“IN YOUR FACE . . . ALL OVER THE PLACE”

Advertising Is Our Environment

![]()

ADVERTISERS LIKE TO TELL PARENTS THAT THEY CAN ALWAYS TURN OFF THE TV to protect their kids from any of the negative impact of advertising. This is like telling us that we can protect our children from air pollution by making sure they never breathe. Advertising is our environment We swim in it as fish swim in water. We cannot escape it. Unless, of course, we keep our children home from school and blindfold them whenever they are outside of the house. And never let them play with other children. Even then, advertising’s messages are inside our intimate relationships, our homes, our hearts, our heads.

Advertising not only appears on radio and television, in our magazines and newspapers, but also surrounds us on billboards, on the sides of buildings, plastered on our public transportation. Buses now in many cities are transformed into facsimiles of products, so that one boards a bus masquerading as a box of Dunkin’ Donuts (followed, no doubt, by a Slimfast bus). The creators of this atrocity proudly tell us in their ad in Advertising Age, “In your face … all over the place!” Indeed.

Trucks carry advertising along with products as part of a marketing strategy. “I want every truck we have on the road making folks thirsty for Bud Light,” says an ad in Advertising Age, which refers to a truck as a “valuable moving billboard.” Given that almost half of all automobile crashes are alcohol-related, it’s frightening to think of people becoming thirsty for Bud Light while driving their cars. A Spanish company has paid the drivers of seventy-five cars in Madrid to turn their cars into Pall Mall cigarette packages, and hopes to expand its operation throughout Spain. Imagine cars disguised as bottles of beer zipping along our highways. If we seek to escape all this by taking a plane, we become a captive audience for in-flight promotional videos.

Ads are on the videos we rent, the shopping carts we push through stores, the apples and hot dogs we buy, the online services we use, and the navigational screens of the luxury cars we drive. A new device allows advertisers to print their messages directly onto the sand of a beach. “This is my best idea ever—5,000 imprints of Skippy Peanut Butter jars covering the beach,” crowed the inventor. Added the promotion director, “I’m here looking at thousands of families with kids. If they’re on the beach thinking of Skippy, that’s just what we want.” Their next big idea is snow imprinting at ski resorts. In England the legendary white cliffs of Dover now serve as the backdrop for a laser-projected Adidas ad. American consumers have recently joined Europeans in being offered free phone calls if they will also listen to commercials. Conversations are interrupted by brief ads, tailored to match the age and social profiles of the conversants. And beer companies have experimented with messages posted over urinals, such as “Time for more Coors” or “Put used Bud here.”

The average American is exposed to at least three thousand ads every day and will spend three years of his or her life watching television commercials. Advertising makes up about 70 percent of our newspapers and 40 percent of our mail. Of course, we don’t pay direct attention to very many of these ads, but we are powerfully influenced, mostly on an unconscious level, by the experience of being immersed in an advertising culture, a market-driven culture, in which all our institutions, from political to religious to educational, are increasingly for sale to the highest bidder. According to Rance Crain, editor-in-chief of Advertising Age, the major publication of the advertising industry, “Only eight percent of an ad’s message is received by the conscious mind; the rest is worked and reworked deep within the recesses of the brain, where a product’s positioning and repositioning takes shape.” It is in this sense that advertising is subliminal: not in the sense of hidden messages embedded in ice cubes, but in the sense that we aren’t consciously aware of what advertising is doing.

Children who used to roam their neighborhoods now often play at McDonald’s. Families go to Disneyland or other theme parks instead of state and national parks—or to megamalls such as the Mall of America in Minneapolis or Grapevine Mills in Texas, which provide “shoppertainment.” One of the major tourist destinations in historic Boston is the bar used in the 1980s hit television series Cheers. The Olympics today are at least as much about advertising as athletics. We are not far off from the world David Foster Wallace imagined in his epic novel Infinite Jest, in which years are sponsored by companies and named after them, giving us the Year of the Whopper and the Year of the Tucks Medicated Pad.

Commercialism has no borders. There is barely any line left between advertising and the rest of the culture. The prestigious Museum of Fine Arts in Boston puts on a huge exhibit of Herb Ritts, fashion photographer, and draws one of the largest crowds in its history. In 1998 the museum’s Monet show was the most popular exhibit in the world. Museum officials were especially pleased by results of a survey showing 74 percent of visitors recognized that the show’s sponsor was Fleet Financial Group, which shelled out $1.2 million to underwrite the show.

Bob Dole plays on his defeat in the presidential election in ads for Air France and Viagra, while Ed Koch, former mayor of New York City, peddles Dunkin’ Donuts’ bagels. Dr. Jane Goodall, doyenne of primatology appears with her chimpanzees in an ad for Home Box Office, and Sarah Ferguson, the former duchess of York, gets a million dollars for being the official spokeswoman for Weight Watchers (with a bonus if she keeps her weight down).

Dead celebrities, such as Marilyn Monroe and Humphrey Bogart and John Wayne, are brought to life through computer magic and given digitized immortality in ads (how awful it is to see classy Fred Astaire dancing with electric brooms and hand vacs). Even worse, advertising often exploits cultural icons of rebellion and anticommercialism. Jimi Hendrix was raised from the dead by Aiwa to sell stereos, and John Lennon’s haunting song “Imagine” is used by American Express. The Beatles’ “Revolution,” Bob Dylan’s classic anthem “The Times They Are A-Changin’,” and Janis Joplin’s “Oh Lord, won’t you buy me a Mercedes-Benz?” have all been used as advertising jingles, appealing to baby boomers’ nostalgia while completely corrupting the meaning of the songs. And the Rolling Stones, those aging rebels, have allowed Sprint to put a straight-pin through the band’s tongue logo. However, when Neil Young recorded a video for his song “This Note’s for You,” which states that he won’t sing for Pepsi or Coke and includes the lines “I don’t sing for nobody/Makes me look like a joke,” MTV refused to run it.

Live celebrities line up to appear in ads and people who simply appear in ads become celebrities. Today little girls constantly rate the supermodels high on their list of heroes, and most of us know them by their first names alone . . . Cindy, Elle, Naomi, Iman. Imagine—these women are heroes to little girls, not because of their courage or character or good deeds, but because of their perfect features and poreless skin. Models become more famous than film and television stars and rock stars, and the stars themselves often become pitchmen (and women) for a variety of products ranging from candy to cigarettes to alcohol.

