Chapter 5 Each of Us

Without ethical culture there is no salvation for humanity.

–– Albert Einstein1

In 2015 the Dalai Lama was in London launching a new course called ‘Exploring What Matters’. At one point a middle-aged woman came on to the stage. She was in pain and on crutches. For years she had been mostly bedridden and often depressed. But then she happened to hear about the course and enrolled locally. It changed her life. She realized that, by helping others like herself, she could give meaning to her life. The Dalai Lama embraced her. Later on, he was asked, ‘What is the most important thing for a happy life?’ Without hesitation, he replied, ‘Warm heart’.

In the end it is each of us as individuals who will determine the levels of happiness in our society – by everything we do. It is not easy to live well, but it is very much easier if you are in regular contact with people who are trying to do the same. In the West this used to happen when people went to church. They were reminded that they were not the centre of the universe: there was something bigger than them. And they were inspired, uplifted and comforted. They re-established contact with their ‘better selves’.

The moral vacuum

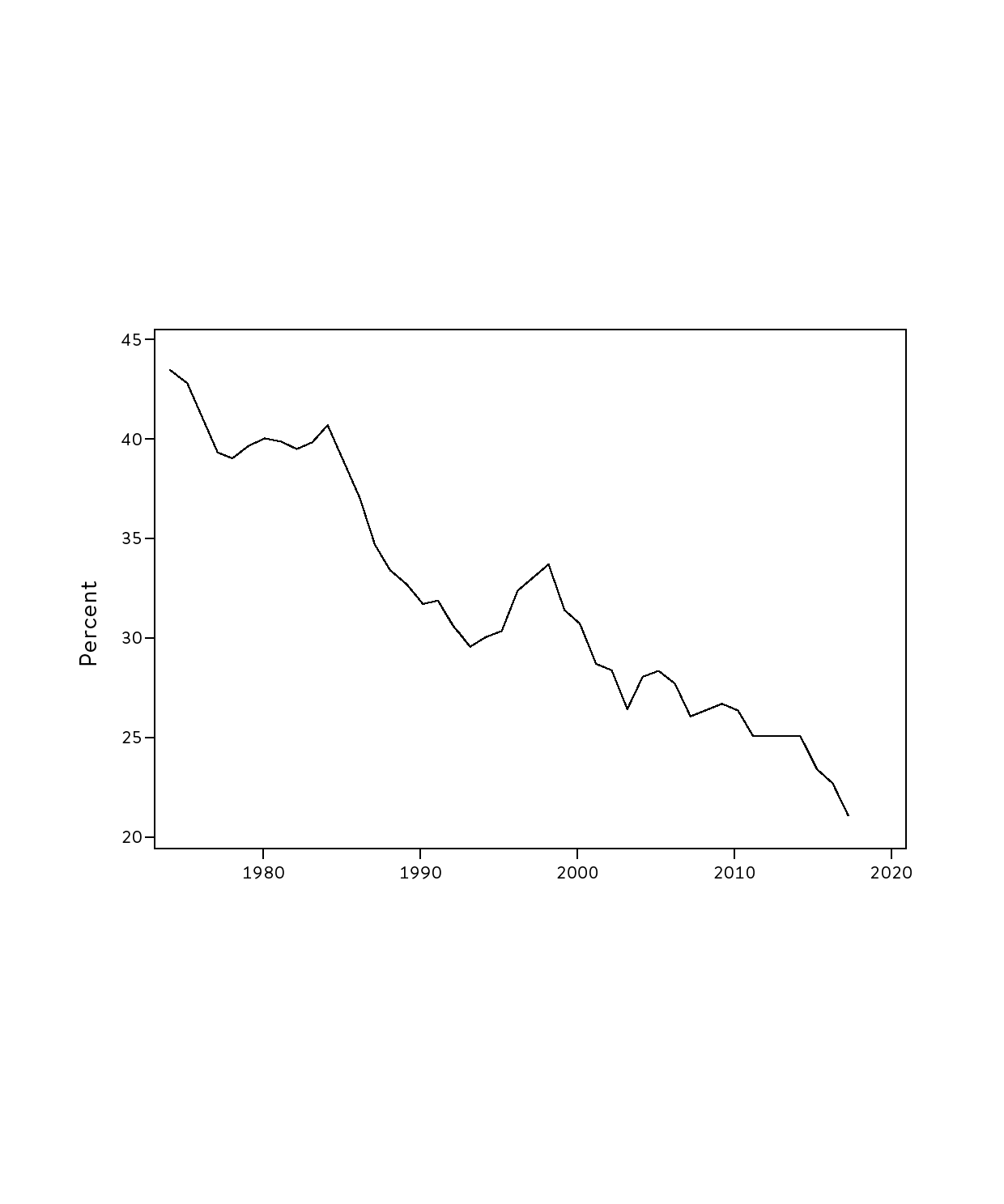

But today very few Europeans go to church, and even in the USA religion has been losing its hold (see Figure 5.1).2 This is one of the most profound changes of our age. People no longer define ethical behaviour as conforming to the will of God. To some extent the old rules of behaviour – based on religion – persist, but their hold is weakening. Back in 1952 one half of all Americans thought people led ‘as good lives – moral and honest – as they used to’. There was no majority for the view that ‘things are going to the dogs’. But by 1998 there was a three-to-one majority for precisely that view – that people are less moral than they used to be.

Clearly there has developed, to a degree, a moral vacuum into which have stepped some dreadful ideas. Many of these ideas are highly individualistic, with an excessive emphasis on competition and on personal success as the key goal in life. In that view each person’s main obligation is to themselves. An extreme proponent of this view is the writer Ayn Rand, who became the favourite guru of Alan Greenspan and later of Donald Trump.3 In her world individuals do of course collaborate on occasion, but only when it is in their own individual interest to do so. There is no concept of the common good, and life is largely a struggle for places on the ladder of success. But such a struggle is a zero-sum game, since if one person rises, another must fall. In such a world it is impossible for everyone to become happier. For that to happen, it has to be through a positive-sum game where success for one brings success for others.

So we need a new ethics that incorporates the best values to be found in all religions, but which is equally convincing to people with no religious faith at all. As the Dalai Lama has put it, ‘For all its benefits in offering moral guidance and meaning in life, religion is no longer adequate as a basis for ethics. Many people no longer follow any religion. In addition, in today’s secular and multicultural societies, any religion-based answer to the problem of our neglect of inner values could not be universal, and so would be inadequate. We need an approach to ethics that can be equally acceptable to those with religious faith and those without. We need a secular ethics.’4

