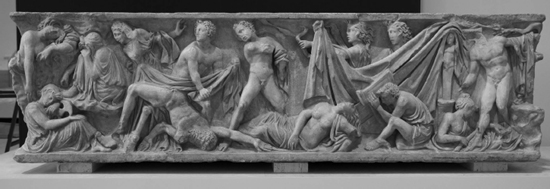

Figure 19.1

Madrid, Museo arqueológico nacional; Husillos sarcophagus (John Batten Photography)

Dissecting the twists and turns of artistic production in the Middle Ages is a challenging task. The multiple elements involved in the development of Romanesque art in Spain at a time of great invention and experimentation only serve to exacerbate this problem.1 In an attempt to pinpoint some aspects of ‘process’, this paper will focus on one medium, relief sculpture; on one period, the early 12th century and on two specific areas of enquiry. First the possibility of an ‘umbrella’ level of direction emanating from the papacy, and second the agency of artists who may have intersected with multiple ‘patrons’. The former relates to the mechanics of the implementation of reform. The latter considers the ways that artists may have dealt with such direction, which left room for interpretation by local recipients and for creative artistic responses to archetypes.

The idea that papal legates might have exercised artistic agency in the Iberian Peninsula from c. 1060 to c. 1100 formed the subject of an earlier paper, where I provided a narrative view of that process based on an accumulation of circumstantial evidence.2 It shows papal legates were present on significant occasions and played a key role in networks. As a prelude to the main subject here, I wish to deploy a historical and social context: a friendship circle, or réseau, associated primarily with Pope Gregory VII (1073–85), although it had roots in earlier papacies and continued long after the death of Gregory VII.3 This social network was formed by a closely managed group, whose members worked across institutional and political boundaries to form reciprocal relationships. Unlike the linear routes of ‘pilgrimage road’ art theory, this model of papal agency mirrors the circulation of artistic ideas, emphasises collaboration and nuances issues of precedence. The network grew over the last quarter of the 11th century, when it also supported the introduction of the Roman liturgy into the peninsula. It promoted a new generation of reformed churchmen and recruited like-minded supporters, so that by 1100 the web of connections had thickened and deepened. At the heart of papal artistic policy, as it was disseminated in Spain through this circle, was the use of Roman sarcophagi, both Pagan and Christian, as appropriate sources of artistic inspiration.4 Serafín Moralejo has shown that sarcophagi were central to the development of Romanesque sculpture on capitals and corbels in Spain, and demonstrated how figurative poses, particularly those of the Roman sarcophagus at Husillos, were adapted to architectural forms (Figure 19.1).5 I maintain that their role was even more important, and that they were identified as a suitable stimulus for diverse mental processes, technical, compositional and conceptual.6 The policy enabled papal legates to retain a degree of control over local projects and to guide the available artistic expertise without imposing oppressive restrictions. Such a differentiated and subtle approach fits with that adopted for liturgical change, which also looked to antiquity for its rationale.7 Sarcophagi not only directed artists towards archetypes from the period before the Muslim invasion, but avoided idolatrous associations with temples and freestanding sculpture. Within those limits, however, any type of sarcophagus seems to have been admissible as a source of inspiration, and the permitted responses to the subject were remarkably varied.

During the second half of the 11th century the popes identified men who could champion reform. In the 1060s Hugh Candidus from Remiremont, the legate of Pope Alexander II, began to establish relationships within the peninsula. His arrival was probably prompted by a conjunction of the temporary conquest of Barbastro (Aragón) in 1064, and by the death of Fernando I in 1065 and consequent instability in León and Castile. Both events were characterised by potential access to immense wealth. Hugh’s legateship continued until 1068 and was renewed in 1071, during which time he built networks across Catalonia and Aragón, introducing the Roman liturgy to at least one site in Aragón. This early phase of ecclesiastical reform does not seem to have given rise to a particular visual expression or formulated a ‘visual manifesto’.8 Cardinal-Bishop Gerald of Ostia, the great Cluniac canon lawyer, continued the work begun by Hugh and was appointed legate to Spain in 1073. In that year he excommunicated a rival claimant to the see of Burgos-Oca and confirmed Bishop Jimeno (d. 1082), who was to remain an important supporter of reform. Gerald may also have helped arrange Alfonso VI’s gift of San Isidro de Dueñas to Cluny in 1073, a transfer that was confirmed by Jimeno.9 This was the first of many gifts to Cluny that were part of a complex reciprocal relationship involving intercession for Alfonso VI’s family at Cluny.10 It foreshadowed the king’s conspicuous generosity towards the abbey, culminating in the large quantity of gold that helped to build Cluny III. That gift may be the best-known example of such an exchange, but it was far from the only transaction that linked sites and individuals within the friendship circle. We should envisage a frequent exchange of precious metals and luxury goods in return for spiritual rewards and international status. Another example of gifts and friendship saw Bishop Peter of Pamplona welcomed into the Cluniac fold between 1094 and 1104, after he had brought largesse from the conquests of Pedro I.11 Guidance on matters liturgical and artistic may have been amongst the less tangible benefits that came into the peninsula in return for the spoils of negotiated peace and war. The artistic expertise that can be seen on both sides of the Pyrenees may have travelled along the same routes of amicitia, perhaps in the form of craftsmen tied to members of the network.12

