Chapter 15

Irresponsible Intercourse

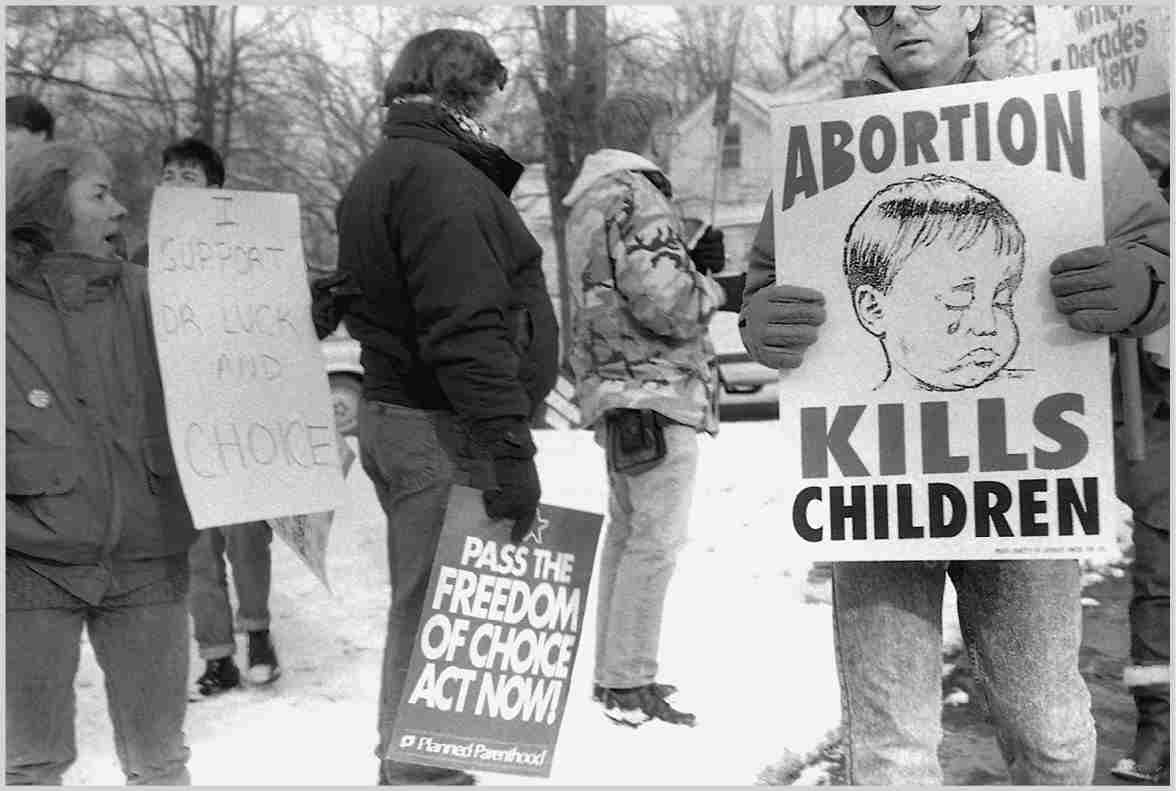

Members of WHAM! (Women’s Health Action and Mobilization) counter-protested when members of Operation Rescue demonstrated outside the home of abortion provider Dr. Bernard Luck in Monroe County, New York, in 1992. Luck and other providers were the targets of constant harassment and, in some cases, murder, by anti-abortion extremists.

The fire that tore through the Blue Mountain Clinic (BMC) in Missoula, Montana, in March 1993, fed by gasoline poured over the building’s interior that ignited and blew out the building’s windows and collapsed its floors and walls, was the worst in a series of attacks on one of only two abortion clinics in the state. Picketers with signs calling abortion “murder” had regularly gathered outside the clinic since the late 1970s. They accosted women walking in and tried to persuade them to change their minds. Patients struggled to make their way to the clinic’s doors through a gauntlet of abortion opponents.1

Over the years, the protests became more intrusive, with demonstrators attempting to storm the clinic. Local members of Right to Life and other anti-abortion groups denied culpability after the firebombing that destroyed the BMC in 1993. They repeated an argument that major anti-abortion groups had been making since the 1970s: it was abortion, not the protests against it, that was violent.2

Conspicuously absent from the local conversation about the 1993 fire was a Catholic woman named Suzanne Pennypacker Morris, who was Missoula’s most vocal and influential opponent of abortion. She led the first picket of the Blue Mountain Clinic in 1978 as head of the local chapter of the national organization Right to Life (RTL). The anti-abortion movement she joined had mobilized in the late 1960s, and it was a force in American life by the time the Supreme Court’s decision in Roe v. Wade (1973) ensured a constitutional right to an abortion as a matter of privacy.3

