Chapter 11 Economists

The ultimate purpose of economics, of course, is to understand and promote the enhancement of well-being.

–– Ben Bernanke, former Chairman, US Federal Reserve.1

When I was twenty-seven, I was appointed as research officer for a government committee on the future of British higher education. On my very first day, as I sat at my desk, I was confronted by a paper from the Treasury. It asked, ‘Which should have the greatest priority: expanding higher education or remaking the decaying cities of the North?’ I realized I had absolutely no way of thinking about this issue; I did not even know how to begin. The result of this experience was that I became an economist.

The economic approach

I had discovered that, alone among disciplines, economics gives us a framework for choosing priorities. This framework has three elements. First, there is the thing which has to be maximized – the happiness of the people.2 Then there are the constraints – resources, technology and human nature. And, finally, there are the policy levers – regulations, spending programmes and taxes to pay for them. The challenge is to choose those policies which produce the most happiness, while satisfying the constraints. It is a brilliant framework.

The moment I heard about it I bought it. For as a history undergraduate I had read both Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill. They too believed that we should judge the state of a society by the happiness of the people, and I could imagine no better objective than that.

But the next step was trickier. What does happiness depend on? The answer most economists give is, essentially, a person’s ‘purchasing power’ – the mixture of goods, services and leisure that your wage and your unearned income enable you to buy. Since wages and profits add up to gross domestic product (or GDP), this has led to the widespread use of GDP as a measure of the happiness of the people.3

When I became an economist, I was quite shocked to discover this practice, because GDP leaves out so much that matters – in fact most of the things that we have discussed in this book.4 On top of that, it ignores the issue of who gets this money, since it treats a rich person’s dollar as of equal value to a poor person’s dollar. Happiness research shows how wrong this is: an extra dollar for a poor person produces ten times more extra happiness than an extra dollar in the hands of someone who is ten times richer.5 But none of this invalidates economics; it just means we have to reform it.

The new cost–benefit analysis

For economics provides us with the vital tool of cost–benefit analysis as the central method of policy evaluation. Cost–benefit analysis makes it possible for us to maximize social wellbeing without Big Brother working out everything in the central committee office. Instead, it relies on individual decision-makers comparing the costs and benefits of every policy, and choosing to do those where the benefits exceed the costs. This works because the costs (properly measured) are the benefits which would follow from the next best use of the same resources. So if the benefits exceed the costs, total benefits increase and so does social wellbeing.6

What a wonderful idea. The issue of course is how to measure the costs and benefits. At present the standard approach is to measure costs and benefits in dollars (or in whatever is the local currency). The benefits need not be actual dollars received (like, for example, the extra income due to more job training) – they can also be, for example, the advantage of a bridge which cuts down journey times. In such a case the advantages are measured in terms of the amount of money people would be ‘willing to pay’ for having the bridge – and this in turn can be inferred from the costs people incur in order to save time in other contexts.7

But suppose we want to measure the benefits to society of better mental health, or more stable families, or safer communities, or less unemployment. How on earth could we measure these benefits in terms of the money people are willing to pay for them? There is no plausible way of collecting the relevant evidence, since they are not things upon which people make informed choices based on the observable costs and benefits they bring. They are aspects of life in which people are heavily influenced by things that just happen to them (often from ‘outside’). That is precisely why the government has to get involved in them – because voluntary exchange in the market won’t produce an efficient outcome.

There are many reasons why markets can fail to be efficient. There are ‘externalities’, where one person affects another’s welfare not through a voluntary agreement between them but directly. Externalities are pervasive – they include redundancy, the impact of advertising, the experience of crime, and the values we absorb from other people. A second cause of ‘market failure’ is the existence of public goods, like open space, where charging for use is inefficient. And a third is the existence of information imbalances, where the buyer has no idea of the quality of what the seller is offering. All these factors have huge impacts on human welfare and call for government action. And they make it impossible to measure the benefits of a policy by the money people would be willing to pay for it.

So we need a reformed economics where benefits are measured in units of happiness. Then, if the government has a given sum of money to spend (determined by political forces), it should be spent to produce the greatest additional happiness. This is the policy principle we discussed in Chapter 1. For a policy to be justified, it must produce enough happiness per dollar spent – a sufficient bang for the buck.

