Figure 6.1

The town of Santiago de Compostela in the 12th century

The Romanesque cathedral of Santiago de Compostela was begun under the episcopacy of Diego I Peláez between 1075 and 1078 and brought to near completion under Archbishop Diego II Gelmírez.1 The Liber Sancti Jacobi records the year 1122. The Liber reads, ‛And since the first stone of its foundation was laid up to that in which the last was put in place there were forty-four years.’2 But no consecration date from this period has been passed down. Gelmírez died in 1140. In 1168 Master Mateo was employed by King Fernando II to design and execute a significant modification of the western part of the cathedral.3 The date in the inscription on the lintel of the Pórtico de la Gloria reads 1188.4 Again, however, we do not know what the date means. Does it only relate to a single event – putting the lintel in its proper place – or does it refer to the architectural completion of the porch? According to a royal charter and the consecration crosses inside the church, the consecration occurred in 1211.5 If we add all the years together, the cathedral appears to have been more or less a construction site for a period of 136 years. Within this time span eleven bishops governed the diocese, one queen and four kings ruled the country. With respect to the Romanesque cathedral, we may limit ourselves to the years between 1075/78 and the death of Archbishop Gelmírez in 1140. Within this span, many dignitaries and several institutions asserted different aims and interests regarding the cathedral: three bishops, Diego Peláez, Dalmacio and Diego Gelmírez; the dignitaries of the cathedral chapter; the convent of Antealtares; the kings and the queen of Castile-León Alfonso VI; his daughter Queen Urraca and her son King Alfonso VII; and not least the citizens of Santiago de Compostela.

I am approaching the question of patronage from a different angle, by focussing on the object and the period from 1075 to 1140, asking which persons supported the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela over that period of time or even refused – sometimes only temporarily – to support the enterprise for specific reasons. I wish to point out the conflicts, changing interests and alliances of the different protagonists as potential patrons in a broader sense. The result is a quite vivid mosaic of claims, interests and expectations that would not emerge if one would focus merely on one individual, like Diego II Gelmírez.

The following analysis is based on a re-examination of the three important historical sources, the Concordia de Antealtares,6 the Liber Sancti Jacobi7 and the Historia Compostellana,8 in the light of the most recent archaeological investigation undertaken by a research group from the Technical University of Cottbus, Germany under the direction of Professor Klaus Rheidt.

