‘We have sent back your workmen,’ the prior of Grandmont supposedly wrote to Henry II some time after the death of Thomas Becket.1 One imagines English masons sailing across the Channel and riding through France in order to build a church in the harsh landscape of the Massif Central, a landscape that possibly evoked in the minds of the English the northern Marches of the Plantagenet Empire on the Anglo-Scottish borders.2 Could there be a better example of direct patronage in the history of architecture? However, a careful reading of the Latin reveals that the traditional translation is incorrect. A fuller and more literal translation should read, ‘We have sent back the workmen that your devotion had assigned to the church building’ (operarios remisimus devotionis vestrae aedificacantes ecclesiam domus tuae Grandimontis).3 Moreover, the letter that contains this sentence, supposedly written by Guillaume de Treignac, is probably a forgery. It is included in the French Patrologia Latina and in the English Materials for the History of Thomas Becket but not in the more exacting Scriptores ordinis grandimontensis published by Jean Becquet.4 Scholars tend to overestimate Henry II’s concern to found new religious houses as the result of Becket’s murder. However, the purpose of this paper is neither to sift the sources, nor to reinterpret the architectural evidence. Instead, my intention is to set what is known of the medieval abbey buildings in the context of contemporary architecture in the region and in France. In the last four decades of the 12th century, a singular ascetic architectural trend developed that persisted in smaller and often much later Grandmontine churches. Whether these buildings should be categorised as Romanesque, however, is a question that exceeds the parameters of this short essay.

Does the argument for Henry II’s direct patronage entirely crumble as a result of a more critical reading of the texts? Not at all. Links between Henry II, his sons, Richard and John, and the priors of Grandmont did exist. At times the relationship was very warm, as can be seen in a letter by Prior Pierre Bernard, which invokes the king’s love and reveals a strong personal friendship:

Praecellentissimo principi D. Henrico Dei gratia Anglorum regi, duci nostro Aquitanico, magnificentissimo pauperum Grandimontensium nutricio… . O si legere posses in corde meo, quod tibi de amore tuo, suo digito Deus inscribere dignatus est! Profecto cognosceres quod nulla lingua, licet erudite, sed nec stilus sufficiat exprimere quae in tabulis cordis carnalibus, Dei Spiritui placuit imprimere. Hanc pro uobis prosequemur obsecrationem in uestro Grandimonte, ab hoc primo electionis nostrae, ut latores praesentium notum facient … 5

Some of the facts and events that marked this friendship are well known. As early as 1159, during Henry’s reign (Henricus, nulli regum pietate secundus),6 several royal chronicles and courtly letters betray a striking appreciation of the Grandmontine brethren. Moreover, Grandmontine priors were trying to help Henry by encouraging Becket’s return to England. According to his first will, the king’s intention was to be buried at Grandmont. And Grandmont also received gifts of moral value, such as the famous Verneuil ordinance concerning debtors.7 Henry stayed at Grandmont on several occasions:8 some months after a consecration of the church in 1167;9 possibly in 1173; again some four years later when he bought the county of La Marche for 6,000 marks; in March 1181 he reached an agreement with the bishop of Limoges at Grandmont; once more in May and June 1182; and possibly for the last time in 1183. Despite its remote location in rocky hills accessible along rough paths, Grandmont was a stage on the pilgrimage road to the Virgin of Rocamadour. The same road leading from Martel to Le Mans (via Grandmont?) and on to Rouen was also taken in June 1183 by the funeral cortège of Henry the Young King, el jove rei englès, whose death was lamented by the Limousin troubadour Bertran de Born as well as William Marshal.10

Above all, Henry II devoted both energy and resources to Grandmont, as is demonstrated by the gift of a piece of the True Cross brought from Jerusalem in 1174, by the grant of a papal bull for Grandmont, and above all by the negotiations he conducted with Pope Clement III to facilitate the canonisation of the Order’s founder, Etienne de Muret.11 The resulting revelatio or elevatio was attended by high ranking archbishops and bishops, and the saint’s virtue manifested itself through healing and the working of miracles. The translation took place on 30 August 1189, two months after the king’s death, as was accurately recorded in the narrative of the ceremony.