The first discernably visual phase of the Gregorian Reform can be detected during the papacy of Gregory VII, when the implementation of papal policy was carefully managed. The two dominant figures during this first phase were Amat, bishop of Oloron and, from 1089, archbishop of Bordeaux (d. 1101), and Richard, abbot of Saint-Victor of Marseille and, from 1106, archbishop of Narbonne (c. 1121). Amat began his career as a reformer in Aquitaine, where he was appointed legate by Gregory VII in 1074.13 He may have been a Cluniac and was possibly a protégé of Gerald of Ostia.14 Amat’s sphere of activity in the peninsula encompassed Aragón and Navarre, and, in accordance with Pope Gregory’s preferred management method, Amat shared this territory, his partner being Abbot Frotard of Saint-Pons-de- Thomières, who had a more permanent responsibility for the regions.15 Both were probably involved in liturgical reform, as Juan P. Rubio Sadia has traced elements in the liturgical manuscripts of Aragón from Narbonne, the diocesan see for Saint-Pons-de-Thomières; from Auch, the diocese to which Oloron belonged, and from Bordeaux.16In 1083 Frotard introduced two influential ecclesiastical protégés into Navarre, Peter of Rodez, a monk of Conques, who was preferred as bishop of Pamplona, and Raymond, who became abbot of Leire.17 Frotard worked closely with King Sancho Ramírez, and together Amat and Frotard may have helped to negotiate the marriage in 1086 of Pedro, the son of Sancho Ramírez, to Agnes of Aquitaine. Women were also an important aspect of exchange across social networks. Both Amat and Frotard had access to Roman sarcophagi, especially those of Late Antique date. The feature singled out for use in Aragón and Navarre was the chrismon, which was common on ancient sarcophagi across Aquitaine, Catalonia, Toulouse and could even be found near Saint-Pons in Rodez. Adapted as a ‘speaking chrismon’ with added letters, the motif was carved over church doorways on both sides of the Pyrenees, where it probably signified a seal of papal protection.18 Although Saint-Pons was in an area associated with marble carving, Frotard does not seem to have been in a position to introduce marble sculpture into Aragón or Navarre.

Amat’s counterpart was Richard of Saint-Victor of Marseille, a member of the comital family of Millau, a county whose territory lay east of Conques and Rodez. A more senior figure, Richard, was made a cardinal-priest in 1078, and in the following year he succeeded his brother as abbot of Saint-Victor in Marseille and was made a legate by Gregory VII. The pope assigned him a major role in the implementation of the Roman liturgy in León and Castile, and Richard forged a good relationship with its king, Alfonso VI, one which seems to have lasted until the king’s death in 1109. Richard and Amat were thus working as papal representatives at some remove from their own institutional areas of interest and in Spanish regions that were not immediately contiguous to them. Such careful checks and balances were typical of papal policy from the time of Gregory VII. This approach may have been particularly important in Richard’s case, as not only did he have a considerable family network across the Rouergue and Provence but much of Catalonia had been reformed from Saint-Victor de Marseille, and the monastery had acquired a significant number of possessions there, including Ripoll. Under Richard’s legateship the Roman liturgy was finally established in León and its introduction was confirmed at the Council of Burgos in 1080. Gregory VII also used Richard in 1083 to curb Cluniac ambitions at Saint-Sernin in Toulouse, where he employed rather blunt methods to reinstall the canons.19 Alfonso VI relied on him at the 1088 Council of Husillos in an attempt to settle matters in Santiago de Compostela and in Osma. Richard may have subsequently helped to negotiate the marriage of Alfonso VI’s illegitimate daughter, Elvira, to Raymond IV of Toulouse some time before 1094.20 Although in some ways a controversial figure, Richard was briefly reappointed legate in 1101 by Paschal II, and his authority was further recognised when he was made archbishop of the sizeable archdiocese of Narbonne in 1106.

Collaboration between Amat and Frotard was mirrored by that between Cardinal Richard and Bernard of La Sauvetat. Bernard became abbot of Sahagún in 1080 and from 1086 was Archbishop of Toledo. Andrea Rucquoi has described Bernard as Richard’s ‘man’, but their relationship was largely determined by the dynamics of papal management.21 Bernard was a Cluniac, educated at Saint-Orens in Auch and at Cluny. He was sent to León with the personal support of Abbot Hugh of Cluny, and in background he had more in common with Amat of Oloron than with Richard of Saint-Victor. The partnership between Richard and Bernard was thus a highly successful example of the papal approach that set aside potential institutional rivalries in the expectation of greater goals. It was the hallmark of the friendship circle. Like Frotard, Bernard recruited immigrant churchmen from his home region. Several arrived initially to serve as canons in Toledo, but later went on to senior positions: Bishop Peter of Segovia, Peter of Palencia, and Bernard of Sigüenza were all from Agen, while Bernard’s successor at Toledo in 1125 was Raymond who, like Bernard, came from La Sauvetat.22

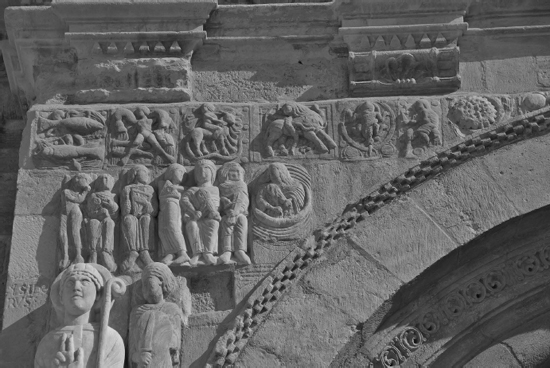

Richard and Bernard were equally complementary in their artistic milieux. The region around Marseille retained a rich collection of classical art, including sarcophagi, notably at Aix-en-Provence and Arles, both cities where Richard’s relations had considerable influence. Bernard, on the other hand, had access through his network to liturgical manuscripts from Auch, Agen, and Limoges, and his first monastery of Saint-Orens held a Late Antique sarcophagus, almost identical to one at Oloron (Figure 19.2). John Williams has shown a clear iconographic link between the sarcophagus at Saint-Orens and a capital depicting the Sacrifice of Abraham in the Pantheon at San Isidoro.23 As some aspects of the sculptural style found in the Pantheon may also derive from the same source, specifically the heavy facial and corporeal features and cap-like hair found on several capitals, Bernard may have advised Alfonso VI’s sister, Urraca, on the sculptural decoration. This style co-existed with the more classical approach that Serafín Moralejo has shown to be linked to the Orestes sarcophagus from Husillos (Figure 19.1), and thus to the Council of Husillos of 1088. Significantly it was Richard of Saint-Victor who presided over that Council, and he travelled with the archbishop of Aix-en-Provence. Aside from the presence of one of the finest sarcophagi in the peninsula, the venue had little to recommend it over Burgos, León or Palencia, so it may have been chosen for its artistic interest. The way that the capital with nude figures and serpents at nearby Frómista, only 25 km from Husillos, integrates responses to both types of sarcophagus could suggest that Richard and Bernard were also travelling with sculptors. The monastery of Husillos was in the territory of Alfonso VI’s childhood friend, Pedro Ansúrez, the Count of Saldaña, who, like Alfonso VI’s sister Urraca, may have had a particular interest in new works of art and architecture.24 Certainly many of the subsequent developments in the carving of capitals took place in churches located in his territory. Another innovation, personally connected to him, came from the monastery of Sahagún, and it is this sculpture that introduces the subject of this essay, the fashion for slab relief sculpture c. 1100.

