BLACKBERRY FLOWER

The following is a brief overview of many of the wonderful, delicious wild foods that can be foraged here in the Pacific Northwest. From berries, greens, and mushrooms to seaweed, shellfish, and crustaceans, there are so many products that you can discover. You can start in your own backyard but the best products will be found on a trip to the wild areas of our region.

BLACKBERRY FLOWER

Berries literally are the low-hanging fruit. Start here and you will immediately feel like a master forager. If you live in the Pacific Northwest, chances are you have picked berries at some point. They are a truly abundant product of our fields, forests, and shores. Whether you were a child with berry juice smearing your face, happily plucking them off the bushes, or an adult filling an ice cream bucket with delicious nuggets, most of us have already experienced the delicious world of foraging. You can think of this as a gateway to the wonderful world of edible wild plants.

Berries are everywhere. They are part of the reproductive process of plants and an important food for our wildlife. Blackberries are sometimes so abundant they press against the edges of civilization, weaving through abandoned cars and twisting through the fences, straining to expand and capture more sunlight and nutrients. You get the feeling if we were to let down our guard, blackberries would eventually take over everything we have carved out in civilization.

One of the best producers of fruit is Himalayan Blackberry. It actually sprung from the soils of Armenia and Iran. This robust plant has aggressively expanded to many corners of the planet and produces copious amounts of sweet berries. It was introduced to North America about 130 years ago and now dominates the landscape of the Pacific Northwest. Like many other foraged plants, it is an invasive species with benefits. If you can’t find the Himalayan Blackberry, you are probably not trying.

RASPBERRY

You tend to notice the blackberries first with their voracious growth, sweet berries, and large thorns, but if you look closely you will also find huckleberries, blueberries, wild strawberries, and many other wonderful finds. On my farm, I can’t walk 10 feet without coming across three or four types of edible berries. They are nature’s alluring bait, built to entice animals and birds to eat them and transport the seeds to new locations. This is one reason berries travel far and wide.

There are poisonous berries throughout the region. Many are bitter or strangely coloured (pure white for example). Correct identification is important for any wild foods you are going to consume. But you could easily stick with the basic blackberries, blueberries, huckleberries, and salal berries and have excellent success foraging.

Blackberry (Rubus spp.) There are almost 400 species of blackberry that appear all over the planet. Our Pacific Northwest native variety is the trailing blackberry (R. ursinus). The plant favours the edges of forests and paths and fruits the earliest of the blackberries. The fruit is tiny, sweet, and very aromatic. It is perhaps the tastiest of the blackberries but takes a lot of work to pick any quantity. Look for the trailing berry on the ground, sometimes in large masses near the edge of forests. The leaves are small and pointed with a wrinkled appearance in the centre (along vein lines) and a fine-toothed edge.

The Himalayan Blackberry (R. armeniacus) is an aggressive, introduced species that readily adapts to all kinds of urban and rural environments. The plant grows in dense patches and tends to fruit berries in the thousands. The plant will also use nearby trees to gain access to sunlight and nutrients. The Himalayan Blackberry fruits in late July and sometimes continues fruiting into the late fall. It is distinguished by its impressive mass (canes can grow up to 30-feet [9 m] long) and oval leaves with a toothed edge.

The third major type of blackberry is the Cutleaf Evergreen Blackberry (R. laciniatus). This is an escapee from commercial cultivation and creates berries that fruit a little later in the year (late summer to fall). It is distinguished by its deeply cut leaves and dense fruit. It is a much smaller plant than the Himalayan Blackberry and tends to grow in circular clumps. The skins are a little firmer than the Himalayan berries and produce a fine and delicate flavour.

A. SALAL BERRIES B. BLUEBERRIES C. SALMONBERRY

Blueberry (Vaccinium spp.) Having grown up in Nova Scotia, I have special ties to blueberry picking. Luckily, the Pacific Northwest is also an abundant habitat for these berries. It is possible to pick buckets full of wild blueberries, which have a superior flavour over the larger commercial varieties. There are several closely related species of blueberries and huckleberries that often grow under the same conditions. You could easily mix up the different species on the same foraging expedition. It doesn’t really matter; they are all delicious and choice fruits. Blueberries are high in antioxidants and make great desserts, jellies, jams, vinegars, wines, and infusions.

Blueberries freeze very well and take little effort to clean and process. No wonder they are a favourite fruit of both bears and humans. A common coastal variety, V. ovalifolium, has smooth oval-shaped leaves, white flowers, and grows in bushes up to 5-feet (1.5 m) tall.

Oregon Grape (Mahonia repens or M. aquifolium) These beautiful green plants resemble holly and have a sharp, wavy edge that can scrape and cut flesh if you brush by it. There are at least two species that appear in our region, one is a low-level bush (M. repens) and the other (M. aquifolium) is a taller bush that reaches 3 feet (1 m) in size.

The leaves often blush reddish around the edges in late fall. In the spring, a yellow flower cluster emerges that is edible with a nice citric acidity. The green berries are good when pickled or made into forest capers. In fall, the berry clusters redden and eventually turn a deep purple with a whitish frosting on the surface. If left on the plant, the berries will shrivel like raisins.

The berries make an excellent jelly if harvested before the first frost. They have an excellent proportion of pectin. After a frost, they are sweeter but the pectin levels are reduced; I make these berries into syrup or infuse them in cider vinegar. The Oregon grape is considered to contain very high levels of phytonutrients (such as antioxidants) and is an excellent source of vitamin C.

Red Huckleberry (Vaccinium parvifolium) This plant is a beautiful ornamental as well as a provider of delicious berries. The red huckleberry is distinguished by its small teardrop leaves and elegant structure, kind of like a natural form of bonsai. The shrub is very common and in good years is loaded with so many berries that the branches dip toward the ground.

The taste is tart and sweet, similar to a red currant. The berries freeze very well and are excellent for pancakes, baking, and sauces. The red huckleberry ripens mid-summer to fall, depending on elevation and southern exposure.

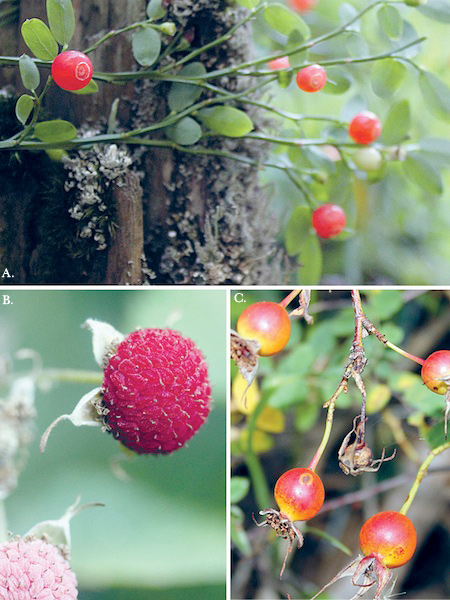

A. RED HUCKLEBERRIES B. THIMBLEBERRY C. ROSEHIPS

Salal Berry (Gaultheria shallon) Salal leaves are a major cash crop in the Pacific Northwest. Their main use is as a florist green. The leaves are oval and thick with a waxy appearance to the surface. The berries are also a prime food source for bears and other animals. Salal berries ripen in the fall and have a dry somewhat mealy texture but fine huckleberry-like flavour. The berries contain high levels of pectin and make a truly excellent jam or jelly. I also use the pulp to infuse vinegar and alcohol.

