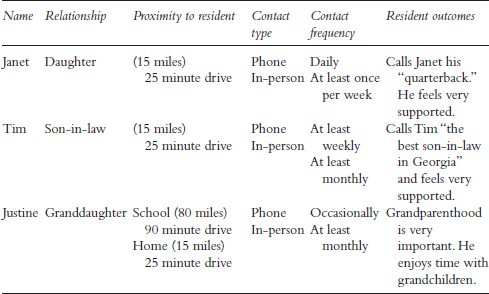

Table 11.1 Resident/Convoy Profile Table: “Mr. Story’s” Informal Convoy

With an emphasis on meaning, experience, as well as contradictions and tensions in everyday life, qualitative research has much to contribute to the understanding of relationships, including complex and dynamic social processes such as those found in social, family, and care networks. Research that captures and reflects the nuances of family life demands approaches to data collection and analysis that are as complex, fluid, and dynamic as the experiences and relationships they purport to understand. Such approaches are time-consuming, costly, logistically challenging, and rare (Kemp et al., 2017). Moreover, when they are used, it is not common for researchers to share detailed insight into their analytic procedures. Our goal in this chapter is to do just that, providing an in-depth account of the methods used to analyze data from the longitudinal qualitative study, “Convoys of Care: Developing Collaborative Care Partnerships in Assisted Living” (hereafter the Convoy Study).

This study was guided by our Convoys of Care model (Kemp, Ball, & Perkins, 2013), which was developed based on a synthesis of theoretical and empirical data, including our own grounded theory research set in assisted living and involving older adults, their family members and friends, and care workers. Care convoys are:

the evolving collection of individuals who may or may not have close personal connections to the [care] recipient or to one another, but who provide care including help with activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), socio-emotional care, skilled health care, monitoring, and advocacy.

(Kemp et al., 2013, p. 18)

The overall goal was to learn how to support informal care (unpaid care by family and friends) and care convoys in assisted living in ways that promote residents’ abilities to age in place with optimal resident and caregiver (both paid and unpaid) quality of life.

An in-depth consideration of the study’s design and methods appears elsewhere (see Kemp et al., 2017). Briefly, data collection methods consisted of in-depth and informal interviews, participant observation, and review of assisted living community and resident records. We collected data in eight assisted living communities that varied by size, location, resident characteristics, ownership, and resources—variables research suggests likely influence care experiences. We followed a sample of residents and their informal and formal caregivers over a two-year period, attempting at least weekly contact with residents and twice-monthly contact with convoy members. Data collection was organized in two separate stand-alone waves, each involving four sites, studied for two years. Our sequential design, motivated by analytic considerations, enhanced cumulative knowledge building regarding variables of interest and allowed us to make informed adjustments regarding data collection and analysis procedures over the five-year period. Here, we describe the data analysis for a recently published paper (Kemp et al., 2018), which generated a theory of how care network members navigate the care landscape.

Unlike most studies on families, social relationships, and care, ours endeavored to study entire networks rather than individuals or dyads (but see Bengtson, Biblarz, & Roberts, 2002; Connidis & Kemp, 2008). We aimed to recruit residents’ complete care networks, including multiple informal members. Adult children were the most common informal caregiver, but grandchildren, siblings, extended family, and friends also participated. Formal caregivers included assisted living administrators and staff and external care workers, such as hospice personnel, physicians, and home health professionals.

During Wave 1, from 2013 to 2015, we collected longitudinal data on 28 residents and their entire care networks. We conducted formal interviews, digitally recorded and transcribed, with 28 residents and 114 caregivers. Data collection also included participant observation, including ongoing informal interviewing and resident record review. We logged 2,225 observation hours in 809 visits to study sites; observations and informal conversations were recorded in fieldnotes. Begun in 2016, Wave 2 was incomplete when this chapter was written; these data are not included here. We anticipate a final sample of 50 residents and 225 formal and informal caregivers across the eight diverse settings (see Kemp et al., 2017). Collecting and making sense of these data requires time, patience, and a systematic and rigorous, yet flexible approach, such as that offered by grounded theory methods.

