Chapter 5

A Woman of Pleasure

By the turn of the eighteenth century, technological changes in the production of paper and in printing made the distribution of printed works cheaper and easier, enabling more Americans to get their hands on salacious stories, bawdy illustrations, or outright erotica. This cartoon, published in 1842, depicts a chambermaid resisting an advance from her employer, warning him to “Take care of the Warming pan, Sir.”

As an orphan of fifteen, Fanny Hill made her way to London and sought employment in “any place that such a country girl as I might be fit for.” She found it in what she thought was a genteel home, so “magnificently furnished” that it seemed to belong to “a very reputable family.” Presuming that she had been hired as a domestic servant, Fanny obliged when her mistress’s female “cousin” climbed into her bed. “Her hands became extremely free,” Fanny said, “and wandered over my whole body . . . every part of me was open and exposed to the licentious course of her hands which, like a lambent fire, ran over all my body, and thawed all coldness as they went.” Her libidinal awakening continued on two occasions when she watched women of the house entertain male guests.

Fanny Hill: Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (1748–49), by Englishman John Cleland, was a work of fiction, the outlines of its story likely familiar to many Anglo Americans. Its plot followed a familiar narrative arc. “The Harlot’s Progress” (1721), a series of six prints by the English artist William Hogarth, depicted a country girl’s descent into sex work, poverty, disease, and death. Fanny’s lesbian initiation into sexual adventure likewise echoed scenes in Onania, a book of unknown authorship published around 1716. Onania railed against the deleterious effects of the “solitary vice” among men and women, marking the beginning of a new era of Anglo-American anxieties about masturbation. Like Hogarth’s widely replicated prints, Onania was a consumer item, its vivid descriptions of women’s masturbatory pleasures, including voyeuristic scenes of lesbian sex, a key selling point. Cleland broke with convention by giving his heroine a happier ending. Writing from debtors’ prison in the British East India Company’s settlement in Bombay, he was eager for a commercial hit and perhaps also determined to test the limits of English anti-obscenity laws.1

He created Fanny as a personification of male heterosexual fantasies. When one man disrobed and revealed “naked, stiff and erect, that wonderful machine,” Fanny recalled that “every vein of my body circulate[d] liquid fires.” Fanny brought herself to “at last the critical extacey [sic]; the melting flow into which nature, spent with excess of pleasure dissolves and dies away.” Only when an older man tried to force himself on her did guileless Fanny concede that she was employed in a brothel. Embracing sexual joy, she gave her “maidenhead” to a handsome young man named Charles. Over the next few years he and other men variously kept her as their mistress; she worked at brothels when the men departed or turned her out. Her years of happy whoring ended when Charles returned from years at sea and wed her, a love match achieved despite her past as a woman of pleasure. As a book ostensibly recounting erotic episodes from a woman’s perspective, Fanny Hill instead popularized a male imagining of female sexuality as perpetually eager to submit to a man’s desires.2

Fanny Hill became an international sensation. The original English edition was translated into French and Italian, and copies crossed the Atlantic for sale in Philadelphia. In the early 1800s, printers in Boston, Vermont, Philadelphia, and New York reset the type without concern for errors or embellishments (or the weak and mostly unenforced 1790 Copyright Act), producing the first American editions of one of the most sexually explicit publications of the age.3

Prior to Cleland’s book, depictions of explicit sex in European drawings or essays were usually intended to portray religious or political leaders as in some way indecent. These sexual critiques might titillate, but arousal was not their main purpose. Fanny Hill marked the arrival of a new genre of erotica stripped of any overt message about clerical hypocrisy or political corruption. Instead, Cleland and others invited presumptively male readers to imagine a world in which women craved physical domination.

It was also a far cry from the medical texts that had previously doubled as erotic stimuli. In 1744, the esteemed Northampton, Massachusetts, minister Jonathan Edwards investigated rumors of “lascivious and obscene discourse among the young people.” Adolescent boys and young men in his congregation had apparently read two popular medical texts, from which they learned about female sexual anatomy, orgasm, and the danger of “greensickness,” an illness one book described as the consequence of abstinence. The youths then teased girls in the community about “what nasty creatures they was.” When Edwards attempted to rid his congregation of “bad books,” many members of his community sided with the boys: what they did in private, it was argued, was of no concern to the minister.4

Cleland’s novel, first published just four years after the Northampton episode, contained scenes of explicit sex that surpassed everything else available to English readers. By the early nineteenth century Fanny Hill was no longer quite as exceptional as it had been. Brothels, newspapers, and erotica became regular features of young men’s lives in cities from Boston and New York to Baltimore and New Orleans. Fanny Hill still stood out for its louche explicitness, its mimicry (and mockery) of the conventional novel’s form, and the fact that its fictional narrator was a woman. Seemingly fantastical and accessible at the same time, Fanny offered boys and young men a way to imagine themselves as the admired customers of an adventurous sex worker, a fantasy that had real-world consequences in the early decades of the United States.

