Chapter 10

Plays Too Stirring for a Boy Your Age

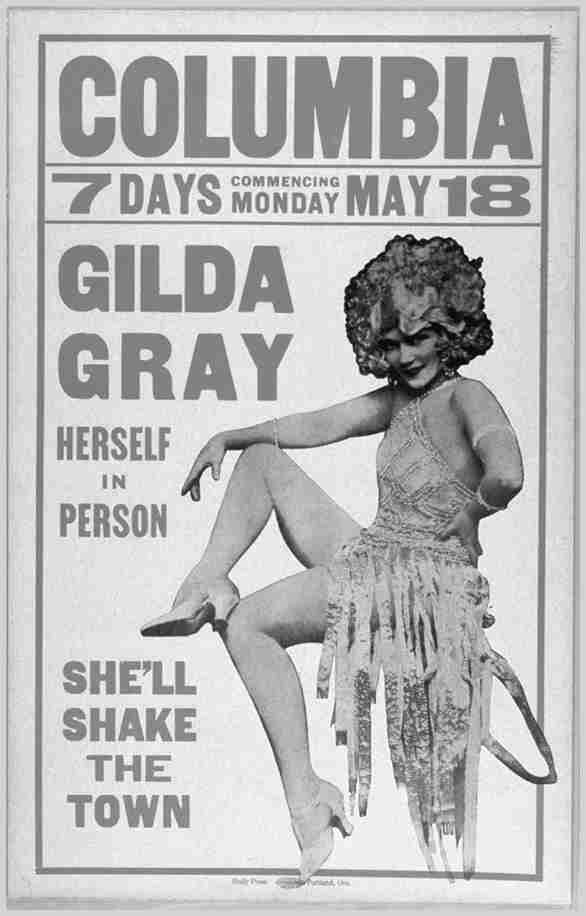

Moral-purity reformers worried that burlesque shows contributed to a culture of sexual permissiveness, especially among America’s youth. This poster, printed in Oregon and likely from the 1930s, teased customers with the promise of a risqué event. From the perspective of many young people, though, seeking sexual pleasure by watching a burlesque show or reading a raunchy magazine was essential to the human experience.

Howard Gan found himself in court in October of 1909 because he wanted to paint the town red. Howard was a young white man in his late teens living at home with his stepmother, Emma, his father, and three siblings. Emma expected Howard to contribute wages he earned as a clerk to the household budget, and they argued over how much he owed her. Howard thought $1 a week should suffice. Perhaps he reasoned that this would leave him with plenty of money for an evening out, when he would enjoy performances by comedians, jugglers, and chorus girls at one of the no-frills burlesque theaters in Cleveland, Ohio. A clerk’s wages might not cover rent, but they afforded boys like Howard enough cash for a meal and a show, an opportunity to step out of his stepmother’s household and imagine a life beyond it. Like the hundreds of thousands of other young people living and working in American cities in the early twentieth century, Howard recognized that cash could purchase access to sensual pleasure.

When Emma demanded that Howard give her $3 from his weekly wages, he balked. Maybe they shouted. Perhaps she threatened him. She was only eleven years older than him (and just six years older than Howard’s sister Frances), and she may have struggled to gain his respect as an authority figure in the household. What is clear is that with a balled-up fist or the palm of his hand, Howard assaulted her. Neighbors may have heard the ruckus; someone brought a police officer to the scene. So it came to be that Howard stood before Police Judge Manuel Levine in a downtown Cleveland courthouse to answer for his crime.1

Judge Levine was committed to the progressive movement, which stressed the shaping force of social and economic circumstances on behavior and emphasized rehabilitation over punishment. In Howard Gan, the child of a German immigrant father, Levine saw a youth who would either mature into a stable adult or grow so enamored of base sexual pleasures that he would embark on a career of vice. “You will go home with your mother,” Judge Levine ordered, stepping easily into his role as a surrogate father, “and behave yourself better.”2

