Figure 15.1 Tak Baad, the morning alms-giving ritual in the course of which locals offer food to their monks is a metaphor of cultural loss for many heritage experts, expatriates and Lao elites (Photo S. Malaidet)

15

The Politics of Loss and Nostalgia in Luang Prabang (Lao PDR)

Introduction

For anthropologists interested in issues of cultural heritage, Luang Prabang, an ancient royal town of Northern Laos which became a UNESCO Listed World Heritage site in 1995, constitutes a fascinating example of ever-growing touristification, complex coexistence of Buddhist religion and politics of material conservation and gay sexscape with masculine prostitution on the rise (Berliner 2011). However, among the manifold changes occurring in this former colonial place, it is also a town where material preservation of ordinary and religious architecture has become a political and moral obligation, and nostalgia serves as a motto as well as a resource for preservation agents, private investors and tourist companies. Grant Evans (1998) and, later on, Colin Long and Jonathan Sweet have cogently emphasised how Luang Prabang’s UNESCO recognition is rooted in nostalgic imagination, ‘a quest for an Idealized, Orientalized “real Asia”’ (Long and Sweet 2006: 455). My anthropological research delves further into the very fabric of nostalgia in Luang Prabang, its multiple agents, words, contexts and objects. In the following pages, I will describe a complex landscape where ideas and feelings of preservation, transmission and loss are being differently displayed by diverse categories of actors, local elites, expatriates, Asian and Western tourists, UNESCO experts, Buddhist monks and inhabitants, who all occupy diverse positions within such an arena. A disappearing vestige of humanity for developers, an Indochinese Oxford for Western tourists, a damned town for some of its inhabitants, a great place to invest in for others, a religious centre for Lao and Thai visitors and so forth, Luang Prabang represents a hybrid which deploys an intricate scene under our anthropologists’ eyes. In that regard, it shows how such heritagescapes, caught in the dilemmas of modernity, tourism and nostalgia, can be variously experienced and contested by different groups of often disconnected people. However, while engaging with the Luang Prabang of their own, with their own agendas and influences, they still produce a heritage scene together.

The Politics of Loss and Nostalgia

Nostalgia, in the sense of a ‘longing for what is lacking in a changed present (…) a yearning for what is now unattainable, simply because of the irreversibility of time’ (Pickering and Keightley 2006: 920), is a central notion that permeates many contemporary discourses and practices (Boym 2001). We live in a time when many people lament the disappearance of forms of life, customs, languages, cultures, skills, natural sites and values from the past, disappearances that most have never experienced themselves. Such ‘armchair nostalgia’ (Appadurai 1996: 78) manifests itself through the attachment of Western tourists and heritage experts to other people’s cultural loss (especially in postcolonial worlds, for which using Rosaldo’s notion of ‘imperialist nostalgia’ (1989) is also pertinent). Indeed, the trope of the vanishing, key of many tourist attractions (Dann 1998, Graburn 1995), is at the core of contemporary preservation policies philosophy. UNESCO, although its perspectives are much more fragmented than one might expect (between different delegations and regional offices, for instance), significantly contributes to the dissemination of such nostalgic views about cultural loss around the world, practically defining what is worth being preserved and transmitted (a natural site, a monument, a cultural practice, an object), how it should be done (actors, groups, institutions) and why (UNESCO experts stating what preservation and transmission are).1

In this chapter, I suggest that Luang Prabang is an arena of nostalgias. First, I shall describe the transformation of the town into the ‘nostalgiascape’ it is today. To better understand a yearning for the past resulting in consumption, Szilvia Gyimothy defines the term ‘nostalgiascape’ by its effects, i.e., ‘if visitors develop an emotional or cognitive attachment to the place, era or people within the topical context’ (Gyimothy 2005: 113). Looking at ‘inns’ in Denmark, she shows how these accommodations in the countryside constitute nostalgiascapes which activate romantic and patriotic memories of rural Danishness. A similar issue is tackled by Maurizio Peleggi (2005) who examines the consumption of colonial nostalgia in Southeast Asia through the renovation of colonial-era grand hotels for tourists, as well as by Tianshu Pan, a Chinese anthropologist who witnessed the emergence of an elite-driven pre-1949 nostalgia in Shangai, a tourism-oriented nostalgia for colonial architecture ‘hardly relevant to the everyday life of ordinary people’ (Pan 2007: 29). In the case of Luang Prabang, I propose that it is necessary to expand such notions beyond consumerism to describe whose nostalgia is being displayed; the convergence of discourses about heritage, loss and vanishing into nostalgic actions on the ground; and the diverse mediations (institutions, agents and objects) that allow such processes. Some discourses about longing speak louder than others, but this should not make us forget the plurality of nostalgic claims and forms. Following Cunningham Bissel’s excellent study in Zanzibar, I urge that, in Luang Prabang, one tries to locate ‘the multiple strands of nostalgia circulating’ (2005: 235), some of which ‘reconstruct the past as a means of establishing a point of critique in the present’ (ibid.: 239). Whilst ethnographies of nostalgia and loss are scarce, I see this chapter as a contribution to a more insightful understanding of how these notions and actions are deployed by the agents who participate, deliberately or not, in turning Luang Prabang into such a heritagescape.