Fanny Hill left her rural home to find employment in London, a fictional example of the countryside-to-city path that innumerable young people followed as imperial trade, industrial revolution, and consumer markets transformed life on both sides of the Atlantic. The result was a volatile global economy in which women like Fanny—and the men who purchased her services—increasingly relied on wage work. Wildly fluctuating agricultural yields and currency valuations fostered a capitalist economy dependent on credit and anxious for cash. Sex was one of the commodities on offer.

Enterprising Americans discovered, as Cleland had, that they could profit from portrayals of sexual desire and its satisfaction. Peddlers who trekked along New England’s dirt roads carried copies of Fanny Hill in their satchels and carts, its salacious narrative for sale alongside sewing needles, leather goods, and metal tools. In Concord, New Hampshire, alone, four bookstores kept it in stock.5

The book cost $2, but there were more affordable alternatives for the American reader in search of erotic stimulation. In the 1760s, almanacs printed bawdy poems, rumors of sexual indiscretions, and lewd humor about nonmarital sex. These compendiums of agricultural forecasts and local gossip portrayed both women and men as lusty pleasure-seekers, although they hardly promoted gender equality. Stories of cuckolded husbands mocked men who could not control their wives, and writers warned women to satisfy their husbands lest the men stray. Considering that bastardy rates in Philadelphia during the 1790s were three and a half times higher than they had been from 1767 to 1776, Fanny Hill found an American audience seeking pleasures—and grappling with nonmarital sex’s consequences.6

This sexual conversation included tales of same-sex and otherwise queer pleasures. American booksellers sold homoerotic literature as early as the 1750s, when they began to import a new genre of fiction that simultaneously denigrated same-sex sex and provided readers with voyeuristic descriptions of it. In Philadelphia, Tench Francis operated a bookstore on Front Street, where his July 1754 inventory included what historian Clare Lyons describes as “classical Greek and Roman texts with homoerotic content, Restoration satire employing homoerotic sex and politics, French erotica depicting pairs of women making love and the chroniques scandaleuses of the French aristocracy, English novels with homoerotic and prostitute adventure narratives, and trial reports of criminal prosecutions for sodomy.” One of the books most often checked out of Thomas Bradford’s circulating library in mid-eighteenth-century Philadelphia was Roderick Random, a novel that featured a homoerotic relationship and an effeminate character.7

By the 1820s and 1830s, news of sex workers featured prominently in shoddy newspapers known as the “penny press,” upstart enterprises that relied on daily sales rather than the subscriptions that funded established newspapers. Erotic content also appeared in provocatively named weekly newspapers, such as the Flash and the Rake, which glorified a male youth culture of drinking, gambling, prizefighting, and prostitution—the “sporting life.” Articles about brothels and erotic entertainment gave the names and addresses of notorious sex workers and peep shows, doubling as guidebooks for the adventuresome. In 1841, a New York City paper, Dixon’s Polyanthos, provided a room-by-room overview of the sex workers at a well-known brothel on Leonard Street. “Feminine tastefulness,” the author promised, “and exquisite delicacy . . . are here impersonated in the most attractive form.” Catering to an audience of young economic strivers, the papers’ articles and cartoons mocked wealthy gentlemen as effete buffoons who failed to seduce buxom women. These papers also discussed voyeurism, masturbation, sadomasochism, and female same-sex sex.8

Competition did nothing to dampen demand for Fanny Hill—and no wonder. Cleland’s description of Fanny’s initiation into sex with a man emphasized her desirability as well as the pleasure she took in the act. Narrating her story as a grown woman looking back on her youthful exploits, Fanny recalled how her sexual innocence rendered her white, nubile body irresistible to Charles: “My bosom was now bare and rising in the warmest throbs, presented to his sight and feeling the firm hard swell of a young pair of breasts, such as may be imagined of a girl not sixteen, fresh out of the country, and never before handled.” Yet not even so stupendous a set of breasts could distract Charles from the rest of Fanny’s fair body: “even their pride, whiteness, fashion, pleasing resistance to the touch, could not bribe his restless hands from roving; but giving them the loose, my petticoats and shift were soon taken up, and their stronger centre of attraction laid open to their tender invasion.” The narrative highlighted Charles’s excitement, his thrill in seeing Fanny naked, and his eagerness for sex. It also fixated on both Fanny’s and Charles’s pale complexions; she admired the whiteness of his body—of his forehead, “which was high, perfectly white and smooth,” and of his chest, “whiter than a drift of snow.” These racially specific descriptions made the couple’s eventual union in matrimony both legally possible and socially desirable for readers who read to the book’s abrupt conclusion.9

