Figure 2.1

Abbey of Nonantola: tympanum (redeployed from a pulpit) (A.C. Quintavalle)

The image of the rule of Matilda of Canossa (1046–1115) that predominated in the historical studies of the first part of the last century, and indeed still does to some extent, is one of power over territories stretching from the river Po to the Apennines and into at least part of Tuscany, but not over the cities. In short, feudal lordship on the one hand and urban power with the growth of free communes on the other. I believe that this view, which is also often adopted by art historians, is in need of partial revision. It is true that we have many documents, particularly numerous in the case of San Benedetto Po (Polirone), attesting to Matilda’s constant interest in that monument, not to mention the traditional attention to Frassinoro and the importance ascribed by Donizo in the Vita Mathildis to the monastery of Sant’Apollonio at Canossa.1 Significance also attaches to the interest in Nonantola, where Matilda made major donations from 1091, having requisitioned and melted down the abbey’s treasure in 1084 to pay her troops in the fighting against the Empire.

The most recent studies suggest that Matilda’s policy was far more complex and should be interpreted at various levels.2 First of all, she may have wished to continue with the plans of her father Boniface and to make Mantua the capital of a realm possibly encompassing the whole of northern Italy. It was indeed precisely in Mantua that Boniface had his palatium built. While the project fell through in 1091, when the city fell to the emperor, this happened after a long siege. A significant number of citizens supported Matilda and were finally to abandon the city. Secondly the Great Countess was unquestionably interested in the abbeys, but these remained for her strategic places in a precise geographical vision designed to counter any possible invasion. Thus Frassinoro defended the road of the Apennine passes, as did the system of fortified castles that Matilda maintained in the area between Modena and Reggio Emilia. The abbey of San Benedetto Po occupied a key location with respect to the old and new courses of the river Po and its tributary, the Lirone. The rich abbey of Nonantola was the focal point of the confrontation between the bishops of Modena and Bologna, and finally Canossa was only one of the many castles of Matilda’s defence system on the Apennines, made famous by the clash between the pope and the emperor in 1077. It should not be forgotten that the abbeys were themselves places surrounded by walls, as in the case of Nonantola, and protecting an abbey therefore also meant maintaining a system of tutelage. The case of San Benedetto Po is different again, as it was affiliated to Cluny, a form of insurance, according to historians, with respect to the imperial authorities. Polirone was also important for the training of monks who were to fight, on being introduced into the secular clergy, on the side of the papacy for orthodoxy and against the empire.

The third point of Matilda’s policy, as indicated – I repeat – by the most recent studies, was a vast plan of penetration into cities strongly marked by the presence of allied vassals, capitanei, nobles and feudatories. I shall give just a few examples. In Modena it was precisely these figures, in addition to the cives representing the mercantile and manufacturing middle class, that undertook the construction of the cathedral as from 1099 in Matilda’s presence. In Parma she attempted to impose the bishop and papal legate Bernardo degli Uberti in 1101 and was forced to intervene in 1104 in order to free the prelate from imprisonment by supporters of the imperial party. It was not until 1106 that the bishop was finally able to establish himself in the city, and the resumption of building probably dates from then. In Cremona the existence of a power vacuum – like the absence of an orthodox bishop in Modena – enabled Matilda to intervene in connection with the rebuilding of the cathedral. These three examples are given in order to show how historians today also focus on the urban dimension of Matilda’s policy. I shall now seek, albeit perhaps in overly schematic terms, to highlight the close connection between the Gregorian Reform, the introduction of new, orthodox, abbots and bishops, and the rebuilding of monasteries and cathedrals at the very moment when they transferred their allegiance from the emperor to the pope.