The UNESCO-Isation of Luang Prabang

Famous for its thirty-four Buddhist monasteries and orange-robed monks, as well as for its colonial architecture, Luang Prabang is an ancient royal town (Stuart-Fox 1997). Its history is punctuated by the succession of kings from the fourteenth century when King Fa Ngum established Lane Xang Kingdom on the territory occupied by Khmu people (one of the ethnic groups of Laos) and, accepting a golden statue of the Buddha, adopted Theravada Buddhism. From the fifteenth century, Luang Prabang has seen successive invasions by foreign powers: the Vietnamese, the Burmese, the Siamese, the Chinese Haw and, finally, the French who, after having signed an agreement with the reigning king, invented the national borders of Laos and established a Protectorate which persisted until 1953 (Ivarsson 2008). In the 1950s and 1960s, the development of the Lao People’s Revolutionary Party lead to the 1975 socialist revolution (and the dethronement of King Sisavangvatthana) which forced into exile many town residents who were regarded as possible supporters of the king. In 1995, after a long decision-making process involving Lao and French actors, the UNESCO assembly inscribed Luang Prabang on its World Heritage List at the Berlin Conference. Under the UNESCO umbrella, there is, in fact, a multiplicity of institutional agents who launched and still participate in the preservation project. They range from experts based in Paris and in Bangkok as well as to architects, engineers, cultural and tourism consultants based in Luang Prabang who are not UNESCO employees as such, but are funded by international organisations such as Agence Française du Développement, the European Union or the Asian Bank for Development and operate in close relationships with UNESCO. The ties between French preservation institutions and Luang Prabang officials are strong.2 Continuous technical and financial support flows from France, fostering a certain style of cultural preservation ‘à la Française’ centred on monumental material heritage and captured by some inhabitants when they described Luang Prabang to me as becoming ‘Luang Paris’.

Conservation policies mainly focus on the inventory of traditional and colonial houses (611 houses are listed), temples and natural and aquatic spaces. These protected areas are carefully monitored via the Maison du Patrimoine (Heritage House), a Lao institution composed of a mixture of Lao architects and foreign experts (mostly French) through which UNESCO-Paris preservation policies are implemented. Heritage House aims to ensure that the Luang Prabang conservation plan, established in 2000 by French UNESCO architects, is followed. For instance, among many other tasks, it monitors the over-densification of urban space and denounces new illegal building activities within the protected perimeter, as well as inappropriate use of architectural forms and materials (height, painting, light, windows, fences); it protects listed houses from demolition as well as wetlands, vegetation cover, river banks and trees; and it seeks to regulate rampant economic activities by foreign investors who rent many downtown houses and transform them into guesthouses and restaurants. Above all, Heritage House strives to preserve and restore pre-WWII religious and ordinary listed monuments in the town. By contrast, the UNESCO office based in Bangkok has launched its own conservation projects, putting a clear emphasis on ‘intangible heritage’ preservation, such as sculpture classes for monks to learn to restore their temples themselves (IMPACT 2004).

Losing the Spirit of the Place

Although UNESCO-Paris and UNESCO-Bangkok experts and those based in Luang Prabang hold different perspectives on the modalities of preservation, most of them are nevertheless animated by the same spirit. Besides the diversity of perceptions and conservation projects, their common objective is to preserve the authenticity and the outstanding value of the site. For them, Luang Prabang appears as a very fragile site, threatened by the assault of Asian and European tourism and growing neo-liberal consumerism and in need of being urgently preserved from annihilation. They all use very nostalgic tropes to describe how until recently the town was one of the last remnants of local culture and now is losing much of its character. In their words, Luang Prabang represents this romantic quest for tradition and sincerity, a modernist pursuit for the ‘genuine thing’, with a certain fear of the artifices of modernity and globalising forces. For instance, in the brochure IMPACT edited by UNESCO-Bangkok in 2004, one can find the picture of a car parked in a temple with the caption: ‘Today temples are sometimes not treated with the respect they were given in the past’, the car being the symbol of modernity in a traditional temple. A UNESCO consultant met in Luang Prabang insisted that ‘The town has changed a lot over the last ten years. Soon the town-centre will be emptied of its inhabitants. Locals sell their houses and go in the suburbs. The monks also leave the town. Here it is like Disneyland now. It’s a disaster!’ For another expert who speaks with bitterness, it is already ‘too late. Luang Prabang is a failure’.