A “tender invasion” suggests a confusion of care with violation; similar elisions of violence and pleasure recur throughout the novel. By the late eighteenth century, white men in the Atlantic world tended to presume that sex with a woman necessarily involved her resistance and his force. Fanny’s narrative was rooted in this convention: “My fears . . . made me mechanically close my thighs; but the very touch of his hand insinuated between them, and opened a way for the main attack.” Men at the time unselfconsciously bragged of their assaults. A Philadelphian gloated in his diary about “a Ruination at a Soiree,” when he danced with a young woman who “aroused all my passion.” In a scene reminiscent of Fanny’s deflowering, he wrote that this woman “resisted much holding her limbs together, but my flame being up I thrust her vigorously and she opened with a scream—a real joyful fuddle—she screaming much at [Incursion?].” Fanny Hill offered a fantasy of domination, one that validated existing practices and may have enticed other men to see their use of force as a necessary complement to female reluctance. It was a model of male-female intercourse that prevailed in American law by the early 1800s, depicted in Fanny Hill in scenes of delight.10

Fanny’s pale breasts aroused Charles, but forbidden mixed-race sex fired many Americans’ erotic imaginations. American slavery created a marketplace for the description and pursuit of illicit sexual acts. A newspaper story chiding white men who pursued sex with Black women might also titillate readers with descriptions of interracial intimacy. The Daily Orleanian in New Orleans ran stories about notorious “quadroon balls” at which wealthy white men paid for the company of free Black women. Newspapers’ discussions of sexuality could also serve to shame white Southern women who defied white men’s control. The Daily Orleanian published short stories and news articles that denigrated white women who formed “liaisons” with Black men, particularly white women who were arrested for violating the law against interracial sex.11

White enslavers produced an erotic literature premised on Black women’s sexual victimization. Sex was front of mind for many of the men who owned, sold, transported, priced, and negotiated the sales of women. Slave traders calling themselves robbers, as if they were outlaws, chatted in their letters to one another about “fancy girls”—younger and lighter-skinned Black women whom they expected to satisfy their sexual desires. Isaac Franklin, an enslaver in New Orleans, sent a letter in 1834 to Rice Ballard, a well-connected trader: “The fancy Girl from Charlottesville, will you send her out or shall I charge you $1100 for her? Say Quick, I wanted to see her . . . I thought that an old Robber might be satisfyed with two or three maids.” The language of sexual predation became part of a vocabulary for financial jousting. Traders accused business partners of “raping” them out of their profits, and a few referred to themselves as a “one-eyed man,” the enslaver and the penis conflated into a single agent of both sexual and financial domination.12

The first American women’s groups dedicated to eliminating the kind of male sexual license that Fanny Hill endorsed were formed amid a wave of social reform movements in the 1830s. Journals such as the Friend of Virtue and the Advocate of Moral Reform portrayed the libertine rake as a threat to the innocent farm girl whom he seduced, abandoned, and in the parlance of the time, “ruined.” Short stories in the penny press and inexpensive novels featured titles like The Mysteries of Boston, or, a Woman’s Temptation that parlayed the seduction narrative into potboiler fiction. But reformers insisted that the dangers were all too real. The New England Female Moral Reform Society, composed of middle-class white women, argued that male sexual aggression was an imminent threat to women’s virtue. Focused on the eradication of both prostitution and the sexual double standard, they persuaded the Massachusetts legislature to pass a law requiring the licensing of cabdrivers (lest unlicensed drivers abscond with unsuspecting young women) and pushed for a criminal anti-seduction statute. Parents and guardians initiated most seduction cases as civil suits against men who reneged on promises of marriage after having sexual intercourse with their daughters or wards; the members of the Female Moral Reform Society wanted seducers to face prison time. The legislature did not pass the criminal statute these women proposed, but reformers’ efforts added an important counterpoint to the era’s celebration of sex work and sexual coercion.13