In 1093 Pedro Ansúrez’s son, Alfonso, died and was buried at Sahagún in a tomb of white-grey marble, of which only the lid survives. As Alfonso was young, the tomb was probably posthumous. Alfonso VI’s queen, Constance, niece of Abbot Hugh of Cluny, died in the same year, so it is possible that the sculptor was asked to carve more than one tomb.25 Iconographically Alfonso Ansúrez’s sarcophagus lid looks to the early-11th-century Empire and to Cluniac liturgical intercession.26 In its gabled form it recalls Late Antique sarcophagi, but the decision to use marble and the use of a drill link it to classical sarcophagi and the renewal of techniques associated with them. As Moralejo noted, the faces of the flying angels, with fat cheeks and bulging eyes, recall other sculpted faces found near Palencia.27 However, marble carving was also practised at this date in the regions associated with Richard of Saint-Victor and Frotard of Saint-Pons-de-Thomières. Judging by patterns of survival, the most probable source for a sculptor with the technique necessary to carve marble would be Saint-Sernin at Toulouse, a possibility which meetings of the friendship circle in 1095 and 1096 would support. Against this, the portrait-like image of the deceased on the Sahagún tomb, and the ample use of script, suggest another possible source.28 Both features are found on a relief slab from Saint-Victor at Marseille, one that depicts their renowned mid-11th-century reformer Abbot Isarn. Often dated earlier, this piece is probably a retrospective memoria of c. 1100, celebrating the reforming ancestry of the abbots of Marseille.29 The relief from Saint-Victor and the Sahagún tomb lid also share an innovative approach to the relationship between the body and the slab, even if the results diverge. Whilst Alfonso Ansúrez appears to float towards the Hand of God that receives him into heaven, the equally individualised Abbot Isarn is flattened beneath the script that contains him.

The multiple references found on the tomb lid of Alfonso Ansúrez and on capitals in the Spanish kingdoms reflect connections between members of the friendship circle, which were becoming more complex around this time. The increased frequency of their meetings was matched by a change in the rhythm of artistic interaction. Richard of Saint-Victor attended the Council of Piacenza in March 1095, where most distinguished clerics of period, including Abbot Hugh of Cluny, gathered under Pope Urban II (1088–99) to set out a renewed reform agenda. The attendance list and canons have been pieced together from a variety of sources, confirming the presence of Archbishop Amat of Bordeaux and Abbot Frotard of Saint-Pons, along with Archbishop Peter of Aix-en-Provence. Bernard Reilly has argued that some Spanish representatives were also in attendance but others think that Richard presented their petition.30 Archbishop Bernard of Toledo was present, however, at the larger Council of Clermont in November 1095, accompanied by the Cluniac Dalmatius, bishop of Iria-Santiago de Compostela, who successfully requested the translation of his see to Santiago and its direct dependence on Rome.31 By now designated a permanent ‘native’ legate like Frotard, Bernard was with Urban II again the following year for the consecration of the high altar at Saint-Sernin in Toulouse.32 Other recorded attendees included Archbishop Amat of Bordeaux, Bishop Walter of Albi, Bishop Peter of Pamplona and Count Raymond of Toulouse, Alfonso VI’s son-in-law.33 Richard of Saint-Victor seems to have been absent, but Urban II confirmed Saint-Sernin’s independence, so vigorously established by Richard, at the Council of Nîmes shortly afterwards. The number of attendees with Spanish connections at the consecration may indicate communal, and reciprocal, support for the collegiate church.34 The Spanish clerics may have even been amongst the confratres mentioned on the altar’s inscription.35 Such bonds of amicitia would certainly help to explain the artistic dialogue between Toulouse and the Spanish kingdoms from the late eleventh century onwards.

The long papacy of Paschal II (1099–1118) opened in a spirit of optimism, after Pedro I of Aragón’s conquest of Huesca in 1096, and the success of the First Crusade in 1099.36 An ancient church in Huesca, renamed San Pedro el Viejo, was quickly ceded to Frotard’s abbey.37 Amat of Bordeaux, as papal legate, working again with Frotard of Saint-Pons, consecrated the mosque as a new cathedral.38 The focus of the circle appeared to be shifting eastwards in the wake of military success, following the acquisition of new wealth and perhaps expertise, which continued with Pedro I’s reconquest of Barbastro in October 1100. Even so Paschal II reappointed Richard of Saint-Victor as papal legate to León and Castile in that same year. Paschal may have retained a particular interest in the region, as in 1090 he was sent as Urban II’s papal legate to preside over a Council at León. His brief was to bring order to the vacant see of Iria-Santiago, to restore the archbishopric of Tarragona (in name at least), and, perhaps, to help Hugh of Cluny collect the arrears of his annual donation from Alfonso VI.39 In December 1100 Richard was to attend a Council at Palencia, a short distance south of Husillos, where he would work again with Alfonso VI and Archbishop Bernard of Toledo.40 On this occasion, he travelled with Ghibbelin, archbishop of Arles. Part of the business of the Council was to restore Braga to metropolitan rank, and its new archbishop Gerald of Moissac was in attendance. The Council of Palencia probably also ratified the election of Diego Gelmírez as bishop of Santiago de Compostela, as he confirmed one of its charters as bishop-elect. Gelmírez was now clearly a full member of the circle. His amicitia with Peter of Pamplona may date from their joint attendance at the Council, and possibly gave new impetus to artistic exchange between Santiago, Conques and Toulouse. Richard of Saint-Victor’s return to Palencia may also have been behind a renewed attempt to use Roman sarcophagi as sources of artistic inspiration and extend slab relief sculpture to the exterior of churches in the peninsula. Bernard of Toledo’s visit to Saint-Sernin in Toulouse in 1096 might alone be sufficient to account for this, but given Richard and Bernard’s probable artistic collaboration over a decade earlier Richard’s return to Spain seems a more timely catalyst.