This idealised Luang Prabang is indeed a town of the days bygone. Many locals let their houses located in the centre of the town to foreign investors and they happily build large houses in the suburbs. Thirty-nine hotels, more than 190 guesthouses and a night market for tourists have opened up, whilst sixty-nine restaurants blossom along the Mekong and the Namkhan Rivers, such urban growth violating many of the heritage regulations. Indeed, against UNESCO rules, some town-centre residents fill their land with as much construction as they can (for instance, when building a guesthouse) while, in recent years, local authorities have rented out listed state buildings to foreign investors. Everyday, hundreds of tourists stroll in the old town, transforming Tak Baad, the morning alms-giving ritual during which inhabitants give food to their monks (who will in exchange pray and get merits for them), into a ‘circus’, ‘a zoo where tourists feed monks like they would feed animals’, says another foreign heritage expert (Figure 15.1). Accordingly, what is at the heart of most experts’ bitterness is the current vanishing of Luang Prabang ‘ambiance’, ‘atmosphere’ or ‘spirit of the place (genius loci)’. As one of my UNESCO interlocutors in Bangkok put it with a tone of cultural necrology, ‘Luang Prabang is under lots of pressure now. The whole town is being used by tourists only. Even the monks leave the town. We are losing the spirit of the place.’ Since the 2008 ICOMOS conference in Québec where the participants adopted a declaration of principles and recommendations to safeguard it, ‘l’esprit du lieu’ has become a crucial concept in UNESCO preservation policies, a notion defined ‘as the physical and the spiritual elements that give meaning, value, emotion and mystery to place (…) made up of tangible (sites, buildings, landscapes, routes, objects) as well as intangible elements (memories, narratives, written documents, festivals, commemorations, rituals, traditional knowledge, values, textures, colours, odours, etc.)’ (ICOMOS 2008). In terms of cultural heritage policies, it sounds like a fuzzy notion and one wonders how it can be monitored. Above all, this concept reminds me of the ‘charme nostalgique’ captured by the French philosopher Vladimir Jankélévitch as ‘ce je-ne-sais-quoi dont on ne peut assigner la place’ (‘this non-localisable I-do-not-know-what’) (Jankélévitch 1983: 303) which is even more precious now that it is said to disappear. In fact, interviews with foreign experts revealed the same set of underlying ideas about the spirit of Luang Prabang: A Western romanticised perception of Buddhism and colonial conceptions of other people’s traditional life, conveying nostalgia for local rituals (such as morning alms-giving), for a feeling of quietness (only disrupted by Buddhist gongs) and isolation under the Tropics and for autochthonous people living their traditional life in their traditional houses and temples.

Figure 15.1 Tak Baad, the morning alms-giving ritual in the course of which locals offer food to their monks is a metaphor of cultural loss for many heritage experts, expatriates and Lao elites (Photo S. Malaidet)

In order to ‘recreate the past atmosphere of Luang Prabang’ (as one foreign architect says) or to keep its sleepy ambiance, concrete preservation measures are adopted like, for instance, the restoration of temples and houses by using ancient material and techniques, the control of the electricity level and of commercial advertisements in town, or the transformation of old houses on stilts into cultural centres where traditional events or concerts are organised. One UNESCO-related architect suggested making a formal list of authorised offerings to the temples, so as to avoid the use of cement, acrylic paintings, industrial tiles and other modern construction materials nowadays offered by Luang Prabangese to their temples as a form of alms. Such anxieties about losing Luang Prabang’s atmosphere, whether it is tangible or intangible heritage, leads to very tangible decisions, with a recent verdict by the World Heritage Committee stating that Luang Prabang should ‘halt the progressive loss of its fabric and traditions in the face of development pressures’, warning Lao officials that ‘if the Lao traditional heritage in particular continues its steady decline, the town of Luang Prabang is heading towards a situation that would justify World Heritage in Danger listing’ (Boccardi and Logan 2007: 26).

All in all, these discourses and practices participate in the invention of a nostalgiascape in Luang Prabang, a nostalgic ‘heterotopia’ to use Foucault’s term (2009), a protected space where what one sees as the irreversible flow of time could, somehow, be controlled. Fashioning a world outside of the turbulences of the contemporary world, Luang Prabang’s centre looks neat and meticulously organised (like colonial Kinshasa, see de Boeck and Plissart 2004); a real space committed to organised arrangements of things, compensating for what many of us see today as a messy, globalised and disordered world. A real space not conserved as such but, in fact, a new territory re-invented by experts and local heritage officers.

