Chapter 14

Public Masturbator Number One

Betty Dodson (1929–2020) moved to New York City to become an artist. Following a six-year marriage, she immersed herself in the city’s sex scene, enjoying group sex, pornography, and erotic painting. In 1968 she had a successful gallery show in Manhattan that featured life-size drawings of couples having sex.

“We celebrated Groundhog Day with a small sex party.”

In the annals of the history of sexuality, there is perhaps but one enthusiast who would think to commemorate the minor holiday in those terms. But Betty Dodson was no ordinary chronicler of sexual behaviors and information. Describing herself as “America’s Public Masturbator Number One,” Dodson devoted her adult life to experiencing, teaching about, and advocating for the pleasures of solo and partnered orgasm.1

Dodson’s career spanned decades and cultural eras. In the late 1960s, she resolved to liberate women to enjoy masturbation. Her advice was a radical departure from even previously boundary-pushing works. Sex and the Single Girl, the 1962 bestseller by Cosmopolitan editor Helen Gurley Brown, encouraged single women to see sex with men as a pleasure they were entitled to enjoy, and also, when strategically arranged, a means to career advancement. Dodson wanted women to view solo sex as the foundation of their sexual, spiritual, and political emancipation, not as a means to an end. She stripped sex of its contexts, idealizing instead an erotic experience unaffected by race, class, gender, or other identities. Hers was, in many ways, an especially privileged white, middle-class argument for sex’s singular importance to human liberation. As a call for women to name, own, and celebrate their orgasmic capacity, it was also more than a bit revolutionary.2

At lectures and at the all-female, completely nude workshops she hosted in her apartment living room, Dodson taught women to appreciate and admire their genitals, to prioritize the erotic importance of the clitoris, and to embrace the satisfactions of a good vibrator. Always more than a bit outside the mainstream, even as the mainstream shifted, she was an adult-film devotee during the “golden age of porn” in the 1970s, promoted women’s sex-toy companies, enjoyed group sex and kink, and became embroiled in the “sex wars” among anti-porn and pro-sex feminists in the 1980s. Not long before her death at the age of ninety-one in 2020, Dodson shared her lifetime of orgasmic knowledge with actor and entrepreneur Gwyneth Paltrow for a Goop Lab (Netflix) episode about women’s sexuality, perhaps hoping to reach the affluent but erotically underinformed female audience that Paltrow attracted to her “lifestyle” company.3

The arc of Dodson’s wild career illuminates the radicalism as well as the limitations of sex-positive feminism. She glossed over the class dimensions of sex equality and was oblivious to its racial complexities. In denouncing erotic inhibition, she minimized the risks of assault and the effects of abuse. Reducing women’s liberation to orgasmic independence oversimplified the reasons for gendered power differences and women’s subordination.

What endeared Dodson to multiple generations of women—and what has remained controversial—was her adamant refusal to shroud women’s erotic pleasures in shame. In the late 1960s and 1970s, Dodson envisioned an erotic insurgency on the horizon, in which women would claim pleasure for themselves. What seemed self-explanatory to her instead drove a wedge into the women’s liberation movement and provided an easy target for defenders of sexual conservatism.

A 1960 Cosmopolitan magazine article answered the question posed by its title, “Do Women Provoke Sex Attack?” with a resounding “yes.” Women should scrupulously monitor their own behavior, lest they arouse a man “past the point of no return” after which, “when the girl resists, he seeks gratification by force.” Staying “chaste” until marriage was, the dominant narrative insisted, a young woman’s responsibility.4

Dodson rejected that advice wholesale. She grew up in Wichita, Kansas, where her mother, Bess, ignored the repressive politics of Wichita’s evangelical Christian culture. In 1934, when a five-year-old Betty masturbated in the backseat of the family car during a long road trip, Bess did not interrupt her because “that was such a long trip and we were so short of money and you kids weren’t having that much fun.” Bess’s nonchalance about her daughter’s autoeroticism was extremely unusual. Although health experts in the 1930s had largely jettisoned more than a century of warnings about masturbation as a disease, the idea that solitary sex was both physically injurious and psychologically damaging persisted.5

Betty likewise refused to view premarital sex as a precursor to a life of pain and degradation. “First intercourse (sexual) at 20 yrs old[.] It was good,” she noted matter-of-factly in the margins of a personal narrative she drafted years later as she was launching her sex workshops.6

Television shows and film later portrayed the 1950s as the wholesome era of June Cleaver and suburban tranquility, but young women in the United States did not universally conform to that image. Like the “Victory Girls” who unabashedly pursued sex with U.S. servicemen during World War II, Dodson owned her sexual desires. Her sexual adventures exposed her to far less risk than unmarried white women had faced even a decade earlier. Victory Girls were periodically rounded up as threats to the morals and health of U.S. servicemen, but Dodson benefitted from being at the leading edge of white women’s heterosexual liberation. Civil libertarians and sex educators advocated toleration of nonmarital heterosexual sex, to distinguish private and therefore protected acts from truly criminal behaviors, such as prostitution and rape. (As Chapter 16 explores, this shift coincided with stepped-up policing of Black women’s sexuality.)7

Dodson arrived in New York City in 1950 after one year of college and several years’ experience creating art and advertising copy for a local newspaper and department stores. She was already unusual for not marrying directly out of high school. Dodson wanted to live the life of the successful, sexually uninhibited artist. She spent five years studying classical drawing and painting, paying her way with a combination of scholarships and freelance fashion-illustration gigs. Although her art and self-presentation initially remained somewhat conventional (she wore dresses and kept her hair long), Dodson had a series of boyfriends and casual sex partners with whom she explored her enthusiasms. She pursued the sort of libidinal freedom that a new magazine, Playboy, promised urbane American men from its first issue in 1953. With partially naked women posed for its centerfolds, celebrity interviews, and advice about hi-fi stereos and sophisticated cocktails, Playboy presented a fantasy world of sensual gratification. Publisher Hugh Hefner envisioned a sexual playground for straight men, but Dodson saw no reason why she couldn’t have as much fun as the boys were having.8