Percentage saying that they had a great deal of confidence in the church or organized religion (USA)

What should it be based on? It has to be based on our Ethical Principle – that each of us should try to create the most happiness we can in the world, especially among those who are least happy. This principle has a universal appeal, to people of faith as well as those of no faith. In the language of Christians, Jews and Muslims, it embodies the commandment to love your neighbour as yourself. In the language of Buddhists, Confucians and Hindus, it encompasses the principle of compassion – that in all our dealings we should truly wish for the happiness of all of those we can affect, and that we should cultivate in ourselves an attitude of unconditional benevolence.5

This faith allows us to think of ourselves as well as others. But, since there are so many more others, it strongly encourages us to achieve our own happiness in large part by contributing to the happiness of others.

No belief system can flourish without institutions that embody it – gatherings where people can meet regularly to reinforce their commitment to live well. But there are as yet surprisingly few secular institutions which attempt to fill the void left by the retreat of religion. When I was a student at Cambridge, I was a founder member of the Cambridge Humanists and I hoped that Humanist associations worldwide would inspire people to lead good lives. But mostly they have concentrated instead on the less inspiring role of criticizing religion.

In the West the most obvious non-theistic groups that meet regularly around the central issues of life are Buddhists and mindfulness groups.6 There are also huge numbers of charitable organizations. Some have specific benevolent purposes (like Alcoholics Anonymous, the Red Cross and countless forms of volunteering). Others have wider purposes but a restricted membership. But there are very few secular organizations which can be compared with the churches, whose purpose is the whole of life and whose membership is open to all.

That is why in 2011 we founded Action for Happiness, a secular movement for a happier society. The patron is the Dalai Lama, and members make the following pledge: ‘I will try to create more happiness and less unhappiness in the world around me.’ So far, over 150,000 people from 175 countries have made that pledge – in other words they will live according to our Ethical Principle. And over a million other people are following the Action for Happiness message on Facebook, which shows the hunger that exists for these ideas.

But how in practice does Action for Happiness help people to live better and more fulfilling lives?

- First, it offers them Ten Keys to Happier Living (online and in book form).7

- Second, it offers an eight-session course on Exploring What Matters, where people can reflect on how our Ethical Principle can be applied in their lives.

- Third, it is forming thousands of groups worldwide who meet regularly to inspire each other, using standard materials which the movement provides.