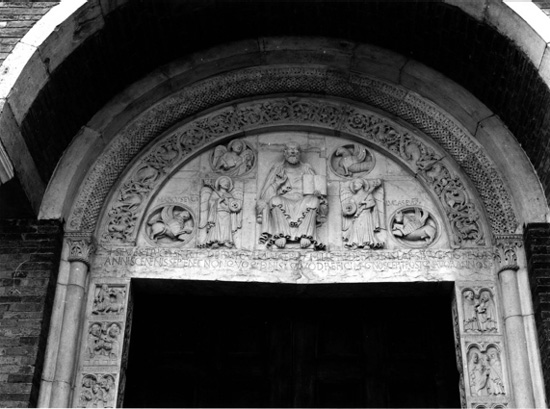

The abbey of Nonantola had pro-imperial abbots until 1073 and probably no abbot at all in the period 1074–75. As from 1086 the abbot was Damianus, a religious reformer and nephew of St Peter Damian. His period of office saw the rebuilding of the church, which probably began early in the next decade, as shown by the the most recent studies and the discovery of late-11th-century frescoes in the abbey’s chapter house.3 The Abbey church was severely altered as early as the end of the 12th century, and subsequently until the 18th, not to mention the wholesale restoration of the 19th and early 20th.4 It still retains a sculpted portal of great interest, where the inscription on the architrave attests to the collapse of the upper sections of the building in 1117 and its rebuilding ‘after four long years’, therefore beginning in 1121.5 The tympanum (Figure 2.1) was originally left open, the evangelist symbols were part of a pulpit and the Christ Pantocrator is from a screen, as the rear, which is part of a Roman frieze, must have been visible (Figure 2.2).6 The monastery of Frassinoro was founded by Matildaʼs mother Beatrice in 1071 and its markedly ancient-style marble capitals suggest a connection with work beyond the Apennines.7 While the monastery of Sant’Apollonio at Canossa, possibly founded between 1085 and 1090, is today certainly a ruin, as is the castle (Figure 2.3), there are still traces of Matilda’s decision, attested by Donizo, to place her ancestors there in Roman sarcophagi between 1111 and 1112. Four sarcophagi remained intact until 1392, as confirmed by an epigraph transcribed by the humanist Nicola Fabrizio Ferrarini from Reggio Emilia (Figure 2.4).8 The museum holds only some small fragments of ancient sarcophagi (Figure 2.5), the remains of those chosen by Matilda to bury her ancestors, as Donizo recalls in the prologue of his poem.9

The history of San Benedetto Po is complex. While nothing precise is known about Boniface’s monastery, the most significant architectural works were carried out under the abbots Guglielmo (1080–99), the Cluniac Alberico (1099–ante 1123) and Enrico (1125–41). The question of chronology is still debated and the latest reconstructions suggest an early date for the church of Santa Maria, modelled on Cluny, perhaps in the 1090s.10 This period may also have seen the start of work on rebuilding the major church, as is perhaps suggested by the evident misalignment of the plan. According to Piva, the scholar who has focussed most attention on the edifice, the layout with five radiating chapels is necessarily derived from Cluny III and therefore to be dated after the chapels of the ambulatory of that complex. The new abbey would therefore have been built under the abbot Alberico and related to Matilda’s donation of 1101. It is also known that the chapter house was completed in 1109. Together with the surviving three Months (Figures 2.6 and 2.7) and a fragment of a Nativity (parts of a portal with the months depicted in the jambs and the infancy of Christ on the architrave as in Piacenza), all this suggests a date to the first decade of the 12th century, as does comparison of the sculptures with those of the Modena Genesis.

The history of Modena Cathedral is too well known, documented and debated to return to here.11 Suffice it to recall the documentary evidence: the slab now in the façade that gives the date of 1099 for its foundation (Figure 2.8); the slab in the apse that gives the date of 1106 for its papal consecration; and the Relatio, which illustrates how and when the new cathedral was built and emphasizes the decision taken by the architect Lanfranco to transfer the body of St Geminianus from the old church to the new apse because the old building was at an angle to the new one and obstructed work on the north side and the interior.12 Importance also attaches to the two ‘lives’ of Geminianus in connection with the architrave of the side entrance known as the Porta dei Principi.13 Further elements gleaned from the Relatio include the various actors involved: ‘ordo clericorum … universus eiusdem ecclesie populus’, ‘cives’ and ‘ecclesiae milites’. Matilda was present ‘cum suo exercitu’. The translation of the relics was delayed for the arrival of Pope Paschal II and the guardians of the tomb comprised six ‘de ordine militum’ and twelve ‘de civibus’. Matilda therefore had her own men and took part in every phase of the translation, as she had earlier in the act of foundation and the opening of the sarcophagus. The problem that arises at this point is the relationship between Matilda and the city, which is also made evident by the presence of Bonsignore, bishop of Reggio Emilia, accompanied by Dodone, later bishop of Modena, where the episcopal chair had previously remained vacant.