Richard I acted in charters for Grandmont as the Count of Poitiers and Duke of Aquitaine before 1189, and afterwards as king, when he is described as Rex Angliae Ordinis Grandimondis Mecenas.12 He probably helped complete the buildings of Grandmont and commissioned some of its greatest opus lemovicense reliquaries. As for King John, it is likely that he paid greater attention to Grandmont than has been generally thought. He was concerned by a crisis among the brethren when he visited the monastery, arriving from La Rochelle in April 1214.13 He created the potential for future English foundations in March 1203 at Rouen, when he declared the Grandmontines free of every toll or service. Significantly, it was the lords of his court – his marcher barons – who founded Grandmont’s three English dependencies. These were Robert de Thurnham and his wife, Joan Fossard, who founded Eskdale- Grosmont in Yorkshire c. 1204; Walter de Lacy, who founded Craswall c. 1225; and Fulk Fitz Warin III, who founded Alberbury (Shropshire) between 1226 and 1234. The latter became an ‘outlawed baron’ after his death, while his funerary foundation in woods on the River Severn serves in what was to become the legend of Robin Hood.14

We can list various other grants from members of the Plantagenet family. Grandmont was supposedly left a large sum in the will of the Empress Matilda. Her son, Henry II, sent seven white bear furs in 1178 – a donation that is confirmed in the Pipe rolls.15 According to Gervase, Henry’s will of 1182 made provisions for 3000 silver marks to be given to Grandmont (Domui et toti ordini grandimontis iii milia marcas argenti), more than to Fontevraud or to the Carthusians, and Grandmont is the only religious establishment in Aquitaine mentioned in the will.16

It is sometimes suggested that Richard made a donation towards the completion of the buildings when he visited the brethren in 1192, though the given date is impossible as he was then on crusade. More likely, he signed confirmations for the donations from Chinon after his return. His nephew Otho sent one thousand cuttlefishes a year from La Rochelle, and John was generous with charters between 1199 and 1214.17 It is noteworthy that successive Plantagenet rulers continued to show generosity towards Grandmont, including Henry III, who was politically active in what remained of the Plantagenet domains in France.

None of the various gifts outlined above can be associated with the construction of Grandmont’s buildings, unless they are clearly identified as such. Nevertheless, all sorts of alms (including food) would have helped the community in undertaking the construction of the monastery.18 Alfonso’s VI annual payments of Spanish gold to Cluny must similarly have helped the Burgundian monks build their new church.

The history of the abbey buildings and their later fate can be briefly summarised, picking out the few facts from the hagiography that has been built around them. The founder, and future saint, Etienne, set up his hermitage at Muret, near the village of Ambazac, where he died c. 1124. Thanks to the lord of Montcocu, his successors established a community of religious nearby, on the higher hills, in a ‘priory’ (Grandmont was not described as an ‘abbey’ until the 14th century). Around twenty years after Etienne’s death, the lawmaker and fourth prior, Etienne de Liciac, composed a rule inspired by that of the regular canons. Misled by numerous later forgeries, some scholars have presumed an early diffusion of Grandmontine houses. However, the spread of the order in France (with more than 150 sites) is most likely to be contemporary with, or even subsequent to, the elevatio of Saint Etienne in 1189. The three English foundations fall exactly into this period, while the two Grandmontine houses in Spain, at Tudela and Estella, were founded later still, after 1265 and 1269, thanks to Thibaud de Champagne, King of Navarre (1253–70).

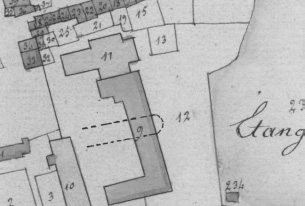

As far as the history of the mother house is concerned, disputes between the monks and the lay brothers troubled the papacy through much of the Middle Ages and began against the background of the Plantagenêt-Capetian wars.19 Contrary to popular perception, this did not presage decline for the institution and, despite internal strife, the monastic buildings increased in size. An early church on the site was destroyed after 1733, when the then abbot decided to construct a shorter and more lavish church ‘in the style of the Paris Pantheon’.20 The new church was constructed to the north of the earlier church, in order to maintain the liturgy in the course of construction, though the subsequent building of a large new wing cut the medieval church in two. The new buildings, together with what remained of the medieval convent and its cemeteries, were destroyed after the Order was dissolved in 1772/1781. A cadastral map gives a good idea of the disposition in 1813 (Figure 9.1), though the belated consequences of the French Revolution destroyed what was left, and even dried up some of the lakes and ponds, in spite of local resistance.

