Chapter 1

To Confound the Course of Nature

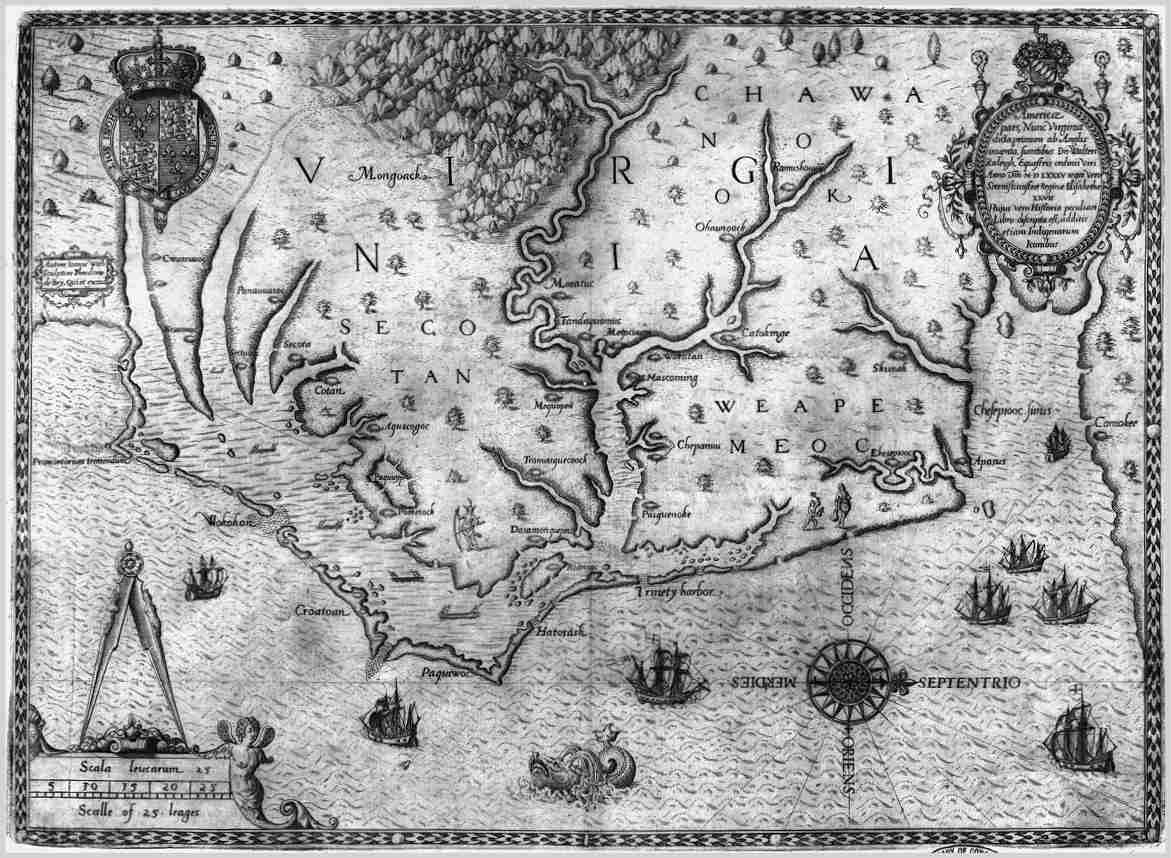

Early depictions of Virginia and the Chesapeake Bay proved influential for explorers, investors, and early colonists eager to establish themselves in the “new” world. Visual materials, like this illustrated map created by John White and reproduced by Theodor de Bry in 1590, shaped European understandings of the mid-Atlantic and its Native inhabitants.

Two people in colonial Virginia shared a bed, which was common enough in the early modern Atlantic world. In this instance, rumors spread that two servants in Warraskoyack, a small settlement across the James River from Jamestown, might have engaged in illicit sex of some kind. Two people slumbering side by side was hardly shocking in a community where the combination of scant furniture and cold winters made bed-sharing both necessary and desirable. This was different. The commotion centered on whether a domestic servant named Thomasine Hall, discovered in bed with a female servant named Besse, was in fact a man named Thomas.

The question of Hall’s bodily sex so concerned residents of the nascent settlement that several of them, unencumbered by ideas of personal privacy, forcibly examined Hall’s body for physical indications of male or female sex traits on four separate occasions. Hall is absolutely male, several people concluded. Hall is unquestionably female, others pronounced. I am both, Hall objected, refusing to identify as either a man or a woman. Pressed by local authorities to pick one sex or the other, Hall refused. So confounding was the case that it ended up before the General Court in Jamestown on March 25, 1629, after these examinations and inquiries failed to determine Hall’s sex conclusively.1 (I use they/them pronouns for Hall except when quoting primary sources, which provide key evidence about how Hall’s contemporaries interpreted Hall’s social and sexual roles.)

