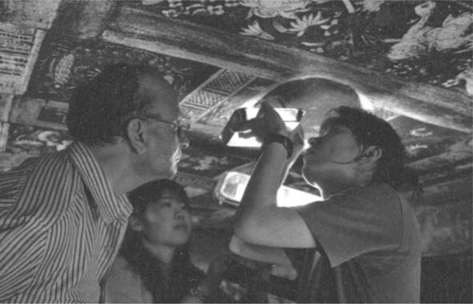

Figure 22.1 Overview, Ajanta Caves (Photo A. Toyoyama)

22

Perceptions of Buddhist Heritage in Japan

Introduction: Modernity and Heritage in Asia

Since 1992, the Japanese government has provided an Official Development Assistance (ODA) loan for the ‘Ajanta-Ellora Conservation and Tourism Development Project’. According to the official website of the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the project is explained as follows:

The (Second Phase) Ajanta-Ellora Conservation and Tourism Development Project will receive loan assistance of 7,331 million yen. This comprehensive project, besides involving conservation and protection of the world famous rock-cut shrines of Ajanta and Ellora, also includes improvement of airport facilities, and establishment and improvement of tourism-related infrastructure facilities. Through exploiting the potentials of these World Heritage monuments, the project aims not only to achieve greatly enhanced tourism in the region and also thereby to help promote regional development. The project will be implemented by the Ministry of Tourism, Government of India.

(Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 2003)

This is one of a number of major conservation and development projects that Japan supports across Asia. The first phase of the project was recently evaluated. According to the evaluation report, more intensive efforts to maintain the authenticity of the overall site and to include more active participation of local communities within the restoration and management has been left for the second phase of the project. Initial efforts have focused upon restoring the famous murals in the caves, and the exhibition and presentation of the murals have received high marks in the evaluation (Hidaka et al. 2007). The cave sites at Ajanta are world famous for being among the greatest and earliest examples of Buddhist art and are popularly visited by tourists from all over the world.

In this chapter I argue that there are, however, more particular reasons why Japan has invested resources into restoration projects at Ajanta. I build a case that this is related with more than a century of Japanese interest in a pan-Asia common Buddhist heritage. As I will show, this is deeply connected with the rise of modernity in Japan and reflects a form of Japanese Orientalism inspired by late nineteenth century relationships between Japan and the West. I use the example of Ajanta to show that in some Asian contexts, notions of modernity, heritage and identity are closely tied with Euro-centrism and colonial ideals (Lopez 1995).

Figure 22.1 Overview, Ajanta Caves (Photo A. Toyoyama)

Figure 22.2 Sampling pigments of murals at Ajanta cave 2 under the Indo-Japanese Project for Conservation of the Mural Paintings at Ajanta Caves (Photo A. Toyoyama)

Colonial perspectives promote the universality of Asiatic cultural modes, which present a usefully simplified and homogenised Asia, especially regarding religion and particularly Buddhism. European interests in Buddhism developed rather late in the Oriental Renaissance after the arrival of Sanskrit manuscripts in Europe in 1837 (Lopez 1995). Beforehand, interest in India as the birthplace of Buddhism was a subset of the broader study of Brahmanical culture. Buddhism as an object of Western knowledge began to be researched more intensely in the period when European colonial powers intensified their domination over much of Asia. This lead to a homogenisation of ‘things Asian’, as complex historical and cultural relationships were simplified to craft neat, linear narratives (this is also discussed in Ray, Chapter 4 of this volume). This line of thinking influenced local elites within Asia who were educated in Westernised systems. The European perception of a Buddhist Asia framed how many Western educated Japanese viewed the connections between Japan and much of Asia. By the end of the nineteenth century, this began to foster the exertion of Japanese colonialism throughout Asia. The idea of a broadly common cultural and religious heritage provided useful rhetoric for the expansion of Japanese culture in Asia and still is widely felt within Japan today.

