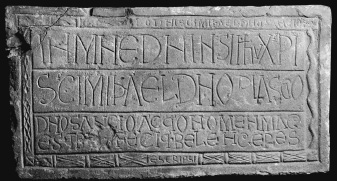

The pre-Romanesque church of San Miguel de Villatuerta in Navarre is known for its relief carvings, which, according to currently accepted opinion, represent the ceremony of the blessing of troops marching into battle.1 The ordo on which this is based dates from Visigothic times and underscores the principle of cooperation between bishops and kings in military ventures. The location of the reliefs seems to be related to the strategic importance of the site. It is halfway between Pamplona, the capital, and Nájera, the second city of the kingdom, near the ford where Abd-al-Rahman III’s troops had attacked in the years 920 and 924. The inscription (Figure 5.1) extols the importance of Bishop Velasco, who governed the diocese of Pamplona in the decade around 970.2 He is easily identified by his mitre and crosier and is mounted on a galloping horse. However, despite the mention of Sancto re, referring to Sancho Garcés II, King of Pamplona from 970 to 994, there is no equivalent representation among the roughly carved figures that can be identified with the monarch. It was the reliefs that saved this church from falling into oblivion. It wasn’t noted for its architectural innovation or aspirations and, as far as we know, produced no imitators. The reliefs reflect the military vocation that predominated in the nascent kingdom of Pamplona and united the destinies of the crown and the mitre. The much greater size of the text referring to the bishop in the inscription and the greater prominence of the figure of the prelate suggest that it was he who was responsible for its construction. In this respect, Villatuerta sets a modest precedent for the joint presence of kings and bishops in architectural projects in Pyrenean lands.

The introduction of Romanesque architecture in the eleventh century similarly involved cooperation between kings and bishops on important buildings. I will analyse this in detail by focusing attention on three buildings of particular significance: the Abbey of Leire (Navarre) and the Cathedrals of Jaca (Aragon) and Pamplona (Navarre).

Our perspectives on the origins of Romanesque in the western Pyrenees are clouded by the relative importance of the Kingdoms of Aragon and Navarre in the later Middle Ages. Before the year 1000 there were no examples in these lands of Christian buildings that were greater than 25 m long or were vaulted throughout. Given that backdrop, the interest shown by Pamplonese sovereigns in enlarging the abbey church of San Salvador of Leire (Navarre) takes on a special significance, as exemplified in a document recording a donation by Sancho IV to the monastery on the occasion of the 1057 consecration of its church (Figure 5.2).3 The young king, then just eighteen years old, had succeeded to the throne three years earlier, following the unexpected death of his father, García III while fighting Ferdinand I of Castile (Garcia’s brother). The donation commemorates the dead king and makes it known that the entire royal family was anxious to see the church finished.4 Bear in mind, however, that Sancho IV did not attend the ceremony as patron but as a guest of the bishop, John.5

Knowledge of the historical context suggests the enlargement of the church was due to the grandfather of Sancho IV, the famous Sancho III the Great (1004–1035), and not his son, García III (1035–1054). There are no chronicles or documents to link these monarchs with the building, and the monastery itself instead acknowledges the figure of Sancho III’s grandfather, Sancho II, who had probably been buried there. His imaginary coat of arms decorates a keystone of the Gothic vault.6 However, there is no doubt Sancho III had the motive, opportunity and means to promote such an ambitious construction. This cannot be said of his successor, who was more interested in Santa María de Nájera. But, did Sancho III actually intervene? And, if so, in what way did he participate?

In early studies on the architecture of Leire, authors such as Madrazo, Bertaux, and Lampérez dated the Romanesque east end (Figure 5.3) to the time of Sancho Ramírez (1064–1094), taking into consideration a second consecration documented in 1098.7 Gómez Moreno accepted this date, although he was aware that the architecture of Leire would be decidedly ‘retardataire’ for this chronology to work.8 It was José María Lacarra, the great historian of medieval Navarre, who, in 1944, linked the enlargement of the Romanesque church to Sancho III.9 His arguments included the character of the king, ‘a pro-European reformist monarch’, the important role played by the abbey in the kingdom of Pamplona at the beginning of the 11th century, and the 1057 consecration. Architectural renovation by Sancho III would have been ‘in parallel with the monastic restoration and political resurgence of the first third of the eleventh century’.10

Lacarra’s proposal was favourably received.11 Although advances in historical studies have cast doubt on other actions attributed to Sancho III, such as the introduction of the Cluniac Reform to the peninsula or extensive investment in the Way of Saint James, perceptions of his role in the kingdom’s architectural renewal have been enhanced, thanks to the detailed study of Leire’s crypt and church published by Francisco Íñiguez in 1966 and subsequent 1970 article on the king’s artistic patronage, studies which have achieved broad acceptance.12

