Chapter 3

Under the Husband’s Government

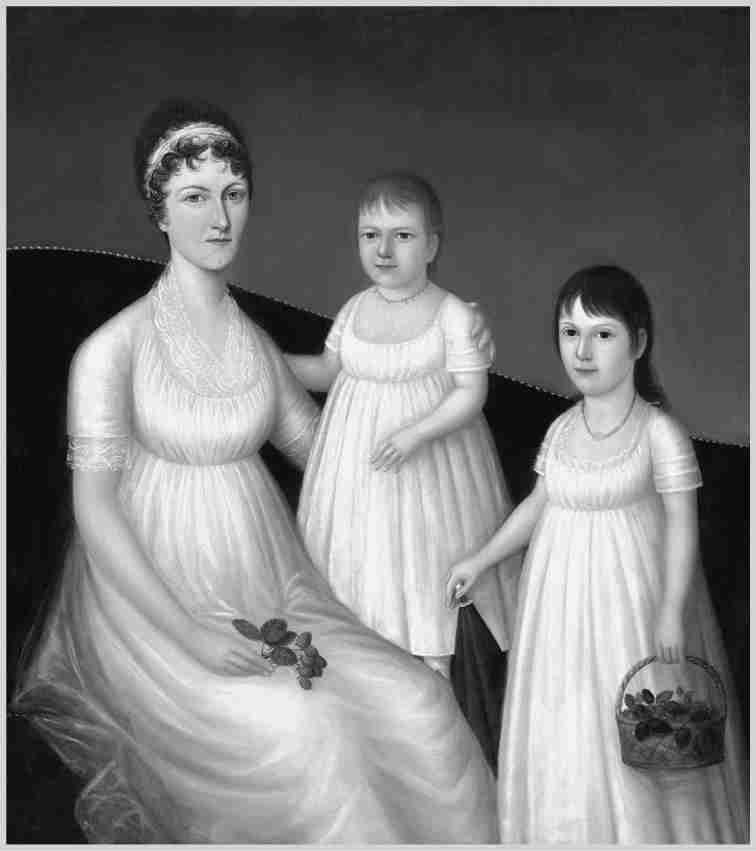

To an eighteenth-century viewer, the many offspring of this husband and wife represented the ideal outcome of marriage. Historians believe that the younger, seated woman holding an infant is the adult child of the older woman, also seated with an infant, suggesting that mother and daughter had both recently given birth. The toddler-sized child, painted in a somewhat translucent hue, might represent a child who died very young.

When Abigail Abbot Bailey realized her husband, Asa, had deceived her, carrying her into New York State in 1792 and then abandoning her there, she called upon God to guide her back to her children, relatives, and religious congregation in New Hampshire. For years she had waited for God’s will to reveal itself, until she finally pursued an informal separation from Asa. She hoped “to suffer him to flee . . . and . . . go to some distant place, where we should be afflicted with him no more,” if only he would fairly divide their property between them and then leave her alone. Asa initially refused to do that, even after Abigail confronted him with evidence of his sexual abuse of their teenage daughter Phebe. Like many women of her era, Abigail hesitated to seek a divorce, “the dreadful scene of prosecuting my husband.” The laws of New England permitted divorce on limited grounds, including adultery and cruelty, but her Protestant faith in the marriage covenant had led her to seek an alternative.1

Abigail’s experience of marriage in the eighteenth-century United States was a terrifying one, but it needn’t have been. When Abigail Abbot reached the age of twenty-two in the 1760s, she could have reasonably expected that marriage would bring her joy and fulfillment. Her religion taught her to put her trust in God, and it also promised her companionship with her husband. Law defined a wife as her husband’s inferior, but Abigail also hoped that love might blossom in her home and pleasure reach her bed. Poetry and essays in popular Anglo-American magazines in the mid-eighteenth century celebrated romance; by century’s end, letters exchanged by courting couples—and rationales given in court for a divorce—often referenced the presence or absence of affection and the suffering of the brokenhearted. Husbands were the family patriarchs, but patriarchs were expected to be kind. As Boston preacher and Harvard College president Benjamin Wadsworth explained in 1712, within the family hierarchy, “the Husband is call’d the Head of the Woman,” and governs the wife accordingly. Yet a husband should not treat his wife “as a Servant, but as his own flesh; he must love her as himself.”2

Neither the religious ideals nor the legal options of the time accounted for a husband like Asa. His violent domination subverted the terms of his marriage covenant and endangered the lives of his dependents. Abigail prayed for Asa’s redemption and wrote in her journal about her desire to understand how God’s plan for her included the endurance of domestic terror.