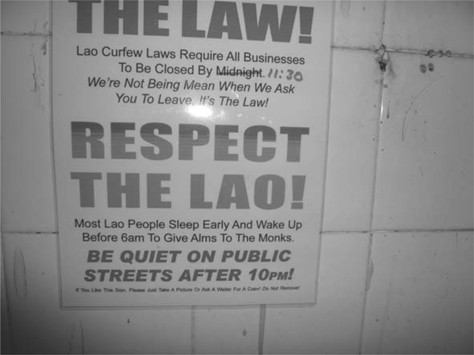

However, preserving the tranquil atmosphere and unique buildings are not only part of the UNESCO challenge. The sense of losing Luang Prabang culture is also shared, although with some differences, by some expatriates in the town as well as Lao elites and intellectuals who, after being exposed to ideas relating to the objectification of culture, have become intensely preoccupied with the preservation of the past. Interestingly, for most of them, Tak Baad has also become the metaphor of cultural loss itself, a lens through which they can efficiently describe changes which have had an effect on the town since its UNESCO recognition, with these ‘disgusting’ tourists who give alms to monks ‘just for fun and pictures, without knowing anything’. Many do indeed express concern about the morning alms-giving ritual as becoming a spectacle now ‘relying mostly on tourists and foreigners who live here, because local people have left the centre’, a tourist scene replacing the symbiotic relationship that has existed between monks and villagers for centuries. The fear of losing culture leads to concrete initiatives from Lao and expatriates like, among other examples, a cultural centre to preserve ‘the traditional arts and cultural heritage of Luang Prabang in their most authentic forms’ (run by a Lao who has lived in France for twenty years) or campaigns launched by expatriates to sensitise tourists to cultural issues concerning the alms-giving ritual (Figure 15.2). On the whole, all of these actions seal Luang Prabang’s fate as a town for cultural preservation and transmission.

Figure 15.2 Posters found in the restrooms of a restaurant to sensitise tourists to cultural issues concerning the alms-giving ritual (Photo A. Bernstein)

A Painless Nostalgiascape for Tourists

A heterotopia aimed at assuaging a fear of loss that many educated Westerners and Asians, whether they are experts or tourists, do share today, Luang Prabang has become a key destination for tourists in Southeast Asia. According to local statistics provided by the Tourism Office, it attracted 260,000 tourists in 2005, a boom in comparison with the 62,000 of 1997. While a contested heritagescape, Luang Prabang also constitutes an arena for diverse profiles of tourists with different agendas and influences, from French backpackers, Thai and Chinese tourists, expatriates living in Bangkok, Lao living abroad or in different provinces, British couples on honeymoon, or gay tourists, many of whom are not always driven by nostalgia (Caton and Santos 2007). Some young travellers, mostly Western backpackers, stop by Luang Prabang to relax and party after a trip ‘into the jungle’, whilst the town has also become a sexual heterotopia for numerous foreign men (Westerners or Asians alike) seeking to encounter Lao men. During the New Year festivals, many Lao from other provinces come visit Luang Prabang and perform their religious duties in some of the most famous Buddhist temples of Laos, whilst a great number of Lao exiles living abroad (in France, Australia, Germany or the USA) fly back to see members of their family who stayed in the country after 1975. For those who have experienced the suffering of exile, needless to say that Luang Prabang does not represent a painless heritagescape, but rather a trigger for pre-1975 nostalgic reminiscences and vivid memories of pain.

However, based upon my fieldwork, many tourists nevertheless see Luang Prabang as a charming little town set amongst lush mountains with its ‘amusing’ French influence and its Buddhist mystique. Many of the Westerners I have spoken with are enchanted with the ‘Indochina spirit’ of Luang Prabang, which plunges them into an idealised past world reminiscent of Marguerite Duras’ book L’Amant, the Indochina spirit with its old cars, fans, furniture and colours (Figure 15.3). They also enjoy approaching monks and chatting with them, an experience described as ‘charming’ and ‘full of respect’, which the monks easily turn to their own advantage by getting tourists’ addresses and, in many instances, gifts or cash. Many Western visitors emphasise the authenticity of the place, such as a French woman exclaiming to me that ‘here, it is the pure, real humanity’, whilst a British visitor described the town as ‘a sort of Indochinese Oxford’. However, they also lament the current vanishing of such authenticity, like the three Dutch persons in front of a temple regretting that locals ‘don’t wear traditional clothing anymore’ or an American woman who emphasised that seeing televisions in people’s homes made her realise how ‘people lose their traditions here’.

Figure 15.3 Hotel owners buy old cars to pick up tourists at the airport (Photo S. Malaidet)

Whilst most Westerners do lament the ongoing vanishing process of the town’s precious atmosphere (considering their visit as well-timed ‘before it disappears for ever’), Thai tourists massively throng to visit Luang Prabang to see ‘how Thailand was fifty or 100 years ago’ (one Thai lady says). A cheap destination, it represents for many Thai an assortment of fun (rafting speed boats on the Mekong), nostalgic curiosity and exoticism (observing so-called Lao backwardness and eating French baguette in restaurants) and religion (as they fervently give alms to the monks and offerings to famous Buddhas in town). Asian tourists do not experience the same yearning for the ‘Indochina spirit’ as the Westerners. Yet, Luang Prabang represents for them a picturesque old town preserved from urban craze. All in all, whether they fall for colonial nostalgia per se, exoticism or both, Luang Prabang constitutes for most tourists a site for nostalgic imagination, where the past is glorified, although served up in a sanitised manner with paved roads, clean guesthouses and tasty food. Such enchantment for the past is indeed constantly reinforced by tourist companies, restaurants and hotel owners (mostly foreigners, French, Thai, Vietnamese, Chinese, Singaporean but also Lao elites) who offer such nostalgia for the pre- WWII past as merchandise to be consumed by visitors, a posture defined by Peleggi as the ‘business of nostalgia’ (Peleggi 2002).