Japan’s ODA loan provided for the famous Indian Buddhist sites Ajanta and Ellora, both of which are World Heritage sites situated in the Indian state of Maharashtra. This is an important representation of Japanese cultural identity and its constructed relationship with heritage in Asia. The significance of the sites primarily pertains to their rock-cut caves, with around thirty caves found at each location. The Ajanta caves date back as far as the second century BCE and include paintings and sculptures considered to be masterpieces of both Buddhist religious art, as well as frescos similar to those found at Sigiriya in Sri Lanka (see Figure 22.3). At Ellora, the hillside structures and excavated openings are more recent, built between the fifth and tenth centuries. As such, they are associated with the Buddhist, Hindu and Jain faiths. The ODA project for Ajanta-Ellora conservation is an indication of the importance that such early Buddhist sites play in Japanese cultural identity. Japan’s commitment to conserve this heritage derives in part from its imagining of India as the source of Japanese Buddhist culture and from a desire to reposition the country’s relationship with Buddhism more generally. However, as this chapter demonstrates, this perspective did not emerge until the late nineteenth century when Japan underwent transformations during which it modernised and Westernised its administrative and economic systems and began adopting European perspectives regarding what constitutes ‘Asia’. Indeed, the Japanese connection with India is part of a history of a Japanese expression of Orientalism, crafted through both engagement with Western forms of knowledge production and Japanese political ambitions. It is thus necessary to analyse Japan’s Oriental perspective carefully and critically to understand Japanese modernity and its impact on heritage in Asia.

Figure 22.3 Mural depicting place scenes from the Visvantara Jataka, Ajanta cave 17 (Photo A. Toyoyama)

This chapter thus reconsiders the emergence of Asian Orientalist ideas, aesthetics, art history and heritage in the context of socio-political and religious changes in Japan, focusing on the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It starts by outlining European perceptions of Indian antiquity through its cave temples, particularly the changing production of colonial knowledge after the discovery of elements of fine art in these ruins. Secondly, it discusses the context in which Buddhist religiosity became widely seen as a pan-Asian phenomenon and demonstrates Japan’s engagement with this concept. Finally, it discusses the role of art history in constructing the idea of a ‘Buddhist Asia’.

The Western Perception of Indian Cave Temples and Japan’s Commitment to Ajanta-Ellora Conservation

The earliest attention paid to Indian rock-cut caves as sites of heritage in the modern context can be traced to the early sixteenth century. John Huyghen van Linschoten (1885), a Dutch traveller, noted the caves at Kanheri and Elephanta Island. Sixteenth century Portuguese historian Diego do Couto (Fletcher 1841a, 1841b) and seventeenth century British traveller John Fryer also mentioned the caves in their writings (Fryer 1909). These documents were focused on sites located around the Bombay harbour, given its importance as a major trading centre for European merchants. Interestingly, some of these initial accounts of the caves were negative, emphasising their ‘fearful’, ‘horrible’ and ‘devilish’ nature. Here, these ‘abandoned’ cave sites played into stereotypes of a primitive India.

In the eighteenth century, Britain expanded its sovereignty in India. Its extension further into the subcontinent increased the opportunity for British officials to encounter its rich cultural heritage. Initially, there was significant British attraction to the many ruined temples and monuments scattered throughout India. During this period, it was typical for landscape paintings in England to be dominated by natural settings, dotted with ruined structures. The few human figures and animals depicted were mostly very small in scale and clearly of secondary importance to the portrayal of the landscape and the decaying remains of human construction, which were connected with rapid industrialisation in England. British officials and their draftsmen in India were aware of well known cave temples of Kanheri, Elephanta and the others in the vicinity (such as Ellora), as those sites had been well represented in picturesque drawings by Europeans (Mitter 1977). Such sites fit neatly with the prevalent European landscape aesthetic at the time and resonated with colonial ideals of discovering the remains of ‘lost’ civilisations.