Ideals of marriage, love, and sexual pleasure had deep roots among New England Protestants. Contrary to modern assumptions of their prudery, seventeenth-century Puritans described marriage as an ideal friendship, and they emphasized that both husband and wife should find erotic satisfaction within it. “If ever two were one, then surely we,” the seventeenth-century Puritan poet Anne Bradstreet wrote to her husband. A popular understanding that women were, if anything, more driven by sexual desire than men prompted the authors of domestic advice manuals to emphasize that conjugal love should be not only romantic but mutually satisfying. One midwifery text urged husbands to “entertain” their wives “with all kind of dalliance, wanton behavior, and allurements to venery” to ensure her “content and satisfaction.” New England courts upheld divorce petitions from wives whose husbands were impotent, ruling that a man who could not sexually perform for his wife had failed to meet one of the most basic requirements of marriage.3

This Protestant celebration of conjugal desire contrasted to the increasingly vociferous disparagement of sodomy. Few sodomy cases made it to court, but ministers preached against it regularly. By the 1730s, American newspapers carried articles about gathering spots in London for men seeking sex with one another called Molly houses, with similar enterprises known by other names in the Dutch Republic, Lisbon, and Paris. Coverage of these “sodomitical clubs” hinted at a nascent concept of sexual identity among these “vile Wretches” and the sexually defined communities they formed, but we have no record of any comparable groups taking shape in Anglo America.4

The idea that sexual behavior reflected the state of a person’s soul, rather than an internal sexual identity, nevertheless allowed for leniency toward men who had sex with men. In 1756, when the General Meeting of Baptist Churches suspended Stephen Gorton, a minister of a church in New London, Connecticut, for “unchaste behaviour with his fellow men when in bed with them,” Gorton’s contemporaries bemoaned that his tendency toward sin manifested in forbidden sexual behaviors. The General Meeting determined that Gorton’s “offensive” conduct, “frequently repeated for a long space of time,” was evidence of “an inward disposition . . . towards the actual commission of a sin of so black and dark a dye.” Yet because Gorton’s contemporaries believed that his behavior reflected his chronic disposition rather than his desires, they also had faith that repentance could absolve him. He confessed his sins before his church, and the members voted by a two-thirds majority to reinstate him.5

The key for prosperous white men was to maintain a reputation for self-mastery. William Byrd II, an eighteenth-century Virginia enslaver and politician, kept a diary in which he recorded his sexual interests and acts. Byrd viewed his sex life as an expression of his privileged social status. He used a combination of genteel and military language to describe his marital and nonmarital encounters, such as when he wrote in the 1710s that he “gave [his] wife a flourish” or characterized intercourse as “mount the guard.” He noted the various times he “rogered” his wife, including her displeasure when he did this while she was ill, and recorded his assaults against various other women. (“Roger” was slang for penis.) He referred to sex workers as “ladies of universal gallantry”—surely a joke, but one that allowed him to see his patronage of sex workers as further evidence of his civility.6

The Protestant revivals that swept from the Carolinas to New England during Abigail’s childhood called believers to a purer ideal of sexual virtue. From the pulpits of Congregationalist churches to the tent revivals of Methodist itinerants, mid-eighteenth-century Protestants emphasized the emotional vulnerability and passion of the converted sinner’s experience. Women and men wept at Baptist and Methodist gatherings as they confronted their sins and begged for God’s forgiveness. Churches required confession and penitence for sinners, but these practices showed differing understandings of men’s and women’s weaknesses. Women, far more often than men, were disciplined for sexual misconduct, while secular and church law punished men more often for the sins of avarice and inebriation. Indeed, popular wisdom assigned men a greater capacity for self-government, an ability to regulate their “passions” that women, left to their own devices, generally lacked.7

When Asa courted Abigail in the 1760s, he may have visited her father’s home to bring her gifts, stay for conversation, and possibly take the first steps toward sexual intimacy. By the mid-eighteenth century, rather than family patriarchs arranging marital partners for their children, young men and women chose for themselves. Asa would have asked Abigail’s father for his approval, but Mr. Abbot most likely did not select Abigail’s husband.8

