addition and not all servers support it.

Direction | SourceAddr. | Dest.Addr. | Protocol | SourcePort | Dest.Port | ACKSet | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

In | Ext | Int | UDP | >1023 | 53 | [2] | Query via UDP, external client to internal server |

Out | Int | Ext | UDP | 53 | >1023 | [2] | Response via UDP, internal server to external client |

In | Ext | Int | TCP | >1023 | 53 | [4] | Query via TCP, external client to internal server |

Out | Int | Ext | TCP | 53 | >1023 | Yes | Response via TCP, internal server to external client |

Out | Int | Ext | UDP | >1023 | 53 | [2] | Query via UDP, internal client to external server |

In | Ext | Int | UDP | 53 | >1023 | [2] | Response via UDP, external server to internal client |

Out | Int | Ext | TCP | >1023 | 53 | [4] | Query via TCP, internal client to external server |

In | Ext | Int | TCP | 53 | >1023 | Yes | Response via TCP, external server to internal client |

In | Ext | Int | UDP | 53 | 53 | [2] | Query or response between two servers[9] via UDP |

Out | Int | Ext | UDP | 53 | 53 | [2] | Query or response between two servers[9] via UDP |

In | Ext | Int | TCP | >1023 | 53 | [4] | Query or zone transfer request from external server to internal server via TCP |

Out | Int | Ext | TCP | 53 | >1023 | Yes | Response (including zone transfer response) from internal server to external server via TCP |

Out | Int | Ext | TCP | >1023 | 53 | [4] | Query or zone transfer request from internal server to external server via TCP |

In | Ext | Int | TCP | 53 | >1023 | Yes | Response (including zone transfer response) from external server to internal server via TCP |

[2] UDP has no ACK equivalent. [4] ACK is not set on the first packet of this type (establishing connection) but will be set on the rest. [9] Not all servers use 53 as a source port for UDP; some will use a port above 1023, like other clients. | |||||||

DNS is structured so that servers normally act as proxies for clients. It's also possible to use a DNS feature called forwarding so that a DNS server is effectively a proxy for another server. The remainder of this DNS discussion describes the use of these built-in proxying features of DNS.

In most implementations, it would be possible to modify the DNS libraries to use a modified-client proxy. On machines that do not support dynamic linking, using a modified-client proxy for DNS would require recompiling every network-aware program. Because users don't directly specify server information for DNS, modified-procedure proxies seem nearly impossible.

DNS is a tree-structured database, with servers for various subtrees scattered throughout the Internet. A number of defined record types are in the tree, including the following.[14]

Record Type | Usage |

|---|---|

A | Translates hostname to IP address |

PTR | Translates IP address to hostname |

CNAME | Translates host alias to hostname ("canonical" name) |

HINFO | Gives hardware/software information about a host |

NS | Delegates a zone of the DNS tree to some other server |

SOA | Denotes start of authority for a zone of the DNS tree |

MX | Specifies another host to receive mail for this hostname (a mail exchanger) |

In fact, there are two separate DNS data trees: one for obtaining information by hostname (such as the IP address, CNAME record, HINFO record, or MX record that corresponds to a given hostname), and one for obtaining information by IP address (the hostname for a given address).

For example, the following is a sample of the DNS data for a fake domain somebody.example :

somebody.example. IN SOA tiger.somebody.example. root.tiger.somebody.example. (

1001 ; serial number

36000 ; refresh (10 hr)

3600 ; retry (1 hr)

3600000 ; expire (1000 hr)

36000 ; default ttl (10 hr)

)

IN NS tiger.somebody.example.

IN NS lion.somebody.example.

tiger IN A 192.168.2.34

IN MX 5 tiger.somebody.example.

IN MX 10 lion.somebody.example.

IN HINFO INTEL-486 BSDI

ftp IN CNAME tiger.somebody.example.

lion IN A 192.168.2.35

IN MX 5 lion.somebody.example.

IN MX 10 tiger.somebody.example.

IN HINFO SUN-3 SUNOS

www IN CNAME lion.somebody.example.

wais IN CNAME lion.somebody.example.

alaska IN NS bear.alaska.somebody.example.

bear.alaska IN A 192.168.2.81This domain would also need a corresponding set of PTR records to map IP addresses back to hostnames. To translate an IP address to a hostname, you reverse the components of the IP address, append .IN-ADDR.ARPA, and look up the DNS PTR record for that name. For example, to translate IP address 1.2.3.4, you would look up the PTR record for 4.3.2.1.IN-ADDR.ARPA.