The perception of Indian caves and archaeology was changed dramatically in the early nineteenth century by the discovery of the Ajanta caves by officers of Madras army of the British Raj. Although Indian ruins have been admired as picturesque during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, this appreciation was grounded in their cultural and temporal ‘otherness’ and disconnected from European ideas of art. The ‘discovery’ of the elaborate murals inside the caves at Ajanta shifted prevailing European notions of Indian archaeology and some Indian ruins began to be appreciated as ‘fine art’.

This perceptive shift is also part of a broader reconsideration of antiquities collected from other colonies, including Egypt (Whitehead 2009). In England there were debates about the nature of fine art, which was considered to include painting, sculpture and architecture. The discovery of Ajanta caves had a great impact on Europeans, as it showed the existence of a long history of (what Europeans considered to be) ‘fine art’ in India. The consequent approach in antiquarian scholarship was totally different from other remains. The murals were appreciated as examples of fine art, which can be seen in their reproduction by numerous European artists, among them John Griffiths, the director of the Bombay School of Art, who commented: ‘There are no other ancient remains in India where we find the three sisters arts – Architecture, Sculpture and Painting – so admirably combined as we do at Ajunta’ (Griffiths 1896-97). From the perspective of patrons of European ‘high culture’, India had presented a form of cultural achievement that fit well within paradigms of art history in Europe.

In the nineteenth century, increasing efforts were made to survey the Indian subcontinent by the British colonial government. This focused upon better understanding both the physical environment and the cultural and social makeup of India. During this period, a compilation of voluminous and informative gazetteers covered all aspects of India (see Campbell 1877–1904). As part of the process of mapping the Indian subcontinent, people and cultural practices were recontextualised to fit within the categories and frameworks of the colonial authorities. The establishment of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) also accelerated the investigation of heritage in India and introduced material as a valid way to explore Indian history. Initially the ASI focused almost exclusively upon architecture and above-ground sites of historic interest. This was especially the case in the Western Indian branch, where the ASI surveys of the rock-cut caves drew considerable interest (Singh 2004). In addition to the Archaeological Survey of Western India, the internal committee of the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society (RAS) investigated cave temples and made extensive surveys of their distribution. Additionally, the RAS contributed to deciphering inscriptions on the cave wall.

The accumulation of information on the western Deccan caves and other Indian monuments gradually enhanced their position as important heritage sites as detailed information on the cave structures and interior decorations resonated with common European aesthetic sensibilities. It is not surprising that this led to frequent misconceptions in the analysis and interpretation of Indian artistic accomplishments, as carvings, structures and paintings were slotted within European artistic standards. As part of this research, Europeans were concerned with connecting the cave complexes within a religious context. This period represents a significant shift in the European conceptualisation of both Indian religion and history as haphazard encounters by individuals were replaced by the more systemic recording and interpretation of sites, as well as an increasing reliance upon texts.

A number of factors contributed to an increasing European interest in and admiration for Buddhism. This is partly because the philological commonality of Sanskrit and European languages allowed Europeans to imagine ancestral connections, as well as some shared cultural traits. Additionally, to many Europeans, Buddhism provided a broad form of ‘Oriental’ philosophy, of sufficient intellectual depth and sophistication to be considered alongside Greek, Roman and Egyptian classical thought. Finally, this romanticised view of Buddhism as an intellectual counterpart to classical European thought contrasted neatly and conveniently with European opposition to and distaste for Brahmanism, which was widely seen as a backward superstition responsible for the decay of Indian civilisation.

This perspective influenced antiquarian thought, which sought evidence for India’s glorious Aryan past and led to the emergence of new approaches to the archaeology, art and heritage of Buddhism. It is within this intellectual milieu that the concept of ‘Buddhist Asia’ as a homogenous cultural framework was created. This fed into a flurry of activity by British officials, missionaries and merchants to accumulate information on Buddhist heritage, some of which was compiled and published. The wide distribution of these publications around the world both propagated the pan-Asian narrative throughout Europe and introduced to Asians these European perceptions of Asia as a region. This interesting twist led to a self-processing of Asian cultural identity, framed by colonial perspectives of Asia, which was integrated into the socio-political ideology of Asian countries.