Their courtship coincided with the heyday in New England of a practice called “bundling,” imported from northern Europe, in which parents permitted their daughter’s suitor to spend the night in her bed. Bed-sharing remained as common in the mid-1700s as it had been in the 1620s when T. Hall lay beside Greate Besse. Travelers often crawled into bed with one of their hosts, even a young woman of the house. But bundling was different. An English visitor to Massachusetts 1759–1760 observed that after the “old couple” of the house went to bed, “the young ones . . . get into bed together also, but without pulling off their undergarments, in order to prevent scandal.” It was common in the small New Hampshire towns where the Abbot and Bailey families lived too. A young farmer in Keane named Abner Sanger wrote in his journal that he and other young men he knew enjoyed what they called “girling of it,” casual overnights in the beds of young women their age. Bundling seems to have been especially common among rural and non-elite people. Clergy warned against it. In 1753, minister Samuel Hopkins condemned behaviors that “have a tendency and lead to the gratification of lusts,” including “unseasonable company-keeping” and “lying on the bed of any man with young women.” Hopkins seems to have held a minority opinion. For most New Englanders, bundling was neither outrageous nor clandestine, and a household’s senior residents allowed it for couples who were not even engaged.9

Bundling’s popularity grew as the American legal system’s concern with sex crimes declined. Throughout the seventeenth and into the mid-eighteenth centuries, New England authorities vigorously prosecuted fornication and heard white women’s allegations of forced sex. But after about 1750, courts in British North America rarely took on cases involving sexual assault, bastardy, or fornication. Commercial disputes filled their dockets instead. Families and communities assumed responsibility for sexual matters and negotiated informal resolutions. Those changes deprived many women of the ability to have their voices heard in court. Now when accusations of illegitimacy or forcible sex came before the bar, they did so more often as lawsuits for reputational damage brought by one man against another.10

The acceptance of bundling suggests not only that playful premarital intimacy filled the lives of many young people of the time but that it gave young women—and their families—significant leverage at a time when they could no longer reliably litigate fornication, illegitimacy, or sexual assault. A young woman likely had some control over whether she and her bedmate remained fully or partially clothed. In the small homes of the time, other members of the household would have easily heard if she called out for help. And a parent whose daughter “bundled” with a suitor would have known whom to hold responsible (and pressure into marriage) if she became pregnant.11

Bundling may have contributed to high rates of premarital sex: by the 1770s, between 30 and 40 percent of the brides in New Haven were already pregnant when they spoke their marriage vows. Abigail was not pregnant on her wedding day. Given the intensity of her faith, she likely would have strongly preferred to save her first sexual experiences for her marriage bed. She might also have wanted to make sure that Asa followed through on his promises.12

Marriage was hardly a bedrock of “tradition” or Christian morality among white Americans. In the South, where ministers were in much shorter supply than in New England, marriage was a frequently informal arrangement. In 1711, Reverend John Urmstone, an Anglican, bemoaned the “troublesome and unsettled country” of colonial North Carolina, a “barbarous and disorderly place.” Nothing captured that disorder, he complained, more than the sexual indiscretions of married women. More than fifty years after Urmstone’s tirade, in 1766, Anglican minister Charles Woodmason complained that the white inhabitants of the South Carolina backcountry lived in a “stage of debauchery,” with polygamy “very common,” “concubinage general,” and “bastardy no disrepute.”13

Americans extolled marriage as a partnership of loving companionship, but they still privileged the power of household patriarchs and the needs of the larger community. Marriage in the United States adhered to the common-law principle of coverture, according to which the husband’s legal identity “covered” the wife’s. Under coverture, a married woman—a feme covert—could not establish a separate residence or enter into any contracts without her husband’s permission.

Despite those restrictions, the laws of marriage in New England were more liberal than those in Britain or even in the mid-Atlantic and southern regions. In most colonies and states, it was easier to obtain a legal separation (usually separation “of bed and board,” with no legal right to remarry) than a civil divorce, but divorces became more common after the Revolution. The most frequent means of separation remained “self-divorce,” when husband and wife simply parted ways without legal formalities. (Self-divorce on occasion led desperate husbands to pay for newspaper notices warning others not to enter into contracts with their estranged wives, whose debts, under coverture, they would be legally obligated to honor.) Throughout the new United States, women made up most plaintiffs in divorce cases.14

Abigail’s hopes for marriage reflected the era’s celebration of romantic love as well as her religious worldview: through prayer and subordination to Asa within the marriage covenant, she would serve God. Protestant theology granted spiritual equality to men and women, but a wife could exercise authority only indirectly. A woman married to a deeply disturbed, violent man, who was otherwise a pillar of his community, had to tread carefully.15

Depicted by a French historian, this portrayal of childbirth in early America illustrates both its intensity and normalcy. Dressed in everyday clothing and sitting on household chairs, a small group of men and women brace the mother and help deliver the child. Indeed, these scenes were not uncommon in eighteenth- and early-nineteenth century America; in 1800, the average white woman experienced seven live births in her lifetime.