Is this way of thinking about policy just pie in the sky? No – something similar has been happening for twenty years in the British National Health Service. The question there is which treatments the service can afford. And the answer is to accept all those treatments which deliver enough improvement in the quality of life relative to the money spent on the treatment – or enough extensions to the length of life itself. Since coherent policy-making requires one single criterion, which includes both the length of life and its quality, the criterion is known as Quality-Adjusted Life Years or QALYs.8

There is no reason why a similar approach should not be applied to all public expenditure. Since our concept of the quality of life is ‘happiness’, a suitable name might be HALYs – Happiness-Adjusted Life Years. Policies would then have to be justified on the basis of their HALYs per dollar.9 If you object to this criterion, please tell me a better one. For there is currently no overall criterion – just a jumble of incommensurable objectives.

The proposed approach would not supersede existing cost–benefit analysis; it would use the existing framework, but go beyond it. Generally, the impact of policies on happiness would be measured directly (ideally through proper controlled experiments or otherwise through naturalistic evidence). But in other cases the impact would, as now, be measured by ‘willingness-to-pay’. But in these cases we should remember that a poor person’s dollar produces more happiness than a rich person’s. So the estimates of a person’s willingness-to-pay should be multiplied by the extra happiness produced per dollar. The result of this calculation is once again a measurement in units of happiness.

Let us be clear. Any cost–benefit analysis which just adds up dollars has no ethical foundation, and this applies to most existing cost–benefit analyses.10 Instead, we should measure benefits in terms of happiness. These can then be added up across everyone affected or, if the policy-maker chooses, more weight can be given to changes in happiness affecting those whose initial happiness was low. Governments are increasingly interested in using happiness as the criterion for judging policies. New Zealand, France, Sweden, the UK, Bhutan and the United Arab Emirates are all now using it as a criterion (among others).11 But what difference will this make to actual policy choices?

We have already seen a large number of areas which require more attention and more public money. We want much more spent on people suffering from depression, anxiety disorders, drugs, alcohol and domestic conflict. We need more help for children, for their parents and for their communities. In many cases the extra money will save as much as it costs, through savings on other types of public expenditure, but the cost does need to be incurred in the first place.

Economists should be actively involved in all these areas, because they have the right analytical tools for the job. They are well placed to analyse overall national priorities (that is, which areas need new policies), and then which specific policies are the most cost-effective.

On top of that economists have special expertise in areas traditionally called ‘economic’. Among these, I shall only look at those areas where the happiness perspective leads to radically new conclusions about policy priorities:

- economic growth versus economic stability

- low unemployment

- wage inequality, globalization and robots

- the redistribution of income

- world poverty, and

- international migration.

Economic growth versus economic stability

In 2003, the Chicago economist Robert Lucas gave his Presidential Address to the American Economic Association.12 He argued that economic growth was all-important and that, by comparison, fluctuations in employment mattered very little. If you think income equals happiness, his logic is inescapable – growth at compound interest takes a country to extraordinary heights. But happiness research shows that it is more important for a country to have low unemployment and a stable economy than to have higher long-term growth.

For unemployment is, for most people, one of the worst experiences of life, and as painful on average as being widowed or separated. The loss to the unemployed individual is around 0.7 points of life-satisfaction. On top of this, a high unemployment rate increases the anxiety and insecurity of people in work – they fear for their job and how to get another one if they lose their present one. This spill-over effect quadruples the total loss of happiness when one person is out of work.13

People also dislike fluctuations in income. As the Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman discovered, people hate losing a dollar twice as much as they love gaining a dollar.14 So economic fluctuations are real destroyers of happiness, and economic stability should be a crucial objective of policy.

Higher long-run economic growth is much less important. There is no conclusive proof that whole societies become happier when they become richer.15 One problem is that as I get richer, so do most other people – so the norm with which I compare my income rises and my overall happiness rises less than I might have expected.16 However, governments often think that faster growth will solve their problems with the budget. This is much less true than it might appear. If wages rise, people certainly pay more taxes. But at the same time wages in the public sector have to rise in line with wages in the rest of the economy. So the government has to pay more for a given level of service. This extra expenditure largely cancels out the extra tax receipts.17 The main advantage to governments from faster long-term growth is that it raises the tax base from which to repay existing government debt.18 This is a real advantage, but not so important that we should be willing to imperil economic stability for the sake of faster growth.