Slab reliefs in stone and ivory were initially carved in Spain for interior spaces – tombs, liturgical furniture and shrines. The tomb of Alfonso Ansúrez at Sahagún constitutes the surviving example in stone, but others may have been lost. Morales, for example, writing in the 17th century described a tomb carved for the infanta Urraca (d. 1101) at San Isidoro as having a ‘very fine white marble’ chest, and being ‘strangely rich’.41 Within a short time relief carving came to adorn the exterior of buildings around doorways and to announce the church as domus dei, or as a reliquary in stone. The biblical model for such decoration was the Temple of Solomon (1 Kings 6; 2 Chronicles 2–5), which glittered with marble, precious metals and gems donated by King David (I Chronicles 292–5). Exterior slab relief sculpture may be found in Spain around 1100 over the south doorways at San Isidoro in León; over the transept doorways at Santiago de Compostela, and at Jaca cathedral, where it is now mounted on the exterior of the southern apse, and over the portal of the fortified collegiate church at Loarre.42 Some of this sculpture is carved on reused marble, a material that emphasises the earlier deployment of relief sculpture in interior funerary and liturgical spaces. Whether the repurposing of Roman marble slabs also carried imperial connotations at this period remains under discussion.43

The slab relief sculpture that decorates the exterior of the south nave portal of San Isidoro at León, known as the Portal of the Lamb (Puerta del Cordero), is the focus of the rest of this study. The reliefs appear in four different forms: a tympanum in two tiers; a row of zodiac symbols on separate slabs of grey-white marble; a set of slabs in a pinker-tinged marble-like stone depicting King David’s musicians and a soldier holding a shield and a sword; and two larger slabs sculpted with single figures in higher relief, one labelled as St. Isidore and the other traditionally identified as St. Pelagius (Figure 19.3). The coherence and date of the ensemble have long been a source of controversy, as elements may have been moved since their manufacture.44 I shall discuss the reliefs in five groups, as I will revert to Sauerländer’s view of the ‘tympanum’ and argue that it is an amalgam of two types of sculpture originally conceived separately45 (Figure 19.4). This opinion is strengthened by recent petrological analysis, which has shown that the lintel was carved in dolomitic limestone from the local Boñar quarry, whereas the upper reliefs – a clipeus containing the Lamb of God held by two victory angels, and two angels holding cross-staves – are of grey-white marble.46

A thick lime wash covers the slabs today and rather homogenises the tympanum, but differences between the slabs are clear in photographs taken by John Williams in the early 1970s.47 Other slab reliefs have clearly been moved into tympana at a later date, for example at Notre-Dame de Luçon (Vendée) and at Santiago de Compostela.48 Most significantly, however, this suggestion is confirmed by recent archaeological analysis by María de los Ángeles Utrero and José Murillo. Although John Williams argued that the reliefs were carved for their present position and purpose, more trimming is evident than he identified.49 The lintel is clearly cut unevenly along the upper edge, but damage is also visible on the slabs that bear angels carrying cross-staves (Figure 19.5). The tops of both wings on the right-hand angel have been cut; the halo has been trimmed across the top, and possibly its toes as well. The left-hand angel has been clipped at the top of its right wing. Williams pointed to some foliate carving continued from one of the marble pieces onto the lintel slab, but it would have been a simple matter to add such a feature when the sculptures were re-assembled as a tympanum. Most problematically these angels are now mounted to look outwards at the roll mouldings.50 Moreover the angel slabs at San Isidoro have no parallels on the capitals inside or outside the church. In style they are emphatically Toulousain, sharing hairstyle and features with the larger angels reset within the ambulatory at Saint-Sernin. Although the original disposition of the Saint-Sernin angels is uncertain – they may have been behind the altar table, or set into the walls of the sanctuary where they would recall other angelic members of the celestial liturgy as were later painted in Catalan apses, or have ornamented the shrine around the sarcophagus of St. Saturninus – they clearly originated inside the church.51 Like those at Toulouse, the San Isidoro angels are highly classical.52 Indeed the marble in which they were recut probably came from a Roman structure in León. Given these questions, it is worth considering other ways in which the San Isidoro angels might have been displayed. One possibility is that they formed part of an ensemble inside the church, perhaps around the shrine of St. Isidore, or even above the tomb of the Infanta Urraca. If so, the angels would have acted as psychopomps in the manner of the archangels on the tomb of Alfonso Ansúrez. Contemporary parallels for a funerary use are lacking, but given the experimental nature of early Romanesque sculpture and descriptions of other precious objects, such as a crucifix with a figure of Urraca kneeling at its base, this remains a possibility.53 The removal of Urraca’s body to the centre of the Pantheon, probably c. 1148 when Augustinian canons took over the double monastery, could explain Morales’s reference to the marble tomb, especially if part of its sculptural decoration had been removed. Alternatively, the panels could have been mounted in a gable over an earlier nave portal. Both suggestions assume that the angels were carved for San Isidoro, though they could, of course, be spolia from another site.

Similar questions might be asked of the zodiac panels now mounted as a frieze below the baroque cornice of the Portal of the Lamb (Figures 19.6 and 19.7). Is this their original position? What role do they play in the iconography of the portal? Although the rectangular slabs vary in size, shape and depth of relief, they clearly form a set, both stylistically and iconographically. They are full of invention and, as Serafín Moralejo noted, the sculptor drew on the figure of Orestes from the Husillos sarcophagus to create the naked male figure of Aquarius. The snakes held by the Furies on the same piece may have inspired the snake-like tails on the Capricorn and Leo panels.54 The sculptor who employed the pose from the Husillos sarcophagus to carve the naked figure on the showpiece capital at Frómista may thus have worked on the zodiac panels at San Isidoro, and perhaps on the ‘Sacrifice of Abraham’ at Jaca cathedral. It remains possible, however, that the sculptors were not identical but working with the same visual stimulus.55 It is possible that these panels always decorated the exterior of the portal, and some of the inscriptions on separate stones that once named each zodiac sign survive in a fragmentary state. Zodiac signs appear on the exterior of churches in other circumstances, and sculpted examples from the late-11th-century are found as metope friezes or metope-voussoirs in Aquitaine, notably at Saint-Pierre at Melle.56 In such cases the zodiac signs are thought to represent earthly or liturgical time, and they often appear in association with the labours of the months.57