Contraception made it possible for Dodson to enjoy sex without fear of pregnancy. Before she left Wichita for New York, the spermicidal jelly she used during sex failed her and led her to seek what turned out to be an unanesthetized illegal abortion “on a dingy kitchen table.” After that harrowing experience, Dodson borrowed a friend’s engagement ring to convince a gynecologist to prescribe her a diaphragm. That woman-directed method of birth control, which Margaret Sanger had touted since she opened her first clinic in Brooklyn in 1916, was typically available only to married women—or engaged women who could convince a sympathetic physician that they were almost married. Legal impediments remained even after the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) authorized the first oral contraceptive for women in 1960. Enovid, manufactured by the G. D. Searle company, was nearly 100 percent effective; by 1962, 1.2 million American women were taking it daily. Women like Dodson who were already sexually active were the ones most likely to ask their physicians for a prescription (contrary to complaints that “the Pill” inspired young women to rush out and initiate premarital sex). Dodson stayed loyal to her diaphragm for the duration of her fertile years. Given that early iterations of the Pill had such high doses of hormones that many women experienced blood clots and other painful side effects, Dodson was wise to avoid it.9

A 1965 Supreme Court case, Griswold v. Connecticut, protected the right of married people to access contraception as a matter of privacy, if not of women’s sexual liberation. The Griswold decision occurred amid a wave of efforts throughout the United States to decriminalize private sexual acts involving consenting adults. Unmarried women’s access to physician-prescribed contraception was not protected until 1972, in Eisenstadt v. Baird.10

Still, fear of becoming an “old maid” spurred Dodson to get married, in 1959, when she was twenty-nine years old. Her husband, an advertising executive, was a kind person but an unsatisfying lover, and they soon ceased to have much of a sex life together. Masturbating in secret was her only way to experience the pleasures that popular culture had led her to think she would find in the marriage bed. Dodson and her spouse never managed to reconcile their divergent erotic needs.11

An amicable divorce after about six years of marriage left Dodson in possession of a rent-controlled apartment, some financial security, and a burning desire to find more compatible sexual partners. She “cut loose.” “I want to be a pervert,” she told her friends—a daring if privileged aspiration at a time when the idea of queer people’s “psychopathic personality” continued to shape immigration policies, civil rights law, and policing. “I want to be one of those sex fiends.” Her erotic encounters proliferated and grew more satisfying. Petite and fit, Dodson cut her hair shorter, started a regular yoga practice, and launched into her new life’s work.12

Her companion in many of these adventures was a former professor named Grant Taylor, a longtime (if never exclusive) partner who was as willing as Dodson was to experiment. They dove headfirst into the group-sex scene. By the late 1960s, the growing popularity of “spouse swapping” and group sex had attracted the attention of academic researchers and prompted occasional (and, naturally, sensationalistic) press coverage. Unlike most “swappers,” Dodson and Taylor were unmarried, but they fit the profile of the white, middle-class individual who predominated in the American swinging subculture and in films such as Bob and Carol and Ted and Alice (1969), which was nominated for four Academy Awards. Dodson expanded her relationship with Taylor into a committed group that included his new girlfriend, Sheila Shea, and another couple.13

She also mounted gallery exhibits of her drawings of nudes, some featuring pairs having sex, some of individuals masturbating. Negative reactions to her life-size masturbation drawings convinced her that the world was more sexually repressed than she had realized: “I called every woman I knew and asked if she was masturbating. If she wasn’t, I suggested she start immediately.” She even called her mother, who was sixty-eight and a widow. (After initial reticence, Bess reported two weeks later to her daughter that she was having solo orgasms.)14

Dodson belonged to a new wave of sex educators who argued that autonomous sexual pleasure was normal and even essential. They argued that, far from being physically or mentally damaging, masturbation improved a person’s bodily and emotional health, much as Kinsey had noted in his 1953 study of female sexuality. But Dodson’s celebration of masturbation for its own sake was unusual. Even the sex researchers William Masters and Virginia Johnson, authors of the famed study Human Sexual Response (1966), extolled masturbation principally as a way to improve marital sex, a view echoed in much of the sex therapy of the 1960s and 1970s. The pursuit of sexual pleasure for oneself became Dodson’s obsessive goal. She pieced together a living by “creating erotic wallpaper,” “running commercial sex parties,” and more.15

Dodson’s desire to tell the world about the power of masturbation and orgasm quickly ran afoul of anti-obscenity laws, a thorn still deep in the side of free-speech advocates, sex educators, and pornographers nearly a hundred years after Anthony Comstock went to Washington to plead his case before Congress. The offending item was “The Fine Art of Lovemaking,” a long-form interview with Dodson published in the February 1971 issue of the Evergreen Review, a highbrow literary magazine. Amply illustrated with sixteen of Dodson’s sex drawings, the interview gave the “woman painter of erotic art” an international platform to present her theories. She proudly described herself as both a feminist and a pornographer.16

The definition of legal obscenity was far from clear. Roth v. United States (1957) defined obscenity as whatever “the average person, applying contemporary community standards,” would consider to be something that principally “appeals to prurient interest.” Although the Roth test created a First Amendment protection for anything understood to express “even the slightest redeeming social importance,” it offered censors a basis for restricting sexually explicit films, magazines, and books as violations of “community standards.” Homophile magazines like ONE, which contained no nudity, were thus especially vulnerable to prosecution. Both American culture and U.S. law had grown significantly more tolerant of explicit sexual material, but law enforcement continued to single out “perverse” forms of sexual expression, particularly anything relating to homosexuality, for harsher restrictions.17

Defining obscenity—and determining how, if at all, to limit it—confounded the Supreme Court, which issued a series of contradictory decisions between the mid-1960s and the early 1970s. Memoirs v. Massachusetts (1966) held that John Cleland’s infamous novel was not obscene and strengthened First Amendment protections for sexually explicit work. Just a few years later, however, the Supreme Court reversed course in Miller v. California (1973) and made it easier for material to be found obscene, so long as the “average person, applying contemporary community standards,” would conclude that the material lacked “serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.” Paris Adult Theatre v. Slaton (1973), handed down the same day, likewise permitted governments to ban obscene materials for the sake of maintaining “a decent society.” Dramatic shifts in those “community standards” made successful obscenity prosecutions increasingly rare, but the possibility for government censorship endured. Dodson’s aim was to set sex free from all limitations.18