Morris played no part in the 1993 attack, but she helped build the ideological foundation for anti-abortion protests in her state. Although newspapers identified Morris as a “homemaker,” she was also a seasoned activist and political operative. To Morris and her allies, abortion threatened the lives of “unborn humans” and it undermined the very meaning of male and female, of heterosexuality, and of Christian virtue. Betty Dodson’s celebrations of sexual liberation and Kiyoshi Kuromiya’s organizing for gay liberation struck these activists as not only hedonistic but immoral. In 1979 Morris challenged a reporter with a rhetorical question: “Are women really asking to be as sexually irresponsible as men are? It would be much nicer if we could make men more responsible.” That argument echoed the slogans of purity reformers in the late nineteenth century, who advocated for “a white life for two” to make premarital chastity the norm for men as well as women. Women in the anti-abortion movement often portrayed abortion-seeking women as victims of callous men, desperately seeking the protection and support that dutiful husbands should have provided. Morris’s comments reflected another strain in the movement, one that construed abortion as the craven choice of promiscuous women.4

In step with the National Right to Life leadership, Morris called for a constitutional amendment to ban abortion and in the meantime supported incremental changes to impede access. She lobbied elected officials and even ran for Congress, twice, as an anti-abortion Republican, losing in the primaries in 1980 and 1982. Her opposition to abortion was rooted in her Catholic faith, which taught her that life began at conception and that the quest for sexual freedom was irresponsible. But Morris’s zeal also flowed from her combative temperament. She loved the fight.5

It has become common to describe abortion supporters and opponents as “single-issue voters” in U.S. elections. That framing overlooks how the abortion issue became a referendum on the sexual revolution, gay rights, and feminism. Abortion opponents described the procedure as an assault on the “American family” because, they argued, it untethered reproductive sex from marriage, women from men, and men from their responsibilities as family breadwinners. Abortion struck at their beliefs that the conventionally gendered, heterosexual family held the nation together. It was a threat on par with new “no-fault” divorce laws (first in California, and soon in many other states); increasingly visible gay and lesbian communities; and the feminist demand for an end to conventional gender roles. As such, an individual’s sexual decisions were matters of public concern, requiring community vigilance and, when necessary, state intervention. This worldview rejected the modern understanding of desire as a discrete aspect of human experience, arguing instead that sexual behaviors indicated how well a person understood and followed Christian values.6

Anti-abortion activists depicted the fetus as the brutalized victim of sexual excess. They also attacked the abortion rights movement as a feminist plot to undermine male-female reproductive marriage. The combination of these two images—slaughtered infants and promiscuous women—provoked righteous fury on the right. Casting abortion as murder riled up rank-and-file activists and extremists alike. Their crusade was—and remains—an ardent critique not only of women’s sexual liberation but of the legitimacy of all sexualities and genders other than a heterosexual, marital, reproductive norm.

Montana’s legislature first restricted abortion in 1895, just six years after the territory became a state. The state of Montana existed because of wars against local Indigenous nations. With the support of the federal government, white settlers pushed Crow, Blackfeet, Northern Cheyenne, and other Native people onto reservations and carved up tribal lands into small “allotments.” Native leaders agreed to land cessions that they hoped would allow them to live in peace, but the allotment process strained their kinship networks and further impoverished them.7

The 1895 law punished not only the abortion provider but also the woman who agreed to “any operation, or to the use of any means whatever, with intent thereby to procure a miscarriage.” (In practice, Montana providers were probably prosecuted more often than their patients, as was the case elsewhere.) Montana’s anti-abortion law was part of a wave of new state-level restrictions on abortion throughout the United States. Inspired by the likes of Horatio Storer, who defined abortion at any stage in a pregnancy as murder, state legislators rejected the idea that no “life” existed until quickening.8

Little had changed in the state’s abortion laws by the time of Suzanne Pennypacker’s birth in 1944 in Missoula. Montana’s revised criminal code of 1947 permitted abortion only when the procedure would save the life of the pregnant person. Initially, the determination of whether a pregnancy endangered a life was left to the attending physician’s discretion. Contraindications included everything from cardiovascular disease to diabetes or psychiatric conditions. Over time, such “therapeutic abortions” in hospitals became increasingly rare. Dr. James Armstrong, a family physician who provided women with reproductive healthcare, recalled only one therapeutic hospital abortion in the 1960s in northwestern Montana, where he practiced, “and that was done as a hysterectomy, [on] a married woman with a brain tumor.” Improved surgical techniques and medical interventions weakened the case that an abortion was necessary to save a woman’s life. Hospital administrators instituted new “therapeutic abortion committees” to ensure that only the direst cases met their criteria.9

Maternity homes and illegal abortions were the alternatives for a Montana woman who did not want to continue a pregnancy. Maternity homes were privately operated residences and training schools, run by religious or social welfare organizations. The homes promised to provide an unmarried pregnant woman with a discreet residence, teach her basic domestic skills, and facilitate the child’s adoption. Other people simply broke the law. At least thirty physicians, midwives, and untrained practitioners performed abortions in Montana between 1882 and 1973. Some of them undertook this illegal work to help desperate women. Other abortion providers exploited women for financial gain. During his medical residency in the 1950s, Armstrong cared for a woman who became fatally septic after a botched abortion. Decades later, after a long career providing abortions to women in Montana, he remembered every detail of that patient’s suffering and his inability to prevent her death.10

Armstrong’s harrowing experience was unfortunately common among medical providers of his generation. Thousands of women died each year from illegal abortions in the United States. Lower-income women who had little access to medical care or to reliable contraceptives were among the most vulnerable, taking terrible risks to end unwanted pregnancies. A physician at a family planning program in Louisiana described patients who were “very carved up—[from] very crude abortions—knitting needles, cloth packing,” he recalled. “And we see them coming in highly febrile, puerperal discharge in the vagina, germs in their blood, blood poisoning, septicemia, and those who survive have a very high probability of being reproductive cripples.”11