Although there are numerous approaches to qualitative data collection and analysis, we have found that our research questions and topics are best suited to a grounded theory approach (Corbin & Strauss, 2015). We endeavor to develop knowledge cumulatively, and our most recent research builds upon our past work—much of which focused on understanding the processes of social and care relationships and networks. We also recognize the need to adopt research strategies that can be modified as needed to suit project needs and address our research goals.

Our approach to grounded theory highlights the interrelationship of data collection and analysis. These activities are performed simultaneously and iteratively and inform one another throughout the research process. Thus, our analysis began at the start of data collection.

As outlined, the Convoy Study was large, complex, and longitudinal, involving multiple data collection techniques at multiple sites and an evolving collection of participants and researchers. It called for procedures that simultaneously helped us organize and analyze vast amounts and sources of data. We started with foundational analytic strategies that provided the scaffolding for more advanced, targeted analysis. The targeted analysis addressed specific research questions, involved higher-level analysis, and generated conceptual models and theory.

Foundational analytic activities were developed, refined, and carried out as part of the interplay of data collection and analysis. They included team meetings, ongoing data analysis and management (e.g., transcript and fieldnote review, data entry, and coding), development of site and resident/convoy profiles, and memoing. Our longitudinal study design required maintaining a large, dynamic research team (13 members on average), forming a convoy of researchers comprised of faculty, staff, and graduate students from diverse academic and social backgrounds. Although we had team transitions over the study course, we maintained a stable core at each site, enabling consistency in data quality and analysis (Kemp et al., 2017).

Twice-monthly meetings with the entire research team led by Kemp, the principal investigator, provided an important forum for discussing data collection and analysis activities, including new lines of inquiry, fieldwork challenges, data gaps, sampling strategies, and discussions concerning similarities and differences across sites, residents, and time. Although agenda items varied, each meeting included site updates regarding research aims and ongoing analysis. We recorded team discussions in Microsoft Word documents, which became part of our qualitative database and subject to analysis.

Team meetings led to pivotal decisions throughout the study, especially early on. For example, initially, and as noted elsewhere (Kemp et al., 2017), we relied on residents to identify convoy members but discovered this approach led to the inclusion of individuals who contributed little, if anything, to care and the exclusion of active contributors. Based on ongoing dialogue and considerations of care convoys and relationships, we amended our definition of convoy members to be those we identified through our data as ongoing or periodic participants in resident support over the two years. We deemed it necessary to: “capture instances where networks were dense, but now are not (and why);” investigate “differences based on the assisted living community’s connection to larger surrounding community;” “note people” who normatively would be expected “to be in a convoy” (e.g., children), “but who were not active convoy participants;” and “capture (and examine) positive and not-so-positive relationships” (meeting notes, October 16, 2014).

Throughout the study we shared fieldnotes and interview transcripts, noting theoretical, methodological, and operational implications in memos (see the section on “Memoing”) and team discussions. These practices allowed informed adjustments in the field and helped guide analysis. For instance, in Wave 2 we instituted a fieldnote template that included a table with a drop-down menu to track residents’ health and convoy transitions, key foci of analysis. We stored all data and study files on a secure password-protected shared drive maintained by Georgia State University and only accessible to active team members. Files could be accessed by all, but only edited by one researcher at a time.

We used multiple databases and programs to store, manage, and analyze data (Kemp et al., 2017). IBM SPSS21 databases recorded site features (e.g., size, ownership, fees) and participants’ social, demographic, and health characteristics. We maintained four SPSS databases for (a) sites, (b) residents, (c) informal caregivers, and (d) formal caregivers. These data helped characterize sites and participants, individually and in the aggregate, and aided in identifying and interpreting similarities and differences across sites and participants, discovered through qualitative analysis. For example, aggregate facility data regarding residents’ functional status and staffing levels helped explain variations in convoy structure and function.

Although we retained paper files of interview transcripts and fieldnotes (created in Word) in three-ring binders for each site, we housed digital qualitative data in NVivo10 software, later NVivo11, for subsequent coding and analyses. We created and maintained separate NVivo projects for each of the eight research sites and for meeting notes. The site projects varied based on resident census, but each contained between 16 to 52 interviews and 87 to 371 fieldnotes. These projects could have been merged, but the smaller project files were easier to manage and less prone to instability. The team coded data directly in NVivo.