2.168.192.IN-ADDR.ARPA. IN SOA tiger.somebody.example.root.tiger.somebody.example. (

1001 ; serial number

36000 ; refresh (10 hr)

3600 ; retry (1 hr)

3600000 ; expire (1000 hr)

36000 ; default ttl (10 hr)

)

IN NS tiger.somebody.example.

IN NS lion.somebody.example.

34 IN PTR tiger.somebody.example.

35 IN PTR lion.somebody.example.

81 IN PTR bear.alaska.somebody.example.Some security problems with DNS are described in the following sections.

The first security problem with DNS is that many DNS servers and clients can be tricked by an attacker into believing bogus information. Many clients and servers don't check to see whether all the answers they get relate to questions they actually asked, or whether the answers they get are coming from the server they asked. A machine that asks for the IP address of "malicioushost" and gets back the requested information plus a false IP address for "trustedhost", as well, may cache the extra answer without really thinking about it and answer later queries with this bogus cached data. This lack of checking can allow an attacker to give false data to your clients and servers. For example, an attacker could use this capability to load your server's cache with information that says that the IP address of a machine the attacker controls maps to the hostname of a host you trust for password-less access via rlogin. (This reason is only one of several why you shouldn't allow the BSD "r" commands across your firewall; see the full discussion of these commands in Chapter 18.)

Tip

Later versions of DNS for Unix (BIND 4.9 and later) check for bogus answers and are less susceptible to these problems. Earlier versions, and DNS clients and servers for other platforms, may still be susceptible.

Some Unix DNS implementations will accept and cache answers even when they haven't made a query; some Microsoft implementations will crash if they receive an unrequested answer. Both of these behaviors are undesirable and have been eliminated by recent releases. Windows 2000 by default will only accept answers to queries but will accept those answers from any server. It can be configured to require the response to come from a queried server and should be on security-critical machines.

Not only are some DNS implementations vulnerable to hostile answers, some are vulnerable to hostile questions. In particular, some DNS servers have problems with buffer overflows and may crash or execute hostile code if a query is too long. (See Chapter 13, for more information about buffer overflow attacks.) If your log files show queries that contain very long "hostnames" containing control characters, people are probably attempting buffer overflow attacks. Again, vendors have been working on eliminating these vulnerabilities, but you should check to make certain the appropriate patches have been made in the version you are running. There are known problems with versions of BIND 4 prior to 4.9.7 and BIND 8 prior to 8.1.2 (note that this does not guarantee that later versions don't also have problems that haven't been found yet).

The attack that uses bad cached data to give you an apparently trustworthy hostname for an untrusted host points out the problem of mismatched data between the hostname and IP address trees in DNS. In a case like the one we've described, if you look up the hostname corresponding to the attacker's IP address (this is called a reverse lookup), you get back the name of a host you trust. If you then look up the IP address of this hostname (which is called a double-reverse lookup), you should see that the IP address doesn't match the one the attacker is using, which should alert you that something suspicious is going on. Reverse and double-reverse lookups are described in more detail later in this DNS discussion.

There are perfectly valid reasons for these checks to return inconsistent values; no rules require a forward and reverse lookup to return consistent information. In fact, when DNS is used for load balancing between servers, it is difficult to arrange for this consistency. In these situations, DNS is being used to determine the location of a service rather than the IP address of an individual host.

Any program that makes authentication or authorization decisions based on the hostname information it gets from DNS should be very careful to validate the data with this reverse lookup/double-reverse lookup method. In some operating systems (for example, SunOS 4.x and later), this check is automatically done for you by the gethostbyaddr( ) library function. In most other operating systems, you have to do the check yourself. Make sure that you know which approach your own operating system takes and that the daemons that are making such decisions in your system do the appropriate validation. (And be sure you're preserving this functionality if you modify or replace the vendor's libc.) Better yet, don't do any authentication or authorization based solely on hostname or even on IP address; there is no way to be sure that a packet comes from the IP address it claims to come from, unless some kind of cryptographic authentication is within the packet that only the true source could have generated.