Figure 19.6

León, San Isidoro; Portal of the Lamb, zodiac panels, left side (John Batten Photography)

An original interior function for these zodiac panels, in association with a tomb or shrine, is another possibility, as the inscriptions, cut into a different stone, could have been added at a later date. Zodiac signs sometimes appear on Roman sarcophagi, where they are thought to symbolise eternal fame and bliss.58 However, it is difficult to envisage the San Isidoro panels decorating a tomb, partly because of their size. Although the zodiac and angel panels are carved on slabs of the same white-grey marble, they are completely different in style and are unlikely to have been combined in a single work of art. Reliquaries provide another possible context for the zodiac reliefs. The St. Servatius reliquary from Quedlinburg (Saxony) preserves Carolingian ivory panels (c. 870) that depict the twelve zodiac signs above Christ and the apostles. Although this ivory box was not remodelled until c. 1200, it may have been the focus of attention in the early-11th-century as a gift from Emperor Henry II (d. 1024) to the abbey of Quedlinburg and its abbess Adelaide.59 Another link between zodiac signs and a reliquary can be found in the description of the shrine of St. Giles (Egidius) from Saint-Gilles-du-Gard, in the Pilgrim’s Guide from the Codex Calixtinus.60 Saint-Gilles-du-Gard was a neighbour of Saint-Victor at Marseille. The Guide describes how all twelve zodiac signs formed the second register on the great gold shrine, organised from Aries to Pisces, and how they were interspersed with gold flowers in the form of a vine. Regardless of the accuracy or otherwise of the Guide, it shows that such panels were perfectly appropriate on a major shrine. One unusual feature at San Isidoro suggests an awareness of liturgical furniture. This is the carving of small round circles on each plaque. Moralejo argued forcefully that these represent scattered stars, similar to those found in astronomical manuscript illustrations.61 If so, the sculptor or designer misunderstood their primary use in the manuscripts, where the most important stars are aligned with a defining part of each figure. If they were painted, perhaps in gold, these circles might equally imitate gilded nail-heads, of the kind that fix ivory or enamel plaques to reliquaries. Such attention to the physical construction of the panels would imply a methodical interest in making and artisanship. Ultimately, given the stylistic commonalities between the zodiac panels and the other reliefs on the Portal of the Lamb, they were probably all carved to decorate the exterior wall above the doorway. They may also have helped to denote the church as a holder of relics, and had other associations. Moralejo argued that the zodiac at San Isidoro was based on a sermon of the 4th-century bishop, Zeno of Verona, and that each panel had a moral dimension. He saw its appearance at San Isidoro as an assertion of Christian orthodoxy and as an anti-Islamic statement, and agreed with Williams’s interpretation of the tympanum.62 Astronomy and astrology were certainly controversial, and both Petrus Alfonsi from Aragón in the early-12th-century and, a decade later, Raymond of Marseille, a scholar from Richard of Saint-Victor’s region, felt obliged to write in their defence.63 Arabic treatises on astrology were also available in Toledo and, in accordance with Islamic thought, the zodiac might have been seen to confer talismanic protection on San Isidoro.

Below the zodiac panels a row of musicians is carved on six slabs cut from a different marble-like stone, with a pinker tone than that used for the angels in the tympanum or for the zodiac (Figures 19.6 and 19.7). Certain stylistic traits are shared between the zodiac panels and the musicians. The flowing hair and drapery of the female personification of Virgo is paralleled on some of the musicians; whereas the squashed features of another musician recall faces found on the Late Antique sarcophagus from Saint-Orens at Auch (Figure 19.2). The sculpted musicians appear to have always been intended for exterior use, and the panels probably never formed part of a tympanum but were always mounted above and to the side of the doorway. The current arrangement seems unbalanced, but this may be because some reliefs have been lost. This use of relief sculpture is paralleled by slabs of similar scale over the Porte des Comtes in Toulouse and on the Puerta de las Platerías at Santiago de Compostela, as well as by comparable developments in the Loire valley and Aquitaine.64 The panels at Santiago that are closest to the San Isidoro reliefs are those that were once over the Puerta Francigena, the north transept portal where pilgrims first entered the cathedral.65 Two scenes of Adam and Eve, God reproaching them and their Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, flank a slab depicting Christ in Majesty surrounded by the four evangelists. Although these sculptural vignettes, their frieze arrangement, and their repeated figures could be said to derive from the separate scenes found on early Christian sarcophagi, the subject found on so many sarcophagi, including that from Saint-Orens, Adam and Eve with the Tree of Knowledge, is oddly omitted or perhaps lost.66 Around this date sculptors in Aragón also experimented with slab relief carving. Framed plaques, used as metopes between the corbels on the south apse of Jaca cathedral, depict emblematic animals and figures. Antonio García Omedes has identified other blocks, now almost entirely eroded and embedded in the later central apse, which once carried images of the signs of the zodiac. These plaques may have originated as metopes from the earlier central apse, as he suggests, or they could have formed a frieze above earlier doorways on the west or south sides of the cathedral. The south doorway at Jaca has been reconstructed with a tympanum, but it is possible that the portal originally had only slab relief decoration including the frieze. It is likewise not entirely unthinkable that, before the construction of the porch, the west doorway at Jaca may have had slab reliefs. It is clear that the artists at San Isidoro were not working in isolation and that their experiments were paralleled at other sites. As Therese Martin has noted, there are stylistic similarities between the Portal of the Lamb sculpture and certain reset capitals in the apses at San Isidoro, which in turn have resonances with the capitals at Frómista and Jaca that Moralejo connected to the Husillos sarcophagus.67 These links suggest that the carvings were produced by craftsmen who worked across the friendship circle, and not for any single monarch, bishop or monastic order.

