Chapter 2

Sacred Possessions

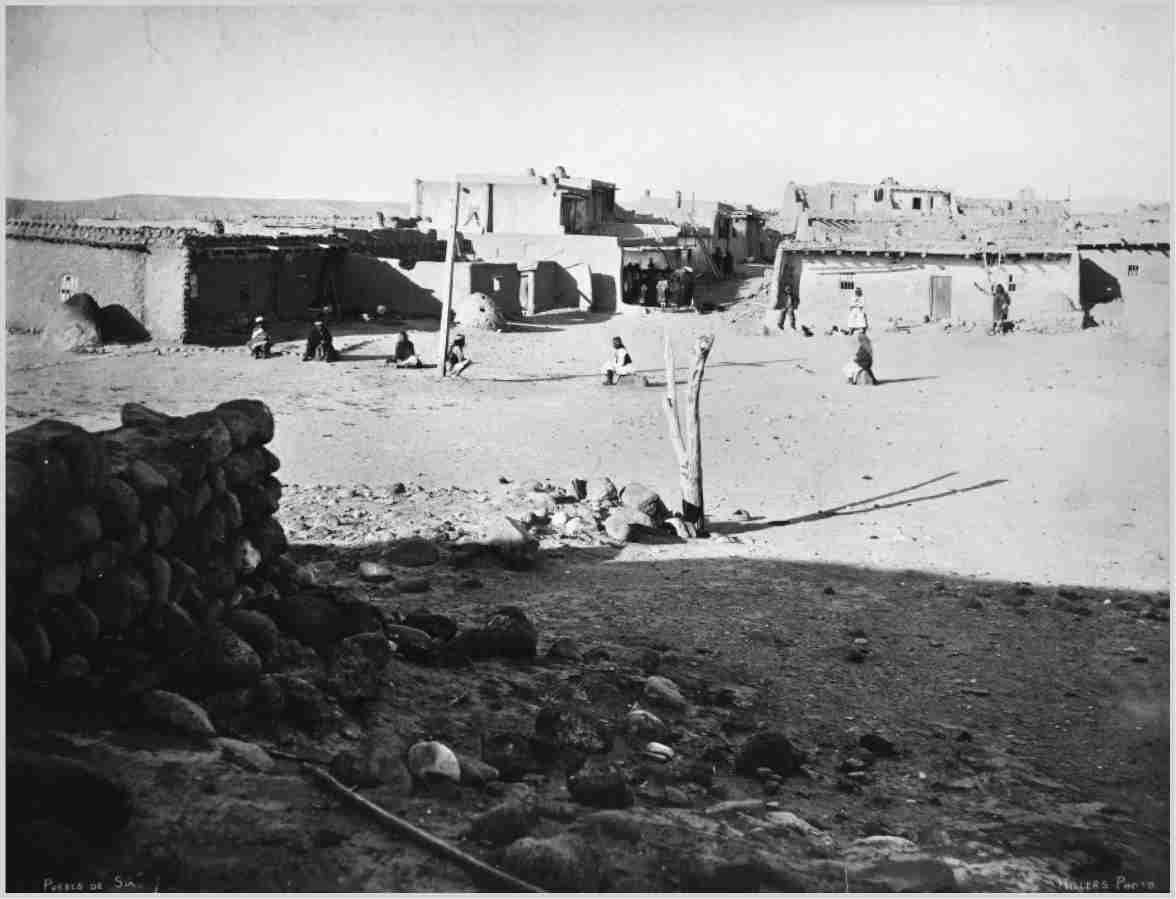

Zía Pueblo people believed in a recurring, repeating life cycle that began when the gods gave them fire and taught them to build their houses. Perhaps it was inside a two- or three-story adobe home like those pictured here that Juana Hurtado learned about the origins of her people from her mother, a Zía Pueblo woman.

Juana Hurtado was still a child the day in 1680 that Diné (Navajo) warriors on horseback stormed her father’s ranch in what is today New Mexico. Documents and archaeological evidence contain a host of details about these events, but how they unfolded from the perspective of a child is a question about which we can only speculate. Perhaps the drumbeat of hooves against packed dirt sent Juana racing to the house from a garden patch she tended. A bucket of water from the Jemez River thrown aside to free her small legs to run faster, an armload of firewood discarded along the path: our imaginations crave details from the ungenerous historical record of the 1680 attack.