The “obscene” art that Dodson showed in galleries paled in comparison to the “hard-core” pornography on screens in an increasing number of American movie theaters in the late 1960s and early 1970s. For years, short pornographic films, often called “stags,” had played in arcades, peep shows, and private homes. In the 1960s, loosely plotted films with female nudity and simulated heterosexual intercourse were introduced to small urban theaters and rural drive-ins—about six hundred venues by 1969. Feature-length pornographic films became fashionable—and commercially feasible—after the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) abandoned its production code in 1968, which had forbidden the discussion of sexual topics, not to mention overt representations of sex, in American films. (In 1973, the MPAA adopted the age-based rating system.) In the early 1970s, straight, hardcore pornographic films moved from the backrooms of sex clubs and porn houses to neighborhood theaters, a phenomenon that became known as “porno chic.”19

Deep Throat and Behind the Green Door, both released in 1972, were two of the most popular feature-length pornos, each depicting explicit male-female oral and vaginal sex. Although it played on fewer theatrical screens, Nights in Black Leather (1973) was a popular gay adult film. During the 1960s, men cruised for sex with other men in theaters screening softcore pornography. Hardcore gay films in the early 1970s became an important form of gay male popular culture, even as they popularized a new stereotype of the macho, denim- and cowboy-boot-clad gay “clone.”20

The unexpected popularity of Deep Throat and Behind the Green Door normalized conversations about explicit sex acts and helped make straight porn acceptable for heterosexual middle-class Americans. Deep Throat earned an estimated $100 million worldwide, and its star, Linda Boreman (acting under the name Linda Lovelace), appeared on late-night talk shows and in mainstream magazines. The film featured Boreman as a woman whose clitoris was rather anomalously located in her throat. Adult film star Harry Reems played the physician who explained to Lovelace’s character why she found penis-vagina sex disappointing—news that led her to “deep-throat” a series of men, with orgasmic results for all involved. It was a premise that might be credited for acknowledging the importance of the female orgasm, albeit within a straight male fantasy that a man receiving fellatio had simultaneously satisfied his female partner.21

Behind the Green Door, a film about an extremely kinky orgy, included a trapeze scene in which white actor Marilyn Chambers simultaneously had intercourse with a Black actor named Johnnie Keyes, gave another man a blowjob, and manually stimulated two more men. The fetishized portrayal of Keyes as a “savage” African, wearing a bone necklace and face paint, epitomized a racialized fantasy common in pornography. (Interracial pornography more often featured scenes of white men dominating Black women and typically included both implied and overt violence.)22

The mainstreaming of hardcore pornography fired the political imaginations of Dodson and like-minded sex radicals. Pornography’s “fantasy dreams of expanded sexuality,” Dodson explained, were not only arousing but politically explosive. Her main inspiration on this point was the Austrian American psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich. He had studied with Freud, who believed that sexual desires were natural, and that repression led to a debilitated, neurotic, and impotent society. Too much repression, Freud explained in 1908, was the cause of such “perversions” as homosexuality and compulsive masturbation. Reich went several steps further. In The Function of Orgasm: Sex-Economic Problems of Biological Energy (1942), he warned that sexual repression was dangerous. Orgasm, by contrast, prepared the individual psyche for liberation. Even better known than Reich was his contemporary, Herbert Marcuse, another psychoanalyst. Marcuse argued that sexual repression fed authoritarianism, and that capitalism drained libidinous energies necessary for individuals to pursue the “Pleasure Principle.” The mantra that people should “Make Love, Not War” was not merely philosophical, then, but a plan to achieve global peace. Dodson interpreted these theories as more evidence that sex was the driving force in the human experience. Alluding to the Soviet Union’s economic plans, she added that in any revolution, “Those five-year plans have got to include orgasms.”23

In the fall of 1971, she traveled to the second Wet Dreams Film Festival in Amsterdam, a gathering of about four hundred people who watched the latest adult films during the day and gathered for drugs and group sex at night. Dodson was one of the invited judges, and she celebrated the festival’s hedonism, which culminated in a “superorgy” of about fifty people. “I was making love to people and I didn’t know their names and it didn’t matter you know,” she recalled. The parties at the festival affirmed an idea Dodson shared with contemporary sex liberationists: sex is social, a way of knowing a person and building a community. More often associated with some queer men’s sexual sociability, this relational view of sex inspired Dodson to seek erotic encounters with as many different people as possible.24

Back in the United States, Dodson created an especially interactive form of sex education: her “Bodysex” workshops, in which she helped other women learn about their bodies and practice masturbation techniques. She hosted the workshops in her apartment, greeting each woman at the door fully naked and inviting them to leave their clothes on hooks in her entryway. Nudity was part of Dodson’s method for helping women move past any shame or ignorance they had about their bodies. Dell Williams, who attended a workshop in 1972, initially recoiled: “since I had never been conditioned to feel comfortable with anyone in the nude, I was not prepared to be nude among complete strangers, all women or no.” But Dodson set her at ease: “To be with her was to share her sense of joy and aliveness, her environment, her sexuality, HERSELF.” Dodson reinforced the idea that her workshops offered women the opportunity to shed a lifetime of learned inhibitions. It was a scene that Angela Heywood, in her late-nineteenth-century quest for sexual candor, could only have imagined.25

Participants in Bodysex workshops discussed how they felt about their bodies, their degrees of satisfaction with their orgasms, and their fantasies. The workshops had several standard elements. “Genital show and tell” asked each woman to hold up a mirror to her genitals, which were illuminated by a desk lamp for everyone else in the room to view and appreciate. Williams admitted that she was initially shy about showing her vulva to strangers: “But Betty made it easy by commencing to show her own genitals first in such a matter-of-fact manner that you would think she was demonstrating a new coffee pot.” Dodson and Sheila Shea, who helped run the workshops, masturbated with vibrators in front of the group. Dodson expanded on these ideas in Liberating Masturbation, her self-published guide for women, which sold thousands of copies.26