Initially, at least, Asa Bailey’s sexual energies burnished his reputation for being a capable patriarch. Abigail married Asa in 1767 when she was twenty-two and gave birth to their first child ten months later. For the twenty-five years that Abigail lived with Asa, helping him manage a farm in Bath, New Hampshire, she had sixteen pregnancies, including two sets of twins. Only one of these pregnancies ended in a miscarriage, and two of Abigail’s children died in infancy. The babies usually arrived at eighteen-month intervals, but her son Samuel was barely two months old when Asa came to her bed and they conceived a daughter, Phebe, who was born in April 1772.16

Abigail’s prolific fertility was exceptional and fast-paced even for the New England colonies, which had an astonishingly high birth rate compared both to England and to the English colonies of the Chesapeake. A white woman in British North America typically bore children every two years until she entered menopause, averaging perhaps five to ten pregnancies, with three to eight surviving children. Birth rates for enslaved women varied; they were lower on a large South Carolina plantation than at Thomas Jefferson’s labor camp at Monticello, likely the result of harsher living conditions in the Carolinas. Between this reproductive success and ongoing immigration (including the forced migration of enslaved people from Africa), the population of the British colonies in North America exploded from 251,000 in 1700 to 2,464,000 in 1773.17

Abigail was fortunate to have survived those many times she was “brought to bed,” as women of her generation were in constant danger of death in childbirth. As it was, all of those pregnancies, childbirths, and lactations took a toll on her health. She was often exhausted and felt physically weak. Yet she seemed to understand that bearing children reflected God’s plan for her life. No evidence suggests that Asa and Abigail attempted to have fewer children.

Women of Abigail’s generation who wanted to limit the frequency of their pregnancies employed a variety of methods. Withdrawal prior to ejaculation was a common form of fertility limitation, although contemporaries may have overestimated its efficacy. A white man in colonial Massachusetts defended himself against charges of illegitimacy by telling the court he could not be the child’s father because he “minded [his] pullbacks.” Folk-medicine traditions taught lactating women that breastfeeding might suppress their fertility, and they also discouraged sexual intercourse with a lactating woman; many women extended the number of months they kept a baby at the breast to space their pregnancies further apart. Other women also used pessaries, a substance or device placed in the vagina to block or neutralize sperm, varieties of which had existed since ancient times.18

Women made decisions about whether to prevent or end a pregnancy based on a widely shared understanding that the fetus’s life began with “quickening,” the moment at which a pregnant person perceived fetal movement. To restore “blocked menses,” women consumed herbs like pennyroyal, sage, snakeweed, calamint, and tansy; brewed teas; laid on poultices; and tried other popular remedies. “Blocked menses” was an ambiguous phrase that connoted the cessation of menstruation due either to ill health or to pregnancy. In 1760, a druggist named Nathaniel Tweedy advertised that his store carried “small ivory syringes,” as well as Hooper’s Female Pills and Fraunce’s Female Elixir, both known as remedies for menstrual irregularity. Syringes might be used for douches, to dilate the cervix, or to intrude into the uterus to induce abortion.19

However often early Americans discreetly intervened to prevent or end a pregnancy, they publicly celebrated their fecundity. They showered respect and admiration on the fathers of large families. Women’s fertile bodies symbolized abundance; almanacs and newspapers used adjectives like “teeming,” “lusty,” and “breeding” to describe the expanding bodies of pregnant women. Wealthy American women paid portraitists to depict them seated with fruits in their laps, like wombs ripening with new life. Abigail’s descriptions of her fatigue and ill health attest to the physical burdens of frequent pregnancy and childbirth, but her fertility would have burnished Asa’s reputation.20