Hall’s experience is extraordinary, not least because the few pages of depositions and testimony within the minutes of the Virginia General Court and Council that describe these events are unlike anything else in our records of early America. This episode is also, in many ways, as much about gender—cultural expectations for a person understood as a man versus cultural expectations for a woman—as about sexuality. English Virginians held contradictory ideas about the relationship between a person’s genitals and their role as either man or woman, permitting a surprising degree of fluidity in some circumstances and demanding narrow conformity in others.

For the leaders of Warraskoyack and Jamestown, Hall’s ambiguity mattered when it became a source of discontent among other English servants, distracting them from cultivating the tobacco crops that would ensure their agricultural venture’s survival. These leaders also wanted to demonstrate the advantages of Englishness to their Indigenous neighbors and to the Spanish, French, and other European nations with colonizing projects in North America. Sexual behavior and living arrangements were among the most important indications, in their minds, of whether they were replicating the “civility” they considered indicative of English people’s superior refinement.

Their efforts to impose this order met with intense resistance from non-elite English people who had their own ideas about permissible sexual activity. The limitations that the colony’s leaders placed on servants’ bodies—in terms of the labor they had to perform and the kinds of pleasures they could seek—may have motivated some of these servants to reveal Hall’s body for what they believed it was. The disparity between law and lived experience—on topics such as gender roles, fornication (sexual intercourse with an unmarried woman), and sodomy, among others—helps us understand why Hall’s refusal to claim a single gender was urgent enough to require a court order.

The remarkable story of Thomas/Thomasine Hall introduces the themes that animate Part One of this book. Hall and the people they met in England and Virginia organized their societies as hierarchies in which class, gender, status, and, increasingly, race were supposed to determine a person’s sexual liberties. Across the lands and subjects Part One covers, those liberties expanded for white men of all classes while they constricted for most others. Yet we might see Hall’s insistent self-definition as a reminder that individuals and communities defended their distinct beliefs about the value of their own desires.

The English people who settled New England and Virginia in the seventeenth century held ideas about gender that might surprise today’s reader. Although they usually attributed one’s status as man or woman to bodily traits, there were exceptions. Under certain circumstances, a person might adopt a man’s or a woman’s role. English people in New England in the 1600s believed that a woman might become a “deputy husband” if her husband was absent for long periods of time, assuming the privileges of patriarchy in his absence. From a religious perspective, they condemned any sexual behavior outside of marriage, but they thought about sexual morality less in terms of whether the object of desire was male- or female-bodied than whether the desire originated in “unclean” lusts or contravened their ideas about social hierarchy.2

English Puritans were dissenters from the Protestant Church of England who demanded simpler styles of worship and stricter adherence to biblical law. Puritans believed that experiences of Jesus Christ’s divinity required the believer to assume a receptive role akin to how a wife was expected to behave toward her husband. When a Puritan man submitted himself to Christ, he did so as a bride. In 1651, Boston minister John Cotton asked the members of his congregation if they fantasized about spiritual sexual intercourse with Christ: “Have you a strong and hearty desire to meet him in the bed of loves, when ever you come to the Congregation, and desire you have the seeds of his grace shed abroad in your hearts, and bring forth the fruits of grace to him?” Such descriptions of spiritual ecstasy might appear profoundly homoerotic; for some of these men, it may have been. But erotic language describing Puritan men’s “penetration” by Christ’s love made sense to Puritans not because they embraced same-sex desires but because they considered the soul to be an essentially feminine entity, well suited for submission.3

These allowances for moments when a person’s gender role bore no relation to their bodily sex coexisted, however, with other fairly rigid ideas about the distinct privileges of men. “Deputy husbands” notwithstanding, English people of the early seventeenth century believed that nature had made men the superiors of women, divinely designed to provide the moral and intellectual guidance that a woman required in order to become a virtuous “good wife” who avoided dissolution and sin. Christian women bore the curse of Eve; far from the guardians of chastity that white women would later become in the popular imagination, prior to the American Revolution, they were more often considered temptresses. The minister of a church in Andover, Massachusetts, warned in the late 1720s about the “lewd and designing Woman” who led men toward “forbidden Pleasures.”4

