In this chapter, we address how we analyzed data from an in-depth interview study of 20 older women from central Appalachia who had experienced and were surviving gynecological cancer. We describe the process we used to analyze the data from the older women’s in-depth interviews, which led to our publication in The Gerontologist (Allen & Roberto, 2014). Although this chapter focuses on these 20 focal women, we also used a family-level research design, which included data on an additional 33 individuals, all of whom were close family members (including biological, legal, and fictive kin). Briefly, the key findings from the study involved the women’s experiences with their cancer trajectory from symptoms to diagnosis to treatment. We found four patterns of post-treatment perceptions among the 20 women: (a) 11 women had a positive identification of being a cancer survivor; (b) four women were cautious and concerned that they were at risk for reoccurrence; (c) three women distanced themselves from an identity of being a cancer survivor; and (d) two women were resigned to the belief that cancer was taking their life (Allen & Roberto, 2014). In addition to this typology, we also found that all of the women acknowledged an inner strength often bolstered by their religious faith and the ways in which they navigated their cancer experience that transcended how they viewed their prognosis.

Our methodological choices were rooted in a bigger picture of how we conceptualized the research process, of which data analysis was one core component. We did not start the analysis process with the data. As feminist family scholars, we explicitly acknowledged our commitments to the research by identifying and scrutinizing its scientific and personal components. Our practice of data analysis, which we have developed over several years working in collaboration with one another and other feminist scholars, began with the integration of (a) the context of the study; (b) our feminist theoretical perspective; (c) the sensitizing concepts derived from the empirical literature; (d) the research questions that were generated from an examination of context, theory, and literature; and (e) the data we collected directly from the participants. After having gathered together and organized all of this material, the data analysis began. Next, we describe these components and then turn to a more detailed examination of how we analyzed the data.

Our investment in this project was rooted in personal and academic interests. Both of us have spent our careers studying marginalization in older families (for examples see Allen, Blieszner, Roberto, Farnsworth, & Wilcox, 1999; Roberto, Allen, & Blieszner, 2001). In addition, personal experiences have informed our work, to varying degrees. For example, the current study came about after Katherine’s mother died from ovarian cancer in 2009. Karen, who directs the Institute for Society, Culture and Environment (ISCE), a research investment institute at our university, suggested Katherine put her personal knowledge into a research topic on older women’s gynecological cancer, and provided an ISCE grant to pursue the study. As a principal investigator of the Appalachian Community Cancer Network, funded for more than 10 years by the National Cancer Institute and involving partners from five states in Appalachia, Karen provided resources and knowledge of the community context. Combining our respective expertise and personal investments in the study brought a more robust synergy to the project than what might have been accomplished alone.

Theoretically, our research is feminist, de-emphasizing hierarchal power dynamics in the research team and in the interviewer-interviewee relationship. Our commitments are to understand and ameliorate the oppressive conditions often facing marginalized populations.

We bring a heightened consciousness to data analysis, one that reflects the lived experiences of our participants as well as our own. We believe that research arises from the researcher’s own experience of the everyday world (Smith, 1993). Claiming our stake in the research endeavor makes for a richer portrayal of the worlds we try to understand (Richardson, 1997). Thus, as the analysts (in terms of our own perspectives and interactions with one another), we are as much a part of the analysis as the participants. The reflexivity involved in a feminist approach is key to the conscious scrutiny we bring to data analysis and knowledge production in family science and our sister discipline of gerontology (Allen, 2000, 2016). We also often combine more mainstream theories such as a life course perspective (Elder & Giele, 2009) with critical and constructivist feminist perspectives (Sprague, 2005) to address individual, family, and social-historical time.

Our review of the literature (see Allen & Roberto, 2014) demonstrated that people in rural Appalachia suffered health disparities in under resourced communities. Older women in rural Appalachia carry a disproportionate share of the cancer burden, including greater incidence rates of primary cancers, such as cervical cancer (American Cancer Society, 2017; Wilson, Ryerson, Singh, & King, 2016). When cancer diagnosis occurs, physical and social environmental factors of this region impose major barriers to treatment and their use of supportive services. Lack of transportation, low income, low education, poor housing, lack of health insurance, few health care options, and limited access to oncology and support services (e.g., mental health) are serious risk factors for rural cancer survivors (Behringer et al., 2007; Lyttle & Stadelman, 2006).

