Chapter 8

A Typical Invert

Annie Hindle, a Memphis native, had a successful career on the stage, often playing male parts, and had several female lovers, even marrying one of them. She was in the news just months before Alice Mitchell brutally murdered Freda Ward, whom Mitchell had once hoped to marry.

Alice Mitchell, age nineteen, thought about murder while she sat at a desk in her parents’ home in Memphis in August 1891. Then Alice dipped a pen in ink, set its tip on a sheaf of paper, and proposed marriage to Freda Ward for the third time. Alice first met Freda at Miss Higbee’s School for Young Ladies, an elite, white girls’ academy, from which they had since graduated. Freda, who was seventeen, had accepted Alice’s proposal twice already, but Alice sought confirmation. Alice had given Freda a ring. Originally from Memphis, Freda now lived fifty miles away with her older, married sister in a Tennessee town called Gold Dust. Alice and Freda visited each other when they could and exchanged passionate letters when they couldn’t. “Sweet love,” Freda wrote just weeks earlier, “you know that I love you better than anyone in the wide world.”1

The arrival of August put the lie to July’s promises. Alice pressed the pen into the paper. It had been an awful month. Freda had started to wear a ring given to her by Ashley Roselle, a young man who secured her family’s approval. When Alice responded furiously, Freda begged forgiveness. “I will be true to you this time,” Freda pleaded. Their love reaffirmed, Alice and Freda rehearsed their plans: Alice would put on a man’s suit and get a short haircut to become Alvin J. Ward. (Alice later told Dr. B. F. Turner, a psychiatrist, that shaving would enable a mustache to grow.) Rev. Dr. Patterson, a Memphis minister, would unite Alvin and Freda in marriage. They would catch the next steamboat to St. Louis and live there as man and wife.2

This detail brings us to the question of which pronouns we should use to describe Alice. Alice wanted to be known as Alvin and to be a husband (not a wife) to Freda. The world described Alice as a tomboyish girl who grew up to be a deranged young woman. Today, we might recognize Alice as a butch lesbian or as a transman. Those identifying terms were not available to Alice. Did Alice view a new identity as Alvin simply as a vehicle for being able to marry and form a household with Freda? Or did Alice want to live as a man? I interpret the evidence as pointing toward the latter conclusion, but because Alice did not clarify their plans, I refer throughout the remainder of the chapter to Alice using they/them pronouns.

Weeks earlier, Freda had promised Alice that Ashley meant nothing to her. She marked the riverboat timetables and packed her small bag for Memphis. “I will be perfectly happy when I become Mrs. Alvin J. Ward,” she pledged. (They planned to share Freda’s last name.)3

But now Alice feared betrayal. “Do you remember what I said I would do if you would deceive me?” they wrote. “I love you, Fred,” Alice added, using Freda’s nickname (one used by everyone in her family; it was not intended, at least by most, to have a masculine ring to it), “and would kill Ashley before I would see him take you from me.” Alice contemplated violent retribution: “I had the nerve to price the pistols.”4

A letter intended for a lover instead fell into hostile hands. Freda’s older sister, Ada Volkmar, and her husband, William Volkmar, took their supervisory responsibilities seriously. William suspected that Freda was planning to run away, and he spent one night guarding his yard, Winchester rifle in hand. At the sound of a steamboat whistle, he caught Freda out of bed and fully dressed, her bag packed. She would not take a steamship journey to Memphis after all, nor marry Alice Mitchell. Alice learned about this turn of events in another letter. “I return your ‘engagement ring,’ ” Ada Volkmar informed Alice, fury dripping from the page. “Don’t try in any way, shape, form, or manner to have any intercourse with Fred again.” Ada then wrote to Alice’s mother, telling Mrs. Mitchell of Alice’s “intimacy” with Fred and about the engagement ring.5

Bereft of Fred, Alice felt betrayed. In the late afternoon of January 25, 1892, Alice hid their father’s straightedge blade on their person and went for a ride in Memphis with Lillie Johnson, a friend. Alice had somehow learned that Freda and her sister Josephine Ward had spent a few days in town and were about to return to Gold Dust. Lillie steered her buggy toward the customs house near the riverbank, drawing to a halt when the Ward sisters, walking toward the steamer Ora Lee, came into view. “I have to see Fred again,” Alice told Lillie. Bystanders later affirmed that they heard Alice yell “I’ll fix her!” as they ran down the snow-slicked embankment. Alice caught Freda by the arm and slashed her across the face with the razor. Josephine threw herself between them and pushed Alice to the ground, jabbing Alice with an umbrella. Alice scrambled to their feet and stabbed Josephine with the blade. Freda, frantic and bleeding, tried to escape, but Alice caught up to her. They cut Freda again across the face and then took a fist full of Freda’s hair and yanked back her head for the final, fatal cut.