Historical sources favour the hypothesis that the real driving force behind the enlargement was Abbot Sancho (1024–52), simultaneously abbot of Leire and bishop of Pamplona.13 He was a singularly interesting character.14 His life took a very different course from that of his predecessors, precisely because of the relationship he cultivated with Cluny, and he is the best candidate to be identified with the Sancius Pampulanorum episcopus mentioned by Odilo’s biographer, Jotsaldo, who goes on to say that Bishop Sancho enjoyed a special friendship with the abbot of Cluny, to the extent that Odilo remembered him in instructions he left on his death.15

By the beginning of the 11th century, the monastery of Leire was already more than a century old. Its church consisted of a short aisled nave and a triple-apsed east end, straight on the exterior and semicircular inside in the Iberian early medieval manner. There is no record of any Moorish raid in the early years of the 11th century which might have affected the monastery.16 Therefore, the 1057 ceremony will not have been the consecration of a church that had been burnt or defiled by enemies of the Christian faith. It will have marked the enlargement of a church that had become too small.

Sancho III will have been interested in Leire for two reasons. The first was a more general inclination towards monasticism: the Navarran texts of the Roda Codex, written shortly after his death, describe him as desiderator et amator agmina monacorum.17 The second was because Leire had acted as the main burial church of the Pamplonese royal family since the 9th century. It is very likely that Sancho III’s father and grandfather were buried there.18 However, neither tradition, nor detailed study of the building provides any additional information as to Sancho’s links with Leire, and involvement on the part of the monarch was probably limited to supporting the abbot’s initiative to enlarge the church. The economic viability of new construction work can only have been sustained by donations to the abbey and the recovery of rents from the diocese of Pamplona. In this case, the king did intervene.19 A telling example is found in an event that occurred in Zamarce, an enclave of ancient ecclesiastical land belonging to the cathedral, situated on the Roman road from Bordeaux to Astorga. According to a document dated 1031, the king convened the local elders to settle a dispute as to who owned the property. The meeting then decided in favour of the cathedral, vesting ownership in the bishop-abbot.20

Regardless of the arguments put forward by Íñiguez as to Sancho III’s involvement in a number of building projects, the architectural ambition evident in the eastern parts of Leire is unquestionably greater than that of any other ecclesiastical projects: the crypt of San Antolín in Palencia, the lower church of San Juan de la Peña and the enlargement of San Millán de la Cogolla. As Janice Mann observed, if their monumental appearance had anything in common (‘no single coherent formal language unites these monuments’), it was limited to their use of rounded arches and vaults, the fact they represent enlargements, and the respect they showed for existing buildings. That said, they share too few elements in common to be able to sustain the argument that they formed part of an architectural renewal consciously led by the monarch.21

The Leire enlargement was different. It signified a radical break with the previous modest architecture of the Kingdom of Pamplona because of its ‘grandiose sobriety’ (in the words of Georges Gaillard),22 as evidenced by the use of large blocks of ashlar for walls and vaults, and the clumsy treatment of solutions derived from more refined architecture, such as alternating pillars and columns or the proliferation of archivolts on the doorways. Cabanot has compared the poor ornamentation of capitals, mouldings and corbels with works from the other side of the Pyrenees (Figure 5.4).23 Could King Sancho III have seen buildings that inspired him to enlarge Leire? We have no record of this. His constant travels around the north of the Peninsula, from Ribagorza to León, did not take him to any church that we might recognise as a visual source for the monastic church. Nor, as far as we know, would he have seen a possible model on his celebrated 1010 trip to Saint Jean d’Angély.24

On the other hand, it does seem reasonable to attribute direct responsibility for the enlargement to Bishop-Abbot Sancho. Thanks to the co-operation of the king, who repeatedly referred to the prelate as ‘my master’ (perhaps also his chancellor), he managed economic resources far greater than those of his predecessors. His close relationship with Odilo, promoter of the monumental Cluny II, may explain his initiative for undertaking new work at Leire. This may necessitate a rethinking of the date at which work began, as a letter from Odilo to Abbot Paterno proves that Bishop-Abbot Sancho visited the Burgundian abbey after the death of Sancho III.25

The particularities of Leire’s fabric can reasonably be explained by the circumstances surrounding its commission. Faced with a challenge without precedent in the immediate neighbourhood of Leire, the abbot would have contracted a master builder with limited training, entrusting him with a monumental building inspired by the refined architectural techniques the Abbot had seen elsewhere. A desire for ashlar masonry in the peninsular tradition and the hardness of the local stone made this work arduous. In developing an elevation out of a well-tried plan, the master builder either overlooked conventional proportional relationships between supports and arches, or simply disregarded them, as well as disregarding consistency of treatment, because he attached no importance to either. Through lack of experience, he improvised both the windowsills, which were recarved, and the points where different surfaces converged, in spite of which, he still managed to achieve an imposing building. The east end at Leire takes us back to a time when patrons and builders risked embarking on projects when they had no previous experience. This attitude proved crucial for the rapid pace of architectural development at the beginning of the Romanesque period.