Maybe seven-year-old Juana cried for her mother, a Pueblo woman whose brother, Juan Checaye, was the governor of Zía Pueblo (a Pueblo village). Juana’s mother would have reached adulthood having absorbed stories about the origins of her people, stories in which sexual desires, reproduction, nature, and the spirit world wove a web of connection with the ancestors. Franciscan friars, who established missions throughout New Mexico in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, would have tried to teach Juana’s mother that anything other than marital fidelity according to Roman Catholic teaching would condemn her soul to hell. In 1673, this woman came to reside in the home of Capt. Andres Hurtado, likely as a servant, and bore Juana, one of the hundreds of coyotas—people of mixed Native-Spanish parentage—in seventeenth-century New Mexico.

Or Juana might have called out to her father, Captain Hurtado. He was an encomendero, a Spanish man who had been granted land in the viceroyalty of New Spain from colonial authorities in Mexico as a reward for his contributions to their recent military conquests. The Crown’s gift permitted him, as far as the Spanish were concerned, to force Native people to work that land. He would likely also have seen Juana’s mother as another sort of reward to which his birth entitled him. He had been raised in a culture of machismo that understood the control of women’s sexuality as a demonstration of a man’s status. Those ideas taught Spanish men to associate their personal honor with their ability to exert power over other people. In New Mexico, a Spanish man might consider both his military victories over Indigenous people and his control over women in his household as proof of his masculine strength.1

Everything about young Juana’s life to that moment had taught her to understand the threat of angry men on horseback. But a child, even a clever one, cannot outrun horses or defend herself against a man with a gun. Grabbed from the yard or seized inside her home, Juana became a captive among the Diné, ancestral enemies of her mother’s people. Her life followed a common, if violence-ridden pattern, shaped by the ongoing skirmishes among the Pueblo, Diné, and Spanish. Yet she would one day become a wealthy, sexually defiant landowner. She would be known as Juana la Coyota, an appellation that recognized not only her mixed birth but also her authority.2

Sacred stories of Pueblo sexuality were an inheritance that a Pueblo mother could pass down to her daughter. Juana’s Pueblo kin traced their origins to a time when gods gave them fire and taught them to build their houses. They told the story of the Corn Mother, an ancestor born under the earth whose own children became their foremothers and whose protection enabled them to grow the harvests that sustained them. Seeds from the Corn Mother symbolized the female power of generation; the Hopi Pueblo word posumi translated both as corn seed and as nubile woman.3

Rituals surrounding birth emphasized the connections between human sexuality and natural abundance. Women of the Zuni tribe, a subset of the Pueblo people, celebrated the birth of a daughter by placing a gourd filled with seeds over her vulva and praying that she would grow to have large and fruitful sex organs. They greeted the birth of a boy by sprinkling his penis with water and praying that it would remain small. Pueblo men who loathed that tradition’s emphasis on women’s dominant role in procreation engaged in rituals of their own. They wore immense artificial penises carved out of wood while singing, one Hopi man explained, “about the penis being the thing that made the women happy.”4

Pueblo communities taught that pleasure pervaded the natural world and flowed through their benevolent spirits. Neither the body nor sexual conversation were shameful. In warmer weather, both women and men typically wore small coverings over their genitals but did not cover their chests. They observed evidence of sexuality in nature—seeds and rain, earth and sky—and believed that human sexuality reflected it. Sexual intercourse forged cosmic harmony, uniting and balancing the masculine sky and the feminine earth. Some Pueblo people performed a ceremony at the solstice that concluded with intercourse.5

Mutual exchange and kinship, not hierarchy, shaped Pueblo ideas about gender and sexuality. Their beliefs emphasized contrasts between male and female sexual energies, differences that structured everything from the division of labor within and beyond the pueblo to rituals for healing and warfare. As the complement to men’s role as warriors and hunters, women could, through their sexual energies, pacify the spirits of a slain foe by symbolically enacting sexual intercourse on the scalps of vanquished enemies, as they did with the hides of deer that men of the community had hunted. Intercourse between a foreign man and a Pueblo woman was also often understood as a means for women’s erotic power to mollify antagonistic spirits or to forge new trade or diplomatic bonds. In the Pueblo worldview, women’s sexual desires were not shameful. They were considered essential for community cohesion and relationships with outsiders.6