John Parry’s butcher shop stood not far from the Mitchell household, and he had long teased Alice that they should have been born a boy. Parry saw them smoking cigarettes, playing ball, and riding a stick horse in the street. Alice did not mind being called a tomboy.6

Living as a boy—or, rather, a man—was by 1891 something Alice very much hoped to do. Like many people before them, Alice understood gender as something that could change during a person’s lifetime—something that they themselves could change. Alice would not simply cross-dress to impersonate a man named Alvin; Alice would be Alvin, a husband to Freda, a married man traveling west with their new bride. Both Alice and Freda understood that they would each transform—Alice into Alvin J. Ward and Freda into Mrs. Alvin J. Ward.

The existence of people who wanted to move through gender—to live as a gender different from the one assigned to them at birth—was not novel when Alice Mitchell expressed a desire to become the husband of Freda Ward in the early 1890s. From Thomas/Thomasine Hall in the 1620s and the presence of two-spirit spirit people among Indigenous North Americans, through the gender-crossing figures that animated Thomas Jefferson (“Jeff”) Withers’s comments in the 1820s about his male friend’s attractions to “she-males,” gender-variant people circulate throughout this history. What was new were experts and psychiatrists who seized the opportunity to promote their own theories of sexual “perversion” and gender “inverts.” According to theories of “sexual inversion,” an insufficiently masculine male was at risk of becoming a homosexual; likewise, lesbian tendencies arose in the overly masculine female. An emerging science of sexual pathology shifted the conversation about sexuality and gender in the United States (as it was also shifting in Europe), promoting mental health experts and scientists as sexuality’s foremost authorities. Alice Mitchell’s trial contributed to a new conflation of “queer” desires and gender variance with mental illness and violence, a view that would endure for generations to come.