The sculpted figures at San Isidoro play a variety of instruments, while one wears a small crown indicating that these are King David’s musicians accompanying the psalms. Two musicians playing rebecs emerge from small circles surrounded by rough roll mouldings. As this gives the impression that they are playing their instruments amongst clouds, the musicians may also evoke a celestial liturgy. The reference to King David fits with the significant role the Old Testament monarch played in the memoria of King Fernando I, linking him in turn to the Carolingian and Ottonian emperors.68 This theme was particularly appropriate in a building whose prime purpose was liturgical intercession for the king.69 The Historia ‘Silense’, probably written at San Isidoro in the second decade of the 12th century, ends with a vivid description of the last hours of Fernando I: the king kneels before the altar of St. John the Baptist, and the relics of St. Isidore and St. Vincent, to recite the Davidic canticle Benedictus es Domine Deus Israel (I Chronicles 2910).70 The Book of Chronicles concentrates on the later part of David’s life and his death, and in particular on his arrangements for the worship of God. The association between Fernando I and the canticle had been established many decades earlier.71 This identification worked even during Fernando’s lifetime, as the Davidic canticle was included in the Liber Diurnus (fol. 179v), the book of prayers given to Fernando I by Queen Sancha, where an initial portraying King David resonates with that used for Fernando I on the dedication page.72 The correlation between King David and Fernando I was doubtless strengthened by chapter 29 verse 28 of I Chronicles that speaks of David dying ‘in a good old age replete with days, riches and glory, and that his son Solomon reigned in his place’, as this encapsulated the legacy claimed by Alfonso VI from his father.73 Another of the slab figures may also belong with the narrative of David: the soldier that uncomfortably abuts the figure of St. Isidore (Figure 19.8). Stylistically this relates to the group of musicians, but is usually considered separately. The figure is often described as an executioner of St. Pelagius, on the assumption that the figure paired with St. Isidore depicts Pelagius. However, the size of the soldier matches neither the musicians nor the large saints, and the way he turns suggests that he belongs in a narrative scene. Had he been carved in the same marble as the zodiac signs, he might have represented a planet, but given the importance of King David at San Isidoro, it is possible that he represents Goliath and that a smaller more lightly armed David has been lost.

The figures of St. Isidore and the saint that flank the doorway are a pair, carved by the same sculptor, who used discreet lion thrones to support each with only minor variations in the drapery and poses74 (Figures 19.8 and 19.9). St. Isidore has the accoutrements of a bishop-confessor with a crosier, episcopal cap and vestments, whilst the second figure has long wild hair, bare feet and carries a book in his veiled hand. The use of a veiled hand to hold a book indicates the figure was once a member of the clergy, in which case he is most likely to be the deacon St. Vincent, whose bishop charged him to preach, and not the boy martyr of Córdoba, St. Pelagius.75 It is true that painted figures of St. Isidore and St. Pelagius appear at the small remote Palencian church of San Pelayo, as Manuel Castiñeiras has noted, but a pairing of St. Isidore and St. Vincent at León fits better with the account of Fernando I’s death in the Historia ‘Silense’.76 St. Pelagius does not figure in Fernando I’s choice of intercessors in that text, but the relics of St. Isidore and St. Vincent play an important role in his last days. Combined with the reliefs of King David’s musicians, these large-scale saints suggest a mini-programme, closely tied to the memory of Fernando I and announcing the purpose of this royal monastery, which was liturgical intercession on his behalf. The Sacrifice of Abraham, carved in the lintel, continues this theme to the extent that verse 18 of the canticle ‘Benedictus es Domine Deus Israhel’ addresses the ‘Lord God of Abraham, Isaac, and Israel, our fathers’, after expressing thanks to God for the abundance (copia) that enables the temple (domus) to be built in His name. Thus the Davidic canticle provides a textual framework for San Isidoro. Not only is Fernando I an antitype of King David, and Alfonso VI an antitype of Solomon, but the church of San Isidoro is also a re-embodiment of the temple of Solomon built with the riches gathered by David. The immense wealth of the temple is expressed in verse 2:

Now have I prepared with all my might for the house of my God the gold for things to be made of gold, and the silver for things of silver, and the brass for things of brass, and wood for things of wood; onyx stones, and stones to be set, glistering stones, and of divers colours, and all manner of precious stones, and marble stones in abundance.

The emphasis on multi-coloured stones may even have suggested the three hues of stone found over the Portal of the Lamb, the yellow-brown limestone, the pinker stone and the white-grey marble. A specific reference in verse 4 to gilding the walls of the temple might have reinforced the decision to place the slabs across the walls, and the stipulation in verse 5, ‘all manner of work (opus) to be made by the hands of artificers (artificum)’, could have inspired the self-conscious artisanship displayed on the zodiac panels if the small circles depict gilt nail-heads. The decision to put zodiac signs over the doorway at San Isidoro may also allude to the last verse of I Chr. 29 that reflects on David: ‘With all his reign and his might and the times that went over him (temporum quae transierunt sub eo), and over Israel, and over all the kingdoms of the countries.’ The close dynastic identification with King David and King Solomon suggests strong local agency for the overall conception of the portal decoration, an impression that is reinforced by the long-standing importance of the canticle in the mythology of Fernando I. As Alfonso VI’s daughter Urraca did not claim the infantaticum, including San Isidoro, until after the death of her husband, Raymond of Burgundy in 1107, it is probable that Alfonso VI himself would have taken on responsibility for the infanta’s project in the meantime.77 As he had been close to his sister Urraca, he may have wished to monumentalise her devotion to the memory of their father, as well as giving visual expression to his own legitimacy over the enlarged kingdom of León-Castile.

The sculpture on the lintel, the largest slab on the portal, was carved in the same local limestone as most of the church (Figures 19.4 and 19.5). The sculptor – or sculptors – worked in an idiom that relates to some of the zodiac panels, for example the centre-partings found on Hagar and the Angel are similar to that of the surviving twin in Gemini (Figure 19.7), but he does not seem to have worked at San Isidoro long-term. The subject of this large relief is the Sacrifice of Abraham, which would have been familiar from many sarcophagi including that from Saint-Orens. As Francisco Prado Vilar has shown, this slab is a response to the ways narrative is displayed on pagan sarcophagi, specifically that at Husillos (Figure 19.1).78 In its size, rhythms and composition this relief reinvents the carving on the classical sarcophagus, whilst substituting a narrative of the Old Testament for the classical myth. The figure of Orestes is repeated cartoon-fashion on the Husillos sarcophagus: in the centre he carries out the murder of his mother Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthus, to the right he is driven to remorse by the Furies and to the left tormented by them even in his sleep. On the San Isidoro lintel Isaac appears three times: on the right, his mother Sarah watches him depart on a horse; once dismounted Isaac removes his sandals to make himself a fitting sacrifice, and in the central scene Isaac is on the point of being sacrificed. Whilst the other slab reliefs at San Isidoro derive generically from sarcophagi, the lintel is in explicit dialogue with the Husillos sarcophagus. The sculptor found a way of reinventing the whole sarcophagus relief that went well beyond the use of techniques and isolated motifs found after the Council of Husillos in 1088. As on the Husillos sarcophagus, ritual death occupies the centre of the space, creating a physical and narrative core for the design, and both the reliefs have a dynamic symmetry that is carefully balanced around that central scene. Although there is almost no stylistic engagement with the Husillos figures, the faces of the figures on the San Isidoro lintel share a certain bland sweetness with some of those at Husillos. There may also be an awareness of the Saint-Orens sarcophagus, which also includes Abraham’s wife Sarah in the scene, and an aedicule, although in that case it forms the tomb of Lazarus.79