Unfortunately, that is exactly what happened before 2008. In most countries priority was given to economic growth. The banks argued (wrongly as it turned out) that, if they were less tightly regulated, this would produce higher growth. So governments deregulated the banks as they were asked to. And the rest is history.

Growth is surely desirable and it will happen anyway. It is an aspect of human creativity – we will go on finding better ways to do things as long as humans exist. But faster long-term growth is not an overriding criterion. The leading objectives of macro-economic policy should be stable unemployment and low inflation. In most countries, this is now the job of an independent central bank.

Low unemployment

But unemployment should be more than stable – it should be low. As we said above, unemployment is a prime destroyer of happiness. It makes people feel worthless and unwanted. So when an individual becomes unemployed, the psychic pain is three times greater than the pain from loss of income. And on top of that other people become anxious about their own future, which quadruples the total loss of happiness.19 So how can unemployment be kept low without the tightness of the labour market creating wage inflation and thus higher prices?

Unemployment in Western Europe

Germany

Germany

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

France

France

In the 1980s I spent ten years of my life researching this issue with some wonderful colleagues (see My Thanks), and then the next ten years trying to get European governments to implement our ideas. Between the 1960s and the 1980s there was a massive rise in unemployment in most Western countries (see Figure 11.1 above). This was mainly because increased wage pressure had caused high inflation, and then, to reduce the inflation, governments and central banks had deliberately caused higher unemployment. By 1990 inflation was back to normal levels, but unemployment remained high, in spite of the presence by then of large numbers of unfilled job vacancies.20

What explained this high level of unemployment when there were still many unfilled vacancies? As our research showed, it was largely due to the system of unemployment benefits. In Europe, benefits were typically available indefinitely and without conditions such as ‘you must accept a job if offered’. So, once unemployment had been driven up, many people adjusted to it, however grudgingly. The exception was in countries like Sweden where benefits were less easily available and for a shorter time period; instead, there were active labour market policies to help people back into work – policies like active placement and supported work. So our research concluded that to achieve low unemployment there had to be stricter administration of benefits, linked to more positive help for the unemployed. And, in wage bargaining, it had to be impossible for small groups of insiders to force up the overall wage level.

Since 1990 unemployment has fallen back to its earlier level in some countries but not in others. It has fallen sharply in Germany, Denmark, the Netherlands and Britain, but not in France or Spain. The countries which have done well have indeed introduced stricter conditions for receiving benefits, plus more active labour market policies, and they have avoided wage bargaining systems where small groups of insiders set wages for whole industries.21 France and Spain have done much less.

But has the lower unemployment actually increased the happiness of those who would otherwise be out of work? The presumption must be yes, but there could be two objections. First, are the extra jobs good enough? The quality of jobs is of course really important. So are we forcing people into bad jobs which are so much worse than their previous job that they would be better off continuing to search? The difference in levels of happiness between the jobs is not large enough for this to be at all likely.22 Second, some of the jobs are not ‘real jobs’ but jobs in ‘community service’, paying little more than unemployment benefit. Can such jobs make people happier than being unemployed? The answer from a number of surveys is yes, people feel much better doing community service jobs than doing nothing at all.23

So what is happening? If unemployment is so wretched, why do we have to push people into work. The answer is simple – unemployment can cause not only misery, but helplessness and despair. Only by getting people active can we help them to overcome despair. That is why a group of us have proposed a radical version of Welfare-to-Work.24 This requires that every healthy person who has been out of work for over a year should be offered useful activity, paid at the rate for the job. At the same time they should cease to be eligible to claim benefits while being inactive. The principle is, if you like, a right to work linked to a corresponding duty to contribute, in return for income.

In 1997 Tony Blair’s government accepted this proposal for people under twenty-five, and the resulting ‘New Deal’ recovered at least a half of its costs through savings on benefits – paying fewer people for useless inactivity.25 Then, as youth unemployment fell, the programme became diluted. But in 2009, when unemployment increased again, the government renewed its attack on youth unemployment with a Future Jobs Fund. Again, this recovered about one half of its public cost through savings on unemployment benefits.26

Many European countries, influenced by Britain, have followed a similar path: more active help for the unemployed linked to much tighter conditions for receiving unemployment benefits. Denmark was an early mover during the 1990s.27 But the most striking reforms were the Hartz reforms in Germany beginning in 2003. Though highly controversial, these laid the foundation for Germany’s low unemployment in more recent years. One can of course have low unemployment by a fairly draconian system of unemployment relief, as in the US. But a more humane approach to follow is that of Germany or Denmark. Economists in every country need to press for this kind of approach.