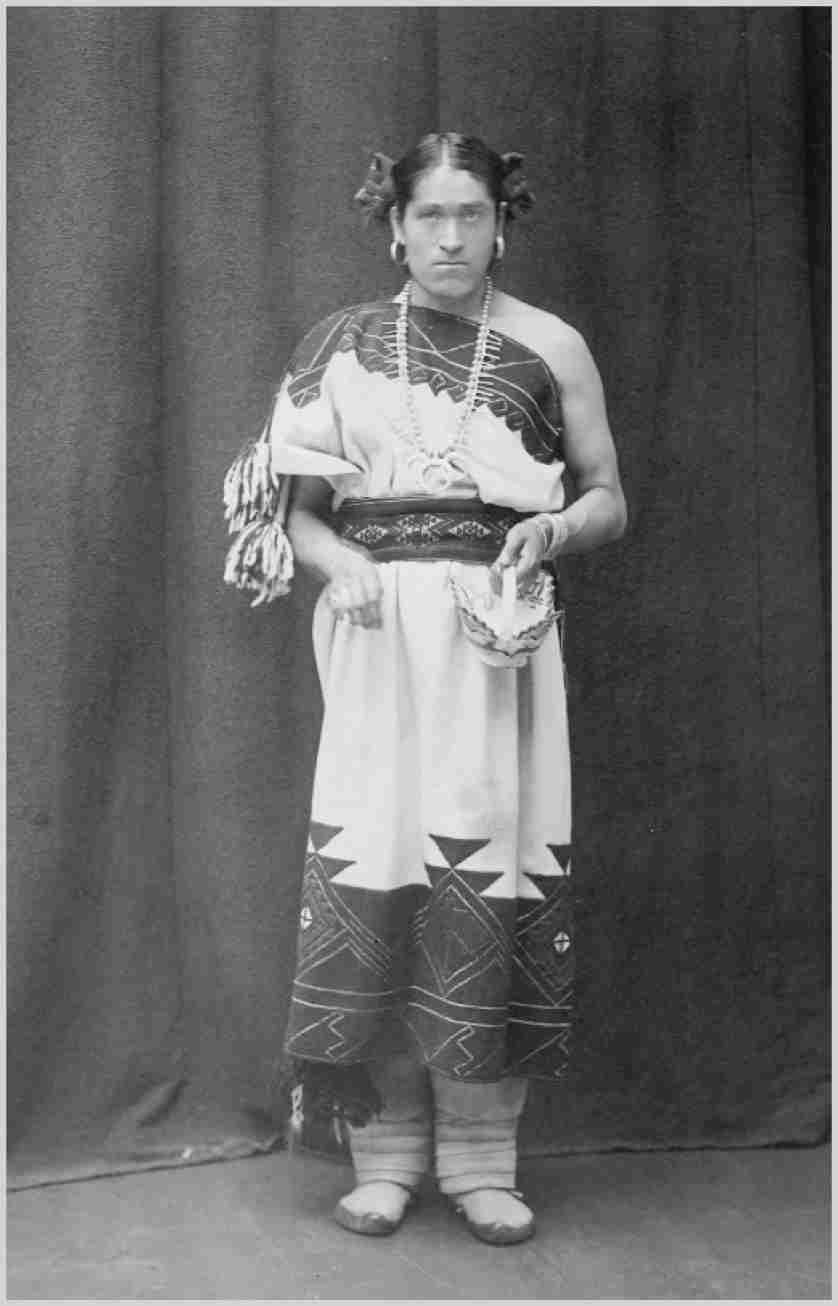

A two-spirit Zuni person named We’wha traveled to Washington, DC, in 1886, where she met President Grover Cleveland at the White House. Assigned male at birth, We’wha was one in a long line of revered two-spirit Native Americans.

Gender-variant people formed relationships that often looked, to outsiders, to be heterosexual. Alices became Alvins and moved on foot, wagon, steamboat, or railroad to a place where they could reintroduce themselves. Cross-gender people were visible and recognized in the second half of the nineteenth century. Newspapers had covered the arrival of We’wha, a lhamana or two-spirit Zuni Pueblo person, in Washington, DC, in 1886. Deeply beloved by her people, this broad-shouldered, six-foot-tall “Indian princess” even visited President Grover Cleveland at the White House.7

Vaudeville theaters and concert saloons featured acts with female and male impersonators. Memphis residents in 1891 might have read about or seen a performance by famed male impersonator Annie Hindle, a fellow Memphian “who played male parts” and whose “inclination was altogether toward women.” Five years earlier, Hindle had married her lover Annie Ryan in a ceremony officiated by a minister. He recognized the love the couple shared but did not notice that both were women. Ryan’s death in December 1891 returned their story to newspapers mere weeks before Freda’s murder. Such cases of “abnormal affection existing between persons of the same sex” made for good copy. The attorney general at Alice Mitchell’s sanity inquest, arguing for the prosecution, in fact asked a defense witness about Hindle.8

A series of new laws made cross-gender self-expression far more dangerous than it had been earlier in the century when neighbors noted Charity Bryant’s masculine habits but generally accepted her relationship with Sylvia Drake. Bans on cross-dressing passed state legislatures as early as 1843, but significant numbers of arrests occurred only when dozens of cities, especially in the South and West, passed separate local ordinances after the Civil War. As American cities grew and expanded their police forces, municipal leaders pledged to tamp down on “indecency” to rid neighborhoods of crime. Sex workers, vagrants, and cross-dressers were increasingly vulnerable. Anglo-American lawmakers had long worried that someone might cross-dress to evade identification while committing a crime or, if a woman dressed as a man, benefit from employment or other privileges to which she was not entitled. But the laws passed in U.S. cities in the mid-nineteenth century were specially focused on preventing “lewd” or “disorderly” public conduct.9

These laws proliferated despite ample evidence that many people arrested for “cross-dressing” were not doing so in commission of a crime or fraud but to express their authentic self. Charley Parkhurst was born in New England in the early 1800s but journeyed to Santa Cruz, California, by 1856, where he had a fifteen-year career as a stagecoach driver. Across routes that stretched from Oakland to San Jose, Parkhurst made a living in a man’s occupation. Only upon his death in 1879 did neighbors discover that he did not have male sex organs. Most individuals who lived as a sex different from the one assigned to them at birth went about their daily routines without attracting any police response. Parkhurst would almost certainly have rejected any suggestion that he “cross-dressed.”10

A white seventeen-year-old girl’s murder in broad daylight by her lover captivated Americans and became grist for newspaper reports across the country. Violent deaths of white girls and young women from “good” families often grabbed headlines. The youth and gender of Freda Ward’s killer, and the details of Alice and Freda’s relationship, made this story a sensation. It was Alice, more than Freda, that distinguished the event, presented in newspaper stories as something of a novelty as a female suspect (as all the papers described Mitchell). In January 1892, Lizzie Borden was a relatively unknown single woman in her thirties living quietly at home with her father and stepmother in Fall River, Massachusetts, not yet famous for her hatchet.