The intellectual conception of the lintel is as subtle as the engagement of the sculptor with the physical form of the sarcophagus. Normally this image is emblematic and consists of only one abbreviated scene: Abraham about to plunge the knife into his son with an angel intervening and a ram waiting in the wings to replace Isaac. In contrast an exceptional extended version of the scene is found on the lintel. In the centre is the familiar core scene: Abraham about to sacrifice Isaac when an angel appears and offers a ram as a substitute. The additional scenes on each side precede the Sacrifice of Abraham chronologically and thus lead towards the centre. The figures of Hāgar and her son Ishmael are placed to Abraham’s right, balanced on the left by those of Sarah and Isaac. Williams sees the figures of Sarah and Hāgar as a representation of the Pauline Letter to the Galatians (chapter 422–31), where they stand for the Old and New Covenants, for the sons of the free descended from Isaac and those of the unfree descended from Ishmael. In the same text Hāgar is described as mount Sinai, whereas Sarah is Jerusalem. Consequently Williams, in common with most other interpreters of the tympanum, sees opposition, conflict and a negative view of Islam in this sculpture.80 For him it is a representation of reconquista. He reinforces this interpretation by highlighting a detail in the carving of Hāgar, for him a figure of luxuria and an exemplar of the lascivious nature attributed to Muslim women in Christian thought, because her left hand slightly lifts her skirt.

However, Williams also notes another aspect of the design which suggests that this may not be straightforward triumphalism: Isaac is unusually approaching from Abraham’s left, often considered the less favoured side, ceding the right side, the more favoured, to Hāgar and Ishmael.81 More significantly Hāgar stands very close to the angel, a proximity that recalls her two conversations with angels in the Book of Genesis. Hāgar is not a negative figure in the Old Testament; she is a foreigner and a servant, but not an enemy. Moreover Hāgar’s gesture is ambiguous: she lifts her skirt with only her left hand, not two as if dancing, and her left-hand side is closest to the angel. This suggests another possibility, a reference to a Midrashic tradition, which says that Abraham tied a garment to Hāgar to indicate her enslaved status. She had to drag this behind her as she walked amongst the mountains searching for water that she finally received from the angel Gabriel. This popular story intimates a change in Hāgar’s status, which subverts St. Paul’s juxtaposition of the enslaved and the free woman. If the sculptor had intended a simpler triumphalist reading of Galatians, a more obviously enslaved Hāgar could have been placed on the far left to contrast with Sarah on the far right. He could have included Mount Sinai, and placed Sarah outside the city of Jerusalem, not her simpler dwelling. He could have placed the angel on the other side of the ram. A more aggressive Ishmael could have been put closer to the centre as if threatening and in opposition to the submissive figure of Isaac. Instead Ishmael is placed on Hāgar’s right and shown riding in the wilderness on the point of leaving the scene. His body twists as he raises his bow and arrow, which he points upwards and away from the other figures. This depiction of Ishmael, as an archer, refers specifically to another biblical verse: ‘And God was with the lad; and he grew and dwelt in the wilderness, and became an archer’ (Genesis 2120). This biblical portrayal of Ishmael is again not negative but runs parallel to that of Isaac, like the symmetry of the sculpture. In Genesis Ishmael attends the burial of Abraham and is the father of twelve sons that beget twelve tribes, as was Jacob. His descendants are as God-given as Isaac’s, even though his mother is a bondwoman.82 Meyer Schapiro notes another non-biblical element in the central scene: the angel is presenting the ram and not merely pointing to it. He found this iconography mostly in Spain or the Languedoc and was able to relate it to both Jewish and Islamic texts but not to Christian ones.83 Taken together these details suggest a different interpretation of the lintel sculpture.

First, and most importantly, I want to suggest that the symmetry of the Abraham relief may indicate not opposition but unity under the rule of Abraham’s people. It represents the idea of negotiated reconciliation, and not the dominance of reconquest. This connects to I Chronicles 2930 to King David’s rule in Israel and ‘in all the kingdoms of the lands’ (in cunctis regnis terrarum). The covenant between God and Abraham, made possible by Abraham’s demonstration of faith, was a blessing for all the peoples of the earth and represented a bond with Abraham’s other descendants, the Ishmaelites.84 I do not intend this as some kind of idealised convivencia, but something closer to an inversion of the dhimma or pact, whereby other Peoples of the Book could be protected under Muslim rule provided they paid a tax and conformed to certain rules. Since the conquest of Toledo in 1085, Alfonso VI had ruled not only over León, Castile and Galicia, but also over much of the old taifa kingdom of Toledo. He now had responsibility for a mixed population, where Christians were at the top of the pyramid with a duty to protect the Jews and Muslims. As Prado Vilar has highlighted in this context, lacking a male heir with his aristocratic European queens, Alfonso VI promoted Sancho, his son by Zaida, his Sevillian concubine, as a member of the court, and by 1106 as his heir.85 The relief sculpture from the Portal of the Lamb seems to fit into this historical and political situation, after the Council at Palencia in 1101 but before the death of Sancho in 1108, during the years when a Leonese-Castilian version of al-Andalus still seemed viable.