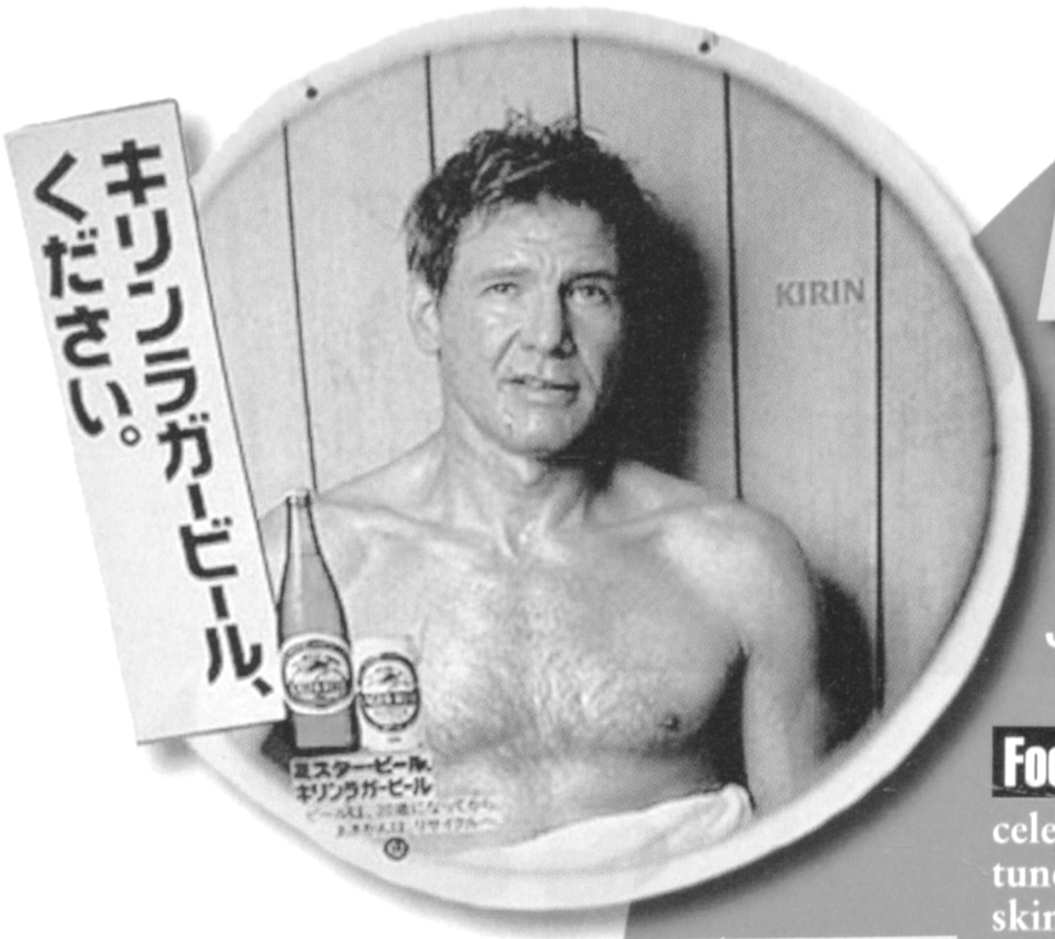

Stars such as Harrison Ford, Woody Allen, Paul Newman, Whoopi Goldberg, and Bruce Willis, who don’t want to tarnish their image in the United States, gladly appear in foreign television ads and commercials. Antonio Banderas and Kevin Costner have pushed cars, Brad Pitt watches, Dennis Hopper bath salts, Michael J. Fox fishing tackle, and Jennifer Aniston shampoo. In a commercial for Nippon Ham, Sylvester Stallone munched sausages at a garden party. After the success of Titanic, Leonardo DiCaprio was paid $4 million to play a noodle-eating detective in a Japanese commercial for credit cards. And in a commercial for Austrian Railways, Arnold Schwarzenegger rebuffs a steward who offers him a drink with the reply, “Hasta la vista, baby” Not surprisingly, he agreed to make the commercial only on the condition that the international media not be told about it. Madonna has a similar deal with Max Factor, which is paying her $6.5 million to sell cosmetics on TV, billboards, and in magazines throughout Britain, Europe, and Asia, but is prohibited from circulating photos from the ad campaign in the United States.

We are also influenced by advertising that we do not recognize as such, like the use of brand names during televised sporting events (during one ninety-minute car race, the word “Marlboro” appeared 5,933 times). In 1983 Sylvester Stallone wrote a letter to the Brown & Williamson tobacco company in which he promised to use their tobacco products in five feature films in exchange for half a million dollars. Compare this with the old days of “Brand X,” the days when Julia Child covered the brand name “Pyrex” on her measuring cup!

Increasingly, films and television shows carry these hidden commercials. Often characters use certain products, the brands are prominently displayed, but the audience remains unaware that money has changed hands. New technology allows advertisers to have products digitally added to a scene, such as a Coca-Cola can on a desk or commercial billboards in the background of baseball games. At the very least, these “commercials” should be directly acknowledged in the credits. Writer and cartoonist Mark O’Donnell suggests that someday there will be tie-ins in literature as well, such as “All’s Well That Ends With Pepsi,” “The Old Man, Coppertone and the Sea,” and “Nausea, and Periodic Discomfort Relief.”

Sometimes the tie-ins are overt. Diet Coke obtained the rights to the cast of the hit series Friends and built a promotion around a special episode of the show that aired after the Super Bowl. In 1997 ABC and American Airlines announced a program that grants bonus miles and vacation credits to enrolled members who can correctly answer questions about shows that recently aired on the network. In the spring of 1998 product peddling on television was brought to new heights (or a new low) when a character in the hit show Baywatch created a line of shoes in her fashion-design class that viewers can actually buy. Stay tuned for Shoewatch.

