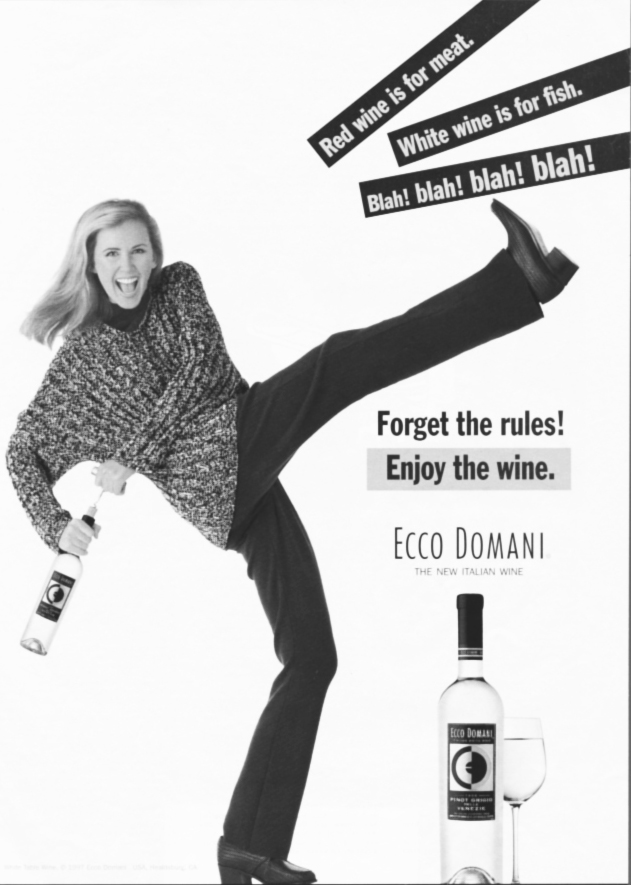

“FORGET THE RULES! ENJOY THE WINE”

Alcohol and Rebellion

![]()

THE NUMBER-ONE ILLEGAL DRUG IN AMERICA IS . . . BEER. BECAUSE BEER IS the drug of choice for young people. Although we hear a lot about marijuana, cocaine, and heroin, the truth is our children are at much greater risk from alcohol than from these other drugs. A 1999 study found that almost 8 percent of nine-year-olds are already drinking beer. Fifteen percent of eighth-graders and 30 percent of twelfth-graders are binge drinkers, which means they’ve had five or more drinks at one sitting within the past two weeks. In college, the percentage of binge drinkers rises to 45 percent.

What are the risks of this drinking? One risk is death. Alcohol is the leading killer of young people in America—because it is a major factor in the three main causes of death for people between the ages of fifteen and twenty-four, which are automobile crashes, homicide, and suicide. Alcohol is also linked with over half of all violent crimes, domestic violence, rape, and child abuse.

Another risk is addiction. The younger people are when they start to drink, the greater the risk of addiction, by far. People who start drinking by the age of fifteen are four times more likely to become addicted than those who wait until they are twenty-one. According to Dr. Bernadine Healey, “Exposure of the adolescent brain to alcohol appears to predispose a person to alcohol abuse and alcoholism in later life.” Now this is bad news for most of us, but it’s good news for the alcohol industry. Just as the tobacco industry and the food industry depend on addicts for their profits, so does the alcohol industry.

Ten percent of drinkers consume over 60 percent of all the alcohol sold. At least one in ten drinkers is an alcoholic. You don’t have to be a mathematical genius to figure out that the alcoholic is the alcohol industry’s best customer. Although the industry says it wants people to drink “responsibly,” the truth is that so-called responsible drinking would put it out of business. As August Busch III, the CEO of Anheuser Busch, said in the company’s annual report, “Every action taken by your company’s management is guided by one overriding objective—enhancing shareholder value.” In plain language, this means to sell as much beer as possible. Of course, this is true for any business—but when the product is alcohol, there are often tragic consequences.

If alcoholics were to stop drinking entirely, the industry would lose over half its profits. In fact, if every adult American drank at the “safe” level according to federal guidelines, which is no more than one drink a day for a woman and two drinks a day for a man, alcohol industry sales would be cut by about 80 percent. As one researcher said, “Though problem-free drinking does exist for great numbers of people, it is at such picayune levels that it would sustain only a fraction of the present alcoholic beverage industry.”

It is not only alcoholics who are doing the heavy drinking—and causing the resulting problems. Thomas Greenfield of the Alcohol Research Group pooled extensive data from the United States and Canada that provided a disturbing picture of the drinking practices of young adults. Overall, the data show that 43 percent of all alcohol consumed is consumed hazardously (defined, as is binge drinking, as five or more drinks in a single sitting). However, among young adults (defined as from eighteen to thirty-nine), nearly 80 percent is consumed hazardously. Some of these people are alcoholics, of course, but many are not. Indeed it is the heavy drinkers who are not alcoholic who cause the most problems in the society, simply because there are so many more of them.

Obviously, the young people who are consuming five or more drinks in a sitting (and often causing terrible problems for themselves and the people around them) are extremely desirable to the alcohol industry. The ones who are or become alcoholic are even more desirable. The top 2.5 percent of drinkers average nine drinks a day and consume a third of all alcohol sold. Sixty-three percent of this group is eighteen to twenty-nine years old (although they make up just 27 percent of the total population). Just as the tobacco industry needs to get kids addicted in order to be sure of a fresh supply of addicts, so does the alcohol industry. Sometimes these industries are one and the same. Philip Morris, maker of Virginia Slims and Marlboros, also owns Miller beer, the number-two beer in the country. Both the alcohol and tobacco industries are in the business of recruiting new users. Of course, this means targeting children. Hook them early and they are yours for life. These young people spend a lot of money in the present on alcohol too: According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, junior and senior high-school students drink over a billion cans of beer a year, spending almost $500 million.

What’s the best way to appeal to young people? One way, of course, is to present the product as strictly for adults—as in the so-called moderation messages of the alcohol and tobacco industries. Don’t drink or smoke, they say—that’s for grown-ups (a great way to make sure kids never touch the stuff!). Another ploy is to use cute little animals and cartoon characters—like Spuds MacKenzie and the Budweiser frogs, lizards, and dalmatians. Joe Camel has been sent out to pasture, but Budweiser’s lethal creatures are still very much with us. Children also find these advertising icons on shirts, hats, mugs, stuffed animals, and other paraphernalia.

Budweiser, the King of Drugs, is the most widely used and widely advertised beer by far. Anheuser-Busch, the largest brewer in the world and the maker of Budweiser, supplies almost one-fourth of all the alcohol that Americans consume and spends over a quarter of a billion dollars a year on advertising and promotion. Of course, they deny that this advertising attracts young people. According to one vice-president, “We do not target our advertising toward young people. Period.” A look at some of their ads reveals a different story.

Anheuser-Busch has used many different animals in its campaigns over the years, beginning with Clydesdale horses. As one Anheuser-Busch marketing executive said, “Fifty years ago, Clydesdales were just horses. Now it is impossible for people to see them and not think of Budweiser.” The horses have been followed by ants, alligators, penguins, frogs, lizards, and the bull terrier Spuds MacKenzie. These images are especially alluring to children, because most children have a special affinity with animals. They have relationships with creatures, becoming deeply attached to stuffed animals and cartoon characters as well as to real ones.

The Budweiser frogs are especially appealing to children. Introduced during the 1995 Super Bowl to an audience of more than 40 million viewers, a fair share of whom were under the legal drinking age, this campaign featured three frogs chirping Bud-weis-er. One critic described it as “nothing but a phonics lesson for five-year-olds.” The frogs have been criticized by a slew of consumer advocate groups and health associations such as the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Public Health Association, which claim the ads deliberately target children and are the alcohol industry’s version of Joe Camel. Frank and Louie, the sardonic lizards who have taken over the frogs’ job, have also taken over their number-one spot in children’s hearts and minds.

Anheuser-Busch also designs products with special appeal to children. According to Supermarket News, longneck bottles of Bud Ice and Bud Ice Light will soon be coming with Bud Iceicles, colored flavors to be added to the beer. The flavors, clearly intended for grown-ups, include Dooby-Dooby Doo, Kiss My Ice, and Loose Juice. Maybe next Bud will have Barney, dancing and singing, “I love you, you love me, grab a Bud and let’s party.”

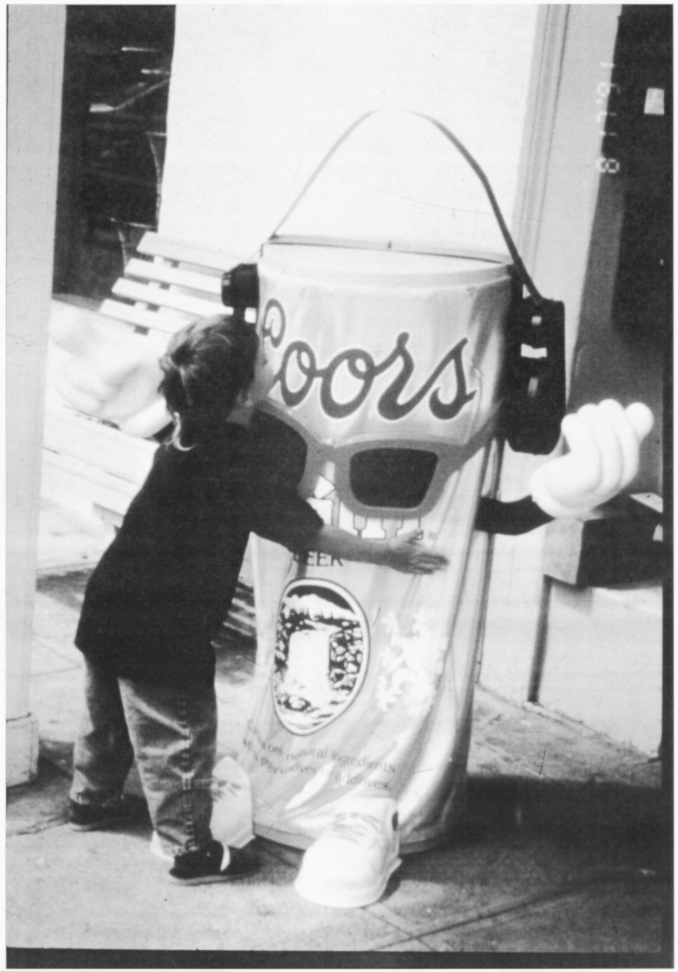

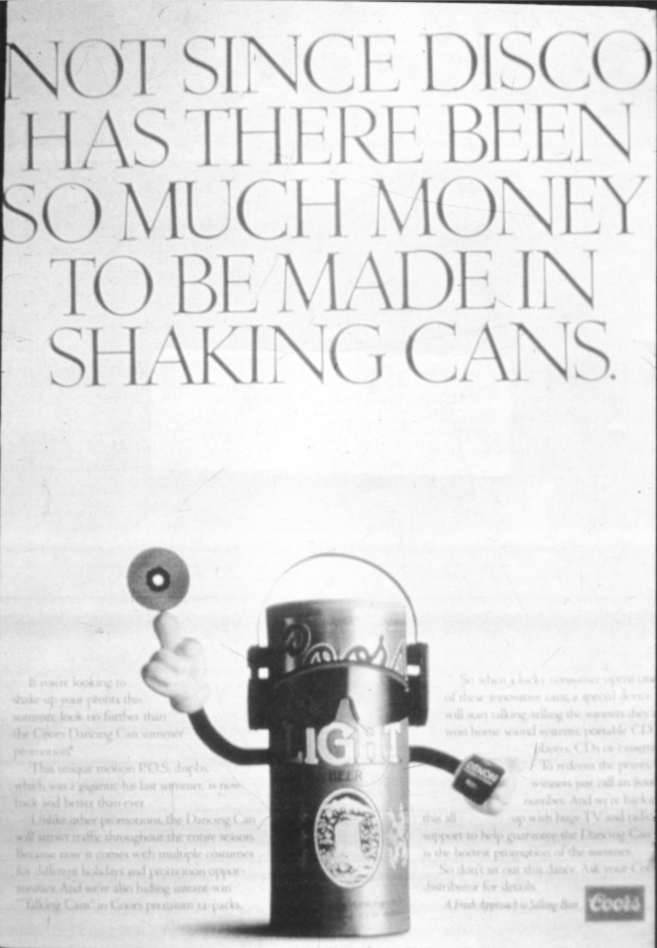

Of course, Bud is not alone. Most brewers target young people. A 1994 Coors promotion featured people dressed as beer cans dancing in public places and liquor stores. They seemed to be as appealing to children as Mickey Mouse at Disneyland. As one liquor store owner said, “The dancing can from Coors was one of the best [point-of-sale materials], little kids were dragging their parents into the store to see it.” An ad placed by Coors in a trade publication said, “Not since disco has there been so much money to be made in shaking cans.”