The window in Abigail Bailey’s bedroom framed a bucolic scene. For as far as her eye could see, cultivated fields and flocks of sheep and cattle adorned the fertile valley west of the White Mountains. She spent many weeks of her adult life in that room, resting during difficult pregnancies, laboring during childbirth, and nursing the infants who arrived in steady succession. She prayed there, too, begging God’s forgiveness for what her husband was doing with the young women living under their roof.21

Abigail had been Asa’s wife for only three years when he had a sexual relationship with a live-in domestic servant. Abigail believed the relationship was consensual, although she did not consider (as no one at the time would have) that an employer’s power over a servant’s livelihood limited the very concept of consent. To Abigail, what mattered was that this young woman was “rude, and full of vanity” and that “her ways . . . were pleasing to Mr. B.” A man of high status like Asa Bailey could get away with a lot. Like many white men of his era, Asa presumed that Black, enslaved, and white working-class women would agree to sex and that force was an appropriate response if they refused.22

In the mid-1770s, another woman hired to perform domestic chores for the Bailey household alleged that Asa “made violent attempts on her.” (English common law defined rape as “unlawful carnal knowledge of a female over ten years of age by a man not her husband through force or against her will.” After American Independence, states adopted versions of that definition.) Asa had approached this servant with his standard opening gambit. First, he flattered her, trying to get her to laugh. When she refused what Abigail described as his “unseemly” conduct, he used force. She fought back and got away from him. Abigail had more sympathy for this woman than for the woman who had sex with her husband earlier in her marriage. She confronted Asa after she heard about the attempted assault, maintaining a calm demeanor that, she believed, was evidence of the depth of her faith (and also, likely, a practical attempt to avoid a reprisal).

Still, Asa became so enraged that Abigail feared for her life. “He fell into a passion with me,” Abigail wrote. “He was so overcome with anger” that he collapsed and spent the rest of the day in bed. Asa could not tolerate Abigail’s refusal to express anger or agitation. “I never saw such a woman as you,” he spat. He transformed her stalwart commitment to “peace” into a justification for his own rage.

Evening fell as Asa remained prostrate, nursing his supposed wounds. The cows needed milking, and Abigail knew that tending to them would leave her vulnerable—out of doors, alone, bent over, and ill prepared to run. She was five months pregnant and had four small children, none older than five, waiting for her back in the house. It seemed only too possible that her “poor husband . . . might not be suffered to add to his other crimes that of murder.” She went to the barn anyway; God, she believed, would protect her. For good measure, she whispered a prayer for her husband while she filled her pails and returned to the house.

Abigail had been right to think that Asa might kill her. He admitted as much. Calmer now, he told her that he had “thought that he would put an end to [her] life” but had decided not to. Cultivating Abigail’s pity, he declared a newfound interest in discovering Christ’s love. Asa had never been as devout as Abigail was (she had converted when she was eighteen, but Asa was unconverted), and although in the past she greeted his pledges to dedicate himself to Christian morals with optimism, she at last doubted his sincerity. Even so, she hoped that he might yet convert. Any means of household comity was welcome.

The young woman they had employed was not satisfied with Asa’s professions of faith and went to a grand jury in 1774, attesting that Asa tried to coerce her to have sex with him. “All but the violence used, Mr. B. acknowledged,” Abigail noted. The Baileys would now be the subject of neighborhood gossip about their unruly household. It was yet another burden that Abigail would have to bear. Yet within just a few years, Asa was given a major’s commission at the head of an army regiment. “He was indeed a man of abilities,” Abigail conceded. The family’s reputation, for now, was intact.

Malicious gossip, far more than prosecution for sex crimes, threatened abusive white men. Sexual reputation affected their ability to amass wealth. Because the era’s financial networks relied on personal ties as much as business interests, it was other men’s opinions that mattered to a merchant’s ability to get credit. In taverns, coffeehouses, and print culture, men mocked other men who had failed at business as harpies or described them as feminine victims of rape, “ruined,” much as a seduced woman was, by a scoundrel. As long as a man’s sexual adventures enhanced rather than diminished his reputation for virile patriarchy, he could still brag of his conquests without fearing a loss of social standing.23

The legal system gave wide latitude to white, landowning men accused of rape such as Asa but meted out harsh punishments for similarly accused men of African descent. Black men accounted for the overwhelming majority (80 percent) of men executed for rape in British North America and the United States between 1700 and 1820. White men accused of rape were far more often charged with lesser forms of sexual assault. Several colonies specified brutal punishments for Black men; Delaware sentenced an enslaved man convicted of rape to four hours with his ears nailed to the pillory and then “cut off [his ears] close to his Head.” White men who exploited free or enslaved Black women faced no legal punishment. The sexual abuse endemic to the transatlantic slave trade was so pronounced, and its effects so enduring, that it was part of the very fabric of American life.24