That misery prompted efforts to refer and transport women to safe abortion providers. Volunteers in Missoula helped women pay for travel to places where abortion was legal, initially to Colorado, which passed a narrow therapeutic abortion law in 1967, and soon to Washington state, which in 1970 repealed its abortion ban by popular referendum. Joan McCracken, a nurse and mother of five who ran the women’s health clinic in Billings, Montana, found additional support from the Clergy Consultation Service (CCS), a network of Protestant ministers, Reform rabbis, and even a few Catholic nuns who created a national abortion referral service and travel fund that aided hundreds of thousands of women between 1967 and 1972.12

Access to safe, legal abortions across the United States arrived with the Supreme Court’s majority opinion in Roe v. Wade, issued in January 1973. The opinion emphasized the importance of both competent healthcare and privacy; the justices did not defend access to abortion using the language or arguments of women’s liberation. Roe prohibited state-level restrictions on abortions in the first trimester of pregnancy (up to twelve weeks after the onset of the person’s most recent menstrual period) and allowed states to regulate second-trimester abortions only under limited circumstances. After Roe, many states, including Montana, mandated that second-trimester abortions, typically achieved through saline installation, be performed in hospitals. In fact, anyone who needed an abortion in Montana, even very early in a pregnancy, was sent to a hospital in the years immediately following Roe, because the state had no freestanding clinics for abortion care.13

The Blue Mountain Women’s Clinic, named after the mountain peak that was visible from downtown Missoula, opened its doors in February 1977 after members of a feminist collective, the Women’s Place, decided to expand reproductive healthcare options for Montana women. Clients came in for pap smears, prescriptions for contraception, and vasectomies. (Within a few years, the name was changed to Blue Mountain Clinic to reflect that it served people of all genders.) The clinic hosted workshops on topics ranging from fibromyalgia to herpes to menopause. And once a week, a physician at the clinic performed abortions for people in the first trimester of a pregnancy. Across the country, activists surveyed similar challenges and established hundreds of freestanding clinics.14

Over 650 women had abortions at the Blue Mountain Clinic during its first year. Patients ranged in age from fourteen to forty-eight, and they sought first-trimester abortions for a variety of personal reasons. The BMC kept costs low, charging $165 for an abortion that would cost $500 at Deaconess Hospital in Billings. Patients at the BMC received local anesthesia before undergoing a five-minute procedure known as vacuum aspiration, which removed all fetal tissue from the uterus.15

Suzanne Pennypacker Morris was paying attention to news about the clinic, nicknaming it, disparagingly, “the Blue Mountain Abortion Clinic.” For her and thousands of other Americans, no matter what else the clinic did to provide healthcare, its abortion services tarnished the entire enterprise. She and other anti-abortion activists were intent on making “abortion” a dirty word that bore no relation to women’s well-being.

Catholic women such as Suzanne Pennypacker grew to adulthood learning that abortion was singularly evil. Pope Pius XI’s 1930 encyclical, Casti Connubii, asserted the Church’s belief that both contraception and abortion were sinful violations of God’s “natural law,” a position sustained in Pope Paul VI’s Humanae Vitae in 1968. Still, most American Catholics at the time practiced some form of contraception. In 1968, when she was twenty-four, Suzanne married Patrick Morris, and they soon had three daughters. Patrick worked for the National Forest Service, and his job took them from DC to Dayton, Ohio. Caring for three young children, Suzanne was not in the paid workforce. That said, she found her calling outside of her home. Six years into her marriage and about a year after the Roe v. Wade decision, Morris first appeared in a local Ohio paper as a fierce opponent of “the slaughter of babies” in area hospitals that performed abortions.16

Morris joined thousands of other American Catholic women who supported crisis pregnancy centers (CPCs). A group called Birthright operated many of these centers; Morris encouraged pregnant women in distress to call Birthright rather than Planned Parenthood. These centers looked like women’s health clinics but functioned primarily to discourage women from seeking abortion care. CPCs typically offered free pregnancy tests and presented clients with extensive print, photographic, and eventually video evidence of fetal development while they waited for their results. For the sake of “saving babies,” CPC volunteers rented or used donated space in high-poverty urban neighborhoods; women there were more likely to need a free pregnancy test. CPC activists believed that they could teach one woman at a time that life began at conception. Initially, Catholic women led most CPCs in the United States. These centers eventually became places for Catholics and evangelical Protestants to join forces.17

Morris led pickets in October 1975 and January 1976 at the Dayton Women’s Health Center, where protesters carried signs that read “Ten Babies Will Die Here Today.” She churned out letters to the editors of local newspapers in which she defended the civil rights of “preborn human beings.” “A totally unique human being exists at conception,” she argued, comparing Roe to the infamous 1850s Supreme Court opinion in Dred Scott v. Sandford, which argued that African Americans could not be citizens because they were not “people” in the eyes of the Constitution’s framers. Morris parroted the national anti-abortion movement’s rhetoric when she maintained that it was just as wrong in the 1970s to deny that the fetus was a rights-bearing person as it had been in the 1850s to deny Black humanity.18