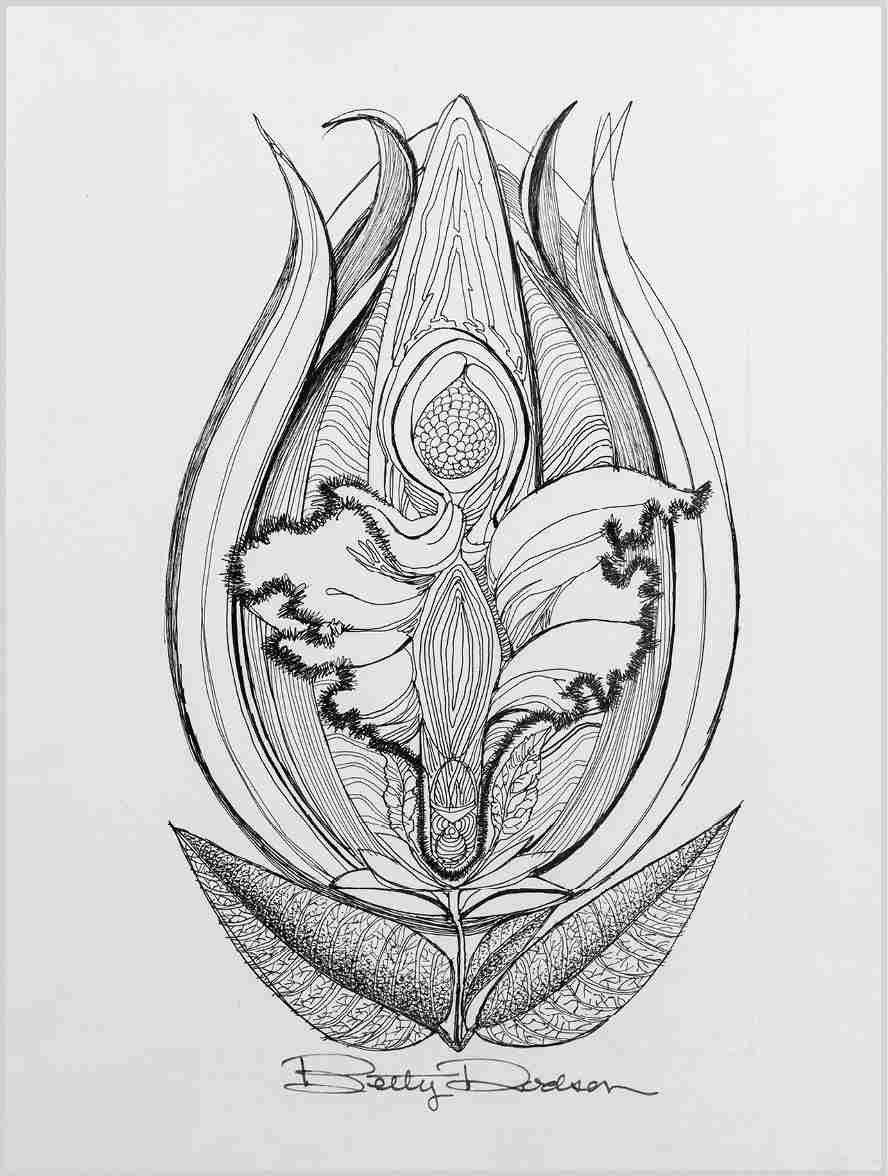

Dodson’s self-published booklet, Liberating Masturbation, was her manifesto about the necessity of sexual self-pleasure for women’s liberation. This cover art captured Dodson’s artistic sensibility and humor: an ornately detailed flower blossom that represents female genitals.

Groups of women around the United States had begun to perform cervical self-examinations in the late 1960s and 1970s, an element of a women’s health movement that criticized the male-dominated medical profession for keeping most women ignorant about their own bodies. In 1971, a group of feminists who called themselves the Boston Women’s Health Collective distributed a mimeographed guide to women’s health that their members had written, which became the blockbuster book Our Bodies, Ourselves (1973). Across the United States, women in consciousness-raising groups examined their cervices and educated each other about gynecological conditions. Dodson was not passing around a speculum, but her call for women to know their own bodies echoed the broader women’s liberation movement.27

Over the next four decades, Bodysex workshop fees supplemented the modest living that Dodson made as a lecturer, writer, and educator. News about the workshops circulated in feminist newsletters. She did not keep records of the participants in her workshops, but the most outspoken fans of them were white, pro-sex feminists like Dodson.28

Betty Dodson was in her early forties when she joined the resurgent feminist movement, fully convinced that orgasm was the foundation of a better world. Drawing on Reich, she explained that “the economic and political control of women is based on sexual repression.” That argument appealed to many women, but Dodson’s insistence that orgasm was a catalyst for revolution offended activists who prioritized class-, race-, and gender-based analyses of their oppression.29