One thing that should not be provided is an income guarantee without conditions. Empirically, this reduces the number of people in work, as it has in France. Even worse than that is the idea of a Universal Basic Income, where everyone automatically receives a given basic income whether they need support or not. This is even more expensive than an income guarantee. But both ideas are morally questionable. Income does not just happen: it has to be produced. So if you want a claim on income, you should contribute to the production of it – if you are able to.

Of course there are many people who are not able to work because they are too ill. In a civilized society they are provided with a reasonable income without undue harassment. But governments naturally worry about the cost of these benefits. One approach is to question people closely to see if they really are sick. But a one-off test of ‘work capability’ is not an adequate way of deciding if they are, because so many illnesses (both mental and physical) fluctuate from week to week in their impact. Terrible misery can be caused if people are tested on a rare good day and subsequently denied benefits. Such crass testing often leads eventually to further incapacity and extra cost. So any test must include a proper medical assessment.

But the best way to reduce the cost of sickness benefits is to reduce the number of people who are sick. In most countries about half of the people on sickness benefit are suffering from mental-health problems, generally depression or anxiety disorders. But typically under half of these people are actually in treatment for their condition, and most of them are on anti-depressants which have clearly not restored them to health. The solution must be that all these people – when they first qualify for benefit – should be given a psychological assessment by a professional therapist and referred for appropriate psychological treatment.28 Any other approach can lead to real misery.

Wage inequality, globalization and robots

If unemployment is devastating, low relative wages are also demeaning, especially if they are insecure as well. Since the 1980s wage inequality has risen sharply in most English-speaking countries – though little, if at all, in many others (see Table 11.1).

What is causing this new inequality? A common view says it is globalization. And there are obvious examples where employment and wages have been hit hard by foreign competition.29 However, there is nothing new in this. In the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s Western textiles, steel mills, shipbuilding and consumer electronics were hit successively by competition from emerging countries. Such impacts are severe and they require active labour market policies (including the retraining and placement of displaced workers) and investment subsidies in the towns and cities where the jobs are disappearing. But foreign competition is not the biggest problem: the central issue is technology.30

In the sixteenth century Thomas More complained in his work Utopia that ‘sheep are eating up people’. In the twenty-first century it is machines that are displacing less-skilled workers, while at the same time increasing the demand for people with higher skills. This process inevitably raises the wage premium for skill – unless the supply of skilled workers increases at the same rate as the demand increases. As Table 11.1 implies, the supply of skilled people has not risen fast enough in Britain, the USA or Australia. Although the rate of return to skill acquisition is high,31 our social institutions have failed to reduce the number of unskilled people fast enough.32 The result is an ever-greater gap in wages. We are moving towards a two-class society: of graduates (with degrees) and non-graduates (often with few skills). This bi-modal structure of educational achievement is much less evident in continental Europe than it is in Britain or the USA.

Table 11.1

Inequality has risen in some English-speaking countries, but to a lesser degree elsewhere

Weekly earnings (90th percentile divided by 10th percentile) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 2010 | 2016 | Change 1980–2016 |

|

| Australia | 2.7 | 3.6 | 3.5 | +0.7 |

| United Kingdom | 2.7 | 3.7 | 3.5 | +0.9 |

| United States | 3.6 | 5.1 | 5.5 | +1.9 |

| Finland | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.6 | +0.1 |

| France | 3.0 | 2.9 | ||

| Germany | 3.3 | 3.4 | ||

| Italy | 2.3 | 2.4 | ||

| Japan | 2.6 | 2.9 | 2.8 | +0.2 |

| Sweden | 2.0 | 2.4 | 2.4 | +0.3 |

So what are the best ways of developing the skills of non-graduates? The main answer is apprenticeship – for many reasons. If you are practically minded, learning makes more sense when you can experience how it is applied, day by day. And if at the same time you earn money, there are powerful motives for learning. The Germanic nations (Germany, Austria, the Netherlands and parts of Switzerland) have the best developed apprenticeship systems. In consequence they have the smallest fraction of young people without skilled qualifications and they have the lowest levels of youth unemployment.33 So the basic way to reduce wage inequality is to reduce the number of people without a skill.34 This has always been true, and it will become increasingly important as robots continue to multiply.