Ideas about white women’s virtue emerged in tandem with stereotypes about Black men. During the American Revolutionary period, Americans started to think about white women as uniquely sexually fragile. This ideal applied far more to middle-class women like Abigail than to the servants who worked in her home. It marked a dramatic change. In Philadelphia, a city known for having an especially relaxed attitude toward nonmarital sex, popular ditties and poems in almanacs of the 1750s through 1770s teased about lusty maidens and sexually frustrated widows, portraying men, by contrast, as torn between their erotic impulses and their pursuit of mastery over their desires. Revolutionary politics abetted a notable shift: patriotic literature urged white women to recognize that they served their country by modeling virtue for their husbands and sons, as the wives and mothers of the new republic’s male citizens. Presumptions that women were submissive, chaste, and even “passionless” supplanted earlier stereotypes of lusty temptresses descended from Eve. These ideas rendered middle-class and elite white women nearly immune from suspicions of sexual immorality.25

Stereotypes about lusty maidens were instead transferred onto working-class and non-white women. An anonymous diarist in the 1790s cataloged his sexual engagements, claiming he had “topped” thirty-six “wenches” the year before, maintained two mistresses, and paid five women for sex. The word “wench” was a derogatory term that conflated a woman’s poverty with her sexual availability. This diarist created pretexts for his wife to leave the house so that he could harass a household employee, Nancy Jones, with demands for sex. When she complained to his wife, he fired her. By the late eighteenth century, white people used “wench” to describe Black women of all classes.26

Asa and Abigail Bailey’s eldest child, a daughter named Abigail, was only six years old when, in 1774, a jury acquitted her father of attempting to forcibly rape their household servant. As she and her siblings grew to adolescence, they learned to fear their father’s “severe chastisement upon his children.” Ruth, the second eldest child, married a man named Ebenezer Bacon when she was sixteen, leaving her father’s home to tend to her husband’s household at a significantly younger age than most women of her generation. We might ask what motivated her. Another daughter, Phebe, was thirteen when Ruth married and moved out. Abigail Bailey later described the “hard and cruel treatment” she experienced as Asa’s wife, but it paled in comparison to what Asa inflicted on Phebe.27

Asa Bailey was financially secure by the 1780s, with hundreds of acres of farmland in his name. For more than two decades, he violated his marriage vows and committed numerous acts of sexual violence before he faced any threats to his reputation, let alone to his freedoms. In this, he was not unusual for a white, landowning man in early America.

But Asa had grown increasingly erratic. He speculated about moving the family westward. Abigail had recurrent dreams that he sold the farm and took three of their children with him. In one dream, he murdered the children. For years, Abigail had practiced “prudent management with him” to navigate his “unhappy temper,” but Asa’s standing in their community was faltering. The respected citizen who had been awarded a major’s commission in the mid-1770s was by the early 1780s embroiled in land disputes, part of a “rabble” that tried to knock a local official off his horse when he delivered unwelcome news about their land titles.28

To Phebe’s horror, her father’s eye turned toward her. Much as he had with the young women they employed, Asa first tried to obtain Phebe’s agreement to sex. “A great part of the time he now spent in the room where [Phebe] was spinning,” Abigail recalled, “and [he] seemed shy of me and of the rest of the family.” Asa joked with Phebe, told her stories, and sought her attentions. When he informed Abigail that he wished to take Phebe with him to Ohio to care for him, she grew alarmed.

Abigail described the abuse as a corruption of her marriage. “My room was deserted,” she explained, as Asa lavished attention on their daughter instead. Asa continued to expect sex from his wife, as she may have expected it from him as well; their twins Judith and Simon were conceived the same month that the abuse began.

Phebe was terrified of her father and kept younger siblings around her to avoid his predations. But she could not stop him. Asa raped Phebe when Abigail traveled to see friends or family or was otherwise out of the house. When Phebe resisted her father’s “vile conduct,” he beat her with a beech stick “large enough for the driving of a team.”