Indigenous marriage practices throughout the continent reflected values of kinship and reciprocity. Marriage among the Pueblo, as among many Indigenous North Americans, required only mutual commitment rather than a priest’s or an elder’s blessing. Young Pueblos freely engaged in premarital sex, with girls and women using herbal contraceptives and practicing abortion. Most Indigenous families were “matrifocal”: a new bride brought her husband home to live among her people rather than his. Kinship bonds stretched vertically through multiple generations and horizontally to include female kin and their households. In 1601, an observer noted that Pueblo people “make agreements among themselves and live together as long as they want to, and when the woman takes a notion, she looks for another husband and the man for another wife.” A Zuni wife needed only to leave her husband’s belongings outside her dwelling to indicate that she no longer considered him her spouse.7

Pueblo women prized their sexuality as the source of future generations of their people and of their own pleasure. If married, sex was a wife’s gift to her husband to acknowledge his contributions to her mother’s household. If not married, then the woman expected a man she had sex with to give her something in return, perhaps a blanket or salt or hides. Throughout North America, Europeans repeatedly misinterpreted these and similar practices as evidence of Indigenous prostitution.8

Pueblo men’s power came from their expansive connections to the world beyond their homes and villages: agriculture, hunting, and warfare. (Women supervised agriculture in many other Indigenous cultures.) Pueblo women were kept out of men’s domains, just as men were excluded from the management of food storage or family life. Men abstained from sex for four days before and after warfare or hunting to renew the vitality of their masculine powers. A medicine man similarly avoided sex (as well as salt and meat) for four days before attempting to cure a disease.9

The clear lines between men’s and women’s roles nevertheless coexisted with an acceptance of individuals who contained both male and female essence. At least 155 American Indian and Alaska Native nations had members of their communities who had a “two-spirit” identity, such as the Diné nádleehí, the Lakota winkte, and the Sauk and Fox aya’kwa. The Northern Algonquin word niizh manitoag connotes a person who possesses a combination of masculine and feminine qualities. A Jesuit missionary living among Illinois and Nadouessi people near Lake Superior observed boys who “while still young, assume the garb of women, and retain it throughout their lives.” Some two-spirit people worked alongside women at tasks associated with women’s work, such as caring for the sick and injured, weaving, food production, and agriculture. The Chumash, a tribe in California, celebrated individuals they called joyas as the consummate combination of male and female natures, imbued with spiritual gifts and worthy, in some cases, of marriage to a chief as a second wife. The prevalence of these two-spirit people fascinated and often confused white colonists, who complained that Native American people were inveterate “sodomites.”10

Gender transition among children assigned female at birth occurred less often, but parents in some cases raised these children to perform masculine roles such as hunting and warfare. Some of the earliest records from Spanish travelers in what are today Florida and New Mexico noted the power of female chiefs and warriors. These individuals seem to have married other women.11

Juana’s mother was claimed by Captain Hurtado as Spanish soldiers asserted control over New Mexican towns, but sexual intimacies between Indigenous women and European men across North America often occurred on terms that Native women set. Throughout the 1600s and 1700s, many Native nations retained their culture’s sexual values, despite European desires to change them. This was partly due to their sheer numbers: one historian describes seventeenth-century North America as “a vast Indigenous ocean speckled with tiny European islands.” Indigenous people’s control of the trade routes upon which Europeans depended also allowed them to maintain considerable autonomy long after Europeans arrived in North America.12

Some Native women welcomed French and English traders into their homes. It was a familiar economic and political strategy among the Indigenous people of North America, even before the arrival of white colonists. These sexual relationships expanded Indigenous kinship networks. The Caddoan people of Louisiana and eastern Texas had long approached intermarriage as a political and economic strategy, using it to consolidate three American Indian confederacies in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The French men who began to arrive in the early eighteenth century struck Caddoans as another people who might become allies in war and partners in their established commerce in horses, furs, and human captives. By helping traders survive in a strange land, these relationships sustained European financial ventures.13

In the Northeast and Great Lakes region, cross-cultural sex became essential to the success of the monumentally lucrative fur trade through which hundreds of thousands of pounds of beaver pelts became moccasins, leather belts, and other luxuries for European and American consumers. French and English men who married Indian women typically formed households according to Indigenous practices, sealing their bonds by smoking a calumet. Colonial administrators and missionaries initially tolerated these marriages for their usefulness but soon sought (white) “Christian” wives whose reproductive and domestic labors could help them build permanent settlements of their own.14

