Chapter 17

Family’s Value

When the federal government failed to address the rising toll of HIV/AIDS, protestors organized dramatic expressions of anger, grief, and resolve. Public funerals were one way of drawing attention to the epidemic’s devastating impact.

Anthony R. G. Hardaway felt called to help HIV-positive, “same-gender-loving” (SGL) Black men. (“SGL” is a preferred designation among some Black men who connect with other Black men but who do not identify as “gay” or “queer” because they associate those identities with white people, a subject this chapter explores.) Spirit-filled and outgoing, Hardaway modeled his attire on expressions of Black elegance that he encountered in church. But he was moved as well by the sorrow that soaked the ground he walked on. “He feels a part of himself is buried” with each community member lost to HIV/AIDS, a reporter explained in 2004, “and thinks it is not normal that gay men his age, 34, should feel such hurt, pain, fear and numbness to death.” More than 581,000 Americans were diagnosed with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), the cluster of diseases caused by HIV infection, between 1980 and 1996; approximately 362,000 of those people died, a horrific 62 percent mortality rate. Lower-income and nonwhite people perished with the most alarming frequency. Even after antiretroviral therapies introduced in the mid-1990s extended the life expectancies of many people with AIDS, HIV-positive Black men remained three times more likely to die than HIV-positive white men. Rates for HIV-positive Black women were comparably dire.1

Among countless acts of resistance to the epidemic, Hardaway forged a family-like community of Black men who celebrated their collective beauty. Starting in the late 1990s, he led the Memphis chapter of Brothers United in Support, an education-oriented community group for Black SGL men. (It also served, Hardaway noted, as an alternative gathering spot to the only Memphis club that welcomed queer Black people.) His efforts contributed to an international movement in response to HIV/AIDS. In Philadelphia, Kiyoshi Kuromiya cofounded that city’s branch of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) in the 1980s, created an internet communications platform for HIV/AIDS treatment information in the 1990s, and shaped the agendas of health policy organizations as an openly gay and HIV-positive person of color. Activists invented new forms of protest to save and improve as many lives as they could. A “people with AIDS” (PWA) movement coalesced in the early 1980s that championed self-love, community engagement, and safer sex. In 1983, PWA activists distributed the first-ever safer-sex manual, “How to Have Sex in an Epidemic: One Approach” and then stormed a medical conference on AIDS to present their demands for an end to medical homophobia. Community members ran errands and cared for the pets of the chronically ill, celebrities fundraised for medical research foundations, and advocacy organizations lobbied elected officials. They channeled their collective fury and grief into transforming healthcare systems, advocating for what was now more often abbreviated as “GLBT” or “LGBT” rights. Hardaway was born about twenty-five years after Kiyoshi Kuromiya, but both of their stories remind us that while we might think of HIV/AIDS as a story that ended in the 1990s, for many people, and people of color in particular, the epidemic continues and remains a threat.2

HIV/AIDS also accelerated a reimagining of what it meant to be a family. A 2001 “Family Album” of the Memphis chapter of Brothers United included a photograph of two men embracing and depicted several members wearing elaborate drag, each image in its own way evidence of the love, acceptance, and joy that the group fostered. Such a vision of family was more than affectionate: it was a political statement about a community’s survival.3

Hardaway was in his early teens when reports began to circulate of young men falling suddenly and gravely ill. In June 1981, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC)’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly reported five cases of a rare illness, pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, among previously healthy young men, “all active homosexuals,” in Los Angeles. Two of the men had died. A month later, an article in the New York Times described the appearance in New York and California of a “rare and often rapidly fatal” cancer called Karposi’s sarcoma among “41 homosexuals.” Eight of those men had died.4

No one knew at first why or how previously healthy and often quite young people were getting sick. Already by 1979, young gay men in New York and California were terminally ill with diseases uncommon in otherwise healthy younger people. Hospital workers in New York began to refer to the “wrath of God syndrome” (WOGS). Some “bewildered” physicians concluded that male homosexuality was the common denominator in the problematically named condition, “gay-related immune deficiency” (GRID). Once it became obvious that people who did not engage in queer male sex were also getting sick, medical professionals in 1982 adopted the now-standard name for AIDS. Scientists in 1984 identified a novel retrovirus that destroyed previously healthy immune systems as the culprit. Two years later, the international medical community agreed to call it the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Spread through semen, vaginal mucus, and blood, HIV attacks the immune systems of infected people of all ages and genders. Behaviors such as unprotected sex or intravenous drug use, and medical experiences such as a blood plasma transfusion, are the conduits of HIV transmission.5