Alice’s murder of Freda drew attention to emerging theories about the relationship between gender, sexuality, and inherited criminality. Late-nineteenth-century Americans looking for explanations of illicit behavior often turned to theories of racial difference. Scientists examined cranial measurements to determine personal character, including the likelihood that an individual would commit a crime. Social scientists promulgated loose adaptations of Darwinian theories of evolution to argue that darker-skinned people resided lower on the evolutionary ladder, that both “lunacy” and poverty were inherited traits, and that “Anglo-Saxon” men occupied the highest strata of mental and moral attainment. Within twenty years, the emerging science of eugenics would be applied widely to understand all people’s “fitness” and “traits.”11

Neither criminality nor insanity were ever supposed to describe a graduate of a place such as Higbee’s School for Young Ladies. Intense female friendships remained common at all-girls schools and colleges, much as they had for the students who climbed into Addie Brown’s bed at Miss Porter’s School in the 1860s. Classmates asked one another to dances (where one partner typically wore a man’s suit), sent flowers, and wrote passionate love letters. A student scrapbook from the H. Sophie Newcomb College of Tulane University for “white girls and young women” included a photograph of a student’s room, its two twin beds pushed together. “Smashing,” as it was known in the northeast, or “chumming” as white Southerners called it, encouraged newer students to accept the attentions of an upper-class student. With rituals that closely mirrored heterosexual courtship, and even with few surviving records attesting to specific sex acts, the erotic possibilities remain obvious.12

The first generation of women to graduate from college in the 1870s and 1880s confronted outrage not because they had intimacies with one another but because of suspicions that their educations had damaged their reproductive systems. Psychologist G. Stanley Hall warned that female graduates would be “functionally castrated” and would “deplore the necessity of childbearing.” Many graduates of women’s colleges did indeed choose not to become mothers; 53 percent of Bryn Mawr students from 1889 to 1908 never married, and many college-educated women never had children. At a time when universities and many professional organizations refused to hire married women, remaining “single” (if possibly partnered to another woman) may have also been a strategy for employment and access to male privilege. In the early twentieth century, a study of unmarried college graduates found that 28 percent from women’s colleges and 20 percent from coeducational institutions had had a queer sexual relationship.13

Freda’s and Alice’s parents sent them to Higbee’s School for Young Ladies unconcerned with cross-dressed dance partners or Boston marriages. They fully expected their daughters to marry men after graduation. Alice was a distinguished student from a prominent family. They won medals for their accomplishments in music and mathematics (although one of the psychiatrists who examined Alice insisted that they were “a slow pupil at school”). Newspapers identified Alice’s father, George, as a “wealthy and honored citizen,” a senior partner of a furniture company and brother to a “millionaire furniture manufacturer of Cincinnati.” Freda’s family was more tenuously middle-class; her father, Tom Ward, had been a machinist and now made his living by “planting and merchandizing” in Gold Dust.14

Freda’s family responded to the discovery of Alice’s love letters with fury but not with violence. They already knew that Alice and Freda hugged and kissed each other, because they had either seen or heard about it. Had Freda carried on an affair with an African American man, however, the response would likely have been assault, not an irate letter from Ada Volkmar. By the 1890s, reactions to sex across the color line were far more intense (and, often, vicious) than the disdain that met same-sex or queer relationships.

During the early days of Reconstruction (1865–1877), several Southern states, with new, Republican legislatures, repealed laws against interracial marriage. (Tennessee did not.) Once white-supremacist legislators succeeded in using terror and disenfranchisement to return the South to nearly all-white rule, these states reinstated their “anti-miscegenation” laws. Even mixed-race couples who married during Reconstruction in states that had briefly legalized interracial marriage faced the possibility of arrest. Western states like Oregon and Nevada added Chinese people (or, as California’s law stipulated, persons with “Mongolian” blood) to their interracial marriage bans. By 1900, most U.S. states, including Indiana, Delaware, every Southern state, and most of the Mountain West, banned interracial marriage.15