By the time of Juana’s capture, devastating changes over which Indigenous people had no control threatened their survival. From the moment Spanish forces first landed in Mexico in 1519 and declared war on the Native inhabitants, they and their livestock transmitted pathogens that were more lethal than the bullets from their guns. In a pattern repeated across the Americas, epidemic diseases ravaged the Indigenous population of New Mexico. About 86,000 Pueblos farmed and hunted in the area in 1598, when Spanish leaders backed by a few hundred soldiers declared that New Mexico was a Spanish colony. In 1680, the Indigenous population in the area had plummeted to just 17,000. Demographic catastrophe affected sexual behaviors. Many of the hundreds of Indigenous nations in North America already permitted a man of high status to marry more than one wife; amid the challenges posed by colonialism, this practice expanded as a strategy to extend kinship bonds.15

Juana’s mother had come of age as Franciscans’ efforts to enforce Catholic sexual morality became especially violent. Franciscans arrived in New Mexico at the vanguard of Spanish conquest, eager to convert the inhabitants of Pueblo villages. They believed that God’s laws commanded chastity before marriage, fidelity within marriage, lifelong and indissoluble monogamy, and modesty. They even critiqued the sexual position that Pueblos apparently preferred, calling it “bestial”: “like animals, the female plac[ed] herself publicly on all fours.” Such a dishonorable means of copulation, the friars warned, lowered people to the level of animals. They advised that the only Christian position for sexual intercourse had the man and woman lie face to face, with the man on top—thus the “missionary position.” The friars preferred it because it favored what the Catholic Church officially considered the primary end of marital sexual intercourse, the conception of children.16

Franciscans believed they could educate Pueblos to avoid the wages of sin. Men and women who violated Christian laws might be put in the stocks and publicly whipped. Priests cut off disobedient men’s hair, leaving them with what the Pueblo considered shamefully short locks. Franciscans’ own behavior undermined their efforts to set a virtuous example. Taos Pueblos complained to the Spanish governor in 1637 and 1638 that the friar there had punished insolent children by castration and acts of sodomy. That friar was eventually relieved of his duties, but resentment built against the friar who replaced him, frustration that culminated in an attack in 1639 that killed the friar and two soldier-settlers.17

Seven-year-old Juana, meanwhile, traveled with her captors to a Diné village. She could already speak both Keres (the Zía language) and Spanish; now she learned the Diné language. Linguistic fluency was a valuable commodity in a region rife with intercultural alliances and conflicts. Juana entered the Diné community as a captive, but at some point she was likely adopted into a Diné family or married to a Diné man. She would leave their custody as something closer to kin.18

While Juana walked or rode into Diné territory in 1680, her Pueblo kin were secretly organizing a massive rebellion against the Spanish-Catholic presence. Fury over Franciscan attempts to suppress polygamy and other Pueblo sexual practices fueled the rebels’ determination. They also observed the weakness of the colonizer’s power. Spanish reinforcements arrived only once every three years from Mexico City, the nearest colonial center. Spanish power in the region was never firmly established, and it declined year after year. What became known as the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 left 400 Hispanics dead, including 21 priests. Soldiers from multiple Pueblo communities seized control of New Mexico and drove out 1,500 Spanish soldiers, friars, mestizos (people with a mix of Spanish, Indigenous, and often also African ancestry), and Indigenous servants. Those exiles retreated to El Paso, a community that came into existence as a refugee settlement. Perhaps Juana’s Spanish father and half-brother were among that beleaguered party.19

Juana “la Coyota” Hurtado lived twelve years among the Diné. The captivity that she experienced typified a form of slavery that had existed across North America and around the globe since ancient times. As early as 700 CE, captive labor enriched the powerful and possibly tyrannical leaders of the pueblos of the Southwest and within the vast agricultural power centers that emerged along the Mississippi River and its tributaries. Warring tribes seized people from their enemies’ villages to trade among themselves. At annual trade fairs, captives could be “ransomed” while bison meat was traded for vegetables such as squash, beans, and corn. That hierarchical Indigenous power structure had crumbled by the time Juana’s Pueblo grandmother was born, brought down by prolonged droughts and famine that undermined the authority of oppressive chiefs. Captivity did not end when those cultures collapsed, but it did morph into something less severe. (Servant captives, for instance, were no longer ritually killed and buried alongside a recently deceased master.) Indigenous slavery in the seventeenth century was nonetheless violent and disruptive. In warfare and diplomacy, tribes traded women and children. Only someone who was a foreigner, an outsider, could be a captive.20