HIV/AIDS was falsely termed the “gay plague,” but communities with large concentrations of gay and SGL men were initially the hardest hit. During and after World War II, large numbers of LGBT people had relocated to San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago, Miami, Boston, Philadelphia, New York, and other cities because they wanted to live among other LGBT people—to find more gay and lesbian bars, social networks, lovers, and organizations. Those same residential concentrations abetted the spread of HIV. Gay men and lesbians living through the HIV/AIDS epidemic in its early years recalled spending every weekend at funerals. “I began to live in this world where you got to know people, and you got to love them, and you laughed with them and found out how beautiful they were, and they were going to die,” one lesbian activist recalled. “In some cases you watched them fucking die . . . In sort of a naive way, it’s like, ‘You’ve got to be kidding.’ ” Lesbians and gay men had not always agreed about the priorities or internal dynamics of queer activism, but the exigencies of HIV/AIDS created a new sense of common purpose.6

Gay health clinics established in the 1970s became vital resources. Like the women’s health movement, the LGBT healthcare movement centered the patient’s experience. Clinicians focused not only on disease treatment and prevention but on a more holistic understanding of sexual health. In the early 1980s, clinics provided compassionate care for HIV-positive patients, but they did so in the absence of any viable treatments. The data about HIV/AIDS that they collected and shared with other medical centers was nonetheless invaluable.7

Larry Kramer, a white gay writer who lived in New York City, founded the Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC) in New York City in the summer of 1982. GHMC connected volunteers, affectionately called “buddies,” with seriously ill gay men and their loved ones to ensure that their needs were met. Buddies delivered meals, fetched prescriptions, cleaned apartments, or simply offered a hand to hold. Lawyers volunteering with GMHC donated their time to prevent the evictions of men too sick to earn rent money. PWAs and their partners attended group therapy sessions or called in to the twenty-four-hour crisis hotline staffed by GMHC volunteers. Similar organizations soon operated in Los Angeles and San Francisco, including Gay and Lesbian Latinos Unidos (GLLU), which advocated for gay men and lesbians within the Latino community.8