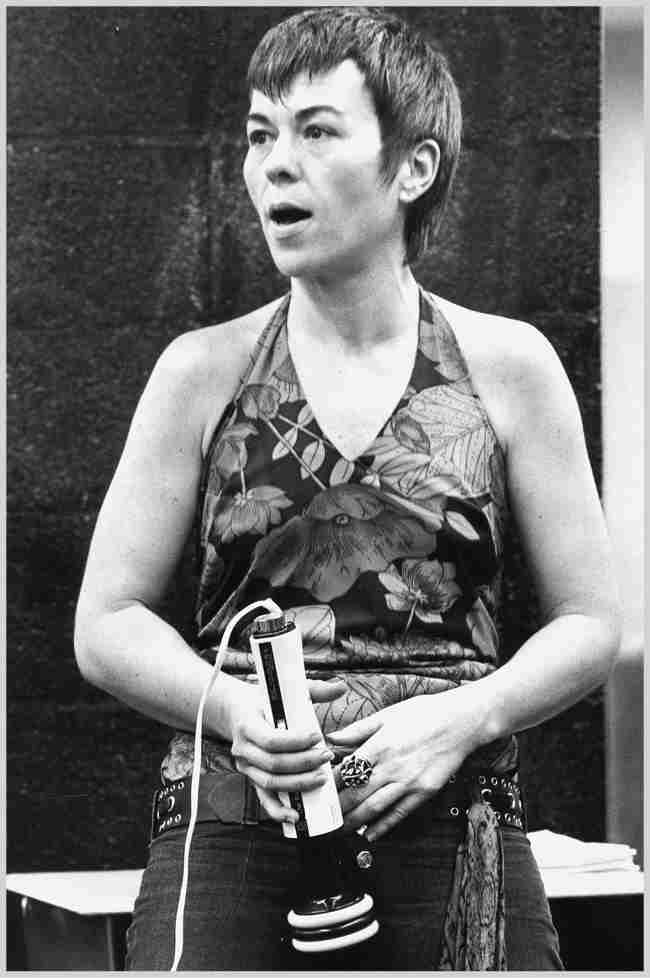

Betty Dodson’s presentation at the NOW Sexuality Conference in New York City in 1973 introduced her to an influential cohort of feminist women committed to including sexual liberation within the women’s movement. Here, Dodson demonstrates how she masturbated using a Hitachi Magic Wand vibrator.

Dodson’s philosophy found a warm welcome among the feminists who gathered for NOW’s “Sexuality Conference” in June 1973 in New York City. NOW had been founded in 1966 to advance gender equality, and by 1973, it addressed a range of feminist issues. Judy Wenning, the president of NOW’s New York chapter, explained that the conference’s goal was to “encourage women to see themselves not as heterosexual or homosexual or bisexual, but as sexual.” Among the more than one thousand women who attended the conference’s lectures and workshops, Dodson’s Sunday-morning presentation became legendary.30

She showed slides of her artwork, images of genitals in medical texts and pamphlets, and then “huge, full-color, extreme-closeup slides of the individual genitals of about ten women who’d taken her workshops.” With her trained eye, she invited her audience to see each vulva as a work of art, describing one with elaborate folds as “baroque,” another one with a narrow, elongated shape as a “Classical Cunt,” and a hairless one as “Danish modern.” (All of her examples drew from European art styles.) “Betty emphasized the special beauty of each woman’s skin texture and hair color,” one attendee recalled, “and the unique shape of each clitoris, vagina, and anus . . . When she finished, the women applauded and whistled triumphantly.” The crowd rewarded her with a standing ovation.31

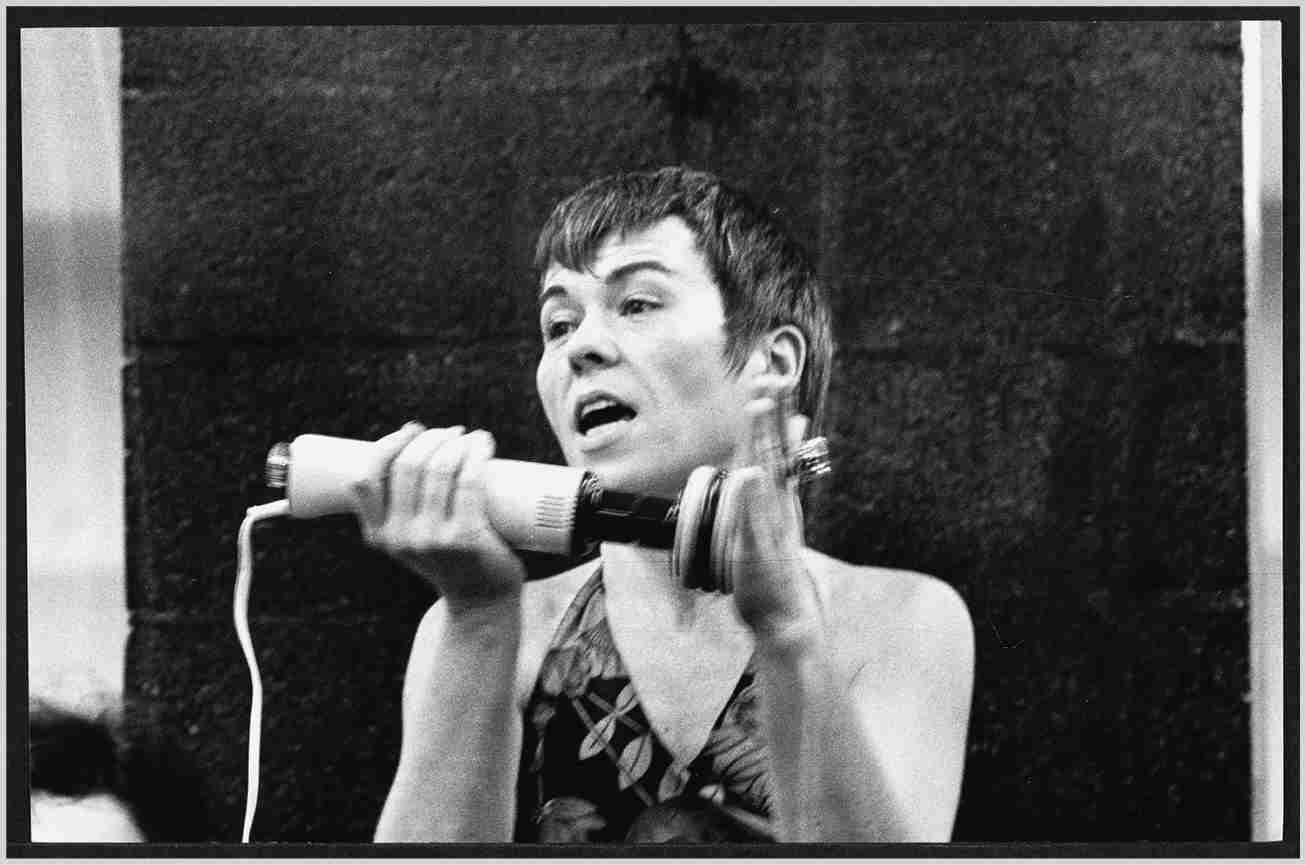

In this additional image from the NOW Sexuality Conference, Dodson seems to have turned on the vibrator, demonstrating its movement against her hand. Her matter-of-fact presentation, with photographs of female genitals and frank descriptions of masturbatory techniques, inspired women such as Dell Williams, who subsequently opened Eve’s Garden, the first sex shop for women, in New York City.

