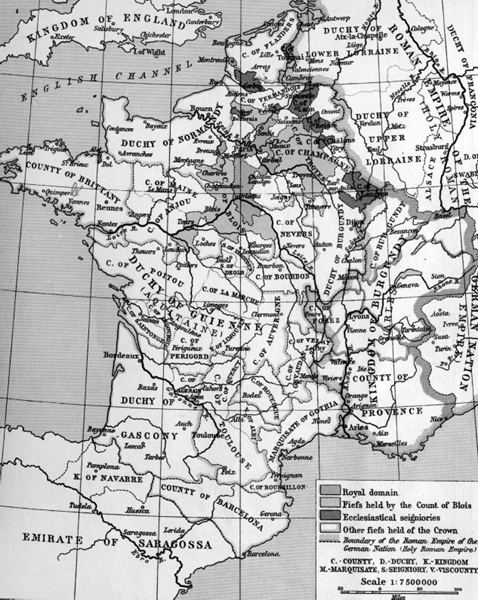

Figure 7.1

France in 1035 (from Shepherd’s Historical Atlas, 1967)

This paper is not so much a contribution to knowledge as a contribution to publicity. The object of the publicity is the March of Gothia, a political unit west of the Rhône on the Mediterranean coast of the Carolingian empire, which continued in existence to the middle of the 11th century and the era of First Romanesque architecture in the area (Figure 7.1). Mentions of it are non-existent or very restricted in prominent architectural studies, such as those of Robert de Lasteyrie, Josep Puig i Cadafalch, Kenneth Conant, Hans Kubach, Éliane Vergnolle and Xavier Barral i Altet.1 What is normally used instead is the Languedoc, or more specifically lower Languedoc, as in the Zodiaque volume of 1978 (Figure 7.2).2 The earliest use of the name Languedoc with reference to a political unit appears to be in the late 11th century, that is after the main period of building in the First Romanesque style.3 I therefore thought it might be worth examining the March, to see if it had any relevance to the buildings and how their patrons saw themselves and their commissions.

The boundaries of the area remained remarkably consistent through centuries of violent change, reflected in a variety of names. Its origins are at least as old as the Roman empire, in the form of the province of Gallia Narbonensis Prima, which extended from the Rhône to the Pyrenees (Figure 7.3). By 476, when the area formed part of the Visigothic domains, it had come to be called Septimania (Figure 7.4). In 507 the Franks pushed the Visigoths out of Gaul, except, that is, for Septimania (Figure 7.5). Next, the Arabs invaded, traversing the Frankish kingdom up to the Loire, including Septimania, between 718 and 732. Between 732 and 740 the Franks pushed the Arabs back across the Pyrenees, except, once again, for Septimania (Figure 7.6), then in the 750s they completed the task and took that territory as well. Its exceptionalism can be partly explained by its geography, as mountains about 60 kms inland separate it from the interior to the north, while the Pyrenees are more traversable at the coast than further west. In the late 8th century, under Charlemagne, Septimania was made a duchy, no less.4

In the 9th and 10th centuries the Carolingian empire saw the establishing of a number of feudal entities north and south of the Pyrenees, including the counties of Toulouse, Barcelona and Roussillon, and the March of Gothia, the last replacing the Duchy of Septimania (Figure 7.7). The counties of Toulouse and Barcelona have reasonably clear historical outlines. Toulouse was in existence in the early 9th century, a new dynasty was started in 852 with Raymond I, and it became the centre of power in the south-eastern quarter of France until the 13th century. Barcelona was also established in the first half of the 9th century, and began a new sequence of rulers with Wilfred in 873, which ran into the 12th century, taking over the rest of the Spanish March, including Roussillon, after which it become part of the Principality of Catalonia.5