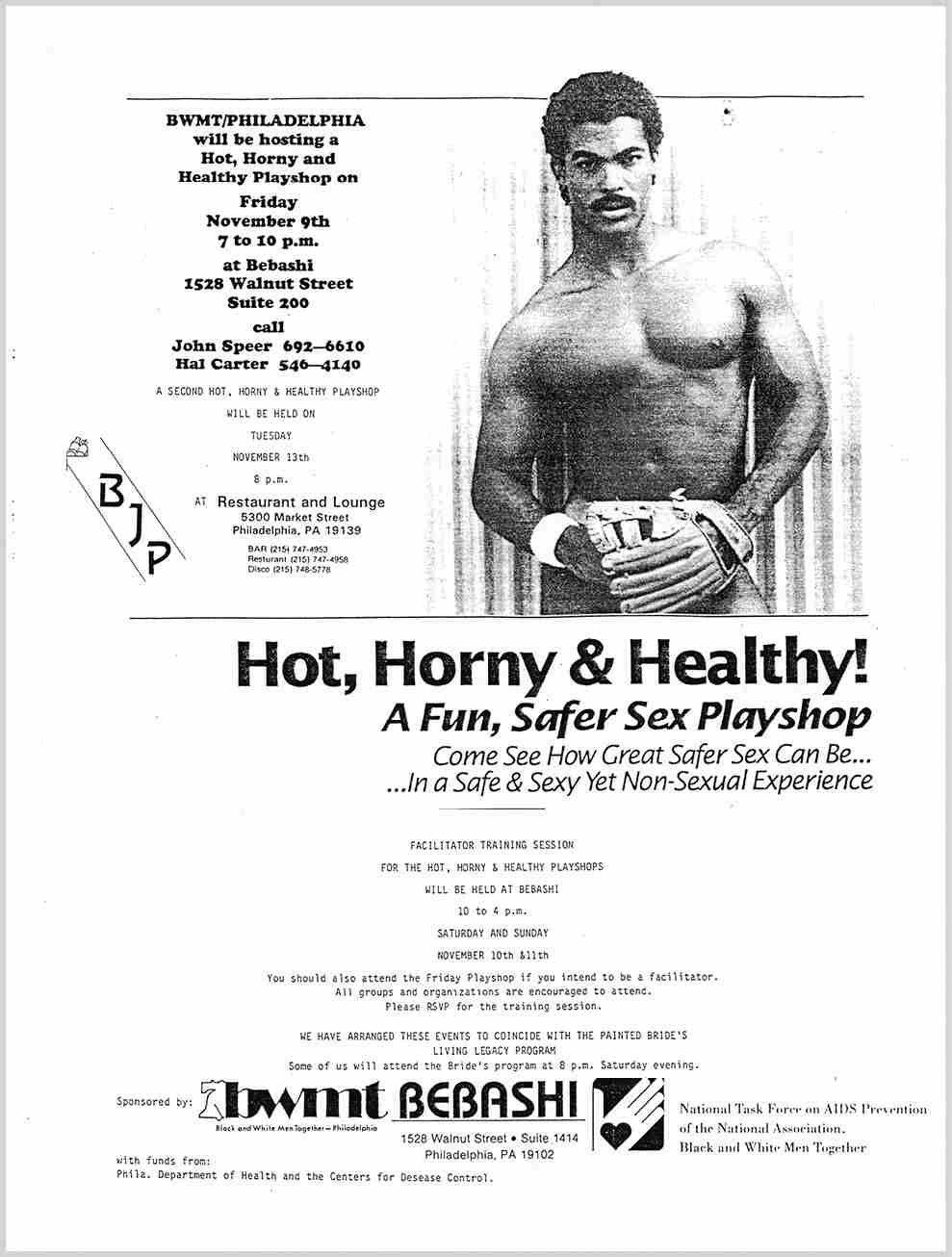

Safer-sex workshops—or “playshops,” as one group called them—were considered a crucial means of public health outreach and education, but they also affirmed the desires of HIV-positive people. One of the most popular was the “Hot, Horny and Healthy!” playshop. It originated as a project of white men who volunteered at GMHC in 1985 and was later adapted by the National Task Force on AIDS Prevention for Black, Latino, Asian-American, and Native American gay men. The playshop included discussions about sex before and during the AIDS epidemic, erotic play, condom use, and role-playing exercises. This sex-positive approach to HIV/AIDS urged gay men to change their behaviors while avoiding calls from Larry Kramer and other LGBT advocates to blame bathhouses and “promiscuity” for the suffering of gay male PWAs.9

In the rush to bring education and assistance to reeling communities, some advocates overlooked the racial divides that marked nearly all aspects of American life. A predominantly white gay organization might develop an HIV/AIDS prevention program for bars, clubs, and bathhouses where white, gay men were most likely to congregate. Yet as Kuromiya had observed since the 1970s, many of these hangouts either excluded people of color or treated them with sufficient hostility that they felt unwelcome. This discrimination occasionally included a policy against queer women. Locals in Greensboro, North Carolina, in the 1970s knew that one gay bar had a tacit policy of “no dykes and no blacks allowed.”10

Safer-sex workshops were key aspects of the response to HIV/AIDS. The “Hot, Horny, and Healthy” program was tailored to address the concerns of HIV-positive Black men, encouraging them to seek pleasure while protecting their own and their partners’ health.

Adding to this problem, many Black men saw HIV/AIDS as a primarily white, gay disease and considered AIDS service organizations to be tools of a racist healthcare system. In language that echoed some Black nationalists’ critique of “family planning” and contraception, they suspected that HIV/AIDS was a white conspiracy to rid the Earth of Black people. The scientific theory that HIV originated in Africa further alienated many Americans of African descent, who rejected that idea as the product of anti-Black animus. Native Americans were similarly suspicious about a “white man’s disease,” a skepticism based on centuries of medical abuse. That combination of inequitable medical care and cultural antagonism contributed to devastatingly high rates of infection. In 1992, the rate of infection among Native Americans was ten times the rate for Black or Latinx people.11

The Reagan administration and its conservative religious allies abetted those fears by blaming HIV/AIDS on homosexuality and utterly abandoning LGBT Americans. On the floor of the U.S. Senate, Jesse Helms (R-NC) held up a copy of GMHC’s Safer Sex Comix and insisted that what appeared at first blush to be a sex-positive presentation of condom use was instead a subversive attempt to lure unsuspecting innocents into gay sexuality. He succeeded in passing the 1987 Helms Amendment, which prohibited the CDC from spending federal dollars on AIDS education or prevention materials that, the legislation explained, “promote, encourage, and condone homosexual sexual activities or the intravenous use of illegal drugs.” Helms and other anti-gay legislators and activists warned that information about the transmission of HIV between men was equivalent to an endorsement of homosexuality.12

HIV/AIDS stirred up the fervid imaginations of some religious and political conservatives. Jerry Falwell, a fundamentalist Protestant minister and leader of the Moral Majority, a national political organization of far-right Christians, argued in 1983 for the quarantine of everyone with AIDS. The president of the Christian American Family Association, Daniel Villanueva, took the idea a step further and demanded that the United States government “QUARANTINE ALL HOMOSEXUAL ESTABLISHMENTS.” Conspiracy theorist Lyndon LaRouche and his supporters put ballot measures before California voters in 1986 and 1988 that called for quarantining all “suspected AIDS carriers.” Both measures failed, as did executive and legislative efforts in Florida to incarcerate PWAs, but the idea of quarantine persisted. The U.S. government banned HIV-positive immigrants from entering the country from 1987 to 2009.13