Williams was so inspired by Dodson that she opened Eve’s Garden, the first women-only sex store in the United States. Williams envisioned Eve’s Garden as “a comfortable place where women would be able to buy vibrators without embarrassment, harassment, or hassle.” Williams’s store was one of a host of new businesses and organizations created by and for women in the 1970s. Many of these enterprises operated on a collectivist ethos, eschewing a drive for profits in favor of free educational workshops and community-building.32

Dodson lived an increasingly bicoastal life, splitting her time between her Bodysex workshops in New York and a group of sexual iconoclasts in San Francisco. She earned a PhD in sexology from the Institute for the Advanced Study of Sexuality, an unconventional (and unaccredited) graduate program that operated out of a “seedy” San Francisco storefront. The Institute’s signature instructional tool, Sexual Attitude Restructuring (SAR), entailed watching hours upon hours of commercial porn to “desensitize” participants to the choreographed erotic configurations the films portrayed. SAR continued with “sensitization,” as they watched verité sex films, non-commercial productions featuring individuals, couples, and groups having sex without the artificial elements of studio lighting or professional camera work. Students were encouraged to express their own sexual desires as they watched, with the event invariably resulting in what participants affectionately called the “Fuckorama.”33

This was a far cry from the priorities of sex researchers of the time. In the 1970s, sexologists named two new categories of sexual disorder: inhibited sexual desire and sex addiction. While a later generation of activists would name asexuality as a category of identity (especially after the 2014 publication of Julie Decker’s book, The Invisible Orientation: An Introduction to Asexuality), sex therapists and researchers in the 1970s viewed it as one of several diagnoses of disordered sexual desire they observed in their patients. To Dodson, lack of interest in sex was a hang-up, and something to be gotten over as quickly as possible.34

Such sexual hedonism deeply offended some feminists, who found it not simply tangential but antithetical to the movement’s aims. “There’s a danger,” an editorial in a feminist newsletter noted, “of confusing self-gratification with liberation.” In 1975, feminist Ti-Grace Atkinson forcefully argued that the women’s movement was never about sexual liberation, an idea that merely reproduced “an old Left-Establishment joke on feminism: that feminists were just women who needed to get properly laid.” Atkinson blamed the patriarchy for making sex appear to be far more important than she believed it truly was. Valerie Solanas, a like-minded radical, described sex as “a gross waste of time.” Dodson, of course, did not want simply to “get laid” but to give other women the knowledge and skills they needed to enjoy orgasm whenever and wherever they wanted to.35

Nor could many feminists ignore sexual violence to the extent that Dodson had. In consciousness-raising groups and “rap sessions,” many women divulged their personal experiences with intimate-partner violence and sexual assault. Awareness of violence against women as a social and political matter, rather than merely an individual one, motivated thousands of women to become anti-rape activists. Helping women escape domestic violence and heal from rape became a unifying cause within an otherwise fractious feminist movement. By 1976, four hundred feminist-led rape crisis centers existed across the country.36

Yet even approaches to sexual violence revealed divisions among women. In Susan Brownmiller’s landmark treatise about rape and gender, Against Our Will (1975), she argued that rape was an expression of male power over women, of the desire of “all men to keep all women in a state of fear.” Brownmiller’s refusal to concede that some people, especially nonwhite men, suffered under a different set of assumptions—that, for instance, there was a long history of false rape accusations against Black men—dismayed Black women who insisted on a politics that foregrounded race as well as sex.37

What became known as the “sex wars” pitted “pro-sex” feminists like Dodson against “anti-porn” feminists. Anti-porn activists argued that all pornography abused women and that sadomasochistic (SM) erotic role-play reproduced women’s subordination. According to Robin Morgan, a prominent radical feminist, “pornography is the theory, and rape is the practice.” Pro-sex feminists countered that these distinctions between “good” and “bad” sex were simply new ways to control and shame women. As the sex-radical feminist Ellen Willis asserted, the sexual revolution for women entailed not “the simple absence of external restrictions—laws and overt social taboos” but the “social and psychological conditions that foster satisfying sexual relations.”38

The exuberantly public sexuality that Dodson and other sex liberationists celebrated struck anti-pornography feminists as evidence of women’s ongoing subjugation, especially when children were involved. They were quick to point to such films as Pretty Baby (1978), in which a preadolescent Brooke Shields played a child prostitute in a New Orleans brothel, and Taxi Driver (1976), in which Jodi Foster portrayed a teen sex worker. Shields’s seductive ads for Calvin Klein jeans in the 1980s similarly registered with these critics as attempts to transform female children into objects of desire. Black feminists, meanwhile, pointed out that anti-pornography feminists, in their outrage over the sexualization of female minors, ignored how vulnerable girls and women of color were to sexual exploitation and to abuse by police officers. Stepped-up law enforcement and morals reforms, they knew, had never made Black women or men safer.39

Dodson was undeterred. She explored her affinity for “kink,” and by 1982 she was experimenting with SM, which involved consent-based submission and punishment. Dodson now identified as a “bisexual lesbian” who acted as the dominant, or “Domme,” partner during SM. Adopting an androgynous style, she reveled in her self-presentation as “a leather dyke” for whom leather harnesses and toys were major turn-ons. Lesbian SM practitioners rejected the idea that role-playing was inherently oppressive, a mere mimicry of heterosexual power relations. Far from a re-creation of violence, they argued, SM provided a safe opportunity for women to experiment with partners they trusted. Some even described SM as a way for women to heal from patriarchy.40