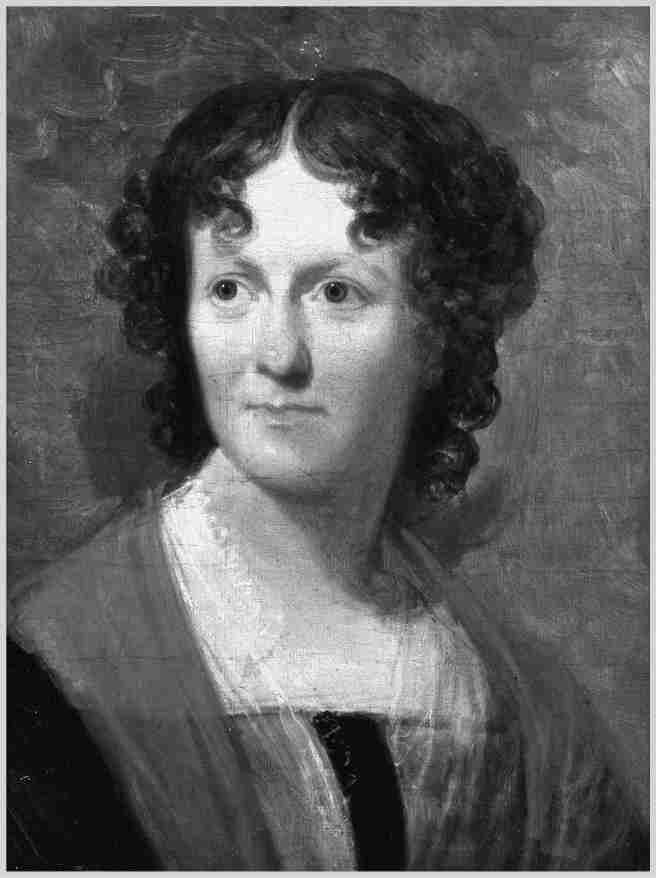

An influential group of health educators challenged these male-centric portrayals of sexual pleasure. From the 1820s through the 1850s, they organized lectures and published books about the pleasures of sex for women as well as for men. Frances Wright was an heiress, radical intellectual, advocate for workers’ rights, abolitionist, and lightning rod for controversy. She belonged to a small but vocal group of secular reformers who preferred the scientific rigor of Enlightenment thought to the pieties of evangelical Christianity. In the 1820s she lectured to large, mostly male audiences as newspaper editors warned that Wright “unsexed herself” by doing so. She wrote in favor of interracial sex and sexual passion (“the best joys of our existence”) and against marriage, but she insisted that women maintain control over their bodies. Knowledge, not legal or religious doctrine, she argued, should regulate passion. “Fanny Wrightism” soon became a vernacular pejorative, a way to mock and discredit a woman who spoke frankly about sex or women’s emancipation.14

Frances Wright (1795–1852) was a freethinker who wanted to circulate scientific information about all aspects of the human experience, including anatomy and reproduction. She opened the Hall of Science in New York City with her colleague and was one of the most outspoken women of her time. Henry Inman, Frances Wright, 1824, oil on canvas, 16 ⅝ × 12 ¾ in., 1955.263, New-York Historical Society.

Using her inherited fortune, Wright purchased a building in lower Manhattan that she renamed the Hall of Science. She dedicated it to scientific knowledge, including the findings presented in the book Moral Physiology (1831) by her friend and fellow religious skeptic Robert Dale Owen. In the book, Owen made a bold case for women’s absolute authority to determine the frequency of pregnancy, a power that he argued was essential if married women were to enjoy sex with their husbands.15

Health reformers risked fines and imprisonment to share information about “physiology” that they believed was essential for adult health. They did so with limited scientific understanding of ovulation or conception. Owen recommended the withdrawal method to control fertility. A Massachusetts physician named Charles Knowlton took a different approach. In his book, Fruits of Philosophy; or the Private Companion of Married People, first published in 1832, Knowlton suggested that women use a postcoital douche to prevent conception. Both men argued that sex was natural and that its enjoyment was healthy. Prosecuted for obscenity under state law, Knowlton was fined and sentenced to three months of hard labor. He defiantly published increasingly explicit editions of his book, with sections that attempted to explain the mechanics of erections and discussed women’s capacity for erotic pleasure separate from reproduction. There was an audience for these books: Fruits of Philosophy was in its tenth edition by 1877.16

Most health reformers of the time focused not on women’s sexual freedom but on Fanny Hill’s intended audience—erotica’s self-pleasuring subject. An anti-masturbation movement preached the dangers of the solitary vice. At first, physicians and moral reformers directed most of their concern toward young men on the make in the nation’s growing cities, where the exercise of self-control might determine not only the progress of their souls but the success of their careers in a competitive market economy. Reformers warned that erotica and prostitutes led young men to abuse their bodies and diminish their chances of becoming financially secure citizens or worthy husbands. Likening sex workers to alcohol, reformers lamented how easily young men became completely preoccupied with the pursuit of sex once exposed to it. They portrayed masturbation and patronage of sex workers as self-indulgent behaviors that spread like contagions among young men and their peers—gateway drugs to complete sexual debasement. In the 1830s, women committed to the cause of moral reform teamed up with male physicians to raise the alarm about the dangers of undisciplined desires that led to “self-pollution.” After the 1850s, reformers advocated what one scholar memorably called a “spermatic economy,” advising young men to moderate their ejaculations lest they deplete their bodies’ “vital energies,” their sperm wasted like dollar bills thrown into the sea.17