Far more important than the tie-ins, however, is the increasing influence of advertising on the form and content of films, television shows, and music videos (which aren’t so much like ads as they are ads). Among other things, advertisers prefer that their products be associated with upbeat shows and films with happy endings, shows that leave people in the mood to buy. “People have become less capable of tolerating any kind of darkness or sadness,” says media scholar Mark Crispin Miller. “I think it ultimately has to do with advertising, with a vision of life as a shopping trip.” Steven Stark, another media critic, holds advertising responsible for a shift in television programs from glamorizing private detectives to glamorizing the police. According to Stark, “A detective show often leaves the audience with the impression that the system, police included, is corrupt and incompetent. An audience left with that message is in less mood to buy than an audience reassured, night after night, that the system works because the police are doing their job.”

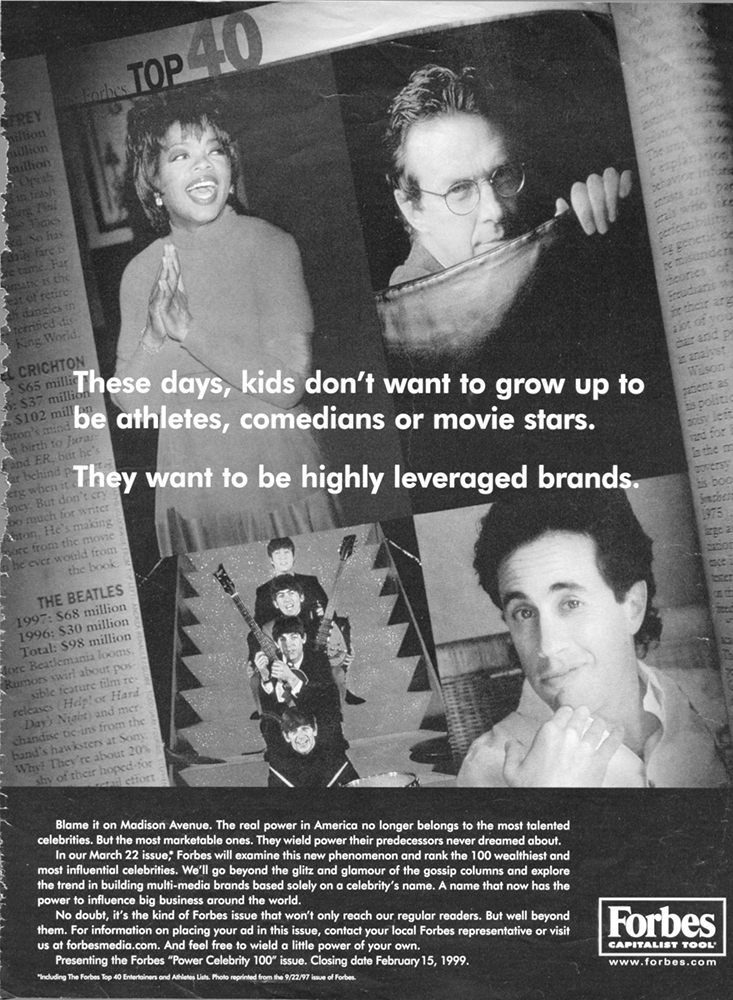

The cast of Seinfeld were the most successful hucksters in TV history, so successful that in 1994 Advertising Age gave their Star Presenter of the Year award to the entire cast. As Jerry Seinfeld, star of the show, said, “It is a good combination. When you’re on TV in a sitcom, there’s a loose reality that lends itself to doing commercials, which are also on TV. As long as you’re on TV pretending to be something you’re not anyway, why not do it for a commercial?” Opening an advertising agency, one of the paths Seinfeld is reportedly now considering, wouldn’t be much of a leap (not that there’s anything wrong with that). No wonder Seinfeld was one of the celebrities featured in a 1999 ad placed by Forbes magazine in Advertising Age that said, “These days, kids don’t want to grow up to be athletes, comedians or movie stars. They want to be highly leveraged brands.” The ad continues, “The real power in America no longer belongs to the most talented celebrities. But the most marketable ones.”

The 1997 James Bond film Tomorrow Never Dies broke new ground for global integrated film tie-ins. In an ongoing effort to raise its profile, beer marketer Heineken USA featured James Bond, portrayed by Pierce Brosnan, in point-of-purchase displays worldwide and also offered a James Bond holiday catalog of electronic devices. During one scene in the film Bond crashes a car into a Heineken truck. Other marketers with major tie-ins to the film include Heublein’s Smirnoff vodka brand, Omega watches, Avis, L’Oreal, and Visa International. More recently, the 1998 hit movie You’ve Got Mail basically costarred America Online, which in turn spent millions on television and online advertising for the movie. “Warner Brothers came to us and we agreed to be as helpful as we possibly could,” said an AOL spokeswoman.

And independent films are becoming as tight with Madison Avenue as are the big flicks. Although I have no evidence that it was intentional, The Brothers McMullen prominently featured Heineken and Budweiser beer, which was ironic given its underlying theme of the havoc wreaked by family alcoholism. According to Ted Hope, the film’s producer, “We struggle with product placement all the time, and I know other producers and directors struggle with it. I actively discourage it in movies but there are times when I contradict myself.”

According to Paul Speaker, director of marketing for the independent production company responsible for Sling Blade, the key “is not only to find opportunities to seamlessly place products, but more importantly to associate brand to the entire film relevance.” In order to appear hip and cool, major clothing manufacturers, such as Dockers, Tommy Hilfiger, and Polo Ralph Lauren, are associating their products with the low-budget independent films that are usually seen as “counterculture.” Hilfiger provided the wardrobe for the independent film The Faculty and, in exchange, the teenage actors in the film appeared in commercials for Hilfiger. Andy Hilfiger, the company’s vice-president of marketing, said, “The cast is great, and they went so well with our clothing.”

The music world is in the game too, as rappers launch clothing lines and designers start record labels. Maurice Malone, who designs sportswear and has a record company, says, “You can use your music videos and your artists on your label to show your clothes,” and, “You can talk about your clothes in the songs and hype the name.” In 1999 designer Tommy Hilfiger sponsored concert tours for the Rolling Stones, Lilith Fair, and Britney Spears. All the musicians wore Hilfiger items onstage, while ads in fashion magazines depicted staged scenes from the concerts.

Not everyone is enthusiastic about this trend. Chris Gore, publisher of the Webzine Film Threat, thinks that sponsorship will inevitably guide what kinds of films get made, discouraging those with less consumer-friendly content. “Think of classic movies, like The Wizard of Oz or Gone With the Wind, and the products that could have been branded with them,” he said. “Not only would that date them, it would be pathetic. We’re not creating classics here—this is about commerce.”