Since Antonio Ubieto demonstrated the forgery of the three documents sustaining the attribution, hardly anyone now believes the old hypothesis that King Ramiro I of Aragon (1035–1064) was responsible for Jaca Cathedral.26 Nevertheless, there are still historians who argue that Ramiro was responsible for an initial project which is conserved in the outline of the east end and the three lower courses of the northern apse.27 In my opinion, examination of the apse shows that this initial ‘Lombard’ phase, supposedly interrupted soon after it was started, never existed (Figure 5.5). The lower courses are of the same size as others we find in various parts of the church, and their type is similar to that of the upper courses.28

For more than fifty years, scholarly opinion on Jaca has followed Ubieto, Moralejo, Durliat, and Simon, among others, in basing assessments of Jaca on the (genuine) documentation, its historical context, analysis of the architecture and the study of the sculpture.29 All agree that the cathedral was begun during the reign of Sancho Ramírez, son of Ramiro I, some time after regional charters or fueros were granted to Jaca in 1077. It is perfectly conceivable that the church was finished during the reign of Pedro I (1094–1104), son of Sancho Ramírez. I therefore see no reason to conclude, as is frequently done, that the conquest of Huesca in 1096 caused a drastic interruption of the works. The refurbishment of the ancient mosque at Huesca in 1096, prior to its consecration as a Christian cathedral, lasted for no more than a few months. There is no obvious reason why it should have any consequences for construction at Jaca. There is also no evidence of a reduction in cathedral rents at Jaca, or a loss of interest in the city by its kings and bishops. The homogeneity of the sculptural decoration of the building, as shown by Gómez Moreno and Moralejo, supports the idea that a possible interruption – and a change of architect if there was one – would only have affected the upper parts of the central nave, built when the vaults of the east end and the transept were already finished.30 In a recent examination, I detected an interruption in the masonry above the vaults on the south side of the nave, which then continues downwards with courses of different sizes. The masonry joint was situated at an ideal distance for the original walling to have acted as a temporary buttress for the transept vaults.31

After the assassination in 1076 of King Sancho IV, his cousin, Sancho Ramírez, came to the Pamplonese throne (Figure 5.6). Until then Sancho Ramírez had governed Aragon as count, without using the title ‘king’ (in a genuine document of 1072 his title was given as gratia Dei aragonense without the word rex). This had consequences at all levels. Ubieto and Cabanes affirm that Sancho Ramírez immediately called himself gratia Dei rex Aragonensium et Pampilonensium, in reference to his authority and royal power over both territories, now raised to the same level of dignity as sovereign kingdoms.32 It is worth remembering that his father, Ramiro I, had paid homage and fealty to his own half-brother, the king of Pamplona, García III.33

Sancho Ramírez must have seen the advantage of having a city in the old Aragonese county, now raised to the status of kingdom, as a seat for the bishopric of Aragon. Thus, he changed the legal status of Jaca from that of a free and independent town to that of city. The 1077 fuero expresses this with great solemnity: ‘I, Sancho, by the grace of God King of the Aragonese and Pamplonese, hereby make it known to all men in the East, the West, the North and the South, that I wish to found a city in my town called Jaca.’34 Jaca, by virtue of a palace already a royal seat, thus became an episcopal see. By this date, the Infante García, brother of Sancho Ramírez, had succeeded to the bishopric of Aragon.35 García took another step towards the shaping of the cathedral see, in line with the winds of reform then prevailing in the Church. He established canonical life based on the Rule of Saint Augustine in a reform of the clergy responsible for San Pedro, the main church in Jaca. The change must have taken place between 1076 and 1079.36 This could have been the moment that the idea of building a monumental church that departed from local tradition first took hold, though it wasn’t until years later that we can be certain that work had started.