Judge Levine’s authority within the courtroom represented but one small piece of the government’s rapidly expanding authority over sexual behavior. These new developments included local policing mandates to round up “vagrants” and “sexual delinquents,” expansive anti-prostitution measures that targeted immigrants and interstate travelers, and campaigns to raise the “age of consent” and enforce laws against statutory rape.3

At the time of his arrest, Howard was what psychologists had recently termed an “adolescent,” a developmental stage halfway between childhood and adulthood that was considered pivotal to one’s eventual progression to emotional and sexual maturity. Social reformers had already started to portray these years as fraught with confusion and danger. Judge Levine agreed that teens needed guidance. The sexual pitfalls he saw in Howard’s path were all too apparent. “You must keep away from the burlesque houses,” Levine concluded. “The plays are too stirring for a boy of your age—and keep out of saloons.”4

All the elements of this otherwise obscure episode from a police court in Cleveland point to how differently Americans approached sex among younger people by the turn of the twentieth century. Few disagreed about the need to do something to address an apparent crisis of youthful sexual vulnerability. From the 1880s through the 1920s, reformers and legislators undertook new measures to protect children, and girls in particular, from the abuses they associated with commercialized sex. In doing so, they debated questions about the age at which a child became capable of giving consent, the culpability of teenage boys in these encounters, and whether the role of the state was to punish or reform “wayward” youth.

The notion that childhood extended past the age of ten, and that teens did not yet possess the maturity or resourcefulness of adults, gained traction in the nineteenth century. In the 1850s, some women’s rights reformers began to warn against marriages between older men and “baby wives” who had not reached legal adulthood. Numerical age became a steadily more significant measure of a person’s maturity—and, in tandem, of their sexual allure. By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, popular culture portrayed young women as especially attractive, while new statutes and policing practices cast girls as sexually vulnerable. This combination of youthful allure and vulnerability drew the attention of psychologists and reformers.5

Among the most influential theorists of youthful sexual urges was G. Stanley Hall, a psychologist who also served as president of Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts. In his two-volume work, Adolescence (1904), Hall defined adolescence as a chaste interregnum between childhood and marriage. Much as Sylvester Graham and Sarah Mapps Douglass had in the first half of the nineteenth century, Hall characterized the young person’s sexual awakening as a critical moment. But although Hall had been raised to see sexual desires and masturbation as religiously and physically dangerous, he wanted young people to understand that sexual pleasure was natural. At the same time, he warned that the capacity for sexual restraint was what distinguished “civilized” from “savage” races. These theories resonated with Freud’s ideas about sexual degeneracy, though Hall emphasized biological inheritance rather than subconscious impulses.6

Hall shared with many leading American social scientists of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries an unabashed confidence in the evolutionary superiority of “Anglo-Saxon” people. British scientist Charles Darwin’s theories of human evolution and “natural selection” changed the way Americans understood the origins of racial differences. Talk about “the race” suffused social movements and national politics: in 1904, President Theodore Roosevelt warned of “race suicide” if Japanese men could immigrate in greater numbers to the United States; he feared that Japan’s supposedly less-civilized-but-still-manly men would take jobs from—and emasculate—American men. Although Darwin offered theories of evolution’s biological effects, American and British social scientists saw these ideas about racial inheritance as a road map for social engineering.7

The popularity of Darwin’s theories of survival of the fittest inspired what became known as the eugenics movement. Scientists, physicians, policymakers, and others believed they could improve the “fitness” of the American population by controlling who could reproduce with whom. State-wide eugenics programs sterilized vulnerable individuals whom physicians, prison wardens, mental health workers, or judges deemed hereditarily “unfit” (whether disabled or simply poor). Indiana passed the first eugenic sterilization law in 1907. All told, tens of thousands of men and women, most of them white residents of psychiatric hospitals or prisons, were surgically sterilized by the 1960s. Authorities had concluded that these people possessed physical or mental traits too detrimental to risk inheritance by the next generation. At the federal level, immigration laws passed in the 1910s and 1920s severely restricted arrivals from eastern and southern Europe, Asia, and other regions whose residents struck the all-white and mostly Protestant members of Congress as inferior to northern European “stock.” A third effort, shorthanded as “pronatalism,” developed premarital education and marital counseling programs to encourage native-born, educated, white citizens to marry at younger ages and produce larger families, thereby preserving “superior” white people’s numerical dominance. By the early twentieth century, the eugenic idea that humans could “breed a better race” was mainstream.8