Not all the sources reporting royal grants of lead to Grandmont are reliable. As we have already seen, the Limousin sources are to a large extent legendary. However, grants of lead are mentioned in a small number of charters and English diplomatic or financial records that are trustworthy. In some instances, such as the 1176 gift of lead, the pipe roll evidence confirms what is suggested in the legendary sources, thus supporting the historical veracity of the event. The Great Roll of the Pipe for the Twenty-Second Year of the Reign of King Henry the Second states briefly that a sum of £40 was paid for lead from the Carlisle mine ‘for the house of God at Grandmont’ (Et pro plumbo at opus domus Dei de Grantmonte). Another line records: ‘And for the location of two vessels to transport the lead that the king gives to the church of Grandmont, from Newcastle to La Rochelle’ (Et pro locandis. ij. navibus ad ducendum plumbum quod rex dedit ecclesie de Grosmunt a Novo Castello usque ad Rochell’. xj. l. et. ix. s. et. iiij. d. per breve Regis).21 There is nothing surprising in this donation. The English kings had given lead tiles for church roofs to other institutions on several occasions. For example Henry I gave lead to Chartres and Richard I gave lead to Pontigny. Above all, between 1178 and 1188, Henry II arranged for lead for Clairvaux, to be transported initially from Newcastle to Rouen. It is important to note that in the gifts to Clairvaux a precise number of carreatis plumbi or caretatas plumbi is quoted (‘a cart’ should be understood as a ‘cart load’ and defines a measuring unit rather than referring to a type of vehicle).22 Sometimes these cart loads waiting in the harbours had to be guarded, thus greatly increasing the cost. It would obviously be helpful to find precise references concerning the cost of lead sent to Grandmont, but there are none in the Pipe Rolls. This does not necessarily mean that there were no other donations. The lead for the roof of the cathedral at Le Mans, for example, is not included in the accounts, and similar gifts are very difficult to detect in Richard’s time.23 Besides, according to the Pipe Rolls, the Carlisle mines provided only three gifts of lead for continental buildings in Henry’s time: Caen in 1169, Grandmont in 1175/6 and Clairvaux between 1178 and 1188. Moreover, among the three, the grant to Clairvaux was not strictly a gift but an exchange, because in return, and revealing a background in anti-heretical and diplomatic operations, the abbot sent to the king one of St Bernard’s fingers.24

The history of the donations of lead left a strange legacy in Grandmontine and Limousin narratives. Jean Roudet, a 17th-century monk from Le Breuil-Bellay in Anjou, wrote a now-lost chronicle that mentioned an epic journey transporting a lot of carts of lead from La Rochelle. This was then inflated to 800 in some later copies. The arithmetic certainly suggests 60 cart loads for Grandmont could be more or less accurate.25 Roudet’s copiers went even further in developing the legend of the Grandmont lead. Each of the so called ‘carts’ was said to be driven by eight English horses, all of the same hair and colour. They were attended by the king’s officers, who, amazingly, had decided that they were not rich enough to donate their own money, and left the abbey to the charity of the Plantagenet kings. The same secondary sources also suggest a failure of ambition to complete the building, and that the kings were persuaded to limit their largesse. Perhaps it was the modesty of the church that meant that no 17th-century commentator wanted to associate it with the patronage of princes.

Beyond this fairy tale, it is worth considering seriously the name given to the supposed driver of the lead carts and ‘English horses’ – a man called Brandin. Brandin is a historical figure. He was a mercenary who later became King John’s seneschal in Gascony. Clearly, there is a confusion between the period in which the story is set, and the part played by the seneschals to Otho, Richard, Eleanor and John, who were either warriors from low extraction, like Pierre Bertin, or English knights.26 None of them were active in 1175/6. They were still infants in the 1170s, but above all, they had no early interest in Grandmont because the county of La Marche had not yet been purchased by the Plantagenets. The keys to this historical confusion are the carved coats of arms, inscriptions and iron seals that were found at Grandmont, referring to Brandin as well as to magnates who were loyal to Richard but then made peace with John. These included Robert de Thurnham († 1211), seneschal of Anjou (1194–99); Poitou (1201) and Gascony (1207); and the Anglo-Irish (and Anglo-Welsh) Walter of Lacy, who was recalled from Ireland, landed at La Rochelle and then rode to Grandmont with King John on February 1214 (he was to be one of John’s executors two years later).27 These men were commemorated at Grandmont because of their gifts to the abbey.28 In contrast to the monks’ local aristocratic friends, Hugh Brun de Lusignan, who became count of La Marche after his enemies, the Plantagenet kings, had been deprived of their lands in northern Aquitaine, was commemorated but not buried at Grandmont. Grandmont served as a memorial and spiritual centre for the rulers of La Marche, from Henry II through to the later Lusignan counts, but none of them were buried there.