However, there is another concern about robots: that they will cause mass unemployment. Is this likely? Economists have always downplayed the fears of technological unemployment. And so far they have always been proved right. After some initial suffering, the weavers found other jobs. So did the horsemen, the ploughmen, the miners, the steel workers and a host of others whose jobs were destroyed by technological advances. Overall, unemployment did not trend upwards, mainly because, when jobs are destroyed and workers are released into the market, new jobs get created. So the overall number of jobs does respond to the number of job-seekers – between 1855 and 2017 the British labour force grew by 168 per cent and, remarkably, so did the number of jobs.35 There is a market mechanism which increases employment in line with the effective supply of labour. The main issue is at what wage? Robotization will bring downward pressure on the wages of the unskilled, which is why it is so important to reduce the number of unskilled people.

The redistribution of income

But should the state also redistribute money to people with low earning power? Of course it should, for the age-old reason that a dollar transferred from a rich person to a poor one causes more extra pleasure for the poor person than pain to the rich one.36 Economists have always believed this. At the same time they have usually argued that the size of the pie shrinks as you redistribute the pie. So there is some optimal level of redistribution where the equity case for more redistribution is just offset by the efficiency case against it.37

What difference does it make to this argument when we recognize that money has a smaller influence on happiness than economists have tended to assume? The answer is none at all. Even if additional money for the poor will bring them less extra happiness than some have thought, less money for the rich will also cause them less misery than might have been expected.

But there are two new factors coming from the happiness perspective which do introduce massive changes into the redistribution debate. The first makes one more enthusiastic about redistribution. This is the importance of social comparisons. As we have seen, people’s happiness depends on their relative income as well as their absolute income. So people expend long hours away from the family and friends in order to increase their relative incomes. But for the society as a whole this attempt to raise relative income is a chimera. It can’t be done. So what can be done to prevent this source of waste? The answer is simple. When I earn more, I raise the bar against which others compare their income. This makes them worse off. That is a negative ‘externality’, a form of pollution. And the way to deal with pollution is to tax it. So, up to some level, taxing income improves the efficiency of the economy, by reducing the time wasted on the zero-sum rat race.38 If this is so, we can obviously undertake more redistribution than we would otherwise, before worrying about its effects on the size of the pie.

But another factor makes one less enthusiastic about redistribution. This is the issue of the budget constraint. For practical purposes the proportion of GNP which is raised in taxes has to be taken as given. Money given out to poorer people has to come out of this pot, and we have to think hard about whether money used in this way does more to increase happiness than money provided in direct services aimed at reducing misery.

Is it better to relieve misery by handing out cash or by providing better services? Economists have always preferred redistribution in cash rather than in kind, in the belief that people know more than the state does about what makes them happy. But modern behavioural economics has revealed countless ways in which people’s choices are inefficient – they fail to choose what will in fact make them happiest.39 And they are often desperate for help. So an alternative way to use precious tax receipts is through services which help people to help themselves. The previous chapters have shown many ways in which this can be done. And if we look at the cost-effectiveness of these ‘in kind’ policies, they frequently do better than simple cash redistribution.40

Table 11.2 is a very crude back-of-the-envelope analysis using British data. The issue is, how can we shift people out of misery at the lowest cost? Misery is defined as having life-satisfaction at 3 or below (on a scale of 1–7).41 From the British Household Panel Study we can then estimate how much money would have to be spent in order to have one less person in misery – depending on the way we go about it. The table suggests that the least efficient of the four options shown is cash redistribution. The most efficient is more money for treating mental illness,42 and the next most efficient is active labour market policy to reduce unemployment. To devise a more evidence-based multi-pronged strategy for reducing misery is a major challenge which economists need to grasp. Many people believe that household income inequality is the supreme evil, and highlight the correlation between income inequality and poor outcomes to illustrate this.43 But many of these poor outcomes can be improved at less cost by direct help, rather than by the further redistribution of income.