Coding is an essential activity in qualitative analysis and a way to categorize data (Maxwell & Chmiel, 2014). At the study’s outset, as recommended by Lofland, Snow, Anderson, and Lofland (2006, p. 205), the team developed a set of basic, yet comprehensive, “folk/setting-specific” codes guided by observations in the field, research aims, and existing theory and research. These codes allowed us to tag, sort, and organize large chunks of data for higher-level analysis. We applied these broad codes to relevant words and phrases identified through line-by-line coding.

Given the volume of data, folk/setting-specific coding facilitated sorting the data into large, yet manageable, segments of broad categories captured by using 14 “parent” nodes, with varying numbers of “child” nodes (these terms represent NVivo’s code hierarchy and terminology). For instance, and shown in Figure 11.1, the higher-order parent node “care needs and activities” was associated with eight child nodes delineating types of care, such as “medical” and “socioemotional.” Nodes also captured multi-level factors (e.g., resident/caregiver, facility, cultural, community) expected to influence care processes, interactions, transitions, experiences, and outcomes. We created name codes for residents and staff in each setting, allowing easy retrieval and review of data associated with these residents and their convoys. For flexibility, we also designated a “to be coded” code for data that needed future coding, possibly with a new or refined code, which required group discussion before coding.

Team members received NVivo training, which consisted of an introduction to the program and coding features and culminated in homework assignments used to compare coders by using NVivo’s coding comparison function with the goal of achieving near perfect inter-coder reliability (see Figure 11.2). We had ongoing discussions in team meetings and smaller groups, all recorded in notes, to establish the utility of codes and advance code definitions, and we also kept a Word document on our shared drive with current codes and definitions. Joy, our project manager, observed in a memo,

I think it has been effective for the team to meet and talk about coding. The graduate assistants who have participated more in these conversations code more quickly than those who do not, and seemed to have gained analytical skills based on insights they offer individually and in team meetings.

(October 4, 2017)

Our strategy for documenting and analyzing residents’ convoy and health changes evolved over the study. In both waves we documented these changes in fieldnotes. In Wave 1 we recorded these data in a Microsoft Access database, a strategy we abandoned for a more nimble, manageable, and straightforward Microsoft Excel database in Wave 2 (see Figure 11.3). Reflecting on our decision, Joy explained:

We do not have enough participants to require such a complex database. Because the reporting tools are not as fluid as what we need to meet our needs, we end up doing most reporting in Excel, exporting data from Access.

(November 5, 2015)

Convoy and health changes also were recorded in both waves through profile writing, which was a central component of our analytic strategy.

We developed profiles for all eight sites and all 50 resident/convoys, which allowed in-depth, systematic study of individuals, networks, and settings and also facilitated constant comparison, an essential grounded theory activity (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). We created profile templates informed by the Convoys of Care Model (Kemp et al., 2013), our research aims and questions, and observations in the field. Site profiles described each setting, documenting size, location, history, ownership, staffing levels, care culture, policies, and practices and indicating local and wider community factors influencing care experiences and convoys.

Resident profiles contained details about: personal and health history; care needs; daily life; health transitions; convoy size, composition, activities, collaboration, and transitions; key factors; outcomes; and lessons learned. Profiles also included convoy tables (see Table 11.1), which identified members and their relationships, and diagrams representing residents’ self-care activities and care contributions and connections of their informal and formal convoy members. We modified the diagrams to represent health and convoy changes over time. Initially, for example, Alice provided some self-care and her convoy was comprised mostly of staff and family (Figure 11.4). As she declined, her self-care decreased and the number and types of care providers expanded (Figure 11.5). Additionally, as data collection and analysis proceeded, we augmented resident profiles with examples from interview, fieldnotes, and record review data, including passages from resident or caregiver interviews that spoke to the care network and attitudes about receiving and giving care. In Wave 1, we made these additions retrospectively, often during coding. During Wave 2, which is ongoing, we are prospectively enhancing profiles, a technique that is less laborious and strengthens the connection between data collection and analysis. These profiles provide fundamental material for more targeted analyses.