Let us, however, consider another moment of Matilda’s relations with cities, this time Cremona, where the bishop Arnolfo da Velate (1068–78), appointed by the Emperor Henry IV, was excommunicated in 1078 by Pope Gregory VII. He was succeeded by the reformer Gualtiero (1086–87), after which the see was left vacant. Matilda formed an anti-imperial alliance with the cities of Milan, Lodi, Piacenza and Cremona in 1093. In 1097 she entered into negotiations with the capitanei as it appears that Cremona had had no bishop for about two decades and the pro-imperial Ugo da Noceto (1110–17) may never have been consecrated. The situation was therefore similar to the one in Modena. Giordano da Clivio, the pro-papal archbishop of Milan, deposed Ugo and installed Oberto da Dovara (1118–62) in Cremona. Matilda’s presence therefore appears to have been significant in the city for many years. In 1097, with a document drawn up in Piadena on 26 December, she yielded the important insula Fulcherii to Cremona in exchange for a political and military alliance.14 The agreement was entered into by the capitanei, valvassori and cives, the first two being feudal orders but not the third. In short, Matilda was deeply involved in events inside the city also in periods when the episcopal see was vacant. Work on the building of Cremona’s cathedral started in 1107, as attested by a slab held by the prophets Enoch and Elijah, now in the sacristy (Figure. 2.9). A partial collapse in 1117 was followed by rebuilding after an interval of time because the relics of St Himerius of Cremona remained ‘for a long time’ beneath the rubble, presumably at the end of the edifice where the crypt and saint’s burial place were situated.15

The case of the cathedral of Piacenza is equally significant (Figure 2.10). The pro-imperial bishop Dionigi (1048–77) took part in the Council of Basel of 1061, at which Pietro Cadalo, bishop of Parma, was elected pope (the antipope Honorius II). Dionigi then returned to the fold, as attested in a letter of Gregory VII dated 27 November 1074. Another reformer was Bishop Bonizone of Piacenza (1088–89), the author of the important anti-heretical text Liber ad amicum, who was expelled from the city by supporters of the emperor. After a period of two years about which nothing is known, the pro-imperial Winrico (1091–93) was installed in his place. Piacenza soon returned to orthodoxy, however, as confirmed by the arrival of Pope Urban II, who convened the synod there of 1095. The see was then held by Aldo (1095–1121), who followed the First Crusade to the Holy Land, and Arduino (1121–47), who built the cathedral of Santa Giustina and Santa Maria. It should finally be recalled that in 1106, at the Council of Guastalla, Pope Paschal II, proclaimed the independence of the dioceses of Parma, Piacenza, Reggio Emilia, Modena and Bologna from Ravenna, the see until 1100 of the antipope Clement III.16

The case of Parma’s cathedral is also important, the history of which I have already examined elsewhere. The strictly Lombard culture clearly visible in the apsidal section was transformed into a far more complex invention that also encompassed a vast presbytery enclosure attributable to Nicholaus and his assistants. I would regard this as connected with the city’s transfer of allegiance from the empire to the papacy and acceptance, as we have seen, of Bernardo degli Uberti as bishop in 1106.17

It appears evident from this overly schematic outline that in the various cases where the Gregorian Reform was introduced – the abbeys of Nonantola and San Benedetto Po, the cathedrals of Modena, Cremona and Piacenza, but also many other examples in the territories under Matilda’s control or influence – this was connected with the direct or indirect presence of the Great Countess, who granted prelates, unable to occupy their sees in cities like Modena and Parma, protection in her domains until it was possible to install them.