The white Christian reformer Sylvester Graham was the most influential anti-masturbation activist in the country. An evangelical Protestant, he believed that individuals must learn to control their inclination to sin. The problem was the overly excited body, for which Graham recommended cold baths, bland diets, and his eponymous crackers, all with the goal of preventing self-pollution. So long as Graham presented these theories to audiences of men, he encountered little opposition.18

Graham risked life and limb to share his presentations about sexual anatomy and masturbation with all-female audiences. It was “reprehensible,” a newspaper editor in Portland, Maine, wrote in 1833, for a man to discuss such subjects with women in the absence of their husbands. More to the point, these men seem to have objected to Graham’s depictions of sexual passion as just as strong in women as it was in men. (Graham’s point, of course, was that women needed to exercise as much restraint as men did.) Rowdy crowds of men and boys gathered outside lecture halls threatening to tar and feather Graham. In 1837, at a Boston lecture rescheduled after threats of violence on its original date, Graham hid “locked up in a nice little room” as female supporters held off an angry mob. He later fled the city after some of these men chased him from his hotel, “maltreating” him along the way. Female reformers who endorsed Graham’s message depicted his adversaries as “libertines, whoremongers, drunkards, and theatre-frequenters.” They concluded that the mob’s supposed outrage over the indelicacy of the subject matter masked the men’s own licentious interests in keeping women ignorant about their bodies and maintaining the idea that sex was a man’s prerogative.19

Proper sexual comportment was a matter of special concern for Black people, given the pernicious sexual stereotypes that suffused American racism. African American educator Sarah Mapps Douglass, a contemporary of Graham’s, approached sexual knowledge as a tool for realizing Black equality. Self-control, she instructed her students, was as available to Black women as to white women. Before she became a sex educator, Douglass was a leader of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, an interracial women’s organization that called for the abolition of slavery and improvements to the living conditions for Black women in their city. For several decades, she ran the Institute for Colored Youth, a school that provided tuition-free education in science as well as literacy; students read anatomy texts and handled specimens from a cabinet of minerals. Douglass herself enrolled in classes in the 1850s at the Female Medical College of Pennsylvania to deepen her knowledge of anatomy and physiology.20

Equipped with the latest theories about the virtues of moderation, Douglass joined a growing chorus of health reformers who argued that the act of masturbation might cause insanity. Her point was not that sexual pleasure was in any way something to avoid. Instead, she taught her students about the naturalness of heterosexual intercourse and of sexual pleasure for both men and women, at least when it was experienced within marriage. She shared this outlook with many leading health reformers of her day, who taught that women, like men, needed sexual release within marriage, to remain physically and mentally healthy. For these reformers, masturbation was a dangerous diversion of sexual energy.21

Fanny Hill: Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure portrays male-female sex as ecstatic—and very, very wet. The night of her first, painful sexual encounter with Charles, Fanny’s awareness of physical injury subsided as “the warm gush darts through all the ravished inwards; what floods of bliss, what melting transports, what agonies of delight, too fierce, too mighty for nature to sustain.” She experienced “the relief of a delicious momentary dissolution, the approaches of which are intimate by a dear delirium, a sweet thrill, on the point of emitting those liquid sweets, in which enjoyment itself is drowned, when one gives the languishing stretch out, and dies at the discharge.” Gushes, floods, melting, liquid sweets, drowning, and discharge appear in many other depictions of orgasm in the novel too.22

A quasi-medical guide written by an unknown English author or several authors, Aristotle’s Masterpiece piqued the erotic imaginations of people on both sides of the Atlantic from its publication in 1684 until the nineteenth century. For average readers during this period, the text provided some of the only printed advice about human sexuality, pregnancy, and childbirth available in English.