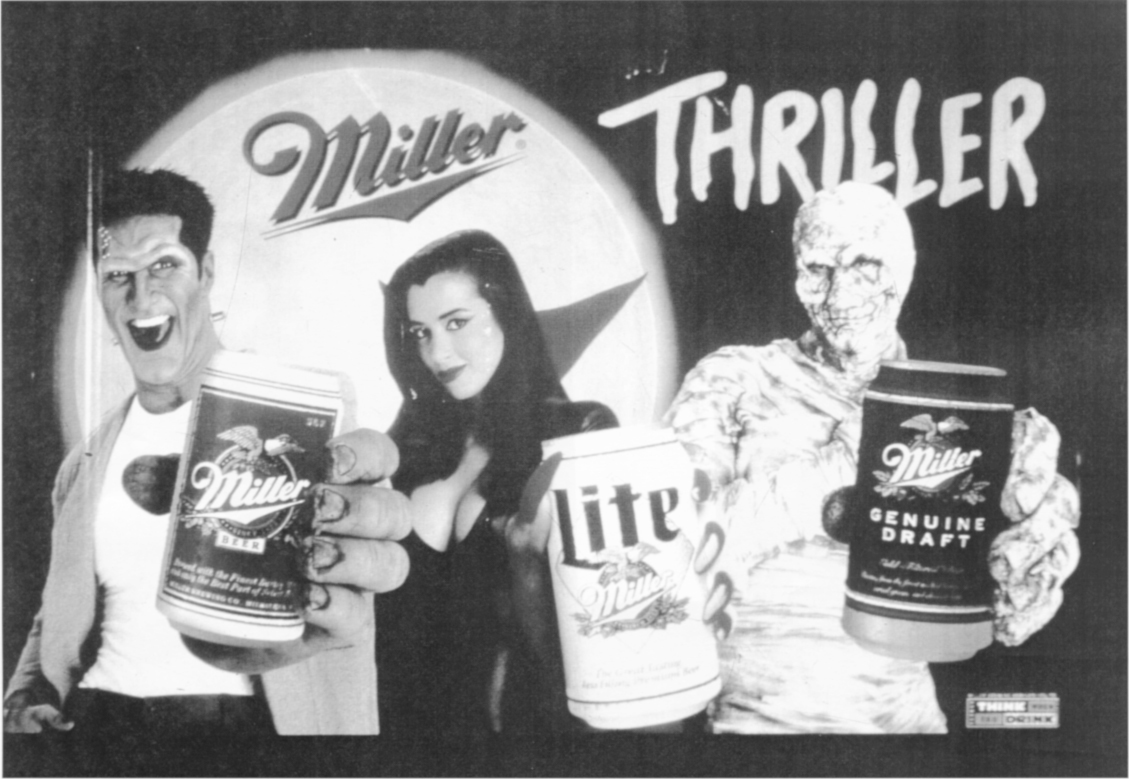

All the major brewers have been involved in the campaign to turn Halloween into what a Coors executive calls “a beer-guzzling holiday.” “Miller Thriller,” says one ad, featuring an assortment of monsters offering beer cans. “I want your Bud,” says a vampire in a Budweiser ad. According to a Coors’ marketing executive, “We invented Halloween and we intend to keep it.”

Do these ads affect children? Children certainly notice them: the Budweiser frog campaign is the most popular of all among children over the age of six—more popular than commercials for McDonald’s, Pepsi, or Nike. According to a 1996 survey by the Center on Alcohol Advertising, almost as many children between the ages of nine and eleven know that frogs say “Budweiser” (73 percent) as know that Bugs Bunny says “What’s up, Doc?” (80 percent). Laurie Leiber, the center’s director, said, “After a single year of advertising, the Budweiser frogs have assumed a friendly place in our children’s psyches between Bugs Bunny and Smokey the Bear.”

A survey of eight- to twelve-year-olds in Washington, D.C., found that students could name more brands of beer than they could U.S. presidents. And a 1998 study, conducted by the ad agency Campbell Mithun Esty, found that most children liked the Budweiser lizard ads better than ads for Barbie (of course, this might not be such a bad thing). The advertising industry claims that the appeal of these ads to children is unintentional. As Bob Garfield, ad reviewer for Advertising Age, says, “Advertising is not a rifle; it is a shotgun, and any campaign featuring outdoor boards of a cartoon animal inevitably will catch children in its spray.” In a different column, however, Garfield also acknowledges that a cartoon is “all it takes to be irresistible to children.”

I don’t think the alcohol industry wants little children to drink. However, they do want them to have positive associations with alcohol, and with specific brands of alcohol, long before they start to drink. This is a basic function of advertising. A 1919 article in Printer’s Ink, an advertising industry publication, makes this explicit: “It requires much brain work and close study to advertise to children in the best way to sell them things that childhood craves, such as toys, but this is nothing compared to the selling of products they cannot have until they are grown up—to make boys and girls want things now they couldn’t have and shouldn’t have for five, ten or twenty years. Some advertisers see little sense in spending money advertising ‘grown-up goods’ to children; many, however, have found out the wisdom and profit in doing it.” Using the example of automobile advertising, the article stresses the importance of getting a particular brand name to replace the general category of “automobile” early in a child’s life. If the advertiser waits until the child has grown up, it is too late: “The waxlike mind would be crisscrossed by other names; the soil would have other seeds beside his and it would be a continual struggle for supremacy. First impressions are strong—which is particularly true of advertised goods.” Many years later, an editorial in Advertising Age reached the same conclusion: “Quite clearly, the company that has not bothered to create a favorable attitude toward its product before the potential customer goes shopping hasn’t much of a chance of snaring the bulk of potential buyers.”

Could this be any less true for alcohol than for other products? After all, the average age at which American children start to drink these days is twelve. It’s almost never too soon to reach them. It’s an investment in the future. As one marketing executive said about the importance of developing brand loyalty in a college student, “If he turns out to be a big drinker, the beer company has bought itself an annuity.”

Although it is difficult, if not impossible, to measure the exact influence of advertising, various research studies have shown that alcohol advertising shapes young adolescents’ attitudes and intentions about alcohol and creates an unconscious presumption in favor of drinking. This unconscious presumption is extremely important. According to the Seventh Special Report to the U.S. Congress on Alcohol and Health, “People can acquire expectations about alcohol long before they take their first drink and these early expectancies are strong predictors of drinking behavior in adolescence as well as of alcohol dependence in adulthood.” Although behavior reflecting the impact of alcohol advertising may not occur for months or years after exposure, it is obviously very important for the alcohol industry to get ’em while they’re young.

So the brewers broadcast their ads on cable television during youth viewing hours, and on shows such as Beavis and Butthead, whose audiences are predominantly underage. Despite their denials, leading brewers have run commercials on MTV during time periods when half or more of the audience was below the legal drinking age. Both Budweiser and Miller, along with makers of distilled spirits, sponsor the “extreme” sports that especially appeal to young people, such as snowboarding, mountain biking, and in-line skating, and sell sports paraphernalia with the brand logo through marketing campaigns like Budweiser’s “Buy the Beer, Get the Gear.” According to a Jose Cuervo tequila spokesperson, “It’s essential to our brand image to sponsor the boldest, most surprising stuff because our audience is young and rebellious and that’s how they know us.”

The alcohol industry also reaches young people via magazines such as Spin and Allure, with almost half of their readers under twenty-one, and via flashy Websites on the Internet. In 1998 the Center for Media Education found that 82 percent of beer websites and 72 percent of distilled spirits sites used techniques that are particularly attractive to underage audiences (compared with only 10 percent of wine sites). At Absolutvodka.com, Web surfers are greeted by a drum-beating rhythm. As they move their cursors, video clips featuring trendy rock bands appear and the sound level booms. At the site for Captain Morgan’s rum, visitors can watch a comedy show. Cuervo tequila offers a cartoon rodent starring in an animated game, while the Miller beer site offers a monthly magazine focused on fashion, music, and sports. These sites are often called up by searches for “games,” “entertainment,” “music,” “contests,” and “Halloween.” Children trying to learn more about “frogs” on the Internet could conceivably find themselves at the Budweiser site, where animated frogs like to “hang on the beach with a hot babe, a cold Bud and . . . the Kama Sutra.”

In recent years the alcohol industry has developed several new products that seem expressly designed for young people. This trend began with the introduction in 1984 of wine coolers—very sweet, carbonated wine drinks that were marketed as if they were soft drinks. They are often positioned as alternatives to nonalcoholic beverages rather than as alternatives to other forms of alcohol. As one wine cooler ad said, “Sick of soft drinks? Here’s Thirst Aid.” Unlike beer and hard liquor, one doesn’t have to develop a taste for them. According to Advertising Age, “One might say that this product, due to its sweet, cold and refreshing nature, appeals to the ‘Pepsi generation.’” Wine coolers quickly became an over $2-billion-a-year industry. Junior and senior high-school students drink over 35 percent of all the wine coolers sold in the United States.

This success led to products targeting kids that mixed alcohol with ice cream, milk, Jell-O, popsicles, and punch, among other things. This marketing strategy began in Britain, where alcoholic “soft drinks” called Hooper’s Hooch Alcoholic Lemonade, Cola Lips Alcoholic Cola, and Mrs. Pucker’s Alcoholic Orangeade have found great success with young people. In 1995 the Royal College of Physicians issued a report condemning this “cynical marketing ploy to encourage young people to drink” and calling alcohol “ten times more dangerous to the health of young people than illicit drugs.”

It didn’t take long for the United States and other countries to catch up. “The hottest new drink trend,” proclaims an ad in a trade publication for Slushies, drinks that mix alcohol and fruit slush. Tumblers is a twenty-four-proof version of Jell-O shots and Tooters are thirty-proof, neon-colored shots packaged together in test tubes. And tequila aficionados can buy lollipops complete with real worms inside. In 1996 T.G.I. Friday’s, the restaurant chain, introduced small bottles of drinks made by Heublein containing 15 to 20 percent alcohol, with cartoons on the label and names such as Butter Ball, Oatmeal Cookie, and Lemon Drop. The chain claimed these products were aimed at men over thirty. In the beginning, advertising was limited to in-store displays and samples passed out at rock concerts.

Blenders, an ice cream product laced with alcohol and liqueurs sold in little cups for ninety-nine cents, is referred to by its makers as an “adult dessert.” Flavors include Strawberry Shortcake, Chocolate Monkey, and Rootbeer Float. The label features the silhouette of a small child with a line drawn through it, which certainly should keep kids away. A full-page ad for Tattoo, by Jim Beam Brands, offers “the new shot sensation that leaves more than a great taste in your mouth.” The product, which is 30 percent alcohol, comes in three flavors—lemon, berry, and red licorice—and colors the drinker’s tongue. Promotional merchandise includes T-shirts and temporary tattoos.

Moo and Super Milch are flavored milk drinks with an alcohol content of 5 percent, sold in supermarkets as well as in liquor stores. Liquor Pops, a popsicle with an alcohol content of 6 percent, went on sale in Australia early in 1999, in spite of protests from parent and church groups. And Australian company Candyco is test-marketing a product called Candy Shots, a 28 percent alcohol vodkabased drink that comes in flavors like banana, marshmallow, chocolate, and caramel. The drink’s advertising poster depicts a bottle filled with candy. The alcohol industry sometimes refers to such products as “entry-level” drinks.