Some implementations of double-reverse lookup fail on hosts with multiple addresses, (e.g., dual-homed hosts used for proxying). If both addresses are registered at the same name, a DNS lookup by name will return both of them, but many programs will read only the first. If the connection happened to come from the second address, the double-reverse will incorrectly fail even though the host is correctly registered. Although you should avoid using double-reverse implementations that have this flaw, you may also want to ensure that on your externally visible multi-homed hosts, lookup by address returns a different name for each address, and that those names have only one address returned when it is looked up. For example, for a host named "foo" with two interfaces named "e0" and "e1", have lookups of "foo" return both addresses, lookups of "foo-e0" and "foo-e1" return only the address of that interface, and lookups by IP address return "foo-e0" or "foo-e1" (but not simply "foo") as appropriate.

It's very convenient for clients to be able to update DNS servers. For instance, at sites that use DHCP to dynamically assign addresses to computers, dynamic updates allow clients to have consistent names. When a client gets an address from DHCP, it can then register that address with the name server under the client's usual name. There is a standard for dynamic updates of DNS, but it isn't very widely used because it provides no kind of authentication. Some servers do provide authentication methods for dynamic updates (for instance, Windows 2000 allows you to integrate DNS with Active Directory and use Kerberos to authenticate update requests), but there is no widespread and interoperable standard for this.

Without authentication, dynamic update of DNS is extremely risky. You can't keep hostile clients from stealing addresses from each other or swamping the server in changes. Therefore, dynamic updates in DNS can be used only inside networks where there is a very high degree of trust.

Another problem you may encounter when supporting DNS with a firewall is that it may reveal information that you don't want revealed. Some organizations view internal hostnames (as well as other information about internal hosts) as confidential information. They want to protect these hostnames much as they do their internal telephone directories. They're nervous because internal hostnames may reveal project names or other product intelligence, or because these names may reveal the type of the hosts (which may make an attack easier). For example, it's easy to guess what kind of system something is if its name is "lab-sun" or "cisco-gw".

Even the simplest hostname information can be helpful to an attacker who wants to bluff his or her way into your site, physically or electronically. Using information in this way is an example of what is commonly called a social engineering attack. The attacker first examines the DNS data to determine the name of a key host or hosts at your site. Such hosts will often be listed as DNS servers for the domain or as MX gateways for lots of other hosts. Next, the attacker calls or visits your site, posing as a service technician, and claims to need to work on these hosts. The attacker will then ask for the passwords for the hosts (on the telephone) or ask to be shown to the machine room (in person). Because the attacker seems legitimate and seems to have inside information about the site — after all, the machine names are right — people will often grant access. Social engineering attacks like this takes a lot of brazenness on the part of the attacker, particularly if they're carried out in person, but you'd be amazed at how often such attacks succeed.

Besides internal hostnames, other information is often placed within the DNS—information that is useful locally but you'd really rather an attacker not have access to. DNS HINFO and TXT resource records are particularly revealing:

- HINFO (host information records)

These name the hardware and operating system release that a machine is running: it's very useful information for system and network administrators but also tells an attacker exactly which list of bugs to try on that machine.

- TXT (textual information records)

These are essentially short unformatted text records used by a variety of different services to provide various information. For example, some versions of Kerberos and related tools use these records to store information that, at another site, might be handled by NIS.

Attackers will often obtain DNS information about your site wholesale by contacting your DNS server and asking for a zone transfer, as if they were a secondary server for your site. You can prevent this either with packet filtering (by blocking TCP-based DNS queries, which will block more than just zone transfers) or by configuring your DNS server to control which hosts it is willing to do zone transfers to (although it will use the IP address to validate hosts and will be vulnerable to IP spoofing). The various versions of BIND control this in different ways (consult your BIND documentation for more information), while the Microsoft DNS server allows you to specify that only hosts that receive notifications may do zone transfers.

The question to keep in mind when considering what DNS data to reveal is, "Why give attackers any more information than necessary?" The following sections provide some suggestions to help you reveal only the data you want people to have.

We've mentioned that DNS has a query-forwarding capability. By taking advantage of this capability, you can give internal hosts an unrestricted view of both internal and external DNS data, while restricting external hosts to a very limited ("sanitized") view of internal DNS data. You might want to do this for such reasons as the following:

Your internal DNS data is too sensitive to show to everybody.

You know that your internal DNS servers don't all work perfectly, and you want a better-maintained view for the outside world.

You want to give certain information to external hosts and different information to internal hosts (for example, you want internal hosts to send mail directly to internal machines but external hosts to see an MX record directing the mail to a bastion host).