It was a provocative thesis: if abortion violated the civil rights of a fetus, then the movement to stop it was an extension of the civil rights cause. Starting in the late 1960s, Catholic leaders had appealed to the social justice wing of American Catholicism and to Protestants (few of whom, at the time, opposed abortion on religious grounds) to view abortion as a matter of civil rights. They described abortion as a singularly violent violation of individual rights rather than as disobedience to papal decrees. As Morris wrote in one 1976 letter, “Hopefully, it will not take as long to extend civil rights to the unborn as it has to our black brothers.” Morris seems not to have written publicly about civil rights aside from her defenses of the unborn. In another letter to the editor, she analogized aborted fetuses to European Jews killed in the Holocaust, already a common rhetorical gambit among abortion opponents, as it remains today.19

Rights language that appeared in anti-abortion campaigns, however, did not lead anti-abortion activists into actual civil rights work. Some leaders in the anti-abortion movement had participated in civil rights and antiwar demonstrations, but many others were the same people who had recently lost the battle over racial segregation. In the abortion battle, they cast themselves as latter-day abolitionists, not segregationists, who defended Black people by seeking to protect unborn Black children.20

In doing so, some white conservatives forged alliances with Black nationalists who considered abortion a form of “genocide.” Those arguments echoed the pronatalism of Black nationalist Marcus Garvey in the 1910s and early 1920s. In the late 1960s, Black nationalist organizations, including the Black Panther Party, described birth control as a tool of white supremacists to kill off Black people. Even some male leaders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Urban League, both mainstream civil rights organizations, reversed their earlier support for women’s access to safe contraceptives and to abortion. Black people who supported birth-control clinics, and Black women in particular, rejected those criticisms. In Pittsburgh, Black women opened a birth-control clinic over the opposition of a local Black minister. Confrontations erupted among the Puerto Rican Young Lords in New York City when male leaders opposed birth control and abortion access. Women in the movement successfully pushed the group to recognize the value of contraception for their liberation.21

What many anti-abortion activists shared—and what remained consistent across their involvement in various causes—was sexual conservatism. They largely opposed the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), gay rights, and other movements for sexual equality. As the newsletters of a Catholic anti-abortion group in Michigan put it in 1972, abortion was “a symbol of addiction to unrestrained sexual license and an abdication to [sic] personal responsibility in the sphere of reproductive conduct.” Those political priorities contributed to the socially conservative tilt of the Republican Party in the 1970s, as it persuaded many white Catholic voters, long-standing supporters of the Democratic Party, to see their cultural values reflected in the GOP’s battle against socially “permissive” liberalism. Rights talk also secularized the abortion issue, shifting it more decisively from a matter of Catholic theology to a referendum on universal human dignity. These shifts—of large numbers of Catholics into the Republican Party and of evangelical Protestants into the anti-abortion cause—originated at the grassroots, as voters responded to the anti-abortion movement’s portrayal of abortion as the murderous denial of the fetus’s civil rights.22

Morris was something of an exception. She joined International Feminists for Life, a group of white Catholic women who simultaneously opposed abortion and supported the ERA. She seems to have desired sexual equality without sexual liberation. A leader of Feminists for Life described abortion as a tool of men’s exploitation of women, manifesting “the idea that a man can use a woman, vacuum her out, and she’s ready to be used again.” Whatever her feminist inclinations, Morris remained adamantly opposed to abortion. At a rally in Dayton, she called out the National Organization for Women for “deceiving women into thinking that their equality can only be achieved over the dead bodies of unborn children.” Feminists for Life mocked the idea of a woman’s right to reproductive self-determination, characterizing it as a specious justification for immoral behavior. “Abortion—A Woman’s Right to Choose to Kill,” a protester’s sign read.23

The Morris family relocated to Missoula in 1977 to further Patrick’s career with the Forest Service. Suzanne soon took the helm of both the Missoula and the Montana Right to Life chapters. She served in leadership roles from 1977 to 1984, increasing the relatively small membership of Missoula RTL from 50 or 60 people in 1974 to about 100 people in 1979. Morris claimed to speak for a majority of women in her state and across the country, but national polls suggested otherwise. In a February 1976 CBS/New York Times poll, 67 percent of respondents supported legal abortion.24

At that first picket of the Blue Mountain Clinic, in December 1978, Morris hosted a “pray-in” for fetuses aborted there “and all others who die in abortion.” By mourning outside of women’s health clinics, Morris and other members of RTL gave visible expression to the belief that pre-viability fetuses were rights-bearing people. In 1979 she led a Montana Right to Life rally that included posters displaying what one reporter described as “gruesome pictures of aborted babies.” It was a familiar tactic of the movement. Advances in ultrasound technology by then allowed abortion opponents to display images of fetuses in utero, a way to drive home their argument that fetuses were people. That visual evidence has remained central to the movement’s strategies ever since.25