Salal was a widely distributed and abundant berry on the coast and very important to First Nations. The berries were eaten fresh or dried into cakes for use in the winter months. The cakes were dipped in eulachon grease (from a small ocean smelt, processed for its rich oil). Making the cakes was quite a process. One method was to drop hot rocks into cedar boxes to reduce the berries into paste. The paste was dried in rectangular boxes lined with skunk cabbage leaves and sometimes smoked over an alder fire. This produced an aromatic and nutrient-dense cake.

The plant is dominant in the undergrowth edges of forests. Areas above some beaches are so thick with salal they are almost impenetrable.

Salmonberry (Rubus spectabilis) These berries were named for their resemblance to salmon eggs and they often grow alongside streams and areas with available moisture. The berry slips easily from the base and in this way is similar to a raspberry. There are a few colour variations in the berries, some are salmon orange with a red tinge and other berries ripen to a deep red colour. The berry is moderately sweet and highly perishable. They are best eaten as a treat on the trail or mixed with other berries.

The salmonberry is one of the earlier ripening berries, sometimes as early as late June. The flower is a beautiful pink and lilac blossom, good in salads but often filled with tiny insects. (To get rid of bugs, soak the blossoms in cold, salted water before draining and using.) The leaves appear in groups of three, with the leading edge slightly larger than the two side leaves. They have a toothed edge and soft texture.

Local First Nations groups ate the new sprouts in spring and the berries in early summer. The sprouts (or new shoots) were peeled and eaten with salmon or eulachon grease. The berries were eaten fresh as they are too watery to dry with any success.

Thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus) The thimbleberry plant is characterized by large maple-like leaves and smooth, thorn-less branches. The leaves have a fine-toothed edge and are softly fuzzy. It is a common plant of the region, often growing next to salmonberry and blackberry bushes. The berry is a shallow fruit, very similar in appearance to a raspberry. Ripe fruit takes on a reddish or almost black tone. These berries are a little dry but the flavour is excellent. I often use them to infuse vinegar.

The First Nations used the berry extensively for drying, often mixing them with salal berries. On the west coast of Vancouver Island, they made a special cake with thimbleberries and dried clams. The cakes were flattened and sundried. The new sprouts were also peeled and eaten with eulachon grease.

Wild Strawberry (Fragaria spp.) Strawberry is common as a ground cover at the edge of pathways and fields. The berries fruit in late summer and are very tiny. The berries are so small it takes herculean effort to pick any quantity. I usually just use them for a tiny flavour burst while on hiking trails. In addition to these tasty small berries, the leaves of the plant are rich in vitamin C and make a good tea, fresh or dried. The medicinal uses are mainly tea used for urinary tract infections, promoting heart health, and boosting the immune system.

Many of the greens, berries, and herbs we hunt for the table are not native to the Pacific Northwest. They spread with the migration of people and were helped along in many cases by animals and birds. Dandelions, lamb’s quarters, sorrel, and many others were cultivated as herbs or soup ingredients (potage) and encouraged to grow beyond the confines of the garden. And grow they did. Many of the plants are now considered invasive species that reduce the value of other commercial field crops, such as hay. Corporations have spent billions developing herbicides and genetically engineering crops to lessen the impact of the cursed “weeds.” It is ironic that many of the weeds are more nutritious than the crops we try to protect. They are also available for free. I would imagine this greatly irritates those who massage the corporations’ profit calculations.

There are many poisonous plants out there. The correct identification of plants is therefore critical. Many plants have poisonous look-alikes that can easily confuse people. Only eat what you are 100 percent sure of.

I only pick plants that are abundant. Many plants are found in specific ecosystems; sometimes they are very sensitive and can even be endangered by disturbing and harvesting the plants. I try to avoid these plants, even if they have a long history of use in the region.

Important examples of plants to avoid are regional flower bulbs. Many plants like camas or forest lily bulbs were once commonly eaten as delicacies by local First Nations. These plants exist in the wild today, but traditionally they were harvested in meadows and often tended in “forest gardens” to encourage the production of plant material. Several of these commodities were treated as money or served to very special guests as a sign of the highest respect. Many of the techniques for increasing production have been lost or discouraged (like burning meadows to promote growth). In many cases, habitat destruction has limited, and in some instances jeopardized, the continued harvest of these plants. For this reason, I made a conscious effort here not to focus on too many wild plants that have edible tubers and roots. The potential environmental damage does not justify the reward. One notable exception is the taproot of the burdock plant. Burdock is an abundant (some would say too abundant) invasive species and happens to be very delicious.

Broadleaf Dock and Curly Dock (Rumex spp.), and Burdock (Arctium spp.) The dock family is distributed all over the world and is a good green for salads and cooking. The leaves are best in spring or when the plants are young (they can appear all through the growing season). In Japan, burdock is known as gobo. It is a significant vegetable in many Asian countries including Korea and China. Burdock root is very nutritious and is a good source of potassium, calcium, and amino acids. In Chinese traditional medicine, burdock is used as a blood-purifying tonic and is also thought to promote healthy skin and hair.

Broadleaf dock (Rumex obtusifolius) leaves are elliptical when young and mature into a long arrow-shaped leaf. The mature leaves are very bitter. Broadleaf dock can be used interchangeably with curly dock (Rumex crispus), which is distinguished by the curly edge to the leaf. There is, however, a significant amount of variation in leaf size and shape between the two plants.

Dock leaves (particularly the tips) and seeds are edible. It is interesting to note that dock seeds are toxic to poultry in large doses. To prepare the leaves, strip the green from the stem (much like you would prepare kale), chop, and sauté or blanch. The flavour is fairly dominant, similar to Swiss chard, and is often used in a blend of milder, cooked wild greens.

Burdock (Arctium lappa) is a larger plant that shoots up stalks topped with burrs. The taproot is the prize; you must dig to remove the whole root. The deep root may go down into the soil for more than 24 inches (60 cm). Burdock is distinguished from common dock by the presence of fuzzy white hairs on the underside of the burdock leaf.

Chickweed (Stellaria media) Chickweed is a very common plant that has widespread distribution. The plant has oval to triangular leaves and pretty white flowers. The stem has a distinctive row of hairs on one side. When the conditions are right, the plant can form huge ground cover “carpets” that sprout in the early spring and may reseed and continue producing throughout the growing season. Chickweed has a mild flavour, is packed full of nutrition, and is an excellent source of vitamins and phytonutrients. Chickweed prefers acidic soils but can often be found growing wild in both gardens and in the cracks of sidewalks. There is a long list of ailments that the chickweed is prescribed for. It is a general body tonic with positive effects on your digestive and immune system.

For the best tasting chickweed, harvest only the top 2 inches (5 cm) of the plant. As the plant matures the lower stem becomes stringy and has a pronounced hay flavour. If you harvest a patch you can just trim off the edges with a pair of scissors. You may come back and repeatedly harvest the same patch.

Caution: Poisonous Look-Alike!

A plant called Scarlet pimpernel (Anagallis arvensis) appears similar to chickweed. Pimpernel has reddish flowers and smooth stems. Chickweed has white flowers and small hairs on the stems.

Common Cattail (Typha latifolia) This is a plant with many food uses, and there is evidence that early humans ate this plant as many as 30,000 years ago. It has edible parts that can be harvested throughout the year and consequently was an important plant for early foragers.

Traditionally, the roots were used by First Nations peoples and ground into nutrient-dense flour. The ripe cattail heads were ground and used as a thickening and binding flour. Today, the tender bases of the leaves continue to be eaten raw or cooked and are delicious. The green flower spikes can be boiled or baked and eaten. In the fall the roots become very starchy and can be pounded in water. The starch will drop to the bottom and can be drained and dried out to form a protein-rich powder.