Such publications and articles became accessible in Japan in the second half of the nineteenth century. This was a time of dramatic socio-political modernisation and coincided with the construction of a new identity for Japan as a nation-state. In the next section, I focus upon Japan’s development as a ‘modern’ nation state. This process was characterised by changing perceptions on religion and influenced by European perceptions of Asia, which led to the adoption of aspects of European political and economic systems.

The Beginning of Japanese Modernity: Socio-Political and Religious Changes in the Late-Nineteenth Century

The modernisation of Japanese politics began in the 1860s when the Tokugawa Shogunate was defeated by an alliance of loyalists. This political transformation is called the Meiji Restoration after the Emperor Meiji (1852–1912) who ascended the throne in 1867 at the age of fifteen (Varley 2000). A major element in the restoration was that of reconfiguring the basic sociopolitical role in modern Japan. By establishing the Emperor as a symbol of the state, the Meiji leaders put Shinto forward as a national religion. Until the end of Shogunate sovereignty, the Japanese belief system had been based on Shinto-Buddhist syncretism, which had developed over centuries (Murakami 1986). When a Shinto shrine and Buddhist temple existed in a single regional community, the Buddhist temple was the authority for local social administration and governance. The Shinto centralisation of the state emerged from anti-Shogunate and anti-feudal sentiments. Shifting the emphasis to Shinto was part of the Meiji administration efforts to craft a single cultural Japanese identity (Murakami 1986). To consolidate and establish Shinto into a national religion, it was essential to separate Shinto and Buddhism.

The overthrow of the Tokugawa Shogunate was philosophically led by intellectuals opposed to Buddhism, Confucianism and syncretistic Shinto, all of which contributed to the Shogunate administration. On 28 March 1868, the Meiji government proclaimed the Shinto-Buddhism Separation Edict. It replaced the Edo-era requirement that every person register at a local Buddhist temple with a system of compulsory registration at local Shinto shrines. This transformation of social identity emphasised that Shinto and Buddhism were different belief systems and resonated with people who were discontented with the oppression of the Shogunate rule and especially those who saw Buddhist organisations as complicit. The social instability associated with the Meiji Restoration encouraged the attacks on Buddhist temples (Gordon 2003). As anti-Buddhist movements gained traction in different regions and were initiated as part of the restoration, a number of unforeseen factors drew Buddhism back into the mix.

The Meiji government found that the wide scale adoption of Shinto was not conducive for the establishment of a modern nation-state in Japan (Arai 2008), much of which had to do with interactions with the West. Firstly, the swelling ranks of foreigners in Japan, including many Europeans and Americans, brought a significant Christian presence. In order to accommodate these expatriates seen as critical to the development of Japan, it was necessary for the Meiji government to end the ban on other religions, including Buddhism. However, the question still remains as to why Buddhism rebounded so quickly, given the earlier official suppression of it. One factor seems to be related to the increasing relations with the West, in that Buddhism and its philosophical universality was more understandable to Westerners than the countless variations of Shinto (which were local and diverse).

Just as the British were suspect of Bramanism in India and gravitated towards the universal allure of Buddhism, the Westerners in Japan did the same. It was easier for the West to understand Japan through such a universal perspective rather than a heterogeneous indigenous culture. Or at least Japanese elites anticipated this to be the case and played up this angle. Recognising the West’s attraction to Buddhism, local elites in Japan who were educated in Western systems represented Buddhism as a counterpart to Christianity to improve the status of Japan within international circles. This recognition forced Meiji leaders to become tolerant of Buddhism (as well as Christianity) due to diplomatic and commercial benefits.