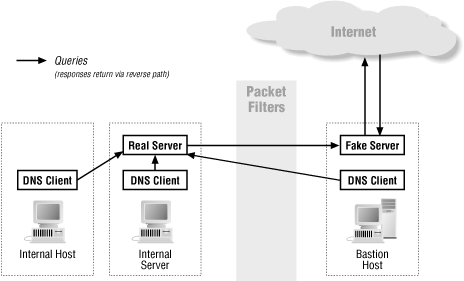

Figure 20.3 shows one way to set up DNS to hide information; the following sections describe all the details. This mechanism will work only for sites that use a single domain (all hosts are named something like host.foo.example, rather than host.sillywalks.foo.example and host.engineering.foo.example). If you have subdomains, you will need a more complicated configuration, which we discuss in the next section.

The first step in hiding DNS information from the external world is to set up a fake DNS server on a bastion host. This server claims to be authoritative for your domain. Make it the server for your domain that is named by the NS records maintained by your parent domain. If you have multiple such servers for the outside world to talk to (which you should — some or all of the rest may belong to your service provider), make your fake server the primary server of the set of authoritative servers; make the others secondaries of this primary server.

As far as this fake server on the bastion host is aware, it knows everything about your domain. In fact, though, all it knows about is whatever information you want revealed to the outside world. This information typically includes only basic hostname and IP address information about the following hosts:

The machines on your perimeter network (i.e., the machines that make up your firewall).

Any machines that somebody in the outside world needs to be able to contact directly. One example of such a machine is an internal Usenet news (NNTP) server that is reachable from your service provider. (See the section on NNTP in Chapter 16, for an example of why you might want to allow this.) Another example is any host reachable over the Internet from trusted affiliates. External machines need an externally visible name for such an internal machine; it need not be the internal machine's real name, however, if you feel that the real name is somehow sensitive information, or you just want to be able to change it on a whim.

In addition, you'll need to publish MX records for any host or domain names that are used as part of addresses in electronic mail messages and Usenet news postings, so that people can reply to these messages. Keep in mind that people may reply to messages days, weeks, months, or even years after they were sent. If a given host or domain name has been widely used as part of an electronic mail address, you may need to preserve an MX record for that host or domain forever, or at least until well after it's dead and gone, so that people can still reply to old messages. If it has appeared in print, "forever" may be all too accurate; sites still receive electronic mail for machines decommissioned five and ten years ago.

You can create a wildcard MX record that redirects mail for any hostname that there is no other record for. It looks like a normal MX record for a host named "*". However, you should be aware that wildcard MX records do not apply to names that have other records of their own. Any host that has an A record will require an individual MX record, even if there is a wildcard MX record; the same holds true for names of subdomains that have NS records.

You will also need to publish fake information for any machines that can contact the outside world directly. Many servers on the Internet (for example, most major anonymous FTP servers) insist on knowing the hostname (not just the IP address) of any machines that contact them, even if they do nothing with the hostname but log it. In the DNS resource records, A (name-to-address mapping) records and PTR (address-to-name mapping) records handle lookups for names and addresses.

As we've mentioned earlier, machines that have IP addresses and need hostnames do reverse lookups. With a reverse lookup, the server starts with the remote IP address of the incoming connection and looks up the hostname that the connection is coming from. It takes the IP address (for example, 172.16.19.67), permutes it in a particular way (reverses the parts and adds .IN-ADDR.ARPA to get 67.19.16.172.IN-ADDR.ARPA), and looks up a PTR record for that name. The PTR record should return the hostname for the host with that address (e.g., mycroft.somewhere.example), which the server then uses for its logs or whatever.

How can you deal with these reverse lookups? If all these servers wanted was a name to log, you could simply create a wildcard PTR record. That record would indicate that a whole range of addresses belongs to an unknown host in a particular domain. For example, you might have a lookup for *.19.16.172.IN-ADDR.ARPA return unknown.somewhere.example. Returning this information would be fairly helpful; it would at least tell the server administrator whose machine it was (somewhere.example 's). Anyone who had a problem with the machine could pursue it through the published contacts for the somewhere.example domain.