Let us now examine the locations of the new cathedrals, which are situated in all these cases – in Modena as in Cremona, Parma and Piacenza – outside the ancient Roman nucleus, thus making it possible to erect buildings of considerable size, though the growth of population is also a factor. This brings us to what connects not only these construction projects but also the monasteries of Nonantola and San Benedetto Po, namely the employment of a single sculptor, first Wiligelmo and then Nicholaus, and their workshops. The architects, on the other hand, varied, Lanfranco in Modena and Nicholaus in Piacenza and perhaps Cremona.18 The Relatio tells us the choice of Lanfranco as architect of Modena’s cathedral was divinely inspired: donante Dei misericordia vir quidam, nomine Lanfrancus mirabilis artifex mirificus edificator. The great skill exhibited by this ‘admirable artist and builder’ is indicated further on: erigitur itaque diversi operis machina; effodiuntur marmora insignia, sculpuntur ac poliuntur arte mirifica; sublevantur et construuntur magno cum labore et artificum astutia. Crescunt ergo parietes, crescit edifitium; laudatur et estollitur, summe Deus, tuum ineffabile benefitium. It thus appears clear from this text, written shortly after 1106, that the relationship between sculpture and architecture was very close indeed. The machinery (hoists and other devices for lifting and scaffolding) are immediately noted because they are varied and required moreover to bear heavy weights, of stone and not only of bricks. Ancient marbles were, in fact, reworked and sometimes even carved. There are many pieces of Roman marble reused in the building, as shown by a recent study.19 The construction thus grew not only in height but also in length. As stated in the Relatio, once the foundations had been dug, the walls were built above the level of the ground, and the building in longum protenditur. Two miniatures of the Relatio appear to bear traces, as I have previously suggested, of a vision conceived as horizontal from the outset, and perhaps derived from a scheme painted on the walls of the Cathedral.20 The proof, which escaped notice, is the continuity of the level of the terrain in the first three scenes, from the choice of the site to the digging of the foundations and the erection of brick quoins. The only space differently conceived is that of the inventio of the saint’s body with Bonsignore, the bishop of Reggio Emilia, helping Lanfranco to raise the slab. Dodone, bishop of Modena, is on the right in the second row and Matilda on the left holding a piece of fabric, possibly to wrap the body. The guardians of the tomb, cives and milites, are shown at the bottom in front of the sarcophagus.

Let us now consider the information provided by the political history of the various cities and seek to connect it with the foregoing observations. With the stories carved in the jambs of the portal in the abbey’s façade, Nonantola offers us a text by Wiligelmo’s workshop that presents innovative elements. The left jamb shows the life of the saint, Aistulf, Anselm and Pope Hadrian III; in short, the history of the origins of the abbey and its relics. The right jamb instead shows the infancy of Christ, thus demonstrating how long the sculptor’s book of drawings remained in use, as the same scenes are to be found in the north portal at Piacenza, dated around 1122 and attributed to the same workshop21 (Figures 2.11 and 2.12). In Nonantola and Piacenza alike, the first king in the Adoration of the Magi is kneeling whereas the three magi of the doors from Hildesheim and St. Maria im Kapitol in Cologne, for example, are standing. If the Virgin Mary was the symbol of the Church in the territories of the Gregorian Reform, kneeling before her, and hence the Church of Rome, takes on a precise political significance, and it is certainly no coincidence that this iconography was widespread throughout the west. The three surviving fragments of the portal with the Months, from San Benedetto Po. are connected, as we have seen, with those of Modena Cathedral and can be compared both with the panels of the Genesis and with the Prophets of the middle portal, and therefore assigned a date in the first decade of the 12th century. At this point, however, it becomes necessary to consider the chronology of the sculptures of the cathedral, which has recently been called into question once again. While most of the scholars from Porter on22 regarded Wiligelmo as active up to 1110 at the latest, a chronology extending as far as 1130 has recently been put forward for the cathedral built by Lanfranco and hence indirectly also for Wiligelmo’s sculpture.23