Nor did a gentleman and a male-bodied servant share the privileges of patriarchy equally. Indentured servitude was the primary labor system in 1620s English settlements in Virginia. These servants, who made up more than half of the white immigrants to English settlements in North America before 1750, exchanged between four and seven years of unpaid labor for the cost of passage across the Atlantic Ocean and room and board upon arrival. Elites tried to control their servants’ private lives. Many indentured servants signed contracts that prohibited them from marrying (or required that they first obtain a master or mistress’s permission), which left them no legal means of having sex. But one of the challenges for elites in seventeenth-century Virginia was that the distinctions of social rank were far more dynamic there than in England. A male servant in a North American colony who completed his term of indenture had what, for the time, was an unprecedented opportunity to purchase a farm and even, in a few instances, acquire wealth befitting a gentleman. If male, then Hall might one day become a patriarch of his own household, the governor of a miniature state who was expected to keep his dependents in line and maintain the family’s reputation. But if female, Hall would always suffer from the irrational passions people at the time (including women) thought all women possessed, traits that made the governance of a wiser man—whether father, husband, or master—both necessary and good.5

A preoccupation with demonstrating English and Christian superiority over all other cultures informed these ideas about gender and sexual behavior. English travelers to West Africa alternately marveled at the extraordinary beauty of the people they encountered and described those people as less than human, their “heathen” bodies better suited to brutal labor conditions than “Christian” people’s were. Europeans depicted African women’s breasts as startlingly distended, like an animal’s, a savage counterpart to the supposedly high-breasted figure of European women. Englishman William Towerson’s account of his travels to Guinea in West Africa in 1555 conferred beast-like qualities on the women’s breasts, “which in the most part be very foule and long, hanging downe low like the udder of a goate.” However physiologically impossible, Towerson’s vivid account helped make theories about supposed distinctions of race appear real, rooted in observations of the “natural” world.6

Servants such as Hall and Besse labored alongside some captive Native people and a small but growing population of free and enslaved Africans in Virginia. Spanish and Portuguese traders had been purchasing and selling enslaved people from major ports along the West African coast since the 1400s. As early as 1513, enslaved people from Africa likely accompanied Spanish explorers who traveled north from Mexico to the Pacific coast; in 1526, Spanish soldiers forced one hundred enslaved people to help them create a colony in present-day South Carolina. Europeans also enslaved Indigenous people they encountered in the Americas. Some white men proudly described how they captured Indigenous women as rewards for their journeys, conflating the Indigenous women’s relative nakedness with an invitation for sex. More than 700,000 Africans were enslaved and sold on the far side of the Atlantic Ocean, primarily in the Caribbean and South America, between 1580 and 1640. Dutch and English slave ships soon outnumbered those bearing Spanish or Portuguese flags. In 1625, only 23 Africans lived among 1,200 English people in Virginia. (By 1640, those numbers had increased to 300 Africans and 15,000 English Virginians. The number of enslaved Africans in the English colonies rose precipitously after 1660.)7

Perhaps more immediately, the English residents of Warraskoyack contended with Native people whose land and resources they had claimed for themselves. That reality contrasted with widely circulated sexual fantasies about America’s submission to the wills of English men. English travelers waxed eloquent about the sexual possibilities of travel to the New World; poet John Donne described America as a woman he undressed, as he “discovered” her in a conquest of her “virgin” land. Those erotic metaphors gave many English people a false sense of entitlement to Native people’s lands, ones that they would possess as a man possessed a woman.8

At the same time, many English settlers described Native North Americans as “savages” who did not deserve the lands they occupied. For proof, they depicted Native men as simultaneously promiscuous leches and impotent failures. Correct sexual behavior became an essential means of distinguishing Christian from heathen, civilized from savage, and white from “red” or “black.” The English feared that sexual intimacy with Indigenous or African people would lead them into the savagery they associated with all non-English people. For English elites who wanted to reestablish civil society in the New World, proper sexual relations would be a measure of their success.9

It is no wonder, then, that Thomas/Thomasine Hall’s refusal to define themself as either man or woman confounded their neighbors and local authorities. At stake were some of the most fundamental assumptions that English people of the early seventeenth century held about what distinguished one person from another and determined their place in society.

In or about 1603, a person who would be christened Thomasine Hall was born in England. Early on, Hall assumed male or female gender according to their circumstances. At age twelve, Hall went to live with an aunt in London and learned skilled women’s work. Hall first dressed as a man about ten years later, when they enlisted in the English Army. Hall’s brother had recently served in England’s 1625 expedition in Cadiz (one of the deadliest battles in what became a five-year English–Spanish war), and Hall seems to have wanted to follow in their brother’s footsteps. To do so, Hall “cut of his heire and Changed his apparell into the fashion of man,” presenting for duty as a twenty-two-year-old soldier named Thomas Hall. After a year’s service in France, Hall sailed back to Plymouth, England. Once again attired in women’s clothing, Hall made a living sewing lace, a woman’s occupation. In 1627, Hall again wore men’s clothing aboard the ship that carried them to Virginia.