Memoing is an important tool used by qualitative researchers that provides an ongoing way for team members to document and share thoughts on methods and analysis (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). We recorded “operational” memos to track problems and successes, procedural changes, and issues regarding relationships with participants. We used “theoretical” notes containing ideas about sampling and insights, observations, interpretations, and questions about the data to reflect on the analysis process and facilitate learning more about a topic’s salience. For instance, after a conversation with a resident’s daughter about the role church members played in informing her about her father’s activity, our project manager reflected, “This shows the importance of informal caregivers supporting one another, as well as residents. I wonder if we see stronger support in convoys where there is involvement in a church or other organized religious or community group” (November 4, 2015). And, after a field visit Mary mused, “It will be interesting to see if Jan’s son takes her to the neurologist. This is definitely an example of a convoy with no externally provided health care. This arrangement may not be in the resident’s best interest” (March 4, 2015).

Most memoing activities were built into our procedures and researcher initiated in that individuals recorded their thoughts as they collected and analyzed data. Fieldnotes contained the heading “MEMO” at the end of the document allowing researchers to share ideas about ongoing processes and emerging insights. As part of each fieldnote, these memos were coded within NVivo under the parent node, “Research” with child nodes “operational” and “theoretical.”

Early fieldnote memos largely concerned theoretical sampling, fitting into the setting, researcher-participant relationships, and reflections on the effectiveness of data collection procedures but also contained insights into sampling and data interpretation. Our reflections grew in sophistication and complexity as our knowledge and understanding increased. For example, in the first months of data collection while seeking maximum variation (Patton, 2015) based on resident and family characteristics, Molly noted in one memo, “Although Jenna tends to repeat herself, I think she would be an excellent resident participant. A care worker indicated that her family is somewhat dysfunctional and her primary caregiver is an aunt by marriage” (January 5, 2014). Memos also contained reflections on patterns and connections with existing literature. Candace noted after a Garden House visit (October 12, 2014), “Frank brings to mind some of the women in Mary’s book, Surviving Dependence (Ball & Whittington, 1995) in terms of his ability to get people to do things for him. It is very interesting that his daughter disapproves… ”

Alongside memoing within fieldnotes, located within the NVivo project files, each researcher created a personal memo in a Word document housed on our shared computer drive, located outside NVivo. In these additional memos, researchers recorded ongoing thoughts on data collection and analysis, including their feelings, connections between data and the literature, and avenues for further exploration. Personal memos will be moved into NVivo when data collection ends.

Researchers routinely added to their personal memo documents during NVivo coding sessions, and memoing was discussed informally and during team meetings. Meeting notes (January 20, 2016) recorded the following:

Liz shared some thoughts she has been memoing about. She was coding Andrea’s fieldnotes and she had a note about what is expected of males versus females when it comes to caregiving. She also discussed that there are contradicting stories at times between a resident and a caregiver. We seem to get multiple perspectives on things that happen that do not always align. Such reflections encouraged researcher discussions.

Candace encouraged the team to examine contradictory accounts within the data, including participant accounts. We embraced the notion that not all information would align, which in and of itself, was a key study contribution (Kemp et al., 2017). Some data were clearly conflicting; others were more nuanced. Candace hypothesized, for instance:

The different views Catherine and Alice gave me about Jack [resident] emphasize the value and potential challenge of including multiple viewpoints. At first, their versions seemed in conflict, but upon reflection, it is possible they were addressing different dimensions of his well-being. Catherine is more apt to talk to him about his health care and conditions—his care needs, including the help he receives and his meds… . In contrast, not that Alice is unaware of his health and care, her interactions are more about keeping him mentally stimulated and socially engaged.

(April 30, 2015)

Memos guided cumulative knowledge building by informing and advancing questioning of participants, settings, and data. As analysis progressed, we sharpened our focus on key patterns and concepts we were identifying. Memoing, for both foundational and targeted analysis, was key throughout the research process.

The foundational analytic strategies described previously provided systematic methods to organize vast amounts of data, thereby setting the stage for higher-level analyses. Many of our targeted analytic activities were ongoing while writing this chapter and form the basis of publications in preparation. Throughout the project we maintained an “Analysis and Working Documents” folder to house all analytic files (e.g., reports and analysis charts in Word) organized by topic; within topics, subfolders contained analysis pertaining to each research site.

