Chapter 9

Obscene and Immoral

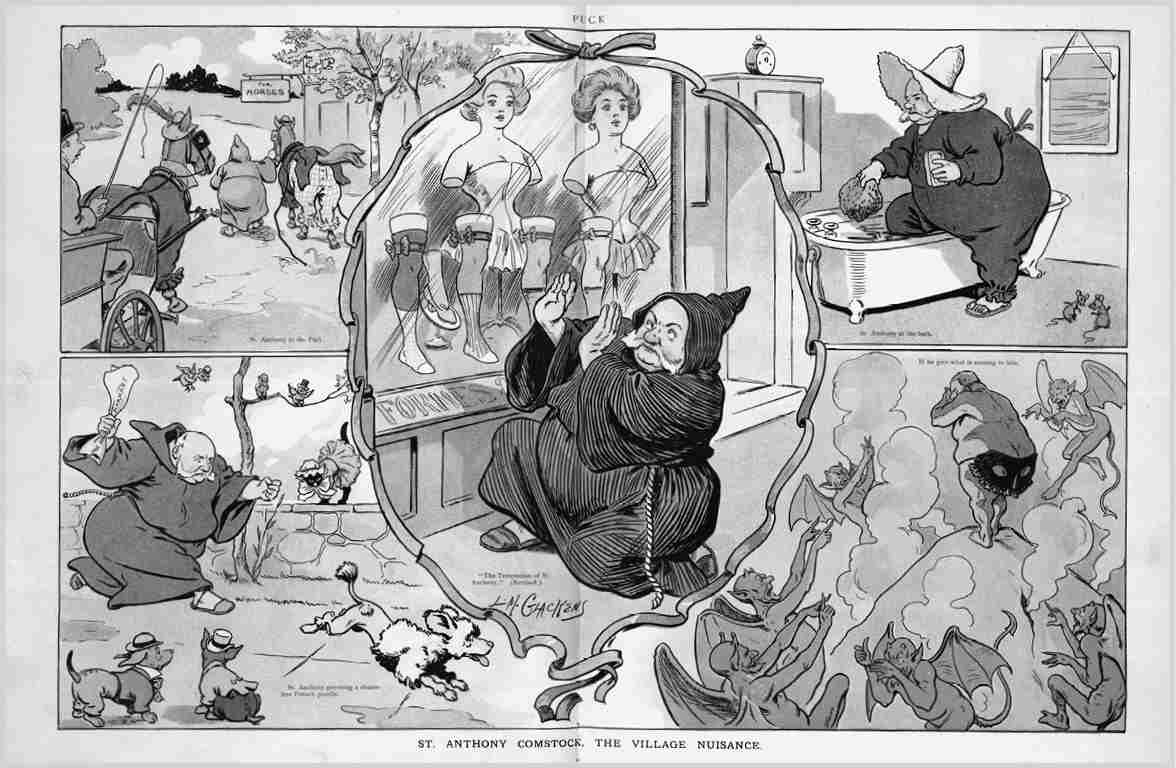

Anthony Comstock devoted his adult life to battling obscenity. His endless crusade against all sexual subject matter is the subject of this satirical 1906 cartoon, “St. Anthony Comstock, the Village Nuisance,” by L. M. Glackens, which portrays Comstock as a monk who cannot bear to undress himself for a bath and physically recoils from depictions of the female body. As suggested by the illustration in the bottom right, which shows a naked Comstock confronting the fires of hell, many Americans strongly rejected his views.

In December 1872, a thirty-year-old man named Anthony Comstock boarded a train bound for the nation’s capital with a suitcase full of porn. His dossier was a catalog of the images and texts that he believed proved the necessity of stronger federal anti-obscenity measures. Several states already had anti-obscenity laws on the books when Comstock, a devout Protestant, launched his pornographic road show, but federal laws were weak. The Tariff Act of 1842 permitted customs officials to seize “obscene or immoral” prints and pictures at the border but did nothing about interstate commerce. The anti-obscenity movement that Comstock led for fifty years was something entirely different: an unprecedented call for the federal government to regulate erotica produced and circulated within the United States.1

Comstock’s train ride to Washington ended in victory. In 1873 Congress passed the “Act for the Suppression of Trade in, and Circulation of Obscene Literature and Articles of Immoral Use,” soon known colloquially as the Comstock Act. The law prohibited sending “obscene, lewd, or lascivious” items through the U.S. mail. It contained the broadest definition yet of the kinds of materials that could be banned and seized by inspectors, including “any obscene book, pamphlet, paper, writing advertisement, circular, print, picture, drawing or other representation, figure, or image on or of paper or other material, or any cast, instrument, or other article of an immoral nature.” Dildos and paintings of classical nudes hanging in art galleries were comparably forbidden. The law defined both pornography and physiological education guides as equally obscene. These offenses were misdemeanors, but a conviction could carry a sentence of six months of hard labor or a fine of $100 to $2,000.2

Comstock’s definition of obscenity included not only erotica (broadly defined) but contraception and abortion too. The law banned from the U.S. mail “any drug or medicine, or any article whatever, for the prevention of conception, or for causing unlawful abortion” and made it illegal to write, print, or advertise “when, where, how, or of whom, or by what means” one could obtain them. It empowered government agents to search out and destroy condoms, pamphlets about contraception, or tonics to induce miscarriage, and to prosecute abortionists and sex educators. Comstock associated contraceptive devices and abortifacients with prostitution: all “decent” women would have sex only within marriage, and thus would have no reason to resort to measures more often found on the fringes of society, the demimonde of prostitutes, gamblers, and thieves. Prudish, sanctimonious, and cruel, Comstock succeeded in convincing the federal government to impose his values on all Americans’ sexual behavior and speech.