Table 11.2

Average cost of reducing the numbers of people in misery, by one person

| £000S per year |

|

| Poverty Raising more people above the poverty line |

180 |

| Unemployment Reducing unemployment by active labour market policy |

30 |

| Physical health Raising more people from the worst 20 per cent of illness |

100 |

| Mental health Treating more people for depression and anxiety |

10 |

For many egalitarians like myself, these findings have come as quite a shock. For many of the happiest countries in the world are the most egalitarian, including those in Scandinavia. And in two compelling books Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett have shown a powerful correlation (across countries and across US states) between income inequality and many bad outcomes (including low life expectancy, bad mental health, use of narcotic drugs, crime, teenage pregnancy and the like).44 So if income inequality ‘affects’ all these things, one would expect it to affect average happiness as well.45 Yet in international comparisons, scholars such as John F. Helliwell, who favour equality, have generally failed to pick up an effect of income inequality upon the average happiness of nations, other things being equal.46

So what is going on? The answer I suggest is that income inequality has less causal effect on other outcomes than might appear from simple correlation. Instead, both inequality and the other outcomes are jointly determined by a third factor: the spirit of mutual respect in the society. In Scandinavian countries for example there is a strong spirit of mutual respect. This is reflected in good social services which simultaneously improve both the equality of income and all the other outcomes that we value.

This interpretation of the data is supported by a rather remarkable finding. When we compare countries, those with a more equal distribution of happiness (rather than of income) are indeed much happier.47 This too is surely not a causal relationship by itself. But it reflects the fact that, where there is more mutual respect, a multitude of policies are put in place which reduce misery. In addition the general social climate improves. For example, when happiness is more equally distributed, there is more social trust, which benefits everybody.48 Thus, as Wilkinson and Pickett point out, even the rich have better outcomes in more equal societies. But it is not mainly income equality as such which is producing the greater happiness, but a more general spirit of mutual respect, working through a whole host of channels. This spirit of mutual respect is a key factor affecting the happiness of nations.

World poverty

Up to now our focus has been on the richer economies. But shouldn’t priorities be different in the developing world? Not as much as you might think. In poor countries, poverty explains slightly more of the prevailing misery than in rich countries. But even in poor countries there are many other causes of misery beyond poverty and physical illness. Mental illness is at least as big a cause of misery as physical illness is.49 And in some countries unemployment is another major problem.