Gayle Rubin, a leading feminist theorist and founding member of the lesbian SM group Samois in San Francisco, assailed the idea that sexual pleasure was “a male value and activity.” Rubin was dismayed by lesbian feminists who attempted to create a sexuality free of power dynamics. These women, Rubin argued, treated sex as “something that good/nice women do not especially like.” A strain of lesbian feminism that focused on intimacy more than orgasm, she warned, threatened to derail women’s liberation. She and other members of Samois also rose to the defense of “gay lovers of youth.” Boldly rejecting the idea of an “age of consent,” Samois supported “young people’s right to complete autonomy, including sexual freedom and the right to have sexual partners of any age that they wish.” The enforcement of statutory rape laws, Rubin argued, simplistically defined “a fully consensual love affair” between an adult and a minor as assault.41

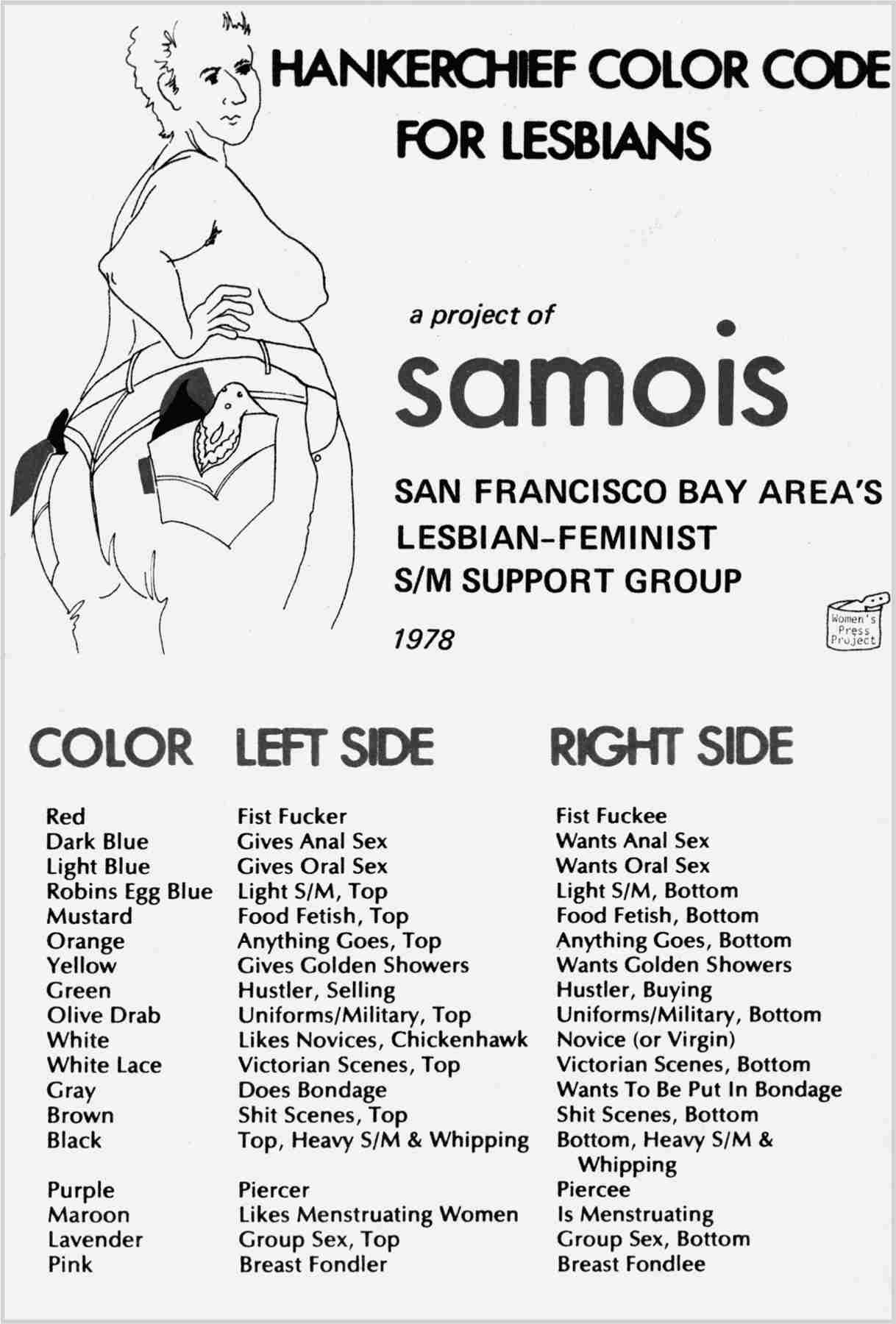

Lesbian feminists interested in sadomasochism, bondage, and kink created a group called Samois in San Francisco during the late 1970s. This “Handkerchief Color Code” was both playful and informative, offering women interested in SM sex a way to communicate their erotic preferences to potential partners.

Some feminists considered SM, pornography, and a more general emphasis on orgasm as frivolous distractions from the sexual perils that women faced. The activist group Women Against Pornography became the face of this opposition in the “feminist sex wars” of the early 1980s. Eugene Gordon, Women Against Pornography, Greenwich Village, New York City, 1985, Eugene Gordon Photograph Collection, 87652d, New-York Historical Society.