Yet twenty years later, Comstock stormed out of the Egyptian Theater on Cairo Street, a destination at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, appalled by what he considered an obscene performance that he was unable to shut down. Cairo Street was located on the “Midway Plaisance,” a mile-long “bazaar of all nations” that boasted exhibits of “foreign” cultures as well as popular entertainments. Its reconstruction of an Egyptian thoroughfare attracted nearly as much excitement as the gigantic Ferris wheel nearby. Tourists came to look at men wearing turbans, fezzes, and tunics and lounging in front of stores.3

The Egyptian Theater on Cairo Street became especially famous (infamous, to some). The main show featured dancers named Fahrina and Nebowa, among a dozen other women wearing modest if flowing dresses, who tucked their pelvises and circled their hips as a few men accompanied them on castanets, tambourines, and flutes. Their performance was, according to a Chicago reporter, “weird and indescribable.” In one act, a performer placed two champagne glasses on her bare midriff, contracting her abdominal muscles so precisely that the glasses clinked. Lifted skirts revealed a leg clothed in a loose pant, not bare, but the suggestion of nudity was enough to titillate. Middle Eastern women had a longstanding association in the American imagination with nonmonogamous, “exotic” sexuality; at the fair, they performed not just a dance but an erotic fantasy. Promoters advertised the dancers’ “hootchy-kootchy” or “cootch” dance, also known as the danse du ventre, and soon it was the talk of both the fair and the national press.4

The dancers’ demonstration of female sensuality, and the enjoyment of that display by men and women alike, encapsulated for many white Americans the essence of what made something “foreign” or “un-Christian.” Anthony Comstock watched the dance not with fascination but in apparent horror. A sex radical and mystic named Ida Craddock, meanwhile, was enraptured. Their lives would soon intersect.

Comstock targeted people who sold contraceptives, provided abortions, and wrote about sexual health. He went after free lovers too. One of the least popular yet most influential figures in this book’s history, Comstock was regularly ridiculed. A black market for contraceptives evaded the law’s reach. Yet Comstock had an unquestioned influence over the way Americans spoke about, wrote about, and legislated sex. The people who defied him, including Craddock and birth-control reformer Margaret Sanger, often paid a steep price, but their insistence on the necessity of candor—its erotically liberating and even life-saving power—is one of his legacies.

Comstock was right about one thing: erotica was everywhere. Print editions of Fanny Hill and its saucy illustrations were only the start. Since the 1830s, advances in the vulcanization of rubber had enabled the mass production of condoms, cervical caps, dildos, and other sex toys. Improvements in printing and in mail delivery made it possible for rural residents to order contraceptive devices from circulars as niche as the Grand Fancy Bijou Catalogue of the Sporting Man’s Emporium. The invention of photography soon created new categories of erotic images. Stereoscopes held two copies of an image at a fixed distance from the viewer, rendering a kind of three-dimensional visual experience. Such images often depicted famous buildings from European capitals, but many others showed sexual scenes. Timothy Osborn, a miner, discovered that a night out in Stockton, California, in the early 1850s included the opportunity to pay 2 cents to a Frenchman offering “a vue de Paris.” The view turned out to be “naked men and women in the very act.” Osborn noted in his diary that he had seen “a very good view of Paris.”5

Comstock had been attempting to sanctify his life by strenuously following God’s laws. He believed that what one read or viewed had an immediate effect on one’s soul. (How, precisely, he managed to spend his career looking at and reading the very materials he considered too dangerous to be in the public’s hands was not something he addressed in public statements or writing.) “Good reading,” he explained, “refines, elevates, ennobles, and stimulates the ambition to lofty purposes.” Parents, teachers, and pastors needed to wake up to the pervasive threat of “Evil Reading,” which controlled young people’s minds and perverted their desires.6

His experiences as a soldier in the Union Army inspired him to launch a personal war against filth. Erotica was ubiquitous among his fellow soldiers, yet no one else seemed sufficiently concerned about the immoral items that soldiers and officers shared. After the war, Comstock settled in New York City, the center of American commercial erotica production and sale. From his rented room on Pearl Street in Lower Manhattan, he inventoried the brothels, saloons, dance houses, and gambling dens that operated nearby. Many booksellers and printers had successfully paid off police officers to protect their goods from seizure in the past, but rampant corruption was no match for Comstock’s persistent intrusions.7

Business titans on the board of the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) admired Comstock’s moxie. They paid him $100 a month, and individual donations added up to a salary of about $3,000 per year (approximately $75,000 in 2024). It was enough to allow him to fight vice full-time.8

After passage of the Comstock Act in 1873, the postmaster general appointed Comstock to be the Special Agent of the United States Post Office Department, responsible for overseeing the act’s enforcement. When the Post Office hired only four additional inspectors, Comstock looked to other agencies for help. In his home state of New York, the legislature deputized members of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice (NYSSV), an offshoot of the YMCA, to confiscate “obscene” materials.9

Comstock kept meticulous records of his arrests and raids. He proudly noted that he and his agents had destroyed more than 202,000 “pictures and photographs” by the end of 1876. During the same period, they seized 21,000 pounds of books. Comstock instigated the arrests of well-regarded photographers who printed erotic images or exhibited them through stereoscopes. New state-level anti-obscenity regulations were even more severe; “little Comstock laws” in thirty states banned or criminalized the sale, distribution, and possession of sexual materials. More than three-quarters of the arrests by 1900 were for violations of these state laws.10

Comstock and his agents did not wait for citizen complaints to root out obscenity. They sent decoy letters requesting sexually explicit materials and used false names to solicit contraceptive or abortion-related services, arguing in court (with imperfect success) that their deceptive methods nevertheless supported a conviction. They went undercover in brothels and other “vice resorts,” sipping wine and playing poker until a formal solicitation justified an arrest. It was Comstock’s belief that without the “vice” trades, the market for contraception would dry up.11

Comstock famously disguised his identity to implicate a well-known abortion provider, midwife, and contraception purveyor who went by the name of Madame Restell and whose real name was Ann Trow Summers Lohman (1811–1878). Restell was a veteran criminal defendant by the time Comstock set his sights on her in the 1870s. She had been charged with a misdemeanor in 1847 for the death of a fetus after performing an abortion on a woman whose pregnancy was not yet “quick.” Restell was found guilty and spent a year in the bleak prison on Blackwell’s Island, which was also the site of an almshouse and the New York Lunatic Asylum. Upon release, she almost immediately resumed her lucrative mail-order business, selling contraceptives and abortifacients, and reopened her lying-in hospital, where she delivered babies. She had a net worth in the millions and lived in a mansion on East Fifty-Second Street in Manhattan. All could agree that Restell was ubiquitous. Her advertisements appeared—with almost no innuendo—in newspapers and magazines. She rode through New York City in a lavish carriage, wearing “silks, satins, velvets, furs, and diamonds,” generating controversy based on both her occupation and her refusal to apologize for it.12