Hall’s insight was a theory called “recapitulation,” which described each individual’s development as human evolution in miniature: a progression from the primitive impulses of childhood to the mature self-control of adulthood was akin to the progress of human societies. He argued that adults in “primitive” (non-white) cultures remained stuck in an earlier evolutionary stage and thus lacked the inhibitions that northern European cultures had achieved. Eastern and southern Europeans, who predominated among the new immigrants (and whom many white Americans did not consider fully white), lacked Anglo-Saxon maturity, as did the hundreds of thousands of African Americans migrating north to escape Jim Crow. Adolescence, then, served in this analogy as the critical stage at which a person learned to channel their impulsive drives into productive work and monogamous marriage, necessary milestones along the path to evolutionary improvement.9

What, then, of adolescent boys like Howard, who clearly lacked the maturity of adulthood but whose wages gave them access to a new world of cheap amusements? Young people pursued pleasure well beyond the mostly male or family-oriented pastimes of the nineteenth century. In the growing cities of the early twentieth-century United States, mixed-gender peer groups visited amusement parks and dance halls. A few cents bought time at one of the peep shows cropping up on the margins of urban entertainment zones, sometimes viewed through a single-viewer kinetoscope. Nineteenth-century women who caroused in saloons and who walked without a chaperone in cities were often presumed to be sex workers; by the early twentieth century, working- and middle-class girls and women could safely enjoy urban entertainments without being associated with sexual commerce. Streetcars and, soon, automobiles moved courtship away from family parlors and front porches to dimly lit backseats far from parents’ control.10

A new practice known as “treating” meant that the wages that Howard and boys like him earned were essential to their access to the company of girls of their social class. A teenage boy or young man might, for instance, pay for a teenage girl’s dinner and tickets to an amusement park with the expectation that she would, in turn, provide companionship and possibly some degree of erotic play. A precursor to modern dating culture, “treating” offered women and girls a way to access public amusements—and to engage in premarital sexual acts ranging from kissing to intercourse—without damaging their reputations.11

Reformers emphasized that it was girls and young women whose virtue was imperiled by this new blend of youth, money, and sex, but that was not always the case. An investigation in Chicago in the 1920s found that some newsboys engaged in sex with older men in exchange for money that they then used to “treat” girls in their peer group. Sex work was prevalent in same-sex encounters between boys and men in the early twentieth century (a subject that the next chapter explores), but at least in the case of the Chicago newsboys, those exchanges helped male adolescents participate in a heterosexual peer culture that depended on access to cash.12

Racy vaudeville routines and movies contributed to a culture of sexual candor. Vaudeville was the most popular entertainment form in the United States at the time, with approximately 400 dedicated theaters throughout the United States and as many as 5,000 smaller venues in 1906. Vaudeville troupes promised wholesome entertainment for the whole family, but some of the jokes were suggestive enough that reformers found them offensive. The nascent film industry gradually started with short films projected by the vitascope in the late 1890s. The invention of the nickelodeon in 1907 soon challenged vaudeville’s dominance. Representations of female desire played across those screens. One of Thomas Edison’s most famous early films, What Demoralized the Barbershop, centered on the flustered responses of male barbers and their customers at the sight of the stocking-covered legs of girls visible through the window of a street-level door. The film conveyed an increasingly common message. Physicians had begun to encourage girls and young women to exercise, and while bicycle riding was controversial, girls and young women learned that they should invest more time in the improvement of their bodies, the display of which would draw men’s attention.13

