“WHAT YOU’RE LOOKING FOR”

Rage and Rebellion in Cigarette Advertising

![]()

OF ALL THE LIES THAT ADVERTISING TELLS US, THE ONES TOLD IN CIGARETTE ads are the most lethal. Sometimes the pernicious effects of advertising are unintended, but this is certainly not the case with cigarette advertising. The tobacco industry is in the business of getting children addicted to nicotine. It has to get three thousand children to start smoking every day simply to replace those smokers who die or quit (in the United States alone). Why children? Because 90 percent of all smokers start smoking before they are eighteen years old and 60 percent start before high school. Almost all smokers start in their teens (or earlier) and the age of initiation has been dropping steadily, especially among girls. Today about one-third of high-school-aged adolescents in the United States smoke or use spit tobacco, and the numbers are rising, especially for African-American teens.

If you don’t start smoking when you are very young, the chances are you will never start. Very few people wake up one morning at the age of twenty-two or twenty-seven and say to themselves, “I have a good idea. I think I’ll take up the deadliest, most addictive product of all.” And no one in midlife says, “I think I’ll try something to make me look older.” Children smoke because they want to feel more grown-up, more powerful. Teenagers smoke mostly because they want to rebel, to feel cool. They start for these reasons and then most of them become addicted, because nicotine is the most addictive drug of all. The tobacco industry wants us to think of smoking as an “adult custom.” The truth is that it is an addiction that begins in childhood, a “pediatric disease.”

What are the consequences for these three thousand children who become regular smokers every day? Seventy percent will regret their decision to smoke and will try to quit while still in their teens. Very few will succeed. Joseph Califano, Jr., former secretary of health, education and welfare, said, “Virtually all will be sicker than the rest of the population, most will never quit, and more than a third face early death as a consequence of their addiction.” Tobacco advertisers deliberately seduce children with a promise of power, sex appeal, sophistication, and rebellion, but what they are really selling them is shortness of breath, yellow teeth, wrinkles and, quite possibly, emphysema, heart disease, and lung cancer. A 1999 study found that smoking in the teenage years causes permanent genetic changes in the lungs and forever increases the risk of lung cancer, even if the smoker quits.

Almost nothing good can truthfully be said about cigarettes. Highly addictive, the damage they do to health has been documented by over sixty thousand research studies. Cigarettes kill more Americans each year than alcohol, cocaine, heroin, fires, car crashes, homicide, suicide, and AIDS combined. Indeed, smoking is the single largest preventable cause of death in America (and, according to former surgeon general C. Everett Koop, the most important public health issue of our time). Yet we sell cigarettes in pharmacies, we sell them in candy stores to children. Over one thousand people die every day due to cigarette-related diseases, in the United States alone. In the twentieth century, tobacco has killed more people than war. Based on current trends, by the year 2030, the worldwide death toll will rise to ten million per year, with 70 percent occurring in developing countries.

Unlike other potentially dangerous products such as alcohol, there is no such thing as moderate, low-risk use of tobacco. Indeed tobacco is the only product advertised that is lethal when used as intended. There is abundant evidence that cigarette smoke is also harmful to nonsmokers, especially to children. Smoking is also heavily implicated in lost productivity and fire deaths and damage. The World Bank has estimated that the use of tobacco results in a global net loss of $200 billion each year. These costs include direct medical care costs for tobacco-related illnesses, absenteeism from work, fire losses, reduced productivity, and forgone income due to early mortality.

In spite of these appalling statistics, smoking has been promoted for decades by the most massive marketing campaign ever dedicated to a single product. While spending over five billion dollars a year in the United States alone on advertising and promotion, the tobacco industry ironically denies that this advertising has any effect. It insists that it does not target nonsmokers or young people and that the whole point of all that advertising is simply to get smokers to switch brands. Only 10 percent of the nation’s fifty-five million smokers switch brands every year. It is obvious that the tobacco industry needs to aggressively recruit new smokers to replace those who die or quit. When you’re selling a product that kills people, you’ve got a problem. Your best customers die.

Nowhere is the distorted perspective of advertising, a perspective that manages to screen out almost all unpleasant reality except the strictly personal (such as bad breath, facial hair, and fat), more obvious than in the cigarette ads. The contradictions abound. Macho men apparently owe their freedom and independence, indeed their very masculinity, to their Marlboros, although the evidence is clear that cigarettes are linked with impotence, lower testosterone count, and sterility.

In fact, Marlboros began as a cigarette designed for women. It came with a red tip so the smoker’s lipstick wouldn’t show, and the slogan was “Cherry tips to match your ruby lips.” It didn’t take long for Philip Morris, makers of Marlboro, to realize that this wasn’t a good idea. A woman will most often freely use a product designed for men, but God forbid that a man would ever use a product designed for women. How many men smoke Virginia Slims? The group with higher status rarely wants to use a product designed for a lower-status group. So in 1956 Marlboro was repositioned as the ultimate man’s cigarette, with the image of the cowboy. This campaign has been phenomenally successful. Almost one-third of American smokers smoke Marlboros, the most heavily advertised cigarette in the world, and the Marlboro Man was recently named by Advertising Age as the top advertising icon of the century. At least one writer for the magazine mentioned the irony of a “supposed symbol of rugged independence” really being a “symbol of enslavement to an addictive drug.”

People start smoking and become addicted for many reasons, of course, and no one suggests that tobacco advertising is the primary one. However, cigarette advertising aggressively targets those very people most vulnerable to nicotine addiction. And it promotes a climate of denial. It is difficult for children to take health warnings seriously when they are surrounded by billboards of cartoon characters smoking, when the hottest (and coolest) celebrities light up in films and television programs and concerts, when the magazines in their homes are filled with colourful ads for cigarettes. A 1999 study found that more than two-thirds of the fifty G-rated animated films released by major studios during the past sixty years portray alcohol or tobacco use without any clear messages of negative health effects. Current research suggests that tobacco advertising has two major effects: It creates the perception that more people smoke than actually do and it makes smoking look cool. It seems that the rest of the media help further these perceptions.

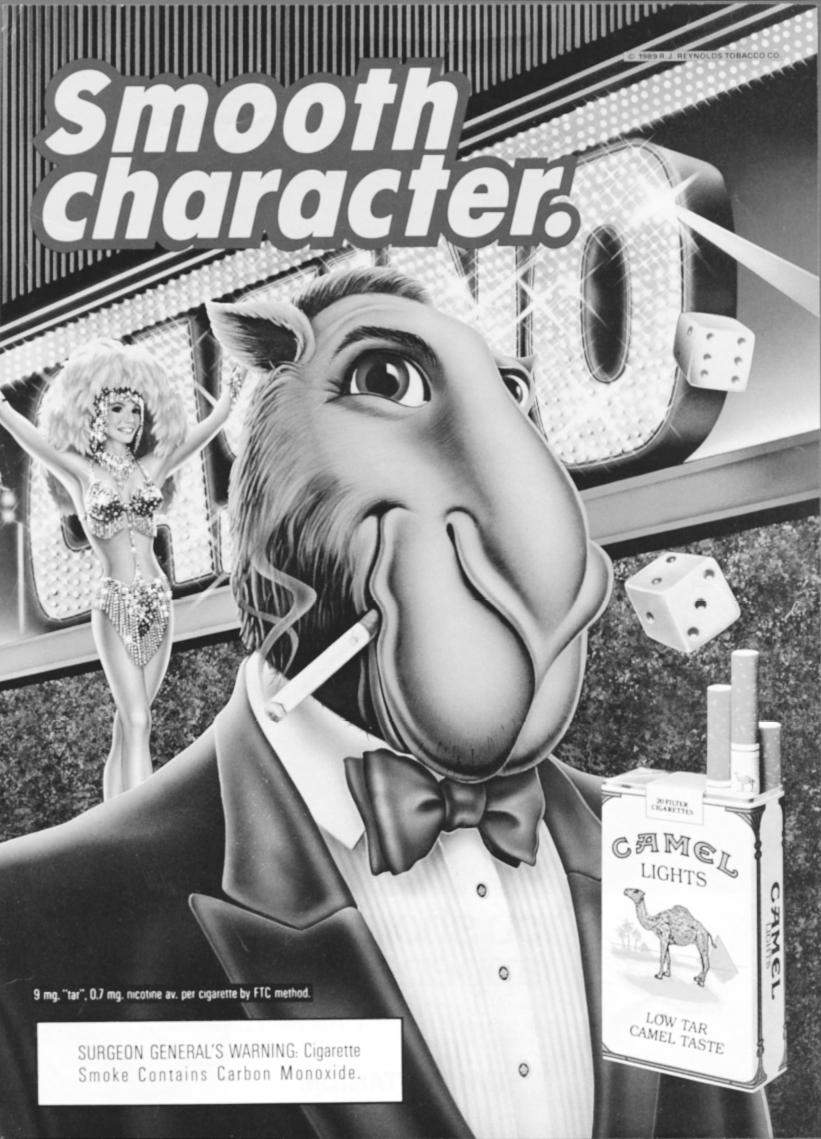

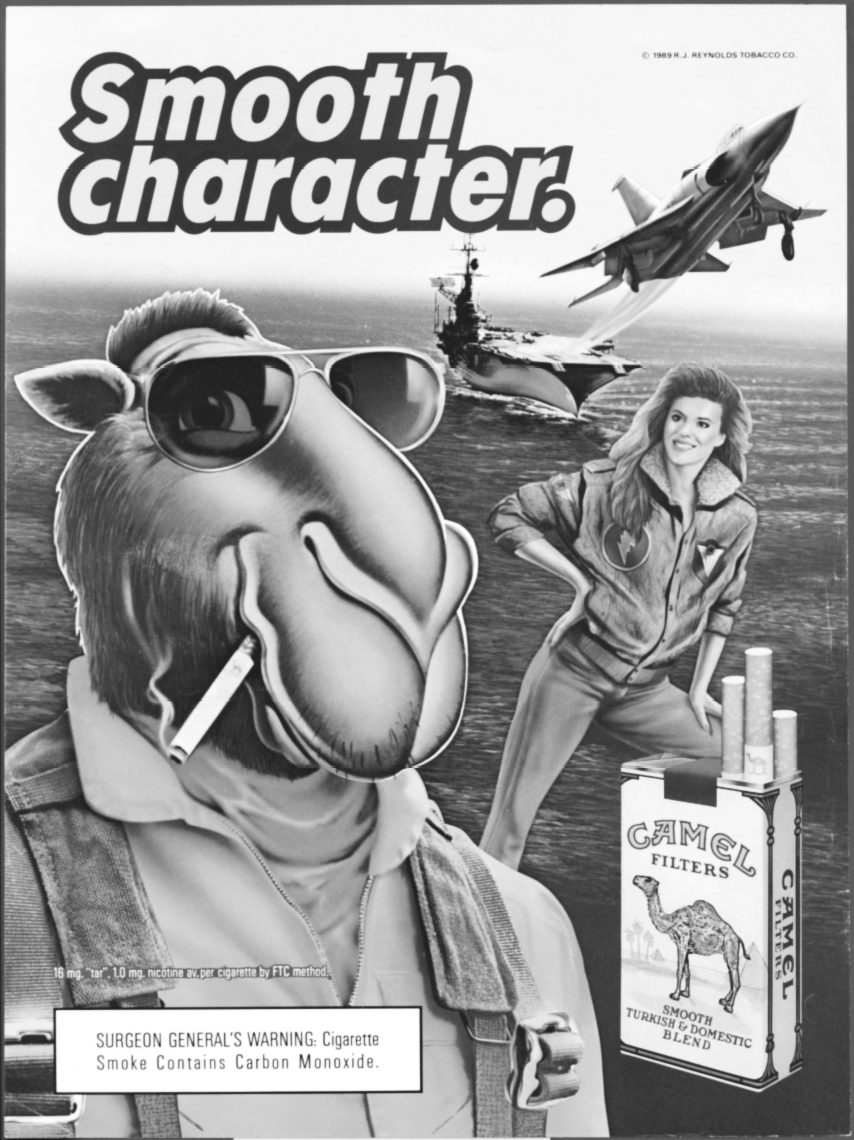

One of the most successful campaigns in the history of advertising was the one for Camel cigarettes that ran from 1988 until 1997. Just about everyone remembers this campaign, which featured a cartoon camel doing lots of “cool” things, like playing in a rock band, shooting pool, and riding a motorcycle. This camel, known as Old Joe, is now as recognizable to six-year-olds as is Mickey Mouse. One-third of all three-year-olds can link him with cigarettes.

Before the advent of this campaign, Camels did not especially appeal to young people. Of smokers under the age of eighteen, less than 1 percent smoked Camels. Soon after the introduction of Joe Camel, the percentage of teen smokers who smoked Camels sky-rocketed to 33 percent. This certainly says something about the power of advertising. The fact that the campaign was finally abolished after years of citizen activism against it says something also about the power of protest. Alas, the campaign was abolished only in the United States. Old Joe continues to entice children in other countries around the world.

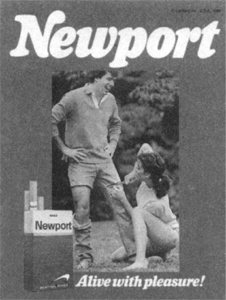

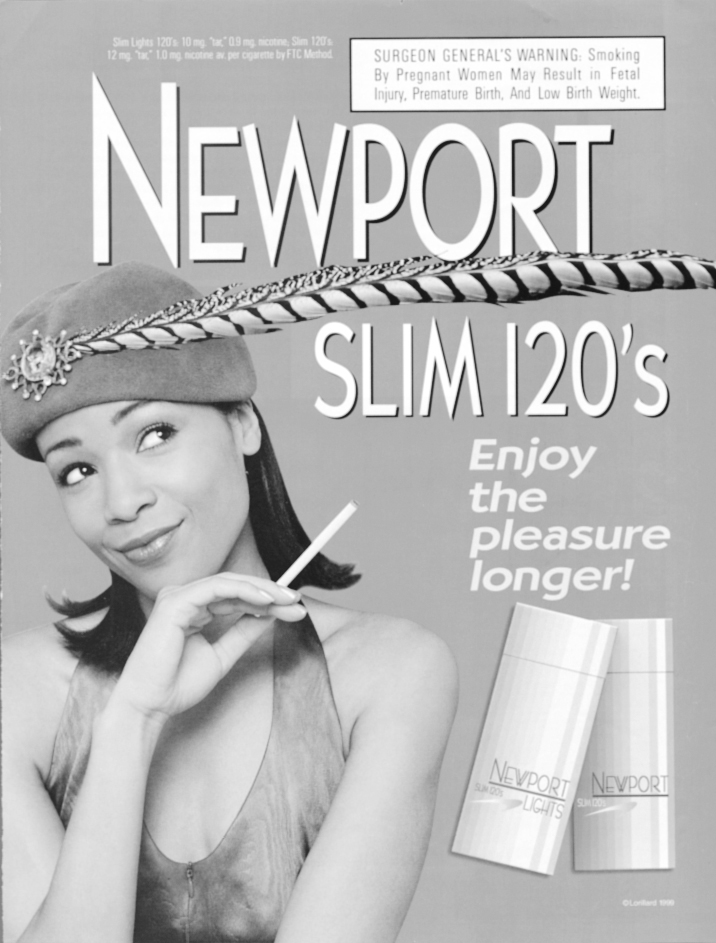

Eighty-six percent of all teenage smokers smoke one of the three most heavily advertised brands—Camels, Marlboros, or Newports. As further evidence of the influence of advertising, 70 percent of young African-American smokers smoke Newports, the third-most-advertised brand overall and the number-one brand advertised to African-Americans. Almost all of these teenagers would vehemently deny that advertising had any influence on their “choice,” but the statistics speak for themselves.

Recent research also supports this. Several studies have demonstrated an association between exposure to cigarette advertising and adolescent smoking behavior, while others have shown that young people smoke the most heavily advertised brands. According to one of these studies, tobacco advertising and promotion influence teenagers’ decision to begin smoking significantly more than does peer pressure. The same team of researchers found that sudden rises in adolescent smoking coincided with large-scale cigarette promotional campaigns. According to John Pierce, the lead author of the studies, “It is not that children see an ad and immediately start to smoke, but seeing the ads and handling the cigarette packs and the promotional gifts lessens their resistance, weakens their resolve, so that later on they will be somewhat more willing to accept a cigarette from a peer when it is offered.” Pierce conducted a longitudinal study that conclusively demonstrated that over a third of all youthful experimentation with cigarettes is directly attributable to cigarette advertising and promotions.