The small settlement of Warraskoyack was named for the Algonkian village whose residents the English had forced out, after a series of attacks by the Powhatan people killed as much as one-third of the English population in Virginia. The celebrated marriage between the Powhatan chief’s daughter, whom the English called Pocahontas, and English captain John Rolfe had forged a temporary truce in 1615; the couple traveled to London with their infant son and met members of the royal family. Their story ended tragically in Pocahontas’s death aboard a ship for the return voyage in 1617. As warfare surrounded Jamestown, English migration to Virginia stalled.10

Thomasine Hall would have been one of a small number of English women in the labor-intensive tobacco plantations of Virginia. Warraskoyack, established in 1622, included two major tobacco-farming plantations. Women often worked in tobacco fields and factories, and they also typically knew more than men did about gardening, weaving, and other productive tasks that English people considered women’s work.11

The shortage of English women in the Chesapeake was sufficiently dire that the Virginia Company rounded up and shipped over women who could provide male colonizers with sexual pleasure, domestic labor, and, through their reproductive labors, English children. The company’s treasurer, Sir Edwin Sandys, pledged to find a “fit hundredth” of “maids young and uncorrupt to make wifes to the inhabitants and by that meanes to make the men there more settled.” All told, between 1620 and 1624, the Virginia Company sent more than two hundred English women to Jamestown, each valued at £150 that their prospective husbands would repay to cover the cost of their transport to the colony. Even so, in 1624, adult women totaled just 230 of the 1,250 Europeans living in Virginia.12

Soon after disembarking in Virginia, Hall became a maidservant in the home of John and Jane Tyos. The well-ordered household, the English believed, was emblematic of their civility and thus essential to their demonstration of superiority over both their Indigenous neighbors and other Europeans venturing to the New World. A skilled seamstress, Hall likely engaged in a variety of arduous tasks, including food production and preparation, hauling water for cooking and cleaning, laundering, and the making of candles, soaps, clothing, and other material goods that aided the settlement’s continuance. Presenting as a woman, Hall was a useful domestic servant in the Tyos household. Tyos, as patriarch, benefitted from the labors of an indentured servant such as Hall but was also expected to keep his dependents out of trouble.13

The commotion in Warraskoyack about whether Hall was a female servant began sometime in late 1628 or early 1629. A man known as Mr. Stacy, about whom little else is recorded, seems to have raised the alarm over the ambiguity surrounding Hall’s sex, but women in the community were the first to investigate the matter. After Mr. Stacy told other English residents of Warraskoyack that Hall was “as hee thought a man and woeman,” rather than a clearly female servant, women in the community exercised their authority over women’s bodies to force an examination of Hall’s genitals. When English communities or courts needed intimate knowledge about a person’s body, community members of the same sex obtained it. Women more broadly had a degree of power in matters related to female sexuality; nearly all midwives at the time were women, recognized as experts on matters related to reproductive sex. Because Tyos believed his servant to be a woman, three women, Alice Longe, Dorothye Rodes, and Barbara Hall, conducted the first of several inspections of Hall’s body.14

The surviving record gives no indication that Hall resisted, but as a servant, they had limited power to refuse. These were surely, at the very least, uncomfortable if not deeply upsetting events for them. The women reached an unambiguous conclusion: they “found (as they then said) that hee was a man.” John Tyos, meanwhile, “swore the said Hall was a woeman.” Was Hall male or female? What norms or laws would govern the labor or the sexual behavior of a person who was both man and woman?

All of this commotion about Hall’s ambiguity brought the issue to the attention of Captain Nathaniel Basse. He was Warraskoyack’s unofficial leader and the proprietor of the newest tobacco plantation, determined to earn a profit from tobacco despite the colony’s recent losses. Basse had served in Virginia’s House of Burgesses and would soon be a member of the Governor’s Council of Virginia. His high military rank and roles in colonial government endowed him with civil stature and authority over servants such as Hall.15

As the nominal leader of the settlement, Basse asked Hall directly what sex they were. Hall “replyed that hee was both.” Elaborating, Hall explained that they had both male and female genitalia. The surviving minutes of the General Court were partially destroyed, but the extant text includes Hall’s explanation that while unable to get an erection (“hee had not the use of the mans parte”), Hall’s body included “a peece of fleshe growing at the [missing section] belly as bigg as the top of his little finger, [an] inch longe” and “a peece of an hole.” Perhaps Hall had a larger-than-average clitoris and a small or truncated vagina. Hall’s description of male impotence suggested an awareness of the English common-law requirement of sexual consummation for a valid marriage. If that was the case, Hall would have been exempted from the expectation to become a husband.16