Ironically, another contributing factor to Buddhism’s traction in Meiji Japan was that of early Meiji Japan anti-Buddhist movements, which heavily demolished Buddhist cultural properties. The remnants of these political demolitions – statues, objects and other antiquities from destroyed Buddhist temples – flowed out of Japan into international art markets. This raised the profile of Japanese Buddhist artistry and increased awareness of the value and interest in Buddhist cultural heritage both locally and internationally. Seizing advantage of this interest, the Meiji government began to emphasise Japan’s Buddhist identity to capitalise upon the currency of Buddhist culture internationally. As Tanaka (1994) has pointed out, this new identity defined Japan’s historical relation to Asia and created a new geo-cultural entity, tōyō (Orient), to share the identity of Buddhist Asia. This began the process of increasingly defining Japan by pan-Asian connections, through which Japan abandoned its long-standing isolationism. This was part of a set of complex processes that gave rise to policies of intra-Asian colonialism by the Japanese government.

The Making of Cultural Identity in Modern Japan: the Development of Japanese Art History

In the political restoration of Meiji Japan, which merged philosophical classicism and utilitarian Westernisation, reconnecting with a glorious past was a useful way to crystallise national identity among the Japanese people. Indeed, the making of Japanese art history as a discipline was a part of the strategic historiography of the Meiji administration in the modernising process of the state formation. Developing a self-consciousness of one’s culture and tradition benefits from perceptions of ‘the other’. In the context of Japanese art history, this ‘other’ was Western fine arts, which were introduced with the opening of the country in the late Tokugawa Shogunate era. This was furthered by the establishment of a governmental arts school by the Meiji administration where students were taught Realist perception and techniques that dominated the contemporary European art world (Varley 2000). In addition to diplomats, many Westerners were invited as oyatoigaikokujin or hired foreigners as teachers and engineering instructors and this included an increasing numbers of artists.

Ernest F. Fenollosa (1853–1908), an American lecturer in philosophy at the Imperial University of Tokyo, came to Japan as oyatoigaikokujin. He was instrumental in the development of a formal approach to Japanese Art History and its aesthetic values. Attracted by a Hegelian view of the world, he had been highly interested in aesthetics since his studies at Harvard. Upon his arrival in Tokyo in 1878, Fenollosa frequently travelled to Kyoto and Nara with his pupil Okakura Tenshin (1862–1913) to investigate antiquities in Buddhist temples, many of which had been disturbed by anti-Buddhist movements. Inspired by what he saw on his travels, Fenollosa developed the impression that Japanese Buddhist art was much influenced by classical or Greek art, most notably in its possession of ‘feeling’, which he held as the essential element of fine art. In his Epochs of Chinese and Japanese Art, he wrote:

It is likely that a great experiment on classical Buddhist art was firstly attempted to the west of the Nara plain … Here, in 1880, among a number of fragments of the Buddha images, I found a life-size statue that shows originality of classical Buddhism.

(Kurihara 1970)

Fenollosa’s interpretation of classical Buddhist art is closely related to the history of Buddhist art, which was developing throughout colonial Asia. This theory held that the emergence of the image of the Buddha in the Gandharan region of India was influenced by Greco-Roman art. Fenollosa stated that this genealogy of classical Buddhism, influenced by European classical art, eventually reached Japan. Fenollosa’s announcement of classicism in Japanese Buddhist art indicated a profound change from the prevailing Western views on Japanese art, which were strongly infused with exoticism and Orientalism. Within Japan his view was well received and he became respected as a preserver and advocate of Japanese art. But Fenollosa was not a lone exception, as there were other foreigners enthusiastic about collecting Oriental antiquities. In fact, Fenollosa’s life in Japan was supported by William S. Bigelow (1850–1926), an American doctor and great collector of Japanese art. Succeeding his father, Bigelow amassed a large and diverse collection of Japanese art which he bequeathed to the Museum of Fine Arts of Boston. Fenollosa added to the collection in Boston by selling the Museum his Japanese art collection which consisted of more than a thousand paintings and art objects (Conant 1995).