Needless to say that the past delivered to visitors preserves something, but it also deletes and distorts a lot else. For instance, nothing about the painful history of the town, the forced abdication of the king or the historical cooperation with Americans during the Vietnam war are explicit parts of the presented heritage of Luang Prabang. As one of my elderly interlocutors says, ‘Luang Prabang was a damned town for years after the Revolution. Then UNESCO comes and wants to make a nice town here. Tourists don’t know that. But we have suffered a lot here’. When walking in the streets of Luang Prabang and talking with its tourists, one can be reminded of this ‘past without the pain’ analysed by Laurel Kennedy and Mary Rose Williams where they describe how post-war Vietnam is now becoming a harmless tourist attraction (Kennedy and Williams 2001). Following what Long and Sweet have lucidly written, in Luang Prabang, ‘it appears that (…) colonialism has been nostalgically re-packaged as a benign interlude in Lao history, which simply helped produce some lovely architecture and which now frames some tasteful religious and craft practices’ (Long and Sweet 2006: 455). Indeed, through a very specific selection of monuments, in fact a patchwork made of pre-colonial and French colonial architectural traces only (a historical selection one can put into question), it is as if an ‘eternal phantasmatic Indochina’ (Norindr 1997) and French colonialism, defined as a quite harmonious integration of cultural traditions, were somehow celebrated.

‘We Want More Tourists and Planes Flying Here … ’

Whilst for some heritage experts, foreign tourists, expatriates and Lao elites, Luang Prabang symbolises a spirit to be urgently salvaged from the destructive assaults of rapid modernisation, most locals I interviewed do not identify with this. Are Laotians nostalgic of a past when ‘there was no traffic jam, little tourism and no television’? How do they experience the transformation of their town into a nostalgiascape? Do they identify with UNESCO policies defining preservation as a collective obligation? To answer these questions, I have conducted interviews with residents of the town-centre and residents of the suburbs (those who left the centre to settle down at the outskirts), guesthouses and restaurants owners, souvenir/ethnic handicraft shopkeepers, local intellectuals, political heads as well as Buddhist religious leaders and monks. Obviously, when it comes to heritage, there is a diversity of conceptions which are generational and divided along lines of education, but also depend on the benefits gained from tourism and heritage economy.

However, there are some common perceptions about moladok, the local word used to designate ‘heritage’ (most of my interlocutors never mention UNESCO as such). Moladok is not a new Lao word, as people use it to refer to familial heritage, mainly connoting ‘something which has to be kept and passed on between generations’. However, recently, it has acquired a whole new meaning, an idea conveyed by some interlocutors when they confess that ‘before UNESCO, we never heard about moladok’. For many people, these new meanings attached to moladok do not seem very apparent yet, besides its tourism and economic implications. Heritage-making policies are indeed top-down and external strategies implying for most inhabitants a kind of deference toward institutional authority and, as one interlocutor stated, ‘we do moladok because we respect the government’. However, beyond diversity, most residents emphasise how their life has positively changed over the last ten years. Many are proud to see that their town is now an internationally recognised site, where tourists come from all over the world and bring a lot of money. The increase of economic resources is the most often mentioned positive impact of UNESCO-isation, as it has created new job opportunities, albeit unequally, for many people in Luang Prabang and in the countryside (from guesthouses and rickshaw drivers to ethnic handicraft producers). Also, many highlight that renovations are rendering Luang Prabang more pretty and clean and that by helping refurbish temples, ‘moladok helps Buddhism’. In brief, ‘life is better here since moladok’ is a sentence I have heard hundreds of times during interviews and it makes sense after many years of a traumatic historic in Laos and in Luang Prabang in particular.

However, in casual interactions, people rarely speak about heritage. When they do so, it is mostly to denounce how heritage regulations are strict and recommendations difficult to follow, seen by some as ‘hell’ (‘moladok monahok’ in Lao). Indeed, Heritage House is mostly perceived as an institution which ‘forbids one of doing that or that’ and the feeling of being constrained is evoked in most conversations (‘moladok, it’s good, but we might not build as we want now’). Clearly, UNESCO policies have fostered a sense of losing property rights among inhabitants who feel that, according to one interlocutor, ‘moladok wants to limit our property rights. These lands are ours. Before moladok, we repaired houses the way we needed but now we have to ask for permission at Heritage House’. Even a religious leader (saa thu) who wants to erect new rooms in his temple against a Heritage House decision exclaimed to me: ‘This is our temple. We are entitled to do whatever we want here’. Moreover, to follow ‘moladok style’ is also constraining for certain architects who, from now on, cannot create new architectural forms, but have to follow architectural typologies and use materials imposed by UNESCO-related architects, creating a sense of architectural standardisation in the town-centre, denounced by some Lao elites and foreign expatriates (‘here it’s not a town for invention, but for preservation’).