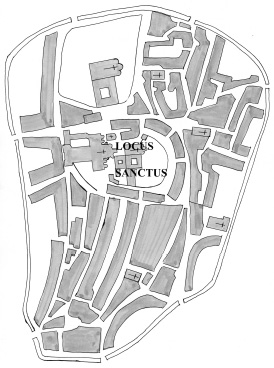

For a better understanding of the historical development it is important to know the spatial situation around the years 1075/78 when, according to the story in the Liber Sancti Jacobi, the first foundation stone was laid.9 It is of significance that the later town of Santiago de Compostela has its origin on the very same spot later called ‘locus sanctus’ – the Holy Place (Figure 6.1).10 The heart of the early settlement was not, as may often be observed in medieval history, a market-place or the crossing of trading routes, but a holy place, a spiritual site believed to be the burial place of St James. The old church from the end of the 9th century (Figure 6.2, no. 1) was of quite moderate size. The building was repaired after the pillage of Al Mansur in the early 11th century. The extent of the Romanesque cathedral is outlined with only a black line to illustrate what the new cathedral meant for the spatial situation of the buildings around the old church of St James. In front of the church towards the northwest, the Crónicon Iriense as well as Historia Compostellana mention a small building (Figure 6.2, no. 2) which was called the hospice.11 It was founded by Bishop Sisnando I († 920) and established for the poor, men and woman alike. The Crónicon Iriense does not mention expressis verbis pilgrims. The building had to be razed to make room for the new Romanesque church. Strictly speaking, the hospice stood on the site upon which Gelmírez erected his new palace some time around 1120.12 But no archaeological evidence of the hospice survives. Northeast of the old church of St James, situated between the church and the wall surrounding the locus sanctus, stood another church, Santa María Corticela (Figure 6.2, no. 3). The convent of Santa María Corticela was the predecessor of the monastery San Martín Pinario.13 The church was founded in the early 10th century under Bishop Sisnando I. The narrow space did not allow for a cloister and claustral buildings. Thus, the convent received an area north of the wall, outside the locus sanctus, where the monks could erect the required monastic officinae. Bishop Mezonzo († 1003) gave permission to build a small oratory next to the claustral buildings outside the locus sanctus. The extension of the new cathedral, in particular its eastern portion, made it necessary to shorten the nave of the Corticela church. One can assume that it was only a question of time before the monks would demand a proper monastic oratory next to their cloister, and Bishop Diego II Gelmírez, who ruled between 1100 and 1140, dedicated this new monastic church in 1106.14 The third institution, which is the oldest and the most significant, was located behind the eastern part of the old church of St James. It was the Benedictine monastery of Antealtares (Figure 6.2, no. 4). Whereas the other two institutions could very easily be relocated outside the locus sanctus, this was impossible in the case of the monastery of Antealtares. Antealtares affected the construction of the new church of St James mainly in two ways: firstly in spatial terms, and secondly in liturgical terms.

The first important document shedding light on the beginning of the new building of the church of St James is the so called Concordia de Antealtares. The text has survived in a parchment copy from 1435, written by Fernán Eanes. This charter informs us about a controversy between Diego I Peláez, bishop of Iria Flavia, and Fagildo, abbot of the monastery of Antealtares. The document is an agreement settling a dispute between the bishop and the abbot. This agreement was achieved in the presence of Alfonso VI, king of Castile-León in 1077.15 At this time the bishop still had his main residence in Iria Flavia, today’s Padrón, a small town on the Atlantic coast, and the church of St James had not yet been elevated to the status of a cathedral. Furthermore, it was not the bishop and his chapter who held their daily liturgical services in the church of the apostle, but the monks of Antealtares.

According to the narrative part in the Concordia de Antealtares we are told that in the first half of the ninth century King Alfonso II gave the instruction to build the first church over the tomb of St James.16 He also established a monastery adjacent to the east end of the mausoleum of the apostle. The main duty of the monks was to hold their liturgical services in the church and to tend to the tomb of the saint. The relation between the church of St James and the monastic church of Antealtares shown in Figure 6.3 illustrates only the information given in the Concordia de Antealtares. There is neither any archaeological evidence whatsoever for the size of the two buildings, nor do we know how closely the buildings were positioned in relation to each other. At the end of the 11th century, as the prestige of the saint increased, it also enhanced the reputation of the monastery of Antealtares. Performing the liturgical services at the altars was not only a question of reputation for the monks, but also a question of revenue, since the monks received a share of the income from the altars of the church of St James.17

The initiative of rebuilding the old church may have been launched by Bishop Diego I Peláez, with the approval of King Alfonso. But with regards to patronage, we must consider the term in a more general sense, that is: the bishop, the king and the convent of Antealtares. And this brings us back to the conflict already mentioned above. The Concordia de Antealtares states very explicitly that the space eastward of the mausoleum, separated in the image by a broken line (Figure 6.3, no. 6), belonged to the convent, and should still belong to the monks when the new east end of the Romanesque cathedral had been completed.18 In other words, the chapels of St Peter, St John and the central Saviour chapel had been constructed on the grounds of the monastery. Furthermore, the convent was granted permission to build a door near the chapel of St John to serve as direct access for the monks to the new presbytery of the Romanesque cathedral. Finally, the convent was granted a fixed share of the income from the altar of St James.