Critics sneered that Restell’s wealth derived from the outrageous price of silence. Perhaps wealthy clients were desperate enough to keep their own or their family’s contraceptive emergencies out of the public eye that they paid Restell exorbitant fees. In the 1840s, the National Police Gazette and other local papers stepped up their criticism of Restell and her customers. These publications celebrated male sexual license but denigrated any woman who acquiesced to “an invasion of the course of nature.”13

Restell provided abortion care amid a national movement to ban it. In 1857, the recently established American Medical Association (AMA) started a decades-long campaign to outlaw abortion at every stage of pregnancy. That effort reflected the moralism of some of the AMA’s leaders as well as the organization’s broader aim of replacing midwives with physicians in the care of pregnant and laboring patients. Prominent physicians such as Horatio Storer contravened centuries of common wisdom (and common law), which had marked quickening as the beginning of fetal life. Storer, instead, defined abortion at any stage of pregnancy as murder. The AMA demanded that only male doctors should diagnose a pregnancy—and never intervene to end one. Between 1880 and 1930, abortion was criminalized throughout all the individual states, often with exceptions only to save the life of the pregnant person.14

In the late 1870s, Comstock arrived at Restell’s home and, without giving a name, claimed to be in search of medicine to help a woman end a pregnancy. Restell sold him two medications (a tonic and a pill) that, if taken according to her instructions, would likely cause a miscarriage. Comstock returned about a week later, still not identifying himself, and professed to now be in search of a “preventative” for his female friend. This time, Restell sold him a powder, instructing him to mix it into a contraceptive douche that the woman could inject deep within her vagina immediately after sexual intercourse. Local police accompanied the man when he returned for a third visit four days later, carrying a warrant to search her home. Only then did Restell recognize the man as Comstock. The officers walked out with armloads of contraceptive powders, condoms, syringes, written instructions, and pills.15

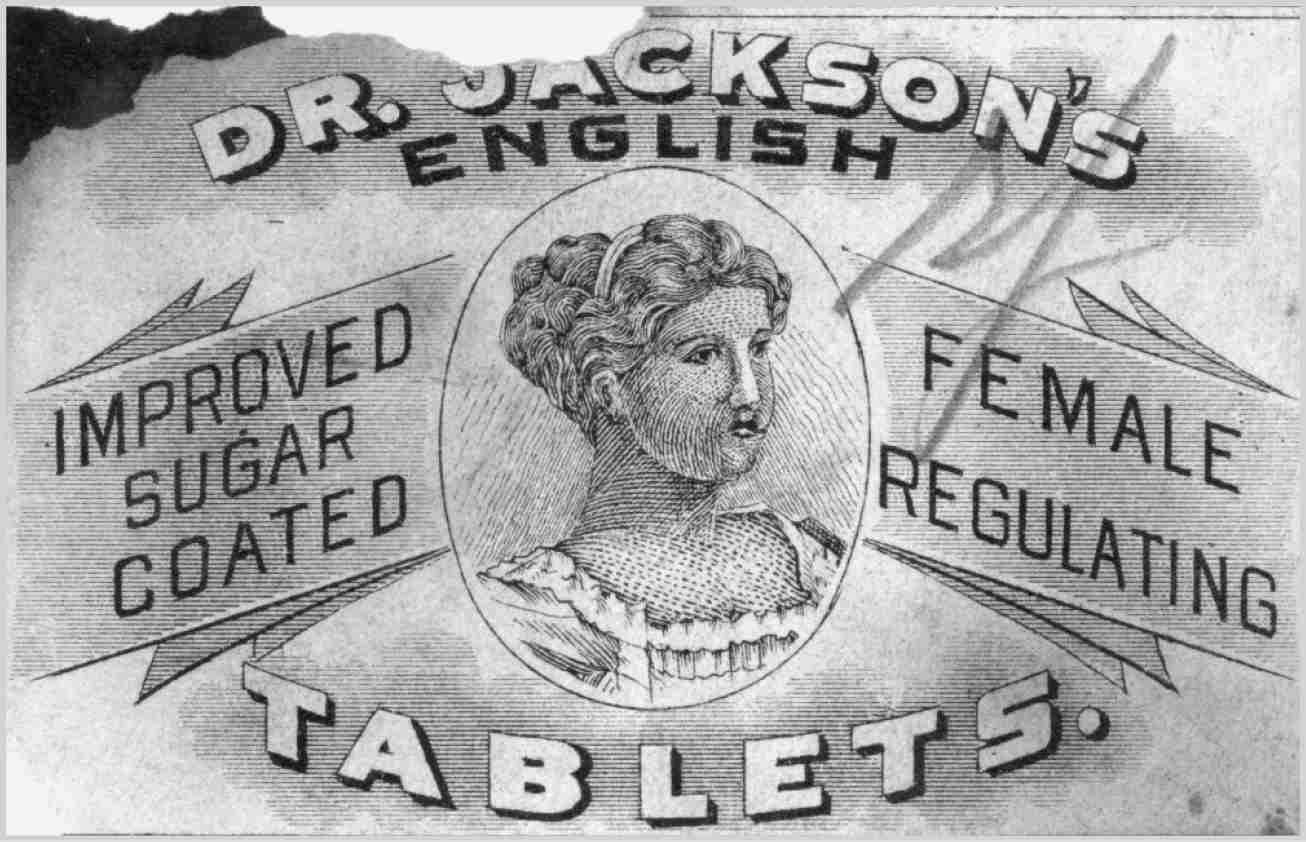

Purveyors of contraceptives and abortifacients, like Madame Restell (a pseudonym for Ann Trow Lohman), who operated out of New York City, advertised products like this box of “female regulating tablets” in newspapers and magazines. Dr. Jackson’s Improved Sugar Coated English Tablets, 1880–1900, lithograph trade card, Bella C. Landauer Collection of Business and Advertising Ephemera, 96539d, New-York Historical Society.