Sexual restraint remained the anti-abortion movement’s primary advice for women who did not want to get pregnant (a view that, among other things, does not account for non-consensual sex). Planned Parenthood’s sex-education curriculum appeared to preach the opposite. As it stood, comprehensive sex education was relatively new, incorporated into middle and high school curricula in the 1960s and thereafter thanks to organizations such as the Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS). Shaped by the moderate ethos of its founder, Mary Steichen Calderone, SIECUS emphasized the importance of helping young people become sexually responsible adults capable of a healthy marriage. Typically provided in health classes, sex education followed a carefully designed curriculum. Middle schoolers learned about menstruation and nocturnal emissions, and high school students discussed contraception and sexually transmitted infections. These programs redefined sexual health, previously understood as the absence of disease, as “preventive medicine” that might help individuals build sexually fulfilling lives. Yet from the earliest iterations of SIECUS and other progressive curricula, sex education lesson plans infuriated certain parents—usually but not always conservative Christians. These opponents argued variously that sex education programs were Communist, taught their children to be gay, sexualized very young children, exposed youth to pornography, and contributed to rising teen pregnancy rates.26

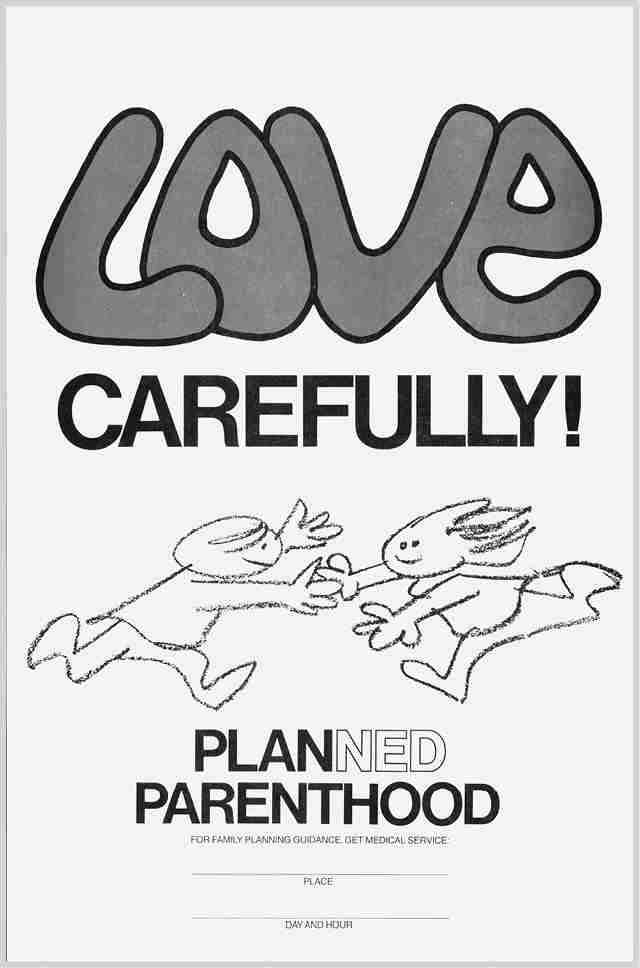

The Planned Parenthood Federation of America and its state branches created sex-education curricula that included information about human reproduction, contraception, and masturbation, among other topics. For anti-abortion activists like Suzanne Pennypacker Morris, Planned Parenthood’s associations with abortion provision overshadowed all other aspects of the group’s work. This PPFA poster was printed some time between 1965 and 1980.

Sex education was a new venture for Planned Parenthood Federation of America (PPFA). Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, PPFA had focused its resources on educating women about the birth-control pill and other contraceptive methods. Local chapters operated health clinics. The PPFA also advocated for “population control” around the world. Then, in 1979, PPFA created an education division, and some of the local affiliates launched sex-education programs of their own. Many of these curricula borrowed from a popular program created in 1971 by the Unitarian Universalist Association, About Your Sexuality, which found broad support among liberal Protestants. Intended for twelve-to-fourteen-year-olds, About Your Sexuality taught that sexuality was natural. Program facilitators led conversations about “Lovemaking, Birth Control and Abortion, Same Sex Friendships, Masturbation” and a range of other topics. Morris assailed her local and state Planned Parenthood offices for distributing sexual health and education materials that, she said, taught that “if it feels good, do it.” As another Montana woman explained, rather than teaching birth control, schools should seek to “cut down the rate of irresponsible intercourse.” Morris maintained that Planned Parenthood promoted sex outside of marriage and contributed to the rising rate of teen pregnancy.27

Heterosexual hedonism, Morris and others argued, was but one piece of a broader decline in sexual morality that included the new visibility of homosexuality. She echoed the anti-gay critique made by Phyllis Schlafly, a Catholic firebrand and political operative. From her home in St. Louis, Schlafly produced a widely circulated newsletter, the Phyllis Schlafly Report, which promoted her pet causes of anti-communism and opposition to women’s equal rights. In The Power of the Positive Woman (1977), Schlafly attacked NOW for stripping men and women of their distinct gender roles and transforming them into homosexuals. (In fact, NOW had not initially welcomed lesbians into its membership; in 1969, NOW’s president, Betty Friedan, disparaged lesbians as the “lavender menace” whose visibility might torpedo the feminist movement’s chances of success. Lesbian feminists successfully demanded that NOW represent their interests, whatever the cost to the organization’s public image.)28