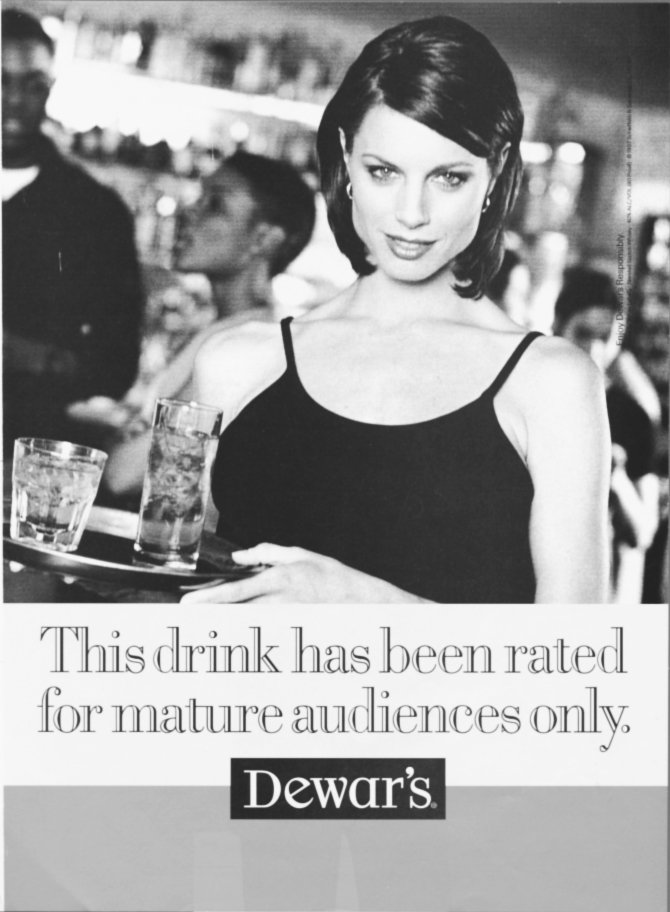

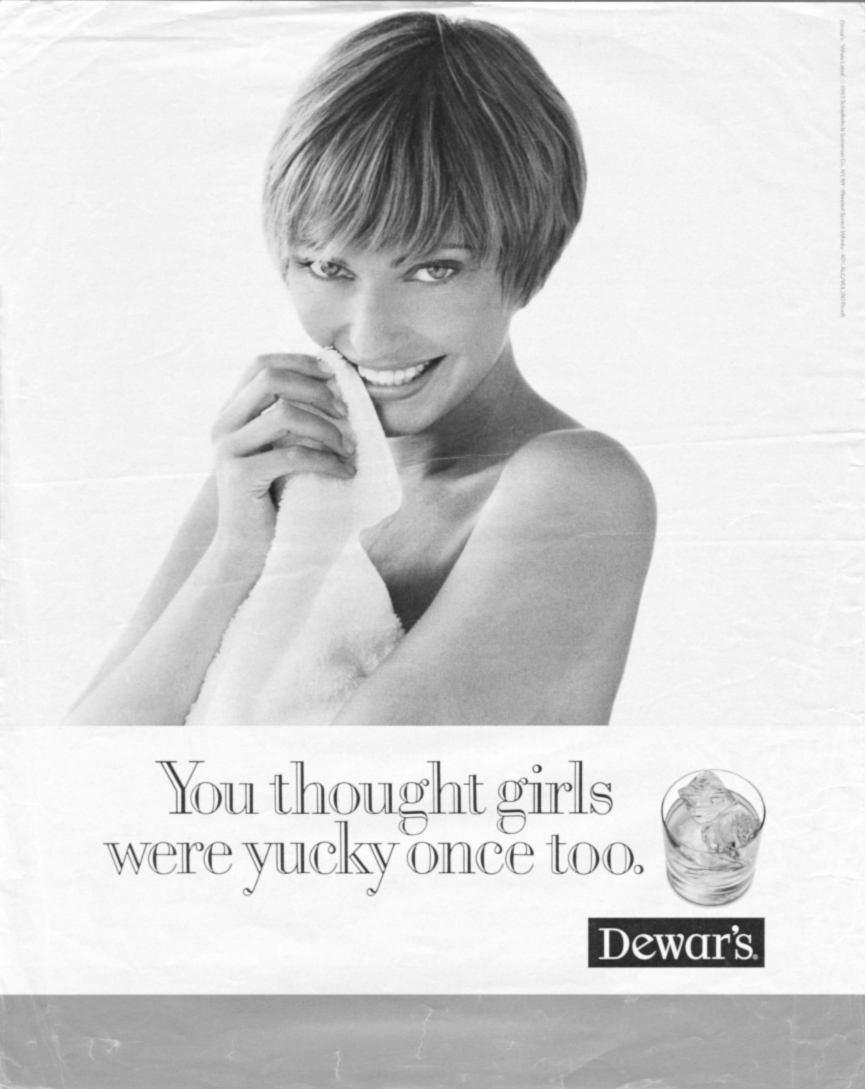

The distilled spirits industry wants its share of the youth market too, of course, but it has a hard time competing with the beer industry. One of its ploys is to offer hard liquor as the grown-up drink, what one “graduates” to after one’s childish beer-drinking days. “You thought girls were yucky once too,” says an ad for Dewar’s scotch. Of course, most boys become interested in girls long before they reach the legal drinking age. “Your taste in music isn’t the only thing changing,” says another ad in this campaign, featuring a photo of a heavy metal musician guaranteed to get the attention of very young men. Another ad offers the scotch in more explicit competition with beer, with a photo of an attractive young couple and the headline, “Now that you understand splitting a 6-pack under the bleachers is no longer considered a date.”

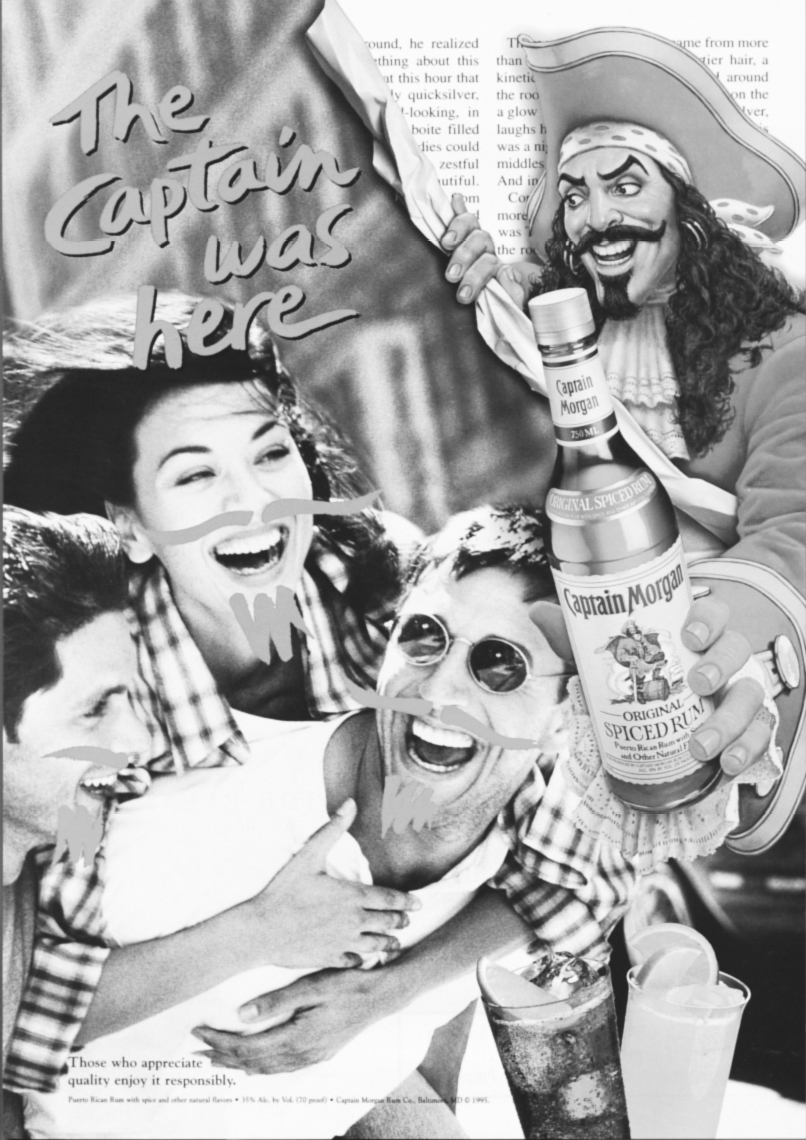

Other distilled spirits ads also use images that will catch the attention of young people, such as a Captain Morgan rum ad featuring a cartoon pirate and young people with bright red beards and mustaches sketched on their faces. Peachtree suggests that their liqueur “jazzes ginger ale” and Bacardi promises to “spice things up around here” by replacing the predictable beer.

In addition to targeting young people in general, the alcohol industry also specifically targets young members of minority groups. A Budweiser ad features a man with “k.o.b,” standing for King of Beers, designed on his head in the style often favored by young African-Americans. These young men are especially targeted by the makers of malt liquor, which is usually promoted in a forty-ounce size with the promise of a higher alcohol content and thus more bang for the buck. Rapper King Tee sings in one commercial, “I usually drink it when I’m out just clowning, me and the home boys, you know, be like downing it . . . I grab me a forty when I want to act a fool.” Phat Boy, a malt liquor sold in forty-ounce bottles, is advertised to young urban African-American men with the slogan, “The new malt liquor with an attitude.”

In 1997 protests by public health advocates led McKenzie River, makers of St. Ides, to discontinue their latest product, Special Brew Freeze and Squeeze, a frozen fruit-flavored drink with 6 percent alcohol content, meant to be placed in supermarket freezers next to ice cream and popsicles, predominantly in African-American urban communities—where alcohol abuse is the leading health and safety problem. Although African-Americans drink less per capita than whites, poverty and poor health contribute to disproportionately high rates of alcohol-related disease.

The alcohol industry is also very interested in college students, who tend to drink more than their peers who don’t go to college. For decades alcohol has been wreaking havoc on college campuses, with little attention paid. When I started lecturing on alcohol advertising on college campuses in the 1970s, the brewers ruled. Budweiser, Miller, and Coors had booths at all the conferences attended by college students and gave out free beer and posters. At one convention I attended, young women in short shorts roller-skated through the convention hall, offering free beer to students. I was on one campus where the administration sponsored a chug-a-lug contest—and on several where the only beverage available at the reception following my lecture was alcohol.