The tobacco industry claims these studies are rigged, of course, and that advertising has no effect on young people. Even advertisers scoff at this preposterous claim. In one poll, 71 percent of advertising executives said they think cigarette advertising increases youth smoking and nearly 80 percent approved of advertising restrictions to reduce its effect on kids and teenagers. According to Rance Crain in an editorial in Advertising Age, “Cigarette people maintain peer pressure is the culprit in getting kids to start smoking and that advertising has little effect. That’s like saying cosmetic ads have no effect on girls too young to put on lipstick.”

The late Emerson Foote, founder of Foote, Cone & Belding and former chairman of the board of McCann-Erickson, one of the world’s largest advertising agencies, said of the industry’s claims that its advertising only affects brand-switching, “I don’t think anyone really believes this. . . . I suspect that creating a positive climate of social acceptability for smoking, which encourages new smokers to join the market, is of greater importance to the industry. . . . In recent years, the cigarette industry has been artfully maintaining that cigarette advertising has nothing to do with total sales. Take my word for it, this is complete and utter nonsense.” Bob Garfield of Advertising Age goes further: “Watch any child when a cartoon image comes on TV; it’s a moth to flame. And R.J. Reynolds knows it, and has always known it, and when they start mouthing their line about smoking as an ‘adult decision,’ may they choke on their lying tongues.”

The tobacco industry has spent a fortune on research designed to understand the psychology involved in getting young people to smoke. This research has found that people in their early and mid-teens are beginning to shape their self-image, to differentiate themselves from their parents and other adults, and that cigarette advertising can exploit this natural need by offering a destructive manner of rebellion as an alternative to more constructive varieties, such as outrageous music, fashion, and politics. It is important to get children while they are young “so that the habit may become an integral part of the image of themselves. . . . The temptation must be pressed just as the sense of self is forming, just as the child is facing the world at large for the first time, or it will not take hold.”

The evidence against cigarette advertising is compelling enough that about thirty countries, including those of the European Union, have banned all tobacco advertising and sponsorships. A survey conducted by the American Cancer Society found that countries that severely restricted tobacco promotion experienced the greatest annual declines in tobacco consumption.

After years of banding together, there finally has been a break in the stone wall of the tobacco industry. In 1997 the Liggett Group, the smallest of the five major tobacco companies, defected from the rest of the industry by admitting that nicotine is addictive, that smoking causes cancer, and that the industry targets young people. Tobacco industry documents, brought to light by whistle-blowers and by product liability suits against the industry, certainly support these allegations. Knowing that teenagers are particularly susceptible to peer pressure, the industry creates the illusion of peer acceptance in its ads. As one R.J. Reynolds document says, “Overall, Camel advertising will be directed toward using peer acceptance/influence to provide the motivation for target smokers to select Camel.” The document continues that Camel advertising will create “the perception that Camel smokers are non-conformist, self-confident and project a cool attitude, which is admired by their peers. . . . Aspiration to be perceived as a cool member of the in-group is one of the strongest influences affecting the behavior of younger adult smokers.”

One series documents Brown & Williamson Company’s efforts to attract youth smokers with sweet-flavored cigarettes, including some with a cola-like taste. The company also considered tobacco-based lollipops, cotton candy, and fruit roll-ups. “It’s a well-known fact that teenagers like sweet products. Honey might be considered,” says one memo (which is titled “Project Kestrel,” after a small bird of prey). And one of the most chilling documents records a study in which Philip Morris researchers tracked “hyperkinetic” grade-schoolers to determine if such children would become cigarette smokers. According to the report, “We wonder whether such children may not eventually become cigarette smokers in their teenage years as they discover the advantage of self-stimulation via nicotine. We have already collaborated with a local school system in identifying some such children in third grade.”

Of course, the industry targets children. How could they not? As an R. J. Reynolds memo says, “the 14 to 24 age group . . . represents tomorrow’s cigarette business.” “The base of our business is the high-school student,” says a memo from a Lorillard executive. And a Philip Morris report says, “Today’s teenager is tomorrow’s potential regular customer.” This can seem innocuous enough until one remembers that almost half of the tobacco industry’s “regular customers” die prematurely from cigarette-related diseases.

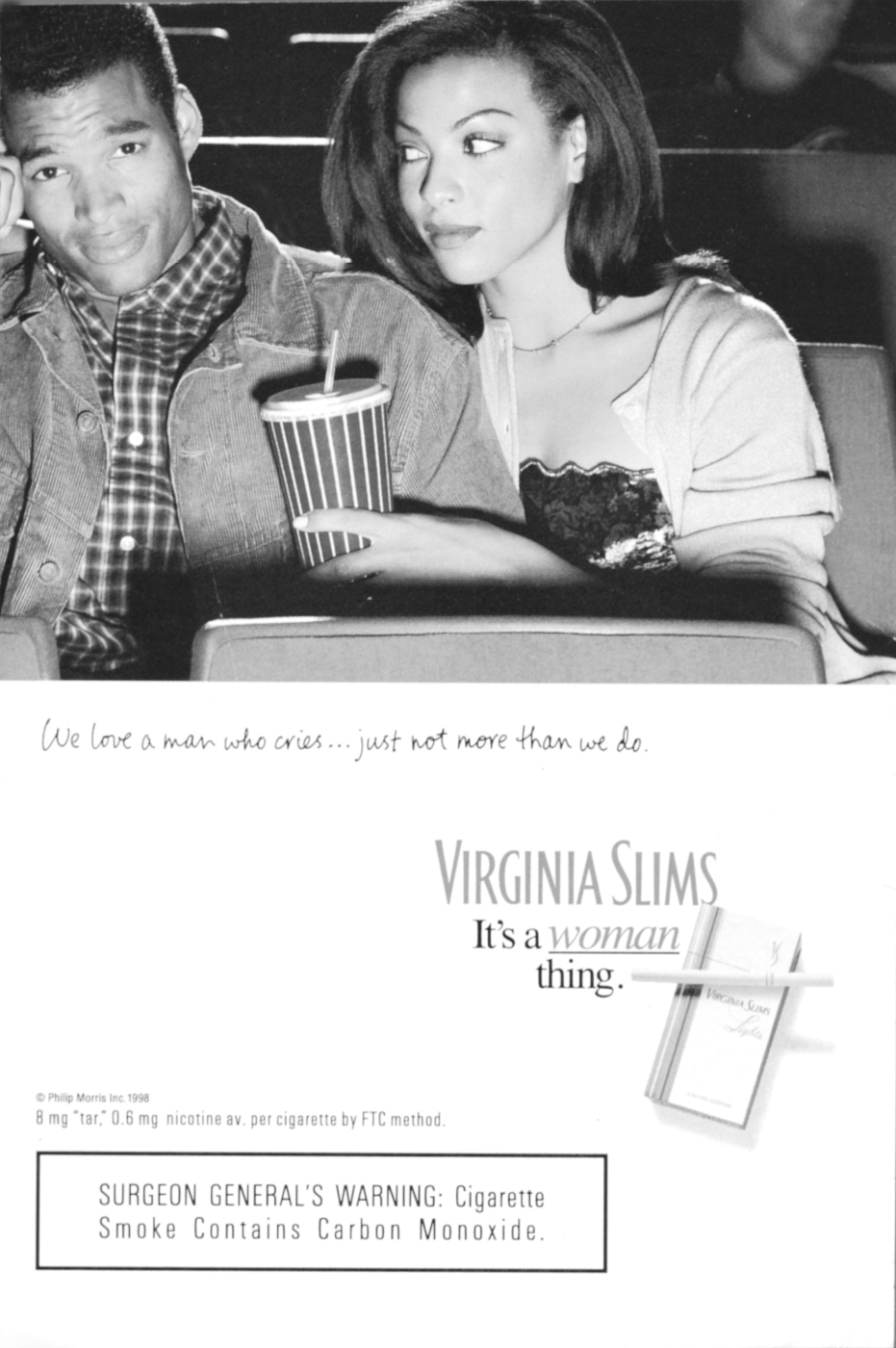

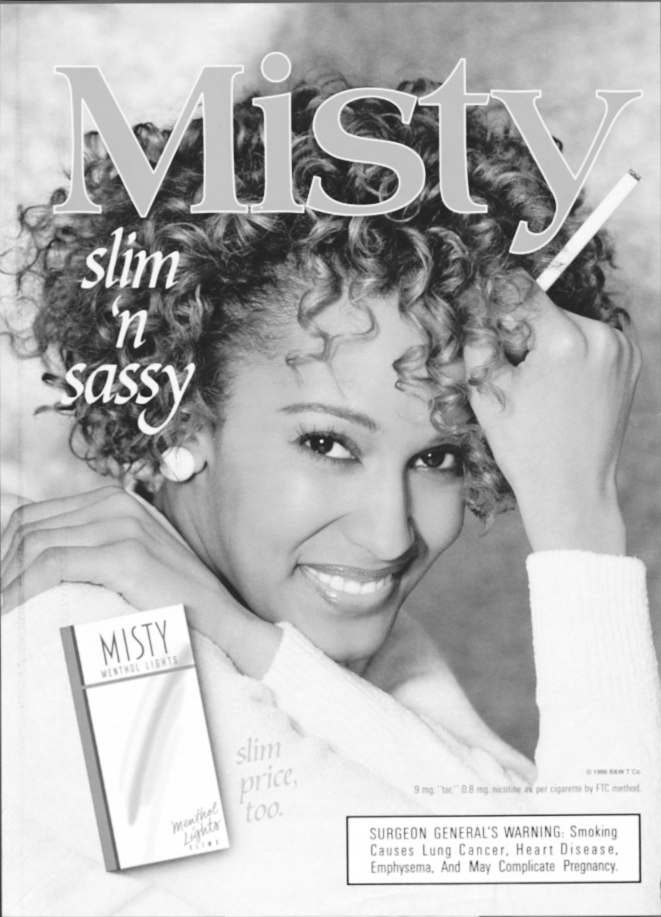

The evidence is clear that all this targeted advertising does indeed influence children. In 1968 Virginia Slims was introduced by Philip Morris. In the following six years, the number of girls ages twelve to eighteen who smoked more than doubled. There followed a proliferation of cigarettes designed exclusively for women, such as More, Now (which exploitively had the same name as the acronym for the National Organization for Women), Max, Eve, Satin, and Misty. By 1979, magazine tobacco advertisements targeting women equaled those targeted to men. These advertisements offered and continue to offer smoking to young women as a way to rebel and be cool, of course, but also as a way to control both their emotions and their weight. And, of course, advertisements offer cigarettes to everyone as a powerful symbol of sexuality.

Many ads also offer cigarettes to women as a symbol of emancipation and freedom. The co-optation of women’s liberation by the tobacco industry began in 1929 when Edward Bernays, the “father of public relations,” was hired by George Washington Hill, the president of American Tobacco, to promote cigarette smoking by women. Hill reportedly said, “It will be like opening a new gold mine right in our front yard.” Bernays did an excellent job. He persuaded some debutantes to march in the Easter Parade in New York City and to smoke Lucky Strikes, asserting that their cigarettes were “torches of freedom.” This was reported as news, rather than as an advertising campaign.

Bernays did not create the link between cigarette smoking and emancipation for women, but he certainly exploited it. The cigarette was a symbol of liberation and independence for women in the 1920s for many political and cultural reasons. However, advertising did a great deal to legitimize, normalize, and promote this connection. In 1929 Lucky Strike ran a preposterous ad headlined “An ancient prejudice has been removed,” which compared prejudice against women to prejudice against smoking. The copy said, “Today, legally, politically and socially, womanhood stands in her true light. AMERICAN INTELLIGENCE has cast aside the ancient prejudice that held her to be inferior,” and continued, “Gone is that ancient prejudice against cigarettes.”

Women took up smoking in greater and greater numbers. Today 25 million American women and one out of every four girls under the age of eighteen smoke. The highest rates are among whites and Native Americans, and the lowest are among African-Americans and Asians. Lesbian and bisexual rates are almost double those of the general population. Given all the billboards and tennis tournaments and fashion catalogs and other ploys designed to glamorize smoking by women, it is hard to imagine that less than a century ago it was taboo.

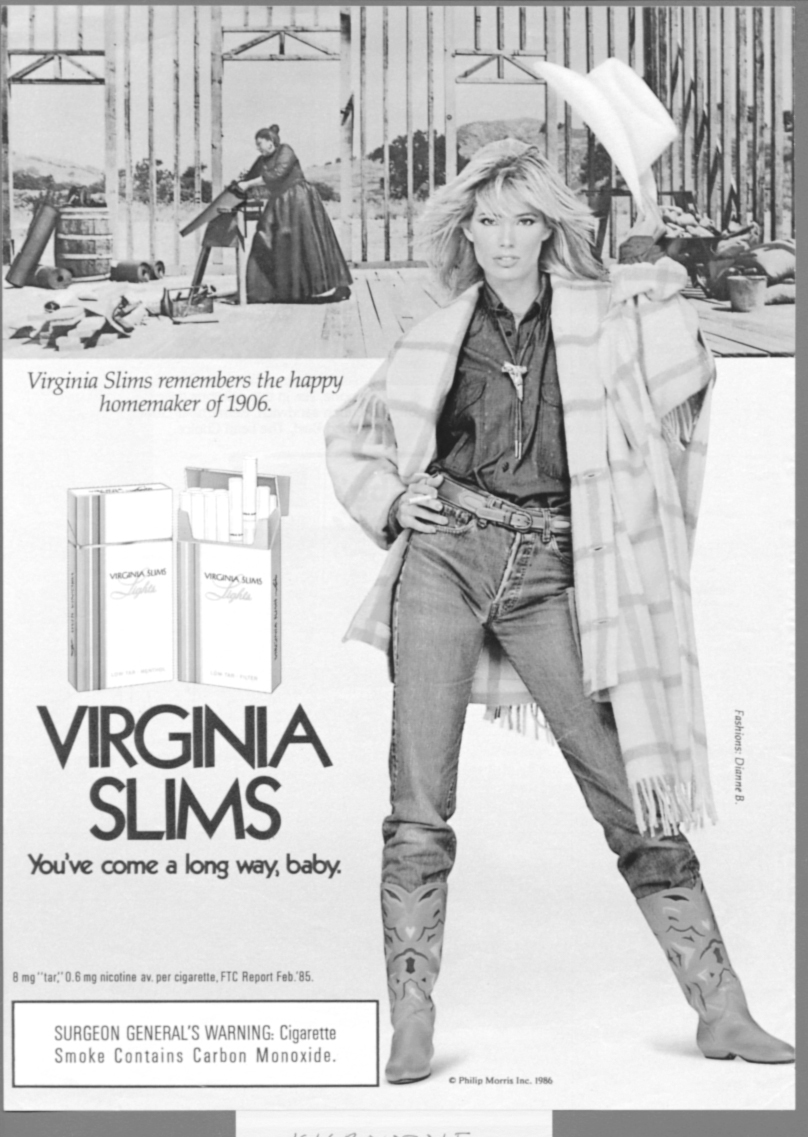

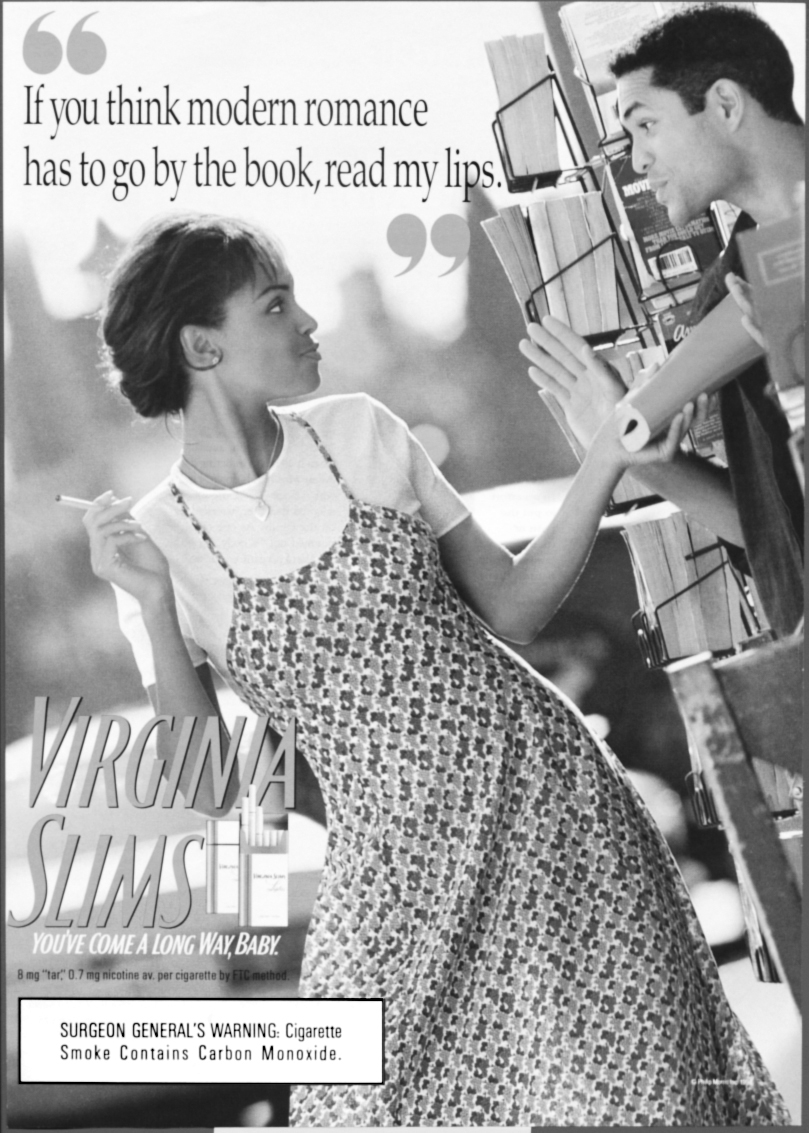

The insidious link between cigarette smoking and liberation and independence that Bernays promoted and exploited reached its nadir in the Virginia Slims campaign with its trivializing slogan, “You’ve come a long way, baby.” This equation between liberation and addiction, between freedom and enslavement to tobacco, is particularly ironic, given that nicotine is the most addictive drug of all.