Whatever the truth may be, three points stand out. First, the lead roof is a recurrent feature in all descriptions of Grandmont. It was partially robbed in 1597, during the neglect that followed the Wars of Religion, then repaired, and replaced in 1702.29 The old tiles were saved, however, and reused over the new church in the 18th century. The original lead roof could have been a source of local pride, shining bright among the dark hills, comparable to the effect of the roof of Saint-Martial in Limoges. Second, we should seriously consider the possibility that Henry II and Richard provided financial support for the construction of the monastic buildings, as well as for the church and its lead roofs. These monastic buildings included an enclosure wall with towers, an infirmary, a rectangular vaulted cloister with lead pipes and a lead pond, a chapter house and a refectory. This last is a reminder that the king liked ‘to partake the brothers’ meals in the refectory’.30 We must also imagine at least two ‘houses’ for the English kings near the main door, perhaps connected to a double chapel – which explains the name l’Angleterre given to the northern terrace, regarded as an ‘English land’. Third, it is clear that the period between c. 1190 and c. 1215 was as important for the institution as the reign of Henry II.

In October 1166 seven bishops led by the Archbishop of Bourges dedicated a church to the Virgin Mary at Grandmont, in which they placed relics of St Martial that had been borrowed from Limoges. Apart from the Archbishop of Bourges, the Norman Froger de Sées, a man close to King Henry II, was present, as well as the rival archbishop of Bordeaux, all the bishops of Aquitaine and several counts and knights. The translation of the founder’s corpse was also celebrated, either several days earlier, or a few months later – the sources are unclear. The gift of lead was made ten years after this consecration as a contribution towards the construction – comparable with the seven years that elapsed between the consecration of Clairvaux (1174) and the reception of the first cart loads of lead there.

We also know the names of two masters of works. The first is described as magistrum operis Gerald, who was assisted by caementari et alii operarri in the time of Stephen de Liciac, that is to say before 1163. A legend connected with this Gerald informs us that after a terrible fall from the top of an arch, he recovered as the result of the intervention of the saint: non est mortuus iste operarius sed dormit.31 Another name appears in the obituary: Johannes Gastineus ecclesie nostre edificatory.32 This Jean Gâtine, whose name is French, died before 1170, when the obituary was written. He is probably the builder of the main part of the church, as it was consecrated in 1166.33 The masonry work, especially the nave, is sometimes assigned to the lay brothers rather than to secular builders. Although the contribution of the lay brothers to monastic building work has become a commonplace, it was real enough at Grandmont, where the whole institution was sustained by the economic and political power of the lay brethren. The lay brothers’ choir was situated in the western part of the nave.

The church was incomplete at the time of its consecration. Just before 1170, the prior, Pierre Bernard, is said to have vaulted the whole refectory, and to have finished the church from the chevet to the entrance of the brothers’ choir. The church had been begun at the low (western) end.34 In view of the sources, the dating of the church to c. 1160–75 seems reasonable, but does this date correspond to what can be adduced of the church in its late medieval state? The presbytery seems to have received attention after the primary build. In 1190, the Count of Champagne gave a rent for candles, later confirmed by Thibaud IV and Thibaud V. The setting of the reliquaries on the seven steps of the high altar is described in the treasury inventories and has been debated by J.R. Gaborit and G. Souchal.35 After receiving a fragment of the True Cross, some relics of the Virgins of Cologne arrived in 1181 – the result of a celebrated journey by four Grandmontine brothers to Germany.36 The main reliquaries were probably intended for the elevatio of the Saint in 1189, a few years after the treasury was robbed by Henry the Young King in order to pay his mercenaries. But the dating of the reliquaries is complicated: the enamels were clearly ordered at different periods. A dating to about 1189 or a few years later is generally accepted for the surviving big shrine, known as ‘the Ambazac shrine’ (Figure 9.2), although this contained a relic given in 1269 by Thibaud de Champagne. The apostles of the surviving antependium are dated c. 1230–40.37 It is worth noting that the Grandmontines were famous for their enamel reliquaries, antependia or altarpieces. They survive from both the mother house and a number of smaller houses. Indeed, the most beautiful ‘champlevé’ enamel I know comes from Cherves near Cognac and is now in the Metropolitan Museum at New York. These objects deserve to be mentioned in the context of a discussion of the architecture for three reasons. First, because of the deliberate contrast they promote with an austere building. Second, because their disposition clearly cannot date from 1166. This suggests a subsequent reorganisation of the interior, and points to a continuity between Henry II and his successors as patrons of the abbey. Third, because the evidence suggests a liturgical setting that deployed metalwork on a huge scale. It is possible that this interior reorganisation was recognised in a new consecration in 1219 by the Archbishop of Bourges, although this consecration has been linked to a supposed renovation after the church had been damaged by excommunicated men.38