In particular, the question of intactness in architectural preservation, an idea cherished by most the experts, seems to be a much contested one. To preserve the ancient as it was makes little sense to most of my interlocutors who have a rather practical conception of heritage. Holding an aesthetic competence denied by most foreign experts, many of them declare to be fond of renovated Lao traditional wooden houses (and also applaud temple renovations). However, they display a lack of understanding when it comes to Heritage House imperatives to use old materials only, which are the most expensive (to the extent that some people cannot afford renovating their houses, see Figure 15.4) and seen as less solid. As one of my informants stated, ‘the problem with moladok is that they want us to preserve everything “old style”, whilst people here wants to make modern adaptations. Heritage House is too obsessed with the ancient’.

Figure 15.4 Some families cannot afford repairing their traditional houses with old materials

This kind of rhetoric is rooted in a shared political narrative about accessing modernity and, within the context of post-war Lao, this narrative is undoubtedly not nostalgic (Evans 1998). Whilst experts cling to nostalgia, many inhabitants are not lamenting the vanishing of an idealised epoch, like this interlocutor who told me that ‘things have changed a lot here since 1995, and that’s very good like that’. Locals are clearly not fully enamoured of the past saved by UNESCO and other heritage organisations and advocates. For many of these who, for instance, gain benefits from the UNESCO-isation, the past is the past and was not a better world than today: ‘We have no regrets, before was good, now it’s even better’, says another. Local discourses tend to emphasise an aspiration toward modernity, with a desire to see ‘even more tourists and planes flying to Luang Prabang’. In such a context, worldwide heritage recognition is associated with rapid changes rather than with continuity. Local attitudes toward preservation are seen as a step into, rather than a retreat from modernity, like the Luang Prabang imagined by experts or foreign travellers visiting the place. Preserving traditional houses, besides sustaining tourism, is seen by many as a way to conserve relics of the past for future generations, ‘to remember how we lived in the past’ and ‘to show to our children and grandchildren, but we don’t want to live in them anymore’.

Hopes and Fears

The discourse of Lao state officials toward Luang Prabang heritage functions similarly and it is evidently not nostalgic. As Long and Sweet have shown, the colonial past, traditional houses and rituals which UNESCO contributes to preserve, is intimately connected to royal history and heritage, a nowadays silenced period of the town’s history and a very sensitive topic for research. The museumification of Luang Prabang, which freezes the royal past and renders it harmless to the present, has also to be understood through the lens of Lao nationalism which ‘strategically uses the assistance of global organisations such as UNESCO to further its nationalist aims – that is, the development and maintenance of a distinctive version of Lao nationhood’ (Long and Sweet 2006: 449). As a reminder, Grant Evans (1998: 122) underlines that, in 1975, revolutionaries immediately transformed the king’s palace into a Royal Palace museum with the political intention to depoliticise it and to keep this past under control.

However, claiming absence of nostalgia for the past in Luang Prabang would only provide a partial picture of the current situation. Indeed, Lao elites feel sad about the rapid loss of culture, like this intellectual emphasising that ‘UNESCO is good. But since UNESCO is here, there are only Europeans in the streets. We are worried that we are going to lose our culture now’; whilst, as I’ve said earlier, exiles returning to Laos (after having lived for thirty years abroad) lament the disappearance of the Luang Prabang they have known before 1975. There are indeed many old people who secretly keep nostalgic memories of the Ancien Régime. Numerous elderly people in town lament cultural transformations, denouncing for example changes in female clothing or hairdressing and youth behaviours. Some residents feel sad about alterations of sociability (‘people have less time for family and friends because it’s all about business now’) and many do index dire practical consequences of tourism to their lives (with, for instance, the expansion of airport and drug smuggling for tourists). In addition, others criticise monks who spend their time running after tourists and in internet cafés.

Rapid changes do indeed produce certain anxieties about the future. Interestingly, these fears take for some the form of postcolonial imagination. In Luang Prabang, I have heard many people gossiping about the risk for the town to become a ‘meuang Falang’ (literally a ‘French town’ and by extension a town of ‘Westerners’), like one man suggesting that ‘within ten years, there will be only Falang in town. They buy everything here’. For some, Heritage House works hand-in-hand with foreigners ‘to transform Luang Prabang into a meuang for Falang only’ and moladok is seen as a ‘new form of colonisation by the French’ (whilst others emphasise that its role is precisely to control foreign investors in town). Practically, such ideas are reinforced by certain Heritage House officers, the Lao ones, when sanctioning locals about heritage regulations. As I have observed, some tend to always defer to the ‘Falang’ superior decision, which allows them to escape blame in the face of locals and to delegate responsibility to the former French colonisers (about similar bureaucratic deference, see Herzfeld 1991). All in all, these gossips and interactions are revealing of the feeling of dispossession especially in such post-colonial contexts and, also, of the uncertainty under which many residents live.