Schlafly insisted that sex equality would lead lesbians and gay men to demand “special rights,” a phrase that she and other social conservatives increasingly applied to efforts to achieve equal rights: “NOW is for prolesbian legislation giving perverts the same legal rights as husbands and wives—such as the rights to get marriage licenses, to file joint income tax returns, and to adopt children,” she wrote. Women would find fulfillment, Schlafly argued, only when they embraced their unique reproductive capacities. (The mother of five children herself, Schlafly benefitted from both paid and unpaid childcare and housekeeping assistance; she was unsalaried but put in long days writing and organizing.) Morris similarly complained that Planned Parenthood, “teaches people to be gay, perverted . . . to be promiscuous. It teaches everything but the sanctity of sex.” Social conservatives like Schlafly and Morris portrayed secular sex education curricula as dangerously libidinous indoctrination.29

Sexual conservatism was the bridge that linked evangelical Protestants and Catholics across deep waters of theological and cultural difference. (It would ultimately also bring Mormon women into conservative politics.) In 1961, the evangelical megastar preacher Billy Graham answered a question in his newspaper advice column from a young woman who confessed, “through a young and foolish sin, I had an abortion. . . . How can I ever know forgiveness?” Graham responded by describing abortion as “violent” and “a sin against God, nature, and one’s self,” and urged the young woman to pray for God’s forgiveness. Evangelicals did not yet equate abortion with murder, though. In 1970, the evangelical magazine Christianity Today denounced the “War on the Womb” and campaigned against abortion reform, but no single position on abortion had yet cohered among conservative Christians.30

Instead, Protestants teamed up with Catholics to oppose pornography and stop comprehensive sex education in public schools. Thousands of evangelical Protestant women joined Schlafly’s campaign against the ERA in the early 1970s. It was through these organized protests against feminism, gay rights, and sexual liberation that many evangelical women became anti-abortion activists. By mid-decade, leading evangelical theologians and organizers unambiguously described abortion as evil. While Protestant men took over as leaders of national “pro-life” groups, evangelical Protestant women were the movement’s fiercest and most effective organizers at the grassroots level, just as Catholic women had been for years.31

Descriptions of abortion as the violent murder of innocent babies—descriptions often accompanied by graphic photographs of fetal remains—aroused the fury of activists who decided to stop abortion by any means necessary. Women like Suzanne Pennypacker Morris did not instigate firebombing, arson, bomb threats, clinic invasions, death threats, or assaults of abortion providers. They did, however, construct a narrative in which abortion providers were callous criminals, plying their obscene trade with the government’s consent. That narrative empowered some radical extremists to retaliate.32

In 1984, when Patrick’s job brought his family back to Washington, DC, Morris resigned her leadership position in Montana RTL. She does not appear to have assumed a comparable role in the nation’s capital. Five years later, Suzanne was featured in a “Where Are They Now?” roundup in the local Missoula newspaper. She and her teenage daughters had recently returned to Missoula without Patrick; the marriage had ended. Six months after she relocated to Missoula, perhaps seeking a new start after her divorce, she had her name legally changed back to Suzanne Pennypacker.33

The employees and clients of the Blue Mountain Clinic had, in the meantime, faced unprecedented threats. An especially relentless group, Operation Rescue (OR), founded in 1987 by a previously obscure zealot named Randall Terry, protested outside the clinic every Saturday. Anti-abortion activists had first launched what they called “rescues” in 1977: women activists would secretively enter and hide within clinics, barricade the doors, and then storm through the facility, destroying equipment and records. By 1985, thirty clinics had been bombed or set on fire.34

Willa Craig, who served as the executive director for the Blue Mountain Clinic during the late 1980s and early 1990s, recalled that OR activists “would stand in front of that person and try to get in the way of her actually entering the clinic.” On a few occasions, OR activists blocked the clinic’s doors. While OR attracted both Catholic and Protestant participants, Terry was an evangelical. Craig and other abortion providers began to describe their opponents as “fundamentalist” Christians.35

Blue Mountain trained a cohort of volunteer escorts, who created pathways for patients to walk in and out of the clinic and to their cars. Local police often arrested protesters who were trespassing or physically harassing patients, but the protesters returned to the picket lines as soon as they were able. Over 60,000 people were arrested at OR events across the United States. Many clinics suffered financially, if they managed to stay open at all, because potential clients were afraid to face a hostile gauntlet.36

Harassment of the Blue Mountain Clinic escalated. In November 1991, seventy-five anti-abortion protesters swarmed the building. Some used bicycle locks to chain themselves to one another’s necks. Others waved Bibles. Protesters threw their bodies against the doors and heckled patients trying to enter the clinic. A man and a woman pretending to be patients succeeded in having clinic employees bring them to the back entrance, which the couple then tried to hold open so that other protesters could get inside. Those protesters trampled several clinic workers who tried to stop them. Missoula firefighters and police responded quickly. They read aloud from a court order that prohibited protesters from blocking the clinic’s entrance, cut bicycle locks off a dozen necks, and corralled violent extremists into a school bus and a van, which took them to a holding cell at city hall.37