That antipathy was pervasive. Newspapers in Memphis documented 81 murders of white women by white husbands and lovers in 1892, yet the papers more often portrayed unrelated Black men as the most lethal threats to white women’s safety. They ran stories of white men like Richard L. Johnson, who died defending his “charming daughter” from “the brutal blacks” who assaulted them. Time and again, whites across the South made allegations of attempted rape or rape against Black men who had achieved a modicum of economic or political power. Between 1882 and 1929, white mobs tortured and murdered more than 3,000 Americans of African descent accused or convicted of a crime.16

Just two months after Alice killed Freda, in March 1892, white men murdered three Black men whose store, the People’s Grocery, competed with white-owned businesses. Judge Julius DuBose, who presided in this case as he did in Alice Mitchell’s trial, believed that Black people were conspiring to incite violence in reaction to the murders and urged white Memphians to take up arms. Ida B. Wells was still a young woman at the time, a journalist who wrote for Memphis’s Black newspaper, the Free Speech. Tommie Moss, one of the men lynched by the white mob, was her close friend.17

The deaths of Moss and two other Black men at the hands of a white mob inspired Wells to write one of the most incendiary editorials ever printed in the United States. Wells researched the circumstances surrounding the lynching of Black people and turned up multiple instances in which Black men accused of rape had been in consensual relationships with white women. Wells concluded that white families sometimes used rape allegations against Black men to allay gossip about what would otherwise constitute white women’s scandalous sexual behaviors. As she wrote in an editorial printed on May 21, 1892, in the Free Speech, “If white men are not careful . . . a conclusion will then be reached which will be very damaging to the moral reputation of their women.” She then left Memphis for a three-week trip to Philadelphia and New York City, where she had plans to meet with leading figures in the movement for African American civil rights.18

Wells never returned to Memphis, lifelong exile from her home city the price for daring to impugn the sexual reputations of Southern white women. Soon after her departure, a white mob ransacked the offices of the Free Speech and threatened to attack anyone who attempted to publish the paper again. Her former neighbors in Memphis sent word that white men were surveilling her home and threatening, she wrote, “to kill me on sight.” Wells persisted, writing a series of essays about lynching for Black newspapers in the North, which she compiled into a pamphlet, Southern Horrors (1892). Lynchings of Black men for alleged rape, she argued, reflected not actual violence against women but the toxic sexual double standard of Southern “chivalry.” Southern white men defend white women’s “honor,” Wells wrote, while doing nothing to prevent or hold anyone accountable for the rapes of Black women and girls. Racism, not sexual violence, thus motivated the vigilantes who attacked Tommie Moss and other Black victims of lynching.19

The white women of Memphis, meanwhile, were appalled by the murder of Freda Ward, one of their own, and clamored for justice. Alongside reports about Freda’s murder, newspapers carried cautionary tales of young women whose boarding school or rooming house infatuations turned into dangerously passionate attachments. This was a dramatic departure from what had, until then, been presented as benign schoolgirl crushes. Financially secure white families expected women in their families to marry well, or, at the very least, cultivate domestic spinsterhood in the home of a married relative. They would reside among white people, socialize with members of their social class, and remain sexually virtuous. Now, however, the parents of such ladies had reason for concern.20

George Mitchell had the means to hire three attorneys to defend his daughter. They convinced the judge to forestall prosecution for murder until an inquest could determine if Alice was mentally competent to stand trial. That July, five months after the murder of Freda Ward, white Memphians packed the Shelby County Courthouse, where Judge DuBose presided over hearings to determine whether Alice Mitchell suffered from “present insanity.”21

To prove that Alice was not competent to stand trial, the defense called on experts who connected Alice’s erotic and gendered desires to a disordered mental state. F. L. Sim, an infectious-disease specialist at Memphis Hospital Medical College, explained that Alice’s mental illness was hereditary. It had been passed down from their mother, who had experienced “puerperal insanity,” today known as postpartum depression or psychosis, which had required a two-month hospitalization after the birth of her first child. The infant died soon after birth, and Mrs. Mitchell’s “mind became unbalanced by the news,” prompting a “mental aberration.” Sim also cited the claim that masturbation could cause insanity, an idea that dated back at least as far as the physiology lectures of Sylvester Graham in the 1830s and 1840s. He speculated that “self-abuse or excessive sexual indulgence” would certainly have weakened Alice’s nervous system. Another physician consulted for the insanity inquiry concluded that Alice suffered from an “unnatural and perverted passion” and, at the time of the murder, was afflicted by “hysterical mania.”22