Interpretation of the descriptive sources is marred by the contradictions and uncertainties surrounding the measurements, and by the terms used. Was a ‘jambée’ a leg, for instance? The first account was written by Pardoux de La Garde before 1591,39 and a second by Jean Levesque in 1662.40 A cost estimate from the 18th-century builder, Naurissart, is also very useful.41 All three sources describe an aisleless church that was tall, very narrow and very long.42 Two lateral chapels abutted this. A large and beautiful chapel on the north side was dedicated to St Peter and was later used as a sacristy. A smaller chapel to the south (the cloister side) was dedicated to St John the Baptist and St Bartholemew but also to the founder, because it was supposed to be on the site of the first humble church, and it sheltered the graves of the early priors, including Etienne. It was here in 1738, while digging the foundations for a new kitchen, that the tomb of Guillaume de Treignac was discovered. One author describes a northern chapel (which may be the same or another) belonging to the ‘English cemetery’, which was dedicated to St John the Baptist. He describes it as a double chapel, ‘a vault upon a vault’, with the upper chapel dedicated to St Michel.43

The church had twenty-two windows, probably eight for each wall of the nave. They must have been deeply splayed given the thickness of the lateral walls. But there were no bay divisions, properly speaking, because the transverse arches of the masonry vault sprang from corbels, or from projecting courses of ashlar – a point which surprised Pardoux when he saw a fallen stone of the vault, ‘the size of a goose heart’. More amazement was produced by ‘odd piers’, used as liturgical markers (to borrow a term used by Eric Fernie):44

Cette église est belle par excellence pour la longueur qu’elle a. Et la voûte d’icelle n’est supportée d’aucuns piliers comme sont autres églises, fors de quatre piliers ou colonnes qui sont fort beaux et excellents qui sont aux quatre angles du grand autel joignant le premier degré d’icelle. Ces quatre piliers sont fort somptueux et admirables, faits en façon de colonne dorique alias ioniques et la façon d’iceux se nomme en latin stria, strae, ce sont comme gouttières engravées le long des colonnes de pierre ou chanfrein creux qu’on dit communément piliers cannelés lesquels soutiennent la voûte sur ledit autel.

(Pardoux de La Garde, with later manuscript rectifications)

Thus, the high altar was surrounded by four fluted columns with what resembled vertical channels or hollow chamfers. According to the description, the altar was crowned by a ribbed canopy, consisting of eight arches, thirty-two arch sections and golden medallions with flowers (‘platines de cuivre doré’) – a kind of fan vaulting! We do not know, however, whether this was a vault made of ashlar and covered by ribs with liernes and tiercerons, or whether it was a canopy made of painted metal and wood serving as a ciborium. It may even have been a very late addition to the church.45 I was once tempted to interpret the source as evidence for the original architectural disposition, and speculated that the ribs may have been formed by a fully-fledged rib vault – along the lines of the presbytery of the chapel of St-Julien at Petit-Quevilly, created by Henry II at Rouen. However, I suspect the altar complex as described by Pardoux was a late alteration. It could have been a metal ciborium, set upon four columns made of brass and enamel, similar to that commissioned by the bishop of Limoges from a local goldsmith between 1331 and 1333 for the collegiate church of La Chapelle-Taillefert.46 It is important to note that there was in Pardoux’s times a white linen canopy attached to the beautiful ‘vault’ by a metal chain, and that after Pardoux’s time the apse was possibly reinforced and rebuilt (Naurissart saw brick vaults upon pillars and between stone ribs).