There is documentary proof that Santa Maria of Ujué (Navarre), whose architecture and sculpture indisputably derive from Jaca, was in building under the initiative of Sancho Ramírez in 1089.37 This gives a terminus ante quem for the start of the cathedral of Jaca. Another significant landmark was the donation ad labore (sic) de Sancti Petri de Iacha contained in the disposal of assets made by the Infanta Urraca, sister of Sancho Ramírez, before the death of the king in 1094.38 In this document the infanta refers to the bishop of Jaca as meo magistro and not as her or the king’s brother, so this probably took place after the death of Bishop Garcia in 1086. Consideration should also be given to one corbel of the east end (Figure 5.7), which Serafín Moralejo argued was carved by a member of the workshop of Bernardus Gilduinus at a time not too far removed from the consecration of the altar of Saint-Sernin in Toulouse in 1096.39 Refining the chronology of the cathedral in more detail is no simple matter. It can be deduced that construction began in the 1080s, but we don’t know whether this was before or after the death of Bishop-Infante in 1086. By way of conclusion, it is my opinion that the tower portico, which corresponds to a second project, was already standing before work began on San Pedro of Siresa in the 1110s.40 As such, it is likely that the cathedral was planned and mostly built, during the bishoprics of the Infante García (1076–1086) and his successor, Pedro (1087–1099), the latter probably a former monk from San Juan de la Peña.41

A graphic recreation of Jaca cathedral around the year 1100 shows a highly distinctive church, characterised by a triple-apsed east end (Figure 5.8), a vaulted non-projecting transept, a ribbed crossing dome, and an aisled nave roofed in timber and reinforced by stone diaphragm arches (Figure 5.9), the remains of which have been recently discovered.42 David Simon argued that the original interior was deliberately evocative of early Christian basilicas and suggested it may have been the outcome of a relationship that King Sancho Ramírez first established with the papacy on his journey to Rome in 1068 and which was re-established around 1087–1089.43 In my opinion, Jaca is the Hispanic construction that best succeeds in recreating the architectural volumes and decoration of a Late Antique basilica and most strongly expresses the idea of the cathedral as a symbolic memorial to early Christian buildings – an association that Hélène Toubert, Valentino Pace and Arturo Carlo Quintavalle have applied to contemporary Italian buildings that were a product of Gregorian Reform.44

Nonetheless, the architecture is not the only key which might unlock the intentions behind the cathedral, nor reveal the identity of its principal patrons. Various scholars agree that the forms and themes of the sculpture at Jaca link it to royalty. The rich visual discourse represented by its tympana and capitals was organised in terms of political allegory. While not wishing to quote every author who has written on the subject, let us first remind ourselves that Dulce Ocón, Ruth Bartal, David Simon and Francisco de Asís García have all explored the relationships that link the Jaca chrismon (Figure 5.10) and Constantine’s Labarum with respect to the warring vocation of the kings of Aragon.45 Moralejo highlighted the donation that Sancho Ramírez made to Saint-Pons-de-Thomières in 1093, in which he compared himself to Abraham since he was also giving up his son Ramiro to God.46 And Simon identified the presence of Moses on a capital on the west doorway (Figure 5.11) and related it to a papal bull addressed to Bishop García by Gregory VII, in which the pontiff called the king of Aragon a ‘second Moses’ for having introduced the Roman Rite (an act the Pope mistakenly attributed to Ramiro I).47 Not only do I agree with this last identification, I would add that the side of the capital resembles the image of Gemini in San Isidoro of Leon.48 Perhaps the capital was intended to draw attention to a parallel between the receipt of the Law by the brothers Moses and Aaron, and cooperation between the brothers, Sancho Ramírez and Bishop García, in introducing the Lex Romana and the rule of Saint Augustine to Jaca Cathedral.49 Meanwhile, the choice of Abraham and Balaam as themes for the south doorway put Moralejo in mind of the descriptions of the Ishmaelites and Moabites used in the documentation of the time to refer, respectively, to the Moors and the Almoravids.50 Finally, if we accept Moralejo’s hypothesis concerning another capital on the west doorway, which he identifies as Daniel and the Priests of Baal (Figure 5.12), we can see an allusion to the punishment of clerics who treat church assets as their own, a priestly vice that was explicitly condemned in the document describing the introduction of regular canonical life to Jaca.51

Thus, in contrast to Leire, Jaca encompasses a number of images that represent the king’s thoughts on his role in the world, in both a military and a religious context. The signs and Old Testament scenes show in allegorical form what the king believed was his destiny as a vassal of God and the leader of a kingdom at war with the enemies of the faith. At first sight the emphasis on royal prerogatives and views would appear to relegate the bishop and the canons to a secondary role. In which case it would make no practical difference which prelate held the office of bishop, and the king’s plans should not have been affected by conflict with his brother, Bishop García, in the years between 1080 and 1086.52