In spite of the fact that we are surrounded by more advertising than ever before, most of us still ridicule the idea that we might be personally influenced by it. The ridicule is often extremely simplistic. The argument essentially is, “I’m no robot marching down to the store to do advertising’s bidding and therefore advertising doesn’t affect me at all.” This argument was made by Jacob Sullum, a senior editor at Reason magazine, in an editorial in The New York Times. Writing about “heroin chic,” the advertising fad in the mid-1990s of using models who looked like heroin addicts, Sullum says, “Like you, I’ve seen . . . ads featuring sallow, sullen, scrawny youths. Not once have I had an overwhelming urge to rush out and buy some heroin.” He concludes from this in-depth research that all critics of advertising are portraying “people not as independent moral agents but as mindless automatons,” as if there were no middle ground between rushing out to buy heroin and being completely uninfluenced by the media images that surround us—or no possibility that disaffected teens are more vulnerable than middle-aged executives. After all, Sullum is not the target audience for heroin chic ads.

Of course, most of us feel far superior to the kind of person who would be affected by advertising. We are not influenced, after all. We are skeptical, even cynical . . . but ignorant (certainly not stupid, just uninformed). Advertising is familiar, but not known. The fact that we are surrounded by it, that we can sing the jingles and identify the models and recognize the logos, doesn’t mean that we are educated about it, that we understand it. As Sut Jhally says, “To not be influenced by advertising would be to live outside of culture. No human being lives outside of culture.”

Advertisers want us to believe that we are not influenced by ads. As Joseph Goebbels said, “This is the secret of propaganda: Those who are to be persuaded by it should be completely immersed in the ideas of the propaganda, without ever noticing that they are being immersed in it.” So the advertisers sometimes play upon our cynicism. In fact, they co-opt our cynicism and our irony just as they have co-opted our rock music, our revolutions and movements for liberation, and our concern for the environment. In a current trend that I call “anti-advertising,” the advertisers flatter us by insinuating that we are far too smart to be taken in by advertising. Many of these ads spoof the whole notion of image advertising. A scotch ad tells the reader “This is a glass of Cutty Sark. If you need to see a picture of a guy in an Armani suit sitting between two fashion models drinking it before you know it’s right for you, it probably isn’t.”

And an ad for shoes says, “If you feel the need to be smarter and more articulate, read the complete works of Shakespeare. If you like who you are, here are your shoes.” Another shoe ad, this one for sneakers, says, “Shoe buying rule number one: The image wears off after the first six miles.” What a concept. By buying heavily advertised products, we can demonstrate that we are not influenced by advertising. Of course, this is not entirely new. Volkswagens were introduced in the 1960s with an anti-advertising campaign, such as the ad that pictured the car and the headline “Lemon.” But such ads go a lot further these days, especially the foreign ones. A British ad for Easy jeans says, “We don’t use sex to sell our jeans. We don’t even screw you when you buy them.” And French Connection UK gets away with a double-page spread that says “fcuk advertising.”

A Sprite campaign plays on this cynicism. One commercial features teenagers partying on a beach while drinking a soft drink called Jooky. As the camera pulls back, we see that this is a fictional television commercial being watched by two teens, who open their own cans of Jooky and experience absolutely nothing. “Image is nothing. Thirst is everything,” says the slogan. However, there is nothing in the ad about thirst—or taste, for that matter—or anything intrinsic to Sprite. The campaign is about nothing but image. Of course, what other way is there to sell sweetened, flavored carbonated water? If thirst is really everything, our best bet is water, and not high-priced bottled water either, such as Evian, which costs more than some champagne (no wonder that Evian backward spells “naive”).

When Nike wanted to reach skateboarders, it had to overcome the fact that skateboarders are “about the most cynical bunch of consumers around” and often downright hostile to the idea of Nike entering the market. By putting a humorous spin on a powerful insight about how skateboarders want to be treated, Nike created the “What if we treated all athletes the way we treat skateboarders?” campaign, which has “won over skateboarders around the country and made them believe that Nike knows them and has the guts to defend them and their sport.” Who cares if this is true—what is important is that skateboarders believe that it is true.

Some advertisers use what they chillingly call “viral communications” as a way to reach teenagers alienated from traditional forms of advertising. They use posters on construction sites and lampposts, sidewalk markings, and e-mail to infiltrate youth culture and cultivate the perception that their product is hot. One marketing consultant suggests picturing the mind as a combination lock and says, “One has to know what the particular stimuli are that are the clicks heard by the inner mind of the target market and then allow the target market to open the lock so it is their own ‘Aha!’—their own discovery, and so their own commitment.”

Some ads make fun of high-pressure tactics. “Perhaps you’d consider buying one,” says an ad for Saturn, and then in brackets below, “Sorry, we didn’t mean to pressure you like that.” Another car ad declares, “We’re not trying to sell you this car. We’re just letting you know it exists.” An ad for sneakers tells us that “marketing is just hype.” This is a bit like a man unbuttoning a woman’s blouse, all the while telling her that she is far too smart to be seduced by the likes of him.

Cynicism is one of the worst effects of advertising. Cynicism learned from years of being exposed to marketing hype and products that never deliver the promised goods often carries over to other aspects of life. This starts early: A study of children done by researchers at Columbia University in 1975 found that heavy viewing of advertising led to cynicism, not only about advertising, but about life in general. The researchers found that “in most cultures, adolescents have had to deal with social hypocrisy and even with institutionalized lying. But today, TV advertising is stimulating preadolescent children to think about socially accepted hypocrisy. They may be too young to cope with such thoughts without permanently distorting their views of morality, society, and business.” They concluded that “7- to 10-year-olds are strained by the very existence of advertising directed to them.” These jaded children become the young people whose mantra is “whatever,” who admire people like David Letterman (who has made a career out of taking nothing seriously), whose response to almost every experience is “been there, done that,” “duh,” and “do ya think?” Cynicism is not criticism. It is a lot easier than criticism. In fact, easy cynicism is a kind of naivete. We need to be more critical as a culture and less cynical.

