Over the last decade, knowledge of female artistic patronage during the Middle Ages has expanded significantly.1 The Kingdom of Aragon, however, has been studied far less than other Romanesque milieux in the Iberian Peninsula.2 For 11th-century Aragonese queens only limited documentary material survives, and the attention given to their artistic undertakings generally has been neglected in favour of that of their husbands, whose patronage is better documented.3 One of the less-studied cases of Aragonese female patronage concerns the so-called Jaca ivories, which were commissioned by Queen Felicia of Roucy around 1100 (Figures 15.1 and 15.2). There is little scholarly consensus on many issues of broad importance regarding their manufacture, including the identity of their patron, their date, their function and the identification of the hands that were responsible for them. In this essay I will argue that the ivories created for the Jaca panels (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Accession no: 17.190.134; 17.190.33) may have been conceived as mementos. Alternatively, and just as intriguingly, the panels may have been made to resemble reliquaries in the manner of contemporary examples.

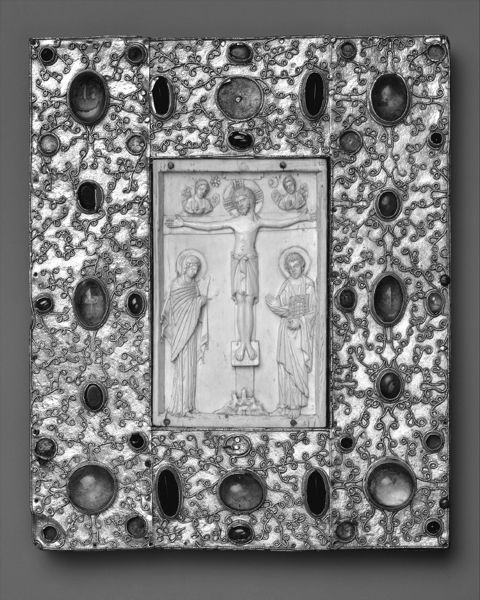

The two Jaca panels consist of wood supports, one displaying Byzantine and the other Romanesque ivory carvings, each surrounded by a precious metalwork frame. Their opulent decoration suggests they were conceived as a kind of liturgical ornamentum. In my opinion, on the basis of technical and stylistic arguments, the setting of the plaques may be attributed to the goldsmiths’ workshop that, under Abbot Bégon III of Conques (r. 1087–1107), fashioned reliquaries out of diverse fragments of pseudo-filigree around 1100. The Byzantine ivory, which depicts the Crucifixion, originally formed the centre of a three-panelled icon dating from the late 10th century.4 M. Cortés suggested a general stylistic affiliation with the elongated forms typical of 10th-century Byzantine carving, which are to be found in ivories such as The Borradaile Triptych (The British Museum, M&ME 1923 12–15,1) and the triptych from the Département des Monnaies, Médailles et Antiques of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Inv. 55 no. 301). However, far from displaying the common features of ivory icons connected to imperial workshops in Constantinople, this ivory seems to belong to an alternate type, more linked instead to intimate and private devotion. From my point of view, morphologically the ethereal and less naturalistic forms of the proposed models appear to be at odds with the simplicity of the folds, the swollen faces, the fleshy lips and the sensuous appearance of the figures in the Jaca ivory, which bear a greater resemblance to two Constantinopolitan ivory plaques depicting the Crucifixion and the Mission of the Apostles from the Museé du Louvre (second half of the 10th century) (Museé du Louvre, Département des Objets d’Art, MRR 354, 422).5 It is most likely that the Romanesque ivory figures were carved purposely following the aesthetic trends of the artistic environment in which the Byzantine ivory was received: the nunnery of Santa María in Santa Cruz de la Serós (Jaca, Aragon).6