At the same time, Appalachia is a region with a strong sense of self-reliance, traditionalism, religiosity, and family ties (Coyne, Demian-Popescu, & Friend, 2006; Schoenberg et al., 2009). Although family relationships are considered a bedrock of social support in helping individuals with cancer survive this devastating illness, assumptions about families in Appalachia are challenged by research on changing family structures and dynamics in the context of geographic isolation and economic limitations (Beesley et al., 2010; Schlegel, Talley, Molix, & Bettencourt, 2009). Shifts occur in the quantity of family members available to help women and the quality of those relationships (Allen, Blieszner, & Roberto, 2011). Older female cancer survivors are likely to be dealing with multiple illnesses and responsible for family members themselves. Their quality of life can be threatened by social and psychological stress caused by family members as well as by perceptions of how their cancer is affecting family members’ lives (Bevans & Sternberg, 2012; Duggleby et al., 2011).

This combination of gender, age, geography, and family in the literature led to our research questions: (a) How do older women in rural Appalachia describe their experiences with diagnosis and treatment from gynecological cancer? (b) How do older women experience living with cancer post-treatment? These questions led to the interview questions we specifically asked of participants, which guided them through their cancer journey, from the onset of their cancer and how their relationships and activities had changed since diagnosis.

The 20 older women cancer survivors were our focal research participants (Allen & Roberto, 2014). We began data collection by having each woman respond to a structured demographic questionnaire, two mental and physical health-related questionnaires, and an open-ended interview, which averaged 104 minutes. The interview questions invited the women to think and talk more deeply about their own actions, motivations, and experiences. Our use of face-to-face interviews was vital in establishing rapport and creating a climate of trust that assured the older woman that her cancer story would be treated with the respect and care it deserved. Although telephone interviews are also effective (Goldberg & Allen, 2015), we wanted to physically demonstrate our investment of time, attention, and credibility. This attention to participants at the front end of the process was essential for helping ensure that the analysis reflected the way the participants wished to present themselves.

Because we were guided by research questions and used sensitizing concepts (Blumer, 1969) such as cancer as a journey and the importance of family and fictive kin relationships from the outset of the study, our approach to data analysis was both deductive and inductive (Daly, 2007; Gilgun, 2016). This methodological approach fit well with critical and feminist theories that offer an emancipatory framework with the goal of challenging the status quo and empowering marginalized individuals who often live on the edges of mainstream society (Allen, 2016; Gilgun, 2016).

We used content analysis, a well-known qualitative methodology that undergirds grounded theory strategies. Content analysis follows the constant comparative steps of open, focused, and selective coding (Charmaz, 2006), although the labels for each of these progressively narrowing strategies of data reduction may vary depending on the how to text that the analyst follows (Bogdan & Biklen, 2007). Our analytic method was a process of generating and reading text over and over again. Seeing, hearing, writing about, and reconfiguring the participants’ words and experiences are the skills we relied on as qualitative researchers in coming to understand what our participants were saying, feeling, and reflecting about. Our method of data collection and analysis is akin to many variations of qualitative research, and we use the standards of rigor, transparency, and full disclosure when communicating our work to others (Goldberg & Allen, 2015). In summary, our analytic approach engaged the data (i.e., the participants’ perspective on their own lives), before, during, and after it was collected through the use of the scholars’ tools of theory, empirical literature, reflexivity, and moments of insight forged in a collaborative process.