Cynicism deeply affects how we define our problems and envision their solutions. Many people exposed to massive doses of advertising both distrust every possible solution and expect a quick fix. There are no quick fixes to the problems our society faces today, but there are solutions to many of them. The first step, as always, is breaking through denial and facing the problems squarely. I believe it was James Baldwin who said, “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.” One of the things we need to face is that we and our children are indeed influenced by advertising.

Although some people, especially advertisers, continue to argue that advertising simply reflects the society, advertising does a great deal more than simply reflect cultural attitudes and values. Even some advertisers admit to this: Rance Crain of Advertising Age said great advertising “plays the tune rather than just dancing to the tune.” Far from being a passive mirror of society, advertising is an effective and pervasive medium of influence and persuasion, and its influence is cumulative, often subtle, and primarily unconscious. Advertising performs much the same function in industrial society as myth performed in ancient and primitive societies. It is both a creator and perpetuator of the dominant attitudes, values, and ideology of the culture, the social norms and myths by which most people govern their behavior. At the very least, advertising helps to create a climate in which certain attitudes and values flourish and others are not reflected at all.

Advertising is not only our physical environment, it is increasingly our spiritual environment as well. By definition, however, it is only interested in materialistic values. When spiritual values or religious images show up in ads, it is only to appropriate them in order to sell us something. Sometimes this is very obvious. Eternity is a perfume by Calvin Klein. Infiniti is an automobile and Hydra Zen a moisturizer. Jesus is a brand of jeans. “See the light,” says an ad for wool, while a face powder ad promises “an enlightening experience” and “absolute heaven.” One car is “born again” and another promises to “energize your soul.” In a full-page ad in Advertising Age, the online service Yahoo! proclaims, “We’ve got 60 million followers. That’s more than some religions,” but goes on to assure readers, “Don’t worry. We’re not a religion.” When Pope John Paul II visited Mexico City in the winter of 1999, he could have seen a smiling image of himself on bags of Sabritas, a popular brand of potato chips, or a giant street sign showing him bowing piously next to a Pepsi logo with a phrase in Spanish that reads, “Mexico Always Faithful.” In the United States, he could have treated himself to pope-on-a-rope soap.

An ad for kosher hot dogs pictures the Bible beside a hot dog with the caption, “If you liked the book, you’ll love the hot dog.” The campaign slogan is, “We answer to a higher authority.” “God bless America,” says a full-page newspaper ad featuring a little boy with his hand over his heart. The copy continues, “Where else can you find one company that offers phone, cable and internet service?” And an ad for garage doors says, “The legendary architect Mies van der Rohe said, ‘God is in the details.’ If that’s so, could these be the pearly gates?”

Sometimes the allusion to the spiritual realm is more subtle, as in the countless alcohol ads featuring the bottle surrounded by a halo of light. Indeed products are often displayed, such as jewelry shining in a store window, as if they were sacred objects. Buy this and your life will be better. Advertising co-opts our sacred symbols and sacred language in order to evoke an immediate emotional response. Neil Postman refers to this as “cultural rape” that leaves us deprived of our most meaningful images.

But advertising’s co-optation of spirituality goes much deeper than this. It is commonplace these days to observe that consumerism has become the religion of our time (with advertising its holy text), but the criticism usually stops short of what is most important, what is at the heart of the comparison. Advertising and religion share a belief in transformation and transcendence, but most religions believe that this requires work and sacrifice. In the world of advertising, enlightenment is achieved instantly by purchasing material goods. As James Twitchell, author of Adcult USA, says, “The Jolly Green Giant, the Michelin Man, the Man from Glad, Mother Nature, Aunt Jemima, Speedy Alka-Seltzer, the White Knight, and all their otherworldly kin are descendants of the earlier gods. What separates them is that they now reside in manufactured products and that, although earlier gods were invoked by fasting, prayer, rituals, and penance, the promise of purchase calls forth their modern ilk.”

Advertising constantly promotes the core belief of American culture: that we can re-create ourselves, transform ourselves, transcend our circumstances—but with a twist. For generations Americans believed this could be achieved if we worked hard enough, like Horatio Alger. Today the promise is that we can change our lives instantly, effortlessly—by winning the lottery, selecting the right mutual fund, having a fashion makeover, losing weight, having tighter abs, buying the right car or soft drink. It is this belief that such transformation is possible that drives us to keep dieting, to buy more stuff, to read fashion magazines that give us the same information over and over again. Cindy Crawford’s makeup is carefully described as if it could transform us into her. On one level, we know it won’t—after all, most of us have tried this approach many times before. But on another level, we continue to try, continue to believe that this time it will be different. This American belief that we can transform ourselves makes advertising images much more powerful than they otherwise would be.