A vast network of “family values” publications, think tanks, advocacy organizations, and political action committees blamed HIV/AIDS on feminism, sexual liberation, legal abortion, gay and lesbian rights, and no-fault divorce. Deep-pocketed organizations like Focus on the Family, the Moral Majority, and the Family Research Council portrayed homosexuality as a sign of civilization’s imminent downfall. In 1987, Falwell proclaimed that “AIDS is the lethal judgment of God on the sin of homosexuality, and it is also the judgment of God on America for endorsing this vulgar, perverted, and reprobate lifestyle.” Such cruel statements were not confined to the family values movement. The Reagan administration shaped a national response to HIV/AIDS that appeared to treat gay men as disposable.14

The Reagan administration, closely tied to the family values movement, initially failed to respond to the HIV/AIDS epidemic at all. Surgeon General C. Everett Koop recommended a public health campaign to prevent HIV transmission and was vocal about the importance of practicing safe sex, but by 1987 the Reagan administration had done little beyond creating an “AIDS Commission” to study prevention methods. Many conservatives, including two of Reagan’s chief domestic policy advisers, Gary Bauer and William Bennett, ridiculed Koop for his views, particularly his insistence on the importance of using condoms. The Supreme Court’s majority opinion in Bowers v. Hardwick (1986), upholding a Georgia law that banned male sodomy, only reinforced the sense that the U.S. government considered homosexuality immoral and threatening.15

That antigay bias prevented the federal government from allocating resources to lessen the suffering of PWAs. In 1987, outraged and grief-stricken activists in New York City called a meeting that ultimately led to the creation of ACT UP—the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power. The radical, leaderless organization became one of the most effective single-issue pressure groups in U.S. history. Through direct actions, members of ACT UP demanded that the federal government appropriate millions of dollars for HIV/AIDS treatment and prevention research, lower the cost of medications, and loosen the criteria for drug-trial participation. Even radicals like Kiyoshi, who had spent decades protesting the incursions of state power into intimate life, now called upon the federal government for help.

ACT UP Philadelphia, which Kiyoshi Kuromiya helped establish, emphasized that the high price of prescription drugs—and inequitable access to treatment—were crises that transcended national borders. At this protest in 2000, demonstrators reminded presidential candidate Al Gore about their voting priorities.

ACT UP’s tactics were intentionally dramatic and disruptive. Activists stormed the stages of professional meetings, hung banners from the headquarters of the FDA, interrupted mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, staged a “die-in” on Wall Street to draw attention to the exorbitant price of potentially lifesaving drugs, and protested repeatedly at government agencies. Anger mixed with grief when activists marched coffins through the street in public funerals and even cast the ashes of AIDS victims on the White House lawn. “It’s so hard to remember what it was like then, with people just getting sick and dying,” a lesbian and ACT UP participant named Amy Bauer recalled years later. “There were no drugs available, and there was a lot of blame—blaming gay men for having the disease, for promiscuity, for anal sex.” Bauer found that ACT UP “gave people a place to be with other people who were as angry as they were.” That anger fueled ACT UP’s incessant efforts to save the lives of PWAs.16

It was a style of protest that Kiyoshi Kuromiya understood well. Kuromiya had been working as an editor and a writer for about a decade when the existential crisis of HIV/AIDS became the focus of his wide-ranging attention. In ACT UP Philadelphia, he pursued the twin goals of disseminating evidence-based information about treatments and pushing for more equitable healthcare access. ACT UP Philadelphia was notable for its emphasis on the interconnections among illness, economic inequality, global migration, and the capitalistic motives of the healthcare industry—pharmaceutical companies in particular. It was also notably interracial, far more so than other ACT UP groups. As he had when he connected the gay liberation movement in the United States to the human rights struggles of “Third World people” everywhere, Kuromiya recognized that any effort to expand healthcare access for people with HIV/AIDS must prioritize “global treatment access.” ACT UP Philadelphia approached the challenges facing people with HIV/AIDS in the United States as symptoms of a worldwide struggle against corporations that put profits over people.17