These passages in Cleland’s narrative revealed the influence of Aristotle’s Masterpiece, a widely copied and reprinted book whose title originated not with the Greek philosopher but with anonymous writers and editors in seventeenth-century England, possibly working with translations of older Latin treatises about sexual health. With sections devoted to pregnancy, childbirth, and venereal diseases, it was the sort of book that a town physician or midwife might reasonably possess but that was explicit enough to appear improper or lewd in nonexpert hands, to be hidden in chimneys or under mattresses. It contained the most commonly printed advice about human sexuality, pregnancy, and childbirth available from the late seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries in English for the average reader. A compendium of ancient and early modern folklore, it was also a book that piqued some people’s erotic imaginations, much to Jonathan Edwards’s chagrin when it fell into the hands of young men in his congregation. By the late eighteenth century, the version printed in the United States included ribald poetry about marital compromises and wedding-night dilemmas. Aristotle’s Masterpiece went through more editions than all other books on the subject combined, with more than one hundred different printings, including publications in Philadelphia, Boston, and New York.23

Aristotle’s Masterpiece presented an understanding of the human body as composed of four main fluids, or humors. Humoral medicine dated back to the real Aristotle. He taught what some historians have since named a “one-sex model” of human difference, in which the relative quantities of the body’s four humors—blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile—determined whether an individual was male or female. That humoral model led the Greek physician Galen of Pergamon (CE 130–200) to describe men and women as anatomically similar but differentiated by body heat. Men had more hot and dry humors, and for that reason they were usually rational. Women, by contrast, had more cold and moist humors, which made them emotional and weak. The cooler female was an inferior subset of the male; women had men’s genitals, but they were turned inward.24

Physicians and anatomists dismantled this theory in the 1600s, but the idea that fluids regulated human sexuality—and accounted for the conception of new life—persisted well into the nineteenth century. Even as physicians and midwives turned to newer sources of information, chapters in Aristotle’s Masterpiece about overcoming sterility and about the health benefits of frequent, mutually pleasurable heterosexual sex kept these ideas in circulation. The book even contained folklore about heredity, explaining that a child resembled whatever its mother happened to look at during intercourse. Even if she were to have sex with someone other than her husband, conjuring her husband’s image in her mind at that crucial moment would imprint his features on the newly conceived child.25

The “floods of bliss” and “liquid sweets” in Fanny Hill reflect a theory dating to ancient times, and restated in Aristotle’s Masterpiece, that both men and women emit a “seed” during orgasm, the union of which produces a new human life. The authors of Aristotle’s Masterpiece argued that conception required female as well as male orgasm, although they wondered if the “seed” might in fact be an egg, somewhat like a chicken’s. (Scientists did not begin to understand the relationship between ovulation and conception until the early nineteenth century.) Part of the fantasy in Cleland’s book was that his heroine managed to have virtuoso orgasms while miraculously avoiding pregnancy throughout her adventures.26

Aristotle’s Masterpiece served as both a medical guide and a source of erotic amusement for its readers. Earlier versions had cruder woodcuts of naked figures, demons, and “monstrous” births. The illustrations in this nineteenth-century edition maintain the excitement of female nudity while adding the refinement of a sofa and luxurious curtains.

One young American man who almost certainly knew about Cleland’s novel was Richard P. Robinson. For if Fanny’s story had taught men like him anything—aside from the fact of women’s immense enjoyment of sexual intercourse with men of all endowments and predilections—it was that all women, even the ones that he might have thought of derisively as “whores,” longed for romance and owed fidelity to the men who claimed them. Like the fictional Fanny, he left the countryside for the city—in his case, a small town in Connecticut for New York. By 1835, he was an office clerk and lived in a boardinghouse with other young, unmarried men. He spent his evenings attending theaters, where he could afford upper-balcony seats, and drinking in saloons. Robinson’s immersion in what his peers called “the sporting life” acquired a new focus that summer: he saved every penny for trysts with Helen Jewett, one of the city’s most desired sex workers, whom he thought of as his sweetheart. She resided in a notorious yet elegant house on Thomas Street; he was not her only lover. Educated and fanciful, Helen had made her own journey from countryside to city a few years earlier. From their first months of acquaintance, Helen and Richard exchanged passionate love letters. Sex with Helen was not enough for Richard; he wanted her to pledge herself to him alone. Surely, he thought, she owed him that.