Ten Keys to Happier Living

The Ten Keys are a guide to behaviour and attitudes conducive to a happy society, based on the evidence of modern psychology.8 But they also embody much of the ancient wisdom found in Buddhism, Christianity, Confucianism, Graeco-Roman philosophy, Hinduism, Islam and Judaism. In all of these traditions there is a common core of teaching about how human beings should manage their mental lives, and that is what the Ten Keys are ultimately about – the management of our mental lives.9

All ten keys are shown in Figure 5.2, and the first letters of each key spell ‘GREAT DREAM’. Those in the top section (GREAT) were first constructed in response to a question from the British government: ‘If five fruit and vegetables a day are good for your physical health, what five things each day are good for your mental health?’10 So the Daily Five are behaviours which should be undertaken at least once a day. But equally important are our ‘habits of mind’ – our basic philosophy of life. These comprise the bottom half of the figure and spell the word ‘DREAM’.

It is natural to ask how these different elements relate to each other: which, if any, has priority? I will give my own answer to that question. Underlying all of the keys is a positive frame of mind – a habit of looking for the best in a situation, and the best in another person. Without this, nothing goes well. For example, the psychologist John Gottman has shown that in happy marriages people make at least five positive comments to each other for every negative one, while in failing marriages the ratio is less than one to one.11

Ten Keys to Happier Living

Human nature includes both positive and negative strands. In early human life in the savannah the negative strand was crucial. You always had to look out for threats and dangers in the world around. If you did not, you got eaten and failed to reproduce. Today, we have far fewer threats to our survival; but we still interpret as threats things which are not. In the English language, 62 per cent of the emotions for which words exist are negative emotions.12 Negativity affects our willingness to reach out to other people and to new experiences. And it affects our response to genuine adversity. So if we want to be happy we have to consciously strengthen the positive side of ourselves. There is an old Cherokee story: an old man tells his grandson, ‘There is a fight inside you between two wolves – one is selfish and the other is loving.’ ‘But,’ says the boy, ‘which wolf will win?’ To which the old man replies, ‘The one you feed.’13

Thus a positive approach is what can help us with each of the keys. Starting with our ‘habits of mind’, positive thought obviously generates positive emotion. Gratitude exercises are strongly recommended along the lines proposed by Martin Seligman (and many ancient sages before him).14 A positive frame of mind also generates the right responses to adversity. Resilience comes from treating a setback as a challenge, and trying to accept it as such. Positive thinking also means that we accept ourselves and we accept others. We avoid constant comparisons between us and them, and we learn to forgive. Acceptance does not mean passivity – it provides the firm foundation for action. For this we need an inspiring purpose, a direction and meaning in our lives.15 So our general habit of mind should be one of compassion – both to others and to ourselves.16

This in turn affects our daily actions. So, turning to the Daily Five, the first place goes to giving. This is for two reasons: it helps the helped, and it helps the giver. As Portia put it in The Merchant of Venice when she described mercy, ‘It is twice blessed; It blesseth him that gives and him that takes.’ Next comes relating. We are deeply social animals and we are desperate to be loved and appreciated. The best way to be loved and appreciated by someone is to care for them – to help them, and make them feel better each time they see you. At the centre of any successful relationship is the heartfelt desire for the other’s wellbeing. Help that is given for the sake of a good turn in response (reciprocity) is less satisfying than help given out of the goodness of your heart (altruism). What is required in our relations with others is more than respect or toleration; it is heart-felt goodwill.

Through practice, we can increase the level of our goodwill. The leading expert on positivity, Barbara Fredrickson of the University of North Carolina, has studied the effects of Loving Kindness Meditation, otherwise known as Compassion Meditation or Mettā. In this meditation the participants cultivate good feelings in succession, first for themselves, and then for a loved one, then for an enemy and then for humankind. The results are increased positive emotion, increased flows of the feel-good hormone, oxytocin, and improved tone in the vagus nerve which controls the heart rate.17

Positivity also makes it easier to practise mindful awareness. Meditation may help some people, but many of the most mindful people have never meditated. It is a matter of living more in the present and appreciating every good aspect of your surroundings and your life. Finally, we need the habit of exploration (trying out) – both mental curiosity and physical discovery – and the habit of physical exercise, on which so much has already been written.18

There are of course serious people who question the whole concept of positive thinking. For example, in her book Smile or Die, Barbara Ehrenreich prefers ‘realistic thinking’.19 But there doesn’t need to be a conflict between being positive and being realistic. If we are to help other people, we need to be totally realistic about their situation. But when it comes to ourselves, we can choose what to focus on. If the external situation is really bad, we should try to change it. But if our life is the usual mixture of good and bad, it will be better for us (and for those around us) if we focus mainly on the good. Let’s celebrate the glass half-full.