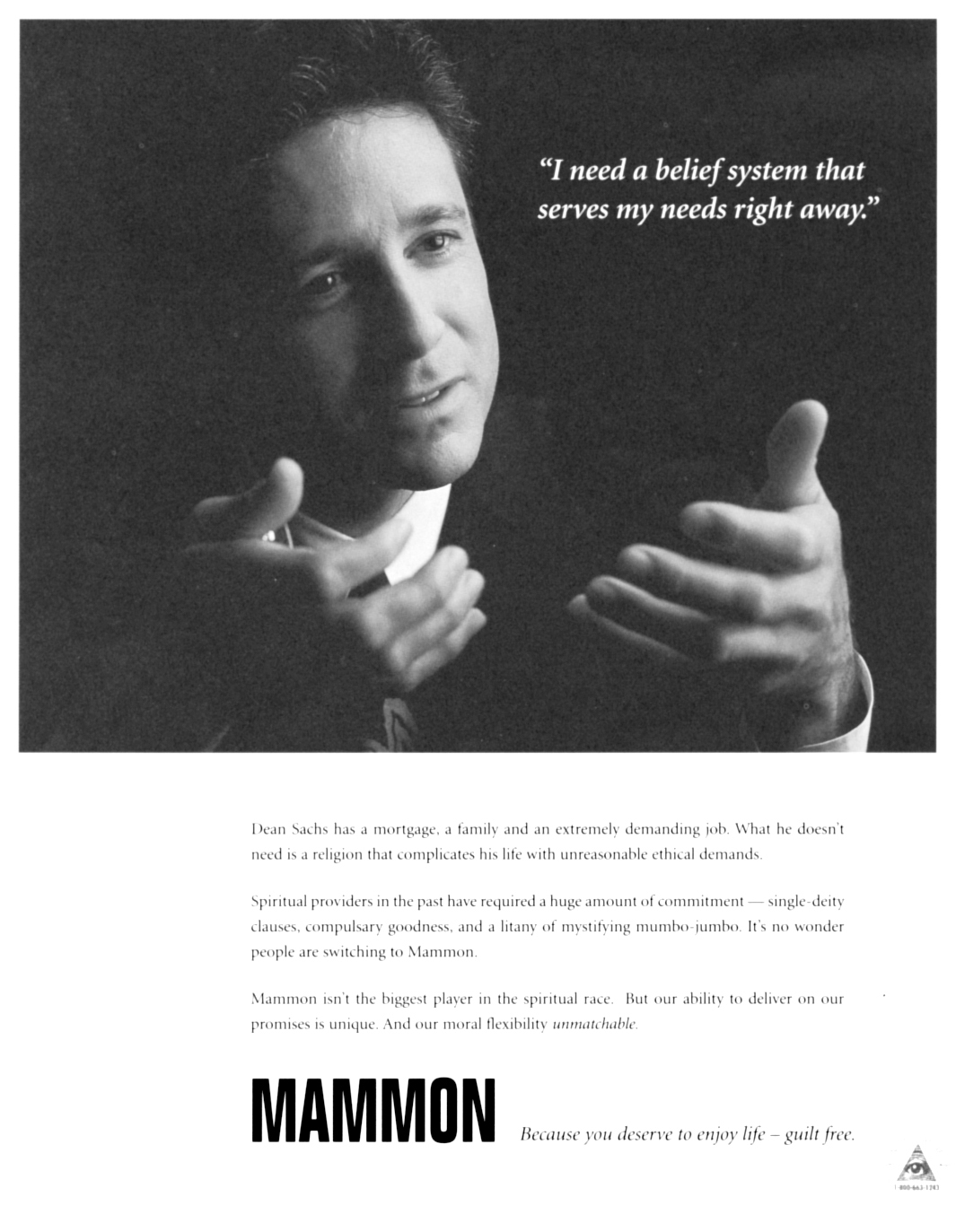

The focus of the transformation has shifted from the soul to the body. Of course, this trivializes and cheapens authentic spirituality and transcendence. But, more important, this junk food for the soul leaves us hungry, empty, malnourished. The emphasis on instant salvation is parodied in an ad from Adbusters for a product called Mammon, in which a man says, “I need a belief system that serves my needs right away.” The copy continues, “Dean Sachs has a mortgage, a family and an extremely demanding job. What he doesn’t need is a religion that complicates his life with unreasonable ethical demands.” The ad ends with the words, “Mammon: Because you deserve to enjoy life—guilt free.”

As advertising becomes more and more absurd, however, it becomes increasingly difficult to parody ads. There’s not much of a difference between the ad for Mammon and the real ad for cruises that says “It can take several lifetimes to reach a state of inner peace and tranquillity. Or, it can take a couple of weeks.” Of course, we know that a couple of weeks on a cruise won’t solve our problems, won’t bring us to a state of peace and enlightenment, but it is so tempting to believe that there is some easy way to get there, some ticket we can buy.

To be one of the “elect” in today’s society is to have enough money to buy luxury goods. Of course, when salvation comes via the sale, it becomes important to display these goods. Owning a Rolex would not impress anyone who didn’t know how expensive it is. A Rolex ad itself says the watch was voted “most likely to be coveted.” Indeed, one of advertising’s purposes is to create an aura for a product, so that other people will be impressed. As one marketer said recently in Advertising Age, “It’s no fun to spend $100 on athletic shoes to wear to high school if your friends don’t know how cool your shoes are.”

Thus the influence of advertising goes way beyond the target audience and includes those who could never afford the product, who will simply be envious and impressed—perhaps to the point of killing someone for his sneakers or jacket, as has sometimes happened in our poverty-stricken neighborhoods. In the early 1990s the city health commissioner in Philadelphia issued a public health warning cautioning youths against wearing expensive leather jackets and jewelry, while in Milwaukee billboards depicted a chalk outline of a body and the warning, “Dress Smart and Stay Alive.” Poor children in many countries knot the laces of their Nikes around their ankles to avoid having them stolen while they sleep.

Many teens fantasize that objects will somehow transform their lives, give them social standing and respect. When they wear a certain brand of sneaker or jacket, they feel, “This is important, therefore I am important.” The brand gives instant status. No wonder they are willing, even eager, to spend money for clothes that advertise the brands. A USA Today-CNN-Gallup Poll found that 61 percent of boys and 44 percent of girls considered brand names on clothes “very important” or “somewhat important.” As ten-year-old Darion Sawyer from Baltimore said, “People will tease you and talk about you, say you got on no-name shoes or say you shop at Kmart.” Leydiana Reyes, an eighth-grader in Brooklyn, said, “My father always tells me I could buy two pairs of jeans for what you pay for Calvin Klein. I know that. But I still want Calvin Klein.” And Danny Shirley, a fourteen-year-old in Santa Fe decked out in Tommy Hilfiger regalia, said, “Kids who wear Levi’s don’t really care about what they wear, I guess.”

In the beginning, these labels were somewhat discreet. Today we see sweatshirts with fifteen-inch “Polo” logos stamped across the chest, jeans with four-inch “Calvin Klein” labels stitched on them, and a jacket with “Tommy Hilfiger” in five-inch letters across the back. Some of these outfits are so close to sandwich boards that I’m surprised people aren’t paid to wear them. Before too long, the logo-free product probably will be the expensive rarity.

What people who wear these clothes are really buying isn’t a garment, of course, but an image. And increasingly, an image is all that advertising has to sell. Advertising began centuries ago with signs in medieval villages. In the nineteenth century, it became more common but was still essentially designed to give people information about manufactured goods and services. Since the 1920s, advertising has provided less information about the product and focused more on the lives, especially the emotional lives, of the prospective consumers. This shift coincided, of course, with the increasing knowledge and acceptability of psychology, as well as the success of propaganda used to convince the population to support World War I.