The truth about cigarette smoking is that most smokers wish they could quit. A whole new industry has been founded on the fact that this is often extremely difficult. Surely any intelligent person looking at the barrage of ads for nicotine patches and nicotine chewing gum (one of which promises to relieve “the agony of quitting”) must conclude that smoking is more about enslavement than free will. According to tobacco industry documents, tobacco companies used coercion and economic intimidation to muffle aggressive antismoking messages by the makers of cessation products. And, of course, the ads (and the tobacco industry in its public-relations campaign) continue to tell us that smoking is a symbol of our freedom, of our right to choose. This is an example of the Big Lie—if you tell an outrageous lie often enough and powerfully enough, many people will come to believe it or at least tacitly to accept it as true.

The only equality with men the advent of women’s smoking has given us is that we now are getting lung cancer at the same rate. In the past twenty years, lung cancer in women has increased nationwide by more than 400 percent, surpassing breast cancer as the leading cancer killer of women. In fact, as is the case with alcohol, smoking seems to exact a heavier toll on women than on men. Smoking only a few cigarettes a day can permanently stunt lung development in girls, whereas boys are less affected. Premature wrinkling and aging of the skin due to smoking also affects women more than men. Smoking increases a woman’s chance of heart disease two to six times, her chance of lung cancer two to six times, and doubles her chances of cervical cancer. One can only consider cigarette smoking liberating if one considers death the ultimate freedom.

I was thirteen when I had my first cigarette. My friend Deedee smoked and I thought she looked very cool and mature. I was lonely and depressed. Although I did very well in school, I felt awkward and self-conscious (like every other thirteen-year-old!), dressed badly, and had very low self-esteem. I was almost completely numb from the effort it took not to feel how much I missed my mother. “In grief the world becomes poor and empty,” wrote Freud in Mourning and Melancholia. Cigarettes seemed to help fill the emptiness I felt. I choked on my first few cigarettes, of course, but I also liked the way they made me feel—high and calm at the same time.

I also thought smoking improved my image. I got straight As on my report card throughout my school years and many of my peers thought of me as a goody-two-shoes. I wanted them to see that I had a wild and rebellious streak, that I wasn’t as straight-arrow as I seemed. I had absorbed the message of the culture that girls who smoked were wild and sexy and I wanted that image for myself. At the same time, I was frightened by my sexual feelings and by the way boys were beginning to respond to me. I felt more confident with a cigarette in my hand and it also helped me to avoid being touched or kissed.

I didn’t become addicted to cigarettes because of advertising. However, I became addicted in a climate in which cigarette smoking was constantly glamorized (in films and television programs as well as in ads) and was assumed to be safe and socially desirable. In addition, I became addicted when there were no health warnings of any kind, partly because of the influence of the tobacco industry on the medical world (in those days, the American Medical Association owned tobacco stocks) and on the media. There were no programs in school—indeed many of my teachers smoked. I was thirteen years old, genetically at risk for both nicotine and alcohol addiction, and dangerously depressed. Was I responsible for my addiction? I don’t think so. However, I certainly was responsible for quitting once I learned the truth.

It is not at all unusual that depression led me to cigarettes. A heavy smoker is as much as four times more likely than normal to have a history of major depression. One 1997 study found that teenage smokers were twice as likely as nonsmokers to suffer from depression and another that teenage smokers were twice as likely to report a suicide attempt. Studies suggest that a genetic makeup that raises the risk of depression may also raise the risk of nicotine addiction. Depressed smokers also find it harder to quit than average. These days, as more and more people quit smoking, those who start and who are unable to quit are increasingly those who are depressed. One middle-school girl, a participant in a series of roundtable discussions run by the Commission for a Healthy New York, said, “Smoke fills you up when you feel empty inside.” And a woman in an unhappy marriage said, “Smoking helped to dampen things down. When it got to the stage when I couldn’t bear it any longer, I found if I lit up a cigarette it helped to get me over the next five minutes. It gave me enough breathing space to stop the endless crying, and carry on with whatever had to be done.”

Worldwide cross-cultural studies reveal that depression and anxiety disorders are two to three times more common in women than in men. This seems to be increasingly true for young women. A 1997 nationwide survey of college freshmen found that one in eight freshmen women reported frequently feeling depressed, contrasted with one in ten a decade ago.

Women are also more likely than men to use cigarettes, food, alcohol, and other drugs to deal with stress and depression and negative feelings, such as anxiety, nervousness, and especially anger. Depressed women are also more likely than depressed men to eat, smoke, and blame themselves, whereas men are more likely to become aggressive, to isolate, or to engage in sexual behavior.

Some studies indicate that women experience greater anxiety than men when they attempt to quit and seem to have a higher rate of relapse. Although this could be at least partially due to weight gain or premenstrual stress, several researchers, including myself, believe that it is women’s use of cigarettes to cope with negative feelings, especially anger, that makes it easier for women both to start smoking and to relapse. This theory is supported by the fact that women are more likely to relapse in situations involving negative emotions, such as anger and stress, whereas men relapse more often in positive situations such as social events.

According to Dr. Teresa Bernardez of Michigan State University, “Anger and the attempts to eradicate it are responsible for most of the symptoms and dysfunctional behaviors that women present nowadays: from depression to inhibition of action and creativity, from apathy to disturbances in sexual behavior.” She and many other therapists agree that powerful social and psychological forces combine to keep women from expressing anger and even from admitting that they feel it.

An angry woman is still often considered terribly unfeminine and undesirable. She is likely to be labeled “strident” or “bitchy,” terms never applied to angry men. Since anger is one of the great taboos for women, we learn to repress anger, and usually to turn it against the self. This process occurs with all oppressed people and has been well-documented. Anyone who has been abused in childhood—sexually, physically, or emotionally—is bound to feel enormous rage, although it may not be conscious.

What to do with all that rage (or, if it has been thoroughly repressed, all that depression)? Why not have a cigarette or another piece of cake? Perhaps one of the reasons it is so difficult for women to quit smoking is that smoking becomes so inextricably linked with suppressed anger. “Stifle yourself,” Archie Bunker used to say to his wife Edith whenever she got upset or angry. What better way to stifle oneself than to stuff a cigarette or some food into one’s mouth? It is one of the few things one can do with all that anger and frustration that is socially acceptable for women.

Women who are doubly or triply oppressed (by their color, socioeconomic status, educational level, or sexual orientation) have higher rates of depression than do middle- to upper-middle-class heterosexual white women) and are even more likely to use cigarettes to deal with negative emotions. When people are overwhelmed by poverty, violence, and crime, it is understandably difficult for them to take the long-term health risks of smoking seriously. In Straight, No Chaser: How I Became a Grown-up Black Woman, Jill Nelson writes about the rage that results from being black and female in a culture that despises both: “We turn our rage inward and wreak it on ourselves; we drink too much, eat too much, inhale drugs in an effort to beat back the pain and rage.”

As Nelson says, suppressed anger also plays an important role in alcoholism and in eating disorders. Jennifer, a fourteen-year-old anorexic, said, “Well, my anorexia is where I put my feelings . . . especially the angry ones.” And Bone, the abused girl in Dorothy Allison’s powerful novel Bastard Out of Carolina, says, “It was hunger I felt then, raw and terrible, a shaking deep down inside me, as if my rage had used up everything I had ever eaten.”

A study reported by British researcher Bobbie Jacobson in her groundbreaking 1982 book The Ladykillers: Why Smoking Is a Feminist Issue found that women smoked more when they felt “uncomfortable or upset about something” or when they were “angry, ashamed or embarrassed about something” or when they wanted to “take their mind off cares and worries.” Canadian researcher Lorraine Greaves found that many women smoked in order to blunt their emotional responses, to quell and suppress both feelings and comments. Some of the women described “sucking back their anger.”

An article called “Why Smoking is a Real Drag” in the January 1998 issue of Teen magazine begins with the story of a girl named Lauren who had a huge fight with her best friend on a Saturday night:

Lauren was pissed. She slammed the phone down, headed out the front door, sat on the front steps—and lit a cigarette. “It calms me down and helps me think,” Lauren says of her smoking habit. “After I had a cigarette, I was able to go back inside, call my friend and work everything out. If I hadn’t had one, I probably would have called her back and yelled and screamed, and it would have been a horrible night. Having a cigarette helps me control my emotions. My problems are still there, but the tension is gone.”

So a cigarette saved Lauren’s Saturday night. But at what price? Addiction to a drug that can cause cancer and heart disease. In other words, kills.

This strikes me as a mixed message at best (not surprising, of course, given the dependence of the media on the goodwill of the tobacco industry). I can’t help thinking that, if I were a teenager, saving a friendship in the here and now would be worth a whole lot more than avoiding cancer and heart disease in forty or fifty years.

Cigarette advertisers have long been aware of the fact that women are especially likely to use smoking as a way to regulate our moods and cope with negative feelings. A 1949 Lucky Strike ad says, “Smoke a Lucky to feel your level best,” and continues, “Luckies’ fine tobacco picks you up when you’re low . . . and calms you down when you’re tense.” (The model in the ad is Janet Sackman, seventeen years old at the time, who was urged by tobacco executives to smoke in order to be more “real” in the ad. She became addicted. Years later she developed throat cancer and lung cancer and had to have her voice box removed. Today she is an admirable and compelling figure in the anti-tobacco-industry movement.)

A 1951 Marlboro ad features a worried-looking baby saying, “Before you scold me, Mom . . . maybe you’d better light up a Marlboro.” Another ad from the 1950s features a woman clearly at her wit’s end being handed a cigarette by her husband. The copy says, “When Junior’s fighting rates a scold … Why be irritated? Light an Old Gold.” Women have long been encouraged by men, their doctors as well as their husbands and boyfriends, to use drugs to deal with negative feelings, to “calm down.” Cigarettes offer a small, controllable sense of comfort while warding off a potentially dangerous outburst of emotion.

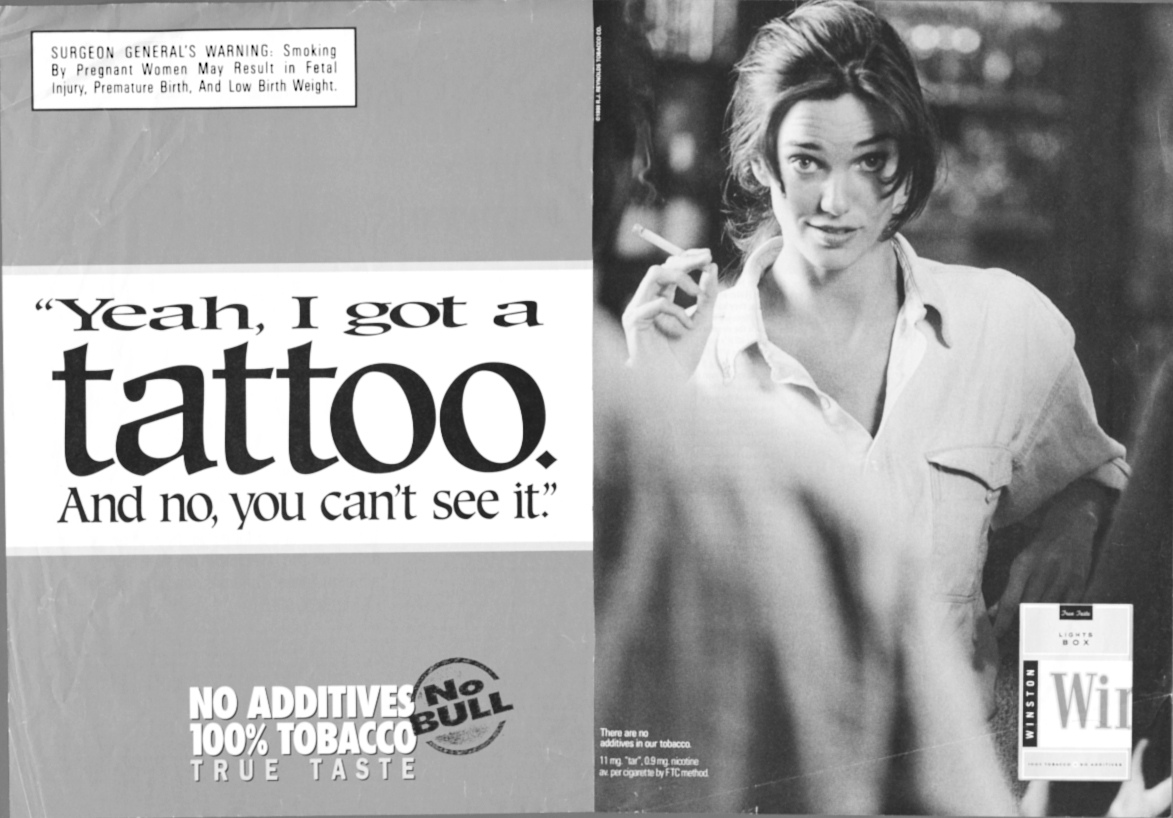

“I get enough bull at work. I don’t need to smoke it,” says a young woman in one of the ads in Winston’s “No Bull” campaign. “I’m a damn good waitress,” says another young woman in a Winston ad, “If you want an actress, go see a movie.” The lower one’s socioeconomic level, the more likely one is to smoke, so these women may well get a lot of bull at work. However, the solution, according to this campaign is to have a cigarette rather than to confront their bosses or take some constructive action (such as joining a union or going back to school and getting a better job). People in these kinds of jobs don’t smoke because they are stupid, however. They smoke to relieve the tedium of the work, to be doing one small thing seemingly for themselves. I’ve had many jobs so soul-crushingly boring that cigarette breaks were the highlight of my day. As Barbara Ehrenreich said, “I don’t know why the antismoking crusaders have never grasped the element of defiant self-nurturance that makes the habit so endearing to its victims—as if, in the American workplace, the only thing people have to call their own is the tumors they are nourishing and the spare moments they devote to feeding them.”

Some of the “antismoking crusaders” may not have grasped this, but the tobacco industry certainly has. It has known for a long time that cigarettes are often used as a way to deal with boredom at work, a way to add a little pseudo-excitement to one’s life. In the 1930s a cigarette ad featuring a woman interrupting her knitting by pulling a cigarette from a Chesterfield pack said:

To knit and spin was not much fun

When ‘twas my sole employment

But now I smoke these Chesterfields

And find it real enjoyment

“Five more smokes for the long working day,” proclaims a Marlboro ad. One of Satin’s slogans was “Don’t let anything ever be ordinary.” “Flavor happens,” says an ad for Merit. The copy continues, “Nothing’s happening. You’re bored. You try a Merit Ultra Light. WHOA! You’re getting real flavor from an ultra low tar cigarette! You light up another Merit. WHAT THE? It happens again.”