Ongoing analysis involved all researchers and was discussed in biweekly team meetings and recorded in Word as team meeting notes. The research team also organized into smaller teams that conducted more targeted analysis based on our research aims and ongoing analysis. Each team was led by different senior investigators and included Candace, the principal investigator. We maintained a Word document with the table, “Convoy Analysis Planning and Dissemination” to record targeted analysis. Columns included: analysis focus, analysis activities and goals, progress toward goals, and team leads and supports. We organized this information by analysis stage: (a) presented at conferences and manuscript in process; (b) to be presented, analysis needs advancing, and manuscript preparation; and (c) preliminary thinking phase.

For present purposes, we offer an in-depth description of one targeted analysis using Wave 1 data that we report in an article we refer to as the patterns paper (Kemp et al., 2018). Briefly, our aims of that analysis were to learn how residents’ care convoys are structured and function and how and why they vary. Through this targeted analysis, we developed a typology of residents’ care convoys and developed a conceptual model and a core process we labeled “maneuvering together, apart, and at odds.” The model outlines various ways and factors that influence how residents and care network members negotiated care in assisted living across time. Next, we describe how we arrived at these conclusions.

Our coding activities drew on our basic codes (described previously) and accompanying NVivo node reports most germane to understanding care network patterns. We ran node reports for “convoy properties,” “influential factors,” and “care activities, needs, and interactions,” to access data describing the structure, function, and sources of variability of convoys, and examined resident/convoy profiles. Using these data, we followed the three-stage coding procedures outlined by Corbin and Strauss (2015), which involves open, axial, and selective coding. Through open coding, we inspected these data for concepts based on our questions about convoy patterns. Open coding can be accomplished multiple ways, including applying codes line by line and to a sentence, paragraph, or entire document (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). We used all of these units, but mostly coded sentences and paragraphs connected to individuals, convoys, and sites.

We applied initial codes to all data that provided insights into how convoys were structured (e.g., “primary informal caregiver” and “shared responsibility”) and operated (e.g., “collaboration,” “leadership,” “consensus,” “proactive,” and “reactive”). Our coding was guided by sensitizing concepts from the literature, including our own past work, and by new patterns we observed in the data. For instance, both past work (Ball et al., 2005) and current data chronicle the existence of “primary” and “shared” roles among informal caregivers in support of assisted living residents. Using an inductive approach, we expanded these concepts and identified variations within these structures.

Early in our targeted analysis, we used Word to create analysis charts using the “Table” feature. Word permitted the flexibility to provide detailed information and insights beyond what was capable in the NVivo program. Our profiles informed the creation of charts and were fundamental to coding and analytic processes. The charts enabled us to compare and contrast convoys within and across study sites and over time and facilitated the identification of similarities and differences.

Each research site team was tasked with developing analysis charts focused on resident convoys from their respective sites. Our targeted coding and chart-making activities were based on “the use of questioning” (Strauss & Corbin, 1998, p. 89). In our first round of charts, we asked the data: How are residents involved in their own care and what are their needs? Who else is involved in residents’ care? What do they do? How often, when, and where? Is there collaboration among caregivers? What, if any, changes have occurred to resident health and convoy structure and function?

Begun early in 2015, these charts evolved over time, building cumulatively on previous versions with our lines of questioning derived from data in previous charts. Tables 11.2 to 11.4 illustrate the progression of charts from early drafts focusing on the structure and function of each resident’s informal and formal networks to a final version summarizing individual convoys. These initial charts provided a way of sorting convoys based on structure (primary informal caregiver and shared informal responsibilities) and function (what support was provided by whom and under what circumstances) and ultimately facilitated axial coding (Corbin & Strauss, 2015), through which we related initial and other categories to each other. In these more sophisticated charts (Table 11.5), we separated resident convoys according to the structure of their informal networks. At this stage, we asked the following questions of the data: What are the primary resident, informal caregiver, assisted living setting, and community factors that influence care experiences and outcomes? What, if any, convoy collaboration occurs? What are the outcomes for residents, informal caregivers, and the care setting? Based on these tables, we noticed the centrality of collaboration, communication, and consensus, the basis for our convoy typology.

The specific categories (“cohesive,” “fragmented,” and “discordant”) associated with our typology (Kemp et al., 2018) were developed cumulatively and iteratively over a three-month period of reviewing analysis charts and profiles, memoing, and discussion. Over the years, our analytic discussions have taken place individually and collectively in conference rooms, offices, homes, and over meals, tea, and wine, during swims and hikes, and while traveling. Venue changes facilitated the creative process, but also broadened the time we spent on analysis. And, our extracurricular activities were essential distractions when analysis became overwhelming.