These Romanesque ivory figures are framed by repoussé silver epigraphs: ih(e)c(us) || na | zar || en(u)s [Iēsus Nazarēnus or ‘Jesus the Nazarene’] (on top), feli || cia | reg || ina [Felicia Regina ‘Queen Felicia’] (in the lower section), the latter providing the identity of the patron (Figure 15.3). Felicia (1063–1100?) was the daughter of the Count of Roucy (Picardy) and the second wife of King Sancho Ramírez, who ruled Aragon between 1063 and 1094.7 His reign was defined by his determination to maintain the territorial integrity of the nascent kingdom of Aragon and he made several attempts to expand its boundaries. Sancho’s association with the Holy See through the adoption of the Roman liturgy in 1071 and the acknowledgement of his status as a papal vassal eighteen years later fulfilled some of these high aspirations.8 The king also encouraged French warriors to join Iberian Christian forces for the conquest of nearby Muslim-held lands, especially in the so-called siege of the city of Barbastro in 1063–64, which was sanctioned by Pope Alexander II. His marriage with Felicia assured the lasting nature of political and familial bonds, especially with Felicia’s father Hildouin IV of Ramerupt, who had mediated in the relationship between the French King Philippe I and the Papacy,9but also with her brother Ebles of Roucy. Ebles in 1073 led the campaign to liberate the Aragonese city of Graus, which was endorsed by the same Pope Alexander,10 and in 1084 defended Pope Gregory VII, alongside the Norman Robert Guiscard, during his military confrontation with Emperor Henry IV.11 In this respect it is worth noting that the new queen and her siblings descended, on their mother’s side, from the Carolingian kings of the Franks, the early Capetian kings, and the first Saxon king Henry I; they were therefore also distant relatives of Otto I, the great emperor of the Holy Roman Empire.12 Likewise, by the mid 11th century, Hildouin IV of Ramerupt and Alice Adèle of Roucy, Felicia’s parents, increased their power over northern France through the strategic marriages of their children. On the one hand, the marriage of their daughter Beatrice with Geoffrey II, count of Perche, afforded them important political profit and inheritances.13 On the other, the wedding between Ebles, their heir, and Sybille of Hauteville, the daughter of the Norman ruler Robert Guiscard, secured the strong alliance between Rome and the House of Roucy.14 Therefore, Felicia’s family legacy made her a perfect choice of wife for King Sancho, and she helped his governmental ambitions flourish.

The intriguing complexity of the plaques’ arrangement should be understood in light of the queen’s familial and cultural heritage. The circumstances of the reception of the Byzantine ivory possibly can be traced to the constant traffic of portable goods and gifts that played out through commercial and diplomatic networks.15 Indeed, the practice of dismantling Byzantine ivory triptychs for their inclusion on liturgical objects is well attested beginning in the Carolingian and Ottonian periods. The circulation of these precious gifts to northern European lay and ecclesiastical rulers remained a custom well into the 11th and 12th centuries, as illustrated by the covers of the so-called Small Bernward Gospel (Dom-Museum Hildesheim, DS 13) and the Precious Gospels of Bernward of Hildesheim (Dom-Museum Hildesheim, DS 18). Moreover, the close relationship between the Roucy family and the Norman Sicilian dukedom may have been a potential path for the panel’s acquisition and its later transmission to the queen. Thus, it is highly likely that the reception of the Byzantine ivory triggered Felicia’s desire to commission the carving of the Romanesque ivories in order to create a more complex type of liturgical furnishing with them. It is plausible to argue that Felicia, sensitive to the artistic tastes of her own kingdom, was keen to ask an artist from Jaca familiar with the carving methods of Santa Cruz de la Serós to create these ivories.

These small figures featuring a Crucifixion, however, became part of a more significant creative process. In fact, one of the most striking peculiarities of the Romanesque figures lies in their ad similitudinem reformulation of the Byzantine panel. The composition provides an increased emphasis on the core motif turning the crucified Christ into the focus of attention (Figure 15.3). This is due to the framing supplied by the supporting figures attached to the repoussé silver ground and located on both sides of the cross, which divides the field into four panels. Even if the figures seem to have been created as appliqués, given that their size is consistent with the spaces delimited by the cross, and that Christ’s nimbus forms part of the repoussé ground, it becomes apparent that the figures were precisely conceived for such a composition. Nonetheless, the Christ figure’s body sways, breaking the unbending symmetry of the programme. This refinement may be attributed to the Romanesque artist’s wish to render the figures with a strong expressiveness. Accordingly, pathos is achieved by facial expressions and gestures that show emotional attitudes and dramatic poses. At the same time, these gestures and grimaces contrast with the harmonious intentions of the carefully balanced composition. Even more revealing, perhaps, is the artist’s tendency to distort the proportions of some body parts, especially heads and hands, as some sort of reinterpretation of the Byzantine ivory, where bodily schemata were accurately designed following the Byzantine canon of proportions.