Contrary to UNESCO-related experts and a segment of the local elite, few locals say that they regret the demolition of old houses and that they fear the disappearance of traditional rituals. I found that the way most Laotians speak about permanence and loss does not correspond to the sense of loss expressed by UNESCO experts, Lao elites, Western expatriates or travellers. For instance, I have been struck by how little elderly people as well as most young generations do actually complain about the possible vanishing of the Tak Baad ritual. As stated earlier, for some in Luang Prabang, Tak Baad has become a metaphor of cultural loss, a concern also shared practically by some religious leaders, whose temples are located within the tourist area. Although these alarmist discourses are now circulated more and more through campaigns launched by expatriates and Lao elites, many of the inhabitants rather insist on cultural persistence, emphasising that they are ‘keeping on with tradition. Tradition is not changing’. For one woman, ‘custom is not disappearing, even with tourism. Lao people do conserve their traditions. Tak Baad won’t vanish. It’s a Lao tradition’, whilst for one elderly man, ‘even if people rent their houses and leave the town-centre, I am not worried. Even with Falang, Lao tradition will persist. Lao tradition is always the same. And now the Falang help the Lao to preserve Tak Baad’. In fact, interviews with locals revealed that they do not long for the return of what seems to some foreign experts and tourists lost for ever and that they do not share most traits of their cultural alarmism.

Discussion

In this discussion, I would like to focus on two reflections that emerge from the Luang Prabang example and make it such a case worth analysing for scholars studying contemporary heritage politics in Asia. First of all, Luang Prabang constitutes an arena where a diversity of perspectives around loss and heritage coexist, demonstrating without a doubt how ‘priorities, assumptions, and methodology of Western-Cultural “international” heritage charters are not always transposed easily to Asian countries’ (Howe and Logan 2002: 248). In fact, UNESCO experts, foreign tourists, expatriates and Lao elites share a sense of longing for the ancient and, in some case, do glorify the Indochina past, an image used by tourist companies and private investors. Such an image is beneficial for tourism development and seems to converge with Lao nationalist readings of history, freezing royal and Indochina pasts as ‘things from the past’, thus harmless to the present. Contrarily to the Danish nostalgiascape described by Gyimothy, in Luang Prabang, it is implemented through top-down strategies from which many urban residents were excluded and mostly external, i.e., rooted in Western notions of authenticity and heritage based on the conservation of old houses and intact temples and, above all, on the ‘spirit of the place’ which does not fit with most inhabitants’ conceptions, although it now seems right for economic reasons.

Denouncing Eurocentric politics of heritage, targeted from the outside, and the lack of integration of the local community within heritage projects, similar observations have been made for many World Heritage sites in Asia (Winter 2007, Shepherd 2006, Peters 2001) and around the world (Joy 2007, Scholze 2008). Inscribed as a WH Cultural Landscape in 1995, the Rice Terraces of the Philippine Cordilleras (Aplin 2007) are paradigmatic of the tensions existing between universalistic values of protection and local concerns, in particular when it comes to preserving lived heritage in changing worlds. Yet, such truism in heritage studies and anthropology begs another very important issue which remains to be explored. Although I have presented Luang Prabang as a field constituted of multiple perceptions about cultural transmission and loss, one should also wonder how it all holds together. How thus to explain the persistence of interconnections around heritage, when multiple parties (UNESCO planners, government officials, vendors, inhabitants, expatriates) seem not to understand each other, not to share a common sense of heritage, but still produce something together, complicit in rallying around an imagined symbol in order to advance their own disparate interests? A locus of conflicting values, Luang Prabang also represents an illustration of diverse people with various interests converging around heritage. In contemporary Asia, where colonial legacies, nationalistic projects, cultural globalisation and economic prosperity are inextricably interwoven within heritage-making politics, such convergence should definitely be explored further.

Acknowledgements

I have benefited tremendously from the generous comments of Chiara Bortolotto, Olivier Evrard, Pierre Petit, Nathalie Heinich, Catherine Choron-Baix, Anne Allison, Charles Piot, Ayse Caglar, Galina Oustinova and Jean-Louis Fabiani. The final shape of this text is due to the critical input and support of the editors, Patrick Daly and Tim Winter.

Notes

1 Scholars have started taking UNESCO bureaucratic discourses and practices as a field site where notions of culture, heritage, loss and authenticity are being produced and debated. See Bortolotto (2007), Ericksen (2001), Hafstein (2007).

2 In particular, as part of the convention France-UNESCO, a special cooperation has been established between the French town of Chinon and Luang Prabang, through the mediation of Deputy Yves Dauge who, after visiting the region, decided to help preserve it.

References

Aplin, G. (2007) ‘World heritage cultural landscapes’ International Journal of Heritage Studies, 13.6: 427–446.

Appadurai, A. (1996) Modernity at Large. Cultural Dimensions of Globalization, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Berliner, D. (2011) ‘Luang Prabang, sanctuaire Unesco et “paradis gay”’, Genre, Sexualité et Société 5.

Boccardi, G. and Logan, W. (2007) Reactive Monitoring Mission to the Town of Luang Prabang World Heritage Property. Lao People’s Democratic Republic. 22–28 November 2007, Mission Report.

Bortolotto, C. (2007) ‘From objects to processes: UNESCO’s intangible cultural heritage’, Journal of Museum Ethnography, 19: 21–33.

Boym, S. (2001) The Future of Nostalgia, New York: Basic Books.