While Fenollosa is distinguished by his efforts that resulted in an outward flow of Japanese art to Europe and America, his pupil Okakura Tenshin seems to have been the real engineer of the development of Japanese art history. His Japanese Art History was plotted as a history of the selfconsciousness of artistic spirit, highly influenced by Hegelian views that he learned from Fenollosa in his youth (Kanbayashi 2002). Okakura (1976) classified the chronology of Japanese art into three periods and explained their characteristics as follows:

The history of Japanese art is classified into the Classical Age, Middle Age and Early Modern Age. The Classical Age coincides with the Nara dynastic period, the Middle Age with the Fujiwara dynastic period, and the Early Modern Age with the Ashikaga dynastic period. The art of the Nara period is idealistic. The Hinayanistic character of Buddhism considers that the sacred and earthy worlds are distanced so that the Buddha images show supremacy. The art of the Middle Age is emotional. The Tantric character of Buddhism considers that the Buddha has emotion, and that the sacred and earthly worlds are close. The Ashikaga period became self-conscious of emotion. Therefore, the characteristics of Japanese art are divided into idealistic, emotional, and self-conscious.

As Kanbayashi (2002) pointed out, the introduction of Japanese art, influenced by Hinayanistic ideals in the Nara period, laid down the foundation for an emotional art based on Mahayanistic and Tantric ideals of Buddhism. In the final stage, the self-consciousness of art was connected with the spirit of Zen Buddhism. It seems that Hegelian understandings of self-consciousness resonated within the philosophical development of Buddhism in Japan.

Furthermore, an idea of the universality of Japanese culture was strengthened by Okakura during his experience in India between 1901 and 1902, with the Ministry of Home Affairs. Although Okakura did not keep a detailed itinerary or diary of his own, his schedule can be partially traced through documents kept by people whom Okakura met in India, including a Hindu philosopher Vivekananda (1863–1902) and Asia’s first Nobel laureate, Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941). It seems that Okakura’s passage to India was a turning point in his perspective on the position of Japan on the international stage. During his stay, he wrote The Ideals of the East (1976) and The Awakening of the East (1976), both of which show the emergence of pan-Asianism in his mind.

After his return to Japan, Okakura wrote at least three articles on his Indian experience, focusing upon his impressions of Indian art. He repeatedly mentioned the similarity between Indian and Japanese art:

In the second phase of Indian Buddhism during the fourth and eighth centuries, the influence of Indian art reached Japan through China. The techniques of the Ajanta murals are closely similar to those of the Golden Hall in our Hōryū-ji Temple.

(Okakura 1976)

He also emphasised the differences of Eastern and Western perspectives as follows:

There must be the close relationship among Indian, Chinese and Japanese art. Traditionally, we have studied Indian art through foreign scholarship, particularly British scholarship. However, their perspective and our perspective are different.

(ibid.)

Okakura’s contextualisation of Japanese culture in an Asian framework was part of a broader effort to establish a distinct Asian perspective on culture and tradition and seems to have been part of his deliberate strategy to emphasise Japan’s Asian cultural identity. Although Okakura was highly absorbed into a Western-filtered perspective because of his English-based education, he attempted to adapt Western perspectives on Japanese culture through embracing the ideal of Buddhist universality and by positioning Japan within it. In other words, he utilised the colonisers’ logic to demonstrate the global modernity and cultural maturity of Japan as a nation-state. The emblematic notion of his cultural policy was manifested in the ‘Ajanta and Hōryū-ji Temple link’ theory.

The pan-Asiatic cultural framework demonstrated by Okakura fed into the development of Japan’s colonial ideology which increasingly came to define its intra-Asian relations. For example, he promoted Japan as a terminal of cultural transmission where foreign and indigenous cultural elements integrated into the most matured forms (Okakura 1979), creating higher levels of thought and culture. The Shinto imperialism of Japan was ironically corroborated by the universality of Buddhism and consequent pan-Asianism, despite the fact that the initial modernisation had attempted to exclude Buddhism. The awareness and utilisation of Buddhism, framed by European colonial perspectives, became a force for Japanese national identity and served in part to legitimate the intra-Asian colonial power of the Shinto imperialism.