The scale of the Romanesque cathedral made it necessary to raze the abbey church of Antealtares. We know from the Concordia de Antealtares that Abbot Fagildo, not the bishop, had a small church built at his own expense as an interim arrangement.19 In 1077 the abbot still believed that he and his convent would be able to return to the church of St James. What we do not know are the promises made by the bishop to abbot and convent. Did the bishop intend to merge both churches, or did he promise the community a new monastic church, provided by him and his chapter? The two capitals on either side of the entrance of the central chapel of the new presbytery make it clear what future generations should believe. The capital on the north side shows Bishop Peláez between two angels (Figure 6.4). A similar composition was chosen for the capital on the opposite side, depicting the king of Castile-León, Alfonso VI (Figure 6.5). The inscription ‘Tempore presulis Didaci inceptum hoc opus fuit’ tells us that the work was begun during the episcopacy of Diego. Diego Peláez, however, was displaced by the king at the Council of Husillos in 1088 on charges of high treason and arrested. He died few years later.20 The inscription for Alfonso – ‘Regnante principe Adefonso constructum opus’ – informs us that the work was constructed during the reign of Alfonso VI, who died in 1109 and was buried in the Benedictine abbey at Sahagún.21 The church was definitely not finished in 1109. We may safely assume that opus is to be interpreted as the presbytery only. More important to me seems the depiction of Alfonso and Diego. Neither the king nor the bishop wears typical royal or liturgical dress. They are depicted without pontificalia and the complete set of regalia respectively. Both are accompanied by angels who lift them up towards the Kingdom of Heaven. The two angels on either side of Diego as well as Alfonso seem to be an allusion to the ascension. While the body of Diego Peláez is only roughly indicated, King Alfonso wears a kind of diadem and a large cloak which is tied up in front of his chest like a key. In terms of medieval iconography the depiction of the bishop could be interpreted as his soul. This would mean that Peláez had already deceased when the capital was carved. But in the case of the king, who wears a diadem and a large cloak one may think of Elijah and Enoch. Both had the privilege to enter the Kingdom of Heaven without dying. Thus, Alfonso is shown as a self-confident and powerful donor.22 The Concordia de Antealtares and these figurative capitals are the first important signs in the process of expropriation and damnation of the convent of Antealtares. The damnatio memoriae of Antealtares is still perceivable in modern scholarship, as John Williams recently pointed out.23

With respect to the building history it is important to note that at the time the Concordia de Antealtares was sealed in 1077 the three easternmost chapels were already under construction.24 Furthermore, we know from Klaus Rheidt’s research that the bottom stone courses of the foundation of the northern tower of the later Romanesque west façade perfectly aligned with the old church of St James as well as with the central eastern Saviour chapel.25 We do not know exactly when the foundations of the western towers were laid. But it is possible to date these building activities in close proximity to those of the eastern portions. If this proves true, we may assume that the design of the new church building was nearly complete from the very beginning, at least in its ground plan and its structural and spatial disposition (Figure 6.6): a three-aisled nave; a three-aisled transept with three chapels on the eastern side of each transept arm; a presbytery with ambulatory and five radiating chapels, with columns, piers, towers, staircases; and finally, the two-storey elevation with a circular gallery. Although there were changes to the design in the presbytery above the gallery level, one could suppose that even at this early stage a rough idea of the elevation of the transept and the nave had already been formed. The interior, despite later modifications or alterations, still displays a very homogeneous design (Figure 6.7). This feature is also emphasised in the Liber Sancti Jacobi: ‘In truth, in this church no fissure or fault is found; it is admirably constructed, grand, spacious, bright, of proper magnitude, harmonious in width, length and height, of admirable and ineffable workmanship, built in two storeys, just like a royal palace.’26

The same Codex, compiled by an unknown cleric after 1140 and finished by 1165,27 provides us with some information regarding the personnel involved in the enterprise: ‘The master stonemasons who first constructed the basilica of the Blessed James were called Master Bernard the Elder, a marvellous master, and Robert, who, with about fifty other stonemasons, worked there actively when the most faithful lord Wicart and the lord canon of the chapter, Segeredo, and the lord abbot Gundesindo were in office, in the reign of Alfonso, King of Spain, and in the episcopacy of Dom Diego I, most valiant knight and generous man.’28