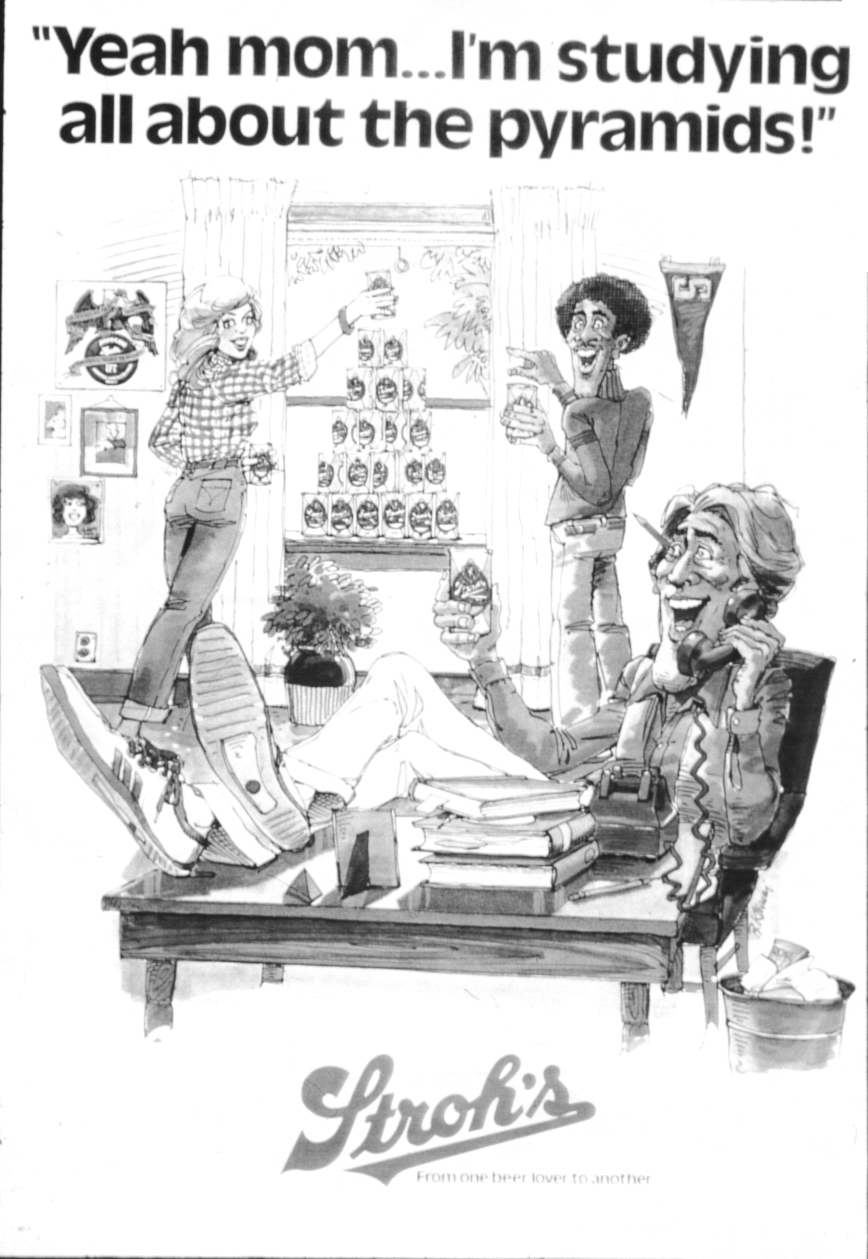

Many ads and posters, especially those for Spring Break, quite explicitly promoted binge drinking and outrageous behavior. “The elephant is now wild on campus,” said a malt liquor ad, while a poster for Stroh’s beer depicted a goofy-looking guy stacking beer cans while saying to his mother on the phone, “Yeah, Mom. . . . I’m studying all about the pyramids.” “Freshmen wait for the weekend to have a Michelob,” said another beer ad. “Seniors know better.” The truth is that seniors drink less than freshmen, because heavy drinking is a behavior one tends to outgrow (unless one is addicted, of course).

Even as late as 1989, Miller inserted into college newspapers, throughout the country, a sixteen-page “comic-book” about the adventures of a college student on spring break named Van Go-Go. From early in the morning until late at night, Van Go-Go drank beer, partied, and “scammed babes.” Many students, upset by this campaign because of the exploitation of women and because it was so moronic, protested, and Miller eventually withdrew the campaign and apologized. However, it is clear that Miller wanted college students to think of Van Go-Go’s drinking as normal. In fact, he was drinking in a very high-risk way and was likely to die from acute alcohol poisoning . . . but, on the other hand, he was spending a fortune on beer.

College students spend $4 billion a year on alcohol, more money than they spend on books. And they drink more than their noncollege peers. No wonder they are so attractive to alcohol advertisers. And no wonder drinking causes so many problems for them. Over half of all cases of violent crime, including rape, on college campuses are alcohol related, as is almost all of the vandalism. Almost all of these crimes are committed by men. The young women who are drinking heavily are more likely to be the victims of assault and to harm themselves. Of students in college in America today, the same percentage will eventually die from alcohol-related causes as will get advanced degrees.

According to Henry Wechsler of the Harvard School of Public Health, although fewer college students are consuming alcohol, those who do drink are consuming more than ever before. In his 1997 study he found that the percentage of students who reported drinking to “get drunk” had increased from 39.4 percent in 1993 to 52.3 percent. Increased drunkenness leads to more problems, of course, both for the drinkers and for those around them.

Binge drinking on college campuses has been front-page news recently, in the wake of several tragic deaths. The coverage began with the death of Scott Krueger, an MIT student who died after having twenty-four drinks in one night as part of a fraternity hazing. Five students died on the morning of their graduation from the University of North Carolina, where students partied with deadly amounts of alcohol. Virginia Tech’s Mindy Somers fell out of a dormitory window while intoxicated, and Leslie Baltz, a University of Virginia senior, died after falling down a flight of stairs. Bradley McCue, a junior at Michigan State University, celebrated his twenty-first birthday by drinking twenty-four shots in ninety minutes and died later that night. In February of 1999, Nicholas Armstrong was beaten to death while he slept off a bender in his fraternity house. Jeremiah Wilkerson, the young man responsible, shot himself, apparently as soon as he sobered up and realized what he had done.

In 1988, after football star Don Rogers and college basketball sensation Len Bias died within a week of each other from cocaine overdoses, the president of the United States declared “war” on illegal drugs and Congress soon agreed to a $1 billion media blitz commanded by a retired general, drug czar Barry McCaffrey. There were at least thirty-four alcohol-related deaths on college campuses in 1998, which only hints at the number of students injured, assaulted, or raped because they or someone else drank too much. But the government didn’t declare war on booze. Instead, the secretary of health and human services asked colleges to adopt voluntary restrictions on alcohol advertising.

Because of increasing scrutiny and the change in the drinking age from eighteen to twenty-one, the alcohol industry has become more subtle in its direct targeting of college students. But their clever, youth-oriented commercials and promotions still reach college students, of course, who often decorate their dorms and fraternity houses with Absolut ads and beer posters. And local bars promote heavy drinking through ads in student newspapers saying such things as “Why wet your whistle when you can drown it?” and offering “Chug-a-mug $1.25 liter drafts!” “$1 Kamikazes all night long,” and “Bucket o’liquor $3!”

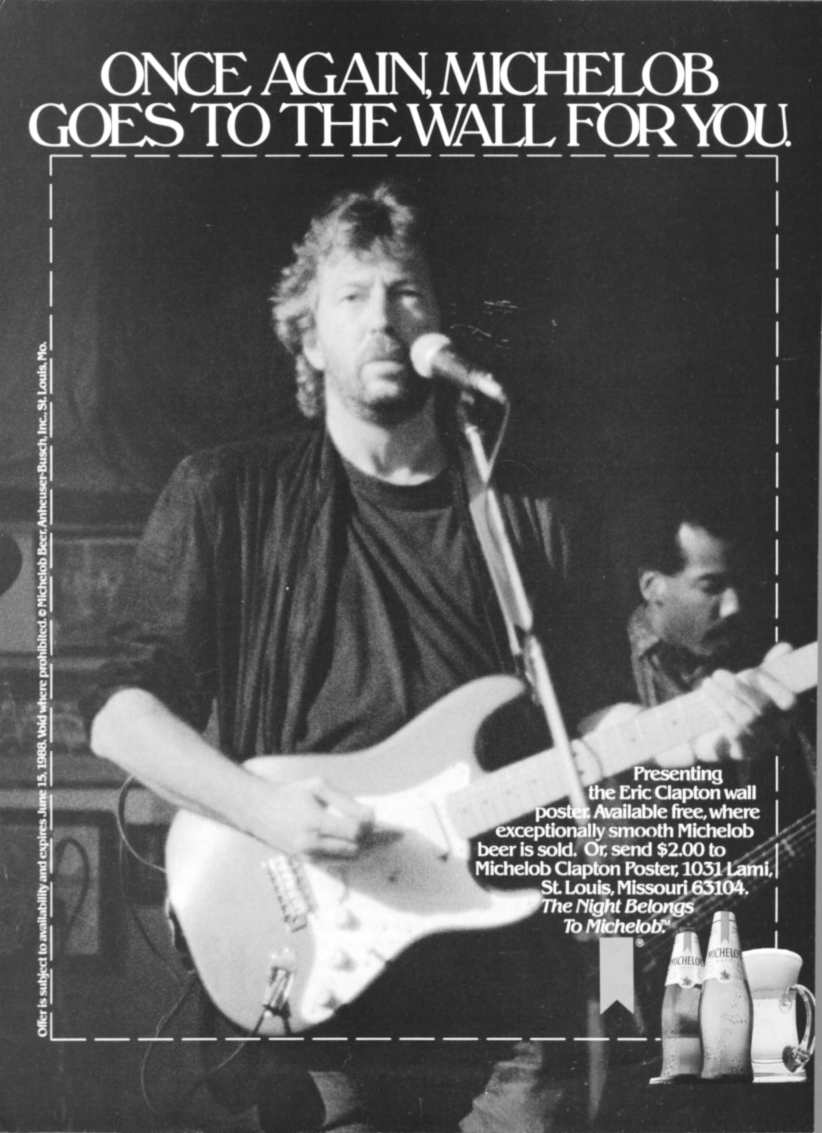

The brewers also have a lock on sports and on the music that appeals to young people. They sponsor rock concerts and have popular musicians play in their commercials. This can be ironic when the musicians get sober. Eric Clapton is a recovering alcoholic, who once said, “Alcoholism stunted my growth, both musically and in a human way. My ability to deal with close relationships is severely limited by the fact that I spent all my formative years completely anesthetized.” But far more young people will have seen Clapton in the Michelob commercials than will ever see that quotation.

Until quite recently, most of the heavy drinking done on college campuses and elsewhere was done by men. But young women are catching up—with tragic consequences. Adolescent females are significantly more at risk for becoming dependent on alcohol than are women in any other age group. This, of course, makes them important targets for alcohol advertisers. In the early 1960s about 7 percent of the new female users of alcohol were between the ages of ten and fourteen. By the early 1990s, the figure had increased to 31 percent.

Young women are drinking more heavily than ever before and are suffering terrible consequences. Females have less gastric alcohol dehydrogenase, an enzyme that digests alcohol in the stomach, than males do, so alcohol passes more quickly into the bloodstream. Thus females tend to get drunk faster, become addicted more quickly, and develop diseases related to alcohol abuse sooner than males. In addition to sharing the risks of addiction and early death with men, young women who drink heavily are more likely than their nondrinking counterparts to be the victims of rape and sexual assault and to have unwanted pregnancies. Those who become alcoholic are far more stigmatized than their male counterparts.

There is great debate about whether alcoholics share any personality traits. Most knowledgeable people think they don’t. However, some research indicates that the personality traits that influence high-risk drinking choices that can lead to alcoholism include gregariousness, impulsiveness, and rebelliousness. Certainly the advertisers, who spend billions of dollars on psychological research to identify their best customers and who understand alcoholics very well, appeal to these traits again and again in their advertising. Rebelliousness, more than any other trait, shows up in both the research and the ads. It is also, of course, a trait associated with adolescence—however, with very different parameters and consequences for females than for males.

Alcohol advertisers must walk a fine line. They want to appeal to our idealized images of ourselves, especially when we are young, as courageous rebels and free spirits, so they create ads such as the one for rum which features some half-dressed people on a tropical beach and the copy, “THERE’S A PART OF YOUR BRAIN that thinks clothes are overrated and loves to beat on drums and is not afraid of the IRS. . . . It relaxes with a cool Mount Gay on the rocks.” Beneath the name of the rum is the slogan “The Primitive Spirit Refined.”

The primitive spirit. Cuervo Gold uses the slogan “Untamed Spirit” and calls itself “the only shot guaranteed to release your inner lizard.” I guess your inner lizard is presumed to be friendly. And a new beer called Bad Frog, introduced in 1998, features on the label, and in its advertising campaign, a frog raising its middle finger, with accompanying slogans such as “He just don’t care” and “An amphibian with an attitude.”

But the advertisers have to avoid the dark side of rebelliousness, the aspects that are antisocial, even criminal, and that most of us know are dreadfully linked with alcohol. We must see ourselves as independent and successful individuals, never as isolated losers. This is especially true for men, who are far more likely than women to become involved in violent crime when drunk (women are more likely to be victimized). According to the Justice Department, alcohol is a factor in nearly 40 percent of violent crimes.

The crimes committed when alcohol is involved are often especially heinous. The young men who beat Matthew Shepard to death were homophobic, to be sure, but they were also extremely drunk, as were the racist thugs who dragged James Byrd to his death behind their pickup truck. Alcohol is by no means the cause of these atrocities, just as it is not the cause of rape and battering, but it is often gasoline on the fire of racism, sexism, and homophobia, as well as a convenient excuse for the perpetrators of such violence (in their own minds, as well as to the world).