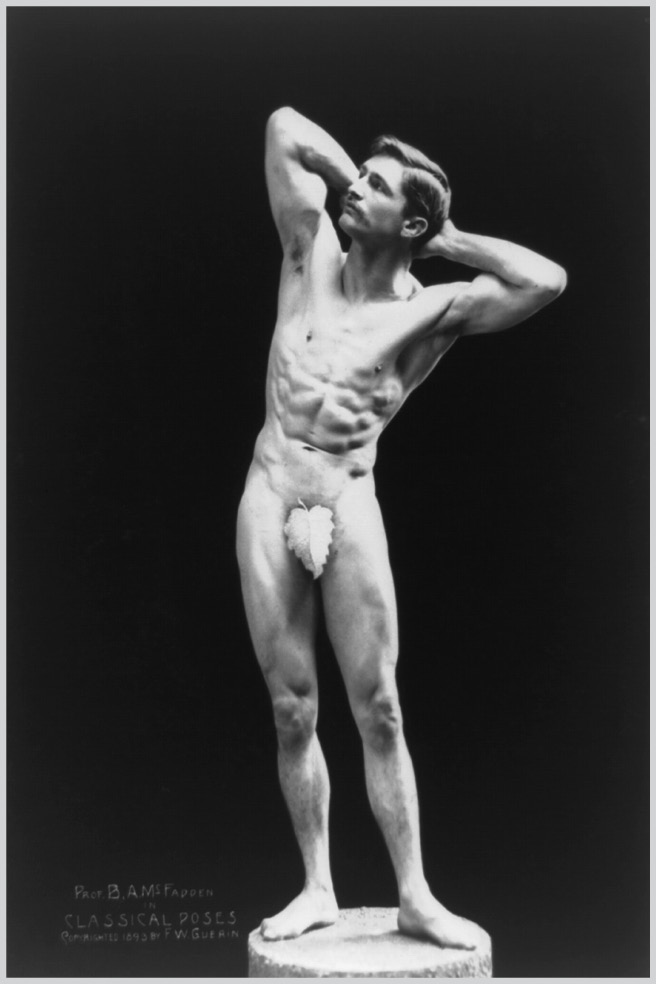

Bernarr McFadden (1868–1955) promoted bodybuilding and admiration for the male physique through his books and magazines in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, often standing nearly nude in imitation of the muscular builds of men in Greek statues. This image, in which he is “posed as the modern Hercules,” is one of dozens of similar photographs of him showing off his physique in his 1895 book,McFadden’s System of Physical Training.

Advertisers soon recognized the market potential of young people with cash and a desire to attract one another in a social world of their own making. Boys like Howard learned that they needed to become capable lovers with something called “sex appeal.” Perhaps Howard read one of the new physique magazines published by Bernarr McFadden, a bodybuilder who had himself photographed nude, muscles flexed. Howard might have spent some of his wages on cologne. These combined pressures produced a novel American interest in heterosexuality: not simply in the existence of male-female pairings but in the idea that men’s and women’s desire for one another was necessary, normal, and important.14

New popular spectacles encouraged boys like Howard to gaze at respectable young women’s bodies to an unprecedented extent. The Miss America competition debuted in 1921 with a revue of “bathing beauties” along the Atlantic City boardwalk, wearing suits that revealed far more flesh than previous fashions had allowed. Tourism boosters for Miami, Florida, portrayed their city as an oasis where “Miami Mermaids” (always depicted as white in the city’s promotional materials) lounged on its beaches in one-piece bathing suits. Burlesque theaters introduced the strip tease and made their shows more sexually explicit, such as a Minneapolis act in which the women were “entirely nude with the exception of three ribbon rosettes,” two of which, “about the size of a fifty-cent piece . . . were worn one on each breast,” with a third rosette “worn over the pelvic region.” The dancers paraded down a runway to cries of “Shake ’em up girls! Shake all you got for the boys!”15

Hall’s fascination with adolescence as a crucial developmental stage, particularly for boys, avoided a question that women reformers had taken to heart: how could they protect girls from the sexual dangers that these youthful freedoms presented?