Many scholars have found close parallels between the Romanesque crucifixion from Jaca and that of the Cross of Ferdinand and Sancha from the treasury of San Isidoro in León (Museo Arqueológico Nacional, 52.340), as well as the Carrizo Christ (Museo de León, 13) and the so-called Calvary of Corullón (Museo de León, 8, 10, 273).16 I, however, am not convinced by such comparisons. Rather, I would suggest that the overall style of the carvings shows significant discontinuity with León’s ivory carving tradition. It should be noted that the artist’s tendency to naturalism and his particular treatment of volume create similar effects to those of other three-dimensional media, especially architectural sculpture. In his search for both intensely expressive figures and a balance of dramatic rhythms within a larger symmetry, the Jaca artist breaks with the schematic reduction of natural forms typical of León’s monumental crucifixes. On the contrary, as already noted by Charles T. Little, the figures reveal ‘an integrity associated with large-scale sculpture’.17 This point leads to another interesting suggestion, that the ivories served, in poses and gestures, as models for a capital that originally came from the missing cloister of the same convent of Santa María in Santa Cruz de la Serós (Figures 15.4 and 15.5). This capital features scenes of the Flight into Egypt and the Massacre of the Innocents and has been attributed to the hand of the master who worked the front face of the Doña Sancha sarcophagus (Benedictine monastery of Santa Cruz, Jaca). As a matter of fact, the ivories display a series of standard workshop style characteristics also visible in the works of the ‘Doña Sancha master’.18 These features include bell-shaped sleeves and wide, doubled triangular collars, almond eyes and flattened noses. The figures wear loose-fitting clothing that hide the body, and drapery which falls in parallel, trimmed folds with serrated edges. This suggests the ivory carver ostensibly was not only trained within the same environment, but also that he most probably worked within the same chronological framework as the sculptor (c. 1096/1097).

In this regard the artist was not unaware of other, coeval ivory productions,19 namely the ivory panels that decorated the Reliquary of San Felices from the monastery of San Millán de la Cogolla (c. 1100) (La Rioja, Spain) (Figure 15.6). This is particularly well evidenced by his technique of tracing the most elementary forms of body parts and clothing with sketchy lines, without dwelling on details. As S. Moralejo pointed out, this formal language derived from the visual experiences of the Saint-Sever Beatus (Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, MS. Latin 8878) and is also to be found in both series of ivory figures and panels from Jaca and San Millán. In my opinion, the ivories created for the Jaca panel provided the perfect testing ground to try out these aesthetic possibilities, which were to be later developed in sculpture in the mature Romanesque style from Toulouse to Compostela.20 This set of ivories form the plastic expression of a renewed vocabulary built upon linear stylisation, and they might have played a major role in the assimilation and dissemination of this new language, especially by the late 11th and early 12th centuries, when later manifestations of Bernardus Guilduinus’ sculpture in Jaca introduced effects associated with minor arts.