Supporters of abortion access turned to the government for help. A class-action lawsuit brought by NOW convinced federal prosecutors that Operation Rescue had violated the 1970 Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization Act, better-known by its acronym, RICO, which prohibited coordinated efforts to interfere with legitimate business operations. Appellate courts upheld RICO convictions against anti-abortion organizations and leaders, prompting most of those groups to distance themselves officially from violence at clinics. Operation Rescue was soon more or less defunct.38

Individual fanatics nevertheless continued to harass and threaten physicians and other clinic employees. In 1993, during the three months prior to the fire at the Blue Mountain Clinic, anti-abortion extremists threatened to kill at least thirty-one abortion providers. On March 10 of that year, an anti-abortion activist murdered Dr. David Gunn as he entered a clinic in Pensacola, Florida. It was the first, but not the last, murder of an abortion provider in the United States. Jane Snyder, the office manager at the Blue Mountain Clinic at the time, saw trouble on the horizon. Abortions represented just 20 percent of the clinic’s services by 1993. Yet to abortion opponents, that procedure defined the clinic’s existence. “I think the violence will pick up,” Snyder worried.39

Rain was falling in Missoula in the cold predawn hours of Monday, March 29, 1993, when an individual broke windows at the Blue Mountain Clinic, poured gasoline over the floors, and lit a match. That person’s movements or smoke from the flames tripped the security system. When an alert reached the fire department six minutes later, it was already too late. As the firefighters’ trucks pulled out of stations several blocks away, they saw a blaze touching the sky. Flames billowed out of the clinic. Fire Chief Chuck Gibson was apologetic when he explained, “By the time our crews got here, the building was totally engulfed.” Water and soot saturated what remained of patient records, and the roof over the reception area fell in. The fire was already the third arson of an abortion clinic that year.40

Local and federal investigators immediately suspected arson. Willa Craig blamed anti-abortion activists “and some local fundamentalist Christian churches.” Local evangelical, Catholic, and RTL leaders rejected the suggestion that they had anything to do with the fire. Instead, they suggested that it was the work of “out-of-control or deranged individuals.” A Republican in the Montana legislature suggested that the clinic’s employees might have set the blaze themselves to get an insurance payout. When arson destroyed the Women’s Health Center in Boise, Idaho, two months later, its director shared Craig’s assumptions about the culprit: “Religious fanaticism is a very scary thing, and if they can get away with what they’re doing now, then what’s next?”41

Craig insisted that the attack would not stop the BMC from providing care. They rented space from a sympathetic medical practice near the site of their former building, but there was no way that the clinic could continue as before. By August 1993, the staff had been reduced from thirty-eight to eight or ten people, a fourfold reduction, and the remaining employees were unable to meet the needs of what previously had been 7,000 patients per year. Missoula’s Planned Parenthood did not provide abortion services, only referrals. An abortion provider in eastern Montana, Dr. Susan Wicklund, was receiving death threats, and the fire in Missoula intensified her dread. Fear of violence deterred many physicians from entering this line of work at all. Nearly one-fifth of the budget for a new freestanding BMC, built after two years of fundraising, went toward a fence that encircled the building and parking lot, security cameras, and other precautionary measures.42

Clinics across the nation soon received some additional support. The 1994 Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances (FACE) Act made it a federal crime to create barriers at the entrance to a clinic or otherwise interfere in a clinic’s normal operations. President Bill Clinton’s attorney general, Janet Reno, additionally authorized the FBI to investigate some clinic arsons and designated federal marshals to provide protection to clinics after an anti-abortion extremist murdered two more physicians in 1994. Within five years, fewer than one-quarter of U.S clinics reported incidents of violence, compared to one-half of all clinics in 1994.43

Abortion providers remained vulnerable to vigilantism. In October 1994, a fire caused structural damage to the roof of the clinic where Dr. James Armstrong worked in Kalispell, Montana; he was the community’s only abortion provider. The suspect was a man named Richard Andrews, who led an Operation Rescue group in Washington state during the 1980s. By 1997 Andrews had also been indicted on three counts of arson against abortion clinics in California.44

Andrews initially denied all wrongdoing. His attorney, Thomas S. Olmstead, blamed a coordinated political effort by “powerful . . . vindictive” abortion rights supporters, who targeted Andrews and other pro-life activists to win support for their cause. For Olmstead, the campaign to normalize abortion was insidious because it diverted attention from that movement’s ultimate goal: consequence-free nonreproductive, nonmarital sex that elevated the rights of gay people and, he argued, oppressed heterosexuals. “[Pro-choice forces] are mostly feminists, lesbians,” he explained, “and they don’t want to see the product of a normal relationship between a man and a woman, which is a child.” Phyllis Schlafly and Suzanne Pennypacker Morris had made much the same argument in the 1970s.45

Federal investigators eventually collected so much evidence that Andrews confessed. In February 1998, in a federal court room where the judge described Andrews as a “terrorist,” Andrews pleaded guilty to eight counts of arson at clinics in Montana, California, Idaho, and Wyoming, the Blue Mountain Clinic among them. He was sentenced to eighty-one months in prison.46