In the 1880s, across the United States, most state laws defined the legal age of consent for sex as either ten or twelve years old, norms established centuries earlier under English common law; in Delaware, the age of consent was seven. These laws defined sex with a female under that age as criminal conduct, regardless of the child’s verbal consent or physical resistance. For social-purity reformers who saw girls and young women as sexually vulnerable, such standards no longer sufficed. Under New York State law, they warned, a girl “is held by [the state’s] criminal laws to be legally capable of giving ‘consent’ to her own corruption at the tender age of TEN YEARS!” Activists hoped to convince legislators to raise the age of consent and demanded enforcement of statutory rape laws. Because the laws applied to girls of ten as much as to teens of seventeen, prosecutions included cases of child rape as well as instances of consensual sexual experimentation among young people nearly old enough to marry.16

The energetic reformers in the WCTU added the reform of age of consent laws to their agenda for Christian morality in the late 1880s. At a time when public speech about adult women’s sexuality remained taboo, this campaign allowed women to decry a double standard that too often blamed girls who had been abused of being unchaste. Their efforts were, by several measures, hugely successful: by 1920, the lowest age of consent in the United States stood at fourteen in Florida. Legislators in every other state had raised it to sixteen or eighteen. Revised criminal codes distinguished between rape (widely understood as forcible sexual intercourse during which the victim resisted and fought back with all of their strength) and statutory rape, in which the consent of the minor was immaterial to the perpetrator’s guilt. Prosecutors brought charges against men who sexually assaulted children under the new laws. Because judges and juries often excused a certain degree of male aggression as a normal part of heterosexual relations, age-of-consent laws offered girls who did not consent to sex a new means of putting their assailants on trial. Successful prosecutions nevertheless often depended on presentations of girls and young women as helpless victims, with little understanding of sex.17

Sometimes it was parents who called the police for help when their attempts to turn their daughters away from older boyfriends failed, to force the father of a pregnant daughter’s child to agree to marriage, or in the hope that the police could teach their daughters to respect authority. Virginia Zuniga contacted authorities in northern New Mexico in 1912 after her twelve-year-old daughter, Refugia Zuniga Torres, left home with Ricardo Alva, a twenty-five-year-old who boarded in their home. After police discovered Torres and Alva walking to a town where they said they planned to get married, Alva was arrested and charged with rape. (Since 1897, the age of consent in New Mexico had been fourteen.) Zuniga protested that she had no intention of charging Alva with a crime but rather wanted the police to bring her daughter home. Mexican parents expected young men to ask for permission to date their daughters, but their American daughters instead took advantage of what one Mexican mother described as the “terrible freedom” of American girls.18

Zuniga’s concern was echoed in the comments of Black parents in New York City who invoked that state’s delinquency statutes to discipline their daughters. Reformers tended to view Black, working-class, and immigrant families as the sources of girls’ delinquency. Judges sentenced convicted Black girls to prison or to live hundreds of miles away with relatives in the South, where they would supposedly escape the moral turpitude of their urban environments and learn “traditional” values. Many parents nevertheless pleaded with prison staff to lessen their daughters’ sentences or permit early parole, often because they needed the girls to contribute wages or labor to their households.19

The WCTU’s emphasis on the innocence of vulnerable girls contrasted with new laws that treated girls as instigators of sexual crimes. In the 1880s, New York passed the first in a series of “wayward minor” and “incorrigibility” statutes that permitted the arrest and detention of girls who had not committed any crimes. Rather, a young person need only be considered “in danger of becoming morally depraved” to face arrest. (New York’s wayward minors law targeted only girls until modifications in 1925 broadened its scope to include boys.)20