Action for Happiness groups

How can people be helped to practise the wisdom of the Ten Keys? The wisdom is on the Action of Happiness website and in Vanessa King’s fine book on the Ten Keys. It is also reflected in the daily online calendars which are based on one Key per month and provide a helpful thought for each day.20

But almost anything really important is best done face to face with other people. That is the point of the course known as Exploring What Matters and of the Action for Happiness groups that emerge from it. Exploring What Matters is an eight-session course of two hours each week that surveys the great issues of living: what we are aiming at; what makes us happy; how we can calm our minds; how we can make others happy; how we can have good relationships at home and at work. Each course is led by two volunteers who are screened and supported from the centre. For each session a set of materials is provided and there is a standard format: a mindfulness period, followed by a video talk by an expert; then a review of scientific evidence; followed by a discussion of how this fits your experience and what action you will take as a result.

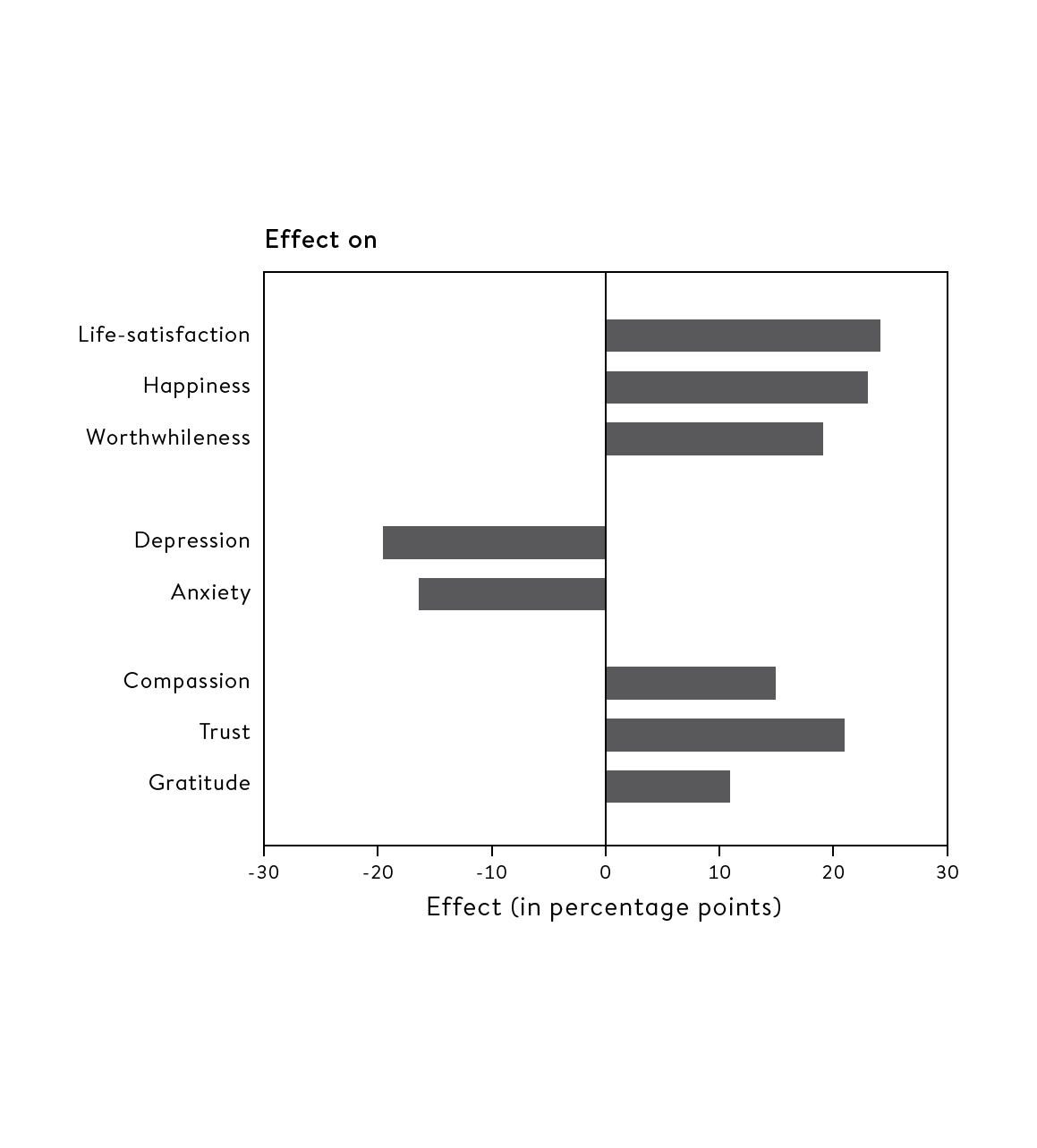

The Exploring What Matters course was launched by the Dalai Lama in London’s Lyceum Theatre in 2015. It has proved remarkably successful. By mid-2019 over 300 courses had been held in sixteen countries with 5,000 participants. In addition there has been a scientific evaluation of the effects of the course. This trial involved 146 participants, half of whom were randomly chosen to be controls on a wait-list. The results were remarkable.21 Two months after the course, people who took it were nearly a whole point higher in life-satisfaction (0–10) than if they had not taken the course. This is larger than the effect when an unemployed person gets a job – it is a big effect.