The assaults continued for over a year, from December 1788 to April 1790. Phebe’s younger siblings witnessed much of it, eventually telling all to an older sister who lived elsewhere. In her memoirs, Abigail relayed the grim story in her own terms. She defended her decision not to leave Asa as soon as she learned of the incest by explaining that she was sick at the time she discovered it; she was pregnant with the twins, born in September 1789, one of whom lived only seventeen days. As she recovered, Asa “proceeded in his wickedness.”29

When Phebe turned eighteen and was no longer her father’s legal dependent, “she immediately left us, and returned no more.” Within a few months of Phebe’s departure, Abigail was once again pregnant. (Legally, Abigail herself had no basis for refusing sex with an abusive husband. His marriage rights included the right to sex with his wife.) Another daughter, Patience, was born on May 27 or 29, 1791.

Abigail began to seek an informal agreement with Asa that he would leave their home, allow her to raise the children, and give her half the value of their property. Abigail also knew that if she left home without some kind of settlement from Asa, she would be penniless and might lose any legal entitlement to her children.

Rumors seemingly carried by “birds of the air” spread word of the incest and of Abigail’s demand for an informal separation. Abigail warned her children “that they must no longer expect to derive the least advantage from being known as the children of Major Bailey.” In political print culture and coffeehouse conversations of the Revolutionary era, rape symbolized the excesses of a louche aristocracy, while virtuous citizens of a republic displayed self-control. A piece in the Boston Journal in 1780 reminded patriotic men that British soldiers had harmed the property of patriots, “their farms laid desolate;—their property plundered;—their virgins ravished.” Abigail likely worried about her family’s reputation, including how it would shape Phebe’s marriage prospects. But that reputation was already shattered.30

Proving adultery—the legal fault that would permit divorce—required Phebe’s testimony, something that the shy and possibly terrified girl was unwilling to give. Abigail shared Phebe’s fear of shame and exposure, which would be “inexpressibly painful.” They had reason to avoid provoking a man who had threatened to kill them. Yet Abigail also resented Phebe’s recalcitrance.

This seeming lack of sympathy for Phebe is difficult to comprehend. Perhaps Abigail was too exhausted from frequent pregnancies to defend her daughter from Asa’s attacks. Her reticence may also reflect her understanding that, under coverture, Asa possessed all of the parental rights. As a feme covert, Abigail could not establish a separate residence without his permission. She could not even claim her children as her own in a custody dispute.

Abigail may also have believed that she was successfully fulfilling her maternal obligations. She had reached adulthood understanding that it was her role to be a faithful wife and a fruitful mother; she loved her children by bringing them into the world and teaching them to love God. She might even have learned from her ministers’ sermons to interpret Phebe’s suffering as a test of her own religious practice of patience and submission. If Abigail did not outwardly express sympathy for her daughter until she learned the full extent of Asa’s abuse, she behaved in ways that her contemporaries would have found familiar; reports of child abuse and incest in divorce cases from the eighteenth century rarely expressed outrage on the children’s behalf. Even as ideas about natural rights and liberty reshaped American public life, how those rights extended to children remained unsettled. Ideas about motherhood as the center of family nurturing—of intensive, emotionally astute care for a smaller number of children—would emerge in the lifetimes of Abigail’s grandchildren, but not in hers.31

Amid Abigail’s attempts to negotiate a mutually agreeable separation, Asa took Abigail out of New Hampshire on the pretext that he had undergone a change of heart and would seek a buyer for their farm. The proceeds would allow an amicable division of their property—or so Abigail believed. No sooner had they crossed into New York State than Asa revealed his true intentions. He would keep the money from the sale on “terms, that would better suit himself” and abandon her, unless she agreed to be “a kind and obedient wife.” Likely predicting that Abigail might decide under these circumstances to seek a divorce after all, he waited to reveal these aims until they had entered a state with some of the strictest divorce laws in the country, where even an abused and neglected wife would have little recourse. Abigail faced this crisis hundreds of miles from her children, brothers, and church friends; informal networks of support often aided married women navigating a legal system that tilted toward the husband’s desires. (New York did not grant a single divorce between 1675 and 1787. That year, a new law allowed divorce only on grounds of adultery.)32