In order to appeal to rebellious young people, especially young men, alcohol advertisers must link their product with defiance and assertiveness, but they must avoid reminding us of the link between alcohol and criminal violence. So they joke about aggression, as in a Southern Comfort ad featuring a tough guy sitting on a porch holding his pet alligator and the tagline “Next door they used to have a poodle.” According to the slogan, “Southerners have their own rules.” They create ads, such as one featuring a handsome scowling man on a motorcycle above the caption “A little uncivilized.” And they also put subtle pressure on the media not to make the links between alcohol and violent crime or to report that the majority of our nation’s prisoners are alcoholic or very heavy drinkers. A little uncivilized, indeed.

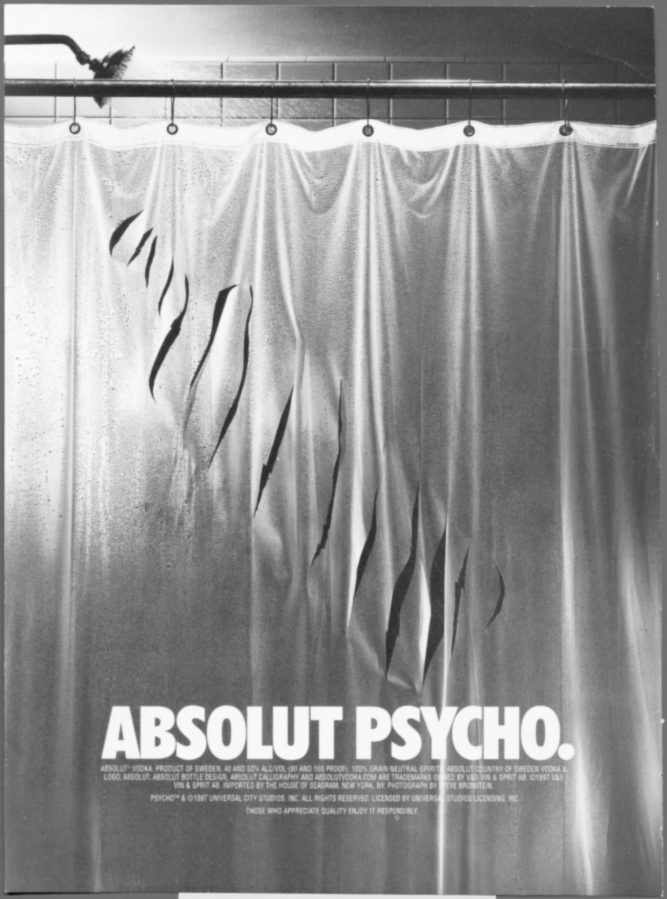

Sometimes violence is overtly portrayed in alcohol ads, as in the “Absolut Psycho” ad—but again in a way that is meant to be funny, just another ultra-hip cultural reference from Absolut, not a reminder that a woman was brutally stabbed to death in the shower in the film Psycho.

The only exception to this silence in advertising on the subject of alcohol and criminality that I’ve ever seen is a Coors Light commercial that features prisoners on a chain gang. An old man says, as images of mountains and a beautiful woman go by, “I’ve seen a place they call the Rockies, a place covered in snow as pure as the song of an angel. I’ve seen a place where the mountains rise up and call to you, ‘Run free and far.’” There is a pause and then one of the other prisoners says, “Tell us again, old man.” Given that alcohol and other drugs are involved in over half of all crimes, the chances are great that alcohol brought many of these prisoners to the chain gang, but they are still deluding themselves that it is a route to freedom.

A campaign for Molson Ice Beer walks the fine line between wildness and antisocial behavior. In one commercial, a wolf howls and a man’s voice says, “Tonight feels kind of weird, but it’s a good weird. I can feel it in my bones. This is not going to be your run-of-the-mill, laundry-doing, pizza-eating kind of night. I will not be exercising tonight or philosophizing or organizing. Tonight I’m going to look for women who look like trouble and I’m going to flirt with them heavily, because tonight I’m not just drinking beer—I’m gulping life. I’m going to eat the night alive. What are you going to do?”

In another commercial in the same campaign, the man says, “I’ve got a plan for tonight and the plan is to have no plan at all. Maybe I’ll send my left brain on vacation for a while and maybe I’ll let my soul be the boss. Maybe I’ll go to a party uninvited.” Of course, men who go out at night with no plans and crash parties often are not so welcome.

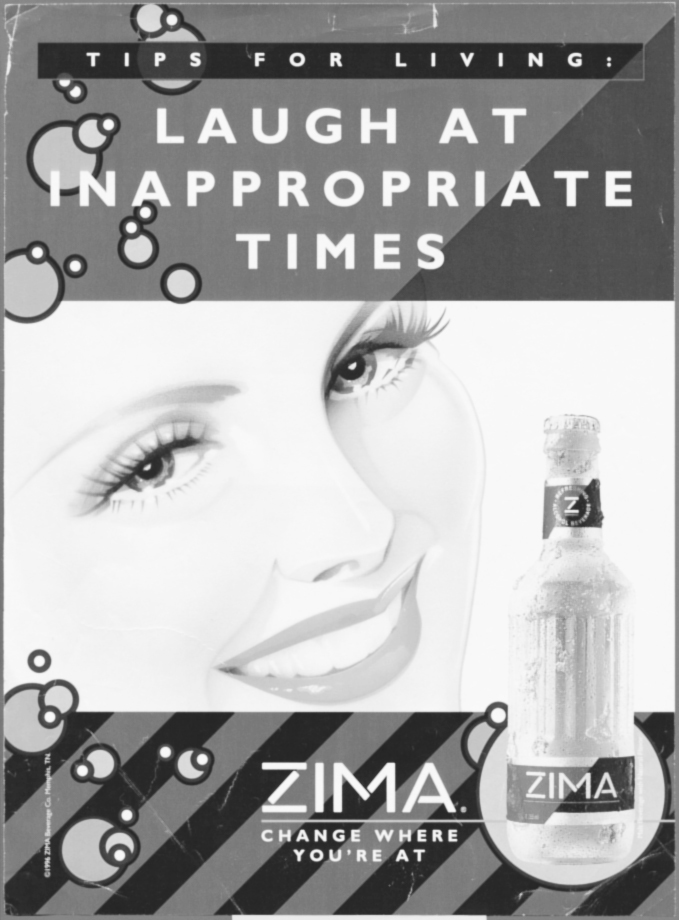

This promise that alcohol will liberate our wild selves is especially seductive for women. The definition of a “good girl” is so narrow, so repressive, so completely asexual and passive, no wonder so many would opt to be “bad” instead. But the social sanctions against “bad girls” remain terrifying. For all the talk about liberation and equality, overtly sexual women are still called tramps and sluts. This is especially true if they drink. So the wildness portrayed in the ads is attenuated. Men are going to “eat the night alive”—in a Zima ad, women are advised to “Laugh at inappropriate times.” Another ad in the same Zima campaign suggests that women “spend time with people you actually like.” This would be a daring act only for someone who was suffering from terminal niceness. “Forget the rules! Enjoy the wine,” says an ad featuring a young woman kicking up her heels. But it turns out the only rule she’s breaking is about the correct wine to drink with certain foods.

Throughout advertising and the popular culture we get the message that rebellious men are sexy and desirable, but rebellious women are not. Although it is fine for women to be feisty in a cute, spunky way, it is not at all fine for a woman to truly break the rules. She can pierce her tongue or her navel, but God forbid that she stops shaving her legs. She can smoke cigars or get a little high, but heaven help her if she becomes an alcoholic.

Indeed the first word most people think of when they hear the phrase “alcoholic woman” is “promiscuous.” The truth is that alcoholic women are not especially promiscuous. They are, however, very likely to have been the victims of sexual violence, both as children and adults. The alcoholic woman, acting in the very same way as the alcoholic man, is despised. I once heard a man, at a support group for alcoholics, talk about being very drunk and waking up in a motel with two women he didn’t know. The crowd laughed. Imagine the reaction if a woman told a story of waking up with two male strangers.

I often do an exercise in my workshops and seminars in which I call out the words “alcoholic woman” and ask people to respond spontaneously, to free-associate. I write the words on a blackboard. Always they are the same. Promiscuous, loose, tramp, slut, dirty, irresponsible, bad mother, pig, worthless. I ask the audience to choose the ones that apply only to women and they boil down to two descriptions: promiscuous and bad mother. As Marian Sandmaier says in her groundbreaking book The Invisible Alcoholics, these are the two worst things a woman can be accused of—to be indiscriminately sexual and to stop caring for men and children. The culture demonizes such women—alcoholics, prostitutes and now “welfare mothers.” They are the witches of our time, and their fate is a warning to the rest of us.

In ad after ad, film after film, alcohol (and cigarettes) are used as shorthand to convey to men that a woman is loose, wild, sexy. An ad for E-Z rolling papers features a sultry woman with a drink in one hand and a cigarette in the other. “The lady’s E-Z,” the headline says. “Two strikes against her,” says an ad for vitamins, which features a woman smoking and drinking.

However, these ads are for products other than alcohol and cigarettes. Alcohol advertisers have to be more careful. They want to attract men to the promise of seduction and sexual adventure and attract women to the promise of release from inhibitions and societal restraints without frightening women or portraying them as sluts. They often portray women as sexual and untamed but not too wild.