Cattail is found in many locations where water is present, such as in lakes, swamps, ditches, etc. However, you must be careful to look for nearby external sources of pollution and contamination.

Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) Dandelion is a very common inhabitant of both urban and rural areas. It was introduced as a pot-herb by immigrants and took off in a mad dash around the continent. Dandelion leaves are distinguished by the jagged downward-toothed edges (looking like lions’ teeth). The young greens are very nutritious and tender in the spring. Dandelions will always have some component of bitterness and they become increasingly bitter as they mature. Exposure to sunlight is a key factor in developing these bitter compounds. Dandelions that grow in areas that are shaded have milder tasting leaves. In addition, greens that grow rapidly (for example, in the rich soil of a garden) also tend to be better choices for the table. The young leaves are eaten as salad greens or cooked greens. Harvest the young leaves at the core of the plant for best results.

Cooking tends to slightly lessen the bitterness of the leaves and allows you to add components to balance the flavour (for example, salt, garlic, lemon, etc). The plant is used medicinally to aid digestion and to treat certain skin conditions. It has laxative and diuretic effects.

The whole plant has been used in many forms for centuries. The unopened flower heads are particularly delicious. The flowers are made into wine and dried for tea. The root is roasted to make a beverage or infused to make salves and balms for skin ailments. The best part of the plant may be the crown of younger plants. This is the whitish centre of the plant from which the flower stock of the plant will shoot up. It is tender and aromatic and makes a nice addition to a stir-fry or an intriguing pickle.

Daylily (Hemerocallis fulva and other species) The most common variant is the Orange Daylily. It is a plant that originated in China and was introduced and spread around the planet. The plant is distinguished by the beautiful orange flowers and multiple slim flower buds. The leaves are used in Chinese cooking and medicine where they are known as “golden needles.” There are many colour variations to the daylilies. The unopened flowers are referred to as buds and are excellent in stir-fries or eaten raw in salads.

There are other true lilies in the Pacific Northwest (Lilium spp.). These occur in forest and alpine areas. Many of these plants are sensitive to harvest and some are endangered. I do not recommend foraging for these lilies.

Field Mustard (Brassica rapa) Mustard is a very common plant of our fields and roadsides. Anywhere the soils are disturbed, wild mustard can take hold. There are several variants in the Brassica family that appear and most are interchangeable. You will probably first recognize the plant when in flower with bright yellow petals on a long, upright stalk. The leaves are lobed with a toothed edge, and there are often smaller lobes off-shooting from the base of bigger leaves. It is related to the radish and turnip families.

The leaves are tasty in the spring for salads or cooking, and the flower tops can be used as a vegetable. Once the plant flowers, edible seedpods develop. When the pods dry out and mature, they will contain reddish-brown mustard seeds.

Fireweed (Chamerion angustifolium) Fireweed is a tall and elegant plant that forms long clusters of flowers with four purple petals. The name fireweed comes from the plant’s tendency to be the first to sprout up after an area has been burned. They also like damp areas and frequently line ditches and fields in the region. The tender shoots are edible and have a pleasant mild flavour. The plant flowers in late spring and early summer. The leaves are long and narrow. Beekeepers rely on the flowers to feed their forest edge beehives. Fireweed honey is one of the best in the Pacific Northwest.

Fireweed was an important spring food for First Nations. The young leaves were used as a salad or cooked with other greens. The inner parts of the stem are sweet and were often scraped off with the teeth. The young shoots were made into a tea and were believed to be a health tonic and blood purifier.

Fireweed is an excellent source of vitamins C and A. Ointment made from the plant is used as a balm to sooth irritated skin. Harvest the young leaves and sprouts in the spring. In the summer, you can eat the unopened flower buds as a vegetable.

Lamb’s Quarters, or Wild Spinach (Chenopodium album) This plant is a common urban and countryside weed. It is recognized by its tall and majestic stature. When the plant flowers, it is distinguished by a silver to pink blush around the centre of the flower. Lamb’s quarters is another powerhouse of nutrients and vitamins. The leaves are an excellent source of potassium, calcium, and manganese with very high levels of vitamins (K, A, and C). It is renowned as a general body tonic and helps boost the immune system and metabolism.

When mature, the leaves contain higher levels of sodium and oxalic acid (linked to kidney stones). You should be cautious with this plant if you have a history of issues with kidney stones. The young leaves should be eaten (in moderation) in the spring, as the plant also becomes bitter as it ages. The seeds are highly nutritious (related to quinoa), and both the leaves and seeds are used extensively in Indian cuisine (where it is called bathua).

The whole plant can be eaten during most of its growing life. The young leaves are fresh and green tasting in a salad, and the larger leaves can be cooked like spinach. The flower tops can be cooked and eaten as a vegetable. And the seeds can be used much like quinoa. Soak the seeds before cooking to remove a little of the bitterness.

Caution: Poisonous Look-Alike!

Hairy nightshade (Solanum sarrachoides) can look very similar to lamb’s quarters. The difference is nightshade has small hairs on the stem and leaves and has a large white flower whereas lamb’s quarters has a powdery (actually waxy) dusting on the centre of the growing tips and is hairless. When lamb’s quarters is mature, it produces green flower buds that contain reddish-brown seeds.

Mallow (Malva neglecta) A common and widely distributed plant, mallow is similar in shape to the common geranium and sports beautiful white-and-pink flowers. Its cousin marsh mallow (Althaea officinalis) is often grown as a garden plant and has frequently escaped and populated the wild. Both plants contain a gelling agent that thickens foods into stable foam. They were initially used to make the famous namesake marshmallow (which is today made primarily with gelatin).

Mallow grows in rich, compact soil and is common on the fringes of civilization. The leaves are edible and are usually cooked to make the texture a little more palatable. They have a beautiful, geometric shape with folds extending out from the centre of the leaf to create a ruffled edge. If using the leaves raw, soak in water to rehydrate. They will quickly wilt if left out to dry. The leaves make great tempura. The flowers are white with pink blushes or lines. Once the plant flowers, there are small fruits or peas that form. The peas are edible and are a rich source of the thickening (mucilaginous) qualities as the leaves and stems. The peas can be added to soups and stew for a similar effect to okra.

Miner’s Lettuce (Claytonia perfoliata) This might be one of my favourite springtime greens. It is an introduced plant that has widespread range in our region. It grows under mature trees and lines ditches and wet areas. The leaves are triangular to start and round as they mature. The plant flowers from the centre of the leaf, producing a short stem and a delicate white flower. The flavour is mild, spinach-like with a slightly citrus flavour. The greens are a wonderful addition to a salad bowl. The plant is a good source of vitamin C and an excellent source of plant protein and fibre.

The plant is one of the first to sprout in the spring and creates large and spectacular masses of greenery. Once temperatures rise and the rainfalls diminish, the plant withers and dies, eventually disappearing to then be replaced by other wild plants. The stem is tender and the plant is easily harvested by pinching off the flower at the stem. The leaves are not bitter and are excellent even after the plant has flowered. Miner’s lettuce is best eaten raw and can form the mild base of a delicious wild foods salad. It is also a great green to purée into smoothies. When the plants are mature with long stems, I like to chop the stems and leaves and quickly sauté with garlic for a tasty vegetable.

WILD MINT

Mint (Mentha arvensis) Wild mint is common in the wet areas and fields of the region. You might notice it when the plant flowers in the summer. The purple-blue flowers are very pretty and tend to produce short spikes of colour often in a sea of green. The plant is most tender in the early summer and becomes more intensely minty as the summer progresses. Wild mint is strongly flavoured and has a slight bitter edge. It makes an excellent tea and is a nice addition to salads.