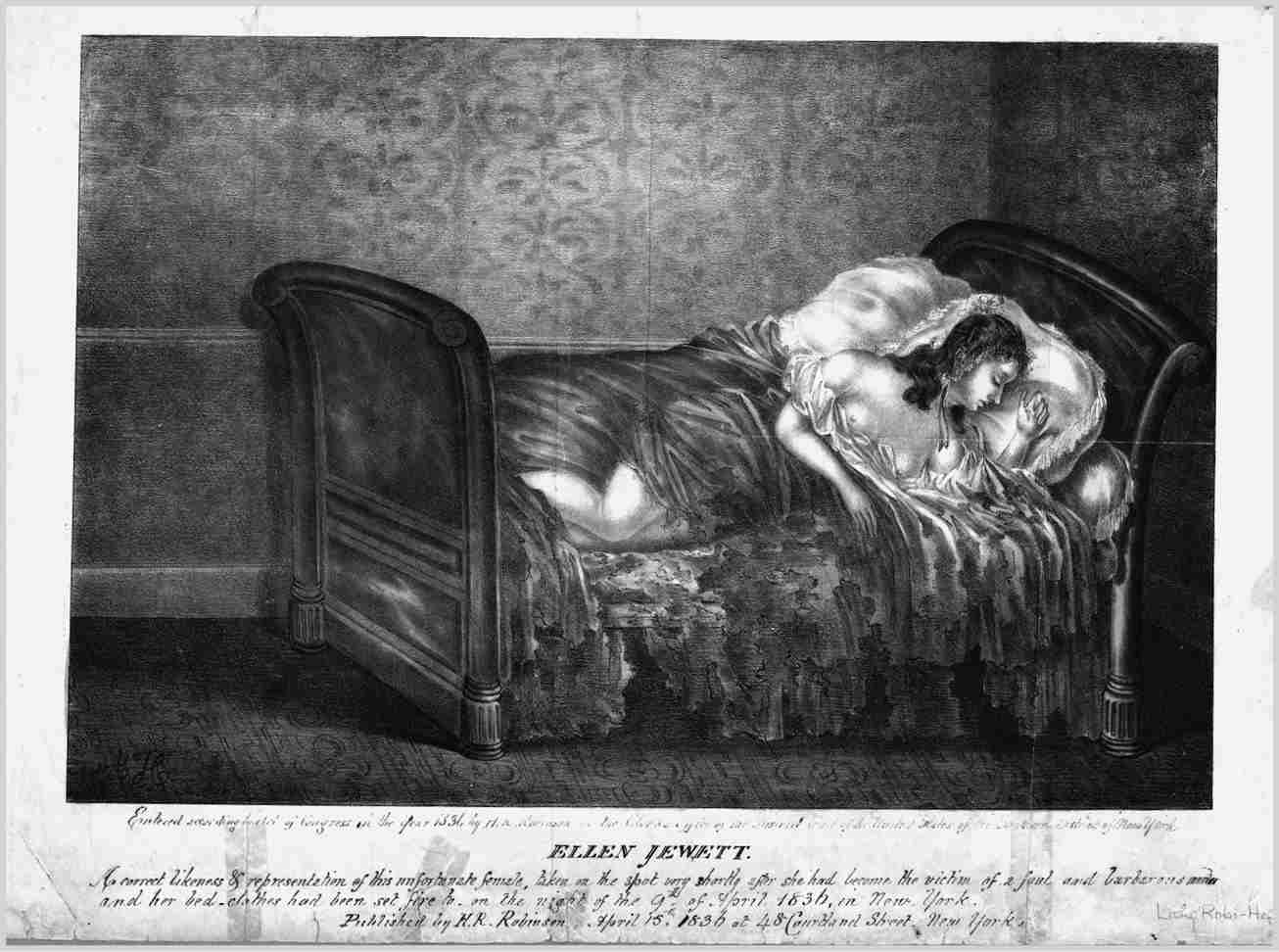

The murder of Helen Jewett, a sex worker in New York City, became a sensationalized news event. Newspapers often misspelled her first name as Ellen, as here in what is described as a “correct likeness & representation” of Jewett immediately following her death on April 9, 1836.

The prime suspect in the murder of Helen Jewett, Richard Robinson was a young clerk in New York City who hoped to become her exclusive love interest. Like many young white men living in America’s cities in the early nineteenth century, Robinson enjoyed the “sporting life” of male-centric and commercially available leisure. He was found not guilty.

Helen could hardly promise Richard constancy, and she may have begun to tire of his jealousy. One bitterly cold Saturday night in April of 1836, the acrid smell of smoke roused the other women of the house on Thomas Street. They found Helen murdered by an ax blow and partly burned from a fire that her assailant had set in her bed. Speaking to police officers who rushed to the scene, women who worked with Helen identified Robinson as the man they had admitted to her room that night. Police arrested him the next morning at his boardinghouse, charged him, and locked him in Bridewell Prison. It was one of the first sensationalized murder trials in U.S. history. The case against Robinson filled newspaper pages for months, inspired erotic images, pamphlets, and novellas, and demonstrated how dramatically the erotic commerce within America’s cities had expanded since the Revolutionary era. By 1837, Richard was himself a character in a quasi-pornographic fictional retelling of Jewett’s murder.27