Courts often sent convicted wayward minors to private reform programs or, if pregnant, to privately run “maternity homes.” By the 1920s, prisons such as New York’s Bedford Hills Reformatory for Women increasingly handled these cases, housing sexually curious but inexperienced youth alongside the sex workers and petty criminals who comprised much of the prison population. Sexual behavior became the defining category for girls’ criminality: in 1920 in the Los Angeles juvenile courts, 81 percent of the girls (under the age of eighteen) who were arrested were brought in for “morals” offenses, compared to only 5 percent of the boys. Boys were almost never charged with delinquency for consensual sex with girls.21

Black reformers concerned about the sexual morality of their youth had to contend with sexual stereotypes that presumed Black people’s lasciviousness. In 1889, the white historian Philip Bruce argued that because Black people were innately promiscuous, they reverted to a pre-slavery state of licentiousness when Emancipation loosed them from the civilizing constraints of white paternalism. In that natural state, Bruce explained, Black women were perpetually sexually willing, and Black men, unaccustomed to any woman refusing their advances, became violent rapists. Bruce placed much of the blame on the failures of Black mothers to teach their daughters sexual modesty. Such viciously racist ideas were pervasive not only throughout much of the South but in the halls of academe.22

Black women such as Ida B. Wells and other advocates for “racial uplift” believed that sexual decorum, or “respectability,” was both a moral imperative and a strategy for racial advancement. Wells made this argument despite some more conservative Black leaders’ criticism: one prominent minister chastised Wells for speaking publicly about matters related to sexuality. Single women such as her, he warned, would better advance their race if they married and bore male children.23

She was undeterred, and she had good company. After the Civil War, Black women formed religious auxiliary clubs and local social-improvement societies devoted to “uplifting” other Black Americans through education, Christianity, and civic engagement. These Black women insisted that they were sexually respectable—and likewise insisted that other Black men, women, and young people demonstrate comparably virtuous behavior. Black clubwomen established sex-education programs and maternity homes for unmarried, pregnant girls. They created courses on social hygiene and marriage education at historically Black colleges and universities and urged the expansion of public health programs to reduce Black maternal and infant mortality rates, both of which far exceeded rates for whites (as they still do in 2024). Yet they also cultivated what one scholar termed a “culture of dissemblance”: they presented themselves as beacons of bourgeois virtue, often at the expense of acknowledging their own sexual agency.24

“Respectable” behavior was also believed to be essential for the promotion of the next generation of healthy Black babies, amid a 50 percent decline in Black birth rates between 1880 and 1940. A Black educator named Ariel Serena Bowen spoke to the Negro Young People’s Christian and Educational Congress in Atlanta in 1902 about the risks of “passions running riot,” especially when they led to “child marriage.” Bowen shared the popular belief that girls who became sexually active and pregnant at too young an age bore sickly children. Other reformers produced pamphlets that warned against promiscuity and “self-abuse,” urging young African Americans to see sex not as simply an expression of physical passions but as a crucial decision with implications for the entire race. Acutely aware of the ways in which slavery and ongoing racial violence exposed Black girls and women to constant fears of sexual assault, Wells and Bowen emphasized individual morality and communal rectitude to guide their young people to a better future.25

The plight of Chinese sex workers living on the West Coast aroused a national panic over the existence of a new form of slavery, one that was fueled by immigration, and that exploited vulnerable girls and young women. Most people of Chinese origin then residing in the United States were male, having arrived after 1848 to labor for railroad companies with the intention of returning to their wives and children in China with the wages they earned. White Americans suspected all women arriving from China and Japan of being sex workers, and it is likely but impossible to verify how often this was the case. Chinese and Japanese women became sex workers in the United States because they had been sold by impoverished parents to procurers; had entered what they thought were licit marriages, only to have their supposed husbands sell them to brothels; or were kidnapped. They lived and worked under appalling conditions, suffering a high degree of violence and continual sex work.26