Among the many lessons learned, we can confidently say that rigorous analysis that does justice to the data cannot be done quickly or be forced, but also that clarity sometimes comes outside of the office. For instance, our typology labels were drafted on a notepad during a brainstorming session while two investigators, Candace and Mary, were traveling by car, discussed at great length, and applied to a sampling of the data.

During the ensuing full-team meeting, Candace presented the typology and analysis charts and asked researchers to evaluate whether the categories were universally compatible with the data and exhaustive. Through negative case analysis (Corbin & Strauss, 2015) we sought out cases that did not fit our theorizing. All Wave 1 convoys fit the typology, but we engaged in considerable discussion about the static nature of a typology, opting to conceptualize categories as fluid instead. For example, although most convoys were “cohesive,” at times they contained elements associated with “fragmented” or “discordant” convoys. It was important to note these non-cohesive elements and understand how, why, and with what outcomes change happened. Thus, we refined our typology to account for the fluidity of categories.

|

Resident |

Informal leadership type/ division of responsibility (structure) |

Resident care needs and informal roles (function) |

Resident, informal, formal outcomes (adequacy/outcome) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Ted Cohesive Convoy |

One primary person (friend) in charge; she has some support from her husband. Communication is good among caregivers. |

Resident has moderate ADL need and minimal IADL need. He can toilet himself and participate in management and finances. His friend handles all IADL and provides socioemotional support and some management. Facility staff handle needed ADL care. Health Care received on site. |

Resident’s needs are met and feels supported; caregivers do not feel burdened. Ted wishes he could see his daughters more. |

|

Debbie Discordant and Fragmented Convoy |

Convoy is made up of 2 sisters, 3 children, and boyfriend. Convoy has no real leadership. Minimal communication and collaboration among family members and between the children and staff. No concerted effort. Some conflict exists among family. Children unresponsive to staff requests. |

Debbie has Alzheimer’s disease and virtually no role in her care. One sister manages financial affairs, with help from the other. The sisters and facility push Debbie’s children to assume more responsibility with limited success. Her sisters, boyfriend, and son try to provide socioemotional support. Staff manage care and provide some socioemotional support. Her parents never visit. |

Debbie is frequently bored and would like to see her family and boyfriend more. Her sisters find caring for her stressful because of work and health problems and Debbie’s condition; the children are distressed about her condition and have limited time to help. Debbie is discharged because of behavior issues related to dementia; this outcome might have been avoided with a more cohesive convoy. |

Identifying our typology based on Wave 1 data was accomplished during nearly three years of data collection and analysis. Yet, the overarching story line (LaRossa, 2005) required further analysis and an additional three months. By looking at similarities within and across convoys and noting the experiences of and language used by key convoy members, through selective coding (Corbin & Strauss, 2015) we refined and integrated our concepts into a conceptual framework organized around our core category, “maneuvering together, apart, and at odds” (Kemp et al., 2018). This category was central to all the concepts identified in our analysis and offers a theory explaining how convoys negotiate the assisted living terrain.

Evoking images of navigation found in our data, our core category linked subcategories in our explanatory scheme to characterize the dynamic and variable patterns and processes associated with residents’ care in assisted living. Our analysis showed that the care landscape was marked by continuity and change, predictable and unpredictable, requiring convoy members to negotiate care in an ongoing way. Yet each resident, convoy member, and, by extension, entire convoy acted under variable circumstances with a range of outcomes for residents’ quality of care and life and ability to age in place, and their caregivers’ quality of life.

Diagraming relationships among categories, concepts, and contexts was a major part of the final stage of our selective coding analysis (Corbin & Strauss, 2015). While attempting to finalize the story line for this analysis and identify the relationship among concepts and categories and integrate our findings, Candace began sketching a conceptual model by hand on notepads, recycled paper, her office whiteboard, and even on napkins and envelopes. Figure 11.6 is an example of these early drawings, which were eventually refined using Word’s drawing canvas and tools (Figure 11.7). Candace solicited feedback in team meetings that helped finalize the core category and conceptual model. Email correspondence from Molly to Candace (February 7, 2017) on a later version of the conceptual model offered the following observations:

In contrast to Jen, the non-circular format of “Maneuvering Together, Apart, and at Odds” does not bother me. I agree with Jen that you need some element of time. What about pulling out “Resident Stability and Change” and making “Stability and Change” a stronger concept in your model? I think we saw stability and change in convoy members both formal and informal. We saw it in facility culture, etc. That might give you your time concept i.e., if you do not limit it to the one box and just to residents.