There is a problem with doing only this, however. In an effort to validate the data returned by the DNS, more and more servers (particularly anonymous FTP servers) are now doing a double-reverse lookup and won't talk to you unless the double-reverse lookup succeeds. It is the same kind of lookup we mentioned previously; it's certainly necessary for people who provide a service where they use IP addresses to authenticate requests. Whether or not anonymous FTP is such a service is another question. Some people believe that once you put a file up for anonymous FTP, you no longer have reason to try to authenticate hosts; after all, you're trying to give information away. People running anonymous FTP servers that do double-reverse lookup argue that people who want services have a responsibility to be members of the network community and that requires being identifiable. Whichever side of the argument you're on, it is certainly true that the maintainers of several of the largest and best-known anonymous FTP servers are on the side that favors double-reverse lookup and will not provide service to you unless double-reverse lookup succeeds.

In a double-reverse lookup, a DNS client:

Performs a reverse lookup to translate an IP address to a hostname

Does a regular lookup on that hostname to determine its nominal IP address

Compares this nominal IP address to the original IP address

The regular lookup can return different information from the original IP address in several situations. As we've discussed, they may return different information for legitimate reasons (the host is multi-homed or is using a wildcard PTR record) or because an attacker has provided illegitimate cached data. They may also be different if the attacker legitimately controls the name server with the PTR data in it but is returning other people's hostnames in the hope that services will use the results without checking them.

In order to make double-reverse lookups work, your fake server needs to provide consistent fake data for all hosts in your domain whose IP addresses are going to be seen by the outside world. For every IP address you own, the fake server must publish a PTR record with a fake hostname, as well as a corresponding A record that maps the fake hostname back to the IP address. For example, for the address 172.16.1.2, you might publish a PTR record with the name host-172-16-1-2.somewhere.example and a corresponding A record that maps host-172-16-1-2.somewhere.example back to the corresponding IP address (172.16.1.2). When you connect to some remote system that attempts to do a reverse lookup of your IP address (e.g., 172.16.1.2) to determine your hostname, that system will get back the fake hostname (e.g., host-172-16-1-2). If the system then attempts to do a double-reverse lookup to translate that hostname to an IP address, it will get back 172.16.1.2, which matches the original IP address and satisfies the consistency check.

If you are strictly using proxying to connect internal hosts to the external world, you don't need to set up the fake information for your internal hosts; you simply need to put up information for the host or hosts running the proxy server. The external world will see only the proxy server's address. For a large network, this by itself may make using proxy service for FTP worthwhile.

Your internal machines need to use the real DNS information about your hosts, not the fake information presented to the outside world. You do this through a standard DNS server setup on some internal system. Your internal machines may also want to find out about external machines, though (e.g., to translate the hostname of a remote anonymous FTP site to an IP address).

One way to accomplish this is to provide access to external DNS information by configuring your internal DNS server to query remote DNS servers directly, as appropriate, to resolve queries from internal clients about external hosts. Such a configuration, however, would require opening your packet filtering to allow your internal DNS server to talk to these remote DNS servers (which might be on any host on the Internet). This is a problem because DNS is UDP-based, and as we discuss in Chapter 8, you need to block UDP altogether in order to block outside access to vulnerable RPC-based services like NFS and NIS.

Fortunately, the most common DNS server (the Unix named program) provides a solution to this dilemma: the forwarders directive in the /etc/named.boot server configuration file. The forwarders directive tells the server that, if it doesn't know the information itself already (either from its own zone information or from its cache), it should forward the query to a specific server and let this other server figure out the answer, rather than try to contact servers all over the Internet in an attempt to determine the answer itself. In the /etc/named.boot configuration file, you set up the forwarders line to point to the fake server on the bastion host; the file also needs to contain a "slave" line to tell it to use only the servers on the forwarders line, even if the forwarders are slow in answering.

The use of the forwarders mechanism doesn't really have anything to do with hiding the information in the internal DNS server; it has everything to do with making the packet filtering as strict as possible (i.e., applying the principle of least privilege), by making it so that the internal DNS server can talk only to the bastion host DNS server, not to DNS servers throughout the whole Internet.

If internal hosts can't contact external hosts, you may not want to bother setting things up so that they can resolve external hostnames. SOCKS proxy clients can be set up to use the external name server directly. This simplifies your name service configuration somewhat, but it complicates your proxying configuration, and some users may want to resolve hostnames even though they can't reach them (for example, they may be interested in knowing whether the hostname in an electronic mail address is valid).