This said, the figurative programme of the cathedral is above all a religious one. Moreover, neither García nor Pedro always bent to the will of Sancho Ramírez, just as the king did not always uncomplainingly obey the pope. In a letter probably written in 1080, Richard, abbot of Saint-Victor of Marseille, one of Pope Gregory VII’s legates, accused the king of seeking in his works the favour of men above the fear of God and salvation of souls.53

The inscriptions on the west tympanum unmistakably convey a religious intent. The chrismon that dominates this western entrance is not a sign of military victory – the coeleste signum Dei that, according to Lactantius, Constantine had put on the shields of his troops – but a Trinitarian sign of God: HAC IN SCULPTURA LECTOR SIC NOSCERE CVRA P PATER A GENITUS DUPLEX EST SPIRITUS ALMUS HII TRES IURE QUIDEM DOMINUS SUNT UNUS ET IDEM. Likewise, although their royal connotations cannot be denied, the lions that flank the chrismon here stand as the image of Jesus Christ: PARCERE STERNENTI LEO SCIT XPISTUSQUE PETENTI and IMPERIUM MORTIS CONCVLCANS EST LEO FORTIS. Taken as a whole, in accordance with the inscription underneath – VIVERE SI QUERIS QUI MORTIS LEGE TENERIS HVC SUPLICANDO VENI RENVENS FOMENTA VENENI COR VICIIS MUNDA PEREAS NE MORTE SECVNDA – the west doorway preaches Trinitarian dogma, the strength and mercy of Christ and the need for personal conversion for the salvation of the soul. It is a clerically formulated message destined for the faithful, one of whom was the monarch.

We are faced with a question of representation and connotation. The connotations relating to royalty are subordinate to the visual expression of the empire of God, and to the urgent task of establishing in society a life in keeping with the Gospel alongside the need for clerical reform, two of the ethical pillars of reformist popes and bishops. The religious connotations exist on a level with the monarchical ones. For example, episcopal authority can be seen in the relationship between the figure who prostrates himself at the feet of the lions and the ritual of public penitence, the episcopal prerogative practised in Aragonese dioceses up to the sixteenth century, as described by Antonio Durán Gudiol.54 The figure who, according to this rite, stood in the position of the tympanum lion, with the penitent at his feet, was the bishop himself. Likewise, the virtue of humility is here exalted, as represented by the abasement of the prostrate figure. Simon reminds us that the serpent that this figure holds in his right hand also symbolises humility, manifest by its crawling and the constant shedding of its skin.55

The programme of the south doorway has attracted less attention, unsurprisingly given the drastic modification of the tympanum. However, Moralejo’s reconstruction (Figure 5.13) is largely convincing, even though it is incomplete and his drawing does not entirely comply with what has been conserved.56 The portal would have originally depicted a Christ in majesty, surrounded by symbols of the Evangelists. In order to support the lower semicircular stones, a trumeau would have been necessary, which, according to García, carried the David capital.57 To either side are capitals dedicated to the sacrifice of Abraham and Balaam’s Ass (Figures 5.14 and 5.15). In religious thinking, the doorway denotes the supreme sovereignty of Christ (greater than that of earthly kings), the transmission of doctrine through the Gospels, and the virtue of obedience. Abraham obeyed God when faced with an incomprehensible command. And the diviner, Balaam, sent by the king of the Moabites to curse the troops of Israel, that is, the troops of the Lord while they wandered through the desert, finally obeyed God, who sent his angel to stop the donkey. At the feet of Christ, David leads the song of praise to the Lord, accompanied by the Levites.

Christians are here seen as sons of Abraham because of their faith (as opposed to Muslims, known at the time as Ishmaelites, who were descended from the illegitimate lineage of Abraham), and Balaam as the diviner who ends up praising the Lord of the Israelites (the same Lord as for Christians) also correspond to the realm of political allegory. Indeed, the exaltation of humility exhibited at both doorways deserves a political interpretation. As Cowdrey pointed out, for Gregory VII obedience and humility were virtually synonymous. ‘At his heart was obedience to the law and to the righteousness of God and to the admonitions of those upon earth who were his accredited spokesmen – especially to the Roman church and to the pope. (…) In Gregory’s eyes, humility was, above all, the distinguishing virtue of a good king. (…) If King Saul was his exemplar of disobedience to the world of God (…) King David showed how humility won the favour of God. Another exemplar of humility was the Emperor Constantine’.58

The evident congruence of Jaca’s programme and Gregory VII’s views on the characteristic virtues of kings and emperors reveals the extent to which Jaca was imbued with reformist ideology. The abundance of scenes from the Old Testament is one of the repeating patterns found in programmes connected with the Gregorian Reform.59 A Benedictine component is also visible. Chapter five of Benedict’s Rule, the first to spell out the virtues of the monk, is dedicated to obedience. It begins by affirming that ‘the first degree of humility is obedience without delay’, while chapter seven defines humility, and is by far the longest chapter of the Rule.