Apart from speculations that Bernard and Robert may have been French, we know absolutely nothing about the two master masons. The name Wicart poses a philological problem.29 But the Prior or treasurer Segered and Abbot Gundesind – the latter was responsible for liturgical duties – are known through other sources.30 Both died before 1111 and 1113 respectively. Bishop Diego is characterised as being a very generous man. This is an explicit reference to patronage, stressing above all the bishop’s financial donations. The king is only mentioned because it happened during his reign, but not as an actual benefactor. All the workers were ministrantibus fidelissimis, which can be rendered as faithful servants [of the lords Segered and Gundesind]. This passage seems to suggest that Segered and Gundesind were a kind of rector fabricae while the bishop only guaranteed the fabric fund. Both were responsible for the building activities in a broader sense. The next paragraph in the Liber Sancti Jacobi states the time of completion previously mentioned. The building was begun in 1078 and completed after 44 years in 1122.31 These dates are a topic of great debate, but the questions are not of interest here.32 The real surprise is rather that there is no mention of Bishop Diego II Gelmírez whatsoever, although he is referred to a few paragraphs earlier as donor of the new silver antependium.33 This is quite peculiar, because the construction period given in the Liber Sancti Jacobi from 1075/78 to 1122 clearly shows that of those years, Gelmírez governed almost 30 years as head of the diocese. Nevertheless, in the Historia Compostellana he is referred to as sapiens architectus acknowledging his rôle as builder.34 One might also inquire why the author or the compiler of the Liber Sancti Jacobi only mentions people responsible for the construction until the end of the first decade of the 12th century.

Bishop Peláez was, as has already been mentioned, deposed in 1088. He was not buried in the church. The seat of the see remained vacant until 1094, when Dalmacio, a former monk of Cluny, was elected bishop of Iria Flavia.35 In his very short episcopacy – Dalmacio died in December 1095 – he achieved two important goals. At the council of Clermont-Ferrand in 1095 he was granted permission by Pope Urban II to transfer the see from Iria Flavia to Santiago de Compostela and to subject the bishopric only to the papacy.36 After the death of Dalmacio, another vacancy of the see of nearly five years followed. In 1100 Diego Gelmírez became the first bishop to be elected bishop of Santiago de Compostela.

Diego Gelmírez was in charge of the see as vicarius during both vacancies until he finally became bishop of Santiago de Compostela.37 In 1120 he achieved a long desired aim: Pope Calixtus II elevated the bishopric of Santiago de Compostela to an archbishopric, as a first step temporarily and four years later permanently.38 This seems to be Gelmírez’s greatest triumph, one he worked towards for almost twenty years, spending a fortune in bribes and risking many conflicts with the cathedral chapter and the citizens of the town. As bishop, Gelmírez was unquestionably a patron in a general sense.39 But his zeal for the church project can be illustrated by four incidents in particular. First, Gelmírez commanded the old sanctuary including the altar of St James be re-designed. This happened shortly after his election as bishop between 1102 and 1105 and – this seems significant – he did this against the resistance of the cathedral chapter.40 Second, he stole important relics during his visit to Braga in 1102 in order to present those relics to the cathedral or to furnish the new altars in the new presbytery with these relics.41 Third, he donated the new antependium for the main altar;42 and finally, around the year 1120, he gave the order to construct a new monastic church for the convent of Antealtares.43 This new monastic church received a new patron. It was now called San Pelayo. Pelagius was the hermit who, according to the legend, saw strange lights which led him to a certain tomb. He informed Bishop Teodemir of Iria Flavia, who recognised the tomb as that of St James.44 With this new church, the monks of Antealtares lost not only their last direct connection to the cathedral but also their traditional rights on the altar and the tomb of St. James. Henceforth the archbishop and the chapter had the full authority over the church, the saint and his cult.