The association between HIV/AIDS and gay men, however, drew attention away from the epidemic’s prevalence among incarcerated women and sex workers. Katrina Haslip, a Black Muslim, learned that she was HIV-positive while incarcerated at Bedford Hills Correctional Facility, the updated name for the same institution that had housed Mabel Hampton fifty years earlier. As she educated other HIV-positive women at Bedford Hills about available treatments, she learned that the federal government based its definition of AIDS on criteria gleaned from the medical records of HIV-positive men. As a result, the definition excluded illnesses specific to female bodies, which prevented many extremely ill people from qualifying for healthcare and other services designated for people with AIDS. Compounding the problem, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had excluded women from HIV/AIDS clinical trials based on their potential for pregnancy, which meant that healthcare providers lacked any data about the appropriate dosages of experimental medications for female-bodied people, not to mention the potential side effects. After her release from Bedford, Haslip testified about the government’s failure to acknowledge HIV-positive women’s suffering. In response to a 1991 lawsuit, federal agencies expanded the definition of AIDS to include additional symptomatic illnesses. Haslip died in December 1992, at the age of thirty-three, shortly before the FDA speeded up the protocols for drug trials in cases of fatal illness and opened clinical trials to women.18

Anthony Hardaway’s efforts within Brothers United in Support reflected a somewhat different activist tradition, one that connected Black SGL people’s survival not only to medical and legal resources but to pride in their culture. Gay Men of African Descent (GMAD) in New York City, established in 1986, was among the first groups for Black gay men. GMAD and Brothers United filled a critical void left by established Black institutions, which initially directed few resources toward PWAs, and by the exclusions of majority-white gay service organizations. Brothers United’s programs emphasized the multiple risk factors in Black men’s lives: low self-esteem, inadequate access to healthcare, entrenched homophobia within Black churches in the United States and sub-Saharan Africa, and economic inequality. Those circumstances compounded the threat that HIV/AIDS posed to Black men. A breakthrough antiretroviral therapy discovered in 1996 suppressed the presence of HIV in many patients’ bodies, allowing their immune systems to function once again (some dubbed it a “Lazarus effect”), but Hardaway knew that isolated or despondent SGL men might never know about or seek medical care.19

Hardaway believed that Black literature and art, combined with public health outreach, could improve Black SGL men’s sense of pride and thus encourage them to take better care of themselves and their partners. He was inspired by an outpouring of anthologies, zines, essays, poetry, and theatrical productions by queer Black people in the 1980s and 1990s. (Essays and poetry that Black lesbian feminists published in the 1970s provided a model for much of this queer-of-color creative work.) Brothers United in Memphis sponsored a raft of events devoted to Black writers and artists. Art provided opportunities for connection. The Memphis group also hosted a support group and safer-sex workshops.20

“It was an extended family,” Hardaway commented after a weekend retreat with Brothers United of Tennessee in the early 2000s. “(It was a time) for all of us to come to one arena to encourage each other, as well as to support one another.” In his call for familial love, Hardaway and other HIV/AIDS activists invoked not the nuclear patriarchal ideal championed by “family values” conservatives nor the marital equality that would soon preoccupy centrist LGBTQ activism. He instead called upon long-standing traditions, among Black and queer people, of fictive kin, found family, and expansive networks of caring.21

Just what it was that made people family to one another had engaged the imaginations of LGBTQ people for decades. For some, the normative family and its associated sex roles were antithetical to gay liberation. “Homosexuals have burst their chains and abandoned their closets,” Kuromiya declared in 1970 in the Philadelphia Free Press, an alternative newspaper. “We came to challenge the incredible hypocrisy of your serial monogamy, your oppressive sexual role-playing, your nuclear family, your Protestant ethic, apple pie and Mother.” Feminist theorist Shulamith Firestone shared Kuromiya’s disdain for the patriarchal nuclear family. In The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution (1970), she argued that sex roles created pathological forms of heterosexuality and homosexuality that merely reproduced the power imbalances of the patriarchal family. Only the complete eradication of “sex roles,” Firestone added, offered hope for liberation. Radical activist Carl Wittman’s widely circulated essay, “A Gay Manifesto,” envisioned the creation of communes and the dismantling of the traditional family.22

One alternative to the normative heterosexual family was queer kinship, comprised of fluid yet intentional networks of “found” or chosen family members that defied legal or biological definitions. Anthropologist Kath Weston, who studied queer kinship among gay men and lesbians in the San Francisco area in the 1980s, noted that biological and adoptive relatives did not automatically merit inclusion in this kinship network. A lesbian might consider her birth or adoptive parents her family only if they accepted her sexuality and welcomed her lover into their home. Queer kinship was premised on actions: the people who accepted you and showed up for you—emotionally and materially—were your family. For queer people whose biological or adoptive parents had disowned or otherwise rejected them, chosen family filled a void.23

Chosen family became a crucial lifeline as HIV/AIDS transformed previously healthy young people into critically ill patients with complex healthcare needs more often associated with the elderly. Queer kin sat at hospital bedsides, checked in with an ailing patient’s doctors, and memorialized the dead. As the next chapter explores, such caregiving was one facet of a larger effort by LGBT advocates to protect the custody rights of lesbian and gay parents and formalize the legal relationships between same-sex partners.