Nicotine is quite an amazing drug because it perks one up in times of boredom and calms one down in times of stress. Most smokers use cigarettes both to relax and to cope with crises. Stress is related to powerlessness, to feeling that one has little or no control. Thus the most stressful jobs are those in which people have the least power. Nurses are far more stressed than doctors (and far more likely to smoke). Secretaries are usually more stressed than their bosses. It is no coincidence that people in low-level jobs, people who are or feel powerless, are much more likely to smoke than those with high-level, high-income jobs.

One of the most stressful and at the same time most tedious jobs of all is to be at home with small children. There are great rewards as well, but anyone who is honest must admit that there are times of feeling anxious, bored, and almost completely out of control. People in these situations, almost always women, are often desperate for personal time, for “space.”

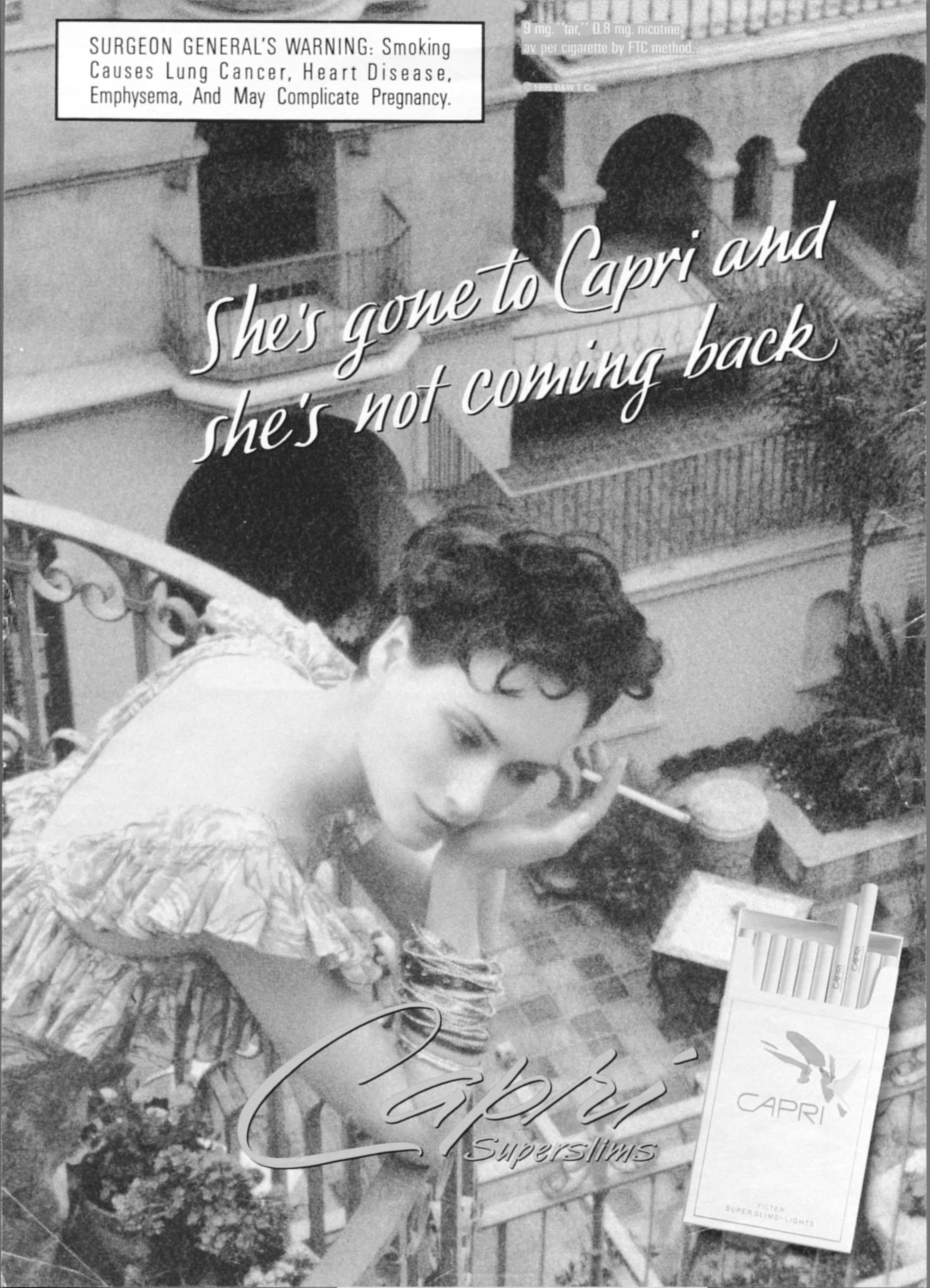

And many cigarette ads offer them just this. “It’s a few minutes of your own” was the slogan for Eve cigarettes in the early 1990s. “Peace & Quiet,” says one of the ads in a Benson & Hedges campaign, which features a cigarette curled up on a couch. “She’s gone to Capri and she’s not coming back,” says a cigarette campaign targeting women (perhaps a rare example of truth in advertising). The addiction becomes a place one can escape to, clearly alluding to the mind-altering properties of the drug.

Given that the tobacco industry knows that smokers, especially women, use cigarettes to cope with stress and anger, wouldn’t it be brilliant of them to design a cigarette campaign that seems to offer freedom and liberation to women but that in fact, on an unconscious level, triggers depression and anger—and then offers the cigarette as the solution? This is exactly what the long-running Virginia Slims campaign has done.

For years this campaign usually featured a slim happy young woman in the foreground and a sepia-toned, pseudo-antique photograph in the background depicting those dark, dismal days when women were oppressed—back before we had our own cigarette. In a subtle way, however, the ads remind us that things really haven’t changed that much. Although the model seemingly is proclaiming that she is liberated, her pose, dress, makeup, and demeanor are always stereotypically feminine in a “cute,” strictly ornamental way. There is never a hint of any real freedom from traditional roles and limitations. The model is never shown doing anything but laughing, holding a cigarette, and wearing stylish clothes. She is never working or in any way demonstrating her liberation and independence. And she’s still a “baby.”

In one of the old photographs, a woman, certainly overweight by today’s standards, is building a home. The copy says, “Virginia Slims remembers the happy homemaker of 1906.” It is ironic that it is the benighted woman of the past who is working at “a man’s job,” whereas the liberated modern woman is doing nothing but holding her cigarette.

Even more telling, the old photographs depict a world that seems long ago on the surface—but is disturbingly the same when examined more closely. “Equal pay for equal work,” an ad tells us, and we laugh at the old photograph of the man patting both his wife’s and his dog’s heads. Yet women still don’t get equal pay for equal work—and nowhere near equal pay for comparable work. The more things change, the more they stay the same. What effect does this have? I think it reminds us, on an unconscious level, that we have not come such a long way, after all. This is depressing. This arouses anxiety. Perhaps it makes us reach for the comfort of our cigarettes.

Another way that many of the Virginia Slims ads arouse anxiety is by portraying violence against women. Although always presented as a joke, the violence is not really so funny when one pays attention to it. One ad features an old photograph of a woman being hit by a figure in a clock tower and the caption, “In 1903 Naomi Fett couldn’t understand why more women didn’t sneak cigarettes in the Emperor’s clock. A moment later it struck her.”

Women are dragged behind horses, shot from rockets. Often they are in literal bondage. These are caricatures, meant to be funny, but too close to the reality of many women to be really funny. The ads feature scenes of humiliation, abandonment, subordination, very real themes still in many women’s lives—but always as jokes.