The March of Gothia is less clear. It was probably instituted in the middle of the 9th century, as Bernard of Septimania was executed in 844 and marquis Bernard of Gothia ruled from 865 to 878, while a papal bull of around 904 refers to a monasterium sancti Petri in Gothia. It is spoken of as ending with William I, duke of Aquitaine, in 918, but in a record of a gift to the abbey of Saint-Gilles in 961 the donor, Raymond, is called marquis of Gothia, it is referred to in the time of William Taillefer, who died in 1037, and Hugh, count of Rouergue, who died around 1054, was also known as the marquis of Gothia. Thereafter nothing is recorded as taking its place until the advent of Languedoc in the late 11th century.6

It has been suggested that Gothia was so named because of the high proportion of people of Visigothic descent living there. It might seem odd for the Carolingians, themselves Franks, to adopt, or allow to be adopted, the name of their erstwhile enemies, especially in preference to the existing, and Roman, name of Septimania. The answer to that might be that the Visigoths were not only no longer the enemy, those living in the Iberian peninsula under Arab rule were now allies, and seen as part of the Reconquista. Such an attitude would also explain the defining of Gothia as a march, one related to the Marca Hispanica as the Frankish frontier with the Arabs, with a corresponding status.

Turning to the architecture, very little is known of the area in the 9th and 10th centuries, though an Iberian character is indicated by the use of the horseshoe arch in the church of Saint-Martin-des-Puits of that date. It can be compared with churches in the peninsula such as those at Quintanilla de las Viñas and Baños de Cerrato, a type of building previously considered Visigothic but now dated on good grounds to the period of Arab rule in the 8th and 9th centuries.7

First Romanesque buildings in Gothia are clearly related to the First Romanesque buildings of Lombardy, where the style was formed. By what route was it introduced? The most direct is overland via Provence to Gothia and then to Catalonia (Figure 7.1). That is what appears to have happened in the regions to the north of Lombardy, towards Lake Geneva: people building interesting new buildings and neighbouring patrons then noting and emulating them. The same could have applied to Provence, through buildings such as the churches at Valdeblore, Levens, Saint-Pons and Sarrians, which have been tentatively dated to the first half of the 11th century.8

The alternative route is via Catalonia. This was Marcel Durliat’s view, and there are good reasons for agreeing with him.9 Three of these stand out. The first is the opening up of the sea route from northern Italy to Provence, Gothia and Catalonia in the 10th century. In the words of Christopher Hohler, ‘If any single event can be thought to have touched off the economic revival of the 11th century it would seem to be the capture and holding to ransom of Maïeul, abbot of Cluny, by Saracen marauders in the summer of 972. He was returning to Burgundy from Rome, and his captors came from a pirate settlement near Fréjus which had successfully resisted all attempts to dislodge it for nearly a hundred years. St Maïeul’s ransom was duly paid and he was released. But Cluny was the head of an influential congregation of monasteries, and they had been hurt in their pockets. A military coalition was at once assembled which, without delay or apparent difficulty, drove the Saracens at last and forever from the Riviera.’10

The second point supporting the sequence Lombardy, Catalonia, Gothia is the number of buildings in the style of the first third of the 11th century in Catalonia (earlier and more securely dated than equivalents in Provence), and the striking design of some of them.

The third is the character of the First Romanesque buildings in Gothia. These can be represented by three major monuments, namely the churches of the monasteries of Lagrasse, Quarante and Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, datable to the second and third quarters of the 11th century (Figure 7.8).11

At Lagrasse the south arm of the transept with its three apses survives, the central one larger than the other two, while the vestiges of the north arm allow it to be reconstructed with the same form (Figure 7.9). The remains are undated.12 The plan is very like the equivalent parts of Santa Maria at Ripoll in Catalonia of 1020 to 1032 (Figure 7.10), which has three apses on each arm of the transept. There are two things which suggest that Ripoll is earlier than Lagrasse. The first is that its plan can be directly related to that of its model, St Peter’s in Rome (Figure 7.11), in having six units on the wall of the transept, and, as the apses at Ripoll are all the same size, the larger central apse in the set of three on the south arm at Lagrasse looks like a development out of Ripoll.13 Second, the more finely cut masonry at Lagrasse also suggests a later date.14 Neither of these observations constitutes proof, but they both support the same conclusion.