After her arrest, Restell was held for several weeks in the Tombs, a detention center in Manhattan, until her lawyer pressured the police judge to accept an exorbitant $10,000 bail. A grand jury indicted Restell for selling and advertising items “for the prevention of conception,” she was arraigned, and a trial date was set. Restell knew what awaited her on Blackwell’s Island if she was found guilty. Rather than face another conviction, she undressed and climbed into her bathtub, where she slit her own throat. Restell was one of the first people, but not the last, who chose death over Comstock’s persistent harassment.16

The scope of what Comstock considered “obscene” kept expanding, exceeding all reasonable limits. He and his agents seized postcards sold on the Bowery showing photographs of naked women, dime-store novels with steamy innuendo, and copies of Leo Tolstoy’s Kreutzer Sonata (1889), which discussed prostitution. They targeted art schools in Philadelphia that employed living models and declared war on art high and low that featured nude female bodies. Comstock confiscated and destroyed tens of thousands of books, sexually explicit photographs and photograph negatives, sheet music, “rubber goods,” advertising circulars, playing cards, stereotype plates, account books, and private letters, not to mention trick cigar cases that hid photographs of naked women and liquor bottles shaped like a penis and testicles.17

Only a small fraction of the cases Comstock brought were against providers of contraception and abortion services, and even fewer of those prosecutions ended in conviction. But he chose his targets strategically, arresting women with prominent businesses and attempting to silence them. Sarah Chase, a successful contraceptive entrepreneur and homeopathic physician, was arrested five times between 1878 and 1900 for distributing printed information about sex and contraceptive devices, such as a syringe that she said was intended as a hygienic aid, not a means of inducing abortion. Juries acquitted Chase all but once, when she received a ten-year sentence, for an abortion she performed that ended in the woman’s death. Comstock brought most of his cases against individuals who printed, sold, or displayed anything that he considered obscene, but jurors and judges were skeptical of his methods and even less inclined to prosecute men and women for private sexual behaviors.18

The law was more effective in encouraging euphemism and omission. Dr. Edward Bliss Foote removed a discussion of condoms and womb veils from his marital guide after his 1874 conviction and fine. And Chase was unable to continue publication of her health journal, The Physiologist and Family Physician, after it was briefly banned from the U.S. mail in 1881.19

Raids on druggists and local proprietors frustrated people’s efforts to access contraceptives, but clearly Americans found other ways. By 1900, the national fertility rate of white American women was 3.54 births, half of what it had been one hundred years prior. The decline was especially pronounced among urban, native-born, middle-class women whose husbands were employed in the professions or business. One study in 1910 found that two-thirds of U.S. families did not have more than two children.20

Yet white women were prominent among the hundreds of thousands of volunteers who joined Comstock as “purity crusaders.” These activists wanted to bring down the double standard—not by liberating women to enjoy the opportunities for sexual self-expression available to men, but by raising men to middle-class white women’s assumed level of sexual decorum. Both prostitution and obscenity stood in the way of those goals. Purity crusaders likewise agreed with Comstock about the corrupting effects of “impure” images and words. While most of these activists were native-born white women, the middle-class members of African American women’s clubs similarly resolved to discourage the presence of any “obscene literature” or uncouth songs in Black homes.21

Legions of Protestant women affiliated with the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) argued that voluntary efforts—purity pledges, industry codes, and library committees—might rid the nation of sexual “filth” as effectively as any government action. Founded in 1872, the WCTU originally focused exclusively on ending the sale and consumption of alcohol. Under the leadership of Frances Willard, from 1879 to 1898 the WCTU grew into a formidable national organization with semi-independent state chapters. The WCTU also ventured into other causes that reflected a Protestant vision of moral purity. Willard and like-minded activists believed that external forces pushed some women into prostitution rather than it being entirely a matter of sin. They held men to account by promoting a “White Life for Two,” which encouraged men to sign pledges to remain virgins until marriage and abstain from visiting sex workers.22

Unlike Comstock, the women of the WCTU did not simply destroy “obscene” literature but created “pure” alternatives. They established “purity libraries” purged of such salacious content as Jane Eyre and periodicals with advertisements that featured sexualized images of women. Their own magazine, The Young Crusader, aimed instead to provide wholesome content to impressionable younger readers. Over time, the WCTU’s leadership came to see the women who participated in salacious cultural productions as victims of patriarchal degradation rather than purveyors of smut. They remained opposed to any public display of female nudity.23

Purity crusaders fought an uphill battle. No matter how many “rubber goods” Comstock and his agents confiscated, sex entrepreneurs found new outlets on a black market of unregulated, obliquely described contraceptives and sex toys. Proprietors small and large renamed condoms “capotes” and variously called pessaries “uterine elevators,” ladies’ shields, protectors, womb supporters, and “married women’s friends.” Some euphemisms pre-dated the Comstock Act, but by the 1870s, advertisements for contraceptives obscured the products’ original purposes. Retailers mentioned only the vague benefits of “protection” and safety, noting that their goods provided “reliability” for married women. Even Comstock’s name became a term for contraceptives; stores and circulars advertised postcoital douches as “Comstock syringes.”24

The Egyptian women’s performance at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition seemed almost designed to provoke Comstock. In late July, he exited the Cairo Street theater full of righteous outrage. One member of his entourage pronounced that they had “been to the mouth of hell to-day.” Comstock’s subsequent decision to reenact the dance for a reporter, his rotund form hardly capturing the pelvic muscle flexions that belly dancing involved, provoked mirth rather than sympathetic outrage.25

Despite Comstock’s protests, the fair’s organizers refused to shut down the danse du ventre. Comstock had three “heathen” dancers arrested and fined when they came to New York City later that year to perform their “obscene & indecent exhibition.” There was little else he could do, as the dance became a national sensation.26