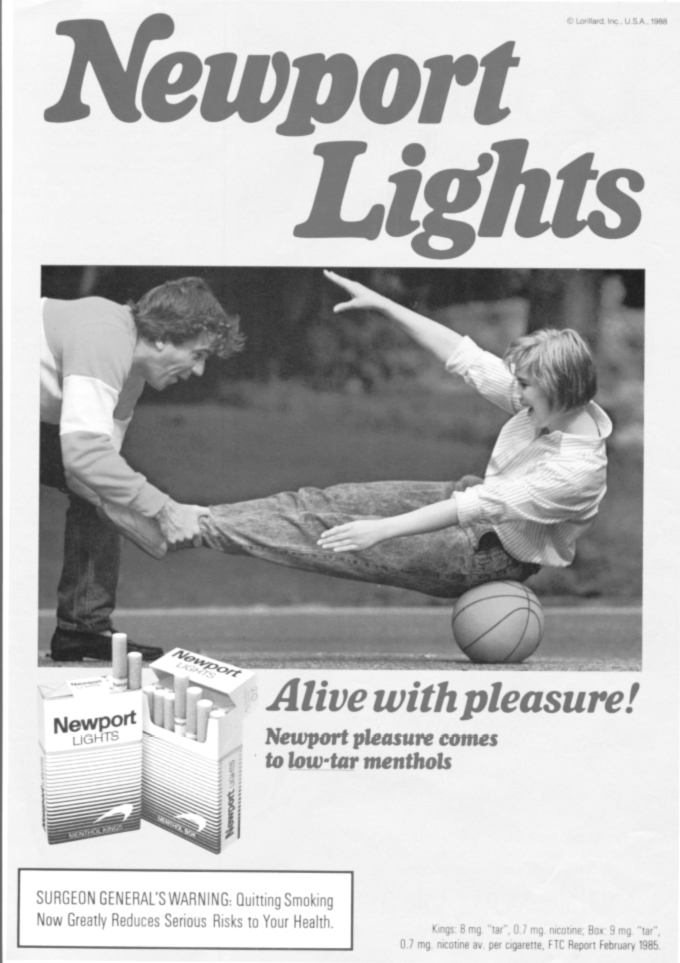

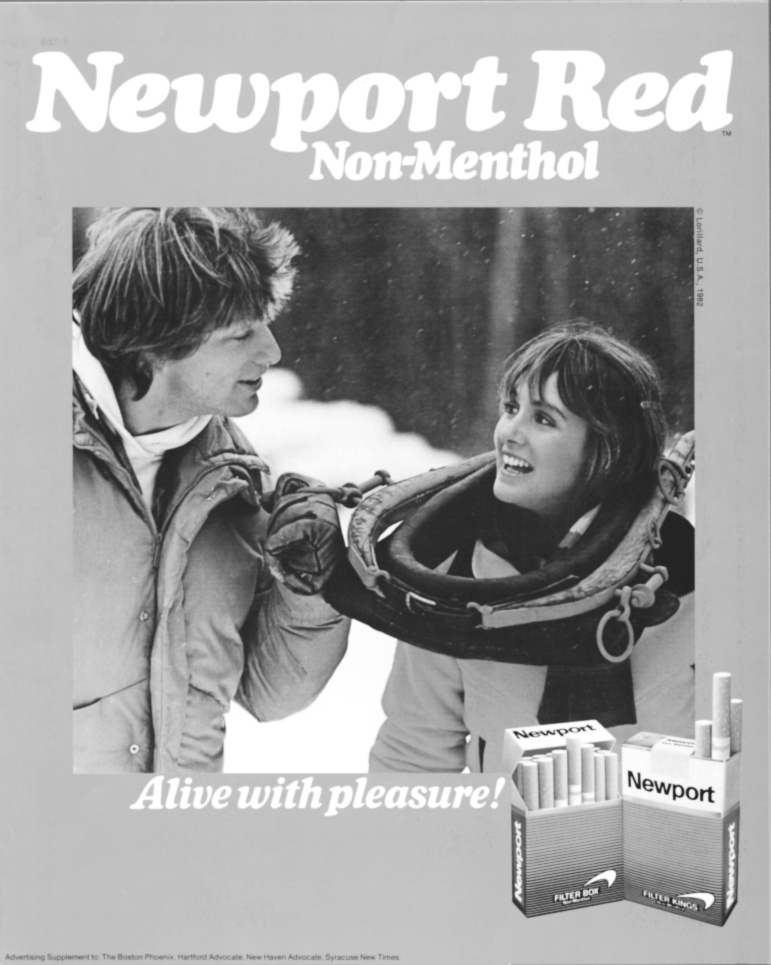

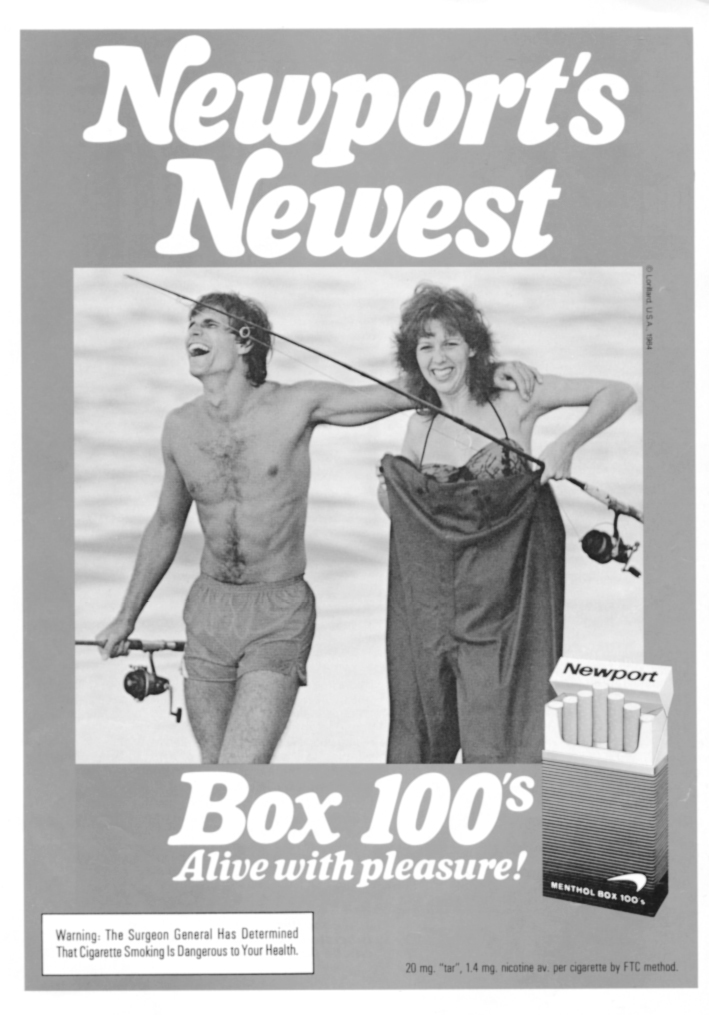

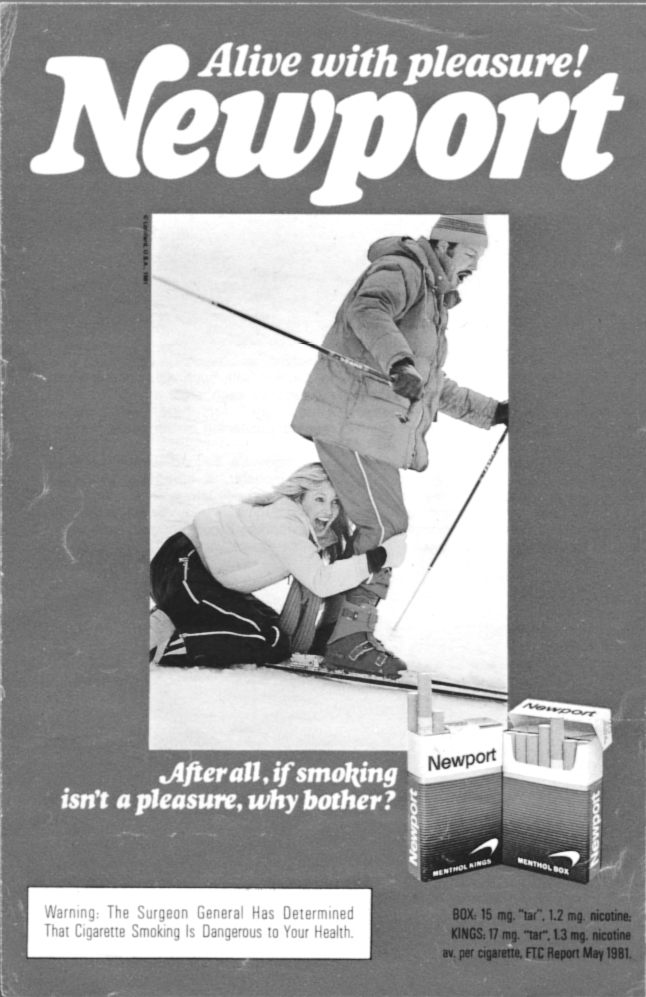

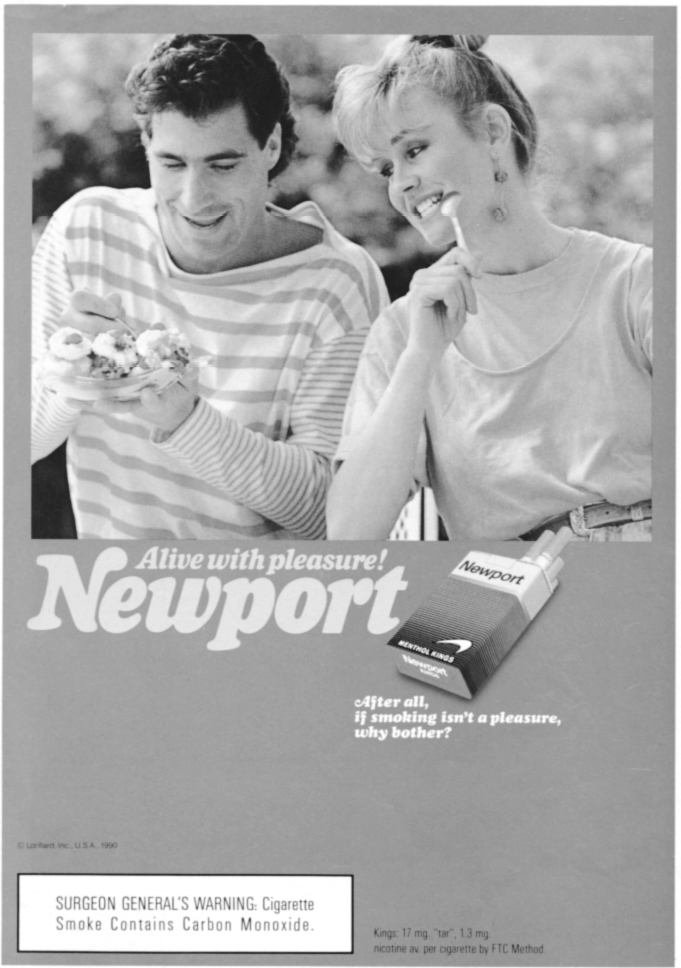

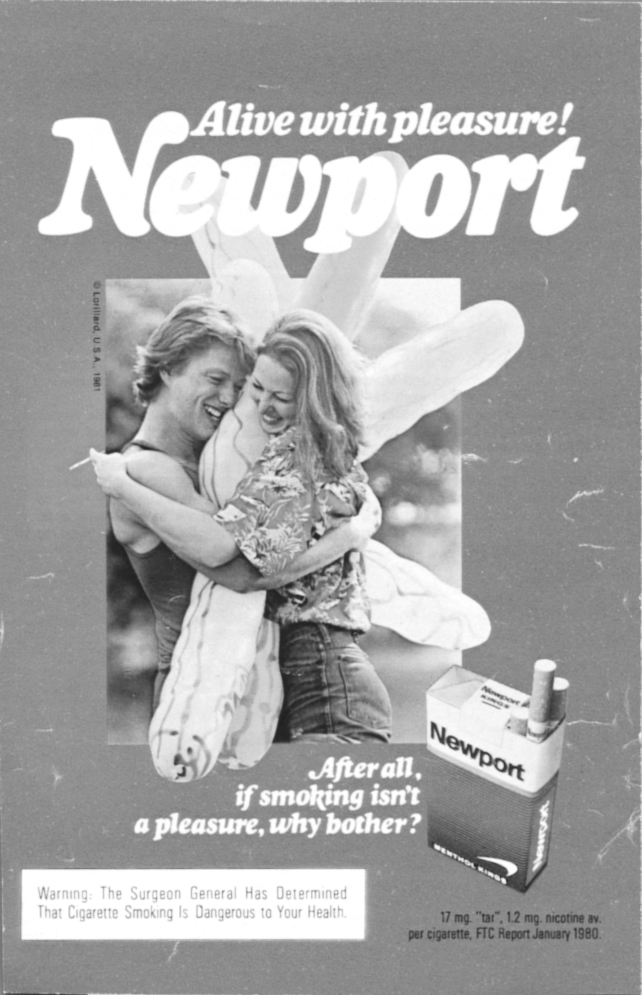

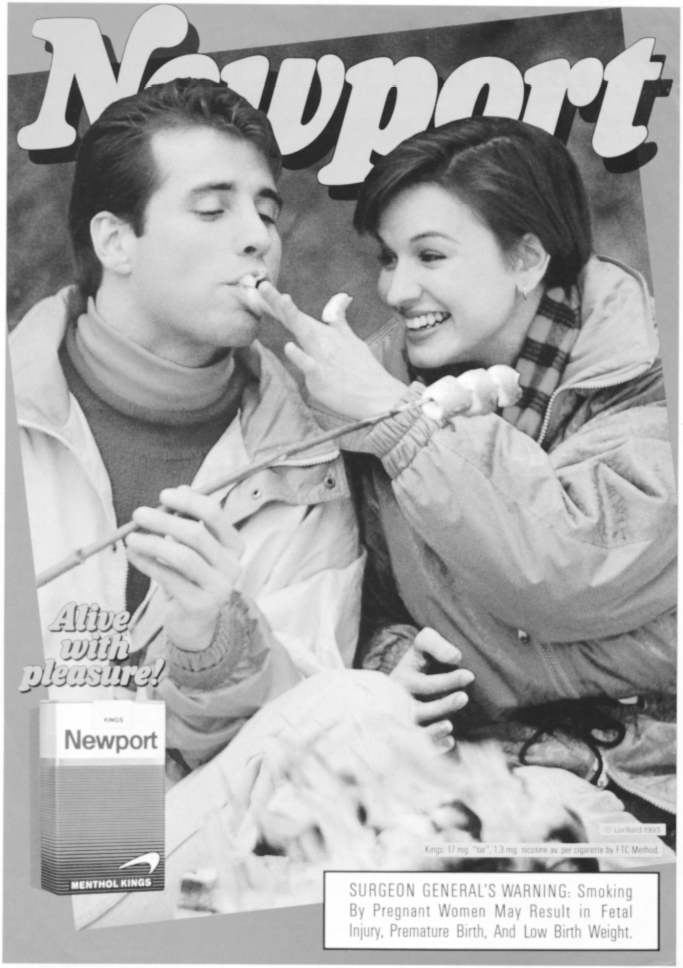

Certainly the cigarette advertisers, like the food and diet product advertisers who also spend billions on psychological research, are aware of suppressed anger in women and deliberately play upon it in their advertising. The advertisers also reflect some of the deeper issues of the culture regarding power and freedom for women. It is difficult, if not impossible, to know how much is conscious and calculated. However, another cigarette campaign seems to do very much the same thing as the Virginia Slims campaign—to turn an anxiety-producing situation, especially for women, into a joke. For years a Newport campaign featured young men and women in playful caricatures of essentially violent situations. I first noticed this about twenty years ago and was astonished when I looked at the ads one after another. The campaign has obviously been very successful—similar ads continue to run and Newport is one of the top cigarette brands.

Many of the ads are shockingly violent, especially when seen as a group. Women are buried in snow, stuffed into boxes, thrown over men’s shoulders, tied to poles, hit with snowballs, bells, a barrel of leaves, cymbals, buckets of water, and pillows. In one ad, a woman seems to be on fire. In another, a woman is seated on a basketball, about to fall onto hard pavement. Another features a woman about to be submerged in icy water, her face an odd mix of joy and terror. Perhaps the strangest one of all features a woman in a yoke, such as is used on oxen.

In others, women are teased, made to seem weak and inferior, ridiculous. A man derisively laughs while testing the biceps of a woman ludicrously dressed in a man’s football jersey. Another man howls with laughter as a woman wears fishing pants far too big for her and awkwardly carries a fishing pole (try as a woman might to wear the pants and have a penis, she just can’t get it right). A woman on her knees grabs onto a man who is skiing (she just doesn’t have the right equipment—the right pole, to be exact). Another woman grabs a man on skates. In one ad a woman’s head is covered with a paper bag and in another she is hobbled and blindfolded in a sleeping bag.

Occasionally, other cigarette ads play on the theme of violence against women. An ad for Camels advises young men at the beach to “Run into the water, grab someone and drag her back to shore as if you’ve saved her from drowning. The more she kicks and screams, the better.”

While women are threatened with violence, men are sometimes portrayed as fools. One Virginia Slims ad says, “A deck of cards where the only men are jokers? How appropriate.” When psychologist Judith Jordan asked a group of women what they most feared from men, the women replied, “That they will hurt us.” When men were asked the same question about women, they replied, “That they will laugh at us.” There’s a world of difference, of course, between being hurt and being ridiculed, but either one can arouse anxiety—which, in turn, can make smokers reach for their cigarettes.

Newport targets men as well as women, of course, so the ads sometimes trigger male anxiety. Several ads show men, often African-American men, in ludicrous positions. In one such ad, the man has the head of a jackass. In another, he has the body of a fat woman in a tutu. In yet another, two men are dancing in hula skirts. As is often the case, the quickest way to ridicule a man is to present him as a woman. A man with balloons or socks stuffed into his shirt is seen as hilarious—not so a woman with a balloon stuffed in her pants.

Sometimes the woman is presented as potentially threatening. In one a woman is cutting a man’s pants into shorts, the scissors precariously close to his crotch. In another, she is shaving him, the razor poised against his throat. In yet another, she seems to be executing him with her hair drier, blowing his brains out. Thus the Newport campaign, like the Virginia Slims campaign, arouses unconscious anger and anxiety and offers the cigarette as a solution.

As audiences have become more sophisticated, cigarette ads have become more subtle. For a couple of years after Virginia Slims stopped using the old photographs, their ads featured a thin, beautiful young woman confidently asserting herself. “Management with style . . . obviously my strong suit,” says one. “What do you call a take-charge woman? How ‘bout boss?” says another. A woman perched on a motorcycle says, “I don’t necessarily want to run the world, but I wouldn’t mind taking it for a ride.”

A few of the ads use the beautiful women to downplay the importance of looks. “Beauty without brains is just window dressing,” says one, featuring two beautiful women (one wearing glasses, however, such an original way to indicate that a woman is intelligent) and a mannequin. “Judge me on looks? You’re just scratching the surface,” says another.

Of course, it is not surprising that advertisers would use beautiful, independent, confident women to sell their products. What’s the problem? The problem is the dissonance between the image in the ads and the reality of many female smokers’ lives—and the implicit promise that smoking will somehow resolve this dissonance. A typical woman smoker is young (or became addicted while very young), depressed, and stuck in a dead-end job or life and perhaps in a violent relationship as well. She is far from taking the world for a ride. Cigarettes won’t help, to say the least.

The Commission for a Healthy New York study found that girls saw smoking not only as a way to deal with nervousness, to control appetite, and to look older, but also as a way to create a tougher image and to rebel against a boyfriend. Certainly cigarettes give a girl a tougher image. A cigarette (or a cigar these days) is an instant symbol in many films and situations to indicate that a woman is strong-willed and defiant. An ad for Buffalo jeans features a beautiful young woman holding a cigar. The copy says, “My boss says I shouldn’t smoke so I quit.” The implication, of course, is that she refused to be told what to do and quit her job. She seems quite arrogant, but she is biting her lip and her breasts are almost completely exposed. Her posture is also extremely defensive. She is more vulnerable than she appears at first glance.

Perhaps the girls most susceptible to addiction are the ones who are really least tough, most vulnerable, feeling most in need of a tougher image for protection. Especially for adolescents, the tough talk, the callous image, almost always signals a terror of vulnerability within. The high-school dropout, the teenager being sexually abused at home, the pregnant teenager, the child of alcoholic and nicotine-addicted parents, the young woman being battered by her boyfriend or harassed by young men at school—all are at great risk for smoking. How appealing the Virginia Slims message must be—”A woman’s place is any place her feet will take her” and “I always take the driver’s seat. That way I’m never taken for a ride.”

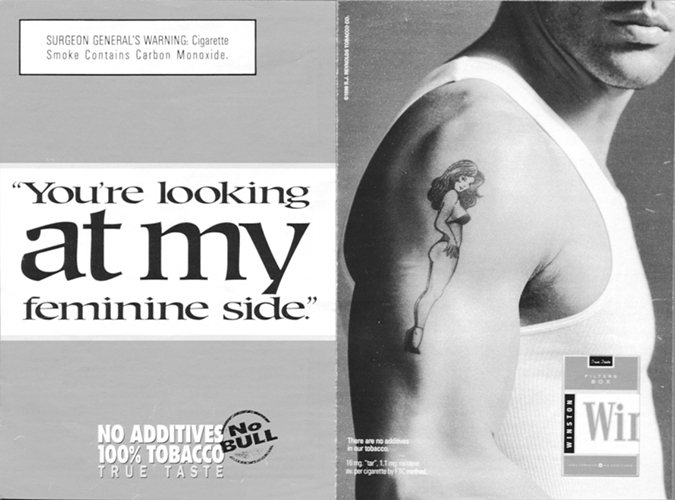

Other cigarette brands often offer a similar message. “Here’s to women who can light their own cigarette,” says a Winston ad. As if this is all it takes for a woman, especially an African-American woman, such as the one in the ad, to be powerful. “Yeah, I got a tattoo,” says a young woman in another Winston ad. “And no, you can’t see it.” She sounds tough but she looks quite vulnerable and the man standing very close to her (we see only his out-of-focus broad shoulder) is potentially threatening.

Girls and women are likely to be dominated by the men in their lives—by their lovers and the men they work for. Rather than offering models of healthy intimacy and mutual respect, advertising usually normalizes and eroticizes this domination. Lack of communication and an edge of hostility between women and men are also normalized. “To us, ‘open’ communication means when we’re talking, your eyes are open,” says a young woman in one Virginia Slims ad. “When we ask for your honest opinion,” says another, “you should know this is a trick question.” And, in yet another, an African-American woman throws back her head and laughs, while saying “Just because we laugh at your stories doesn’t mean we believe ’em for a second.”

We are often encouraged to have sexual adventures with men who are bad for us. Forget the sensitive men–“We love a man who cries, just not more than we do,” says a Virginia Slims ad, which quite obviously ridicules the man who cries. “You’re looking at my feminine side,” says a muscular man with a girlie tattoo on his biceps. Fall for the men who mistreat us, abuse us, objectify and disappoint us. “Some men are like chocolates,” says a Virginia Slims ad. “We know we shouldn’t but occasionally we just can’t help ourselves.” Of course, this is the voice of denial, no matter what the addiction—whether it be to dangerous men, alcohol, chocolates, or cigarettes.

The voice of denial tells us that we are in control of our addictions. Adolescent girls in particular want to believe that they are controlling their cigarettes rather than that their cigarettes are controlling them, and cigarette ads generally perpetuate this delusion. In most of the Virginia Slims ads, young women seem to be completely in charge. They have nothing to fear from men. They are feisty and sassy. They know exactly what they are doing. “A kiss is the only part of romance I go into with my eyes closed,” declares one woman who seems to be literally bowling over a man. In fact, they sometimes objectify and use men. “There’s nothing wrong with putting a man first as long as you enjoy the view,” says one woman coolly. “What’s the first thing we look for in a guy?” asks an ad featuring two women ogling a young man in tight jeans. “A really great . . . um . . . personality.”