Apart from the difficulty of such a chronological span for a sculptor active from approximately 1107 to 1115 in Cremona, as we shall see, and documented at Nonantola around the beginning of the first decade of the century, we must ask what can have induced anyone to alter the chronology of the sculptures and so place Wiligelmo in the very different period of Nicholaus, a sculptor who was certainly his pupil but is markedly dissimilar in character. Some light may be shed by the long debate on the dating of the Porta della Pescheria, which was shifted by scholars like Émile Mâle to the mid 12th century.24 More recent critics have distinguished two independent traditions for the Arthurian subject matter: the oral traditions related to the Modena archivolt and the written tradition of the poem Historia regum Britanniae. The thesis put forward in the art-critical literature of the first half of the 20th century, as developed by Geza de Francovich, instead suggests a Burgundian influence on the entrance as a whole, on ‘Truth plucking out the tongue of falsehood’, on the metopes and on many capitals on the north and south sides of Modena Cathedral.25 While Roberto Salvini26 also accepts this hypothesis, which entails marked shifts in chronology,27 careful examination of the various pieces clearly shows that it is untenable and makes it possible to reassert the involvement of Wiligelmo in all the cases cited here. Comparison of the series of metopes – the two juxtaposed figures of the Antipodes, the figure with three arms and the Siren – with the images of Wiligelmo’s Genesis on the façade – Eve and other figures – clearly shows the homogeneity of the group, allowances being made for the marked abrasion of these stone capitals exposed to the elements (Figures 2.13 and 2.14). The same homogeneity is indeed also to be found in another supposedly Burgundian piece, namely ‘Truth plucking out the tongue of falsehood’, the anti-heretical meaning of which has recently been identified by Dorothy Glass.28 This again displays marked similarities with the capitals of the half-columns outside the cathedral. The block of Genesis sculptures, the capitals on the façade attributed by practically all the scholars to Wiligelmo, like the one with the Sirens, the metopes, the two lateral portals and the Porta dei Principi with scenes in the life of St Geminianus therefore fit perfectly into Wiligelmo’s period. The overall reading of the pieces of Modena Cathedral put forward by Frugoni, the reading of the metopes as images of the peoples of the earth29 and the interpretation of the Genesis panels put forward by Gandolfo30 all clearly demonstrate the anti-heretical character of the narrative. I shall not linger on this point.

Attention should, however, be drawn to the fact that the narrative system invented by Wiligelmo cannot have been confined to the exteriors of cathedrals or abbeys but must have extended to the interiors, which will entail a change in attribution. I suggested long ago31 that the pulpit of Modena Cathedral, now shortened and placed at the top of the façade, should be attributed to Wiligelmo (Figures 2.15 and 2.16).32 Despite its reduced state, that pulpit can be seen as the precise model of the pulpit of Cremona Cathedral, which is again incomplete; the Sagra of Carpi pulpit (Modena) (Figure. 2.17), which helps us to understand how the slabs could have been arranged, as the front and the two sides are intact; the pulpit of Quarantoli, unfortunately reduced and fragmentary; and the pulpit now in Sant’Agata di Sorbara (Modena), of which only one animal remains, the lion of St Mark, unfortunately devoid of its original cornice. While preferring not to go on and list other pulpits that I have repeatedly discussed in the past, I must emphasize the importance of this internal furniture, first of all because it entails central access to the area of the presbytery, wherever there is a crypt, and confirms the significance attached by the Gregorian Reform to the Gospel and the reading of the Gospel. The pulpit also prompts reflection on the symbolic function of the books that constituted the cornerstones of the Reform, namely the Giant Bibles, which were exhibited on high at key moments of the religious rites, on the pulpit or on the altar dominating the nave.

The sculpture of Cremona Cathedral constitutes an imposing complex if we add, to the pieces remaining in situ, the remnants of the large vine of the middle portal, a small pediment, a telamon and other elements, all now in the Museo del Castello Sforzesco, Milan, but originally belonging to the cathedral. (Figure 2.18) The many pieces still in Cremona include the remains of two pulpits and there are evident traces of the involvement of the sculptor of the Porta della Pescheria (Figure 2.19) and the Porta dei Principi as well, in my view, as Wiligelmo for the central gate. The debate on whether Wiligelmo worked in Cremona and whether the prophets (Figure 2.20) are by him or a workshop, which has gone on since the days of Arthur Kingsley Porter, is quite irrelevant, as everything appears in any case to confirm the presence of the Modenese workshop in Cremona from 1107 and before the earthquake of 1117. Nicholaus, Wiligelmo’s greatest pupil and continuer, may have worked in Cremona, possibly in a later phase. The portals of the façade of Piacenza Cathedral are attributed to the Cremonese workshop and the northern portal, as we have seen, to Wiligelmo, while the central and southern portals are the work of Nicholaus, who also produced some of the internal capitals, all dated between 1122 and 1132 or slightly later. In the end, the so-called School of Piacenza hypothesised by De Francovich33 is simply Nicholaus and his assistants.34