The programme at Jaca is therefore the product of a cultivated mind that knew the Scriptures in depth, fought to defend papal and reformist principles, and may have had a Benedictine background. Would this profile fit the king or a member of his entourage, the bishop, or a member of the chapter? To deal with the king first, the actions of Sancho Ramírez with respect to the papacy and the Church cannot be described in terms of submission and the defence of reformist principles at any cost. Over the three decades of his reign, Sancho adapted to circumstances and attempted to benefit the kingdom and himself ahead of the Church, or at least achieve a mutual benefit for himself, the kingdom and the Church.60 He was not a staunch defender of ecclesiastical independence with respect to temporal power, as was demonstrated in numerous episodes. One involves another Sancho, bishop of Aragon (1058–1075), who, according to a letter from Gregory VII, went to Rome to ask the pope to accept his resignation due to ill health. His resignation was refused because the two clerics that were proposed as replacements, both with the blessing of King Sancho Ramírez, were sons of concubines and did not fulfil the requisite canonical conditions.61 It clearly mattered little to the king that he despatched his bishop with proposals that went against the spirit and letter of the reform. A second episode involved the bishopric of Pamplona. Following the death of Bishop Blasco Gardéliz in 1078, the king put first his brother and then his sister Sancha in charge of the bishopric.62 This was completely at odds with the Church’s independence with respect to civil power. We could continue with numerous examples of religious rents being exploited by the monarch himself, or by Aragonese nobles with the king’s blessing. The above examples shed reasonable doubt on Sancho Ramírez’s intervention in the design of a programme that mainly focused on the conversion of the faithful and was expressed in texts and images of a clearly ecclesiastical nature.

Little can be said about Jaca’s chapter between 1080 and 1090 as we do not know the intellectual background of its members. Durán Gudiol cites a 12th-century memorial to the effect that after the death of the Bishop García ‘the canons of Jaca (…) hoped to avoid a bishop-monk being imposed on them’ which in the end was what happened.63 In my opinion, this also rules them out as creators of a programme with so many reformist and monastic connotations.

As for Bishop García, his background would have attuned him to the king’s objectives and royal image. He was appointed by the king, apparently without the blessing of the papal legate (which again casts doubt on the unswerving loyalty of both brothers to the reform movement). His main contribution to reform was to establish a communal life – comunem vitam … secundum institucionem sancti patris nostri Augustini – for the chapter at Jaca around 1076–1079.64 But, as well as being a papal objective, chapter reform was part of the ecclesiastical policy of previous Hispanic monarchs, such as Ferdinand I, King of Castile and Leon and uncle of Sancho Ramírez. This had been agreed in the first canon of the Council of Coyanza in 1050, convened by Ferdinand ad restaurationem nostrae Christianitatis.65 A final factor that weakens García’s potential as a formative contributor to the cathedral, at least to its figurative programme, is the confrontation he had with his brother, King Sancho Ramírez. The first sign of disagreement can be traced back by to a letter from the papal legate Ricardo to Sancho Ramírez dated 1080 (although according to an account in a 12th-century memorial the events took place in 1082).66 Durán contends that this confrontation reached a critical stage in 1083, when the king commanded his brother the bishop cum magna conminatione not to return to Alquézar if he ‘valued the eyes in his head’. In 1085, at the siege of Zaragoza, Alfonso VI of Castile and Leon, Sancho Ramírez’s adversary, even promised García the bishopric of Toledo, which, had it been accepted, would have entailed the bishop’s departure from the kingdom of Aragon, along with his entourage. The brothers finally settled their disagreements in 1086, shortly before García’s death.67 After this, the papal legate, Frotardo, hastened to install Pedro as bishop in Jaca, where he occupied the cathedra until 1099.68 In short, it is impossible to see Bishop García as a champion of reformist thinking as it was envisioned by Gregory VII between 1073 and 1085.