For some experts, it was Alice’s stated interest in marrying Freda that proved their insanity. Distinguishing criminality from mental illness, these commentators explained that the presence of sexual depravity did not necessarily indicate insanity. Instead, Alice’s confidence that they could marry Freda proved that Alice did not comprehend the mechanics of sexual intercourse: as the Medical Superintendent of the Central Hospital for the Insane of the State of Tennessee explained, the planned nuptials provided “evidence either of a gross delusion or the conception of a person imbecile or of a child” who lacked an understanding of “the connubial state” within marriage. The superintendent’s statement erased the possibility of lesbian or queer desire, defining sex as only male-female vaginal intercourse.23

One physician concluded that Alice suffered from “erotomania,” an aggressive female sexuality that these medical experts associated with darker-skinned people and sex workers. His statement reflected an emerging science of sexuality that drew from anthropologists’ observations of “primitive” peoples in Africa and the Pacific Islands. Evolutionary theories about the progress of civilization placed Anglo-Saxons at the peak of racial maturity and sexual civility. American sexologists viewed their own presumptive gender norms—of feminine women and masculine men—as evidence of the triumph of a superior American culture over that of the Native peoples who originally populated those lands. A third-sex person such as We’wha symbolized a vanishing, inferior past.24

Sexological studies portrayed “savage” women as both physiologically distinct and threateningly sexual. F. E. Daniel, a physician in Austin, Texas, recommended “asexualizing” criminals because, he argued, “perversion” was not only hereditary but more common among “the lower classes, especially negroes.” It’s not certain how many Black women were subjected to clitorectomies in U.S. prisons or asylums. What’s clear is that when physicians associated Black women with larger than average clitorises (and thus with intense sexual desires), they gave scientific authority to longstanding racist stereotypes.25

This logic led sexologists to conclude that queer desire was proof of a primitive sexuality. Dr. P. M. Wise at the Willard Asylum for the Insane in New York circulated a case study about one person whose queerness and gender nonconformity were especially well documented. Lucy Ann Lobdell wrote a memoir, The Female Hunter, in 1855, but they later dressed as a man, pursued men’s labor, and sought relationships with women as a person named Joseph Lobdell. Wise attributed Lobdell’s sexual aggression to an enlarged clitoris. In “A Case of Sexual Perversion” (1883), he described Lobdell as a “Lesbian,” the first time an American publication used that word to describe a woman who sexually desired women. Such intense, atavistic sexual desires were out of place in a person such as Alice. By virtue of Alice’s race and class status, their sexuality and gender nonconformity disrupted the South’s social order. Alice was, to their contemporaries, an elite white woman displaying the sexual passion that medical elites believed was more often found among “savage” women and sex workers.26

An indication of Alice’s supposed savagery was their “bisexuality,” a newer term that connoted the presence of both male and female sexual characteristics. The American physician James G. Kiernan, Secretary of the Chicago Academy of Medicine and widely considered an expert on sexual science, explained in 1888 that bisexuality remained in some people as an evolutionary vestige from more primitive stages of development; the more civilized a group of people, the more they expressed distinct male/female gender differences and different-sex sexual attractions. Kiernan and others classified Native American, African, and lower-class women as hypersexual, a trait these scientists, like Wise, associated with an exceptionally large clitoris. They adopted the term “female inverts” for people like Alice (and Lobdell) and diagnosed both inverts and sex workers with degenerative nymphomania. Such people were more likely to masturbate, commit crimes, and go insane.27

Many contemporary theories about the psychology of queer desire and gender variance originated in Germany. The German lawyer Karl Heinrich Ulrichs coined the term “uranism” to describe a “contrary” sex drive in 1864. Ten years earlier he had been forced to resign a civil-service job after his supervisors learned that he had engaged in homosexual behavior. Ulrichs set out to prove that his erotic interest in men was natural, innate, and benign. “Urnings,” he wrote, were people of an intermediate, third sex, their male bodies and female psyches leading them to desire same-gendered people. In an era when Germany and Britain enforced their anti-sodomy laws, Ulrichs and other physician-reformers explained that “contrary sexual feeling” was not criminal but natural. These traits were an individual inheritance, passed down through generations. Sexologists in the United States adapted ideas about “urnings,” but when American medical journals discussed Alice Mitchell as an exemplar of sexual inversion or “urning,” they did so to prove that Alice was a pervert.28