If Comstock’s anger was to be expected, few could have foreseen the rousing defense of the dance by an obscure, brilliant, and unconventional thinker named Ida Craddock. She was a free-love mystic and independent scholar who spent years as a “student of Phallic antiquities.” Craddock presented her research on phallic symbols in ancient religions to liberals and freethinkers in her hometown of Philadelphia who dared give her the podium; her topic was an audacious one for a female speaker. Hoping to continue her studies at the University of Pennsylvania, in 1882 she passed the grueling, four-day entrance examinations. Members of the university’s board of trustees debated whether to admit her as their first female student, ultimately deciding against it. Seemingly undeterred, she drafted a book-length manuscript on the history of sex worship in which she argued that earlier cultures had worshiped male and female sexuality. In these initial years of academic anthropology, “primitive” religions were typically understood as inferior to Christianity or “Anglo-Saxon” cultures. Craddock instead found inspiration in ancient rituals that seemed to honor—rather than shame—women for their erotic power.27

Ida Craddock (1857–1902) was a freethinker who applied to the University of Pennsylvania’s graduate program in anthropology to study “phallic antiquities.” Denied admission because she was a woman, Craddock instead patched together a living as an educator and marriage counselor. Committed to free speech and sexual candor, she was enthralled by the danse du ventre at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. She was hounded by Anthony Comstock to the point of suicide.

Craddock eked out a living teaching stenography at Girard College in Philadelphia, and as a secretary for the American Secular Union, an organization fiercely opposed to the very sort of evangelical Christianity that drove Comstock’s crusade against sexual speech. Unlike some of the freethinkers she associated with, Craddock did not oppose religion per se but rather wanted to untether spirituality from rigid doctrines. She also agreed with other women’s rights activists of the time that organized religion too often provided the rationale for women’s oppression. Liberal and reform-minded, Craddock celebrated the somatic pleasures of a liberated spirit.28

A small but vocal free-speech movement shared many of Craddock’s goals. The married couple Angela Fiducia Tilton Heywood and Ezra Hervey Heywood became notorious in the 1870s and 1880s for their radical demands for sexual frankness. Angela, in particular, pushed the limits of sexual speech. In an 1889 issue of The Word, the newspaper Ezra edited, Angela wrote, “As a girl, I used to say, in myself, ‘When I grow up I shall deal with men’s penises, write books about them; I mean to and I will do it.’ ” She especially wanted to expand women’s vocabulary about their bodies. There was a profusion of vernacular expressions for the word “penis,” she explained, but women had hardly any for the vulva. This linguistic inequality, she argued, disadvantaged women when they engaged in sexual conversation with men.29

When The Word advertised “the Comstock syringe for Preventing Conception” in 1882, Comstock had Ezra arrested. A sympathetic judge guided the jury to a not-guilty verdict, but Ezra was arrested again in 1890, when he was sixty-one years old. This time, he was found guilty of obscenity for publishing a letter in which a mother described how she had explained the meaning of “fuck” to her twelve-year-old daughter. For that offense, Ezra spent two years performing hard labor at Charlestown State Prison while Angela raised their four children on her own. Ezra died within one year of his release.30

Craddock found support among free lovers, but her advice about sexual pleasure was radical even by their standards. She based her philosophy on what she described as her ecstatic communions with a spiritual husband, a fantasy or dreamlike figure with whom she experienced, she wrote, deeply fulfilling sex. “My husband is in the world beyond the grave,” she explained, “and had been for many years previous to our union, which took place in October, 1892.”31

Plenty of post–Civil War Americans believed in the possibility for communion with the dead. Seances and spirit mediums grew only more popular in the wake of the war’s enormous toll. While many Americans comfortably combined spiritualism with Christianity, Craddock drew upon her research in “eastern” religions for her theology of spiritual eroticism. Some of these religions, she thought, offered esoteric guidance on how to attain spiritual liberation through the correct practice of male-female sexual intercourse. Although never technically married, Craddock presented herself as an expert on marital intimacy, including the wedding night, based on her encounters with her spiritual husband.32

The danse du ventre in the Egyptian Theater thrilled Craddock. In the pages of the New York World, she praised the dancers for enacting “the apotheosis of female passion” and self-control, their pelvic movements mirroring the undulations of a woman’s body in the throes of sexual ecstasy. The dance, she explained, “trains the muscles of the woman in the endurance desirable in the wife.” Speaking directly to the possibilities for women’s erotic pleasure, Craddock described this sexually liberated woman as an ideal sexual partner for a man, prepared “not only for receiving, but also for conferring pleasure.”33

Where Craddock witnessed spiritual communion, Comstock saw the road to hell. That road, Comstock and his supporters believed, followed a steady descent from civilized “Anglo-Saxon” Christians to the depravity of darker-skinned “heathen” people. Some scandalized onlookers compared the performance on Cairo Street to Native American dances and pagan rites. Associating non-Christian cultures with sexual immorality was part of a larger effort in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to argue for the superiority of white or “Anglo-Saxon” people. For Comstock and many others, Christianity alone promoted sexual morality.34

Craddock became one of Comstock’s prime targets in the decade after the fair. She went to prison in 1898 for mailing pamphlets that provided explicit instructions to husbands about how to satisfy their wives. Comstock had Craddock arrested again in August 1899 for mailing another one of her pamphlets. This time, the lawyer Clarence Darrow, a well-known defender of free speech, paid her bail bond of $500 and took on the case pro bono. Darrow brokered a plea deal that gave Craddock a three-month suspended sentence, but only after she agreed to incinerate all the pamphlets she wrote.35

Then, in February of 1902, Comstock and three of his deputies raided Craddock’s tiny apartment on West Twenty-Third Street in Manhattan. They arrested her for selling her new sexual guide, The Wedding Night, to an undercover detective. A jury returned a guilty verdict after a brief deliberation.36