An AIDS diagnosis was often how biological family members learned that a child or sibling was gay, using intravenous drugs, or having sex with HIV-infected people. Parents might hide the truth about their child’s illness, telling neighbors (and writing in obituaries) that their child had died from cancer or another disease. Others became advocates for PWAs and allies of the LGBTQ community, such as one Jewish mother who left her synagogue after the president of the congregation treated her son’s gay identity as something shameful. Many parents, and especially mothers, became the primary caregivers for their ailing adult children.24

Hardaway wanted young SGL Black men to experience love and affirmation. Even while in his early thirties, often going by his nickname “Ladybug,” he surrounded himself with “the children,” younger people for whom he was more than a mentor; he was family. As a friend observed, “People see God in Anthony. He touches them.” Survival depended on healthcare, housing, and other material assistance; Hardaway insisted that SGL Black men such as himself also needed to have their souls and spirits uplifted.25

Hardaway grew up singing in his church choir, a space filled with gender-nonconforming men but also significant hostility toward homosexuality. “I heard what other church people said,” he recalled. “ ‘It’s a shame all them sissies in the church,’ but it wasn’t directed toward me. I never heard the word ‘gay’ in church, or ‘homosexual’; it was always ‘sissy.’ ” None of those experiences offered Hardaway a positive role model. “Nobody wanted to be gay,” he added. “My parents didn’t want a gay child . . . You were lower than the devil if you were gay in the church. You could be the biggest ho in the church and get respect. [But not] being gay.” Gay men and lesbians participated in their churches only by masking or silencing their desires. Rev. Renee McCoy, who led the gay Harlem Metropolitan Community Church, explained, “If Black lesbians and gay men are willing to check their sexuality at the door of the church, and come bearing gifts of talent, there are relatively few problems.”26

Yet within those silences, many queer people sang in their congregations’ choirs, fooled around with same-sex partners in church basements, and otherwise participated in a religious community. Particularly in parts of the South and within subcultures where the church dominated much of the community’s social life and politics, the adaptations were manifold. Hardaway gradually came out by inviting his family members to events with gay themes; they took the hint.27

The Black church’s culture of silence around homosexuality did not diminish Hardaway’s faith, but he knew that he needed to protect his reputation—even in death. “I don’t want a funeral,” Hardaway noted in the early 2000s. “I want to be taken straight to my grave. I can’t stand the lies. If you really want to honor what I’ve done, teach someone who’s black and gay. Teach them about their history. That’s how you eulogize me.” Hardaway’s concern about how to eulogize the dying—how to mourn—has preoccupied generations of people affected by HIV/AIDS. The hostility of many major U.S. religious organizations, particularly the Roman Catholic Church and many evangelical Protestant congregations, pushed some people out of organized religious life while ushering others into alternative spaces for spiritual community.28

Gay- and lesbian-friendly churches and synagogues, the first of which opened during the 1970s, meanwhile became havens for PWAs and their loved ones. Parents and lovers who had been excluded from mourning rituals within anti-gay religious spaces (Orthodox Judaism, many Roman Catholic parishes, and much of evangelical Protestantism) sought out queer-friendly congregations. In the years before domestic partnership laws, not to mention marriage equality, these religious groups recognized bonds among same-sex friends and lovers that the state did not. AIDS thrust these congregations to the front lines of the epidemic. Half of the men active in New York City’s Congregation Beit Simchat Torah, the first gay and lesbian synagogue in the United States, died during the early 1980s. The nondenominational, gay-friendly Metropolitan Community Church of San Francisco similarly watched as AIDS devastated its community. Over the ensuing decades, mainstream religious organizations with more liberal philosophies became accepting of LGBTQ people, but culturally conservative religions remain hostile spaces for many queer people.29

Kiyoshi Kuromiya was diagnosed with AIDS in 1989. At one point, his T-cell count, which hovers around 1,000 per cubic millimeter of blood in a healthy person, dropped to 36, leaving him dangerously vulnerable to infections. He took AZT, a drug with noxious side effects, to raise that count to 53. All told, he took nearly thirty pills a day. Kuromiya was determined to live “25 years with a T-cell count in the single figures,” but his appetite and strength declined.30

Kiyoshi Kuromiya devoted the last fifteen years of his life to healthcare activism on behalf of PWAs. Here, he joins other members of ACT UP Philadelphia in opposing mandatory HIV testing programs and urging comprehensive safer sex awareness instead.