Lawyers in the Mitchell insanity trial could draw upon new theories about “normal” psychology—and the perverse manifestations of degeneracy. German physician Richard von Krafft-Ebing based his hugely influential book, Psychopathia Sexualis, on interviews with hundreds of clients from his private practice and of inmates in asylums. He concluded that people with underdeveloped nervous systems had uncontrollable sexual appetites. The book, which went through at least twelve editions following its initial publication in 1877, detailed perversions of “normal” sexuality, from sadism and fetishism to homosexuality. In his later years, Krafft-Ebing conceded that he had been in error when he labeled contrary sexual feeling a psychic degeneracy; same-sex desire, he now believed, was compatible with mental health. American psychiatry, still, did not agree.29

The defense lawyers for Alice Mitchell constructed their case for insanity by characterizing Alice as a person who had suffered throughout their life from a distorted gender identity, even if they didn’t use those terms. As a young child, the lawyers explained in an account that appeared in a local paper and a medical journal, Alice “was fond of climbing” and preferred to spend time with their brother rather than their sisters. Men of Alice’s cohort, the experts opined, recognized Alice’s psychological impairment as the reason Alice turned them down: “[Alice] was regarded as mentally wrong by young men toward whom [they] had thus acted.” Charles Mundinger knew Alice’s family well and had always found Alice peculiar—especially after Alice “failed to pay as much attention to him as he expected.” Lillie Johnson’s brother, James, testified that when he asked Alice to dance with him, Alice refused; “[they] seemed to care nothing about young men.”30

William Volkmar, by contrast, wanted Alice convicted of the murder of his sister-in-law. He said that Alice “never impressed him as being a crazy person” and, while “tomboyish,” flirted relentlessly with men. This account was an outlier. It may have reflected Volkmar’s personal motives more than a faithful recollection of Alice’s behavior. Sexual interest in men would disprove the defense’s insanity case and leave Alice vulnerable to murder charges. Other witnesses testified that Alice often purchased cigarettes, more proof of Alice’s sexual or gender deviance; respectable, feminine women did not smoke, at least not in public, until the 1920s. Alice’s “fondness for outdoor sports,” their attorneys emphasized, was another consequence of “an unusual mind.”31

It was thus Alice’s notion that they could become Alvin, more than their presumably premeditated killing of Freda, that led an all-male jury to declare them insane. Alice and Freda’s relationship had not led anyone to arrest or otherwise castigate them for sexual deviance, but Alice’s criminal behavior ended up giving a boost to medical theories that stigmatized queer people. In the ensuing decades, those theories provided justifications for laws and policing strategies predicated on the idea that sexual “deviants” were also mentally unstable. The same physician who had ordered Alice’s mother confined to an asylum after the death of her first child in St. Louis thirty years earlier also weighed in about the connections between sexuality and mental health. He wrote that the “unnatural affection existing between Alice Mitchell and Freda Ward” confirmed that Alice was “what is known in forensic medicine as a sexual pervert.”32

On July 30, 1892, the jury declared Alice insane and remanded them to the care of an asylum in Bolivar, Tennessee. Before Alice left Memphis, they stopped at the cemetery, leaving flowers on Freda’s grave. Newspapers now depicted Alice as consummately feminine, domesticated by their incarceration, playing the French harp from the asylum balcony.33

Alice lived only six years at Bolivar. They died there of tuberculosis in 1898, never having set foot outside the institution’s grounds since their confinement. More than three decades later, one of Alice’s attorneys provided a more sensational, if possibly true, cause of death: suicide by jumping into the Bolivar water tower.34

Had Alice’s life worked out otherwise—if they had never found their father’s knife or reached the mental health crisis that led them to commit murder—they would have entered adulthood in a world full of increasing danger but also increasing possibilities for trans and gender-nonconforming people. Some women and transmen who desired intimate relationships with women had started to take on what would many decades later be called “butch-femme” roles. In contrast to the Boston marriage, which presented a genteel, asexual image to the public, the “mannish” lesbian was a woman who did not conform to gender expectations and was assertively interested in sex with other women. Their masculine qualities became case studies of “inversion” for sexologists who interpreted homosexuality as a mismatch of gender identity and sexual desire. These lesbians renounced heterosexual expectations of their assigned sex or social station.35