What we know of Bishop Pedro very much corresponds to the profile we have drawn out from the programme. There is no doubt that he supported the principles of the Gregorian Reform. He was directly appointed by the papal legate Frotardo, one of its fiercest proponents. It has also been suggested that Bishop Pedro was previously a monk from the Benedictine monastery of San Juan de la Peña, which was at the forefront of the reformist movement in Aragon. It was there that the Roman Liturgy had been introduced in 1071, liturgical unification being another objective of the reformist popes.69 In 1084, Abbot Sancho sent an expedition to Almería to search for the relics of Saint Indalecius, one of seven ‘apostles’ who, according to legendary accounts known by Gregory VII, preached the Gospel in the Iberian Peninsula.70 This initiative formed part of the reformist desire to return the Church to the times of Christ and his immediate successors; in a list of 12th-century relics from San Juan de la Peña, Saint Indalecius was identified as ‘one of the sixty-two disciples of Jesus Christ’.71 The capital with Daniel and Habakkuk from the enlargement of the church consecrated in 1094 demonstrates that San Juan de la Peña and Jaca cathedral shared sculptural forms and content in the late 1080s or early 1090s.72

If Bishop Pedro was the master iconographer and designer of the programme, then Sancho Ramírez’s role in the figurative programme of Jaca Cathedral moves to the other side of the mirror. The tympana and capitals would not be political allegories proposed by the sovereign but for him. The monarch’s documents were full of expressions of submission to God and the saints. As a good Christian, he was concerned for his final destiny. So, the proposed political allegories and images of humility and obedience would be well received, especially in the years in which the king renewed his vassalage to God and Saint Peter (around 1087–1089).73 Moreover, Bishop Pedro was acting in the name of the legate, Frotardo, whose influence on Sancho Ramírez has been noted by Paul Kehr.74 However, we cannot rule out the possibility that the king had previous knowledge of the programme and had given his blessing to it. A potentially harmonious relationship with Bishop Pedro and the cathedral clergy in everything that concerned religious worship in the cathedral could be the idea behind the south doorway capital of David and the Levites (Figure 5.16), for the Levites accompany the king on ‘instruments which (the king) made for giving praise’ (1 Chr 23, 5). One way or another, Sancho Ramírez probably did more than simply provide the financial means for finishing the great cathedral, something he yearned to do for ‘his’ city, Jaca, and his expanding kingdom.

To conclude, let us return to the arguments used to link the documents of Sancho Ramírez and Pedro I with the chrismon and with the capitals of Moses and Abraham. Could the texts have been the effect rather than the cause of the sculpture? The donation to Saint-Pons-de-Thomières, which compares the king to Abraham, dates from 1093, while the verbal equivalent of the tympanum of the chrismon can be found at the beginning of the endowment documents of San Juan de la Peña on the day of its consecration, the fourth of December, 1094.75 Although the Trinitarian Invocation is a recurring theme in Aragonese and Pamplonese documentation in the 11th century, the 1094 consecration preamble glorifies in the mystery of the dogma like none other: In nomine sancte et individue Trinitatis, inmensa et alma Trinitatis, qui est Pater et Filius et Spiritus Sanctus, una et coequalis esentia, sub divino imperioque Domini Nostri Ihesu Christi. Both mentions open the way to speculation on the impact the Jaca doorways might have had on their contemporaries. At the same time, they raise a case – not a very solid one, I’ll admit – for the building of the doorways at around this time. With respect to Gregory VII’s comparison between the King of Aragon and Moses, let’s remember that this is contained in a letter addressed to Garcia as Bishop of Jaca, not the king.76 As it was kept in the cathedral archives, Bishop Pedro could have known about it and taken it into consideration when this part of the programme was designed.

Various reliable documents refer to the intervention of Kings Pedro I (1094–1104) and Alfonso I the Battler (1104–1134) in the construction of Pamplona Cathedral, in addition to Bishops Pedro de Rodez (1083–1115), Guillermo (1115–1122) and Sancho de Larrosa (1122–1142). These provide chronological milestones that mark the process and progress of building: a papal bull from Pope Urban II speaks of the new building project in 1097; the work was mentioned in a royal document in 1099; an inscription on a doorway alluded to the beginning of construction in 1100; the bishop made donations to the architect for his good service in 1101 and 1107; and Paschal II exhorted the king to help finish the cathedral in 1114.77 Consecration of the cathedral took place in 1127.78

There seems no doubt that direct and almost exclusive responsibility for the project was taken by Bishop Pedro de Rodez (Pierre d’Andouque). His name alone appears on the documents that mention the architect Esteban. Educated at Conques and Saint-Pons-de-Thomières, Pedro took the crusader vow at Clermont in November, 1095 and was present in Toulouse at the consecration of Saint-Sernin by Urban II in May, 1096. He therefore had first-hand experience of some of the great churches then under construction north of the Pyrenees, and he would later go to Santiago de Compostela where he consecrated one of the chapels of the ambulatory in 1105.79 It is perhaps as a result of his wider knowledge of building that he embarked on a cathedral of such magnificent scale at Pamplona: more than 70 metres long and more than forty metres wide at the transepts (Figure 5.17).