Be that as it may, some space was necessary for the daily mass at prime at the high altar, and although the church was wide enough, no description contains evidence of lateral bays, aisles or passageways leading into the apse, or of something that could be interpreted as lateral vaults. The reconstruction of the altar area is complicated by two questions concerning the entire church. First, the vault of the nave is sometimes said to have been a rib vault, but this interpretation is based on a misunderstanding of the word ‘ogive’ or ‘ogif’, which from the 13th to 19th centuries was used to designate a pointed arch (or its stones). Second, in order to understand the altar area, the reconstruction of the whole eastern apse needs to be considered. We know that the apse had five stained-glass windows, given by Hugh le Brun de Lusignan in 1208, just before his departure on crusade, ten years before the re-consecration.47 They represented prophets and apostles, with a date, coats of arms and a dedication: HUGO COMES MARCHIE. HANC FENESTRA VITREAM DEDIT BEATE MARIE. This donation dates the stained glass windows, along with the (rebuilt?) apse walls. Consequently, we can reconstruct a chevet built on a semi-circular or a pentagonal plan – the latter remaining a possibility after the recent archaeological investigations.

Between 2013 and 2018, and for the first time, a programme of excavation was conducted under the direction of Philippe Racinet.48 This is ongoing, but has already revealed an unexpectedly complex number of ground levels, a slope to the underlying granite bedrock and huge stone terraces built to support the later precinct.

As far as the church is concerned, the construction of the 18th-century buildings on the site of the former church is unfortunate, especially as they include a cellar that created a trench separating the apse from the nave. The southern wall of the nave has been completely destroyed. A solid stone buttress occupies the southern part of the apse, built as a reinforcement some decades before the 18th-century excavations (Figure 9.3). Moreover, the masonry includes reused mouldings (from shafts, ribs, cornices, bases, imposts, window embrasures and jambs) that seem to belong to the period c. 1190–1220. These mouldings could come from a monastic building that was demolished early, or from the cloister, and therefore may not have belonged to the first church. Indeed, several isolated capitals of the same period have been found that are too small to have been used in the church, and must have come from elsewhere (Figures 9.4 and 9.5). But, at the very least, these elements point to large-scale work to either side of 1200. Late medieval material has also been uncovered, which could be the work of Guillaume de Fumel (1437–71), or might be from a restoration of around 1475? We know that shortly after this a beautiful tapestry and precious objects were given to the church. The main discovery for the Middle Ages is a tomb of a prelate in a privileged position, carved in the rock in the middle of the church.49

All that remains are the masonry courses of the lateral northern wall and the residue of a semicircular apse. The foundations are of very different depths, from east to west, and from north to south. In the nave, the early levels have all been dismantled but it seems that the pavement level was not very far above the natural substrate. The remains attest to the narrowness of the church (8.20 m intra muros) and the strength of the masonry (between 1.84 and 2.88 m thick), two features that are underlined in all the texts. They also prove that the apse was wider than the nave, as in all the smaller Grandmontine houses. Having found the remains of a wall in a house, archaeologists have also developed a hypothesis about the length of the church, which may have had an external length of 67.40 m (Figure 9.6). It is also likely that the church described by Pardoux, Levesque and Naurissard, preserved the same general perimeter as the 12th-13th-century church.

Three important questions remain for which there is currently no answer. First, the vaulting system in the eastern part of the church remains uncertain, and with it the nature of the presbytery (see above). Second, we are unsure as to the exact design of the chevet, partly because of later reconstruction, but also because it is possible to build pentagonal walls above semicircular foundations. Third, the shape and positioning of the lateral chapels remains uncertain. The northern structures that were discovered may correspond not to a lateral chapel, but to the strong buttress added c. 1643 (which may have been contemporary with the destruction of the chapels).

Whatever the details of the excavation teach us, conjectures as to a specifically ‘Plantagenet’ patronal influence on the design are clearly pointless.50 However, it is possible to discern a distinctive aesthetic at work, evident in the use of crocket and water-leaf capitals and in the narrow aisleless nave – built without vertical wall articulation but seemingly barrel-vaulted and with high-level corbels.