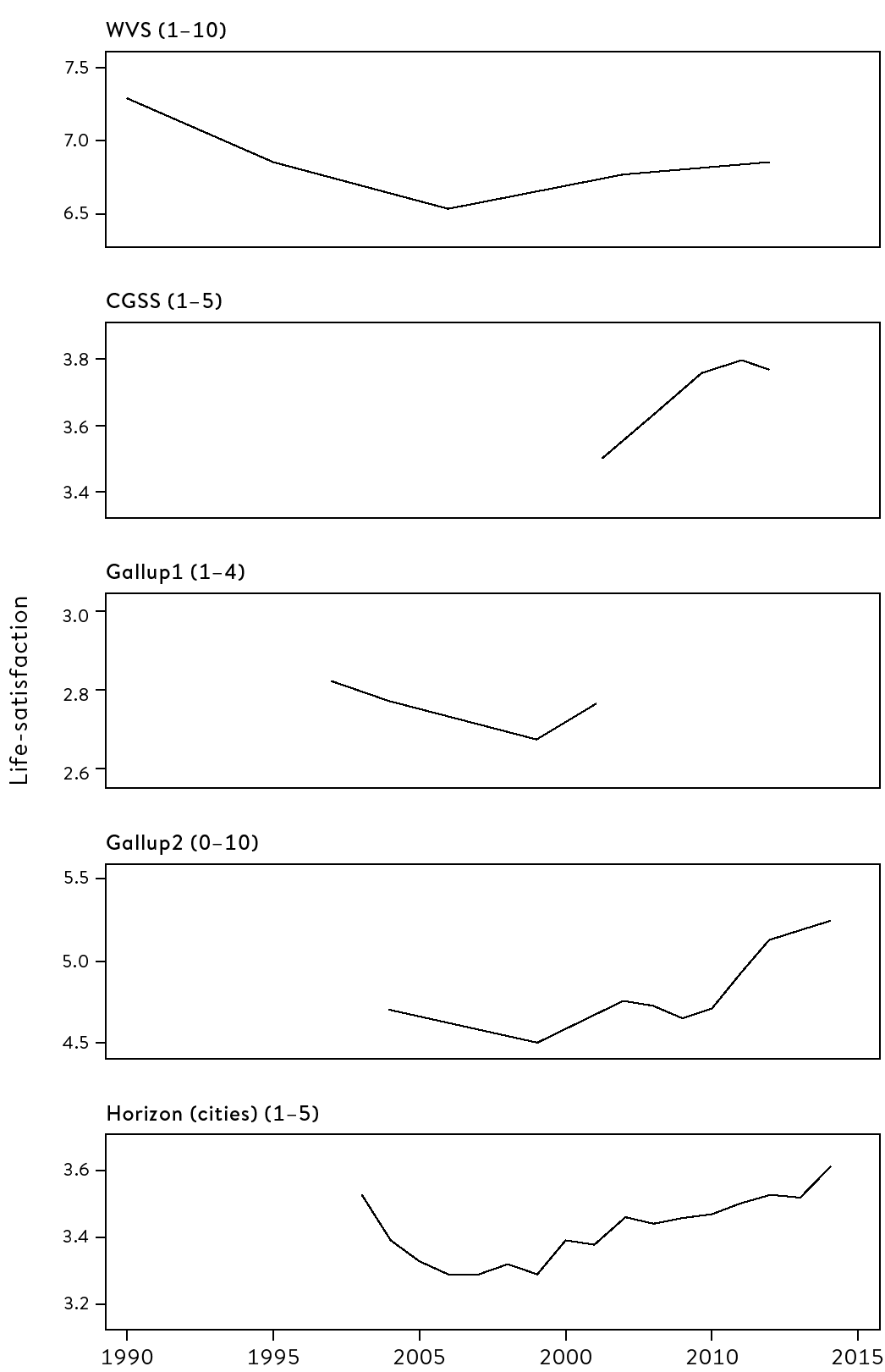

Since 1990 there has been a massive fall in world poverty, especially in China. But what has it done for happiness? Among countries for which we have data for fifteen years or more, there is no relation between the rate of economic growth and the change in people’s happiness.50 In fact, in China, the world’s most rapidly developing major country, happiness today is little higher than it was in 1990. This is such an astonishing fact that I reproduce Richard Easterlin’s graph (Figure 11.2) showing five surveys, all of which tell a consistent tale. Virtually every urban home in China now has a colour TV, air conditioning and a washing-machine; and nine in ten have a personal computer. But people appear to be little happier.

Average happiness in China, using five studies, 1990–2015

What can explain the fall in happiness in China in the 1990s? A part of the story is the massive restructuring of the economy which began at that time. Within a period of twelve years, ‘50 out of 78 million lost their jobs in traditional state-owned enterprises, and another 20 million were laid off in urban collectives’.51 Unemployment soared. But so did GDP, as activity shifted from the low productivity factories which were closing, to higher productivity factories which expanded. But this was little comfort to the low-income third of income earners. It was their happiness which fell, while the happiness of the top third was unaffected. And again it was the bottom third who mainly lost the safety net of income and health care to which they had been entitled. This is how Richard Easterlin puts it:

Why are unemployment and the social safety net so important? These two factors bear most directly on the concerns foremost in shaping personal happiness – income security, family life, and the health of oneself and one’s family. It is these concerns that are typically cited by people worldwide when asked an open-ended question as to what is important for their happiness. In contrast, broad societal matters such as inequality, pollution, political and civil liberties, international relations, and the like, which most individuals have little ability to influence, are rarely mentioned. Abrupt changes in these conditions may affect happiness, but for the most part, such circumstances are taken as given. The things that matter most are those that take up most people’s time day after day, and which they think they have, or should have, some ability to control.52

Wise words. But there remains a puzzle. By now unemployment in China has fallen back to its original 1990 level. So why, with all that extra comfort, are people not much happier now than they were in 1990? There are two obvious possibilities. One is that people now use a higher standard of living with which to compare their own – the usual problem of social comparisons. There is some evidence of that.53 The other is the breaking of social ties. From a static society where people had well-established connections, many have moved to towns in the biggest migration known to man. They miss their social ties and it takes time to develop new ones. So a crucial role of development policy must be to foster real communities in the new urban areas.

In India there are fewer data on wellbeing than in China. But, according to the Gallup World Poll, average life-satisfaction has fallen by 0.7 points (out of 10) since 2008–10 – a dramatic fall.