The motivation of the present assistance to Ajanta and Ellora by the Japanese government has its fundamental roots in the colonial framework of Asian culture which developed through the substantial notional construction of modernity in the late nineteenth century. The World Heritage sites of Ajanta and Ellora in India and the Hōryū-ji Temple in Japan seem to symbolise a shared modernity and interrelations in Asia. The making of Japanese art history in the process of modernisation thus contributed to establish Japan’s Orientalism, or pan-Asianism, through a Buddhist universality which continues to influence Japan’s engagement with heritage.

Conclusion: The Modernity of Heritage in Asia

Ongoing heritage conservation in Asia, including Japan’s ODA, has its ideological basis in European colonial perceptions of heritage and its regional/intra-regional embodiment or reproduction of culture and tradition. In the context of modernisation, the construction of a unified cultural identity is crucial to the crystallisation of a nation-state and, for Japan, Buddhism has been operationalised to this effect. In the face of Shinto-Buddhism Separation policy and the subsequent anti-Buddhist movement, the recovery of Buddhism’s status in Japan was highly influenced by Western perspectives. The increase of Western residents in Japan required freedom of religion and belief, including Christianity and Buddhism. Further, the displacement and dispersion of Buddhist antiquities (due to anti-Buddhist movements) and coincident treasure hunting by Westerners opened Japan’s eyes to their aesthetic value, a perspective first advanced by Fenollosa and later by Okakura. This evaluation was influenced by the understanding of Buddhism as India’s Aryan past and its connection to Greco-Roman classicism in art. Moreover, the Western perception of the Orient through Buddhist universality gave Japan a new geo-cultural entity through which to contextualise their modern identity in a global context. As a result, the historiography of Japanese art contributed to legitimating the process of universal cultural value linked to the notion of heritage in Buddhist Asia today.

This chapter contends that Japan’s ODA is penetrated by a colonial and Orientalist Euro-centric perception of culture and tradition. Therefore, its conservation and tourism development is scientifically highly qualified, but the concept and policy of heritage seems not to coincide with the development of postcolonial perception. This is because since the nineteenth century, when Japanese society shifted drastically into modernisation, Japan has taken its ideological Oriental identity from outside of the Orient. A once hybrid and syncretistic belief system split into Shinto and Buddhism enabled the utilisation of the latter for framing a single universality of Asia. This was a political contextualisation and a statement that stood until the end of the Pacific War. The continuation of such paradoxical Orientalism in post-war Japan may be caused by an ambivalent ideology – that between a longing for the pure Orient of their cultural origins and the socio-economical imperialism in Asia. Japan’s ODA loan seems to be an emblematic representation of this notion; the project implies close ties of modernity with Westernisation for the making of a nation-state in an Asian context through the emergence of an Oriental identity more or less influenced by colonial perceptions of Asia and through the geo-cultural entity substantiated by Buddhist heritage.

In relation to the discovery of universal cultural value through heritage, the science of cartography that was introduced by Europeans or colonisers and regionally adopted by colonies obviously requires the reconceptualisation of indigenous culturality through a postcolonial perspective. That is to say, the imaginings and perceptions of previously unknown, newly discovered land by physical and ideological mapping processes seems unfit for the current task of widening the notion of heritage. In the case of India, the map marking the sites visited by colonisers and the map of currently registered monuments (including the World Heritage sites) are greatly overlapping and similar phenomena may occur in other former colonies. The mapping, patterning and moulding of an Indian past through the perception of heritage has contributed to establishing cultural identity in inter-/intra-regional contexts. Furthermore, colonial translations of indigenous landscapes in Asia have developed a particularly Westernised or modernised identity for Asia and encouraged the reproduction of tradition. The historical insights introduced by this chapter, as they pertain to heritage in Asia (and its related discourse), may encourage further understanding of the nature of modernity in colonial and postcolonial Asia. Certainly, it leads to the deconstruction of a cultural identity of Asia, here seen to be underwritten by some form of Asian Orientalism. From here it may be possible to formulate new ideas on Asian heritage as it exists, as it is conceived and as it is managed in the future.