Reformers debated whether to rescue or expel foreign-born sex workers. The Page Act of 1875 specifically banned Chinese women who intended to work as prostitutes from entering the country. If a woman from China could not prove that she was the legal spouse of a man already residing in the United States, she was sent back.27

Yet the Page Act exacerbated the conditions it set out to resolve by ensuring the continuation of a “bachelor culture” among Chinese people in the United States. Their imbalanced gender ratio became, in turn, a further justification for the denigration of Chinese people’s sexual morality. (In California, Chinese men outnumbered Chinese women 22 to 1 in 1890, and as late as 1920, there remained a 5 to 1 imbalance.) White Americans spread unsubstantiated rumors that Chinese bachelors lured white women and girls to their “opium dens” or laundries. A riot erupted in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in 1889 after two “Chinese demons” were accused of “ruining” innocent white girls, ages eight to thirteen. (In fact, one of the thirteen-year-old girls may have been a street-gang leader who, in addition to experiencing abuse, acted as a procurer.) The very presence of Chinese men in the United States was portrayed as a threat to white women. Anti-Chinese press coverage and political cartoons contrasted scenes of exhausted Chinese laborers living in all-male, slovenly, and potentially queer spaces to scenes of orderly, heterosexual white families, where a male worker returned home to a wife and children.28

Reformers began to call the plight of coerced sex workers “white slavery”: an international network that sent children and young women from eastern and southern Europe to the United States to work as prostitutes. (Some reformers included women from China in their description of white slavery’s victims, but most did not.) They warned that single female immigrants might be intercepted as soon as they disembarked on U.S. shores by a deceitful procurer who promised respectable employment but corrupted the young woman into sexual servitude. Fundraisers supported Traveler’s Aid and other groups that met single women at seaports and railway stations, directing them to “clean” forms of employment. Reformers presumed that immigrant women and girls who had moved to cities from the rural hinterlands and ended up selling sex did so against their wills.29

This illustration by Thomas Nast, which appeared in Puck magazine in 1878, contrasts the gender arrangements (and, implicitly, the morality) of Chinese and “American” workers. In the left-side image, a group of Chinese “bachelors” occupy a squalid, cramped dormitory in an opium den, where they subsist on rats. On the right, a healthy-looking white man returns home to a tidy domestic scene, with a dutiful wife and children. Images like these proliferated in anti-Chinese campaigns, and they often depicted Chinese people as socially and sexually chaotic.

Yet few of the girls or women who earned a living as sex workers met the definition of white slaves. The cruelty that forced Chinese and Japanese women on the West Coast into brothels was unusual; most women engaged in prostitution in the 1910s chose to do so as a temporary means of survival. Katharine Bement Davis, the first superintendent at Bedford Hills, from 1901 to 1914, found that it was the children of immigrant women who turned to sex work in disproportionate numbers, learning from their native-born peers. Along with African Americans, immigrant women and their daughters faced poverty and social dislocation, not trafficking.30

By the 1910s, a new immigration policy allowed for the deportation of foreign-born sex workers. It was not always clear that a woman facing deportation for prostitution had been forced into sex work. Immigration officials and reformers tended to presume that white women had been coerced and that Asian, Black, or Mexican women willingly sought it out. Further defining prostitution as un-American, a clause in the 1917 Immigration Act stipulated that any woman convicted of prostitution was ineligible for naturalization, even if she married a U.S. citizen. And contrary to a stated concern with European girls who became white slaves, immigration officials deported women of Mexican origin at much higher rates than any other nationality between 1910 and 1920.31

The signature legislation designed to combat white slavery was the 1910 Mann Act, which prohibited the transport of female minors (younger than eighteen years old) across state lines for prostitution, “debauchery,” or “any other immoral purpose.” The law defined as a felony even the intent to bring a woman into the country or take a woman across state lines for “illicit purposes.” The Bureau of Investigation (the precursor to the FBI) created a White Slavery Division and obtained approximately 2,300 convictions for trafficking between 1910 and 1918. Under the Mann Act, women were charged with conspiracy for arranging their own transportation to visit their boyfriends in other states. There was no similar constraint for men, whose solo travel was not subject to prosecution.32