After each interview, a professional transcribed the audio-recorded session into Microsoft Word documents for each of the 20 cases. Katherine reviewed all of the transcripts for accuracy by listening to each audiotape and comparing it to the transcribed content. In addition to correcting minor typographical errors on the transcripts, Katherine inserted pseudonyms into each transcript. The 20 older women’s interview data resulted in 583 pages of mostly single-spaced transcript (on average 30 pages per person, with a range of 20 to 38 pages). This count included 443 pages of interview data and 140 pages of supplemental material (handwritten answers to interview guide questions, responses to the demographic questionnaire, responses to the depression scale, and numeric responses to the health status questionnaire). Thus, we were working with many pages of data, mostly in Word files so they could be read, marked, and analyzed either on the computer (typically used by Karen) or printed and marked on by hand (typically used by Katherine). We printed hard copies of all interview material and kept them in three-ring binders; the Word files were also stored on the computer.

In addition to the in-depth interviews, we developed a series of three family genograms (McGoldrick, Gerson, & Petry, 2008) for each woman’s caregiving and health-focused relationships before, during, and after cancer treatment. Our graduate research assistant, Emma Potter, used a computer program (GenoPro; www.genopro.com) to construct the family genograms, which were stored on the computer and also printed and kept in three-ring binders. The genograms allowed us to visualize the cancer survivors’ family relationships (e.g., ties to biological, adoptive, and step kin), and how they linked to their life circumstances and medical history. For the purpose of the analyses reported in our 2014 paper, we used the genograms to visually inform our understanding of the women’s relationships across the cancer trajectory and remind us about the independent and interrelated roles others played in the women’s cancer story as family, friends, and others entered and sometimes exited the women’s daily lives. Figures 5.1, 5.2, and 5.3 show a participant’s (Helen) three pathways at different points in time.

To systematically analyze the data for the 2014 publication, we used grounded theory procedures (i.e., open, focused, and selective coding), which provided flexible guidelines for developing a coding scheme that reflected the entire data set (Bogdan & Biklen, 2007; Charmaz, 2006). However, there was a lot of effort that happened behind the scenes before the actual coding and analysis process began. As we have done in previous collaborations, we decided ahead of time which one of us would take the lead on a publication (Katherine, in this case), and that person then took responsibility for directing the coding and analysis. The other person (Karen, in this case) provided the back up and served as the devil’s advocate by independently reading the complete transcripts in chunks (about five at a time) and then offering insights, challenges, and new concepts/codes each step of the way. Often, we go back and forth on publications, where one of us takes the lead on the first paper, and then the other person takes the lead on the next paper. This way, we share the workload and our expertise, and both of us come to learn the data inside and out. We also tend to follow this pattern of sharing the lead when working with our graduate students and colleagues on other projects.

Thus, as first author, Katherine conducted all of the interviews and verified all of the audiotapes; this process familiarized her with the entire data set three successive times. She then read all of the transcripts again (for a fourth and fifth time) to prepare the initial drafts of the coding scheme. Karen read a random selection of five transcripts (chunks) through each iteration of the development of the coding scheme, thus providing an independent source of insight into how the scheme was developing. Ultimately, Karen also read all of the transcripts multiple times but as first author, it was Katherine’s responsibility to guide the process. Because we have worked together on several research projects over many years, we have developed this system of conducting data analysis that feels second nature to us.

As we detailed in the beginning of this chapter, we brought many ideas to the corpus of data—beyond the transcripts themselves—and this initiated the open coding process. It is helpful to picture the documents before us as we sat down to conduct the initial open coding, having already read and reread the body of data multiple times. Along with the transcripts, we also had in front of us (either in paper or on the computer) the list of guiding research questions and theories, as well as the specific interview questions asked of the women (e.g., Please tell us about your cancer story. Who are the important people in your life? Who are the people that have supported you in dealing with cancer?). All of these materials helped to sensitize us to how we were interacting with the data. To do the initial open coding, Katherine wrote in pencil and colored markers on each transcript any concepts, hunches, insights, and reminders of ideas to return to (see Figure 5.4, which highlights a transcript page in which faith in God, having a positive attitude, and doubt about getting a diagnosis were noted). After she read all of the data in this unstructured way, she went through them again and generated a typed list of ideas that were common across the entire data set, as well as some ideas that were unique to each case. These ideas included a range of topics, such as (a) sources of information in learning about cancer; (b) how I now take care of myself since being treated for cancer; (c) religious beliefs and practices; (d) family crises and hardships during and after treatment; and (e) the quality and quantity of my support network.