Smallpox had devastated several of the towns the couple passed through in New York, during weeks of what Abigail described as “captivity.” When Abigail and Asa arrived in Whitestown, where their eldest son, then about twenty-one, was living, Abigail was inoculated against the smallpox at the son’s urging, but she became ill from the disease nonetheless. Asa did little to attend to Abigail’s basic needs, instead forcing her to rely on the goodwill of strangers. In a small settlement where homes made from roughhewn timber lacked roofs and windows, the charity she received was barely enough to keep her alive. She survived as she had for so many years, praying and writing in her diary, and seeking any means she had to barter or labor for cash. Faith and fortitude had sustained her through years of Asa’s infidelity and violence—not to mention the births of seventeen children.33

After four months in Whitestown and other small settlements, Asa decided to walk back to their New Hampshire farm, still scheming about land deals and westward migration. He abandoned Abigail in a “hut” with no roof (although, inexplicably, he left without his horse). Abigail was certain that once he arrived at their farm he would take their young children—those who had not moved elsewhere—away from her forever. The law would certainly permit him to. But God, she believed, had other plans.

Abigail concluded that this was her chance to flee. She took out a piece of paper and recorded two sets of instructions for herself: directions to New Hampshire and the lyrics to hymns, including the words “Faith is our guide, and faith our light.” She closed her eyes and pictured the congregation in Haverhill, New Hampshire, where she worshiped among people “who kept holy day.”

She set out alone, on Asa’s horse, for the 270-mile journey home in late May of 1792, with less than a dollar in her possession. Her saddlebags contained clothes she might exchange for a night’s rest in a tavern, and she also resolved to sell her beads, shoe buckles, and stone sleeve buttons if necessary. She was desperate to see her children, the youngest of whom was just over a year old. She trusted in God to bring her back to them alive, not knowing if they had survived her absence. If in the past she had prayed for Asa’s redemption, she now recognized that she could not save him.

Abigail rode alone across rivers and up mountainsides, often finding shelter from charitable innkeepers who accepted silver clasps and articles of clothing in exchange for room and board. After months of additional travail, she reached the town where her youngest children had been staying. Even then, Asa had a co-conspirator attempt to kidnap them. With help from friends at her church and from her brothers, Abigail reunited with her children. They had suffered in her absence.

After the American Revolution, a new ideal of motherhood encouraged women to have a smaller number of children, whom they could educate and nurture intensively as future citizens of the young nation.

Only the very real possibility of standing trial for a capital crime (incest) persuaded Asa to sign a formal separation agreement, which gave Abigail a portion of the value of their farm and custody of all their minor children except one son, who went to live with Asa and two adult brothers. Those sons eventually left Asa and returned to their mother. Nearly another year passed before the divorce she petitioned for was final. Despite the divorce settlement, Abigail’s financial situation was precarious. She lived in a rented room and “put out” several of her children into apprenticeships. When Abigail died in 1815, she was living with her son Asa Jr. His father Asa Bailey lived to be eighty-two, an advanced age in that era, dying in 1826 in West Newbury.34

The sexual violence of the Bailey home seems to have influenced the choices of Abigail and Asa’s children. Their daughters at the very least made different decisions than their mother had about childbearing. Phebe and Patience never married, but seven of their sisters did. Abigail (b. 1768), Anna (b. 1777), Sarah (b. 1779), and Chloe (b. 1782) each had seven children, a dramatic reduction from their mother’s seventeen births. The sisters bore fewer children in part by marrying later; both Sarah and Chloe married when they were about twenty-eight years old. Olive (b. 1786) had her first and only child after she married in 1826 at the age of forty. Judith (b. 1789) had four children.35

In doing so, they followed many of their late-eighteenth-century contemporaries, a growing number of whom began to limit their fertility intentionally by combining familiar methods with new, more determined intent. Their efforts transformed pregnancy, childbirth, and nursing from the perpetual condition of adult female existence into a significant but briefer stage of adulthood. White American women in 1800 averaged seven live births; by 1850, it was five.36

Asa Bailey was a deeply troubled man, and the horrors of his household are not representative of the broader experience of marriage in the early national period. Sexual coercion—or the fear of it—was nevertheless a common experience for individuals living in all kinds of communities in the eighteenth century. Female indentured servants who married their masters, often because they were already pregnant, may not have entered those marriages happily. Individuals who experienced violence might protest against it, as the servant who brought charges against Asa did in the 1770s, but no organization or movement against domestic violence, rape, or corporal punishment advocated on behalf of victims. Violence was a specter that lurked as a possibility in everyone’s lives. As Abigail and her daughter Phebe learned, families and communities stepped in to defend women when courts failed to intervene, but not always soon enough.37