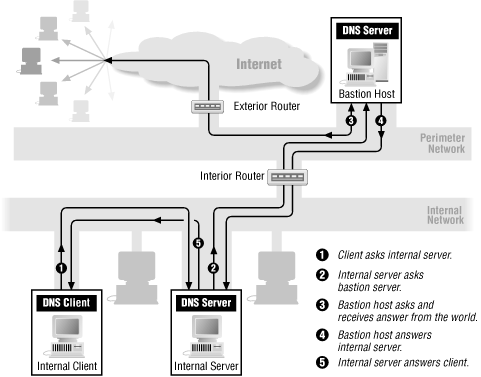

Figure 20.4 shows how DNS works with forwarding; Figure 20.5 shows how it works without forwarding.

The next step is to configure your internal DNS clients to ask all their queries of the internal server. On Unix systems, you do this through the resolv.conf file.[15] There are two cases:

When the internal server receives a query about an internal system, or about an external system that is in its cache, it answers directly and immediately because it already knows the answers to such queries.

When the internal server receives a query about an external system that isn't in its cache, the internal server forwards this query to the bastion host server (because of the forwarders line described previously). The bastion host server obtains the answer from the appropriate DNS servers on the Internet and relays the answer back to the internal server. The internal server then answers the original client and caches the answer.

In either case, as far as the client is concerned, it asked a question of the internal server and got an answer from the internal server. The client doesn't know whether the internal server already knew the answer or had to obtain the answer from other servers (indirectly, via the bastion server). Therefore, the resolv.conf file will look perfectly standard on internal clients.

In this arrangement special care is needed when configuring internal SMTP servers. Because such services have access to address information, they may try to deliver mail directly rather than through your mail gateway.

The key to this whole information-hiding configuration is that DNS clients on the bastion host must query the internal server for information, not the server on the bastion host. This way, DNS clients on the bastion host (such as Sendmail, for example) can use the real hostnames and so on for internal hosts, but clients in the outside world can't access the internal data.

DNS server and client configurations are completely separate. Many people assume that they must have configuration files in common, that the clients will automatically know about the local server, and that pointing them elsewhere will also point the server elsewhere. In fact, there is no overlap. Clients never read /etc/named.boot, which tells the server what to do, and the server never reads /etc/resolv.conf, which tells the clients what to do.

Again, there are two cases:

When a DNS client on the bastion host asks about an internal system, it gets the real answer directly from the internal server.

When a DNS client on the bastion host asks about an external system, the internal DNS server forwards the query to the bastion DNS server. The bastion server obtains the answer from the appropriate DNS servers on the Internet and then relays the answer back to the internal server. The internal server, in turn, answers the original client on the bastion host.

DNS clients on the bastion host could obtain information about external hosts more directly by asking the DNS server on the bastion host instead of the one on the internal host. However, if they did that, they'd be unable to get the "real" internal information, which only the server on the internal host has. They're going to need that information because they're talking to the internal hosts as well as the external hosts.

Since it is possible to configure a DNS client with multiple server names, it is tempting to configure DNS clients on the bastion host to query both the internal and the external server, in the hope that they will try one and then try the other if the first one returns "host unknown". In fact, this will not work; a DNS client will try a second server only if the first one does not respond. It will accept "host unknown" as a valid answer.

In order for this DNS forwarding scheme to work, any packet filtering system between the bastion host and the internal systems has to allow all of the following (see the table for details):

DNS queries from the internal server to the bastion host server: UDP packets from port 53 or ports above 1023 on the internal server to port 53 on the bastion host (rule A), and TCP packets from ports above 1023 on the internal server to port 53 on the bastion host (rule B)

Responses to those queries from the bastion host to the internal server: UDP packets from port 53 on the bastion host to port 53 or ports above 1023 on the internal server (rule C), and TCP packets with the ACK bit set from port 53 on the bastion host to ports above 1023 on the internal server (rule D)

DNS queries from the bastion host DNS clients to the internal server: UDP and TCP packets from ports above 1023 on the bastion host to port 53 on the internal server (rules E and F)

Responses from the internal server to those bastion host DNS clients: UDP packets, as well as TCP packets with the ACK bit set, from port 53 on the internal server to ports above 1023 on the bastion host (Rules G and H)

Rule | Direction | Source Addr. | Dest. Addr. | Protocol | SourcePort | Dest.Port | ACKSet | Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A | Out | Internal server | Bastion host | UDP | 53, >1023 | 53 | [16] | Permit |