Notre-Dame at Grandmont is best understood as a building which reflects both a local and an international interest in ascetic expression, giving rise to an extremely distinctive plan, here described as ‘arrow-type’. One source for the design may have been the historicist aisleless ground-plans that were used in churches related to the 11th-century Reform, as has been argued by Jill Franklin.51 However, in Aquitaine, there were virtually no examples of long narrow naves before the middle of the 12th century. Therefore, it would be more profitable to look for comparisons among churches that were constructed by other ascetic orders within the larger region of western France, as and when their income enabled them to build stone churches. If the aisleless plan of Grandmont seems strange, it is only because we are used to the type of plan favoured by the Cistercians in Burgundy from the middle third of the 12th century, where the aisles served as a series of chapels. There are Cistercian churches that were originally aisleless, though these are, in fact, too early for my purpose. On the other hand, the female abbeys that were built with narrow and long naves are too late (Les Rosiers, Coyroux d’Obazine). Closer in date and more relevant are early Carthusian churches. Only a few are known, including what was possibly a lay church or ‘correrie’ at Witham (Somerset), and the main church and ‘corroirie’ at Le Liget, near Loches.52 Both foundations were initiated by Henry II c. 1178, and under Hugh of Avallon the community at Witham became important to the king. A long narrow nave is also known to have existed at Boschaud, a domically-vaulted Cistercian church which was a daughter-house of the Poitevin abbey of Les Châtelliers.53

Light can also be shed on the architectural model behind the church at Grandmont by looking at examples in the diocese of Limoges itself (Figure 9.7). The Benedictine church of Saint-Augustin in Limoges, the burial church of the bishops, was built between 1171 and 1180 and had a tall, barrel-vaulted, aisleless nave.54 Above all, Grandmont is not far from L’Artige (near Saint-Léonard-de-Noblat), the mother house of a highly original ascetic order, founded by two penitent Venetian knights, Mark and his nephew Sebastian, both of whom are mentioned in the Grandmont obituary.55 The house was established in a wild and uninhabited spot between 1174 and 1177. The date at which the priory is first described as ‘L’Artige Neuve’ is 1198, and is also the date of the dedication of the church and its main altar, some six decades before a new altar was installed in the presbytery.56 The late-12th century-date is also confirmed by dendrochronology.57 This, however, does not apply to the present church, which was heavily reconstructed (like Grandmont), but it does apply to the cloister. This has short and stocky columns, spur-bases, water-leaf or crocket capitals, and broad pointed arches with roll mouldings. Moreover, the remains of rib-vaults survive from the former chapter house (Figure 9.8). The first church is now best known thanks to excavations, with a short semicircular apse and thick walls – a design that compares closely to Grandmont’s ‘arrow plan’.58 Two lateral chapels, originally barrel-vaulted like the nave, were virtually enclosed and included tombs (Figure 9.9). The north wall of the nave sustained a long gallery, which again sustained tombs, while he northern chapel still preserves its floor tiles. The southern chapel, a parte claustri, was dedicated to St Laurent, and was used for burial of the early priors and the commemoration of the founders.59 As at Grandmont, the presbytery steps were reserved for the graves of high ranking brethren, often former bishops, who probably paid for this prestigious spot.60 Thus, it is clear that different spaces were used for different types of burials. The chapels, where important saints were venerated, were reserved for the pious leaders of the community. High-ranking sinners, on the other hand, reliant on intercessionary prayer, were buried in the middle of the choir.

Grandmont lies between two Cistercian abbeys (there were eleven Cistercian monasteries in the diocese of Limoges), both belonging to the Dalon group and given to Pontigny in 1162. The abbey church of Beuil (Haute-Vienne) has entirely disappeared, but scholars suspect it was a simple single vessel with a large apse. The abbey church of Bonlieu (Creuse) is more interesting.61 The east end might belong to a restoration campaign with groin (or rib) vaults, a pentagonal design and windows surrounded with high oculi. But the major part of the church, built between 1160 and 1180, had a transept and a long aisleless nave (Figure 9.10), once more of the ‘arrow-type’, with the same width as at Grandmont or L’Artige. The remaining bays of the nave (Figure 9.11) were covered by a barrel vault with transverse arches springing directly from the wall, and a series of curious putlog holes left over from the centering of the barrel vault.