What was it that Craddock wrote that so offended Anthony Comstock? She sold pamphlets and offered marriage counseling to teach men and women “an Oriental method of ideal coition,” intended to ensure the woman’s sexual gratification while “rejuvenating the entire being of both husband and wife.” The man would learn how to achieve “prolonged coition, from at least a half hour to an hour after entrance.” She presented this advice in The Wedding Night and Right Marital Living, which she mailed to people who signed up for her $10 correspondence course. Her students completed a lengthy self-assessment. In her questionnaire for men, after inquiring into the person’s sources of sexual information and physical health, Craddock asked about the frequency of sexual intercourse with a wife or mistress, its duration “(three minutes, ten minutes, a half hour, one hour, or what?),” and the details of orgasmic experience. “Have you ever gone right through the orgasm (the final thrill), without spending semen, and with a certain heightened enjoyment of the orgiastic thrill which is impossible if the semen be expended in the usual way?” Such frank questions about sexual behavior, along with queries about erections, masturbation, and foreplay, put Craddock decades ahead of her time.37

Craddock’s attentiveness to sexual consent was also extraordinary. She asked male students, “Are you accustomed to demand, or even to respectfully request the privilege of coition without previous lovemaking?” Yet her blunt questionnaires revealed a contradiction in the ways that she and nearly all free lovers and radicals celebrated sexual knowledge. Even as she insisted on a woman’s consent and mutual pleasure during heterosexual intercourse, she offered unsparing denigration of same-sex sexuality. As Craddock queried on her questionnaire, “Do you practise homo-sexuality (that is, unnatural vice with your own sex)?”38

In October 1902, the night before she was to be sentenced on federal charges, Craddock closed her apartment windows, sealed off the crevices beneath the door, and turned on the gas. She was forty-five years old. Her mother and a police officer found her body the next morning, along with a letter in which she explained that she could not endure another prison sentence. She dreamed, she wrote, of a world free from “Anthony Comstocks and corrupt judges.”39

In the 1910s, radicals took to the streets to challenge legal restrictions on sexual speech and contraception. Emma Goldman, a Russian-born anarchist, explained in 1911 that “Sex is the source of life [and] where sex is missing[,] everything is missing.” She viewed sexual freedom, including equal access to safe contraceptives, as critical to class struggle, a way for working-class women to control the number of mouths they had to feed.40

Margaret Sanger, a nurse, free lover, and, at the time, socialist, made the expansion of contraceptive access her life’s work. Sanger and other countercultural “Bohemians” of the era argued that the constraints of heterosexual monogamy were politically, spiritually, and sexually toxic. “Sexual modernity” emerged in socialist periodicals such as the Masses, in street-corner speeches, in literature and art, and in the cacophonous conversation of cafés and bars. Making the world anew required not only the toppling of industrial captains but also the dismantling of the conventions of monogamy and patriarchy. Sex need not have anything to do with procreation, and marriage need not require monogamy. In line with many of the sexual moderns inhabiting Greenwich Village apartments, working in Provincetown theater companies, writing for socialist magazines, and experimenting with art and romance, Sanger considered women’s sexual autonomy—and thus reliable contraception—to be the foundation of their liberation.41

Margaret Sanger (1879–1966), a nurse who found a community among Greenwich Village’s free-love “Bohemians,” became the face of the American birth-control movement after she was arrested for distributing her pamphlet “Family Limitation.” She opened the country’s first birthcontrol clinic in Brooklyn, one year before this photo was taken.

That vision directly challenged Comstock’s limitations on sexual speech. In 1914, Comstock told journalist Gertrude Marvin that “there is a personal Devil sitting in a real Hell tempting young and innocent children to look at obscene pictures and books.” Published in the Masses, Marvin’s interview with Comstock set the latter up for derision. His ideas seemed increasingly out of touch. That same year, Sanger’s magazine, The Woman Rebel, popularized a new term, “birth control,” and challenged restrictions on information-sharing. Later that year, Sanger was arrested for printing “Family Limitation,” a pamphlet offering the type of detailed contraceptive information she had thus far omitted from The Woman Rebel. She briefly fled the country (and spent her time learning about contraceptive clinics in northern Europe).42

Sanger audaciously defied anti-obscenity laws by opening a birth-control clinic in 1916 in Brownsville, a working-class Brooklyn neighborhood of mostly first- and second-generation Jewish and Italian families. For nine days, Sanger and her sister Ethel Byrne met with hundreds of women who waited for an appointment in queues that stretched around the block. When one of these patients turned out to be an undercover police officer, Sanger and her colleagues were arrested.43

Sanger lost her case on appeal in January 1918 but won a small victory when the appellate judge carved out an exception for contraceptive devices intended to prevent disease (in other words, condoms), if prescribed by a physician. Druggists ignored the fine print, and corner pharmacies and other shops soon offered a growing assortment of condoms for sale, no longer shrouded in euphemism. Sanger made the most of the publicity that the trial generated. She fundraised, opened a research bureau, and founded the American Birth Control League. By the late 1920s, local birth-control groups operated clinics throughout the Northeast and Midwest United States.44

Mary Ware Dennett, who also lived among Greenwich Village freethinkers and activists, relentlessly fought federal and state Comstock laws, although hers was not a hedonistic celebration of sexual energies. “Sex relations belong to love, and love is never a business,” Dennett concluded. In her pamphlet, The Sex Side of Life (1919), she wrote about sexual pleasure as a source of personal joy. “The physical side of love is the intensely intimate part of it, and the most critical for happiness . . . so it is the one side of us that we must be absolutely sure to keep in good order and perfect health, if we are going to make any one else happy or be happy ourselves.” In the 1910s, while Sanger advocated for birth control as a necessity for women’s freedom and workers’ rights, Dennett spoke not only of pleasure but of health and survival.45

Dennett drew from her own experiences of terror and pain to become a fierce advocate for women’s right to comprehensive information about sexuality and reproduction. She gave birth to three children near the turn of the twentieth century, one of whom died of starvation at three weeks old because she was too ill from his delivery to breastfeed him. After the birth of a third child, Dennett’s doctor warned her to avoid another pregnancy at all costs, which in the absence of reliable contraception meant the cessation of sexual intimacy with her husband, Hartley. He responded that his “individual sovereignty” required that he have the freedom to have sex with other women. In particular, he wanted to spend more time with Margaret Chase, a married woman who was socially and financially prominent within the radical literary circles the Dennetts traveled in. Many of the Greenwich Village Bohemians had affairs with married and unmarried partners as part of their exploration of sexual pleasure disentangled from middle-class moralism. Mary’s expectations of marriage were incompatible with Hartley’s, and she obtained a divorce in 1913.46