A programme connected with the Gregorian Reform is certainly present in the codices produced in this period, as well as in the body of designs of Wiligelmo and his assistants who worked on the various buildings mentioned here – from Nonantola and Polirone to Modena, Cremona and Piacenza, while it was Nicholaus above all that worked in Parma within the more traditional framework of Lombard sculpture. In these workshop designs the revolution in meaning is evident and connected with new figures or ancient images subjected to semantic transformation. Anti-heretical functions are thus conferred on Enoch and Elijah, Samson and the lion, Genesis, Noah and the ark. The telamones represent the suffering of sinners and the lions either Christ or the Holy Roman Empire. Further images include the above mentioned Adoration of the Magi, the pilgrim to be found also – as I have shown – in the Joseph on his journey into Egypt, the armed pilgrimage of knights returning from Modena to Bari to Parma as a reference to the fight against the infidel, and the dominant figure of St Peter in half of the west.35 In all the places where Wiligelmo and his assistants worked, we can discern a unified narrative that unquestionably derives from a precise project.

I shall now return to Matilda with some images from Donizo’s Vita Mathildis (Vat. Lat. 4922), a Vatican codex from the early 12th century.36 The first illustration (fol. 7v) shows Donizo presenting his poem to Matilda above the inscription Mathildis lucens precor hoc cape cara volumen. The elements comprise Matilda enthroned, a footrest, Donizo at a lectern to the left with the codex opened out, a red background signifying regal or imperial power, a mantle with a gold border, an aedicula and an armed figure on the right representing Matilda’s milites. The well-known miniature fol. 49r. bears the inscription Rex rogat abbatem mathildim supplicat atque: ‘the king implores the abbot and pleads with Matilda’.37 We see Abbot Hugo of Cluny to the left, seated on a sella plicabilis, the Emperor Henry IV on his knees and Matilda enthroned beneath a ciborium turned towards the two figures with her arms outstretched to the right. Various events are recounted here and the only figure missing is Pope Gregory VII, who refused to receive the emperor. The abbot is speaking to Matilda, as indicated by the finger, she addresses both of them, and the emperor is kneeling, as he was outside Canossa. We thus have a combination of different moments. In short, the images are always strongly symbolic and closely related to the text.

In his poem, Donizo constructs a geography of power through burials: of Matilda buried in San Benedetto Po; of Beatrice in Pisa near the cathedral, inside or outside; of Boniface, treacherously slain, in Mantua; and finally of the ancestors at Canossa in at least four sarcophagi, some fragments of which still survive. The tombs of the ancestors are, however, like those of saints, the ones enclosing holy remains inside the cathedral or abbeys, and the images of Donizo’s codex are therefore richly imbued with meaning. In fact, apart from Matilda’s parents, all the ancestors represented in the miniatures were buried at Canossa. The author thus suggests their presence as symbols of the length of the dynasty but also as figures close to the sanctity of the precious relics held in the monastery of Sant’Apollonio at Canossa. The miniature fol. 19r thus shows Adalberto Atto obtaining the relics of Sts Victor and Corona and of St Apollonius (Figure 2.21). The two inscriptions above read as follows: Corpora Sanctorum Rex Athoni dedit horum and Sancta Corona et Santus Victor. Membra secat Sancti Gotefredus dans ea patri: Godfrey, bishop of Brescia, thus severed the right arm of St Apollonius and gave it to his father. Our interest focusses on the image in the lower panel, where we see, on the right, a sarcophagus with a vine shoot suggesting antiquity, like the ancient but very simple sarcophagus of St Geminianus, the ancient sarcophagusi of Matilda’s ancestors, of Beatrice in Pisa (Figure 2.22) and perhaps of Boniface in Mantua.

In short, it is also burial in ancient sarcophagi that identifies the saints of the Gregorian Reform. Their relics alongside the tombs of the patrons and the geography of the burials is the geography of a political project that was to end with Matilda. It is a story in which holiness, feudal power and the astute politics of the lords of Canossa, of Boniface, Beatrice and Matilda, play an important part. The programmed image of the fight against the heresy of the antipopes and their bishops was conceived as a weapon of war not only in religious retreats but also within the opulent cities. Matilda was well aware of this, as were the intellectuals that worked alongside her, like Donizo in Canossa, and with them the cultured architects and sculptors Lanfranco, Wiligelmo and Nicholaus and their assistants.