Quarante was consecrated in 1053 (Figures 7.12 and 7.13). It has a barrel-vaulted nave, east arm and transept arms, domes on squinches over the crossing and the south bay of the south transept and groins in the aisles. On the exterior, the main apse has eaves niches and the south apse paired arched corbel tables. These features make it very like Sant Vicenç at Cardona, which was built between 1019 and 1040 (Figures 7.14 and 7.15).15 It is of course possible that the consecration of Quarante took place long after its construction, but accepting the evidence at face value again places the marcher building at a later date than the Catalan one.

Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert is more complicated as it contains the remains of three builds all broadly datable within the 11th century: the earliest church, of which two bays remain at the west end of the nave, then the main bays of the nave with a restricted transept and east end, and a later east end (Figures 7.16 and 7.17).16 There was a consecration in 1076. This has been related to each of the three periods of construction, but the majority view now has the nave belonging to the church consecrated in 1076 and the new east end built in the late 11th century. The aisled nave, restricted transept, barrel vaults, squinches and arched corbel tables of this middle build all relate Saint-Guilhem to Quarante, and via Quarante to Cardona, and, if the 1076 consecration date is accepted for this part of the church, then there can be little doubt that it is later than the Catalan building. Thus, all three of these churches are closely related to buildings in Catalonia, and are almost certainly later than them.

Institutional links do not prove or even suggest Catalan primacy, but they indicate the close connections between the two areas. Thus, Lagrasse was in receipt of donations from Catalans. It also had dependent monasteries in Catalonia, including Sant Pere del Burgal, as around 950 Sunyer, abbot of Lagrasse, returned land to the abbess of Burgal. In the middle of the 11th century the archbishop of Narbonne was a Catalan, son of the count of Cerdanya and nephew of Oliba of Ripoll, while the counts of Barcelona had an interest in the monastery of Corbières near Lagrasse.17

If the preceding arguments and observations provide a reasonable case for the derivation of the First Romanesque architecture of Gothia from Catalonia, that immediately raises the question of motive: why should patrons, especially those who were natives of Gothia, wish to identify themselves with Catalonia? Perhaps the key issue is, where did people think they lived? The County of Toulouse, as the de facto centre of power, must be a possibility, but the paucity of architectural links tells against it.18 If the identification was with the idea of Gothia, then the orientation would have been towards the Iberian peninsula, and therefore, most immediately, to Catalonia. An answer might also lie in the associations with the Visigoths. Should patrons have wanted to underline those associations in the sphere of architecture, might they not have selected the building types of the area of the Iberian peninsula most immediately available to them? It can only have helped that the leading structures of the period in Catalonia were among the most noteworthy anywhere in western Europe in the first third of the 11th century (and it has to be acknowledged that that could have been the main reason for emulating them). There could also be a negative possibility, namely that the First Romanesque style was adopted in Gothia in order to distinguish it from whatever was the current manner of the County of Toulouse. If this sounds far-fetched, then it is worth noting Sheila McTighe’s suggestion that Catalonia adopted the First Romanesque style to differentiate itself from its Iberian neighbours to the west.19

In conclusion, I hope I have provided some basis for considering the March of Gothia a possible explanatory tool in the study of the First Romanesque architecture of its area, by reference to its name, the route by which the architectural style was introduced, the character of the buildings and surmises about the attitudes of their patrons.

I would like to record my thanks to the many people who have so generously helped me with this paper, including Euan McCartney Robson for information and arguments, Malcolm Thurlby for the same and photographs, Claude Andrault-Schmitt, Manuel Castiñeiras and Jordi Camps for bibliographical advice, Robert Boak for identifying a hiatus, Sible de Blaauw for his plan of St Peter’s and Chris Kennish for his expert draughtsmanship.