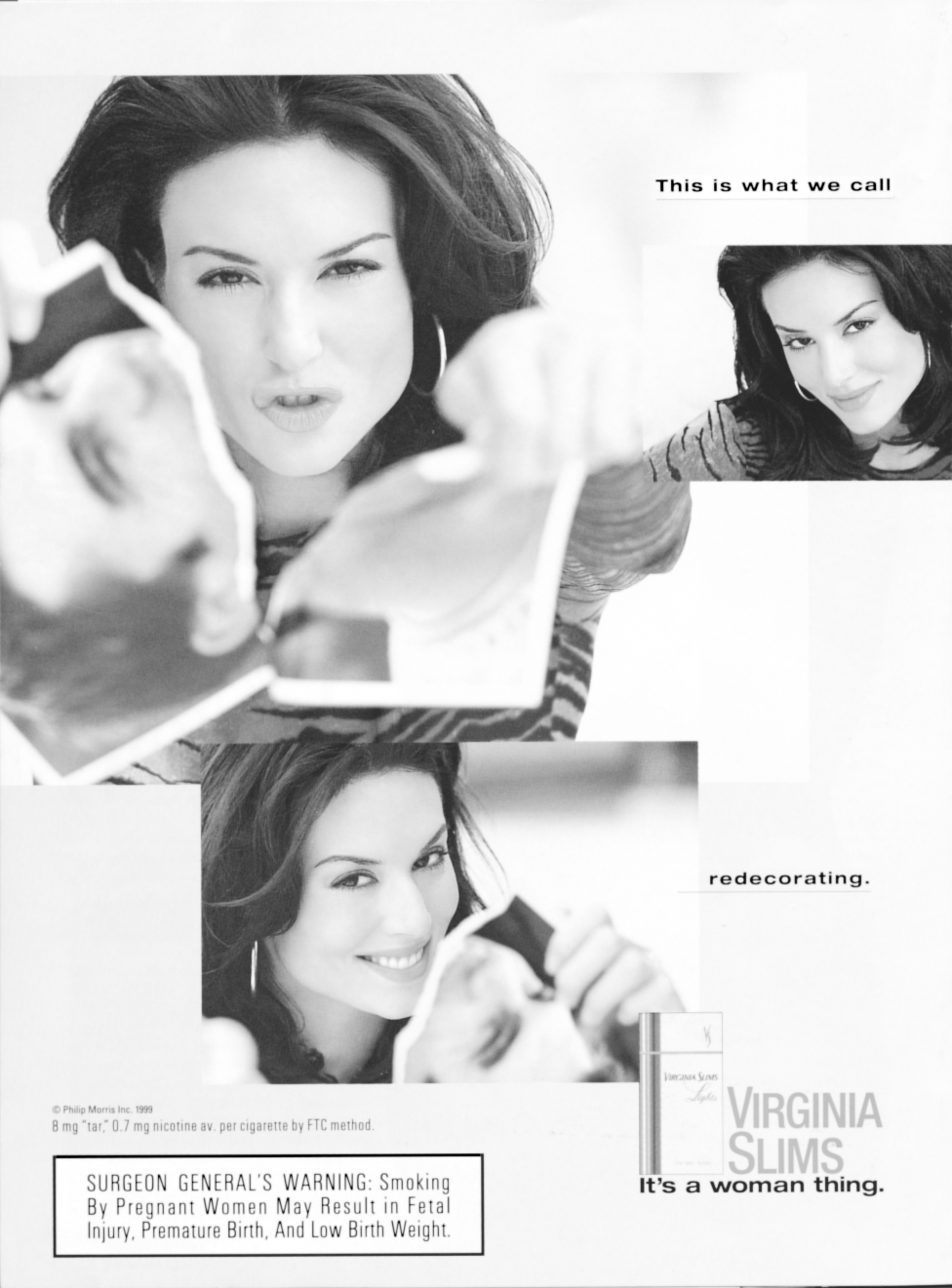

They don’t even have to fear rejection and abandonment. “This is what we call redecorating,” says a furious woman ripping up a man’s photograph. “It takes time to get over a breakup,” says a woman snuggling in a man’s arms. “Fortunately a new boyfriend can cut that time in half.” And, these ads imply, your cigarettes can help too.

These young women call the shots. “Who says you can’t make the first move?” says one ad. “Hey, if anyone tries to rein you in, just say whoa,” says an African-American woman, sitting on a fence, literally head and shoulders above her boyfriend. “Pretty in pink doesn’t make you a pushover,” says another. And yet another features a woman leading her man by the hand and the copy, “Lead the way? Yeah . . . even in 3-inch heels.” The men are all laughing, compliant, completely unthreatening. How cool these women are, how supremely confident.

And what rage there is, just below the surface. “The real reason we bring you with us to the beach is so we have some place to put the car keys,” says one woman. “Sit and wait for a phone call? Forget that number,” says another, carrying a red motorcycle helmet. “If you think modern romance has to go by the book, read my lips,” says an African-American woman while defiantly pushing a book into a man’s chest. “Who cares who wears the pants,” says a tough-looking young woman while pointing her middle finger at us.

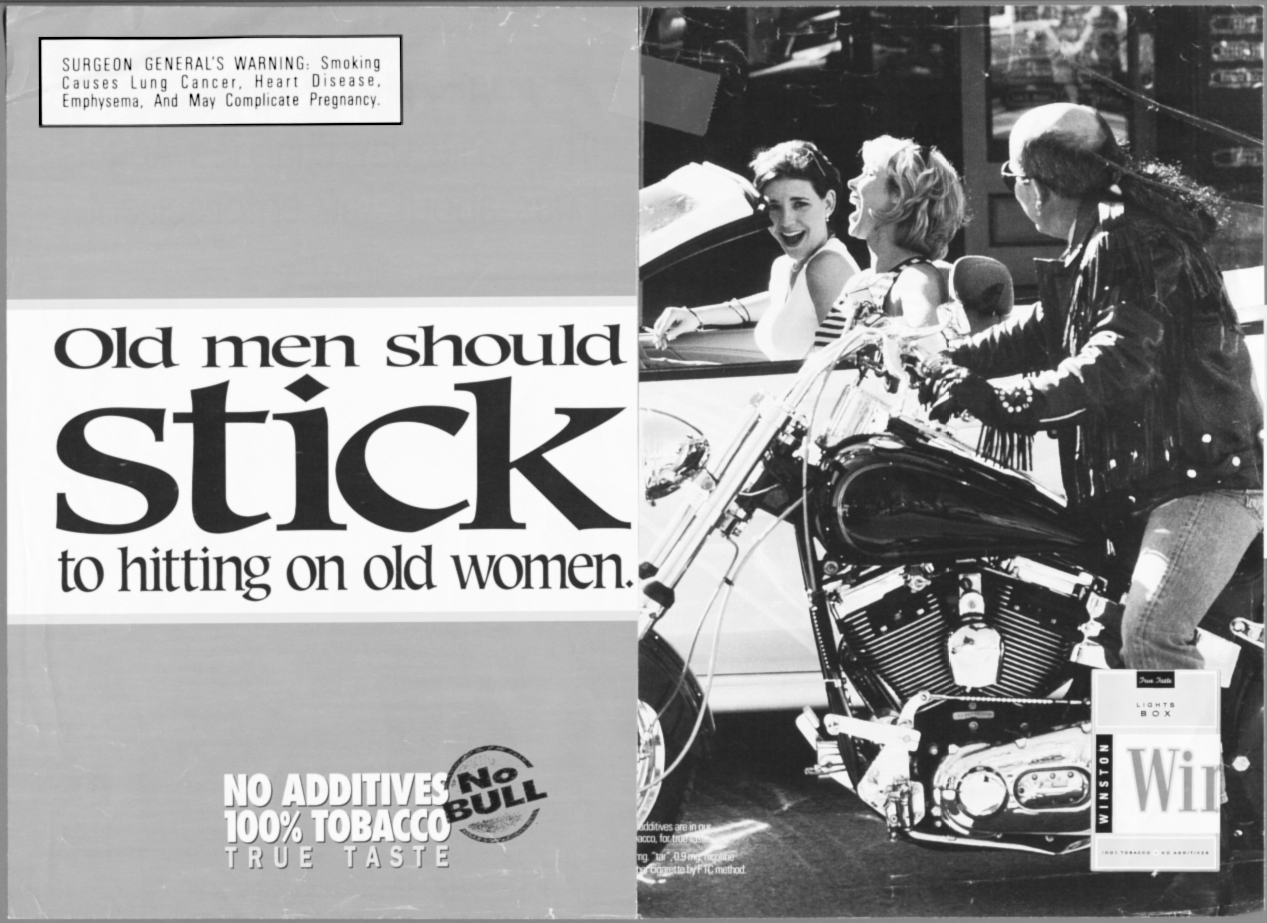

Ads for other brands also offer women cigarettes as a way to safely ridicule or express hostility to men. A 1999 Camel ad features a young woman sticking pins into a male doll while her two friends look on approvingly. Two young women in a convertible in a Winston ad laugh uproariously at a balding man on a motorcyle next to them. “Old men should stick to hitting on old women,” says the ad. Another ad in this campaign features a woman sitting beside a man with her hand over her face and the copy, “I wanted a light, not his life story.”

Many of the Virginia Slims ads feature women who are giving advice to men on how to behave. “When we ask ‘Is that what you’re wearing?’ we’re actually hoping it’s not,” says one particularly insulting version of this theme. Others feature extreme closeups of women’s faces and copy that says, “If you give us flowers, never tell us what a great deal you got on them,” “If it slices, dices or scrubs, it’s hardly ever the gift we’ve always wanted,” “If we liked being called ‘Sweetie Pie,’ we’d change our names,” and “Three words of advice when giving us a gift: save the receipt.”

However, some of the advice given is edgier, more defensive. “To us, ‘I’ll call you’ means tomorrow, not sometime before the next century,” says a woman in a bathtub, wearing bubbles and a tight smile. Others are seemingly in response to critical comments that men sometimes make about women’s appearance. “‘What did you do to your hair?’ is not our idea of a compliment,” says one. Another features a woman painting her fingernails green and the copy, “The correct answer to the question, ‘Does this look stupid on me?’ is ‘No.’”

Rather than being angry or depressed by these comments, as most real women would be, the confident women in the ads are cool and sassy. The campaign actually plays upon the anxiety that most women feel about how attractive their boyfriends and men in general will find them. We worry about looking fat and silly. Fashion is so often ridiculous that we have reason to fear looking stupid. We have the little surveyor in our head constantly criticizing us. In this campaign Virginia Slims encourages us to knock him out with a cigarette.

The campaign is also meant as a rebellious response by young women to those who criticize their smoking. I can paint my nails green, shave my head, and smoke cigarettes—whatever the hell I feel like doing, so there!

Many cigarette ads present smoking as a symbol of women’s liberation while subtly arousing feelings of anger, humiliation, and anxiety. The cigarette is the “friend” who alleviates the feelings. The cigarette allegedly helps the woman to control her feelings and thus to be like the supremely cool and confident woman in the ads. Smoking, like dieting, is offered to women as a way of being in control. However, since few if any women can be like the models and since the cigarette does not really bestow confidence and control, the overall effect of these ads is to reinforce a feeling of personal failure while seemingly addressing positive aspirations.

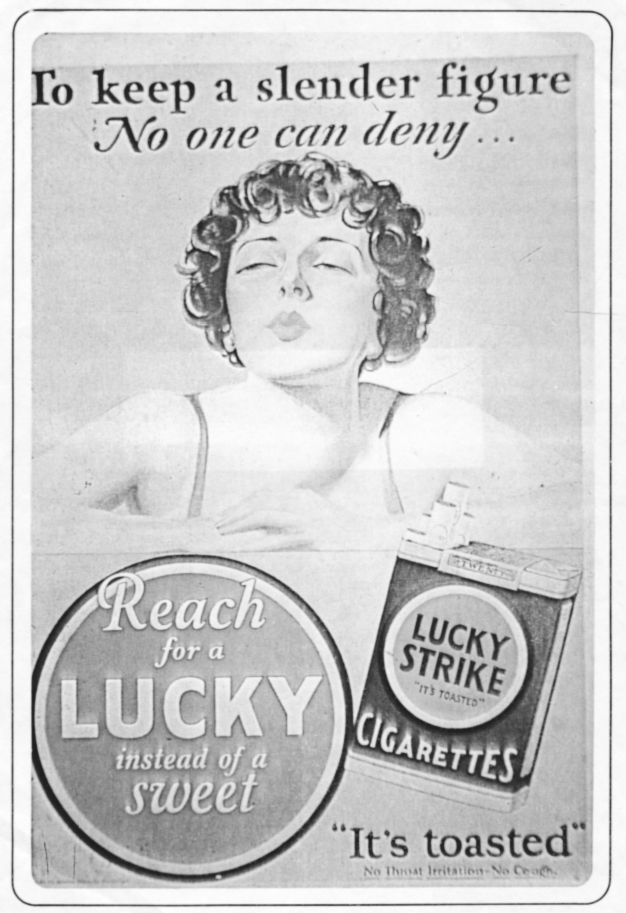

In many ways, cigarette ads offer smoking to girls and young women as a way to control their emotions. They also offer cigarettes as a way to control weight. A primary reason that many girls start smoking and women do not quit is their terror of gaining weight. Cigarette advertising has played upon this fear for a long time. In 1928 a Lucky Strike ad said, “To keep a slender figure, no one can deny . . . Reach for a Lucky instead of a sweet.” It is interesting to note how plump the model looks by today’s standards.

The tobacco industry probably couldn’t get away with such an overt message today. However, the advertisers can use extremely thin models and copy that almost always includes such words as “slim” and “slender,” such as “There’s no slimmer way to smoke” and “The slimmest slim in town” (Capri), “Very slim price” and “Slim Lights” (Newport). “Slim ’n sassy,” says the ad for Misty, thus promising girls and young women both thinness and independence with their cigarettes.

Sometimes cigarette ads have directly linked the cigarette with food. Most bizarre of all was a campaign for Kent in the early 1980s that literally put the pack or carton of cigarettes into a sandwich, a drink, a blender, a can of sardines, a box of candy, or an oyster shell and used the slogan, “The low tar that won’t leave you hungry for taste.” Newport links cigarettes with food in some of its ads too. Often a young man is eating something enormous (a huge sandwich, a stack of pancakes) while a young woman looks on. As always, a hearty appetite is considered a good thing for a man but is something to be controlled by a woman. While he eats a banana split, she gets to wistfully lick a spoon and perhaps to smoke a Newport.

Virginia Slims has played on the theme of weight control in many ways. In 1989 Superslims were introduced with the slogan “Fat smoke is history.” In 1990 the campaign featured photographs distorted to make the models seem extremely thin and elongated, as if in a fun-house mirror. And in 1994 Virginia Slims directly advertised the cigarette as a diet aid in an ad featuring a thin woman waving away a plate of food, while holding a cigarette. The copy says, “If I ran the world, calories wouldn’t count.” The implication is clear that calories do count and that girls and women should use cigarettes to resist the temptation of eating.

More recently, in the face of extensive criticism of tobacco advertising, the link with weight control has been a bit more subtle. It is still clearly made, however, in ads such as one in which a young woman says, “When we’re wearing a bathing suit, there’s no such thing as constructive criticism.” Note how this normalizes female anxiety about our bodies, our weight. The woman in the ad is young, thin, and beautiful, and yet she feels anxious about being seen in a bathing suit. How are we mortals supposed to feel?

Virginia Slims cigarettes initially were marketed as “slimmer, longer, not like those fat cigarettes men smoke.” In addition to the promise of weight control, this language is quite clearly sexual. Overcoming “penis envy” certainly seems to be part of the Virginia Slims message. In one ad, the model tauntingly says, “He said, ‘A slims that’s even longer?’ I said, Jealous?” This even brought protests from advertisers. Advertising Age published a letter from a copywriter that said, “Here’s my vote for the new year’s first bad ad. Get a load of the expression on the model’s face and the little bit of subtle dialog, then tell me that Philip Morris hasn’t hit a new low in the battle of the sexes.”

As psychologist Karen Horney pointed out in her critique of Freudian theory in the 1920s, it wasn’t the actual penis that women envied and wanted, it was the power that the penis represents. Virginia Slims tells women that by bringing this phallic object, even longer than a man’s, to our lips, we can take on some of men’s power. We won’t even need men any more. We’ll be independent, self-sufficient.