Although at this stage we did not analyze the genograms in a formal way, they provided a valuable visual representation, of particular interest to Karen, that helped us sort out how the women viewed and talked about their relationships. For example, we saw very few major changes in the size or composition of the women’s family system throughout their cancer journey. More commonly, we saw changes with the focus and intensity of the supportive roles family members played. Relationships weakened and strengthened; some changed temporarily, while others were permanently altered. Women often found short-term ties (e.g., the presence of a cancer buddy) during the treatment and recovery process and such arrangements were more important than the help they regularly received from a spouse or adult child. Cancer often accompanied both personal and network stressors and was not experienced in a vacuum. That is, cancer was not a singular event that occurred at one point in time, but the women’s diagnosis of cancer often came on top of other diseases and conditions, and into a family system with multiple problems (e.g., an adult child’s incarceration) and challenges (e.g., lack of transportation; Allen & Roberto, 2014).

Another preliminary strategy we used to learn the data and to commit ourselves to a formal coding scheme was to write a brief case synopsis from each of the women’s transcripts, and then highlight major points that we anticipated would make a difference in the next stage of coding. These case synopses were typed into a Word file containing all 20 cases (approximately one page per case). Our initial observations about the women were key in understanding how women reconstruct their kin networks and ultimately informed our preparation and understanding of the genograms we constructed. To illustrate a case synopsis, we provide an abbreviated synthesis of key points and a few observations from Grace’s case, an 82 year-old woman at the time of data collection who had been diagnosed with and treated for uterine cancer.

Grace has had a rough time. Husband is bed ridden and spent five months in a nursing home, just returning home recently. She had uterine cancer, was receiving treatment, then broke a bone, and spent five months in treatment and recovery, so couldn’t care for husband—he had to go to nursing home (“a place where people go to die”). One foot was amputated, so he wasn’t mobile and couldn’t be left alone. Grace has no children, her brothers live out of state, her 88-year-old aunt (like a sister) is in Ohio and her aunt’s husband is dying. Grace lives next door to husband’s cousin, they talk on phone, but he can’t do much for them. She relies on her “adopted” daughter—a woman who was interested in buying their land, but now just helps her out—buys her groceries and runs errands—her lifeline. Despite the fact that her blood family doesn’t live near her and they can’t visit, they are always on the phone, and that is so important to her. The woman from the cancer center who drove me out to her home (about 20 minutes away) loves Grace and said she has really been through a hard time. While I was there, an electrician was fixing her air conditioner, and she was very capably giving him instructions, and the man was very cordial and nice to her—they had a professional and caring interaction. She was wearing pajamas and a housecoat (it was 1:00 pm), and she said she never left the house. She said life was rough, but she kept going. She said she has “good genes.” She also had a lot of faith. Lived in the area for 14 years; born and raised in KY.

Initial Observations From This Case Study:

As a result of these strategies, we prepared an initial coding scheme that represented the first round of data reduction (i.e., open coding). We generated a long list of about 20 codes, organized by broader categories (e.g., diagnosis, active treatment, the discourse of survivorship) that included subcodes underneath each one. This initial scheme was still very close to the data in that we mostly utilized participants’ own words to indicate codes. On the coding scheme, if a code was a direct quote from a participant, we put quote marks around it. For example, if a woman had a very negative experience with her cancer treatment and had given up on receiving further treatment, we coded this type of text by using the woman’s own words: “I refuse to take more treatment; it beat me.” Additionally, after each coding category, we included “other” to locate topics not yet fitting into any of the previous codes. We continued to work with the data and in communication with one another to eliminate the “other” codes so that all data were accounted for. The following list is an example of how we organized codes around one main category: the diagnosis aspect of cancer:

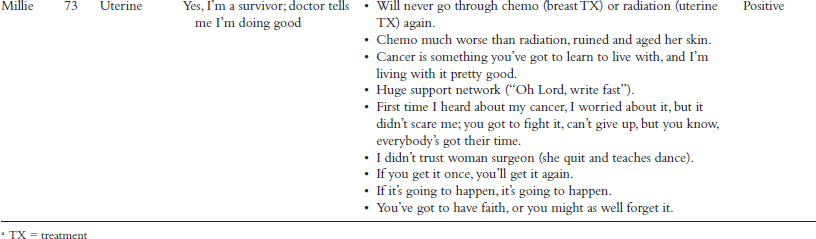

In the next phase of focused coding, we further reduced and synthesized our initial coding into the main topic areas of the cancer journey. To reach this point, we used the coding and analysis strategy of sorting thematic data into tables, accompanied by relevant participant demographic information. We used these data to help us organize and differentiate patterns among participant experiences. Table 5.1 illustrates this strategy. This table shows one participant per type, with her pseudonym, background information, various quotes from her transcript to support our coding decisions, and our analysis of her perceptions of post-treatment experience.

The final selective coding scheme, which consisted of two main themes, tells the story of the women’s cancer experiences. We utilized this final coding scheme as the outline for writing about the findings for our publication (Allen & Roberto, 2014). The first theme was labeled “From Symptoms to Diagnosis and Active Treatment” and included the four subthemes of (a) symptoms, (b) getting a diagnosis, (c) initial reactions to the cancer diagnosis, and (d) treatment and side effects. The second main theme was “Post-Treatment: Living with and Surviving Cancer.” In the final coding scheme, we also included the frequency counts (i.e., the number of cases exemplifying each type of experience) for each code. Table 5.2 shows the four types of living with and surviving cancer by frequency.

As we have chronicled previously, our collaboration began over 20 years ago, and has benefitted from our willingness to share resources and learn from one another. We practice equality in our work together and take responsibility for writing our papers, not leaving one of us in the lurch or expecting the first author of a paper to do most of the work. We also share the products and accomplishments of our work together. This equality is highly feminist, and reflects our commitment to feminist theory and praxis (Allen, 2016).

|

POSITIVE “Yes, I’m a cancer survivor” |

CAUTIOUS “Maybe, but I’m at risk for getting cancer again or I’m not cured yet” |

RESIGNED “I refuse to take more treatment” |

DISTANCED “I’m not a cancer victim; I do not identify with cancer at all” |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Abby |

Deborah |

Helen |

Lila |

|

Carla |

Edie |

Wilma |

Nora |

|

Fannie |

Julia |

Sadie |

|

|

Grace |

Thelma |

||

|

Iris |

|||

|

Kate |

|||

|

Millie |

|||

|

Olivia |

|||

|

Patsy |

|||

|

Rita |

|||

|

Violet |

|||

|

n = 11 |

n = 4 |

n = 2 |

n = 3 |

We do not underestimate the importance of trust in one another, in our data, and in the research process. Personal and professional trust is key to having a positive, collaborative working relationship with collaborators, participants, and gatekeepers. We have been upfront with each other about what we can do and cannot do on a project, especially if life intervenes and we are dealing with a family tragedy. When we first started working together, we frequently raised our voices and jumped out of our chairs, not in anger, but in excitement of developing and crystalizing the ah ha moments that occurred when in the midst of data analysis. Often working in Karen’s office, the graduate students next door worried and wondered why their professors were arguing. When they finally had the courage to ask us, we laughed as we explained that we indeed were yelling in disagreement but also in celebration of generating insights we were proud of!

To give an example of our differences, Katherine is much more open to using private experiences of grief and loss as a spring board to inform her research; Karen relies more on her observations of others and is much more open to using quantitative approaches in her research. As we have worked closely together over the last two decades, we have both expanded our ways of doing data analysis. Karen frequently takes the lead in qualitative analysis for some of her other research teams (e.g., Roberto, Blieszner, McCann, & McPherson, 2011), and Katherine now uses charts and tables routinely to structure and see patterns in her data, an approach she adopted from Karen.