Early twenty-first century Americans use words like “transgender” to describe people who have a fluid relationship to gender or whose gender expression is different from the norms associated with the sex assigned to them at birth. Another useful term is “intersex,” employed to account for a wide variety of anatomical, hormonal, and chromosomal differences that affect 1 of every 200 people whose bodies do not conform to a simple male/female binary. Although neither Hall nor Hall’s contemporaries knew these words, early modern people in England and in North America grappled with the possibility that sex was a fluid or changeable trait. “Hermaphrodites” and “androgynes” had populated European legal texts and poetry since 200 CE. Early modern people recognized that some people were born with ambiguous genitalia, but they typically insisted that a person choose one gender—and stick to it. In their refusal to align with a single gender, Hall was unusual.17

An elongated clitoris is often related to an intersex condition known today as congenital adrenal hyperplasia, which occurs when a person with XX chromosomes produces an atypically large amount of androgen, the hormone that generates male sex characteristics. Hall’s contemporaries of course lacked knowledge of either chromosomes or endocrinology, relying instead on their visual observations of Hall’s body and their preexisting assumptions about which traits made someone a man or a woman. Basse overruled the assertions of the women who examined Hall’s body and ordered that Hall wear “woemens apparell.” Respectful enough of authority to think Basse might know more than they did, Longe, Rodes, and Barbara Hall second-guessed their initial determination. They “stood in doubte of what they had formerly affirmed.”18

The community’s ambivalence about Hall’s bodily sex persisted, despite Basse’s public pronouncement of Hall’s femaleness. Longe, Rodes, and Barbara Hall decided they must take a second look to see if their earlier conclusion was an error. John Atkins had recently purchased Hall’s term of indenture from Tyos, acquiring a maidservant called Thomasine. The three curious women entered the Atkins home and examined Hall while Hall slept. Their search reaffirmed their initial observation: “and then allsoe [they] found the said Hall to bee a man.” The women urged Atkins to see for himself, but he refused to inspect his servant’s body, explaining that Hall was “seeming to starre as if shee had beene awake.” Was Hall lying inert but fully conscious during this second examination? Did Hall stare at Atkins as a challenge or as an appeal for help? (Or did Hall sleep with their eyes open?)

A week later, Longe, Rodes, and Barbara Hall returned to the Atkins home, now with two more women, to conduct a third inspection of Hall’s body. Atkins did not stay away this time and agreed with the five women that his servant was male. He ordered Hall to wear men’s clothing, using his authority as head of household temporarily to invalidate Basse’s earlier ruling.

A determination of whether Hall was a man or a woman became more urgent after a rumor circulated in early 1629 that Hall “did ly wth a maid of Mr Richard Bennets called greate Besse.” Longe, who had already searched Hall’s body on three occasions, may have spread this rumor. She said the source of the gossip was one of Tyos’s servants. Greate Besse was likely an indentured servant just as Hall was. Had T. Hall and Greate Besse committed the crime of fornication?

Fornication was prosecuted throughout the English colonies in North America. The devout Christians who settled in Virginia and New England created legal systems that combined English common law, which stressed the value of patriarchal household government, and biblical injunctions against sexual relations outside of marriage. In the first century of English settlement, courts from New England to the Chesapeake not only charged unmarried people with fornication but even brought fornication charges against married couples retroactively if the bride gave birth to a full-term child in eight months or less after the wedding date. Ministers often led such couples before their assembled congregation to beg forgiveness for committing both a sin and a crime.

White women faced prosecution for illicit sex more often than white men did. Female fornicators also endured far greater social ostracism, even in cases involving sex with a minor or “ravishment.” In 1677, a servant named Mary Manning tried to avoid this stigma when she asked the court of New Castle, Delaware, to mercifully “Cleare hur from the threats and future scandall” of her association with Jeremy Farrington, who had “deluded her from [her employer]” and falsely promised to marry her. The court ruled in her favor. More often, even when female servants alleged coercion, they rarely succeeded in convincing local justices to absolve them of the charge of fornication.19

This aggressive pursuit of fornication charges, handed down by high-ranking men, infuriated non-elite Anglo-Americans. They believed that a betrothal rather than formal marriage was the point at which sex became permissible. Non-elites not only made allowances for premarital sex, they recognized couples as married irrespective of a minister’s blessing or legal contract. This culture of informal marriage survived in many regions of the American South well into the 1700s, eliciting a steady stream of consternation from Protestant ministers who bemoaned generations of children they believed had been born into sin. Servants in Warraskoyack knew the penalties for disobeying their masters but also sustained their own ideas about legitimate sexual behavior.20