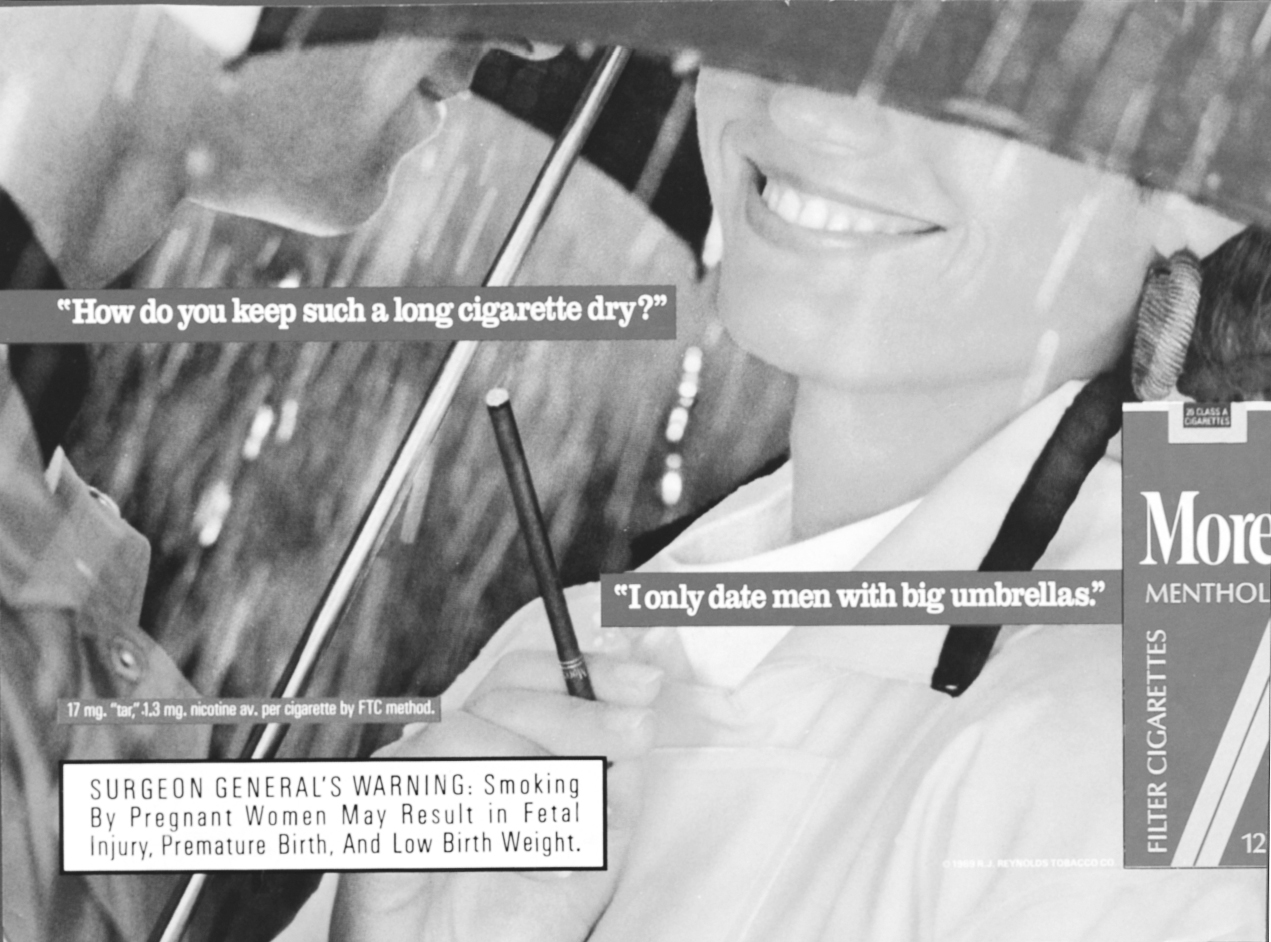

Of course, there is nothing new about using sexual innuendo to sell cigarettes. “It’s what’s up front that counts” was once the slogan for Tareyton. “I don’t judge my cigarette by its length,” announced a stern-faced man in a Winston ad from the 1970s. “Who says length doesn’t matter?” confides one woman to another in a recent ad for Eve Lights.

In the late 1980s More had a campaign featuring a man and a woman in extreme closeup flirtatiously discussing her long cigarette. “Why such a long cigarette?” he asks her and she replies, “I like to stretch things out.” “Is it hard to smoke a cigarette that long,” he asks in another ad, and she replies, “Only if you’re in a hurry.” In the most blatant of them all, he says, “How do you keep such a long cigarette dry?” and she responds, “I only date men with big umbrellas.”

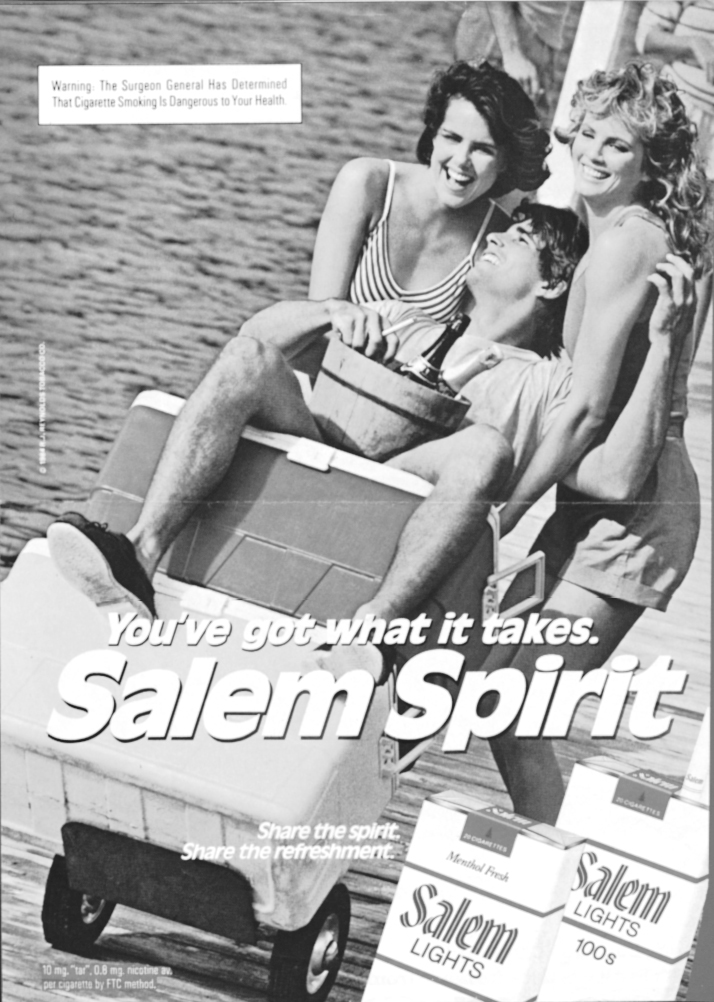

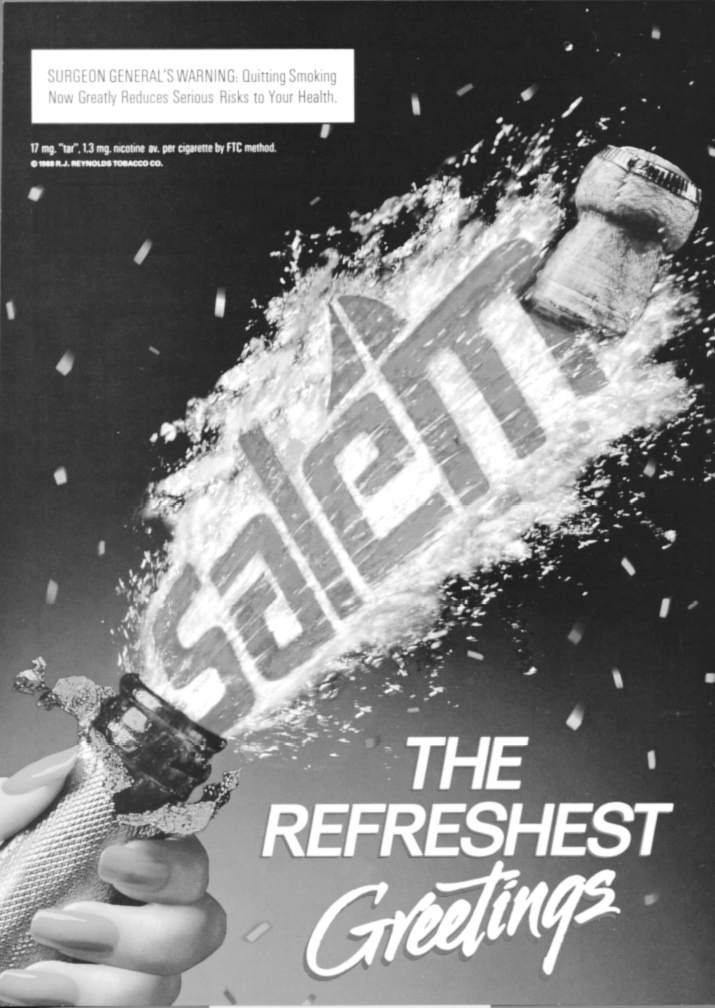

Phallic imagery as well as sexual innuendo is often used in cigarette ads. A Salem ad features a man being pushed on a cart by two women, with the slogan “You’ve got what it takes.” Nestled between the man’s legs are two bottles, each one pointing at one of the women. More recently, another Salem ad features a woman’s hand caressing a champagne bottle as it pops its cork.

One doesn’t have to search for exotic subliminal images. Joe Camel is perhaps the most blatant phallic symbol in the history of advertising. I sometimes refer to him in my lectures as the rare Australian Dick-Faced Camel. Richard Pollay, curator of the Advertising Archives at the University of British Columbia, has also commented on Joe’s extraordinarily well-hung nose and refers to him as Genital Joe.

Why would R. J. Reynolds use such an image? Because it is offering power to children, especially to boys. The ads contain all kinds of icons of power, such as motorcycles, ships, airplanes, usually thrusting into the air. Everything is erect! Joe’s phallic face underscores the message: smoke this brand of cigarettes and you will be a man, you will be powerful. Perhaps young girls get the message that smoking will give them some of the power held by men, the same message Virginia Slims is giving them.

Or perhaps girls and young women are amused by Joe Camel. Elizabeth Hirschman, a marketing professor at Rutgers University, wrote:

How many times have we—in our female-chauvinist, male-degrading minds—thought that a particular man, or occasionally even men in general, were indeed pricks (or in Yiddish terms: schmucks with ears). Here, in full-color spreads pasted across billboards, double-trucking through magazines and newspapers, peering down from supermarket cigarette counters, is proof-positive that we were right! Thus, although young men may think it is arousing to have their private parts on public display, dressed up in various costumes, women see these same images as poetic justice: men are dicks!

Countless cigarette ads feature men with fishing poles between their legs, jackhammers, tree trunks, telephone poles. Newport had an entire campaign based on phallic images so blatant that they were often hilarious. A man and woman hug with some gigantic balloons between them. A woman feeds a man a huge icicle or marshmallows from a long stick . . . or squirts wine into his mouth from a winebag. A woman jumps over an ejaculating fire hydrant. This campaign would appeal to both men and women. Both are promised exciting sex and phallic power via the cigarette. It is quite possible that these ads are also playing on men’s fears of being inadequate, of not measuring up. In this case, their effect on men would be similar to the effect of the Virginia Slims ads on women: They would create anxiety and offer the cigarette to alleviate it.

The subliminal phallic images are silly, sometimes hilarious. But they make clear the intent of the advertisers, which is to addict people to a lethal product in whatever way necessary, including promising power to the most powerless people in our society—children, especially children at risk. And many young people, influenced by these images whether they know it or not, fall for this promise. According to a Philip Morris document, “Smoking a cigarette for the beginner is a symbolic act. . . . I am no longer my mother’s child, I’m tough, I am an adventurer, I’m not square.’ . . . As the force from the psychological symbolism subsides, the pharmacological effect takes over to sustain the habit.” In plain language, the child becomes addicted.

The irony, of course, is that cigarettes, like alcohol, are linked with impotence. Indeed, smokers are 50 percent more likely to suffer from impotence than nonsmokers. A 1959 tobacco industry study concluded that it is “not strength but weakness of the masculine component” that is “more frequent in the heavier smokers.” Thus, it is very important for advertisers to make smokers feel like virile cowboys. In addition, smoking itself is increasingly linked with symbolic impotence in our society, as the powerful people quit and our most vulnerable children become addicted. No wonder it is more important than ever for the tobacco industry to promise potency to these powerless children and addicted adults. But what a travesty this is—not only does the product not deliver the promised potency, it actually depletes it, in ways ranging from literal impotence to social liability and ostracism to illness and death.

In addition to offering potency on an unconscious level, ads also very directly offer cigarettes to young people as a way to be more powerful. A major theme in cigarette advertising is that smoking is a brave and gutsy thing to do. Many ads feature risky activities, such as hang-gliding, auto-racing, and parasailing. Be a daredevil, be a rebel, the ads seem to say. “Some people still surf without a net,” says an ad for Winston featuring a surfboard in a convertible. Many young smokers are rebellious and are also likely to be sensation-seekers. It is no coincidence that tobacco companies are the leading sponsors of events that appeal to risk-taking and rebellious teenagers, such as motorcycle, dirt bike, and hot rod races, rodeos, and ballooning.

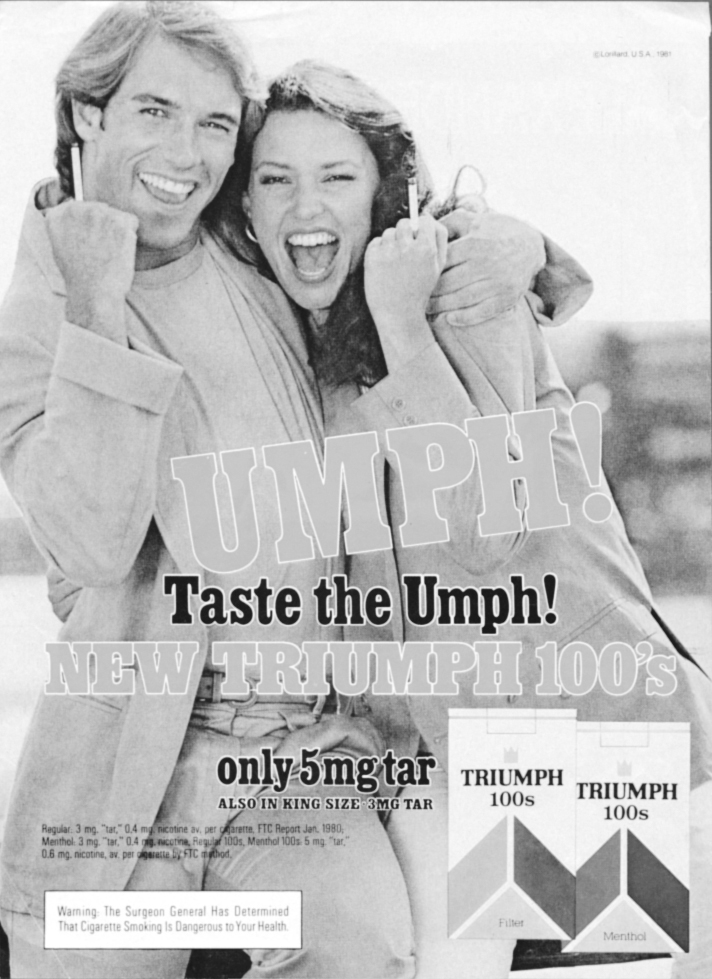

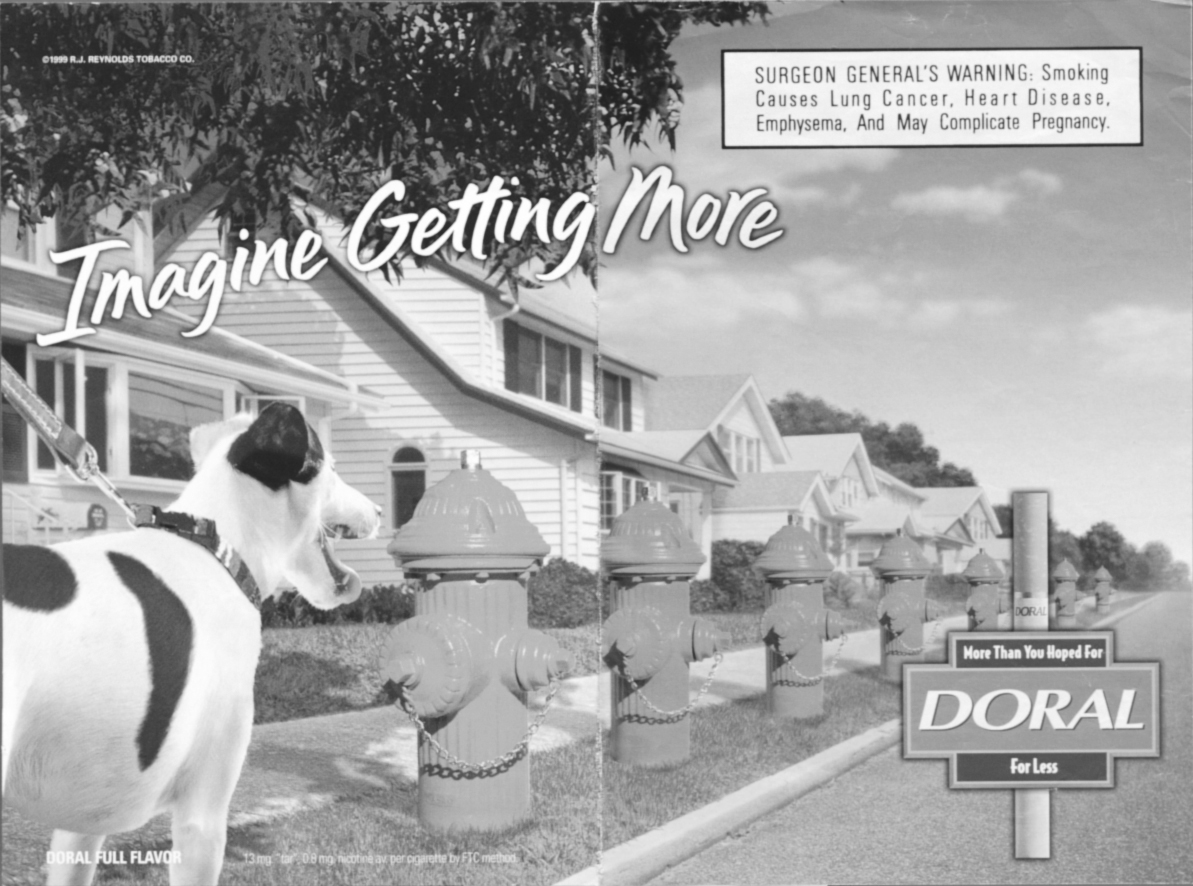

The tobacco industry also appeals to rebellious teenagers in other ways. They promote the cigarette itself as an emblem of independence and nonconformity. The smoker is portrayed as the man (or woman) who dares to defy public opinion, to stand on his or her own. “No compromise” declares one campaign for Winston. “Buck the system,” says an ad for low-priced Buck cigarettes. Triumph had a whole campaign in which Triumph smokers symbolically gave the world the finger. More recently, Doral ran an ad in TV Guide, a magazine seen by millions of young people, which features a dog staring at a row of fire hydrants. “Imagine getting more” is the tagline, but “Piss on the world” might be more accurate.