We are similar in that we both are deeply committed to sharing our expertise with our students and helping them develop the methodological skills necessary to complete their graduate degrees. We share similar mentoring philosophies of high expectations of our students and intensive guidance and intellectual support as they pursue their own research. We consider the mentoring experience incomplete unless we include students on our own research and publish with them (Emma Potter in this case, who is contributing to three publications from this study), implementing the collaborative spirit with which we approach our own style with peers. That is, students publish with us (on projects we have conducted with each other, or with others), and we also give them opportunities to take the lead from our respective data sets. As feminist scholars, our goal is to coax our students toward becoming our peers by learning along with us.

Our struggles have not been in our research collaboration, but in finding the time to complete additional manuscripts and pursue external funding based on this data set. Our academic roles and responsibilities in teaching, mentoring, service, and in Karen’s case, administration, often require immediate attention and like for many others, the time that takes often comes from time allocated for writing. In many ways, we have been productive with several national and international presentations, two publications from the data set (Allen & Roberto, 2014; Potter, Allen, & Roberto, 2018), and more in the works. We are still mining the women’s data, and there are a host of issues to write about on the family members’ perspectives as well. So, a drawback of our otherwise productive collaboration is that when another project deemed more demanding comes up, we are amenable to postponing our own work until other big projects get off our desk. A benefit of writing this chapter is that it has spurred renewed effort to complete our other in-progress papers.

We often find that when we go to publish our work, however, reviewers are increasingly requiring the method to be described in a way that closely follows well-regarded texts outlining the gold standard of grounded theory procedures (Charmaz, 2006; Daly, 2007; LaRossa, 2005). As qualitative research methods become more standardized, we have encountered suspicion about our description of qualitative research as both reflexively intuitive (inductive) and conceptually/theoretically guided (deductive), because these approaches are often viewed in opposition to one another. It seems there is little room for overtly presenting the reflexive data analysis process of filtering through private experience and the occasional clash of perspectives and egos that go hand-in-hand with collaborative data analysis. Unfortunately, we have sometimes experienced that expectation as flattening out the dynamics of our data analysis process, thus leading to somewhat sanitized versions of how we have gone into the pit of emotionally and intellectually disagreeing, arguing, and often sharing from personal experience (e.g., the loss or frailty of our family members) that infuse our collaborative work. Again, writing this chapter together, which provided the freedom of transparency and disclosure, was a welcome and liberating experience, rare in academic work.

In this chapter, we have had the opportunity to depart from the textbook approach that students are now taught, and describe some of the behind the scenes messiness and passion in conducting qualitative data analysis. At the heart of all research is the knowledge and inspiration of the researcher. Although translating the dynamic process of data coding and analysis into publication may lose some of its spark, we, as researchers, must speak the language of our discipline and translate our work into words that others will be able to understand. The attention to the importance of family support and the fact that health and illness occur in familial and community contexts provided a common language to translate multiple perspectives on women’s cancer experiences into an account that is respectful of the women’s reflections and true to the actual steps we took to arrive at our interpretation and conclusions.

Allen, K. R. (2000). A conscious and inclusive family studies. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 4–17.

Allen, K. R. (2016). Feminist theory in family studies: History, biography, and critique. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 8, 207–224.

Allen, K. R., Blieszner, R., & Roberto, K. A. (2011). Perspectives on extended family and fictive kin in the later years: Strategies and meanings of kin reinterpretation. Journal of Family Issues, 32, 1156–1177.

Allen, K. R., Blieszner, R., Roberto, K. A., Farnsworth, E. B., & Wilcox, K. L. (1999). Older adults and their children: Family patterns of structural diversity. Family Relations, 48, 151–157.

Allen, K. R., & Roberto, K. A. (2014). Older women in Appalachia: Experiences with gynecological cancer. The Gerontologist, 54, 1024–1034.

American Cancer Society. (2017). Cancer facts and figures 2017. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society. Retrieved from www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2017/cancer-facts-and-figures-2017.pdf

Beesley, V. L., Janda, M., Eakin, E. G., Auster, J. F., Chambers, S. K., Aitken, J. F., Dunn, J., & Battistutta, D. (2010). Gynecological cancer survivors and community support services: Referral, awareness, utilization and satisfaction. Psycho-Oncology, 19, 54–61.