Gelmírez made an effort to win the royal dynasty of Castile-León as patrons of the saint and his church. This was a rather difficult enterprise and an enterprise without a happy end, but at the very beginning the idea seemed quite promising. The husband of the later Queen Urraca, Raymond of Burgundy, was buried in the cathedral in 1107.45 Gelmírez served the count for some years as publicus notarius, scriptor, cancellarius, secretarius et confessor.46 Raymond represents the first member of the royal dynasty to be buried in the cathedral, and his tomb constitutes the beginning of what decades later would be called the Pantheon de los reyes. When Raymond died, the bishop and the count of Traba became guardians of the infant Alfonso Raimundez, the later King Alfonso VII.47 This was the next opportunity to bind the future king to the church of St James. Although Alfonso, on the initiative of Gelmírez, was crowned King of Galicia in 1111 and received the accolade in 1123 – both events took place in the cathedral – the relationship between the bishop and Alfonso remained strained, as did the relationship between Gelmírez and Alfonso’s mother, Queen Urraca.48 The queen, who died in 1126, was buried in San Isidoro in León, the monastery she had favoured with her support. Alfonso, who died in 1157, was buried in the cathedral of Toledo.

From the perspective of the royal family and their political interests, the main reason for their lack of interest in and support for the saint and his church may have been motivated by Santiago de Compostela’s geographical location on the very edge of the realm, or as the Liber Sancti Jacobi called it, finis terrae. Santiago did not represent the heart of the realm, where one could establish a royal residence, a coronation church and a burial place for the memory of the dynasty. Royal patronage at the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela can be observed later, in the second half of the century when King Fernando II paid a lifelong salary to Master Matteo, responsible for rebuilding the western part of the cathedral from 1168 onwards. But this lies beyond the scope of this paper.

Gelmírez was not only the ecclesiastical sovereign over the church and the tomb of St James, but also the secular ruler of the town. While the pilgrims may have supported the building activities by donating money to the altar of Saint James, the citizens had a rather ambivalent relationship to the bishop. We know of two civil uprisings against the bishop and the cathedral. In 1116, Queen Urraca deliberately set parts of the regional nobility, parts of the cathedral chapter, and a part of the citizens against the bishop. The situation escalated, and in 1117 the mob set parts of the cathedral on fire.49 In 1136 the situation was almost the same but with different alliances. But again, the citizens besieged the cathedral.50 We do not know how great the damage was and what portions of the cathedral were affected.

Finally, we must briefly consider the canons of the cathedral chapter. As the Liber Sancti Jacobi proves, there was a kind of magister fabricae who administered the construction work on behalf of the bishop and the chapter. We know from both the Liber Sancti Jacobi and the Historia Compostellana that the treasurer Bernard donated money to build a new water supply and a well in front of the north transept façade for pilgrims.51 We have no information what the administration of the fabric meant regarding the design. What we do know from the Historia Compostellana is that Gelmírez spent far too much money on his political ambitions, thereby angering the cathedral chapter. The canons had to be patient many a time, before getting their new cloister and claustral buildings.52

To make a long story very short, the Romanesque cathedral provides a good example for demonstrating how a wide range of protagonists played different roles when considering patronage in a broader sense. Bishop Diego Peláez and King Alfonso VI launched the project, but Alfonso preferred as burial place the abbey of Sahagún. Ambivalent too was the attitude of Queen Urraca and King Alfonso VII. Both supported Gelmírez as long as it corresponded to their interests, both opposed him when deemed useful. Both decided not to be buried in the church of St James. Gelmírez’s interest in the new church building was rather an interest of convenience. He needed a large church to enhance the significance of the apostle and to accomplish his mission to become archbishop. The chapter supported the building activities only up to that point until they felt their own new buildings – the cloister and the claustral buildings – had been delayed indefinitely. The citizens had an ambivalent attitude, too, but the uprisings were not directed against the cathedral itself or against the apostle. These clashes were targeted against the bishop in his capacity as secular ruler over the town. And it was the latter who was the cause of the citizens’ discontent. But the most interesting question for art historians, the question who exerted what influence on the architectural design, remains entirely speculative.