Greate Besse, whose opinion of her involvement with Hall was apparently not pursued by the officials who recorded testimony for the case, was both the legal dependent of her employer and a member of his household. Her employer (whom the surviving records do not identify) would have been expected to maintain control of his dependents—wives, children, indentured servants, and enslaved laborers—lest he appear insufficiently patriarchal. Because colonial governments in New England as well as in the Chesapeake were limited and weak, they relied on male heads of household to govern judiciously. Property-owning families proved to be especially adept at protecting their own relatives from negative legal outcomes; single, indentured, and enslaved women were more exposed. (Domestic leadership was especially important because the English insisted that everyone live within households; given the paucity of English women in the Chesapeake until much later in the seventeenth century, this expectation resulted in numerous homes comprised solely of men.)21

English residents of Warraskoyack would not have assumed that a man named Thomas coerced Besse into bed. They viewed women as the “lustier” sex and denigrated servant women as “wenches” with untamed erotic impulses. Given their understandings of how the reproductive system worked, men of the time would have not only acknowledged women’s capacity for erotic pleasure but, presumably, often actively pursued it. Both men and women emitted a seed during orgasm, the thinking went, the combination of which created the potential for human life. A still-trusted scientific authority had written in 1583, “unwilling copulation for the most part is vain and barren: for love causeth conception.” That theory nevertheless worked against women who became pregnant because of an assault. When sixteen-year-old Priscilla Willson was charged with fornication in 1683 in Essex County, Massachusetts, members of the community testified that Samuel Appleton, a wealthy merchant, had forced himself on her. Their attempts to defend Willson failed because she became pregnant, which the local authorities interpreted as evidence that she had enjoyed the sexual encounter.22

A child born out of wedlock to an indentured servant such as Greate Besse would have created additional complications. Colonial authorities in Virginia appeared less worried about sexual sin than the financial costs of a child born to an unwed mother. Any potential child would impair the mother’s ability to work while she recovered from childbirth and burden her employer with additional expenses. One of the ways English colonial settlements tried to recoup those losses was to require the father to pay damages to the woman’s employer. Local governments attempted to identify the father (often by interrogating the woman during the most intense stages of childbirth). Men of lower status were more likely to be found guilty of bastardy and ordered to pay child support. Servant women who bore a “bastard” faced the forced indenture of their child and had one or two years added to their own terms of indenture. The more fortunate among them might marry their employers, or another landowner might pay the balance of a pregnant servant’s indenture and marry her. Southern English colonies prosecuted bastardy more often than fornication or any other sex-related crime. By the 1670s, a woman convicted of bastardy had even more years of service added to her indenture, and her sexual partner owed steeper monetary damages to her employer.23

The situation in Warraskoyack in 1628 and 1629 was perhaps less about profit than privilege: Was Hall, male-bodied but female-attired, getting away with sexual play otherwise forbidden to indentured servants toiling in Virginia? Two young men in particular insisted on knowing whether Hall was male or female. Roger Rodes and Francis England worked on the same plantations as Hall did. (Perhaps Roger was the husband of Dorothy.) Rodes and England “laid hands upon the said Hall” and “threw the said Hall on his backe” to determine the nature of Hall’s genitals for themselves. England thrust his hands into Hall’s clothing and “pulled out [Hall’s] members whereby it appeared that hee was a perfect man.” England demanded that Hall explain why they wore women’s clothing if their body indicated male sex.

Hall answered that they wore women’s clothing “to gett a bitt for my Catt.” The precise meaning of that phrase has vexed historians. Perhaps it meant to “earn a living.” Or perhaps, given that “bit” was an early modern English slang for a morsel of food, women’s attire improved Hall’s chances while begging for something to eat. The time Hall had spent in France suggests a more subtle, humorous, and defiant assertion: a too-literal translation of the French slang, pour avoir une bite pour mon chat, or “to get a penis for my cunt.” After enduring this fourth bodily search, Hall apparently asserted an erotic playfulness in response to England and Rodes’s physical and verbal intrusions.24

The issue now had clear legal repercussions and went before the General Court in Jamestown, the colony’s highest judicial authority.

The commotion over Hall’s bodily sex—and possible sexual misbehavior—occurred as English people in North America were beginning to argue that a person’s status depended not only on their social position as master or servant but on whether they traced their ancestry to England, America, or Africa. Enslaved Africans, captive Indians, and indentured servants lived under varying forms of unfreedom in the North American colonies. On farms and in towns, enslaved Africans worked alongside indentured servants, and some even lived with one another. In Hall’s time, an African-born woman known as Mary and her African husband, Antonio, earned their freedom and became property owners; Mary’s children were free. In the earliest years of English settlement in the Chesapeake and New England, it was not yet clear that slavery was lifelong or that it was a status that an enslaved woman’s children inherited. Mixed-race unions thus did not initially raise questions about whether their child would be enslaved.25