The details of the lintel carving may suggest its agency. It seems probable that the ultimate patron was the king, as his sister, the infanta Urraca who had been the domina of San Isidoro, died in 1101. But the complex nature of this work suggests the involvement of others. Given the lintel’s dialogue with the Husillos sarcophagus, the sculpture may have been planned at the Council of Palencia in 1100, perhaps in front of the pagan sarcophagus. This return to the Husillos sarcophagus as a stimulus for creativity is a strong indicator of fresh guidance from Cardinal Richard of Saint-Victor. Pope Paschal II had given him renewed authority through his re-appointment as papal legate and an opportunity to revive his partnership with Archbishop Bernard of Toledo.86 Richard’s role in the friendship network could also have exposed him to theological debates around intellectual and artistic dependence on pagan culture, most notably those of St. Augustine.87 Julie Harris has shown how St. Augustine’s reading of the notion of ‘spoiling the Egyptians’ (Exodus 112 and 1236) in his De doctrina christiana, so popular with rhetoricians, could have been used to legitimise the repurposing of Muslim objects and buildings.88 It would have been equally suitable as a justificatory framework for stylistic, technical and compositional borrowing from pagan sarcophagi. Augustine says that when ‘the Christian severs himself in spirit’ from pagans, he could take their treasures ‘for the lawful service of preaching the Gospel’, and that it is also right to receive ‘their clothing’ (vestis) or practices (instituta) which should be converted (convertenda) to Christian use. This describes the process underlying the creation of the lintel, when both motifs and compositional elements from the Husillos sarcophagus were converted for a Christian narrative.89 The lack of any surviving manuscript of Augustine’s De doctrina christiana in Visigothic script suggests that such scholarly thinking was not indigenous. Bernard of Toledo might have known the text, as there was a 10th-century copy at Cluny, but Richard of Saint-Victor is a more plausible candidate. Not only was he surrounded by pagan sculpture in Provence, so would have had greater motivation to engage with this question, but, judging from the earliest inventory to have survived from the library at Saint-Victor, he had access to the De doctrina.90

Although Archbishop Bernard had considerable experience of negotiating with the Mozarabic population of Toledo and Cardinal Richard had direct contact with the city between 1088 and 1099 when his abbey administered San Servando on behalf of the papacy, it is hard to attribute the demonstrable knowledge of Jewish and Islamic scholarship in the lintel carving to them. Another possibility is the involvement of Jewish advisors at Alfonso VI’s court.91 A third possibility is the participation of educated men from Toledo, perhaps Mozarabs, perhaps Muslims, perhaps even converts to Christianity. Amongst these may have been the sculptors themselves. The prevailing assumption is that craftsmen were skilled but ill-educated artisans, although the sophistication of Caliphal ivory carvers suggests that this was not necessarily so. Such sculptors worked at the forefront of artistic exploration in form, style and composition and were responsible for much ingenious ‘Romanesque’ invention. Their formation is the subject of debate, but it is probable that some of these sculptors had been trained in the taifa kingdoms.92 If they came from Toledo, for example, this raises questions about their status, confessional identity and language. They may have been free, manumitted or unfree, Muslims, converts or Christians. Their world was one of shifting identities, lively debate and translation.

It may be worth recalling one notable case of a convert in this decade: the Jewish scholar Moses who became Petrus Alfonsi. He was baptised on the feast day of SS Peter and Paul in 1106 in the cathedral (previously a mosque) at Huesca, in Aragón. The occasion was sufficiently important for the bishop to baptise him, and for the king, Alfonso I ‘the battler’, to stand as his godfather. Petrus was then able to travel as far as England, to have access to libraries and intellectual circles from Canterbury to Malvern, and possibly to serve as physician to King Henry I.93 Although he had only moderate success as a teacher in France, his works have survived, from aphorisms and fables to astronomy, astrology and exegesis of both the Talmud and the Qu’ran. But it is his critique of Judaism – and incidentally of Islam – presented as a dialogue with himself, that received most attention in the Middle Ages.94 This world in which the lintel sculpture was created was one where conversion to Christianity opened doors and gave entreé to royal and ecclesiastical networks. Both the lintel and the zodiac panels suggest the involvement of someone with the breadth of knowledge of a Petrus Alfonsi, a command of both Judaic and Islamic scholarship, and an engagement with debates between the three religions. It is this dimension that gives the lintel sculpture its exceptional complexity. The role of such an individual, as advisor to the king, as translator for the sculptors, must remain the subject of speculation.

The Portal of the Lamb as a whole reflects an environment in which experimentation was allowed to flourish. The sculpture seems to emerge from a deep and lengthy dialogue, and the sum of the innovations introduced on the Portal of the Lamb remains our best guide to its agency. The over-arching typological narrative has solid foundations in the imaginative landscape of León, which was forged in the last years of Fernando I or in the first decade of Alfonso VI’s reign. Its re-invention on the portal suggests the close participation of the king, perhaps fulfilling a wish of his sister Urraca. The return to the Husillos sarcophagus as a stimulus for creativity implies that the old team, the king, Richard of Saint-Victor and Bernard of Toledo, had reunited. The execution of the scheme, however, represents a considerable creative leap in a number of ways. The use of slab relief sculpture on the exterior of a building was new not only to San Isidoro but also to the peninsula; only the small panels at Jaca may pre-date those from Portal of the Lamb. The clear precedent for this kind of sculpture, and for marble carving, is, of course, Saint-Sernin at Toulouse, but the sophistication of the programme at San Isidoro goes beyond the Porte des Comtes.95 The intersection between archetypes, materials, style and form in León is remarkably inventive. One of the keys to this phenomenon may be the movement of artists. These sculptors do not form a Leonese ‘workshop’, and they do not seem to have worked at San Isidoro for any significant amount of time before or after the completion of the Portal. Amongst surviving buildings, their artistic dialogue is with other innovative centres, with Toulouse, Frómista, Jaca and later with Santiago de Compostela. These sites may be on the ‘pilgrimage roads’, but that does not provide a plausible rationale for the sculptors’ arrival in León. This team, which may have worked together some ten years before, would have been carefully assembled for the project. The underlying stylistic connections between San Isidoro, Frómista, Toulouse and Jaca fit with the ecclesiastical network, the friendship circle in which Cardinal Richard of Saint-Victor played a major role. Other links can be found between León and Toulouse through the marriage of Raymond IV and Elvira, but only the network, bound together by gifts and counter-gifts, had the same breadth and depth as the artistic dialogue.96 Ultimately the bonds between the sculptors and their multiple patrons produced a complex self-aware work of art that continues to provoke debate.