The location of the first occurrence of the aisleless or arrow-type church is unknown – Bonlieu, Grandmont, even L’Artige or Beuil. The question is unanswerable in the current state of research. It seems that faced with the constructions of the Burgundian Cistercians, an effort was made in the Limousin to create an alternative architectural image of asceticism at the time of Henry II. The lack of aisles can perhaps be explained by the fact that, as in female orders, nobody was supposed to walk around the liturgical choir. The narrow vessel could perfectly well accommodate the furnishings necessary for a choir. At Le Pin (near Poitiers), a Cistercian church with an aisleless nave that was built two or three decades before the community famously received grants from Richard I, a 17th -century witness saw ‘stone seats’ against the walls.62 At Grandmont we know that there were two long choirs in the nave, together containing at least one hundred seats, one for the monks (with notable burial places in the middle) and a larger one for the lay brothers. L’Artige or Bonlieu have no connection with the English kings. Nonetheless, they may echo Grandmont, or perhaps it would be more accurate to state that all three are evidence of a similar artistic and liturgical programme.

The expression ‘Grandmontine-type’ is generally used to describe smaller daughter houses, and not Grandmont itself. Although the notion of a ‘plan-type’ is anachronistic in relation to these houses, it is remarkable that – far more than is the case with Cistercian churches – all the lesser Grandmontine churches look alike, from Craswall in England to Languedoc, or from Normandy to Burgundy. They are defined by an aisleless and unarticulated nave, invariably barrel-vaulted, no transepts, and a semicircular or pentagonal chevet which is wider than the nave. The churches are small, but built of high quality masonry, as can be seen at Comberoumal near Millau, the best preserved and longest of them at 24 m (Figures 9.12 and 9.13). Some scholars have proposed that the explanation lies in canon 58 of the Order’s Institutio. This specifies:

Quoniam omnis superfluitas a nostra religione prorsus debet esse aliena, ecclesia et cetera nostrae religionis aedificia plana sint et omni careant superfluitate. Omnis pictura et omnis sculptura inutilis et superflua a nostris penitus absit aedificiis. Voutae quidem ecclesiarum sint tantum planae et simplicitati nostrae religionis congruae. Cum enim, testante ipsa Veritate, de omni uerbo otioso reddituri sumus rationem in die iudicii, multo magis de superfluis operibus.63

This badly written and redundant text is followed by a paraphrase from Matthew, 12, 36, saying that the men will be judged as much by their pointless words as by their useless works. The text is neither precise nor original enough to constitute a norm for building. The association between the French ‘vouta’ (a neologism) and the Latine ‘plana’ is also strange. The two words were obviously a description of the barrel vault covering the main space, even if some Grandmontine apses have ribs and liernes (Figure 9.14). The text selects a single feature, and suggests this suffices to constitute the imitation of a model. By this manner, it is possible that the builders of the church of Alberbury (Shropshire) believed that they were also imitating the mother church, although they chose an unvaulted square-ended nave, because they added a beautiful lateral chapel dedicated to St Stephen.64

The architecture of the smaller houses generally belongs to the late-12th-century or to the early-13th- century. Their churches are badly dated or dated very late, as we can see in western France: Breuil-Bellay (Maine-et-Loire) was consecrated in 1211, possibly two years after its foundation; Chassay-Grandmont (Vendée) is dated by dendrochronology to c. 1217/7; Bois-Rahier near Tours, a foundation of Henry II, was consecrated in 1254. I would suggest that the similarities among the buildings are because they all looked to Notre-Dame at Grandmont, even if we do not know how a medieval builder brother would see or imagine the mother house. This said, however, they represent loose adaptations rather than copies.

Patrons play only a very small part in architectural matters. Whoever is the patron, whoever the masters of works, and wherever they originate, an architectural design is always an alchemy, a mixing of international trends, local trends, local know-how and the special requirements of the building’s specification. This is why, contrary to most opinion, Notre-Dame at Grandmont cannot be considered a one-off. All we can say is that Henry, Richard and John, with the consent of their administrators, supported several ascetic movements, and that these in turn promoted and were nourished by one of the great architectural trends of the 12th century. This movement lies behind architectural invention at Grandmont as it does with the architecture of the Carthusians or Templars. But without these three or four English kings, it is arguable that Grandmontine architecture would not exist. That is a lot for which to be remembered.

I am grateful to Philippe Racinet for his science and generosity in sharing with me the first results of his excavations, and to Julien Denis and the archaeologists from EVEHA (Limoges). Many thanks also to Alexandra Gajewski for her expert reading of this text.