Oxeye Daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare) This daisy is a common wildflower that is abundant in fields and along roadsides in the region. The white petals and yellow centre are very visible in the summer when the plant flowers by the thousands. The leaves in the spring are one of the best edibles available, growing as a rosette of green, beautifully cut leaves. The flavour is reminiscent of green apples and sage with a sweet aftertaste. Add young leaves to salad mixes or mix into dressing and sauces. A tea from the leaves can be used as a mild, relaxing tonic.

As the plant matures, a green flower stem shoots up with a tightly closed emerging flower head. The whole shoot is edible and tasty as a vegetable or soup herb. The flower buds resemble caper berries and can be pickled. Once the flower opens up, the petals can be used in salads and dried for tea. The greens become bitter once the plant flowers and have a very pungent and somewhat overpowering aroma. The mature leaves were traditionally used as an insect repellant.

Pineapple Weed (Matricaria discoidea) The aromatic flower is cone shaped and lacks any petals. The flowers are used to make a soothing tea and can be used to flavour a wide range of dressings and even baked goods. The tea is reputed to be soothing for a cold and helps aid digestion and calm an upset stomach. It also has strong anti-bacterial properties and is reputed to have anti-inflammatory effects.

The plant favours the edges of inhabited areas and likes to pop up in compacted soil. The plant first flowers in hot weather and will keep growing throughout the warm months. Harvest the plant by removing the tips of the cone-shaped flowers and leaves. The flowers are great in salads and can also be pickled or preserved in syrup. The flowers are excellent dried and will make a wonderful tea—one of the best in fact.

Purslane (Portulaca oleracea) Purslane is a succulent plant that loves the hot weather. It occurs in summer and is rich in flavour. The leaves are tender and exceptionally high in minerals and omega-3 fatty acids. Purslane is an excellent source of antioxidants and deserves to be more widely known. It is used in traditional Chinese medicine to combat infections and can be applied to insect bites to stop the itching.

The young leaves have a reddish tinge and are very plump. The plant has a branching structure that tends to spread quickly over the ground. The plant produces a small yellow flower that will produce a tiny, cup-like structure filled with seeds. The tender stems and leaves are edible. The tips and leaves are great in a salad; the whole plant is great as a cooked vegetable and has a pleasant, sour flavour and soft, gelatinous texture. Blanch the leaves in boiling salted water for 2 to 3 minutes, then refresh in cold water. The blanched leaves can also be puréed into sauces and soups.

Sheep Sorrel (Rumex acetosella) Sorrel has a pleasant sour taste that is used to provide tartness to dishes and is used as a curdling agent when making some types of cheese. Medicinally, the plant was an important First Nations herb used for treating inflammation, fevers, and digestive issues. It is considered to be a whole body tonic and useful for detoxification and cell regeneration.

It is a cousin of the dock family of greens and both are related to wild buckwheat. The plant flowers with tall, reddish spikes that are very common in fields and at the edges of forests. The leaves are lance shaped with small spikes at the base of the leaf (making it look like a little rocket). It reproduces by seed and by sending out rhizomes. This makes the plant difficult to remove from gardens and has ensured the plant is widely available throughout the growing season.

When harvesting sorrel, look for large, healthy clumps and cut with a pair of scissors. Back in the kitchen, soak in water and spin dry. Remove the tough stems and use leaves in salads or as an herb for seasoning.

A. PINEAPPLE WEED B. DAYLILY C. MALLOW LEAF

Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica) A common plant in this region, nettle is identified by its sharply serrated edges. The leaves grow in opposite pairs on either side of the hairy stem of the plant. It favours moist areas at the edges of roads and trails and is often seen in the rich soils near barnyards. Nettle often forms in large banks of leaves. To protect yourself when picking nettles, wear garden gloves and use a pair of scissors. Pick just the top tips of the plant and the first pair of good leaves on the stalk, before the plant has a chance to flower. When the plant is mature, it grows tiny crystals that are irritating to the digestive system. When you get home, wash the nettles in cold water and drain before using them in cooking.

Stinging nettles contain histamines. They have many therapeutic properties and are taken to treat allergies. They are also a popular folk remedy for arthritis. The leaves are rich in vitamin C and A and are good sources of iron, potassium, manganese, and calcium. The leaves are a very good source of protein. The young leaf tops dry well and are often used to make a therapeutic tea. Blanch nettles in boiling water to remove the stinging qualities. They can then be frozen for storage for several months.

Sweet Cicely (Osmorhiza longistylis) The plant displays beautiful, fern-like leaves with the faint scent of anise. This is another introduced plant that has found a home in the Pacific Northwest. Look for sweet cicely in moist, wooded areas. The plant flowers with large, multi-flowered white blossoms that turn into long elliptical seeds. The seedpods have a strong anise flavour when fresh. They dry out quickly and the flavour diminishes. The roots have the same strong, licorice flavour and can be used in savoury and sweet dishes. Leaves, seeds, and roots can be dried to make a fine addition to tea mixes.

WILD ONION

Wild Onion, especially the Nodding Onion (Allium cernuum) Wild onions are found in coastal valleys and open forest meadows. I look for moist areas that get access to sunshine. There is a characteristic onion odour that often is apparent before you see the plant. The nodding onion is named for its habit of drooping (or nodding) toward the ground. The flowers are white or pink and form seed heads.

The onion bulb and leaves are sweetest in spring, becoming quite strong flavoured as the season progresses. First Nations loved to roast the bulbs in fire pits; the roasted bulbs were served to important visitors.

Wild Roses (Rosa spp.) The flowers, leaves (when young), and hips are all edible. The leaves and hips are rich in vitamins C, A, and E. The plant is easily recognizable and is considered a prime food for survival situations. There has been much recent research into the promising anti-cancer properties of the rose and the plant is often used as part of a detoxifying program.

The flowers bloom in late May and soon drop their petals to reveal green seedpods called hips. Over the following months the hips ripen and turn reddish orange. Harvest after the first frost for the sweetest rosehip flesh. The interior contains tiny hairs that must be strained out of any product made for consumption. The hairs are very irritating to the digestive system.

Leaf-bearing trees bring us many wonderful foods—apples, pears, stone fruits, and plums are the most common. They have also escaped captivity and many wild versions exist in our region and throughout the world. I could fill a boot just on the product of trees but instead offer a few of my favourite local wild products.

Bigleaf Maple (Acer macrophyllum) Western maples are majestic trees that can grow to 65 feet (20 m) tall. They are also home to lush carpets of moss that often line the trunks. The licorice fern (a fern with an edible root) likes to grow out of these moss patches.

In December through February, the trees are tapped for a distinctive syrup. It takes 60 to 70 quarts (60–70 L) of sap to make 1 quart (1 L) of syrup. The syrup is delicious with a slight mineral and acidic edge that makes it stand out from traditional maple syrup. In the spring, the tree flowers and the flowers can be eaten or used to infuse syrups. I have also cooked the blossoms into fritters or tempura. In the fall, the maples form keys (seeds) that can be boiled and eaten as a snack.

A. LICORICE FERN LEAVES B. MOSS ON BIGLEAF MAPLE C. HAZELNUTS

Crabapple (Malus spp.) Tucked into gardens and forest edges, the crabapple is a common wild plant and ornamental in many old farmyards and gardens. The fruit is small and often sour or bitter. Cooking transforms it into something special and the crabapple has a significant quantity of pectin, making it a good fruit to mix with wild berries to create beautiful jellies.