Another way of seeing the size of this effect is to ask if a person with average happiness took this course, where would she end up in the ranking of happiness? The answer is that she would probably rise from 50th place (with 100 being the highest rank) to 74th place – she would rise by 24 ‘percentage points’. This is often a very useful way of reporting the impact of a change and we shall use it frequently in this book.22 It is used in Figure 5.3 below, which also shows the dramatic effects of Exploring What Matters courses on mental health and on pro-social attitudes.

The Exploring What Matters course has big effects (two months later)

The success of the course is due not only to its powerful content, but also to two other features. There is no fee for the course – people give what they can afford or choose to give – so it attracts a huge cross-section of people, both rich and poor (as do churches), and disproportionately large numbers of people who are either very unhappy or very happy. Secondly, all of them are there on the basis of complete equality, including the volunteer leaders of the course. When asked about the impact of the course on their lives, an average of 97 per cent said it was positive. And, once people have completed the course, they are encouraged to create a local group which meets regularly following a standard format.

Related secular movements

There are of course other secular movements which share many of the objectives of the Action for Happiness groups. Many of them only teach courses rather than meeting regularly on an ongoing basis.23 But some, like Buddhist and mindfulness groups, also meet regularly.

One movement with objectives similar to Action for Happiness is Sunday Assembly. Founded in 2013, these groups meet weekly, often with hundreds of participants. Their motto is ‘Live better; help often; wonder more’ and the theme of their meetings is celebration. Each meeting lasts roughly an hour, with a standard format including talks, singing and readings. The meetings are led by local leaders who have received an eight-session training webinar. Currently there are seventy Sunday Assemblies around the world.

Another recent movement has a particularly impressive record of growth: the Art of Living Foundation. This movement for harmonious and ethical living was founded in 1981 by Sri Sri Ravi Shankar, a wise Indian guru with a wonderful twinkle in his eyes.24 The centrepiece of his teaching is the Happiness Course, which teaches a strenuous form of breathing. He also has his own version of meditation which is a modified version of TM, where the mind rests rather than concentrates. These two practices are the central features of group meetings of the Art of Living Foundation. The movement now has 10,000 groups worldwide. Unlike Action for Happiness, it is led by trained teachers, while Action for Happiness prefers volunteers, because this establishes an amazing atmosphere of equality and sharing during a meeting, which can be very uplifting.

The oldest movement of all is the humanist movement or the closely related ethical societies that exist worldwide.25 They are of course the source of many of the ideas in this book, and they offer many excellent events such as lectures and humanist weddings and funerals. But they have not really satisfied the needs of millions of people to meet regularly in order to be strengthened, supported, comforted and uplifted. We need new organizations to do this.

Effective Altruism

There is one other issue for us as individuals: what should we do with our money? If we are relatively well-off, we could almost certainly do more good by giving some of our money away – that is, more good to others than the cost to us and our families.

One obvious target is poorer people in Third World countries.26 But what form should the aid take? There is a movement called Effective Altruism, which encourages people to make choices in life so as to maximize happiness all round.27 So when giving money to charity, they advise giving to organizations that produce the biggest increase in happiness-years for every dollar they receive. To facilitate this, the website of Give Well, based in San Francisco, shows how different charities compare in terms of cost-effectiveness.28 It shows, for example, that malaria and de-worming charities give excellent value for money. Another organization called 80,000 Hours urges people to choose their careers so as to create the most happiness for present and future generations.29 As that organization points out, for some people the most effective choice is to make a lot of money and then give most of it away.

Conclusions

A new culture has to be based on individuals – what we each value and how we behave.

- We need to address the moral vacuum which has been left by the retreat of religion. Where egotism has replaced it, we need instead the generous philosophy embodied in the Happiness Principle.

- To live well, we need to cultivate the positive side of our nature which can nourish us and help us reach out to others.

- For many people it will help to belong to a community of people, like Action for Happiness, who share our outlook.

Together we can build a happier society. But each of us will contribute in our own unique way. So what can people in different occupations do to make the world a happier place?