The arrest of the African American boxer Jack Johnson became a notorious example of the law’s selective enforcement. Johnson was a world champion, a powerfully built athlete famous for his dramatic victories in the ring against white men. He was also unapologetic about his relationships with white women. In 1913 police officers dredged up evidence that Johnson had traveled across state lines in 1909 with Bell Schreiber, a sex worker with whom he had an affair. Johnson was found guilty and sentenced to a year in prison, despite the lack of any evidence that he had traveled across state lines to pay for sex or to force Schreiber to engage in sex for money. Those details appeared to be beside the point: he was a Black man who asserted his right to sexual pleasure with white women, and white law enforcement authorities wanted to punish him for his audacity. By the 1920s, the law targeted cases of adultery or interracial sex more often than cases of prostitution.33

How to handle adolescent girls who quite clearly chose to have sex outside of marriage was another matter. Raymond Fosdick, an attorney and reformer, testified before a congressional committee in September 1917 “that venereal disease was coming not from the prostitutes but from the type known in the military camps as the flapper—that is, the young girls who were not prostitutes, but who probably would be to-morrow, and who were diseased and promiscuous.” Fosdick worked for the American Social Hygiene Association, funded by John D. Rockefeller Jr., which approached sexual vice in the United States less as a problem of “white slavery” than as a public health crisis.34

As U.S. soldiers began to assemble at military bases in preparation for the nation’s entry into the Great War, government and military leaders discovered that an astonishingly high number of enlisted men—126 out of every 1,000—were infected with venereal disease. Infection rates among Black soldiers were even higher than the overall average. So prevalent was gonorrhea across the United States in the early twentieth century that some scientists speculated that all women might carry the germ in their genitourinary tract, where it stayed latent until it infected a male partner.35

The social-hygiene movement aimed to eradicate venereal diseases by eliminating prostitution but also by restricting the freedoms of girls and women. Far from the vulnerable girl in age-of-consent or white-slavery campaigns, sexually enthusiastic female adolescents now took the blame for endangering their male peers. Fosdick supported the formation of a wartime Committee for Protective Work for Girls, which sent out 150 women to patrol the streets surrounding military encampments, searching for wayward youth.36

Social hygienists working for the military produced a sixteen-page pamphlet, Keeping Fit to Fight, which was also made into a short film. These materials were remarkable at the time for their frankness about sexual function, commercialized sex, and disease. Fit to Fight portrays the adventures of five soldiers who go out for an evening of drinking and are propositioned by sex workers. Only one of the five demurs. Among those who assent, one man gets gonorrhea and two get some form of syphilis. Only one man who had sex with a prostitute escapes infection, because he uses a post-exposure prophylactic, a treatment that the army and navy had reluctantly begun to make available to servicemen. The abstinent man, teased for his rectitude, retorts that he is “not a coward because he won’t go with a dirty slut.” The American soldier, like the young man listening to a lecture by Sylvester Graham in the 1830s, heard messages about the need to practice self-restraint. Unlike Graham’s lectures, the military’s materials denigrated American women for their sexual immorality.37

Public displays of heterosexual pleasure were growing more common, however; Howard Gan and his contemporaries wore down the resistance of their stepmothers and the courts as the world of commercially available sex-related entertainments expanded. Here was sexual modernity, a celebration of the individual pursuit of pleasure amid experts’ warnings about rebellious adolescents. The interplay of expressiveness, family concern, and state-sponsored attempts at control shaped Gan’s life for at least a moment in 1909; it would prove dramatically more consequential for the lives of queer and gender-nonconforming people who experienced modern sexuality as a celebration of pleasure tempered by new fears of state repression.