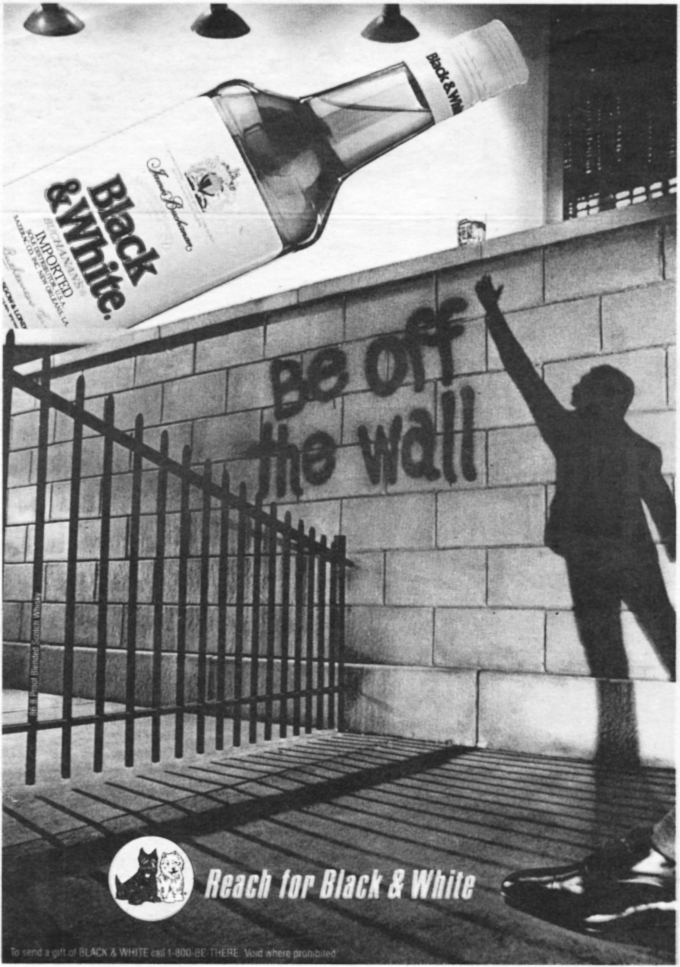

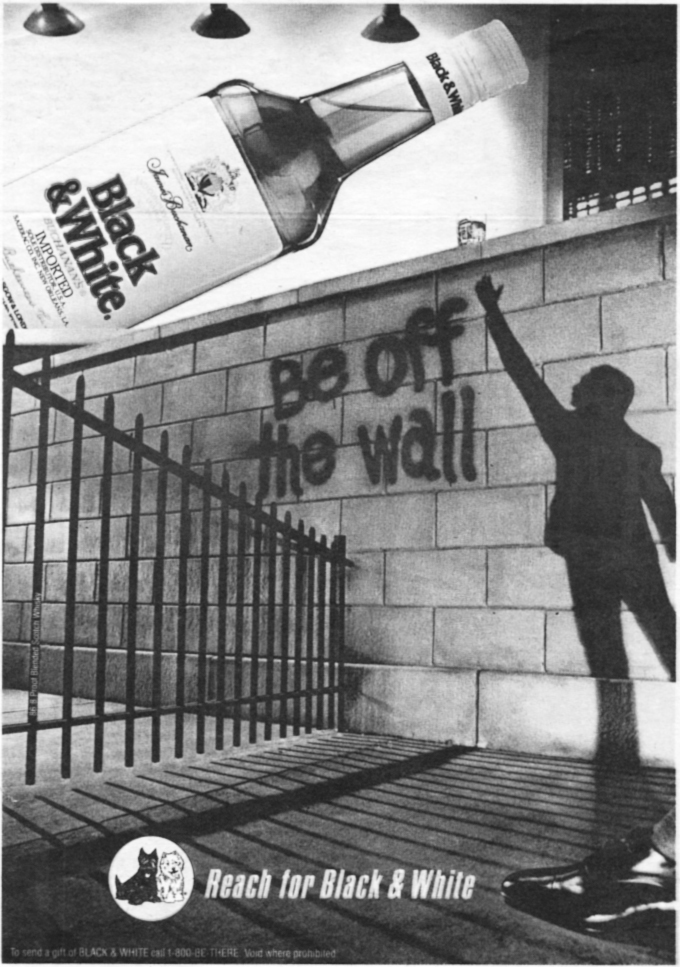

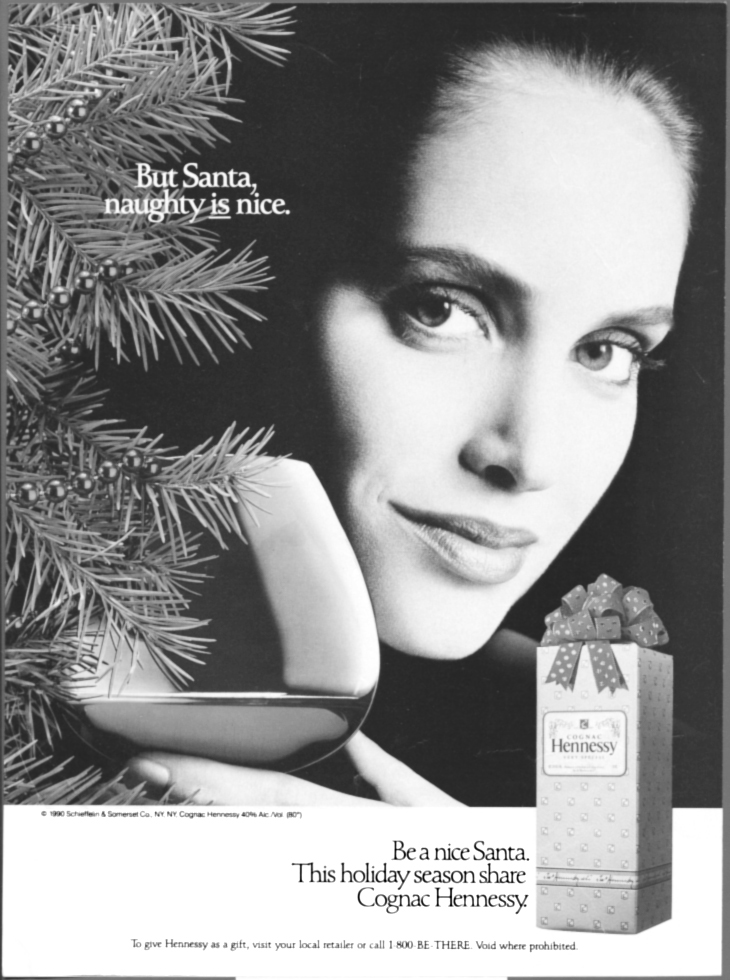

Slogans aimed at men, such as “The party animal” and “Be off the wall” are considered too raw and crude for women. Indeed it is hard to imagine an alcohol advertiser advising a woman to “be off the wall.” And I’d be stunned by a commercial that portrayed a woman going out into the night with no plans, perhaps crashing a party or flirting heavily with men who looked like trouble. If she did, the culture tells us she’d be asking for whatever happened to her. Rather, a woman looks out seductively, holding a glass of cognac, and says, “But Santa, naughty is nice.” This reminds me of the Mayflower Madam’s comment, when she was arrested for running a high-class prostitution service, “I wasn’t bad. I was naughty.”

An ad featuring a beautiful Nordic woman says, “If Inge Nielsen were a drink, she’d be Akvavit.” The copy continues, “Don’t let that innocent look deceive you. There’s passion close to the surface; a hint of spice and mystery; a breath-taking zest and liveliness.” Aha . . . she’s not bad, she’s lively. “If you never tried one, it would be a sin,” claims an ad for a drink called a “Black Angel.” It continues, “Being good has never been so easy. . . . But remember to take it easy; you wouldn’t want to lose your halo.”

A 1999 television commercial for Finlandia vodka directed by Spike Lee conveys a very similar message. The spot features a confessional scene. A hot-blooded temptress confesses her sins, one of which is drinking vodka. The priest remarks that even he sometimes drinks vodka. The woman asks which vodka. When he names Finlandia, the sinner reveals herself as an angel and says, “My Child, that is not a sin.”

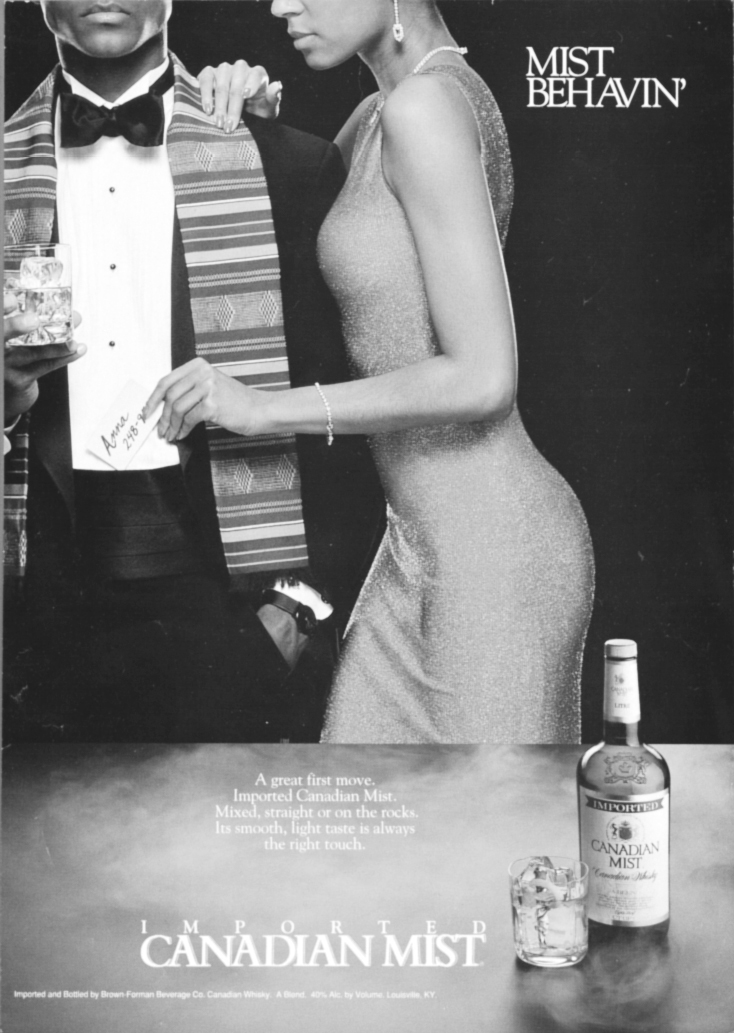

“A new way to gin” is the slogan for Tanqueray Malacca Gin in an ad featuring two sexy African-American women, described in the copy as “divine ladies.” And the woman in another ad who is slipping her phone number into a man’s pants isn’t a slut, she’s simply “Mist behavin’.” Drinking will liberate your wild, sexual self, these ads imply, but you’ll still be a good girl, even a “divine lady.”

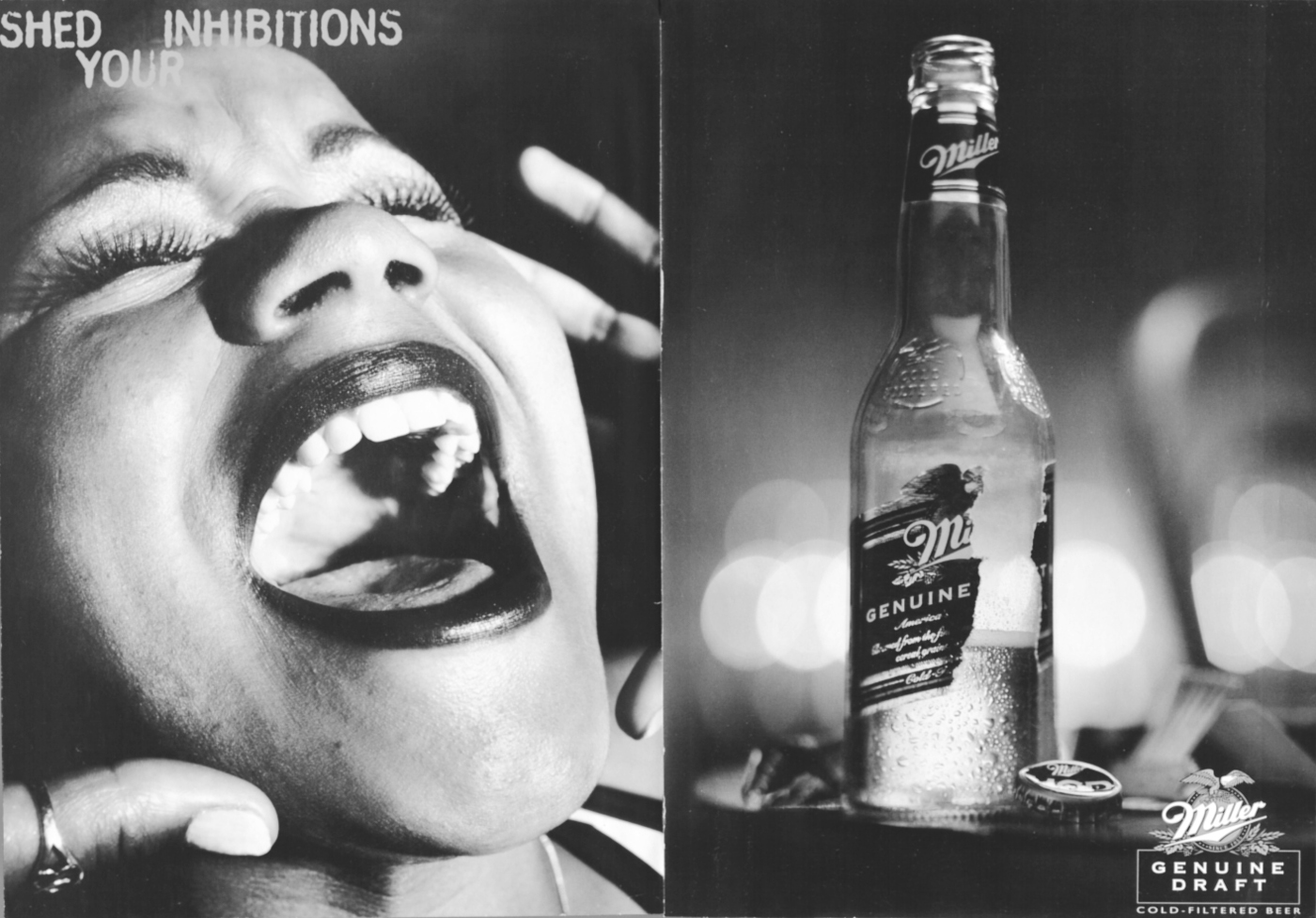

It’s no coincidence these women are African-American. “Shed your inhibitions,” shouts another African-American woman in a beer ad. I doubt advertisers would ever use a white woman in quite this way. As we all know, one stereotype of African-Americans is that they are more sexual than whites, so the image is more “acceptable.” In fact, it probably suggests to white women (and men) that the drink can give them the legendary sexual prowess of African-Americans.

When women in alcohol ads are portrayed as dangerous, it is because they are witches or sorceresses, not because they are really threatening. “Beware their magic spells,” says a Guinness poster in Malaysia, featuring a very voluptuous woman. “Make heavy objects fly across the room. Men,” says a liqueur ad that portrays a wild eye and the slogan “Princess of Darkness.” And a beautiful dark-haired woman stares out from a Pernod ad above the slogan “Dangerously Delicious.”