Conflicts over SM and pornography moved from the pages of feminist publications to the streets of New York City in 1982, when protests erupted at the Scholar and the Feminist IX conference at Barnard College on the theme, “Towards a Politics of Sexuality.” As attendees gathered for lectures and workshops, demonstrators massed outside the building. Days earlier, college administrators had seized 1,500 copies of the conference “diary,” a sixty-page booklet with abstracts of the talks. Members of a group that called itself the Coalition of Women for a Feminist Sexuality and Against Sadomasochism handed out leaflets denouncing the conference for promoting sadomasochism and seeking “an end to laws that protect children from sexual abuse by adults.” They made these claims even though the conference was not remotely devoted to those topics—it instead broadly considered the tension between sexual pleasure and danger from a feminist perspective. This animosity soured relationships among American feminists. Southern novelist Dorothy Allison, who was named in the protestors’ pamphlet as the founder of the Lesbian Sex Mafia (which she was), subsequently published a poetry volume titled The Women Who Hate Me.42

Support for Dodson’s erotic vision emerged not from mainstream white or women-of-color feminism but a small network of pro-sex feminists. This included not only Samois but also a group of San Francisco lesbians who launched On Our Backs, a magazine whose title poked fun at off our backs, a redoubtable lesbian separatist publication. Articles and pictorials in On Our Backs celebrated sex play with dildos, strap-ons, nipple clamps, pornography, group sex, and SM. Sex writer Susie Bright, who considered Dodson a personal and professional inspiration, had first learned about sex toys as an employee of Good Vibrations, the first sex shop for women in San Francisco. Her column in On Our Backs, “Toys for Us,” often included reviews of sex toys written with unapologetic enthusiasm for erotic adventure. Bright soon had a regular column in Penthouse Forum, a hardcore pornographic magazine for men.43

Dodson and other pro-sex feminists similarly supported pornographic videos written and directed by and for women. The invention of the VCR in the mid-1970s made the production of pornographic films much cheaper, opening the market to female directors and producers whose movies would never have turned a profit in a traditional theater. After a slow start, an estimated 26 million VCRs had been sold in the United States by 1985, and there were approximately 22,000 video rental stores across the country. As many as half of all videotapes sold in the mid-1980s were adult films. In December 1991, Dodson proudly presented Selfloving, a candid video recording of one of her Bodysex workshops, including the “genital show and tell” and demonstrations of Dodson’s masturbation techniques. It premiered at Eve’s Garden.44

The anti-pornography movement meanwhile tried to ban the sale and distribution of pornography. Catharine MacKinnon, an attorney who advocated for local anti-porn regulations in the 1980s, argued that porn “sexualizes women’s inequality” and “increases attitudes and behaviors of aggression and discrimination, specifically by men against women.” A New York–based group that Dodson loathed, Women Against Pornography (WAP), looked to the federal government to suppress porn. A coalition of odd bedfellows, WAP included marquee feminists such as Gloria Steinem, the anti-pornography zealot Andrea Dworkin, and a cohort of Catholic and evangelical Protestant women.45

In 1985, when Attorney General Edwin Meese announced the formation of a Commission on Pornography, WAP provided the commission with a list of potential witnesses, each prepared to testify at federal hearings that pornography had hurt them personally. (Many of these activists were still angry about the Presidential Commission on Obscenity and Pornography appointed by President Lyndon Johnson in 1967. That commission’s 1970 report declared that it had found no evidence that pornography caused harm and recommended the repeal of all laws that restricted adults’ access to sexually explicit materials.) Several women testifying before the Meese Commission described years of sexual, emotional, and physical abuse from husbands “addicted” to pornography. The 1,960-page Final Report (1986) concluded unequivocally that pornography instigated violence against women. This view persisted on the political right for decades; the 2006 GOP platform declared pornography a “public health crisis” that was “destroying the lives of millions.” The idea that pornography is fundamentally harmful, especially to children, remains a contentious policy issue across the political spectrum.46

Government censors singled out homoerotic art for special criticism. In 1989, new federal legislation barred the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), a federal agency, from supporting “obscene” projects “including but not limited to sadomasochism [and] homoeroticism.” The NEA pulled its funding from artists who created sexually explicit work, including the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, who often portrayed scenes of male homoeroticism and sadomasochism. In 1990, Dennis Barrie, the director of the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati, was indicted on obscenity charges for mounting a Mapplethorpe exhibit. Artists’ representations of queer pleasure were far more vulnerable to claims of “obscenity” and to censorship than were productions focused on heterosexuality.47

Outcries over masturbation in the 1980s revealed how dramatically the boundaries of acceptable sexual speech had narrowed since the heyday of sexual liberation in the 1970s. Joycelyn Elders, President Bill Clinton’s surgeon general and the first Black woman to hold that position, was forced out in 1994 after she spoke in favor of sex-education programs that included information about the benign effects of masturbation. Even sex therapists warned that masturbation, if it became a “compulsion,” indicated that an individual suffered from “sex addiction.” Dodson’s boast that she spent two hours a day masturbating “and designing sex rituals” remained a challenge to the status quo.48

Dodson’s message about the centrality of sexual pleasure to human fulfillment nevertheless survived. Four lesbian sex magazines started publication in the mid-1980s. Their success reflected the increasing confidence of queer women and inspired new experiments with feminist erotica. “Sex-positive” feminism laid the foundation for “third wave” feminism in the 1990s, which viewed female erotic pleasure as the cornerstone of women’s equality. In homegrown “zines” and punk-rock “Riot Grrrl” bands, girls and women proclaimed their erotic autonomy.49

Dodson championed extraordinary sexual candor throughout her life, but she never seemed to grasp the importance of race for American sexual norms. She ignored the significance of racial stereotypes to sexual fantasies, even as she fetishized the ideal of the well-endowed Black man. As Dodson critiqued American prudishness, she overlooked the disparate ways in which ideals of white female purity depended on contrasting assumptions about Black and Asian women’s sexual availability. A cringeworthy moment of racial obliviousness occurred during the “genital show and tell” of a video-recorded workshop she hosted in the 2010s. On this occasion, Dodson attempted to tease the only non-white participant, a woman of Asian descent, by quipping that everyone assumed that her vagina opened “sideways.” Although Dodson likely believed that invoking this racist trope about Asian women’s bodies demonstrated her disdain for stereotypes, the woman in question was clearly uncomfortable.50

Dodson’s mission to educate women about their bodies remained relevant. On Goop Lab’s episode with Dodson in 2020, host Gwyneth Paltrow squealed about their opportunity to talk about “vaginas!” Dodson met Paltrow’s gaze with an unamused stare. “The vagina is the birth canal only,” she corrected. “You want to talk about the vulva.”51