The transfer of models, the use of formulas that were fairly typical in pictorial arts and especially in miniatures (e.g. the cloud-like undulations of the upper ivory figures), and the widespread affinity with other artistic techniques together reveal an undeniable degree of complexity in the creative process of the Jaca ivories’ carving. This interwoven dialogue between the arts was crowned with the addition of the bejeweled frames. Their decoration in silver-gilt pseudo-filigree and cabochons bears a close resemblance to a number of objects associated with the French abbey of Saint-Foy of Conques, including some fragments in the ‘A’ of Charlemagne, the so-called Pentagonal reliquary, the portable altar of Abbot Bégon III and the reliquary of Pope Paschal II, all in the abbey’s treasury, which suggests that the frames were produced in the same artistic orbit (Figures 15.7, 15.8, 15.9 and 15.10).21 Around 1100, the well-known Abbot Bégon III set up a new atelier of goldsmiths in order to carry out several commissions, including many reliquaries of the True Cross. Its productions are characterised by the use of silver instead of gold, as well as by the reuse of highly valued materials. They display a distinctive pseudo-filigree technique that creates complex visual patterns through specific vegetal and geometrical motifs, inviting comparison to the two diverse foliate patterns in the Jaca plaques. These and certain other features, such as the arrangement of the cabochons, their reinforcement by twisted threads, the use of slightly grainy tubular threading, and the highlighting of the edges of the frames with two larger, twisted threads, all link the silver-gilt frames from Jaca closely to the Conques workshop.22 Even the fascinating presence in one of the frames of a cloisonné enamel, which appears to be one of the earliest surviving examples of this technique in Aragon, may be better understood in comparison with the cloisonné enamels of the ‘A’ of Charlemagne, specifically in terms of its colour scheme and its floral motifs’ alveolar design.23 Perhaps this may be explained by the close political and monastic links between the French abbey and the Kingdom of Aragon that argue for the creation of such reliquaries for affiliated communities by goldsmiths based in Conques, or perhaps travelling goldsmiths in monastic employ.

After Sancho Ramírez’ death in 1094, the early reign of his son Pedro was still focussed on the conquest of the Muslim-held lands, especially the emblematic city of Barbastro located on the border of Muslim domains. In 1063, when King Sancho had briefly won Barbastro back from the Moors, he granted it to the Bishop of Roda. It was not by chance that between 1097 and 1100, and especially during the military campaign for the Conquest of Barbastro, King Pedro strengthened the kingdom’s affiliation with the great abbey of Sainte-Foy de Conques, which was led at that time by Abbot Bégon III.24 The exchange of monastic personnel is well documented since Pierre d’Andouque, formerly a monk at Conques, was bishop of Pamplona from 1083 to 1115. In addition, his contemporary Poncio, another former monk of Conques, was appointed Bishop of Roda in 1097 and two years later he hastened to request that Pope Urban II confirm the translation of the see from Roda to Barbastro.25 It is highly significant that some months prior, in this same year, King Pedro had promised to donate to the abbey of Conques the first mosque of the city of Barbastro, even before its conquest.26 At that time, the links between the abbey of Conques and the papacy appear to have been very close, as evidenced in Pope Paschal II’s donation of relics of the lignum crucis to the abbey in 1100. This donation was probably made by April 1100 when a papal brief issued by the same Pope Paschal II and addressed to Bishop Poncio acknowledged the translation of the see from Roda to Barbastro. In fact, we know that some months later, on 26 June 1100, Bishop Poncio visited the abbey of Conques in order not only to consecrate the portable altar of Abbot Bégon III, but also to place there the relics of the True Cross27 (Figure 15.9). It was within this context that Bishop Poncio might have communicated Felicia’s commission and entrusted it to the workshop active in Conques at that time. This key example may not have been the last artistic exchange between the Kingdom of Aragon and the Conques ateliers. In this regard, the so-called reliquary-casket of Saint Valerius from Roda de Isábena (Huesca, Aragon) should be taken into consideration, since enamels have been attributed to Abbot Boniface of Conques’ workshop (r. 1107–a. 1121).28

Despite the general assumption that the panels functioned as book covers for a missing gospel book,29 not only is there no material or documentary evidence for the existence of such a manuscript, but also the wood support from the plaque with the Romanesque figures seems to suggest it was remounted at a later date.30 At the same time, the two plaques do not have any visible means of attachment to a book and they lack the characteristic micro-tunnels of Romanesque bindings.31 On the contrary, since there has been no formal consideration of the silver-gilt frames in connection with Bégon III’s monastic goldsmiths’ atelier, no one has taken into consideration the other works from Conques that functioned as reliquaries, although the possibility that the plaques functioned as book covers, or as another sort of votive object, cannot be entirely ruled out given the later remounting of the wood support.