Use the crabapple in baking as you would a regular apple; they just need a little extra sweetening to compensate for the bitter and tannic edge. They are excellent pickled with spices and a stick or two of cinnamon.

Hazelnut (Corylus cornuta) The hazelnut is a common native tree in the region and (some, like my dog Oliver, say unfortunately) a favourite food of squirrels. The tree forms bushes and trees up to 18 feet (6 m) in height. The nuts are fully formed by August and can be eaten raw or allowed to dry in the shell before shucking. Roasting the nuts brings out deep, rich flavours. The tree bark has been traditionally used as a soothing tonic for sore throats and upset stomachs. Local First Nations picked the nuts and dried them out for winter use. They were most often eaten raw.

Plum (Prunus spp.) There are lots of wild plum trees dotting the landscape. Most are introduced species from Europe and Asia. You often don’t see the tree until it blooms with a profusion of white or pink blossoms in the spring. A common variety is the Japanese plum (Prunus salicina), which is found along pathways and streams in our region. The wild plums are small and tart with a sweet finish when ripe. The fruit may be yellow or reddish and may darken to deep purple when ripe. The fruit can be processed into preserves or jelly, or used to infuse alcohol with a fine plum flavour.

Sumac (Rhus typhina or R. glabra) The sumac plant is most noticeable in summer when it flowers in a deep red cone. The staghorn sumac (R. typhina) is grown as an ornamental all over the world and has escaped into the countryside. Sumac flowers are harvested in late summer and early fall when they have a fine lemony acidity. The dried flowers are used to make a kind of lemonade-like drink. In the Middle East, sumac is used as a seasoning, most famously as the tart component of the spice mix called za’atar.

Caution: Poisonous Look-Alike!

There is a bad cousin of the edible sumac, commonly called poison sumac (Toxicodendron vernix). It displays white berries and should be easy to distinguish and avoid.

Most of the region’s fir, spruce, and pine trees are edible. The needles make an acceptable tea and have been used as medicinal ingredients for centuries. The raw needles contain significant levels of vitamin C and a tea made from the needles is soothing to sore throats and helps open up the airways if you are suffering from congestion. My personal favourite is the grand fir, followed closely by Douglas fir.

Douglas Fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) The Douglas fir is a magnificent tree any way you look at it. It is often the tree making up the giant, old-growth forests of the northern coast. The biggest tree recorded is over 350 feet (over 105 m). Douglas firs can obtain diameters approaching 16 feet (about 4.9 m). They are important trees for mushroom foraging, hosting a variety of edible fungi in their root systems. The leaves are also highly aromatic and can be used in teas, infusions, and broths.

Grand Fir (Abies grandis) This tree reminds me of the Christmases of my youth. Later, I discovered it was a wonderful aromatic and a fine addition to food and drinks. I often serve grand fir tea to guests, surprising them with the fine and delicate flavour.

The tree is a tall, majestic specimen that can reach heights topping 200 feet (60 m). The needles are distinctive in that they branch out flatly from the branch. Each tip is slightly notched and the backside of the needle has a green strip bound by white strips above and below.

In the spring, the new tips are soft and highly aromatic. They are used to infuse honey, syrup, vinegar, and oil. I also process the new tips with sea salt to preserve the essential oils and make a lovely green salt for curing and seasoning food. The needles are edible year-round and make an acceptable tea year-round.

Sitka Spruce (Picea sitchensis) The Sitka is another magnificent tree of the coast. It rivals the Douglas fir in size and specimens have reached over 300 feet (over 90 m) in height. The needles are like a typical spruce and very stiff. The needles will hurt if tapped into your skin. In the spring, the new shoots are soft and can be used to infuse syrups and prepare essential oils.

We live in a magical place for mushrooms. The Pacific Northwest is washed with warm rains from the Pacific and our temperate climate is perfect for the production of mushrooms. Our mushrooms are often known for the gigantic size they can reach, with many of the largest specimens on the planet recorded in our forests and fields. The chanterelle is the most abundant of the species and the prime mushroom for beginners to seek out.

Mushrooms have complex relationships with trees and the environment. They are critical to the health of our planet and play an important role in keeping the world growing and composting the remains when the growth finally ends. The science of fungi is continually evolving. Techniques like DNA analysis have been used to help identify and classify mushrooms. Many new species have been added or names changed in recent times. This means that many old field books may not have current information on the mushroom and in some cases the edibility of some mushrooms has been brought into question. One example is the honey mushroom (Armillaria mellea). A mushroom that was frequently eaten and listed as edible, it is now thought to cause kidney damage if eaten in large quantities over a number of years. A little will probably not hurt you, but a steady diet of honey mushrooms is probably not wise.

There are many mushroom species out there. Some estimates are in the range of 10,000 species for the Pacific Northwest. Only a select few are edible (maybe 50 species). This leaves a lot of mushrooms that you should avoid. The best advice is keep to a small group of fungi that you can confidently identify and leave the rest in the forests and fields. Chanterelles and morels are relatively easy to identify and occur in some abundance. That’s a good place to start your mushroom-foraging journey.

Chanterelles The chanterelle family includes many strange and wonderfully coloured fungi, from pale, creamy white to psychedelic shades of electric blue. Yellow chanterelles are abundant in the Pacific Northwest, where the forests often provide bumper crops. On many occasions, I have encountered several hundred chanterelles over the course of a short hike. This abundance has led to increased availability in public markets and specialty stores; chanterelles are continually gaining wider exposure. Dry chanterelles are a step down in quality from fresh as the drying process renders the mushroom very tough, with a slightly bitter and peppery taste. Frozen chanterelles are a good addition to soups and stews.

The yellow chanterelle is probably the best mushroom with which to start your foraging career. It is fairly easy to identify, abundant, and the mushrooms that look like it won’t kill you (always a bonus). The chanterelle exists over most of the temperate zones of the planet. It is beloved in Europe, Asia, North America, South America, and South Africa. The chanterelle also happens to taste great, making it a good mushroom to get to know.

A. WHITE CHANTERELLES B. PORCINI C. LOBSTER MUSHROOMS

Yellow Chanterelle, or Pacific Golden Chanterelle (Cantharellus formosus and other species) Chanterelles are many people’s favourite wild mushroom. They have a beautiful elegant form, are plentiful, and are unique in several characteristics. The bright yellow-orange colour also allows them to stick out from the forest floor.

The chanterelle really likes locations with a deep, lush carpet of moss along with a fairly mature canopy of trees. I’ve had great success in older, second-growth forests and mature (15–20 year), third-growth forests. Find one chanterelle and a careful search will usually turn up more hiding under the surrounding trees. In France, a smaller variety of chanterelle is known as the girolle (Cantharellus cibarius). These may also occur in eastern North America. Our Pacific variety is known for its huge size and paler underside. There is a second, large Pacific Northwest variety called Cantharellus cascadensis. It is very similar to the C. formosus, with a slightly brighter yellow cap and a thin, wavy edge. A third local variant is the C. cibarius var. roseocanus. It is the smallest, but most fragrant, of the yellow chanterelles found in the Pacific Northwest. Look for chanterelles in flat, forested areas at the base of hills and along the slopes. The chanterelle tends to fruit under Douglas fir trees in the Pacific Northwest.

White Chanterelle (Cantharellus subalbidus) This delicious chanterelle is a cousin of the yellow chanterelle. The colour is pale white to cream when fresh. After picking, the mushrooms often discolour around the edges and the flesh appears to be slightly bruised in darker shades of orange. The stem of the white chanterelle is often much thicker than the common yellow varieties. The flesh is tender and mild and it is one of my favourite mushrooms for chowders and soups. The white chanterelle is often found in great numbers. The flesh can become saturated if there is too much moisture and they are sometimes attacked by fungus gnats and moulds near the end of the season. The white chanterelle does not like cold temperatures and will quickly rot if frozen. Look for white chanterelles at the edges of forests and in stands of salal and ferns.