Behringer, B., Friedell, G. H., Dorgan, K. A., Hutson, S. P., Naney, C., Phillips, A., Krishnan, K., & Cantrell, E. S. (2007). Understanding the challenges of reducing cancer in Appalachia: Addressing a place-based health disparity population. California Journal of Health Promotion, 5, 40–49.

Bevans, M. F., & Sternberg, E. M. (2012). Caregiving burden, stress, and health effects among family caregivers of adult cancer patients. Journal of the American Medical Association, 307, 393–403.

Blumer, H. (1969). Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bogdan, R. C., & Biklen, S. K. (2007). Qualitative research for education: An introduction to theories and methods (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage.

Coyne, C. A., Demian-Popescu, C., & Friend, D. (2006, October). Social and cultural factors influencing health in Southern West Virginia: A qualitative study. Preventing Chronic Disease, 3(4), 1–8. Retrieved from www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1779288

Daly, K. J. (2007). Qualitative methods for family studies and human development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Duggleby, W. D., Penz, K., Leipert, B. D., Wilson, D. M., Goodridge, D., & Williams, A. (2011). “I am part of the community but …” The changing context of rural living for persons with advanced cancer and their families. Rural and Remote Health, 11. Retrieved from www.rrh.org.au/journal/article/1733

Elder, G. H., Jr., & Giele, J. Z. (Eds.). (2009). The craft of life course research. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Gilgun, J. F. (2016, November). Deductive qualitative analysis and the search for black swans. Paper presented at the Theory Construction and Research Methodology Workshop, National Council on Family Relations, Minneapolis, MN.

Goldberg, A. G., & Allen, K. R. (2015). Communicating qualitative research: Some practical guideposts for scholars. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77, 3–22.

LaRossa, R. (2005). Grounded theory methods and qualitative research. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 837–857.

Lyttle, N. L., & Stadelman, K. (2006). Assessing awareness and knowledge of breast and cervical cancer among Appalachian women. Preventing Chronic Disease, 3(4), 1–9. Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2006/oct/06_0031.htm

McGoldrick, M., Gerson, R., & Petry, S. (2008). Genograms: Assessment and intervention (3rd ed.). New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Potter, E. C., Allen, K. R., & Roberto, K. A. (2018). Agency and fatalism in older Appalachian women’s cancer-related-information seeking. Journal of Women & Aging. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/08952841.2018.1434951

Richardson, L. (1997). Fields of play: Constructing an academic life. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Roberto, K. A., Allen, K. R., & Blieszner, R. (2001). Older adults’ preferences for future care: Formal plans and family support. Applied Developmental Sciences, 5, 112–120.

Roberto, K. A., Blieszner, R., McCann, B. R., & McPherson, M. C. (2011). Family triad perceptions of mild cognitive impairment. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 66B, 756–768.

Schlegel, R. J., Talley, A. E., Molix, L. A., & Bettencourt, B. A. (2009). Rural breast cancer patients, coping and depressive symptoms: A prospective comparison study. Psychology and Health, 24, 933–948.

Schoenberg, N. E., Hatcher, J., Dignan, M. B., Shelton, B., Wright, S., & Dollarhide, K. F. (2009). Faith Moves Mountains: An Appalachian cervical cancer prevention program. American Journal of Health Behavior, 33, 627–638.

Schoenberg, N. E., Miller, E. A., & Pruchno, R. (2011). The qualitative portfolio at The Gerontologist: Strong and getting stronger. The Gerontologist, 51, 281–284.

Smith, D. E. (1993). The Standard North American Family: SNAF as an ideological code. Journal of Family Issues, 14, 50–65.

Sprague, J. (2005). Feminist methodologies for critical researchers: Bridging differences. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

Wilson, R. J., Ryerson, A. B., Singh, S. D., & King, J. B. (2016). Cancer incidence in Appalachia, 2004–2011. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers, 25, 250–258.