As for King Pedro I, in addition to Urban II’s 1097 missive, in which the king and his subjects were exhorted to help in the cathedral’s construction, one reference seems to have been rather neglected in the recent literature. Pedro donated a piece of land by the river Salado for the purpose of building a mill ‘for the construction of the said church of Santa María’.80 Otherwise, according to Ubieto’s itinerary, the king was in Pamplona just once after 1100, in December, 1103, which rather rules out the notion that he was closely involved in work on the building.81

Pedro de Rodez was the first bishop of Pamplona who is known to have come from outside Navarre, Aragon or La Rioja.82 As at Jaca, the bishop reformed the chapter (in 1086, before he undertook the building of the new church). Another similarity is that he was appointed bishop in the time of Sancho Ramírez by the papal legate Frotardo, who had been his superior at Saint-Pons de Thomières. He was a supporter of the Gregorian Reform and was described by Urban II as ‘a religious man of venerable life.’83 Pedro began building at Pamplona with the construction of the canons’ residence, a structure which has partially survived to this day.84 This was finished in 1097 and it combined masonry typical of local stonemasons with portal sculpture reminiscent of Toulouse (Figure 5.18). He then began construction of the cathedral, a visual manifesto for a reform upon which the diocese had embarked – led by French clerics. José Goñi Gaztambide talks of the ‘Frankish ecclesiastical invasion’ when referring to Pamplona’s chapter of canons in the time of Pedro de Rodez, when up to fifteen figures originating from the other side of the Pyrenees can be identified.85

Unlike the radically innovative character of Leire and Jaca, Pamplona Cathedral was a variation on architectural formulas that were spreading on both sides of the Pyrenees at that time. The foundations were uncovered during excavations between 1990 and 1992.86 The east end consisted of three separate apses. The lateral apses opened onto the centre of the respective arms of the transept, while the principal was polygonal on the exterior (with seven faces) and semicircular on the interior, in which we can recognise a variant of the design of the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela.87 The west doorway consisted of two openings and eleven columns, as with the Portico de la Platerías at Santiago (Figure 5.19). The five capitals that have been conserved confirm the direct relationship with the Galician cathedral. The surviving sculpture is insufficient to determine whether the representational wealth and narrative complexity found on the portals at Santiago was imitated at Pamplona. Nevertheless, enough survives for us to conclude that the details of the project could reflect the architect’s training, while the architectural ambition expressed on a broader scale could originate from guidelines laid down by the bishop.

How was the money needed for such a massive church acquired? It is not known how the monarchs responded to papal requests for help in its construction and there is hardly any record of extra rents offered by those holding power, except for a donation from Urraca de Zamora, daughter of Ferdinand I, in 1100.88 Bishop Pedro knew how to collect large amounts made up of small contributions by the faithful, who, in return, were given the right to be buried in the cloister.89 A noteworthy benefactor of the new church was the confratria or brotherhood, specifically mentioned in the papal exhortations of 1097 and 1114 as receiving the absolution and blessing of the pontiffs in return for helping to build the church.90 This clearly doesn’t refer to the chapter since the documents cite the canons by name (clericorum regulariter uiuencium/canonicorum regulariter ibi uiuentium), but refers instead to a group with open membership (quicumque in prefati ecclesie confratria fuerint annotati) whose collaboration was probably limited to the sphere of finance. Unfortunately, there are no further references in Pamplona to this medieval form of ‘crowdfunding’, possibly imported by Pedro de Rodez from building projects outside the kingdom of Navarre. Brotherhoods dedicated to the construction and maintenance of Romanesque churches are recorded somewhat later in other parts of Navarre, as at Roncesvalles, Estella and Eunate, which presumably followed the cathedral model.91

To summarise, with respect to the establishment of Romanesque architecture in the kingdoms of Aragon and Pamplona, there are three crucial buildings where one can see the interests of kings and bishops coming together. Given the mutual benefits implicit in the new constructions, interaction was close and continuous. However, the projects did not fully integrate crown and mitre because:

The research published here formed part of the project ‘Arte y reformas religiosas en la España medieval’, financed by the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad HAR2012–38037. I would like to express my gratitude to John McNeill for his careful consideration of my paper and for his many valuable remarks improving it.