Helen’s tragic story reminds us that sex work was part of the makeshift economy that many women took part in, and increasingly so by the 1820s and 1830s. Proprietors of brothels and “bawdy houses” rented or owned space in densely populated areas, while some sex workers plied their trade on the street. These businesses blended in with the commercial life and leisure of the city. The Corner House in Baltimore, for example, hosted ladies’ meetings and fundraisers on its upper floors; the basement-level restaurant, meanwhile, functioned as a bawdy house, a place where sex workers from nearby brothels would come for meals and to solicit customers. In Richmond, Virginia, sex workers picked up customers in grocery stores. Theaters permitted sex workers to roam the third tier during performances. Sex work was, in a word, ubiquitous. “The prostitutes in Philadelphia are so many,” a visitor remarked in 1798, “that they flood the streets at night, in such a way that even looking at them in the streets without men you can recognize them.” In New Orleans, white women owned many of the brothels, where they sold the services of enslaved women they kept there.28

Many women who engaged in sex work did so infrequently, to survive personal financial challenges, for instance, but others forged careers. A father’s death, or his violence, led many younger women to leave home and to discover that sex work, while risky, was one of the few occupations available to them. It tended to pay much better than domestic service (which was not without its own hazards, sexual and otherwise). Survival in an emerging wage economy necessitated improvisation. Sex workers in Baltimore occasionally turned to the almshouse for aid, while others sold scraps or bartered sex for materials like yarn and cable that they could transform into items they could sell. Occasionally, women took pride in sex work as a form of entrepreneurial independence. In an echo of the main character in Fanny Hill, a thirty-eight-year-old white woman named Mary Bower told census takers that she was “a lady of pleasure.” Sex work became an integral part of urban economies in the United States.29

Women who provided or enabled interracial sex work faced terrible risks. After a Black woman named Betsey Hawlings was arrested in 1813 at a disorderly house, she was “committed & sold,” suggesting that her arrest may have led to her enslavement. In 1853, Richmond authorities fined a white woman named Jane Wright “for keeping a disorderly and ill-governed house . . . where people of every sex and color congregate and associate by day and night.” When Wright continued to operate her business despite police orders, locals attacked and tore down the building. All that was left was the chimney.30

Cleland opened Fanny Hill’s narrative with her declaration of honesty: “Truth! stark naked truth, is the word; and I will . . . paint situations such as they actually rose to me in nature, careless of violating those laws of decency, that were never made for such unreserved intimacies as ours.” Fanny confesses that she depends on the reader’s sophistication, which would allow them to appreciate her candor: “you have too much sense, too much knowledge of the originals, to snuff prudishly and out of character, at the pictures of them.”31

Far from presenting heterosexuality as unspeakable, however, Fanny Hill and other pornographic productions contributed to a vast conversation about male-female sex. The pretext of scandalous content may have amplified the reader’s excitement about encountering the forbidden. The era’s profusion of written and visual depictions of penis-vagina sex (and of lesbian sex as a form of voyeuristic foreplay) ultimately reassured consumers of erotica that heterosexual desire was a natural part of the human condition. Same-sex sexualities, between men or between women for their own sake, became the unspeakable desires.

Cleland later bemoaned his book’s popularity, not least while facing prosecution in England for obscene libel, but his reputation remained linked to the imagined delights of his titular and indefatigable sex worker. Nor were his subsequent books, including Memoirs of a Coxcomb, which rewrote Fanny Hill from a man’s perspective (though one could argue Fanny Hill itself was already written from a male perspective), any less explicit.32

Fanny Hill remained infamous—and in print—for generations. Affordable prints and texts traversed the nation’s canals and nascent railroad lines, packed into the bags of men heading to Texas and California in the hope of claiming land, fighting Indians, or discovering gold. So, too, did contraceptive cures, condoms, and advertisements for abortion pills and potions. Peddlers, mail-order catalogs, and corner stores sold images and texts that stoked the erotic imagination alongside the more practical implements that reckoned with heterosexual sex’s potential consequences. In 1852, when a man named Richard Hickman came upon piles of personal possessions abandoned by men who had traveled the Platte River before him, he found “books of every sort and size from Fanny Hill to the Bible.”33

The book occasioned the first obscenity trial in the United States, an 1819 case against a Massachusetts printer, Peter Holmes, who was found guilty of selling it and fined. Similar cases followed in New York. One hundred and fifty years later, in the 1960s, Fanny Hill was pivotal to a U.S. Supreme Court case that finally lifted obscenity restrictions on literature. Cleland’s portrayal of Fanny Hill’s fantastical erotic enthusiasm was censored, but its endorsement of rowdy masculine sexual assertiveness endured. Giving voice to women’s sexuality from a female perspective, and apart from the gratification of men’s desires, would require nothing short of a revolution.34