The challenge to development economists is clear. Grinding poverty has to be eliminated. It destroys happiness and shortens lives.54 But it is wrong to go for helter-skelter growth. What is needed is a deliberate process whereby genuine communities are maintained or created – communities which give people the feeling of belonging and purpose. It is no easy task.

Is international migration the answer?

Of course, one remedy for world poverty is international migration from poor countries to rich ones. Economists tend to favour migration as a solution, because individuals are likely to increase their income. But what should one conclude about international migration, if wellbeing is what we care about?

The first obvious point is that migration happens because migrants are looking for a better life. And on average they find it. The World Happiness Report for 2018 documents this, using data for over 150 countries.55 On average, international migrants increase their happiness by 0.6 points (out of 10) – a substantial gain, similar to the gain when an unemployed person finds work.

In fact migrants who move from a less happy country to a happier one become almost as happy as the existing residents in the country where they end up.56 And surprisingly this happens almost as soon as the migrants arrive. Once they are there, the majority of migrants increase their incomes rapidly, but this does not increase their happiness any further – perhaps because they increasingly compare their incomes with those of other people in their new home country. Similarly the second generation, the children of migrants, are as happy as their parents (perhaps for the same reason) – but much happier than their parents were before they moved.

So why do migrants become happier? It’s not just their higher income. Migrants value the social aspects of their society just as much as everyone else does – especially social support, freedom, lack of corruption and generosity.57 So they become happier mainly because the society they join is nicer – and not only because it is richer.

From the migrant’s point of view, their move to another country greatly increases their happiness. But what about the happiness of the two other groups of people affected by the migration? One is the family that the migrants leave behind. According to the evidence, they remain as satisfied with life as before, partly because they often receive money sent back by the migrants (in 2015 the total of such remittances in the world was $500 billion per year).58

The other group affected by migration are the people who are already living in the host country. We discussed them in the last chapter. Many gain, but others lose, and hence the issue can become fraught. A decisive factor must be the rate at which immigration occurs. As Paul Collier of the University of Oxford argues powerfully, we cannot have uncontrolled immigration into rich countries. As globalization proceeds and migrant communities in richer countries become larger, there will be ever larger numbers of people wanting to migrate.59 So there have to be some controls on the rate of annual migration into any rich country.

The optimal level has to reflect the huge potential gains to migrants, but also the legitimate claim of existing residents to determine who comes to live with them.60 The optimum will surely allow for significant levels of migration, so that as time passes rich countries will become increasingly diverse. But best of all would be a rapid move in the poorer countries towards the wealth and civic standards of the West. This argues the need for a much higher level of foreign aid from richer nations to poor ones.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the economic method is the only way to think about policy priorities: we need to get the most benefit from any money that we spend. But the benefits should be measured in terms of happiness – and not of money. This thinking applies to every issue considered in this book, economic or otherwise. It should apply equally to materialistic projects (like most infrastructure) and to policies with a more social or psychological objective.

The common presumption in favour of physical infrastructure needs to be balanced with a greater concern for the human infrastructure. But the economy does matter, in many ways.

- Economic stability is crucial to our happiness and it is more important than faster long-term growth. We should not imperil stability for the sake of growth.

- Low unemployment is vital and it requires active help to unemployed people to get work. They deserve a right to work within twelve months of becoming unemployed, linked to the ending at that point of unemployment pay for doing nothing.

- Growing inequality is best tackled by providing everyone with a genuine skill (typically through an apprenticeship).

- More cash redistribution may be a less efficient way to reduce misery than many of the ways discussed in earlier chapters.

- Economic development in poor countries should involve a proper balance between increased output and civilized relations at work and in the community.

- International migration brings great increases in happiness to the migrants. But the optimal level of immigration must also allow for the real impact on local residents.

- In all economic decisions there is a major social element that must be considered, for good or ill.

So the happiness approach should become the mainstream method used by economists in the field of public policy. This is now urgent. Behavioural economics has already transformed the way in which many economists explain behaviour. But it requires happiness economics to analyse what types of behaviour are desirable.61 So happiness economics should become a standard branch of the subject and a standard topic in the economics curriculum.

However, whatever economists advocate, in the end it is politicians who decide. How can they contribute to a happier world?