In 1692, Juana’s Spanish half-brother Martín Hurtado “ransomed” her during Spain’s bloody reconquest of New Mexico. Spanish forces in El Paso had spent years plotting, and they recaptured all major Pueblo villages by 1693. Now a young woman, Juana requested and received a land grant near Zía Pueblo. There she established a prosperous rancho where Diné, Pueblo, and Spanish people traded for a half century. Juana eventually possessed three houses on two ranches, husbanded hundreds of livestock, kept more than thirty horses, and filled her homes with material possessions.21

She shared much of her post-captivity life with a man named Galván from Zía Pueblo. They had four children together by 1727, all of whom the Franciscans considered illegitimate because Galván was married to another woman. Juana disagreed. She went by the name Juana Hurtado Galván, adding her lover’s last name to her own. In doing so she honored a Pueblo (and more broadly American Indian) emphasis on kinship rather than wedlock as the foundation for intergenerational and community bonds.

Juana Hurtado Galván operated her businesses and conducted her personal life according to her own fusion of Zía Pueblo and Catholic values. She acted as an interpreter between the Diné people who frequented her ranches and the Franciscan priests who wanted to evangelize them. “They [the Diné] had kept her for so long,” Fray Miguel de Menchero wrote, “[that] the Indians of the said Nation made friendly visits to her, and in this way the father of the said mission has been able to instruct some of them.” She was esteemed among Pueblo, Diné, and Spanish alike, “favored by certain people,” one of her contemporaries noted, so that she could defy laws that attempted to punish her sexual behaviors. Spanish ideals of honor and chastity dictated social ostracism for such a woman as Juana, but she died secure in her wealth, power, and family bonds in 1753, at the age of eighty.22

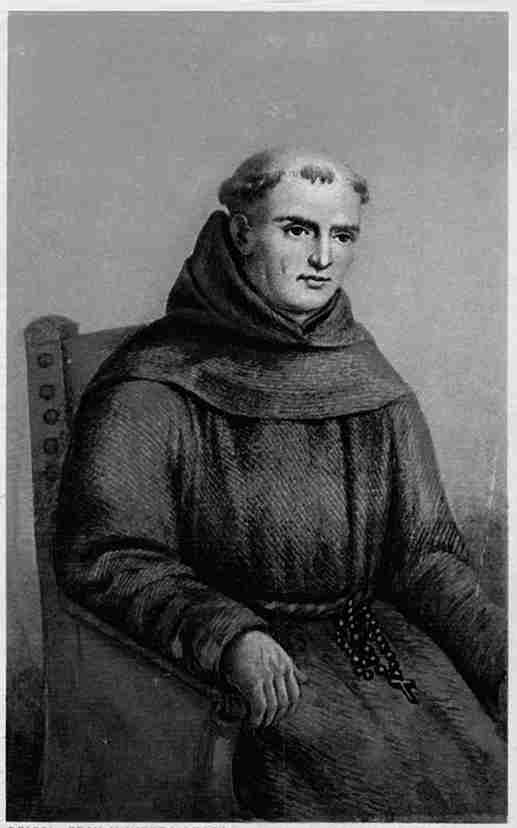

Juana’s notable refusal to conform to Catholic sexual morality could not, of course, dampen the zeal of the Franciscans determined to convert what they considered the heathen people of North America. By the mid-eighteenth century, with Spanish outposts in New Mexico more secure, colonial authorities in Mexico turned to establishing settlements along the coast of “Alta California,” a vast Mexican province that stretched north from the Baja Peninsula along the Pacific coastline. Founding Catholic missions in Alta California was the great passion of Fr. Junípero Serra, a Franciscan priest who created Mission San Diego, the first in Alta California, in 1769. By 1773, Franciscan priests had established five missions, but they were small and largely unsuccessful.

Spanish priests and administrators in California confronted sexual dilemmas similar to those facing English and French colonists: how to build a permanent settlement while prohibiting their men from cohabiting with local women. Serra recognized that celibate priests could not model the Christian marital sexuality that he wanted Native people to emulate. In 1773, he petitioned the Spanish government in Mexico to send him Spanish families so “that the Indians, who until now have been very surprised to see all the men without any women, see that there are also marriages among Christians.” Fourteen Spanish families settled San José in 1777, but fewer than 500 Hispanics lived in San José by 1810.23

Franciscan priests established Catholic missions in Mexico and California throughout the mid- to late-eighteenth century with varying levels of success. Father Junípero Serra (1713–1784), who founded Mission San Diego in 1769, hoped not only to convert Indigenous people to Catholicism but to eliminate what he viewed as depraved sexual practices between Native men and women.