A. BLACK MORELS B. HEDGEHOG MUSHROOMS

Winter Chanterelle, Yellow Foot Chanterelle, or Funnel Chanterelle (Craterellus tubaeformis) The funnel chanterelle is a common late-season mushroom, particularly after heavy rains. It was formerly called the Cantharellus tubaeformis. The mushroom has a delicate, funnel-shaped cap that is hollow in the middle. The stem of the mushroom is yellow and hollow. Look for this mushroom growing near or on rotting wood.

They are tasty sautéed and are often found in dried mushroom mixtures (particularly from France). This delicate mushroom quickly loses its shape after picking and can degenerate into a soggy, larva-infected mass if not stored properly. Wrap the mushrooms in plenty of paper towels, and refrigerate in a container that provides lots of side ventilation. Drying the mushroom actually helps to concentrate the flavour and results in a pleasing, firm texture. Locally, we find the winter chanterelle among the Douglas fir and hemlock trees.

Morels Morels are delicious fresh or dried, and are considered one of the top culinary mushrooms. They should always be eaten cooked, as the raw mushrooms can cause allergic reactions in many people.

Morels are sometimes difficult to forage because they tend to blend in with the surrounding landscape. The morel has a distinctive cone shape that is often pointed. The surface resembles a sponge with lots of ridges and wrinkles. In an average spring, morels will appear soon after the crocus flowers bloom. Thousands of morels often sprout the year following a forest fire. Morels seem to like disturbances and often sprout from road cuts, excavations, and fallen trees.

The classification of morels is very complex and has undergone much revision in the last few years. The following are the region’s most common species.

Black Morel (Morchella elata and other species) The black morel is one of the first morels to appear in the spring. The black varieties are particularly difficult to see in the forest. The head looks almost identical to a fallen pinecone. To successfully forage for the black morel, you often have to key on sighting the white stem and then focus in on the black cap of the mushroom. The morel occurs early in the spring and may be present well into summer. The black morel can also occur in high alpine meadows, fruiting much later than morels at a lower altitude. Look for the black morel under conifers, poplars, and shrub undergrowth. Morels seem to particularly like to fruit under aspen and pine trees but are found in a wide range of habitat.

A. MIXED HARVEST OF WILD MUSHROOMS B. PINE MUSHROOM CLOSEUP C. CAULIFLOWER FUNGUS

Common Morel (Morchella esculenta and other species) Common morels fruit after the black morel and can fruit in huge numbers if the conditions are right. They are often found at lower elevations than other morels. They are similar in structure to the black morel, but with the surface looking grey to dull yellow, as opposed to black. The common morel prefers the late spring and needs a long warm spell of weather after a particularly cold winter. It seems to be partial to apple and cherry orchards, as well as aspen forests, but they also appear in a wide variety of habitats.

Burnsite Morel (Morchella tomentosa and other species) A West Coast variation of the black morel, the burnsite morel occurs up to two years after a forest fire, usually reproducing in prolific amounts. These morels appear similar to the black and common varieties and are basically distinguished by the habitat in which they are found. New DNA evidence has greatly reorganized the entire category of morels. It is thought these morels are the first to return after a fire to take advantage of the lack of competition from other mushrooms. The morels also feed on the burnt plant materials of the forest floor and help recycle the nutrients. These morels will have a distinct smoky flavour, particularly when dried.

Western Blond Morel (Morchella frustrata) This morel is a recent addition to the scientific catalogue. It is related to the common morel but differs in subtle anatomical details. The western blond morel is one of the tastiest members of the morel family. It is distinguished by the pale white-yellow surface of the mushroom. It is often significantly more rounded than the pointed black and common morels. Locally, it can grow to gigantic proportions, making one mushroom a good part of meal. I have foraged several specimens that weighed over 1 pound (454 g) each. The western blond morel seems to like steep slopes and plateaus. It also likes older growth forests of conifer trees and patches of disturbed soil.

Other Species Recommended for Mushroom Foraging There are thought to be about 10,000 species of mushrooms in the Pacific Northwest. A few are poisonous and most are of no value for collecting for the tables. Outside of chanterelles and morels, the risk of misidentification increases. However, there are a few species that are particularly tasty and worth getting to know.

Cauliflower Fungus (Sparassis crispa) This is a unique, large fungus that looks like a compact bunch of ribbons. It’s common name, cauliflower mushroom, comes from its passing resemblance to this great garden vegetable. This mushroom, however, will be found growing on a dead tree and not in your garden. Though not common, this is an excellent find particularly since one mushroom may weigh several pounds. Soak the whole mushroom in a solution of cold water and salt to rid it of any insect visitors. The aroma is very appealing and the crisp texture makes it one of the best edible mushrooms. Look for the fungus growing at the base of rotting Douglas fir stumps.

Field Mushrooms (various Agaricus species) Similar to the store-bought common white button mushroom, wild field mushrooms are common and an excellent find. Be very careful to distinguish the mushroom from the entire Amanita family. If there is any doubt, do not consume the mushrooms. Many poisonings are due to confusion over these two mushroom families. The undercap of the field mushroom should be pink when young, changing to chocolate brown as the mushroom matures. Do not pick button mushrooms with white or yellow gills. Look for field mushrooms in grassy meadows, particularly where animals are grazing. Be particularly careful when identifying Agaricus mushrooms in the forest or at the edge of fields.

Caution: Poisonous Look-Alike!

Destroying Angel (Amanita ocreata) and Death Cap (Amanita phalloides): Young Amanita buttons look similar to young Agaricus mushrooms. A. ocreata is native to the Pacific Northwest but rare in British Columbia. It contains deadly amatoxins. Poisoning symptoms include vomiting and intestinal issues that begin 2 to 3 days after consumption. Unfortunately internal damage continues and compromises the function of the kidney and liver for the next 5 to 6 days. A. phalloides is a European species that has been introduced into North America. It is out there and does poison people. It will have an olive green hue to the cap. When young, the amanitas appear egg shaped and are covered by a thin veil of tissue. There are other lots of other amanitas to be careful about.

A. MUSHROOM HARVEST B. WILD OYSTER MUSHROOMS C. CLEANED PINE MUSHROOM BUTTONS

Hedgehog Mushroom (Hydnum repandum) At first glance, this mushroom looks like a large chanterelle. The underside of the cap has a shredded appearance that resembles a tiny shag carpet. The flesh is firm and dense and is quite delicious in soups or stews. It makes a good dried mushroom. Look for hedgehog mushrooms in the same terrain as chanterelles. They do tend to like the bottom of valleys and vales, particularly if there is water nearby.

Lobster Mushroom (Hypomyces lactifluorum) A vivid red-orange mushroom, this fungus is a joint effort between a host mushroom (usually a Russula brevipes or R. cascadensis in our area) and a parasite that attacks and transforms the host into an excellent edible mushroom. Guidebooks warn that sometimes the host mushroom can be poisonous. Pickers should identify the mushrooms surrounding the lobster mushroom to identify the host. The lobster mushroom has a crusty, florescent orange exterior, firm flesh, and a sweet flavour. The host mushroom is usually a large white, gilled mushroom before its transformation.

Caution: Identify the host mushrooms surrounding the lobster mushrooms. Only pick the lobster mushroom if you can confidently identify the host mushroom as non-poisonous.

Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus spp.) The oyster mushroom is typically a white to light grey, fan-shaped mushroom. It grows on dead deciduous trees (usually alder locally). The mushroom grows in clumps on broken trees and on deadfall near the banks of streams and rivers. The oyster mushroom is a good mushroom for the beginning forager because it is abundant and relatively safe to collect.

Pine Mushroom, or Matsutake (Tricholoma magnivelare) The mushroom has a firm, dense flesh and a spicy aroma that is reminiscent of cinnamon. The scent is a key factor in determining the identity of the pine mushroom. Look for the pine mushroom in higher altitudes in stands of mature Douglas fir and hemlock. At lower elevations, they occur in stands of pine and huckleberry. In the Pacific Northwest, the mushroom starts fruiting in late September and continues on until the first hard frosts (usually about mid-November). Once you have smelled a fresh pine mushroom, you may find the scent intoxicating. Unfortunately, this volatile aroma is largely lost when the mushroom is dried or frozen. Pine mushrooms can be used like truffles to infuse flavour into a wide variety of dishes.

Caution: Poisonous Look-Alike!

Smith’s amanita (Amanita smithiana) is very similar in appearance (as a small button), but the odour is not spicy. The mushroom can be pure white or with powdery scales on top. There is a shaggy fringe on the edge of the cap, extending to veil under the cap. It is also an imposing mushroom; it can be up to 8 inches (20 cm) tall. The spores and spore print will be white.

Porcini, or Cep (Boletus edulis) The porcini is characterized by a fat, light-brown top and a distinctive swollen base. There is some debate over the species name of our Pacific Northwest porcini. There may in fact be a different species that is yet to be determined. When the mushroom is young, the undercap will be whitish and firm. As it ages, it becomes yellow, darkening to green, and finally brown when it begins to break down. Also look for small pinholes in the sponge, signs that worms have penetrated the flesh.

Soft-fleshed porcini are often bitter and have a slimy texture. Firm small porcini (buttons) freeze well. Cook them partially frozen for the best results. Look for the porcini in two habitats: near the ocean at the top of beaches in the undergrowth and on the slopes and high alpine areas, particularly near lakes and streams.

Foraging on the seashore has been an important tool for humanity since the dawn of civilization. Seaweeds in particular are incredibly nutritious, abundant, and relatively easy to forage. The spring is best for many types of seaweed, but many are available year-round on our coast. Picking seaweed dislodged by tides and waves is the most sustainable way to harvest sea vegetables. Many are available in the intertidal zone that is exposed with the tides. Offshore kelp forests are important sanctuaries for fish and animals and therefore should be only selectively harvested, if at all. Most varieties of seaweed are also commercially available in stores as dried (and occasionally fresh) products. These products are often farmed and produced using sustainable processes.

Seaweed can begin to rot once it is removed from the ocean and allowed to warm up. Seaweed collected from dry beaches usually has a little stability. Seaweed harvested in ocean water should be kept moist until you can deal with it at home. I usually harvest small amounts moistened with seawater and transport them home in buckets to be processed in batches. Rinse kelp and Alaria (brown algae) in fresh water before drying. Laver and sea lettuce can be rinsed with salt water during harvesting.

Sea vegetables pack a lot into their small package—proteins, vitamins, and calcium are abundant. Seaweed is also reputed to help the body rid itself of toxins. Sodium alginate bonds with toxins and heavy metals and helps the body flush them from the system. Many seaweeds are edible raw and all make great dried product, reconstituting quickly to closely resemble the fresh product.

One brown seaweed, Flattened Acid Kelp (Desmarestia ligulata), releases sulfuric acid when removed from the ocean. It exists primarily in the lower tidal areas. This is one seaweed that obviously must not be collected.

Sea beans technically are land-based plants existing at the top of the intertidal zone. They are included in the sea vegetable category due to their ocean flavouring and high salt content.

Alaria Species, commonly California Wakame (Alaria marginata) Alaria is the genus name for a number of brown algae. It is best harvested in the spring and fall. It is common on rocky shorelines and attaches to boulders and ledges. The seaweed has a distinctive brown, ruffled blade with a lighter brown stem running down the leaf. The leaf is broad and shaped like a fern or feather. Most blades are less than 3 feet (1 m) in length. In the water, the buoyant central shaft floats the alaria like a raft.

Alaria is tasty raw or lightly dressed with a vinaigrette. It is a great seaweed for cooking into sauces and soups.

Bull Kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana and many other species) Common seaweed, known as kelp, is often seen washed up on beaches after storms. The plant is fast growing and anchors itself to the bottom of the seabed, with long, smooth blades growing from a central float. The plant can be used in many forms. The long whips can be pickled. The leaves can be used to wrap fish and vegetables for roasting. The entire plant can be dried and ground into powder.

Several varieties of kelp form vast kelp forests found along the coast. These are important breeding grounds for fish as well as habitat and protection for many species of ocean life.

Purple Laver, or Nori (Porphyra spp.) Look for laver on the beach from the high tide mark down to the waterline. It is sometimes tangled in with bull kelp or stranded on intertidal ledges. Nori has a very fine texture and the surface feels slippery. The leaves appear shiny and are almost transparent if held up to the light. There are several varieties and structures present on our shores. It may appear reddish brown when wet and dries to a dark purple sheen.

The seaweed is excellent fresh in the spring and makes a wonderful dried seaweed cake. Local First Nations dried the seaweed in spring when it is at its prime. The seaweed was dried in cakes on racks over fires or woodstoves, imparting a subtle, smoked flavour to the seaweed. In Japan, fresh seaweed is dried in thin sheets, used often for sushi or garnishing many dishes. I like to dry the nori in thin sheets using a food dehydrator.

Sea Bean (Salicornia spp.) This plant is found at the top of beaches in the zone where the highest tides reach. Sea beans are best in the summer months when the stems are plump and tender, before the plant flowers. They tend to grow in large and vigorous patches through the warm months and die back in the winter. It is best to soak the sea beans in cold water to refresh and remove a little of the salt before processing. Salicornia makes a great vegetable or pickle. Sea beans will keep well for a week to 10 days in the refrigerator. You can also quickly blanch them in boiling water, chill, bag, and freeze for several months.

Sea Lettuce (Ulva lactuca and other species) Look for sea lettuce floating on still pools of seawater or clinging to rocks or other seaweed. The leaves are bright green and have a thin and translucent appearance. Sometimes there is a whitish margin to the leaves. Sea lettuce thrives in areas with high nutrient levels. The mature leaves will grow up to 3 feet (1 m) in length. It is best harvested in the spring. In the summer, sea lettuce often dies off and begins to rot.

Modern shellfish foraging is hampered by the fact that shellfish are very sensitive to pollution and contamination. Shellfish are filter feeders that tend to concentrate toxins and pollutants. They are also prone to contamination from natural phenomena like toxic algae blooms (see PSP). These dangers lurk in shellfish that otherwise look healthy and taste fine. For these reasons, shellfish foraging is a relatively dangerous pastime that should only be undertaken in pristine areas, far from the influence of civilization and in areas that are not affected by shellfish bans.

Like many other wild foods, the most abundant products are those that are introduced species. The introduced species often flourish due to a lack of predators and a hardy constitution (needed to flourish in diverse environments). Many of the region’s beaches are dominated by the clams (Manila) and mussels that were introduced to the West Coast by oyster growers attempting to grow Japanese oysters in our waters. The native shellfish sometimes struggle to compete and are found in very limited areas. Local shellfish have a checkered history in resource management. Delicacies like abalone were overfished to the extent the fishery collapsed and it has yet to be re-established.