B | Out | Internal server | Bastion host | TCP | >1023 | 53 | Any | Permit |

C | In | Bastion host | Internal server | UDP | 53 | 53, >1023 | [16] | Permit |

D | In | Bastion host | Internal server | TCP | 53 | >1023 | Yes | Permit |

E | In | Bastion host | Internal server | UDP | >1023 | 53 | [16] | Permit |

F | In | Bastion host | Internal server | TCP | >1023 | 53 | Any | Permit |

G | Out | Internal server | Bastion host | UDP | 53 | >1023 | [16] | Permit |

H | Out | Internal server | Bastion host | TCP | 53 | >1023 | Yes | Permit |

[16] UDP has no ACK equivalent. | ||||||||

If your site has subdomains, you cannot simply set up a server for each subdomain and have it forward queries to a bastion host that has only external information. If you do this, a host in one subdomain will not be able to get information on hosts in other subdomains. When host.sillywalks.foo.example queries for host.engineering.foo.example, the name server for sillywalks.foo.example will notice that it does not have the information and will forward the query to the bastion host, which does not contain internal information and will not be able to respond to the query.

There are a number of solutions to this problem, which are discussed in detail in DNS and BIND, by Paul Albitz and Cricket Liu, referenced earlier in this chapter. None of them are perfect. One option is to set up every server so that it knows about every subdomain; this removes many of the advantages of having the subdomains in the first place. Another is to set up the bastion host so that it has correct internal information but refuses to give it out to external queriers (you use the secure_zones directive for this). This removes much of the security of having a separate bastion host name server.

You can also avoid the problem by avoiding query forwarding. If there is no forwarding, normal resolution will take place, and all of the subdomains will work. On the other hand, internal machines will not be able to resolve external hostnames to IP addresses and will need to have carefully configured proxying solutions to reach external hosts.

The approach we've described in the previous section is not the only option. Suppose that you don't feel it's necessary to hide your internal DNS data from the world. In this case, your DNS configuration is similar to the one we've described previously, but it's somewhat simpler. Figure 20.6 shows how DNS works without information hiding.

With this alternate approach, you should still have a bastion host DNS server and an internal DNS server; however, one of these can be a secondary server of the other. Generally, it's easier to make the bastion DNS server a secondary of the internal DNS server and to maintain your DNS data on the internal server. You should still configure the internal DNS server to forward queries to the bastion host DNS server, but the bastion host DNS clients can be configured to query the bastion host server instead of the internal server.

You need to configure any packet filtering system between the bastion host and the internal server to allow the following (see the table for details):

DNS queries from the internal DNS server to the bastion DNS server: UDP packets from port 53 or ports above 1023 on the internal server to port 53 on the bastion host (rule A), and TCP packets from ports above 1023 on the internal server to port 53 on the bastion host (rule B)

Responses from the bastion DNS server to the internal DNS server: UDP packets from port 53 on the bastion host to port 53 or ports above 1023 on the internal server (rule C), and TCP packets with the ACK bit set from port 53 on the bastion host to ports above 1023 on the internal server (rule D)

If the bastion host is also a DNS secondary server and the internal host is the corresponding DNS primary server, you also have to allow the following:

DNS queries from the bastion host DNS server to the internal DNS server: UDP packets from port 53 or ports above 1023 on the bastion host to port 53 on the internal server (rule E), and TCP packets from ports above 1023 on the bastion host to port 53 on the internal server (rule F)

Responses from the internal DNS server back to the bastion DNS server: UDP packets from port 53 or ports above 1023 on the internal server to port 53 or ports above 1023 on the bastion host (rule G), and TCP packets with the ACK bit set from port 53 on the internal server to ports above 1023 on the bastion host (rule H)

DNS zone transfer requests from the bastion host to the internal server: TCP packets from ports above 1023 on the bastion host to port 53 on the internal server (note that this is the same as rule F)

DNS zone transfer responses from the internal server to the bastion host: TCP packets with the ACK bit set from port 53 on the internal server to ports above 1023 on the bastion host (note that this is the same as rule H)

Rule | Direction | Source Addr. | Dest. Addr. | Protocol | SourcePort | Dest.Port | ACKSet | Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A | Out | Internal server | Bastion host | UDP | 53, >1023 | 53 | [20] | Permit |