In addition to his work with ACT UP, Kuromiya created the Critical Path Project, an initiative to get free internet access to people with HIV/AIDS and to circulate the latest information about new drugs and clinical trials. Spending hours at his computer in his cramped apartment, Kuromiya connected patients with advocates, caregivers, researchers, and policymakers. He ran a hotline and published a newsletter. By 1994, he even ran a small buyers’ club, “Transcendental Medication,” providing marijuana to about twenty people with AIDS and other illnesses. Kuromiya defended marijuana as an essential means of easing the nausea and appetite loss he experienced due to AIDS: “I can smoke a joint, and five minutes later, I can eat every last drop of food.” Ever the activist, in 1999 Kuromiya was a lead plaintiff in an unsuccessful case to legalize medical marijuana use.31

In early May of 2000, as Kuromiya’s mind and body reached their end, a rotation of friends kept vigil at his bedside at Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia. Several of these friends—Jeff Maskovsky, J. D. Davids, and Jane Shull—had been overseeing his care for months already as he declined. Most knew Kuromiya through activism with ACT UP or other HIV/AIDS advocacy groups. Maskovsky was completing a PhD in anthropology at Temple University about We the People, a coalition of PWAs made up almost entirely of low-income people from racial minorities. Maskovsky was not one of Kuromiya’s closest friends, but he and others undertook this incredibly difficult role out of respect and love. They scrupulously recorded Kuromiya’s vitals, pain levels, and medications in a spiral-bound notebook. One person would arrive for the night shift, relieving someone who had been there throughout the day. Emiko Kuromiya was there, too, massaging her son’s hand.32

Kuromiya briefly woke one night and “even sang a refrain of the Univ. of PA cheerleading song.” Cathy, his night nurse, gave him morphine a few minutes later, and he fell asleep. Kuromiya’s blood pressure was normal, but he was bleeding from his rectum and had a fever. He trembled occasionally. When awake, his conversation straddled delusion and reality. He held his fingers to his ears as if speaking into an imaginary phone. “I was just trying to get some information across,” he told Scott Tucker, a friend. Knowing time was precious, Tucker seized this moment of quasi-lucidity.

“Kiyoshi, I never asked you what your name means in Japanese.”

“Kiyoshi means ‘to make clear.’ ”

Tucker and other friends noted every shift in Kuromiya’s affect. The night of May 1, Kuromiya’s pain intensified. The nurse switched from morphine to Demerol. By the following morning, Kuromiya had started to vomit blood.

Maskovsky took over from Tucker a little after three a.m. on May 2. “5:30 a.m. Temp. 101.” Maskovsky kept careful notes but worried that he did not know the names of all of Kuromiya’s caregivers. “5:45 Senior Surgical Resident, Dr. Shannon Gehr—check spelling!—visits room. Heart 130.” Tucker had not yet gone home; perhaps he napped while Maskovsky took notes. By morning, Shull, the executive director of Philadelphia FIGHT, an AIDS organization, was recording Kuromiya’s condition in the notebook.

Kuromiya moved through states of being asleep, awake, and somewhere in between.

“Where should I be?” he asked Shull.

“Right here?” she offered.

“No,” he countered. “Where-should-I-be?”

“Physically?”

“Yes, I know I’m here for now, but I’m in the [San Francisco] bay area [without] a map, on foot somewhere [east] of Presidio—not sure where that is—like a desert, 5 or 20 or 30 miles from where I should be . . . People are climbing giant trees.”

“That sounds nice,” Shull said.

Pain medications allowed Kuromiya to hallucinate. “It’s amusing since otherwise I’m just laying here. Somewhere I lost my shirt and I’m not even in Reno!” His sense of humor was intact.

Another friend arrived a little after six that evening. Kuromiya’s condition was worsening. The nurse paged the doctor on call after Kuromiya had a bowel movement: “blood is just pouring out of him.” They gave him two units of platelets, and the doctor arrived. The plan, a friend explained, was “pumping blood into him as needed and monitoring blood loss.” Kuromiya woke occasionally and asked questions about his condition. His friends offered what reassurance they could. He coughed up what one friend estimated to be half a cup of blood.

“Kiyoshi sleeps,” David Acosta wrote on May 3, after Ativan eased Kuromiya’s mind. As had other friends, Acosta noted when Kuromiya was in pain and the relief that he felt after another dose of Demerol. The friends were incessantly attentive. Had the nurses given Kuromiya enough pain medicine? Were they rotating him every four hours to protect his fragile skin from tearing? When Kuromiya had episodes of labored breathing, they insisted that nurses call a resident. They questioned recommendations for certain medications that could improve breathing but risked causing cardiac distress.

By the afternoon of May 5, the doctors were “cautiously optimistic,” but that feeling was short-lived. Kuromiya was soon vomiting a mix of blood and phlegm. He was becoming increasingly delusional.