For these and many other reasons, you might be wise to avoid the wild harvest of these products and enjoy the efforts of professional harvesters and shellfish aquaculture farms. Even so, it is highly educational to find and observe these products in the wild.

We are spoiled here on the West Coast in our bounty of amazing shellfish. The ocean waters flowing down the coast from northern climates are rich with nutrients and very cold. This creates prime areas for shellfish production around the mid-zone of Vancouver Island. Cold waters are necessary for fine flavours, and nutrients are necessary for rapid growth and healthy shellfish.

A. SEAWEED B. JAPANESE OYSTER C. MUSSELS AND BARNACLES

Shellfish aquaculture (unlike salmon farming) is an industry that has largely been deemed sustainable and causes little harmful impact to the local environment. Shellfish need clean, nutrient-filled water and not much else. They are, however, subject to the effects of dangers like pollution and red tide. Red tide is an interesting phenomenon. Also called Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning (or PSP, see here), it is caused by a population explosion of tiny toxic plankton. Shellfish feed on these organisms and pass the effects on to the eater. When a Red Tide warning is posted, the harvest of shellfish is banned until the toxin levels are reduced to a safe level. All commercial shellfish in BC is tested to determine the safety of our products.

Shellfish were an important part of the local coastal First Nations diet. Recently, archaeologists discovered man-made terracing in clam-rich areas that have been termed “clam gardens.” These were areas that captured fine sands and made a great habitat for several types of clams.

Clam (Protothaca staminea and many other species) Local clams were a special food source for the local First Nations peoples. They harvested many varieties of clams and cockles. Some were wind dried and kept for use in the winter, some were baked in fire pits covered with seaweed for use in celebrations and potlatch ceremonies.

Most of the clams we see on the beaches today are Manila clams (Venerupis philippinarum), an introduced species that is known for its tender meat and small size. These clams are now found wild all over the coast and appear to have adapted well to our climate. The other common clams include butter clams (Saxidomus gigantea), cockles (Clinocardium spp.), and razor clams (Siliqua patula).

The Manila and littleneck (Protothaca staminea) clams appear high up on the beaches (the top third during low tide). If you are lucky enough to find a mud and gravel beach, the clams may be lurking only inches below the surface. Butter clams are a little farther down the tide line and can be buried up to 12 inches (30 cm) below the surface.

Of special interest is the geoduck clam (Panopea generosa). The common name comes from the First Nations phrase for “dig deep” and this massive clam is the king of the intertidal zone. Most modern harvesting is done by divers with hoses blowing seawater into the soft sediments to dislodge the clam. Geoducks are farmed by seeding the clams into appropriate foreshore. It does take up to 12 years to mature the clam to market sizes. Some geoducks are incredibly long lived, with some specimens living for over 100 years. The geoduck clam is highly valued in Asian cultures and is truly an impressive specimen.

Gooseneck Barnacle (Pollicipes polymerus) Let’s face it, these are bizarre-looking creatures. When I first encountered them in Spain, I thought I was looking at some alien creature. One bite and I was convinced, converted to a barnacle fan for life. The texture is chewy but the taste is surprisingly sweet and filled with the flavours of the ocean. These morsels are found deep in the intertidal zone or in areas with strong currents and in areas with surf-pounded rocks. The harvesting of these barnacles can be dangerous.

Mussel (Mytilus spp.) Mussels have a thin blue shell with waves of brown, purple, and black sometimes present. The peak time for mussels is in the fall, winter, and spring. Summer is the time for spawning and there are often elevated levels of biotoxins. The common wild blue mussel (Mytilus edulis) is abundant on rocks and shorelines all over Vancouver Island. Many commercial mussel farmers have selected the Mediterranean mussel (Mytilus galloprovincialis) and a new hybrid, the golden mussel (Limnoperna fortunei), for local cultivation.

Mussels can be gathered from rocks, outcrops, and ledges during low tide. They will often be linked together in clumps. Avoid pulling the string attaching the mussel to the rock. Avoid mussels that have been exposed to the air for long periods of time. Harvest as the tide is going out. Use mussels as soon as possible and keep refrigerated. Rinse the mussels in fresh water just before cooking to eliminate a little of the salt content.

Mussels do need a little more attention than most shellfish as they are somewhat more perishable. In a fresh mussel, the meat will be plump and sweet, filling the shell. As the mussel ages, it will feed on itself and wither in the shell. When a mussel dies, it starts to deteriorate quickly. Open shells are a sign of dead or dying mussels. You can try to close it to see if there is life still there, but if the shell springs back open, discard it. This is best to do before you cook the mussels. When cooking them, discard any mussels that do not open.

Oyster (Crassostrea gigas) The native oyster on this coast is the Olympia oyster (Ostreola conchaphila). The production is centred around the Puget Sound area but the oyster occurs sporadically all along the Pacific coast. Efforts are underway to restore the oyster on the coast. These efforts are being hampered by pollution, contamination, and predator concerns. This was the oyster that fed First Nations groups all along the coast.

Most of our local food oysters are variants on the Japanese oyster (Crassostrea gigas) that has been cultivated in our waters since the early 1900s. The oyster rapidly spread and naturalized all along our coastline. The beach oysters are found in quiet bays, intertidal zones, and estuaries throughout the lower Pacific Northwest. Past the upper tip of Vancouver Island, the waters appear to be too cold for this introduced species.

Oysters are best harvested in the colder months; in the summer, they are spawning and appear and taste milky. There is a thriving aquaculture industry based on tray-farmed and beach-raised oysters.

These beautiful creatures include crabs, prawns, and barnacles. They inhabit the intertidal zones of the coast. All of these organisms are members of the arthropod group of organisms and most have an exterior skeleton. They are subject to some fishing pressure due to their value as a food source and commercial harvesting activities.

Dungeness Crab (Metacarcinus magister) Dungeness crabs are some of the finest crabs in the world. They are voracious feeders in the intertidal zone and feed on a wide variety of prey including shellfish, octopus, and fish. The crabs are quite robust in the wild and have powerful pincers on their front two legs.

While a male Dungeness crab can grow to a shell width of 9 inches (23 cm), the minimum size limit for harvest in British Columbia is 6.5 inches (16.5 cm) across the maximum breadth of the shell. Most Dungeness crabs weigh between 1.5 pounds (680 g) and 3 pounds (1.4 kg). Dungeness crab is harvested in all months of the year.

Only male crabs are harvested and must be taken with baited traps but the fishery is relatively easy for anyone to start up and the crab is a relatively abundant and considered a sustainable resource. The crab prefers areas with sandy bottoms in water 30 to 150 feet (9–45 m) deep. Crabs like to hang out in bays, estuaries, inlets, and tidal streams.

Crabs from populated or industrial areas can store toxins and environmental pollutants. These often accumulate in the fatty tissue under the carapace shell. To minimize the presence of these toxins, it is advisable to clean the crab of top shell, gills, and fat before cooking.

Spot Prawn (Pandalus platyceros) There are seven commercial species of shrimp found in Canada’s west coast waters. All cold-water shrimp are fast growing, short-lived, and have a high reproductive capacity, making these species less vulnerable to fishing pressure. The spot prawn is the largest of the species and is considered one of the best prawns in the world.

Spot prawns are caught in baited traps similar to crab traps. The commercial season generally lasts from early May to mid-June. It is good practice to throw back any small prawns, female prawns with eggs, and any bycatch species you may trap by accident. The other common shrimps include the side-stripe shrimp (Pandalopsis dispar) and pink shrimp (Pandalus eous).