Industrialization gave rise to the burgeoning ability of businesses to mass-produce goods. Since it was no longer certain there would be a market for the goods, it became necessary not just to mass-produce the goods but to mass-produce markets hungry for the goods. The problem became not too little candy produced but not enough candy consumed, so it became the job of the advertisers to produce consumers. This led to an increased use of psychological research and emotional ploys to sell products. Consumer behavior became recognized as a science in the late 1940s.

As luxury goods, prepared foods, and nonessential items have proliferated, it has become crucial to create artificial needs in order to sell unnecessary products. Was there such a thing as static cling before there were fabric softeners and sprays? An ad for a “lip renewal cream” says, “I never thought of my lips as a problem area until Andrea came up with the solution.”

Most brands in a given category are essentially the same. Most shampoos are made by two or three manufacturers. Blindfolded smokers or beer-drinkers can rarely identify what brand they are smoking or drinking, including their own. Whether we know it or not, we select products primarily because of the image reflected in their advertising. Very few ads give us any real information at all. Sometimes it is impossible to tell what is being advertised. “This is an ad for the hair dryer,” says one ad, featuring a woman lounging on a sofa. If we weren’t told, we would never know. A joke made the rounds a while ago about a little boy who wanted a box of tampons so that he could effortlessly ride bicycles and horses, ski, and swim.

Almost all tobacco and alcohol ads are entirely image-based. Of course, when you’re selling a product that kills people, it’s difficult to give honest information about it. Think of all the cigarette ads that never show cigarettes or even a wisp of smoke. One of the most striking examples of image advertising is the very successful and long-running campaign for Absolut vodka. This campaign focuses on the shape of the bottle and the word “Absolut,” as in “Absolut Perfection,” which features the bottle with a halo. This campaign has been so successful that a coffee-table book collection of the ads published just in time for Christmas, the perfect gift for the alcoholic in your family, sold over 150,000 copies. Collecting Absolut ads is now a common pastime for elementary-school children, who swap them like baseball cards.

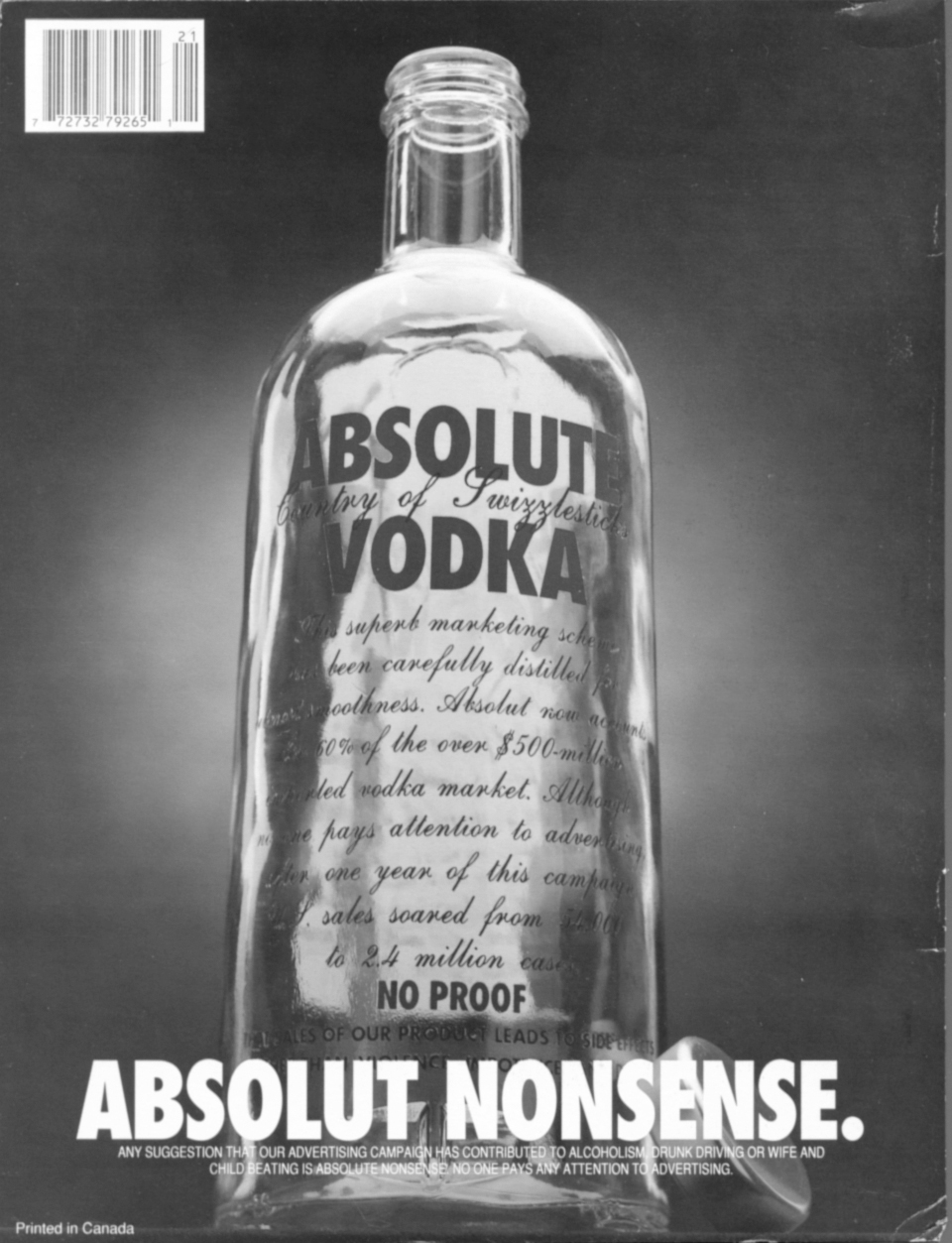

Adbusters magazine often parodies the Absolut ads. One such parody, headlined “Absolut Nonsense,” pictures a bottle with the following copy on the label: “This superb marketing scheme has been carefully distilled for smoothness.… Although no one pays attention to advertising, after one year of this campaign, sales soared from 54,000 cases to 2.4 million cases.” Since all vodka is essentially the same, all the campaign can sell us is image.

Even the advertisers admit to this. Carol Nathanson-Moog, an advertising psychologist, said, “More and more it seems the liquor industry has awakened to the truth. It isn’t selling bottles or glasses or even liquor. It’s selling fantasies.” An article in Advertising Age went further, stating that “product image is probably the most important element in selling liquor. The trick for marketers is to project the right message in their advertisements to motivate those often motionless consumers to march down to the liquor store or bar and exchange their money for a sip of image.”