The twelve or thirteen friends who rotated shifts by Kiyoshi Kuromiya’s bedside cared for one another too—and for Emiko. “Chuck just took Mrs. K. to dinner,” one of the friends noted. “Jackie [Jacqueline Ambrosini] took Jeff home. Rita A., Judith P. [Peters] and Heshie [Zinman] here. 5:15 Demerol. Dr. Lobo—here—advises Demerol 3x hrly.”

Human touch and presence bound Kuromiya to the members of his found and natal family. “Foot massages help K feet very cold. Mom makes K smile.”

Kiyoshi Kuromiya died on May 10, 2000, the day after his fifty-seventh birthday, surrounded by family. A few friends recited Jewish and Christian prayers at his bedside. They read aloud the Buddhist Heart Sutra: “Gone, gone, gone beyond, gone altogether beyond: all hail the Awakened One!”33

Perhaps Kuromiya had experienced his vision of mapless wandering as a kind of relief, liberated from pain, time, and distance. He was shirtless yet mobile, amused by people climbing “giant trees.” He was also vulnerable, “somewhere” in the desert, exposed.

Anthony Hardaway sauntered through a 2022 Instagram reel for the Haven, a community-based testing, counseling, and referral organization in Memphis, as a three-decades (and counting) HIV/AIDS survivor. He smiled and twirled to advertise the Haven’s upcoming competition and fundraiser, the “Triple Threat Ball.” In the tradition of queer-of-color ballroom, contestants between the ages of eighteen and twenty-five competed for prizes that recognized the “realness” of their performances of dance, attire, and attitude.34

Escalating police harassment in the 1930s and 1940s shuttered most queer ballroom events, but queer performances persisted. Ebony magazine reported in 1953 on “the world’s most unusual fashion show” in Harlem, where “men who like to dress in women’s clothing parade before judges.” The article mocked drag, but it also testified to drag’s persistence. In the 1960s, a new circuit of gay beauty pageants created alternative spaces for drag performance and helped bring about ballroom’s renaissance.35

The 1967 “Miss All-America Camp Beauty” competition in New York City became legendary for the outraged reaction of Crystal LaBeija (Miss Manhattan) following the announcement that she was the third runner-up. Crystal, who was Black, accused the winner, a white queen from Philadelphia named Rachel Harlow, of benefitting from a “rigged” process. Crystal’s verbal evisceration of Harlow and the pageant’s organizer, memorialized in the documentary The Queen, epitomized the practice of “reading,” an artful and often vicious form of verbal insult. Another legendary ballroom mother, Dorian Corey, explained in the 1991 documentary Paris Is Burning that a person who gives a reading “found a flaw and exaggerated it.” The related art of “shade” takes the insult a step further. “Shade is, I don’t tell you you’re ugly,” Corey noted while applying her makeup at her elaborate vanity. “But, I don’t have to tell you, because you know you’re ugly.”36

Crystal LaBeija vowed never to compete in a white-run pageant again and instead cofounded the first ballroom “house,” the House of LaBeija. Other ballroom houses, often named for a fashion designer or drag icon, soon followed: House of Corey (1972), House of Dior (1974), House of Wong (1975), and House of Dupree (1975), among others. The House of Xtravaganza (1982) was the first Latinx house. By the early 1980s, houses based in Harlem and Brooklyn competed for which one could bring home the most trophies for a series of established categories, such as “femme realness,” “butch realness,” “voguing,” and “executive realness.” Ballroom houses gradually emerged in U.S. cities from Detroit to Miami to Los Angeles, with some rural and Southern communities also creating regional “scenes.”37

Familial terms suffuse the world of queer ballroom, with contestants performing on behalf of particular “houses,” each of which has a “mother” or “father,” a queer man or transwoman who looks out for their “children.” House mothers take in kids who have been kicked out of their homes or disowned because of their sexuality or gender expression; many are HIV-positive. Ballroom serves as a lifeline for young people who hustle drugs or sex to sustain themselves, and who depend on their “street families” for their survival. “If they join a house, they can belong somewhere,” a DJ who spun records at a club in the Bronx noted in 2000. Ballroom participants celebrate survival despite unfathomable loss, and they do so while giving shade, reading, and voguing, a dance that combines defiantly glamorous poses with acrobatic spins and falls.38

Too many of Hardaway’s friends died too soon, but he has held on to joy. “We were such a rarity, so powerful and magnificent, the common people don’t know how to take it,” he once boasted about queer Black people. “Anything that is so beautiful, too beautiful to be touched or expressed, we tend to destroy.” He wanted that beauty to endure. In 2019 Hardaway partnered with local LGBT organizations and faculty at the University of Memphis to establish an archive that would gather and interpret records of Memphis’s queer past. He continues to work in HIV/AIDS outreach and education, and he celebrates the beauty of queer drag and LGBTQ love.39

And really, what is the danger in that?