Caton, K. and Santos, C.A. (2007) ‘Heritage tourism on route 66: deconstructing nostalgia’, Journal of Travel Research, 45.4: 371–386.

Cunningham Bissel, W. (2005) ‘Engaging colonial nostalgia’, Cultural Anthropology, 20.2: 215–248.

Dann, G. (1998) ‘“There’s no business like old business”: tourism, the nostalgia industry of the future’, in W. Theobald (ed.) Global Tourism, 2nd edn., Oxford: Butterworth Heinmann.

de Boeck, F. and Plissart, M.F. (eds) (2004) Kinshasa: Tales of the Invisible Town, Tervuren: Royal Museum for Central Africa, LUDION and the Flemish Architecture Institute.

Ericksen, T. (2001). ‘Between Universalism and Relativism: A Critique of UNESCO Concept of Culture’, in J.K. Cowan, M.-B. Dembour and R.A. Wilson, Culture and Rights: Anthropological Perspectives, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Evans, G. (1998) The Politics of Ritual and Remembrance. Laos since 1975, Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Foucault, M. (2009) Le corps utopique, suivi de Les Hétérotopies, Paris: Nouvelles Editions Lignes.

Gyimothy, S. (2005) ‘Nostalgiascapes: The renaissance of Danish countryside inns’, in T. O’Dell and P. Billing (eds) Experience-scapes: Tourism, Culture and Economy, Copenhagen: Copenhagen Business School Press.

Hafstein, V. (2007) ‘Claiming culture: intangible heritage inc., folklore©, traditional knowledge™’, in D. Hemme, M. Tauschek and R. Bendix Prädikat ‘Heritage’–Wertschöpfungen aus Kulturellen Ressourcen, Munster: Lit Verlag.

Herzfeld, M. (1991) A Place in History. Social and Monumental Time in a Cretan Town, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Howe, R. and Logan, W. (2002 ‘Protecting Asia’s urban heritage: the way forward’, in W. Logan (ed.) The Disappearing ‘Asian’ City: Protecting Asia’s Urban Heritage in a Globalizing World, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

ICOMOS (2008) Québec Declaration on the Preservation of the Spirit of the Place. Adopted at Québec, Canada, 4 October 2008. Online: www.international.icomos.org/quebec2008/quebec_declaration/pdf/GA16_Quebec_Declaration_Final_EN.pdf (accessed 28 December 2009).

IMPACT (2004) Tourism and Heritage Site Management in the World Heritage Town of Luang Prabang, Lao PDR, Office of the Regional Advisor for Culture in Asia and the Pacific, UNESCO Bangkok and School of Travel Industry Management, University of Hawai‘i.

Ivarsson, S. (2008) Creating Laos: The Making of a Lao Space between Indochina and Siam, 1860–1945, Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies.

Jankélévitch, V. (1983) L’irréversible et la nostalgie, Paris: Flammarion.

Joy, C. (2007) ‘“Enchanting town of mud”: Djenne, a world heritage site in Mali’, in F. De Jong and M. Rowlands (eds) Reclaiming Heritage: Alternative Imaginaries of Memory in West Africa, Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press.

Kennedy, L. and Williams, M.R. (2001), ‘The past without the pain: the manufacture of nostalgia in Vietnam’s tourism industry’, in Hue-Tam Ho Tai (ed.) The Country of Memory. Remaking the Past in Late Socialist Vietnam, Berkeley/London: University of California Press.

Long, C. and Sweet, J. (2006), ‘Globalisation, nationalism and world heritage: interpreting Luang Prabang’, South-East Asia Research, 14.3: 445–469.

Norindr, P. (1997) Phantasmatic Indochina: French Colonial Ideology in Architecture, Film, and Literature, Duke: Duke University Press.

Pan, T. (2007), Neighborhood Shangai, Shangai: Fudan Press.

Peleggi, M. (2002) The Politics of Ruins and the Business of Nostalgia, Bangkok: White Lotus Press.

Peleggi, M. (2005) ‘Consuming colonial nostalgia: The monumentalisation of historic hotels in urban South-East Asia’, Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 46.3: 255–265.

Peters, H. (2001) ‘Making tourism work for heritage preservation: Lijang–a case study’, in T. Chee-Beng, S. Cheung and Y. Hui Tourism, Anthropology and China, Bangkok: White Lotus Press.

Pickering, M. and Keightley, E. 2006, ‘The modalities of nostalgia’, Current Sociology, 54.6: 919–941.

Rosaldo, R. (1989) ‘Imperialist nostalgia’, Representations, 26: 107–122.

Shepherd, R. (2006) ‘UNESCO and the politics of heritage in Tibet’, Journal of Contemporary Asia, 36.2: 243–257.

Scholze, M. (2008) ‘Arrested heritage: the politics of inscription into the UNESCO World Heritage List: the case of Agadez in Niger’, Journal of Material Culture, 13.2: 215–232.

Stuart-Fox, M. (1997) A History of Laos, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Winter, T. (2007) Post-Conflict Heritage, Postcolonial Tourism: Culture, Politics and Development at Angkor, London: Routledge.