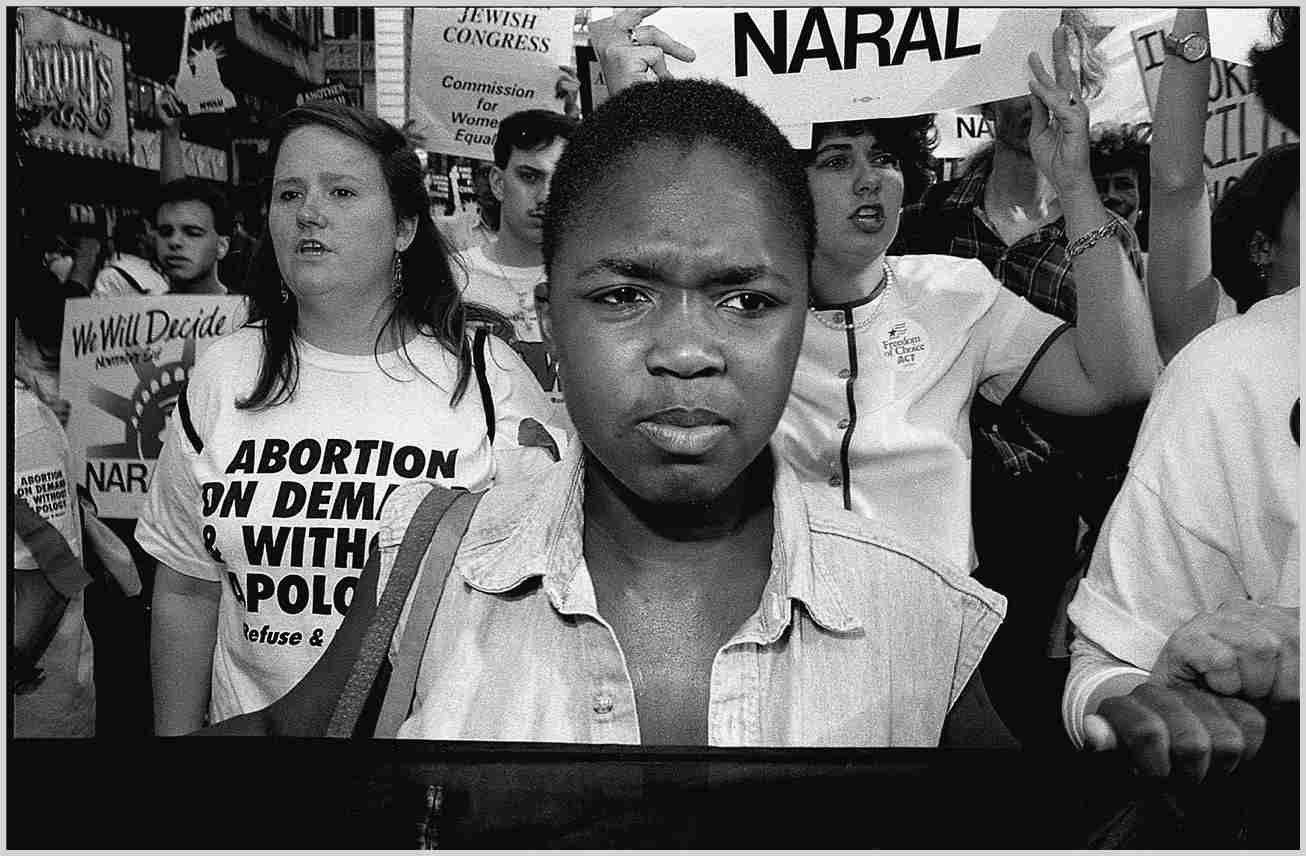

Pro-choice activists took to the streets in cities across the United States in 1992 as the Supreme Court deliberated in Planned Parenthood v. Casey. The decision ultimately upheld the constitutional right to an abortion but permitted states to impose new restrictions.

Legal remedies failed to deter radicals who believed they were on a hero’s mission to save innocent babies from murder. In 2007, anti-abortion activists in Wichita, Kansas, began to attend the Lutheran church that abortion provider Dr. George Tiller and his wife had joined. They sent postcards with images of dismembered fetuses to everyone in the church’s directory. On Sunday, May 31, 2009, one of those activists, Scott Roeder, fatally shot Tiller in the head in the church foyer.47

A protective fence encircled the rebuilt Blue Mountain Clinic in June 2022 when the Supreme Court issued its decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health. In the majority opinion, Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito issued a sweeping (and scathing) indictment of abortion and explicitly overturned Roe. Leaving the terms of legal abortion entirely to the states, Dobbs put abortion-seekers in limbo. The Blue Mountain Clinic stayed open because Montana, unlike many other states, did not have a “trigger law” ready to ban abortion the moment Roe was overturned. While legal access to abortion in Montana remained imperiled, it was something of a haven, relatively speaking. Abortion rights supporters helped Idaho residents journey to Montana for the medical care now outlawed in their state.48

Suzanne Pennypacker did not live to see Roe’s fall, having died in 2006 at the age of sixty-two. Her final letter to the editor appeared in 1994 in a dispute not over abortion but regarding her pet Dobermans. A neighboring woman had complained that Pennypacker allowed her three large and aggressive dogs to roam off-leash. One of the dogs had jumped on her several times, and all were a menace to the neighborhood, the neighbor claimed. Pennypacker called the woman a weakling who should simply spray the dogs with a little water if they got too close. She offered no apologies.49