The artistic response to the arrival of eastern fragments of the True Cross in the Christian kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula and elsewhere in the Latin West during the 11th century was generally manifested in the creation of reliquaries that betray a close adherence to Western artistic traditions, such as caskets and crucifixes. As a result, it is rarely considered that among the surviving reliquaries of this early date, one may have been created with the intention of emulating a Byzantine model. Around 1160, one observes a Western interest in copying Byzantine reliquary forms, as shown by the renowned Stavelot Triptych (The Morgan Library and Museum, AZ001).32 Yet, in this context it is worth remembering a notice from the Vita Bernwardi Episcopi Hildesheimensis of the German chronicler Thangmar, which records that having received a particle of the True Cross from Emperor Otto III, Bishop Bernward of Hildesheim created a ‘container (thecam) richly decorated with gold and stones in qua vivificum lignum includeret’. Even if Holger Klein reads cautiously the uncommon term ‘theca’ as an indication that the reliquary ‘was in some way based on a Byzantine exemplar’ and suggests a cruciform reliquary, I am inclined to think that it could also refer to something similar to a box or a casket emulating, perhaps, the model of a Byzantine staurotheke.33 Given the apparent remounting of the Jaca plaques, the identification of a specific Byzantine model proves difficult, even if its shape recalls other 11th-century Byzantine examples, such as the Reliquary of the True Cross from the Treasury of San Marco (Santuario, 75) or the Staurotheke of Svanéti in the monastery of St. Kvirike and St. Ivlita (Svanéti, Georgia). In the latter respect, we ought not to forget that both silver gilt plaques could be also arranged in the shape of a box, similar to the aforementioned reliquary of Pope Paschal II from Conques (Figure 15.10) or the reliquary-box with the Crucifixion from the treasury of Maastricht Cathedral of the first half of the 11th century (Musée du Louvre, Département des Objets d’art, MR 349).

In such a scenario, the dismantled Byzantine ivory panel and the Romanesque figures could have been rearranged at Conques in a manner inspired by the appearance of a Byzantine staurotheke, not with the aim of adapting the object to Eastern ceremonial practices, but to use the distinctive devotional function of this format in order to serve a sacred purpose within Western liturgical practices, especially those connected to Good Friday, when the solemn ceremony of the Adoratio Crucis was performed, and especial prayers were offered on behalf of the deceased.34 It would justify the mysterious repetition in the Crucifixion theme. In fact, a closer look at the Romanesque ivories reveals something more akin to a lay mourning scene. Not only the absence of haloes, but also the sorrowful facial expressions and gestures of the figures in the upper zone, who touch their cheeks, and the Virgin on the left who grasps her belly, almost as if her pain was objectified, refer other later examples of mourning scenes, as in the Sarcophagus of Donna Blanca in Nájera (Figure 15.11). In this regard it should be mentioned that the convent of Santa María of Santa Cruz de la Serós, the recipient of Felicia’s donation, would become a centre exceptionally protected by the queen and her husband, as well as by king Sancho’s grandmother, Donna Sancha de Aibar, and his sisters, Teresa, Urraca and Sancha, who had already died by the time of the donation and who had chosen to be buried there.35 Consequently, the reliquary might have served a double function, as a devotional and commemorative object that was offered in fulfilment of the queen’s desire to praise the dead and keep alive the memory of her closest relatives, especially within the celebration of the Good Friday veneration of the cross.

I would like to thank Manuel Castiñeiras and Charles T. Little for their scientific guidance. I am indebted to John McNeill and Richard Plant for their help in the final edition of this text. I am also grateful to Julia Perratore for reading the draft and making helpful comments. I gratefully acknowledge use of the services and facilities of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. This research was supported by a MICINN FPI research grant and the results are fruit of the research developed for my PhD Thesis: Promoció artística femenina a l’Aragó i Catalunya (segles XI-XIII) within the project Artistas, Patronos y Público. Cataluña y el Mediterráneo (Siglos XI-XV)-MAGISTRI CATALONIAE (MICINN-HAR2011–23015).