In addition to showing how collaboration occurs, this communication hints that multiple, sometimes competing viewpoints occur within research teams and, hence, can create challenges. Much like the contradictory accounts within our data, we felt that differences of opinion within the team reflected reality and embraced them as part of the research process. Regular meetings and ongoing communication, including listening, were important team-building exercises (Hall, Long, Bermbach, Jordan, & Patterson, 2005) throughout data collection and analysis. Our project manager memoed that investigators fostered an environment where all members felt “comfortable sharing their analytic and strategic ideas, which results in better results for everyone” (October 9, 2015). Ongoing group thought and collaboration were essential to developing an in-depth and complex understanding of themes and patterns that crosscut settings, participants, and convoys.

In teaching qualitative analysis, Candace uses an illustration of a magician pulling a rabbit out of a hat to introduce the fallacy of themes emerging quickly and easily from the data. In the end, as this chapter and others show, qualitative analysis, when done well, is enormously laborious. There are no shortcuts or quick approaches to quality analysis. Our colleague Patrick Doyle noted in a personal communication, “You have to dive deep to see what’s on the other side before you can really understand.” We wholeheartedly agree and acknowledge that there are multiple ways to dive deep. We hope that by sharing our ways, others can learn from our experiences, adopt or modify what makes sense, and ultimately develop optimal strategies for conducting qualitative analysis tailored to specific projects.

Work reported in this chapter was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01AG044368). Contents are the authors’ responsibility and do not necessarily represent the views of the NIH. We are grateful to all those who participated in the study and to our convoy of researchers, including Joy Dillard, Elisabeth Burgess, Jennifer Craft Morgan, Patrick Doyle, Carole Hollingsworth, Elizabeth Avent, Victoria Helmly, Andrea Fitzroy, Russell Spornberger, and Debby Yoder.

Ball, M. M., Perkins, M. M., Whittington, F. J., Hollingsworth, C., King, S. V., & Combs, B. L. (2005). Communities of care: Assisted living for African American elders. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Ball, M. M., & Whittington, F. J. (1995). Surviving dependence: Voices of African American elders. New York, NY: Routledge.

Bengtson, V. L., Biblarz, T. J., & Roberts, R. E. L. (2002). How families still matter: A longitudinal study of youth in two generations. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Connidis, I. A., & Kemp, C. L. (2008). Negotiating actual and anticipated parental support: Multiple sibling voices in three-generation families. Journal of Aging Studies, 22, 229–238.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hall, W. A., Long, B., Bermbach, N., Jordan, S., & Patterson, K. (2005). Qualitative teamwork issues and strategies: Coordination through mutual adjustment. Qualitative Health Research, 15, 394–410.

Kemp, C. L., Ball, M. M., Morgan, J. C., Doyle, P. J., Burgess, E. O., Dillard, J. A., … Perkins, M. M. (2017). Exposing the backstage: Critical reflections on a longitudinal qualitative study of residents’ care networks in assisted living. Qualitative Health Research, 27, 1190–1202.

Kemp, C. L., Ball, M. M., Morgan, J. C., Doyle, P. J., Burgess, E. O., & Perkins, M. M. (2018). Maneuvering together, apart, and at odds: Residents’ care convoys in assisted living. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B, 73, e13–e23. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbx184

Kemp, C. L., Ball, M. M., & Perkins, M. M. (2013). Convoys of care: Theorizing intersections of formal and informal care. Journal of Aging Studies, 27, 15–29.

LaRossa, R. (2005). Grounded theory methods and qualitative family research. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 837–857.

Lofland, J., Snow, D., Anderson, L., & Lofland, L. H. (2006). Analyzing social settings: A guide to qualitative observation and analysis (4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Maxwell, J. A., & Chmiel, M. (2014). Notes towards a theory of qualitative data analysis. In U. Flick (Ed.), The Sage handbook of qualitative data analysis (pp. 21–34). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative methods and evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. M. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Sage.