“A sip of image.” Just as simple films relying on crude jokes and violence are perfect for the global marketplace, since they require little translation, so is advertising that relies entirely on image. Bare breasts and phallic symbols are understood everywhere. As are the nude female buttocks featured in the Italian and German ads for similar worthless products to remedy the imaginary problem of cellulite. Unfortunately, such powerful imagery often pollutes the cultural environment. Certainly this is so with the Olivetti ad that ran in a Russian publication. In case the image is too subtle for some, the copy says “Fax me.” Sexism in advertising, although increasingly recognized as a problem, remains an ongoing global issue.

How does all this affect us? It is very difficult to do objective research about advertising’s influence because there are no comparison groups, almost no people who have not been exposed to massive doses of advertising. In addition, research that measures only one point in time does not adequately capture advertising’s real effects. We need longitudinal studies, such as George Gerbner’s twenty-five-year study of violence on television.

The advertising industry itself can’t prove that advertising works. While claiming to its clients that it does, it simultaneously denies it to the Federal Trade Commission whenever the subject of alcohol and tobacco advertising comes up. As an editorial in Advertising Age once said, “A strange world it is, in which people spending millions on advertising must do their best to prove that advertising doesn’t do very much!” According to Bob Wehling, senior vice-president of marketing at Procter & Gamble, “We don’t have a lot of scientific studies to support our belief that advertising works. But we have seen that the power of advertising makes a significant difference.”

What research can most easily prove is usually what is least important, such as advertising’s influence on our choice of brands. This is the most obvious, but least significant, way that advertising affects us. There are countless examples of successful advertising campaigns, such as the Absolut campaign, that have sent sales soaring. A commercial for I Can’t Believe It’s Not Butter featuring a sculptress whose work comes alive in the form of romance-novel hunk Fabio boosted sales about 17 percent. Tamagotchis—virtual pets in an egg—were introduced in the United States with a massive advertising campaign and earned $150 million in seven months. And Gardenburger, a veggie patty, ran a thirty-second spot during the final episode of Seinfeld and, within a week, sold over $2 million worth, a market share jump of 50 percent and more than the entire category sold in the same week the previous year. But advertising is more of an art than a science, and campaigns often fail. In 1998 a Miller beer campaign bombed, costing the company millions of dollars and offending a large segment of their customers. The 1989 Nissan Infiniti campaign, known as the “Rocks and Trees” campaign, was the first ever to introduce a car without showing it and immediately became a target for Jay Leno’s monologues. And, of course, the Edsel, a car introduced by Ford with great fanfare in 1957, remains a universal symbol of failure.

The unintended effects of advertising are far more important and far more difficult to measure than those effects that are intended. The important question is not “Does this ad sell the product?” but rather “What else does this ad sell?” An ad for Gap khakis featuring a group of acrobatic swing dancers probably sold a lot of pants, which, of course, was the intention of the advertisers. But it also contributed to a rage for swing dancing. This is an innocuous example of advertising’s powerful unintended effects. Swing dancing is not binge drinking, after all.

Advertising often sells a great deal more than products. It sells values, images, and concepts of love and sexuality, romance, success, and, perhaps most important, normalcy. To a great extent, it tells us who we are and who we should be. We are increasingly using brand names to create our identities. James Twitchell argues that the label of our shirt, the make of our car, and our favorite laundry detergent are filling the vacuum once occupied by religion, education, and our family name.

Even more important, advertising corrupts our language and thus influences our ability to think clearly. Critic and novelist George Steiner once talked with an interviewer about what he called “anti-language, that which is transcendentally annihilating of truth and meaning.” Novelist Jonathan Dee, applying this concept to advertising, writes that “the harm lies not in the ad itself; the harm is in the exchange, in the collision of ad language, ad imagery, with other sorts of language that contend with it in the public realm. When Apple reprints an old photo of Gandhi, or Heineken ends its ads with the words ‘Seek the Truth,’ or Winston suggests that we buy cigarettes by proposing (just under the surgeon general’s warning) that ‘You have to appreciate authenticity in all its forms,’ or Kellogg’s identifies itself with the message ‘Simple is Good,’ these occasions color our contact with those words and images in their other, possibly less promotional applications.” The real violence of advertising, Dee concludes, is that “words can be made to mean anything, which is hard to distinguish from the idea that words mean nothing.” We see the consequences of this in much of our culture, from “art” to politics, that has no content, no connection between language and conviction. Just as it is often difficult to tell what product an ad is selling, so is it difficult to determine what a politician’s beliefs are (the “vision thing,” as George Bush so aptly called it, albeit unintentionally) or what the subject is of a film or song or work of art. As Dee says, “The men and women who make ads are not hucksters; they are artists with nothing to say, and they have found their form.” Unfortunately, their form deeply influences all the other forms of the culture. We end up expecting nothing more.

This has terrible consequences for our culture. As Richard Pollay says, “Without a reliance on words and a faith in truth, we lack the mortar for social cohesion. Without trustworthy communication, there is no communion, no community, only an aggregation of increasingly isolated individuals, alone in the mass.”

Advertising creates a worldview that is based upon cynicism, dissatisfaction, and craving. The advertisers aren’t evil. They are just doing their job, which is to sell a product, but the consequences, usually unintended, are often destructive to individuals, to cultures, and to the planet. In the history of the world, there has never been a propaganda effort to match that of advertising in the twentieth century. More thought, more effort, and more money go into advertising than has gone into any other campaign to change social consciousness. The story that advertising tells is that the way to be happy, to find satisfaction—and the path to political freedom, as well—is through the consumption of material objects. And the major motivating force for social change throughout the world today is this belief that happiness comes from the market.

So, advertising has a greater impact on all of us than we generally realize. The primary purpose of the mass media is to deliver us to advertisers. Much of the information that we need from the media in order to make informed choices in our lives is distorted or deleted on behalf of corporate sponsors. Advertising is an increasingly ubiquitous presence in our lives, and it sells much more than products. We delude ourselves when we say we are not influenced by advertising. And we trivialize and ignore its growing significance at our peril.