References

Arai, K. (ed.) (2008) Kokka to Shūkyō (Nation-State and Religion), Kyoto: Kyoto Bukkyō Kai.

Campbell, J. M. (ed.) (1877–1904) Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency, 27 Vols, Bombay: Government of India Central Press.

Conant, E. P. (1995) Nihonga: Transcending the Past, New York and Tokyo: Weatherhill.

Fletcher, W. K. (1841a) ‘Coutto’s Decade VII, Book III, Chapter X: of the famous island of Salsette at Bassein, and of its wonderful pagoda called Canari, and of the great labyrinth which this island contains’, Journal of the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1.1: 34–40.

Fletcher, W. K. (1841b) ‘Coutto’s Decade VII, Book III, Chapter XI: of the very remarkable and stupendous pagoda of Elephanta’, Journal of the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1.1: 40–45.

Fryer, J. (1909) A New Account on East India and Persia Being Nine Years’ Travels, 1672–1681, London: Hakluyt Society.

Gordon, A. (2003) A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present, New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Griffiths, J. (1896-97) The Paintings in the Buddhist Cave-Temples of Ajanta, Khandesh, India. 2 vols. London: Secretary of State for India in Council.

Hidaka, K., Saito, H., Yamato, S., Morgos, A., Yagi, H., Kuroda, N., Hanyu, F., Uekita, Y. and Matsui, T. (2007) Ajanta-Ellora Conservation and Tourism Development: Project 1: Special Evaluation from the View- point of the Preservation and Use as a World Cultural Heritage Asset. Online: www.jica.go.jp/english/operations/evaluation/jbic_archive/post/2007/pdf/te03.pdf (accessed 1 December 2008).

Kanbayashi, T. (2002) Bigaku Kotohajime [The Beginning of Aesthetics], Tokyo: Keisō.

Kurihara, S. (1970) Fenollosa to Meiji Bunka [Fenollosa and Meiji Culture], Tokyo: Rokugei.

van Linschoten, J. H. (1885) The Voyage of John Huyghen van Linschoten to the West Indies, London: Hakluyt Society.

Lopez, Jr., D. S. (ed.) (1995) Curators of the Buddha: The Study of Buddhism under Colonialism, Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan (2003) ODA by Region (South West Asia). Online: www.mofa.go.jp/policy.oda/region/sw_asia/loan0301.html (accessed 1 December 2008).

Mitter, P. (1977) Much Maligned Monsters: History of European Reactions to Indian Art, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Murakami, S. (1986) Ten’nō SeiKokka to Shūkyō [The Imperial State and Religion], Tokyo: Nihon Hyōron.

Okakura, T. (1976) OkakuraTenshin Shū [Selected Works of OkakuraTenshin], Tokyo: Chikuma.

Okakura, T. (1979) OkakuraTenshin Zenshū [The Complete Works of OkakuraTenshin], vol. 3, Tokyo: Heibonsha.

Singh, U. (2004) The Discovery of Ancient India: Early Archaeologists and the Beginnings of Archaeology, Delhi: Permanent Black.

Tanaka, S. (1994) ‘Imaging history: inscribing belief in the nation’, Journal of Asian Studies, 53.1: 24–44.

Varley, P. (2000) Japanese Culture, 4th edn, Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Whitehead, C. (2009) Museums and the Construction of Disciplines: Art and Archaeology in Nineteenth-Century Britain, London: Duckworth.