B | Out | Internal server | Bastion host | TCP | >1023 | 53 | Any | Permit |

C | In | Bastion host | Internal server | UDP | 53 | 53, >1023 | [20] | Permit |

D | In | Bastion host | Internal server | TCP | 53 | >1023 | Yes | Permit |

E | In | Bastion host | Internal server | UDP | 53, >1023 | 53 | [20] | Permit |

F | In | Bastion host | Internal server | TCP | >1023 | 53 | Any | Permit |

G | Out | Internal server | Bastion host | UDP | 53 | 53, >1023 | [20] | Permit |

H | Out | Internal server | Bastion host | TCP | 53 | >1023 | Yes | Permit |

[20] UDP has no ACK equivalent. | ||||||||

Windows 2000 uses DNS extensively; it is the primary method for name resolution, replacing Windows native modes of name resolution, which are supported only for older clients. Windows 2000 requires some DNS extensions that currently are in the standards process but are not yet accepted or widely used.

In particular, Windows 2000 consistently uses names that contain underscores. Traditionally, DNS names have been allowed to contain only letters, numbers, or hyphens (-). The underscore ( _ ) has been forbidden by the standard. In practice, most name servers did not enforce these name restrictions. Although the underscore has been theoretically forbidden for many years, name servers that do not allow underscores became popular fairly late in the development of Windows 2000. At about the same time, a push to loosen the restrictions on allowable names began. This situation has not been resolved as of this writing; a standard under discussion would allow almost any character in a DNS name, but it has not yet been accepted. In the meantime, some servers enforce strict name rules and reject names with underscores; some servers follow tradition and accept almost any ASCII character; and some servers accept even more characters, including those outside the ASCII range (for instance, accented letters). Windows 2000 minimally requires a DNS server that will allow underscores. Windows 2000 allows machine names that use other characters outside the normally permitted types, and those names may create mysterious failures unless you use a DNS server that accepts them.

Windows 2000 also uses a record type, the SRV record, which has not yet been standardized. A number of DNS servers support SRV, including versions of BIND starting with 4.9.6 (and all versions of BIND 8).

Windows 2000 relies on the ability to do dynamic updates of DNS information. When machines boot, they need to be able to register names in the DNS server. Dynamic updates are supported by BIND 8 but not with the authentication mechanisms used by Windows 2000. Using BIND 8 to support Windows 2000 therefore requires using unsecured dynamic updates.

Windows 2000 DNS can use Active Directory as a storage and replication method. In this configuration, the DNS information is stored in Active Directory, and DNS is simply used as a method of accessing it. A DNS server that is integrated with Active Directory must be a primary server; it can send updates to other DNS servers via normal zone transfers but cannot accept them because it is not controlling the data. However, when Windows 2000 DNS is integrated with Active Directory, it supports secure dynamic update using Kerberos for authentication.

There is no particular difficulty using network address translation with a DNS client that is having its address translated; the client's address is not embedded in the DNS transaction. Putting a DNS server behind an address translator is a different proposition. If the data in the server is about machines that are also behind the address translator, the address translator will need to operate on the data inside the DNS packets, not just on the source and destination addresses. Otherwise, the server will be handing out useless information. Some network address translation systems are capable of doing this, although some of them will translate only responses to queries, not zone transfers.

Set up an external DNS server on a bastion host for the outside world to access.

Do not make HINFO records visible to the outside world; either don't use them, or configure DNS for information hiding as described earlier.

Use an up-to-date BIND implementation and double-reverse lookups to avoid spoofing.

Consider hiding all internal DNS data and using forwarding and fake records; this doesn't make sense for all sites, but it might for yours.

Disable zone transfers to anyone but your secondaries, using packet filtering or the mechanism supported by your DNS server. Even if you've chosen not to hide your DNS information, there's probably no valid reason for anyone but your secondaries to do a zone transfer, and disallowing zone transfers makes life a bit harder for attackers.

[1] On some types of failures, some servers will cache the fact that the query failed. Others cache only information retrieved on a successful query.

[14] For detailed information about DNS record types, what they mean, and how to use them, see the DNS and BIND book, referenced earlier in this chapter.

[15] These days, clients may also keep DNS configuration information elsewhere—for instance, under IRIX 6.5 and above, DNS configuration parameters can also be put in the nsswitch file that will override the equivalent parameters in resolv.conf.