Instead, colonial English courts at first handled fornication cases involving combinations of English, Native, and African people according to the same laws against fornication that ensnared indentured servants who had sex with one another or with a free English person. Whether enslaved or a servant, the man convicted of fornication was typically whipped and fined. But very soon, the calcifying rules of Atlantic slavery meant that an African-descended man found guilty of fornication might be sold to compensate his sexual partner’s master. The children of these unions suffered: colonial courts often demanded that “mulatto” children born to convicted fornicators serve an exceptionally onerous thirty-year indenture to compensate for the cost of their upbringing. In Virginia, these revised fornication laws also reflected English colonists’ fears about sex between baptized Christians (mostly members of the Church of England) and “heathen” Africans or Indians. Religion, like race, became yet another marker of inherited difference.26

More than thirty years after Hall’s interrogation, as England’s participation in the Atlantic slave trade expanded, a 1662 law in Virginia, for the first time, defined slavery as a perpetual inheritance, passed down from mother to child. That law also made any sexual contact between an African and English person illegal; prior to 1662, a free Black man and a free English woman could legally marry in Virginia. Leaders of the English colonies in North America wanted to prevent English indentured servants, who would attain the status of “free” people once they served their terms, from creating households or producing children with enslaved Africans. A 1664 law in Maryland scolded “diverse freeborn Englishwomen,” most likely indentured servants, who “to the disgrace of our Nation doe intermarry with negro slaves.” The law stipulated that any white woman who married an enslaved man would become enslaved to her husband’s master. In 1692, Maryland’s legislature spelled out additional punishments for interracial fornication, indenturing for seven years any woman who gave birth to a mixed-race child of an enslaved man; if the child’s father was a free Black man, then the father, too, would serve seven years’ indenture.27

Eventually, English laws and the French Code Noir, issued by the French government in 1685 for their colonies in the Caribbean and adapted for Louisiana in 1724, quoted the Latin principle of partus sequitur ventrem—“status follows womb.” In societies otherwise organized around patriarchal inheritance, this principle assigned a child’s status—free or enslaved—based on the condition of their mother, her identity reduced to the “womb” that birthed them. Slavery thus marked African women as a distinct kind of maternal being, a difference that was intended to ensure the enslavers’ control of their offspring.28

An official determination that Hall was a man might have subjected Hall or Besse to fornication charges, but criminal allegations were far less likely if the court concluded that Hall was female. Sex between two female-bodied people or two male-bodied people was both a sin and a capital crime according to English faith and law, but it was rarely prosecuted. For resource-strapped English settlers, it did not present the immediate financial peril of a fatherless child or a disobedient servant.

Surviving records document only two cases of women punished for sex with women in the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries in the English colonies of North America. In 1642, the Essex County quarterly court in Massachusetts sentenced Elizabeth Johnson to be whipped and fined for “unseemly practices betwixt her and another maid.” In 1649, Mary Hammon and Sara Norman, from Yarmouth in Plymouth Colony, were convicted of “leude behavior each with [the] other upon a bed.” Norman was also charged with “divers Lasivious speeches,” suggesting that she had not only acted but spoken immodestly. While Norman was sentenced to publicly acknowledge “her unchast behavior,” Hammon was not punished. New Haven Colony, which was strictly governed according to biblical law, was the only colonial jurisdiction to outlaw sex between women. When the Connecticut Colony absorbed New Haven in 1664, Connecticut’s laws took precedence, and sex between women was nowhere illegal—or, for that matter, legally defined—in the English colonies of North America.29

“Sodomy,” generally defined in English and Dutch colonial law as penetrative sex between men, was a capital crime understood to be a serious violation of God’s commandments, but it, too, was seldom prosecuted. (New Haven Colony, yet again the exception, identified sodomy as anal penetration of a man or a woman.) Men convicted of sodomy rarely received the death penalty. Plymouth Colony’s first sodomy trial, in 1636, found two men guilty but sentenced them to whippings and branding rather than death. The only executions for sodomy in New England occurred in New Haven Colony. The few colonial sodomy cases that resulted in the death penalty involved not simply the crime of sodomy but the outrage of forced sex—of penetration without consent or otherwise in violation of acceptable norms of adult sexual interactions.30