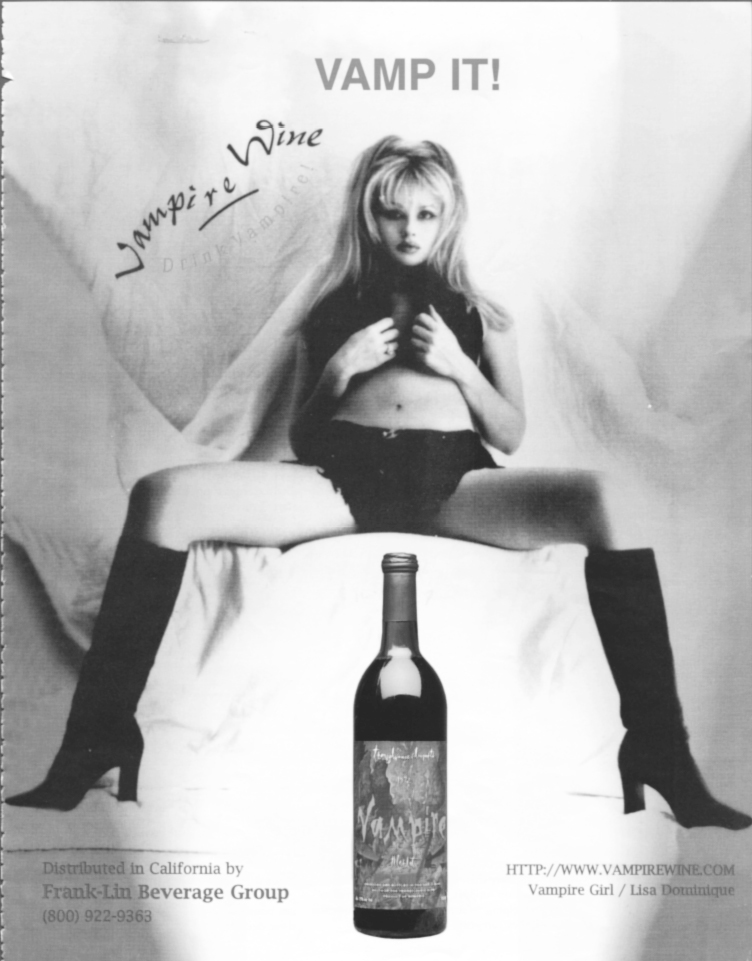

A Strega (Italian for “witch”) liqueur campaign features a beautiful woman with a black panther on her lap and the slogan “Spend some time with a Little Witch tonight.” Yet another ad features a woman as a vampire, but it is clear from her dress and her pose that it is not a man’s blood that she is likely to suck.

All of these ads, of course, target and appeal to grown women, and men too, but they are also inevitably irresistible to many girls, who long to have this kind of sexual power and sophistication and who are trying desperately to conform to the cultural mandate that they be both sensual and innocent, experienced and virginal (a trick requiring magic, if ever there was one). They know it is good to be considered a little wild and sexy, in a cute and impish way, but unspeakably terrible to really cross the line. They see all the time what happens to the girls who are labeled sluts, the girls who are raped, the girls whom even other girls viciously turn on.

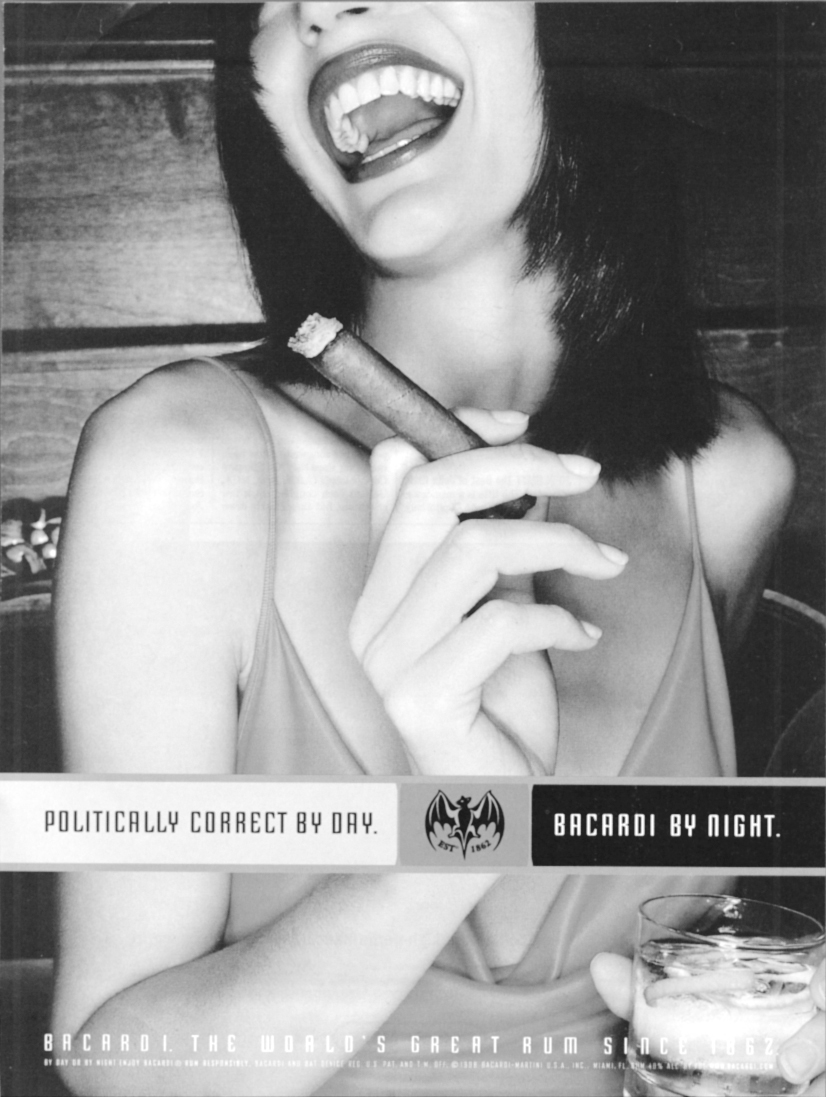

A Bacardi rum campaign promises them that they can have it all: They can be “Banker by day. Bacardi by night” as one ad says, featuring the torso of a young woman with a pierced navel. Another ad in the campaign features a young woman smoking a cigar and laughing uproariously, with the tagline “Politically correct by day. Bacardi by night.” This ad accomplishes many things for Bacardi. It trivializes the terrible health consequences of smoking and drinking for women by describing the opposition as mere political correctness. It promises young women that alcohol will liberate them, especially sexually (the woman is wearing a very low-cut red dress, after all). And it encourages and normalizes personality change via drinking, one of the symptoms of alcoholism.

The alcohol industry, like the tobacco industry, has been targeting women with the theme of liberation for many years. An ad in the mid-1970s featured a beautiful but tough-looking woman seemingly alone in a bar or restaurant and the copy, “Isn’t it time you knew an exciting drink to order?—instead of taking a man’s suggestion.” Around the same time, Chivas Regal ran an ad with a woman’s beautifully manicured hand reaching for the bottle on the shelf and the copy, “Now that you’re bringing home the bacon, don’t forget the Chivas.” More recently, Miller ran a series of ads featuring women rodeo riders and the headline “American Rodeo Riders and Their Beer.” And a campaign for rum featured women in nontraditional athletic gear and the slogan “Break tradition.”

More often these days, the woman is liberated but adorable, girlish, not tough like many of the women in cigarette ads. A 1997 Miller beer commercial features a closeup of a dartboard and, one after another, three darts hitting the center to increasing gasps from the unseen audience. Then there’s a giggle and a female voice says, “I swear I’ve never played this before.” It is understood that she is in the bar, she’s drinking beer, she’s even winning at darts. She can do anything a man can do . . . but she’s cute, unthreatening. “Rivals by day, Bacardi by night,” says yet another ad in the Bacardi campaign. In this one, a woman wearing a very low-cut red dress, her breasts exposed, is pulling on a laughing man’s tie. Again, she may be trying to compete with him by day—but at night she’s just another sex object.

Heavy drinking is seen by the culture as something that makes both men and women more masculine. Therefore, it is considered somewhat desirable for men but repellent for women. A man who drinks heavily is often lionized, considered more virile. He is seen as someone “larger than life,” with hearty appetites, robust and vigorous. This creates a further challenge for advertisers who wish to target women. They can and do offer alcohol to men as a way to be more manly (“Not every man can handle Metaxa,” says one ad), but they can’t suggest that drinking heavily will make women more feminine.

However, they can imply that drinking will give a woman some of men’s power and privilege without detracting from her femininity. Thus they often use male symbols, such as cigars, in alcohol ads but only in the hands of stereotypically feminine and beautiful women. A recent campaign for Jim Beam bourbon advises women (and occasionally men) to “Get in touch with your masculine side.” In one of these ads a woman smokes a cigar, in another she flicks a lighter, and in a third she stands by a refrigerator and drinks milk from the carton. The ads work only because all of the women are conventionally beautiful, usually wearing lots of lipstick and dark nail polish. Imagine if they were butch instead of femme.

In a Cazadores tequila ad, in addition to the cigar, the woman seems to be wearing a man’s shirt . . . but it is way too big for her and is sexily slipping off her shoulders. She’s playing with symbols of power, but they don’t really fit her. Not to worry!

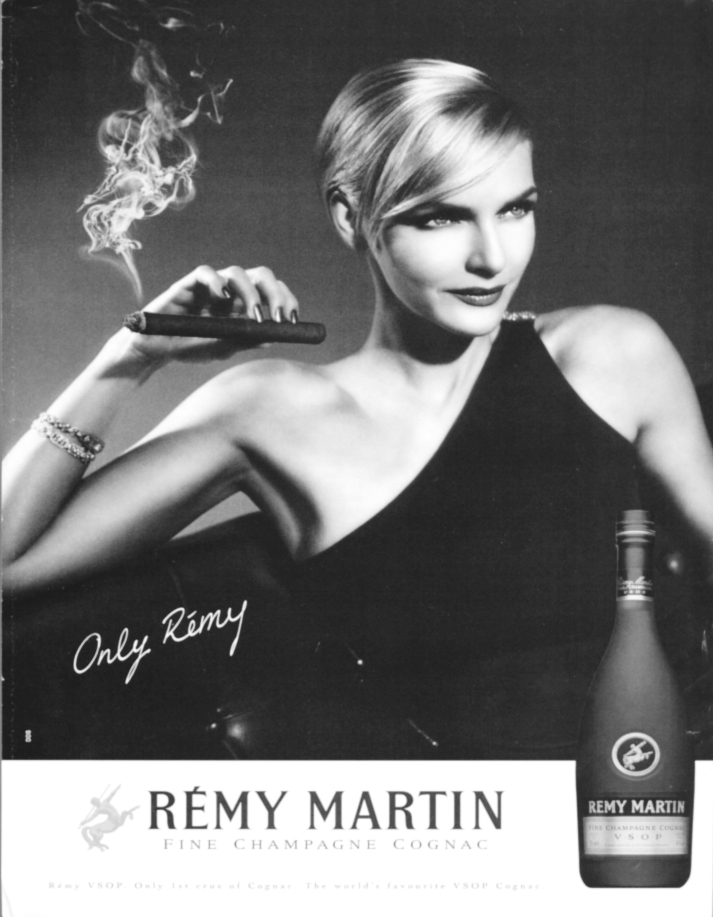

In a Remy Martin cognac ad, the woman seems to be releasing fiery sexual passion via her cigar. The figure in the fire looks like a centaur, holding a spear. The woman’s short hair and broad shoulders contribute to an impression of strength and masculinity, but her heavy makeup and slinky dress contradict this. This ad evokes a more complicated reaction than the others, however, partly because this person could in fact be a man.