Or Alice might have slipped out of her parents’ house one night, boarded that steamship north from Memphis, and done what a truly unknowable number of people did: show up in a new town or city, where no one knew them, and introduce themselves, at last, as a man, hoping someday to marry and settle down. Towns, smaller cities, and even rural areas seem to have been particularly appealing places for transmen to reinvent themselves in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Perhaps Alice might have gravitated toward the androgynous style popular among middle-class and wealthier lesbians. Parodied in the press as unsexed women with overly active brains and irrational anger about their disenfranchisement, this “New” American woman had a solid education and the gall to defy expectations for delicacy or dependency.36

These possibilities had all been foreclosed for Alice, but Alice’s case lived on. British sexologist Havelock Ellis discussed Alice Mitchell in the second volume of his famous book, Studies in the Psychology of Sex, entitled Sexual Inversion (1901). Alice was, Ellis wrote, “a typical invert of a very pronounced kind,” and he described them as the prototype (in gender presentation, not in murderousness) of the masculine lesbian. He insisted that sexual desire and gender identity were inborn, or congenital, rather than traits acquired from bad habits like compulsive masturbation. Another physician studying the case wondered whether the theory of sexual inversion exculpated Alice Mitchell for the murder of Freda Ward: If Alice’s desire for Freda reflected a “sexual condition” rather than a perpetually disordered mind, then they deserved the same clemency that judges and juries afforded to male defendants in heterosexual love murders who claimed temporary insanity. These theorists of sexual inversion insisted that homosexuality was a special but harmless trait, like synesthesia, and thus not a vice or weakness of character. Ellis had hoped to remove stigma from male and female homosexuality, but his concept of inversion helped popularize the argument that feminism reflected the interests of lesbians and mannish women.37

Ellis took issue with Krafft-Ebing’s theory that homosexuality could be inherited or acquired, and he also disputed Sigmund Freud’s argument that Eros’s impulses resided within the subconscious. Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, postulated that sexual “degeneracy” lurked within even the most educated, elite individuals from “good” families. All people, he explained, contained a “polymorphously perverse” sexuality in infancy, by which he meant that a person’s innate sexuality had no predetermined object. Instead, children’s experiences of maternal affection or rejection determined whether they would mature into well-adjusted heterosexual adults or develop sexual “neuroses.” Freud theorized, for instance, that boys who were too attached to their mothers would identify too closely with feminine qualities and, like their mothers (presumably), seek male rather than female sexual partners. Heterosexual desire should be the result of an individual’s subconscious resolution of adolescent bisexuality; homosexuals’ psychological condition, in this theory, remained developmentally stunted. Freud and his colleagues argued for psychoanalysis, or talk therapy, rather than any surgical or endocrinological interventions, as the only way to help their patients become psychosexually mature.38

Theories abounded. The psychiatrist James Kiernan explained bisexuality to his professional colleagues as one of the consequences of “normal” women falling under the persuasion of the masculine women leading the suffrage movement. Sexologists, he wrote in 1914, do not “think every suffragette an invert,” but “the very fact that women in general of today are more and more deeply invading man’s sphere” was “indicative of a certain impelling force [sexual inversion] within them.”39

Many of the leaders and rank-and-file of the suffrage movement in fact had intimate relationships with women, wore gender-nonconforming clothes or hairstyles, or otherwise rejected conventional femininity and heterosexuality. As the pressures of winning the right to vote intensified, movement leaders urged all suffrage women to conform to conventional expectations for their gender. Women who had led more openly gender-nonconforming or queer lives began to hide these aspects of themselves. They certainly faced relentless hostility from the broader public. J. W. Meagher, a physician, explained in 1929, “The driving force in many agitators and militant women . . . is often an unsatisfied sex impulse, with a homosexual aim.” Importantly, Meagher was a supporter of “companionate marriage,” an idea popular in the 1920s that emphasized the sexual pleasures of heterosexual love. The new configuration of identities treated same-sex desires as a threat to male-female relationships.40

What to do with the sexual pervert—lock them away, like Alice? Assume that insanity is hereditary and sterilize people such as Alice so that they would not give birth to anyone as “unfit” as they were? Educate other young people about the evils of lesbianism? Cleanse American bookstores and libraries of the sorts of salacious materials that might awaken depraved impulses in an impressionable mind? Or blame someone else—someone darker skinned, or poorer, or more marginal—for corrupting “American” morals? Nothing was off the table.