A new Hispanic identity emerged among residents of this region who claimed Spanish ancestry, a heritage that they believed entitled them to lands that Spanish colonists had seized from Indigenous people. Most of the first Hispanic settlers of California were not, in fact, “pure” Spanish but mestizo. Those family histories shaped an emerging Hispanic sexual subculture. Among Hispanic men and women who lived throughout New Spain in the mid- to late eighteenth century, honor depended not as much on private behavior as on public reputation. Like their Anglo-American contemporaries, they tolerated premarital sex as long as it resulted in marriage.24

Fr. Luis Jayme, a priest at Mission San Diego, shared Serra’s understanding of sexual behavior as both a tool of conversion and a measure of the convert’s obedience. Jayme believed he could transform heathen polygamists into married Christian monogamists. He boasted that Native converts displayed their new faith by abandoning their tribes’ sexual norms: “They do not marry relatives [once they convert],” he explained, “and they have but one wife. The married men sleep with their wives only.” The “bachelors” at the mission slept in a separate dormitory rather than in the family groupings that Native people more often preferred. Jayme proudly disciplined Indigenous people who failed to comply with Christian sexual morals: “If a man plays with any woman who is not his wife, he is scolded and punished by his captains.” Punishments included public whippings.25

Spanish soldiers, who built presidios, or forts, near the missions, threatened the priests’ aims. Already by 1772, the residents of Indigenous towns near Mission San Diego prepared to attack the mission because, Jayme explained, Spanish soldiers terrorized locals, who fled their homes each morning “so that the soldiers will not rape their women.” This violence was not a distinctive horror of Spanish rule. In 1752, leaders of the Lower Creek nation complained to an agent of the South Carolina government that “the white people in general [were] debauching their wives and mentioned several in particular that were found guilty, and said if his Excellency would not punish them for it, the injured persons would certainly put their own laws in execution.” Women healed themselves using purification rituals, but the abuses continued.26

Fury over these sexual assaults fueled a wave of violent rebellions. In 1771, soon after Mission San Gabriel was established in California, a large group of Indigenous people avenged the rape of a woman from their tribe by ambushing two Spanish soldiers on horseback. The Spanish counterattacked, bringing the head of the local chief back to their presidio. Indigenous nations that had previously been enemies formed a council to mount a unified front against the Spanish. Only the arrival of Spanish reinforcements at the mission foiled their plans. A Spanish soldier’s rape of a woman married to another chief similarly instigated an insurrection at San Luis Obispo. Spanish soldiers intercepted the attack, but not before Native people demonstrated their outrage at Spanish behavior.27

Time and again, Native people refused to abandon their longstanding sexual practices even as they accommodated some of the friars’ religious requirements. Many compromised, complying with Catholic marriage within the mission’s walls while holding to their Indigenous sexual values beyond them. Serra complained to the governor of California that the Indigenous men he oversaw “have, each, a gentile woman with them, and have left their Christian wives here at the mission.” Priests grilled converted Indians about their sexual desires and behaviors at annual confessions and during prenuptial investigations, inquiring whether they had “carnal” dreams about men, women, or animals; whether they became aroused at the sight of animals having sex; whether a man had raped or had sex with a joya (a two-spirit person); and whether they had ever tried to prevent a pregnancy, among other questions. The answers they recorded reveal not the scrupulous avoidance of sin but the lengths to which many Indigenous Catholics went to embrace both Catholic and Indigenous teachings about sex.28

Antonio Pablo was a neófito, an American Indian who had converted to Catholicism and who resided just outside the walls of the mission at San Juan Capistrano in California in the early 1800s. A widower, he decided after his wife’s death that he wanted to share his bed with a woman named Felicitas. While the priests who kept records at the mission did not make note of Pablo’s tribal identity, the Native people of California included dozens of distinct language groups and polities.29

The Franciscan friars at San Juan Capistrano, though, berated Pablo for living “obscenely” with Felicitas and committing adultery: Felicitas was married to another man. Religious education in Mission San Juan Capistrano had instructed Antonio Pablo in the Catholic Church’s teaching against fornication and adultery, but much as Juana Hurtado had in early eighteenth-century New Mexico, he rejected the notion that he had committed a religious offense.30

Europeans brought disease and warfare, but their arrival did not extinguish Indigenous people or their cultures. Juana’s story reveals how individuals who experienced captivity and possible sexual assault might continue to choose which sexual norms they wanted to follow, despite considerable pressure to adopt a colonizer’s moral code.