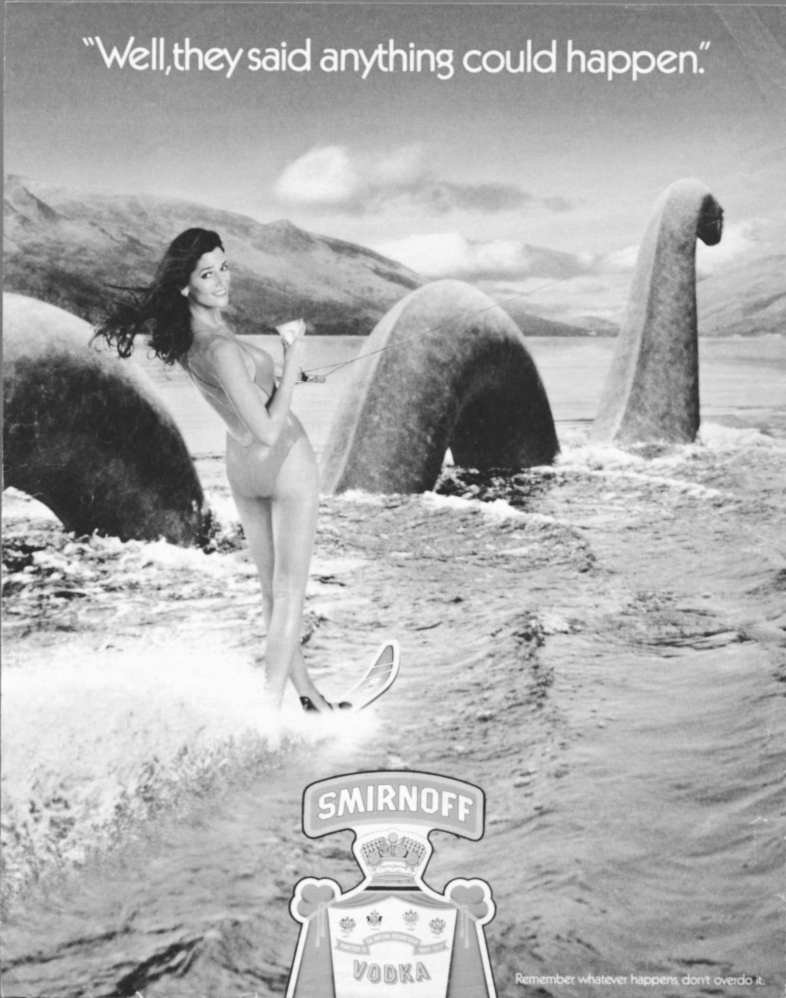

Alcohol advertisers sometimes use transsexuals in their ads—or men made up to look like women. The waterskier in a Smirnoff ad is a well-known British transsexual. Perhaps advertisers do this not only because these people are beautiful, but because it adds to the sense of androgyny, the promise of liberation and power, and the spice of rebellion. And because it is trendy these days, in certain circles, to be cool about bisexuality, transvestism, and transsexualism. Indeed the famous transvestite RuPaul is a popular model.

Consider a cartoon-style vodka ad showing a confident-looking woman holding a drink and saying, “Three things you should know, Love. The name’s Mel. The drink’s Tanqueray Sterling Vodka. And how unreasonable I can be if you forget the first two.” It’s no coincidence that she has short hair and a name that could be male or female.

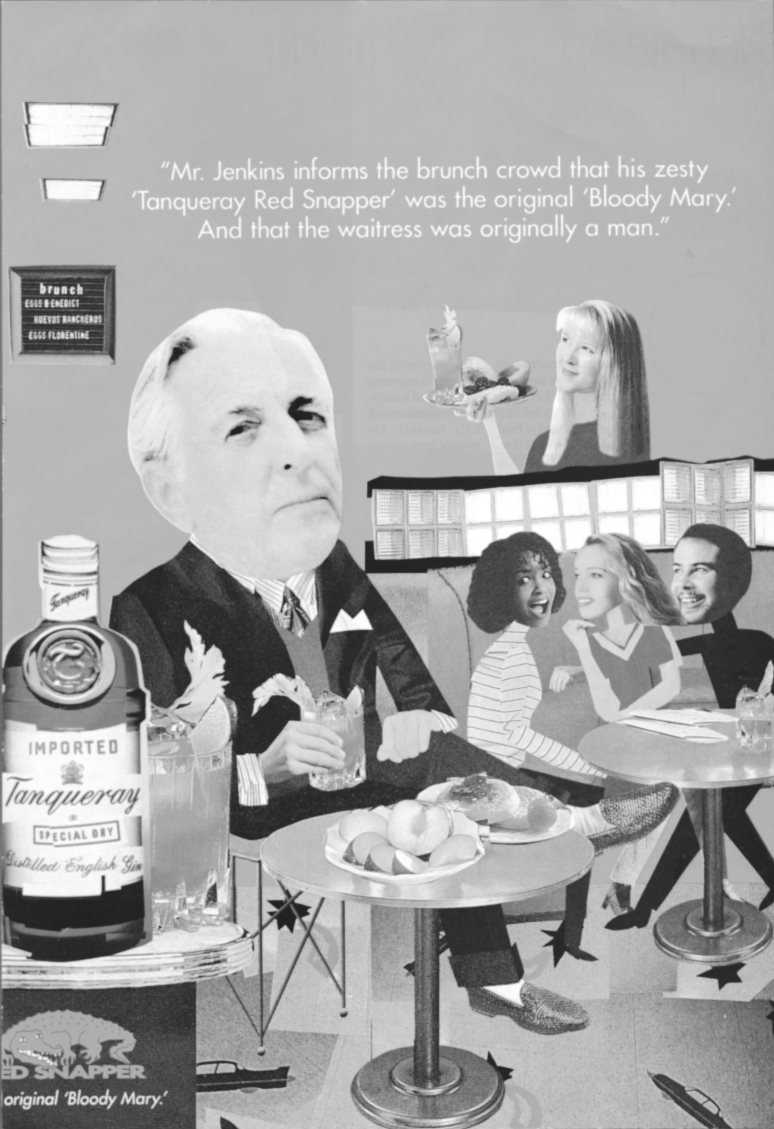

A twist on the gender-bender theme is found in a three-page ad for Seagram’s that ran in the 1997 swimsuit issue of Sports Illustrated. On the back cover is a pair of stereotypically shapely (and shaved) legs. But the fold-from-the-spine page opens to reveal the limbs are attached to a male beach bum. The tagline: “You either have it or you don’t.” And a gin ad featuring the ubiquitous Mr. Jenkins says, “Mr. Jenkins informs the brunch crowd that his zesty ‘Tanqueray Red Snapper’ was the original ‘Bloody Mary.’ And that the waitress was originally a man.” We can have it all indeed.

Several researchers have identified shame at having failed at the gender expectations of being female as an important issue for female alcoholics. One response to this shame is to mythologize it. I’m not only a bad girl—I am the baddest. I’m a rebel, an outlaw. I’m deeper, more complex, more interesting than ordinary women. The rules don’t apply to me.

Looking back on my own life, I can see now that I thought I was a really bad girl, a bad seed. There was a terrible gap, an abyss, between my image and my essence, and smoking and drinking helped me feel more integrated. The self who smoked and drank always seemed more real to me, more true, than the one who turned in careful homework assignments and kept a tidy house. There were complex contradictions about this in my psyche. On the one hand, I felt bad because I believed, as most children do, that I was somehow responsible for my mother‚s death (if I had been a better girl, she wouldn’t have abandoned me). On the other hand, I think I knew somehow that the roles for women were terribly restrictive and that I would have to sacrifice my sexuality and my authenticity in order to be “feminine.” So I was both terribly wrong and terribly right.

In truth, alcoholic women are more likely than nonalcoholic women to chafe against rigid sex roles, to be androgynous. Many theorists believe that gender socialization is another primary factor (along with early trauma) in the development of alcoholism and other addictions among women. The women most vulnerable to addiction are those who feel most keenly the conflict between their true selves and the societal definition of the “good girl.” This conflict is intensely painful and addictions help numb the pain. According to researcher F. B. Parker, “Alcoholism represents the ransom a woman pays for her emancipation.”

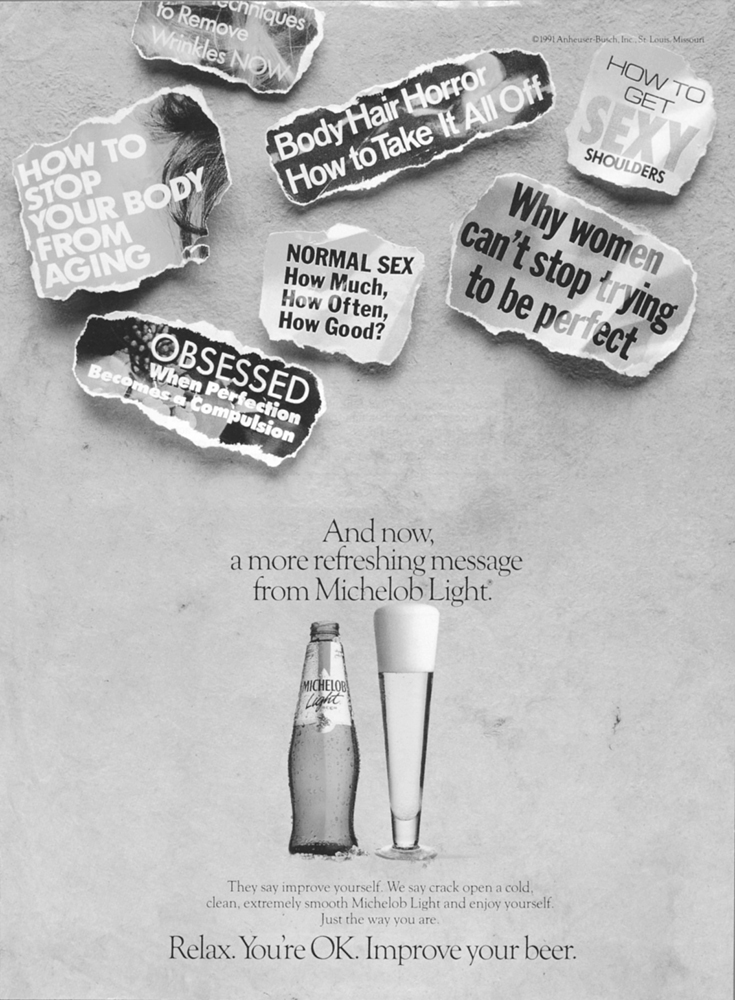

This is hinted at in a 1991 ad that ran in almost all the major women’s magazines. Juxtaposed with the titles of articles typical of these magazines, such as “Body Hair Horror,” “How to Stop Your Body from Aging,” “Blast Jiggly Hips and Thighs,” and “Fixing Every Flaw,” was a bottle of Michelob and the headline, “And now, a more refreshing message from Michelob Light.” The copy continues, “They say improve yourself. We say crack open a cold, clean, extremely smooth Michelob Light and enjoy yourself. Just the way you are. Relax. You’re OK. Improve your beer.”

I suppose on the surface this could seem like progress—telling women to ignore all these terrible exhortations. But on a deeper level the ad is simply reminding us of them—and then offering the beer as a way to cope, maybe even as a way to think of oneself as rebelling against these edicts. Another more recent and much more subtle ad pictures a woman with a list of descriptive nouns superimposed on her face, many of them contradictory (“optimist” and “pessimist,” for example). “Appropriately complex” is the tagline, which is meant to refer to the woman and to the cognac being advertised. Perhaps the drink will help her resolve some of these contradictions, will enable her to pull herself together, so to speak.

Addiction is in some sense a logical response to powerlessness and rigid gender stereotypes. These stereotypes harm everyone—the girls who are denied access to their powerful selves and the boys who are denied access to their emotional selves—and, on some level, we all know it. Some people resist more than others. Some succeed, others go under.

It is not surprising that many girls and young women turn to alcohol and that alcohol advertisers target them. In the beginning, alcohol can seem to help a girl deal with the cultural contradictions, to give her some kind of connection she can count on, even if it is only the illusion of connection, to numb the pain of losing her real self, and to serve as an acceptable substitute for true rebellion.

There is also another product that is presented in advertising as absolutely perfect for a girl who wants to rebel without taking any real risks (except to her own health), who wants to escape from the trap of being a “good girl” without taking the punishment meted out to “bad girls,” who wants to seem liberated without being stigmatized as a feminist, who wants to stay thin, and who, throughout all of it, needs a way to repress her rage at what is being done to her. That product is a cigarette.