Dennett wrote The Sex Side of Life because she knew that far too many women faced each pregnancy fearing death in childbirth and uncertain of what, if anything, they could do to protect their own health. The pamphlet contained basic information about male and female reproductive anatomy. With an emphasis on the naturalness of sex and its essential connections to romantic love, Dennett discussed ovulation, menstruation, sexual arousal, masturbation, and venereal diseases. Almost immediately, the postmaster general banned the pamphlet from the U.S. mail on the grounds that it violated anti-obscenity laws. Dennett was undeterred and filled 25,000 more orders. In 1928, she was indicted on federal charges after a postal inspector entrapped her by soliciting a copy under a false name. In a signal victory, New York’s Second Circuit Court of Appeals in 1930 determined that her sex-education pamphlet did not constitute obscenity. The pamphlet’s “decent language,” the judge ruled, was precisely what young people needed lest they “grope about in mystery and morbid curiosity” for knowledge about sex.47

Comstock died in 1915, but his crusade against obscenity persisted. The Progressive Era of the early twentieth century was characterized by confidence in the ability of experts to solve social ills such as poverty and unwed pregnancy. Comstock had to drag police officers along with him to arrest purveyors of pornographic texts in the 1870s, but by the early twentieth century police departments embraced the idea that they should surveil sexual commerce. Anti-vice commissions in forty-three cities investigated the prevalence of prostitution and the conduct of young women at dance halls and gambling dens. Agents went undercover to “vice resorts” and tabulated the nature and quantity of the sexual services they offered. Plainclothes policewomen served as decoy patients in attempts to ensnare abortion providers and midwives.48

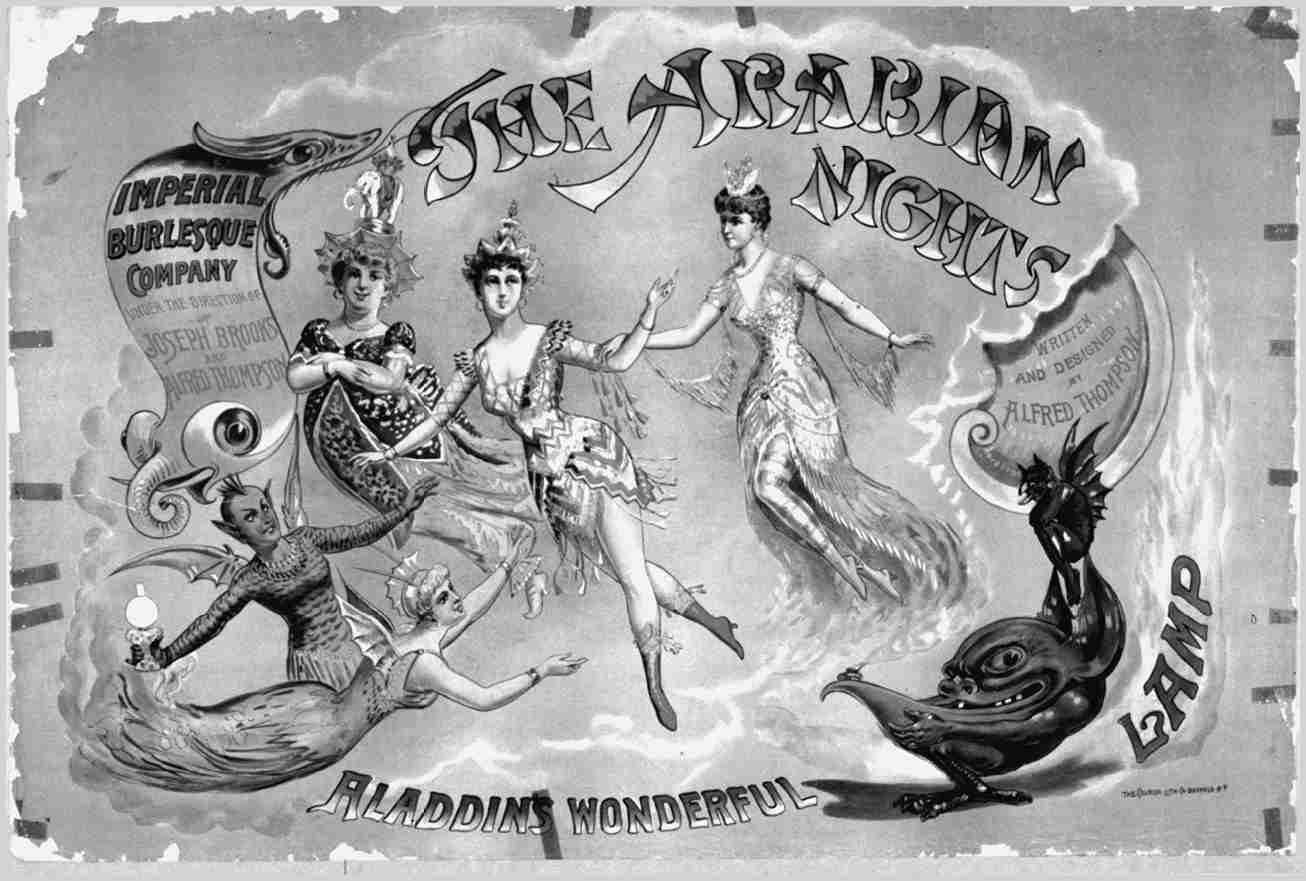

The common association in the United States between Middle Eastern cultures and “exotic” sexuality inspired burlesque theater managers to add “Arabian” dance routines to their shows. In this poster from an 1888 production of the Imperial Burlesque Company, a sinister representation of Aladdin’s lamp likely implied a titillating performance featuring a young woman threatened by insidious sexual dangers.