Yet in Windsor, Connecticut, half a dozen young men complained over the course of thirty years about unwanted sexual advances from Nicholas Sension, a wealthy resident, before authorities finally charged that he “most wickedly committed, or at least attempted, that horrible sin of sodomy” in 1677. The criminal case might never have commenced at all if Sension hadn’t sued one of his former servants, Daniel Saxton, for defamation. Saxton claimed that Sension had tried to force himself on him. The court determined that Sension’s accusation against Saxton was meritless and that Sension in fact deserved to stand trial. Witnesses recounted decades of Sension’s sexual abuse. “I was in the mill house and Nicholas Sension was with me, and he took me and threw me on the chest, and took hold of my privy parts”; “Sension came to me with his yard or member erected in his hands, and desired me to lie on my belly, and strove with me.” A jury comprised of Sension’s peers—white “freemen” who could vote and hold office—convicted him of attempted sodomy. They sentenced him to stand under the town’s gallows with a rope around his neck, be whipped, and pay fines to cover court costs and ensure future good behavior. He also forfeited his rights as a freeman.31

Still, the fact that there was a conviction at all seems due to Sension’s apparent assault of his sexual partners. Indeed, the complaints against Sension remind us both that violence—sexual and otherwise—suffused the life experiences of these colonial settlers and that these individuals were outraged by certain kinds of assault.

Laws governing interracial sex in the English colonies, meanwhile, grew stricter as the enslaved population increased in the second half of the seventeenth century. In Virginia, a 1691 statute that outlawed interracial marriage not only introduced the word “white” into Virginia’s legal code for the first time but legislated the unequal treatment of women. “English or other white women” were now prohibited from marrying or fornicating with “negroes, mulattoes, and Indians,” in order to prevent what legislators derisively called the “abominable mixture and spurious issue” of those unions. The number of women and men arriving in Virginia as indentured servants had declined by the 1680s and 1690s; lawmakers perhaps hoped to keep the white women of the colony for themselves. At the same time, the law made no mention of sex between white men and Black or Indian women; the sexual privileges of white men were becoming clearer, even as they went unspoken.32

In 1629, when the inability of Basse and other residents of Warraskoyack to settle the question of Hall’s sex brought the case to the General Court in Jamestown, the only matter the court addressed was whether Hall was a man or a woman. Perhaps some members of the court additionally pondered whether Hall, a man, committed the crime of fornication with Besse, or if Hall, a woman, engaged with Besse in other “lewd” acts. If so, they did not leave a record of those concerns. What emerged clearly was a community mobilized to resolve the perceived social chaos that followed from sexual ambiguity.

The General Court’s ruling was astonishing, and, as far as we know, unique. The governor and his council concluded that Hall was both male and female. The court effectively created a new gender category for Hall, but in doing so it mocked Hall’s identity. Likely hoping to prevent Hall’s ambiguity from leading to illicit sexual behaviors, the court punished Hall by requiring them to dress as two sexes at once: “it shall bee published in the plantation where the said Hall lyveth that hee is a man and a woeman, that all the Inhabitants there may take notice thereof and that hee shall goe Clothed in mans apparel, only his head to bee attired in a Coyfe and Crosecloth [female headcovering] wth an Apron before him.”33

In the end, Hall’s sentence was a kind of sartorial humiliation, a decree to wear men’s clothing with women’s accessories. Cross-dressing itself would not become a crime in any of the English colonies until the end of the seventeenth century. Rather, in a society where attire signaled a person’s place in the social order, Hall’s punishment emphasized dislocation. As both man and woman, Hall was legally unsexed: they could not marry and thus could not have licit sexual relations at all.

Any attempt to determine the “real” sex or gender identity of an individual such as Hall risks imposing a twenty-first-century frame on people who lived in a society far different from our own. Hall defined themself as both male and female centuries before such words as “nonbinary,” “intersex,” or “transgender” might have matched their self-understanding. Yet until the General Court sentenced Hall to wear both male and female attire, Hall consistently self-presented as one sex, perhaps reflecting an awareness that while they considered themself “both,” they moved within a social world that permitted only one or the other.

The inventiveness and defiance in Hall’s expression of their gender hints at how people at the time thought about the naturalness of sex. The women who inspected Hall’s body made the case that genitals determined gender: a person with a penis was a man. At various moments, Hall’s employers offered more ambivalent appraisals of their servant’s sexual identity. They may have cared less about what was “natural” than what was useful to their risky experiments in tobacco farming. Hall chose to live outside these expectations and define gender on their own terms.

Two pages of a court proceeding comprise the entirety of the historical record about T. Hall. Did they spend their remaining years wearing both male and female clothing as ordered by the court? Did Hall leave Warraskoyack—sail north to Plymouth or New Haven, south to Barbados, or even east on a return trip to England—to regain control over their gender? Perhaps Hall grew acquainted with one of the Algonquian-speaking peoples of the Chesapeake or survived an overland journey south to the Carolinas, yet unknown to English people but home to dozens of Indigenous nations. That may be a fantastical notion. Yet there—or farther west, among the Pueblo of New Mexico, where our story continues—Hall would have encountered Native communities that valued and accepted a two-spirit person.