Definitions of obscenity continued to shift. Burlesque theater managers who already parlayed popular fantasies about exotic “foreign” women with acts that staged retellings of 1001 Arabian Nights now adapted the “hootchy-kootchy dance” and its fantasy of “foreign” sensuality for their stages. Dancers at the 1893 World’s Fair had worn folk dresses, but women doing the danse du ventre on burlesque stages wore translucent, loose-fitting costumes and shed scarves as they gyrated. In St. Louis, a performer named Omeena performed “the couchee-couchee or houchie-chouchie, or tootsie-wootsie . . . in the presence of men only,” her act concluding when she was nearly naked. Many burlesque entertainers wore flesh-toned bras and underpants, and the illusion of nudity they gave, aided by stage lighting and body makeup, was key to their popularity.49

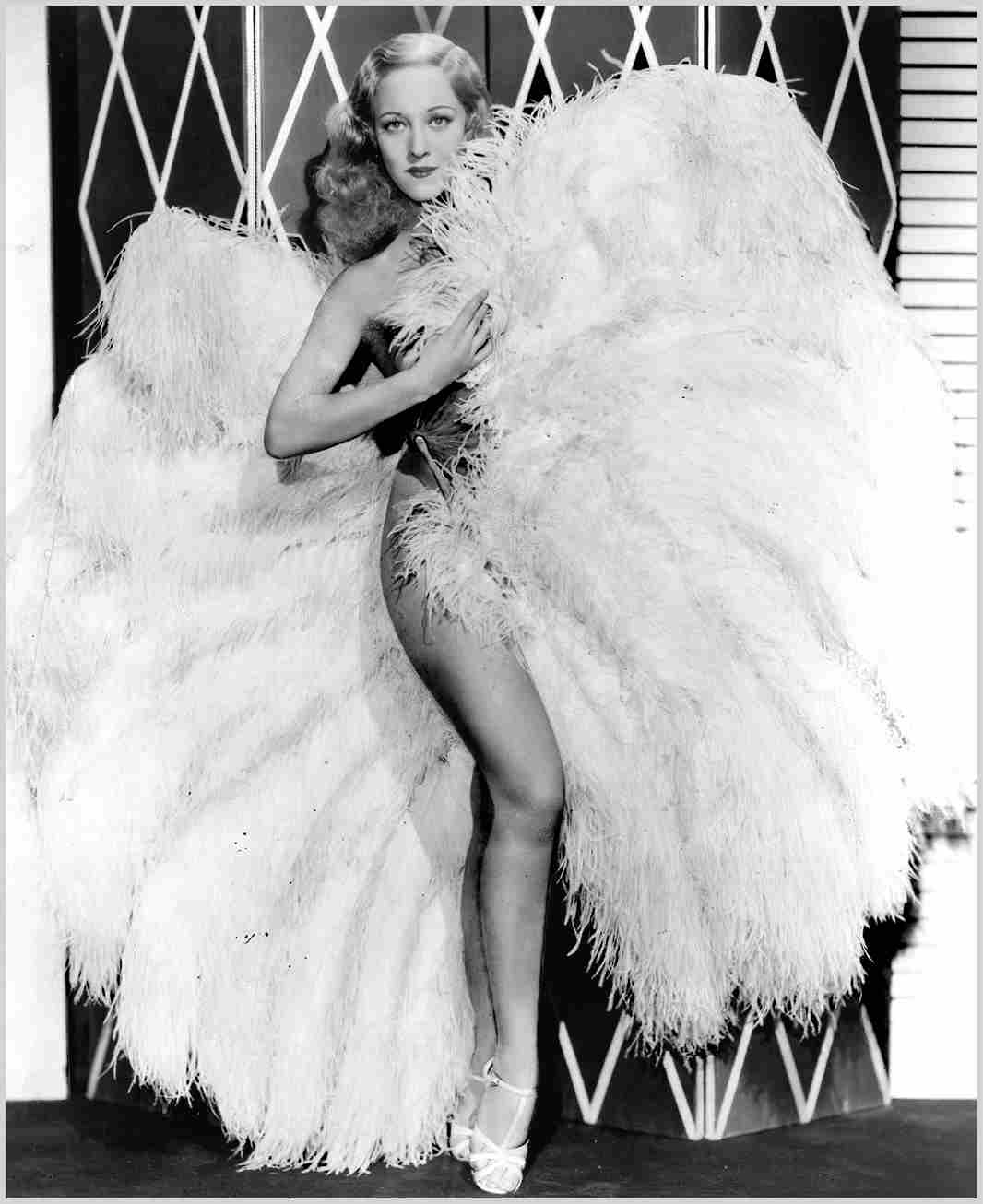

Fifty years after the danse du ventre at the Egyptian Theater horrified Anthony Comstock, Sally Rand’s “fan dance” drew crowds at the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago. This photo of Rand from 1934 shows how she used the fans, tricks of lighting, and a body stocking to give the audience the impression that she was naked onstage.

Fahreda Mahzar, one of the women who captivated audiences with the danse du ventre at the 1893 fair, performed it once again at the 1933 Century of Progress International Exhibition in Chicago, wearing the same long skirts she had worn forty years earlier. But this time, the mere suggestion of exotic sexuality failed to stir the audience’s imaginations. Mahzar, after all, did not take off her clothes.50

Instead, a dancer named Sally Rand drew the crowds at the 1933 fair. Taking the stage in a floor-length, translucent gown and high-heeled shoes, Rand carried two enormous, ostrich-feather fans. She twirled elegantly to a romantic instrumental tune, spinning herself until she was backlit behind a screen, her fans raised overhead to reveal the silhouette of her naked form. Assistants removed her gown so that when Rand spun herself out from behind the screen, she seemingly had only the fans to cover her—one held to the front of her body, one in back. Facing the audience, she raised up one fan, then swiftly lowered it while raising the other. Her routine coyly concealed her breasts, buttocks, and genitals, offering the audience tantalizing but inconclusive glimpses.51

Rand was technically never fully nude when she performed her fan dance (body stockings and pasties covered key parts of her anatomy), but she was arrested on obscenity charges several times. Throughout the United States, police carried on Anthony Comstock’s mission to rid the public square of sexually exciting material. But in Rand’s moves, and in the thrill of audience members, Ida Craddock’s insistence on naming and expressing erotic pleasure claimed its place.