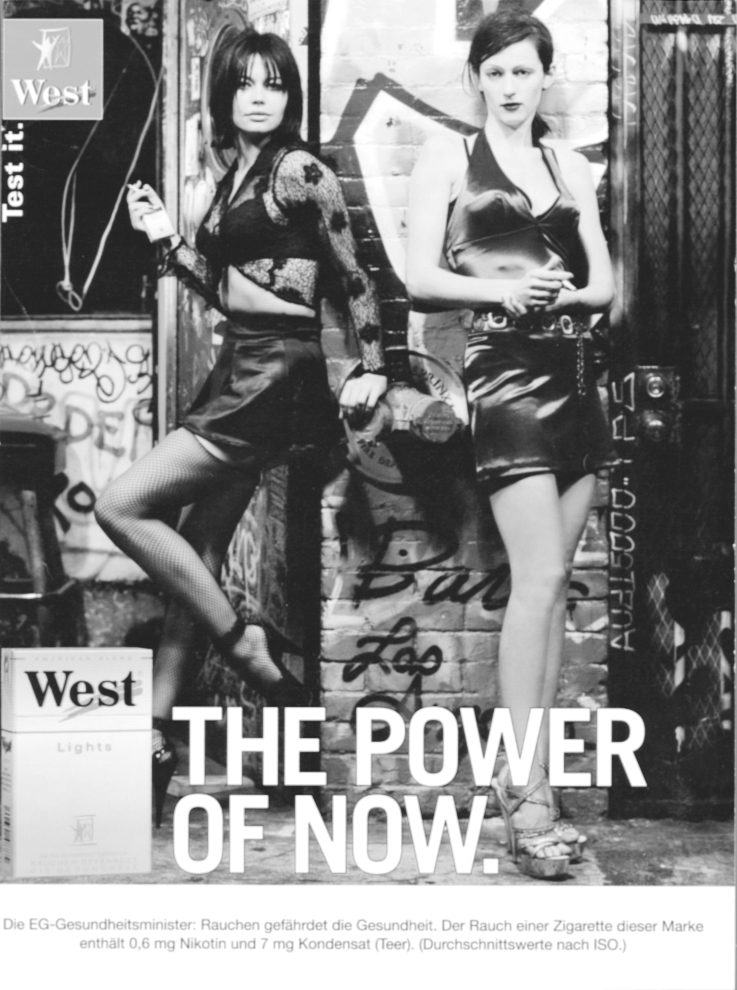

Teenage girls, who identify smoking with independence and rebellion, are especially vulnerable to this pitch. Young men in cigarette ads are far more likely than young women to be physically daring, to be engaged in a dangerous sport or activity. Young women are pictured as daring when they act tough or defy conventional feminine stereotypes or wear outrageous clothing. “Go wild,” says a Virginia Slims ad. And just how are young women supposed to demonstrate this wildness? “Call for our new catalog,” says the ad. Capri had a campaign in the early 1990s featuring a series of young women flaunting their cigarettes while the headlines said “A taste for the UNconventional,” “A taste for the outspoken,” “A taste for the daring,” and so forth.

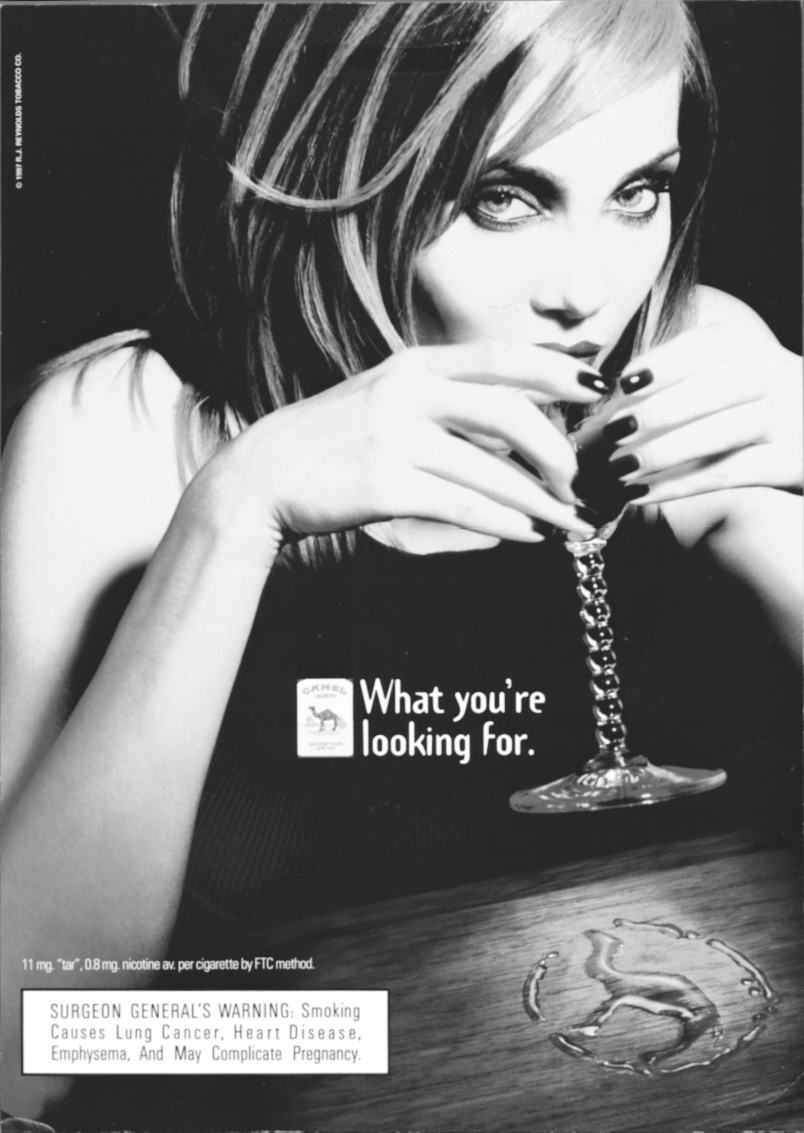

Young women are also considered daring and wild when they are overtly sexual. “Light my Lucky,” a series of very young, very defiant-looking women told us in the mid-1980s. “The power of now,” says a German ad, for a brand of ciga-

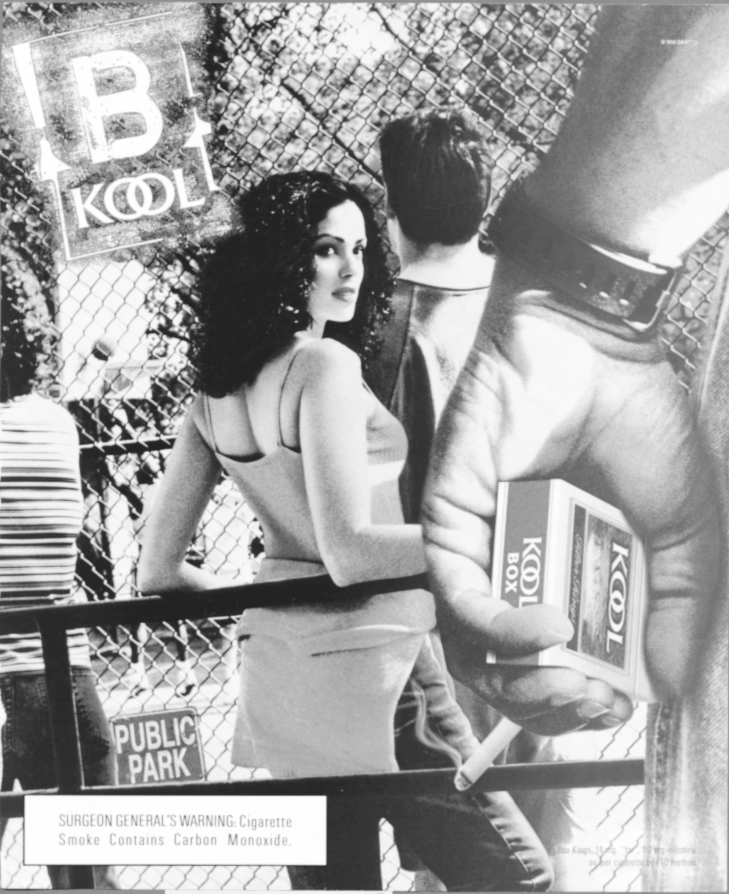

“What you’re looking for,” is the tagline for a Camel campaign in the late 1990s. Some of the ads picture very seductive young women. A concurrent Kool campaign running in magazines and on billboards features various sexy young women whose attention is drawn away from the oblivious men with them to another man who is holding a lit cigarette (we see only his hand). “B Kool” is the tagline. These campaigns appeal to both boys and girls, with their promise of seduction and sexual adventure.

In a Winston ad, a young woman looks defiantly at the reader and declares, “My buns might not be steel, but my butt’s all tobacco.” Here she seems to be a tough cookie who is bravely defying the cultural demand for perfection in women’s bodies and yet she is rebelling in a stereotypical “female” way—by harming herself. This ad is reminiscent of the Michelob ad that urges young women to ignore the demands of the fashion magazines for physical perfection and to “relax and enjoy your beer.”

Another ad in the Winston campaign features an attractive young woman pushing her way into the men’s room. “My patience is gone,” she explains, “and so are the additives in my smokes.” She, and all the other “daring” young women, are, of course, basically tithing to the tobacco men, who profit mightily from their “rebellion.”

Unfortunately, the negative focus on smoking in recent years only increases its allure for rebellious young people. They are attracted to an activity that is both hazardous to health and socially unacceptable. It is difficult to dissuade people by emphasizing the dangerousness of a product, when that very danger is a large part of the appeal. Thus smokers in the United States today are more likely than ever to be especially rebellious and even “deviant.”

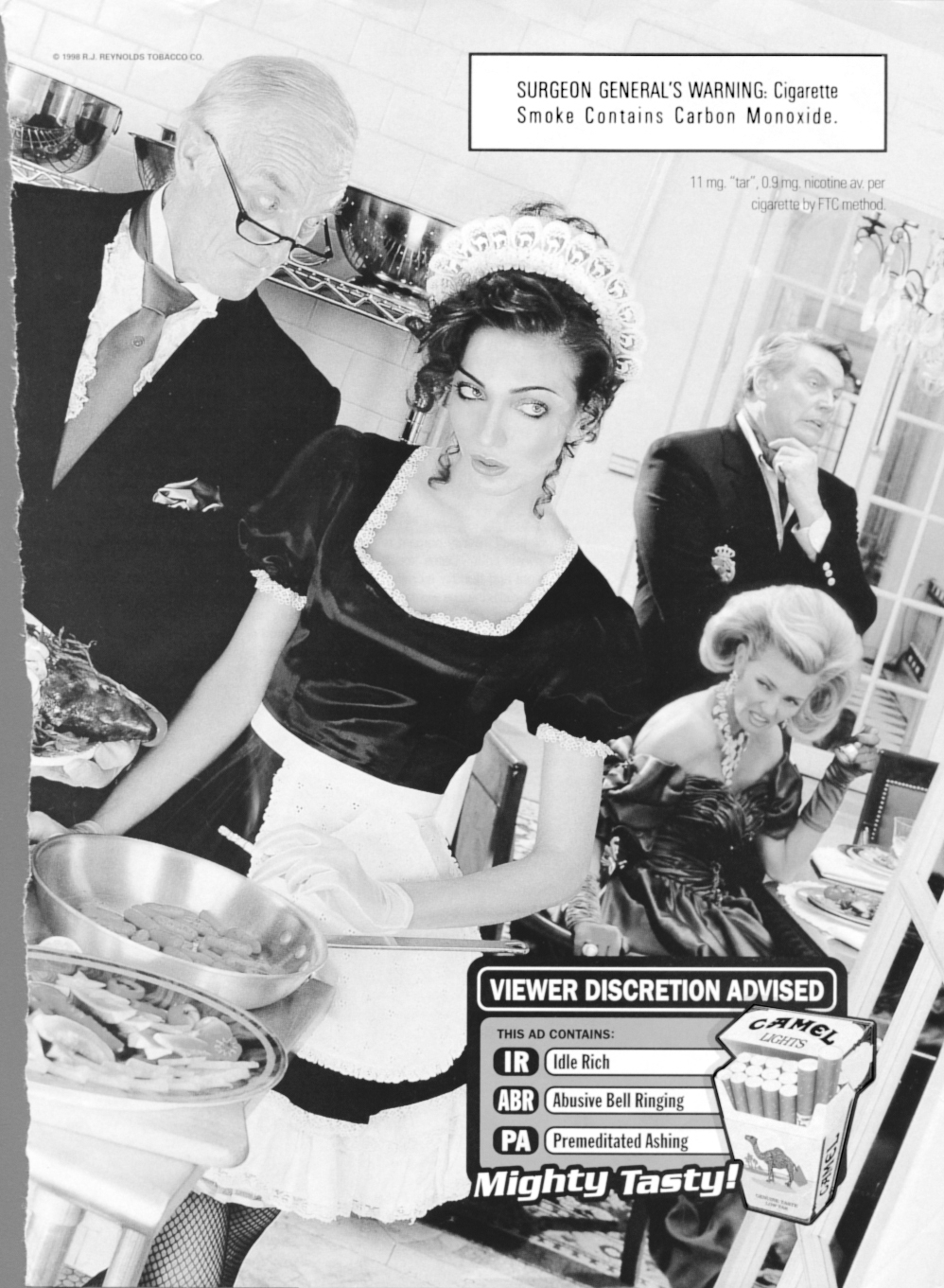

The tobacco industry often attempts to glamorize this deviance. The Camel campaign that followed the demise of Joe Camel features scenes of outrageous behavior, such as a maid flicking ashes over an abusive rich woman’s dinner and phony “warnings” under the heading “Viewer Discretion Advised,” such as IR for Idle Rich and PA for Premeditated Ashing. These ads are clearly meant to satirize the concern about Joe Camel and about the hazards of smoking in general and to encourage people to take the whole issue more lightly. Indeed the campaign itself gives the finger to antismoking activists by clearly appealing to kids every bit as effectively and cynically as did Joe Camel.

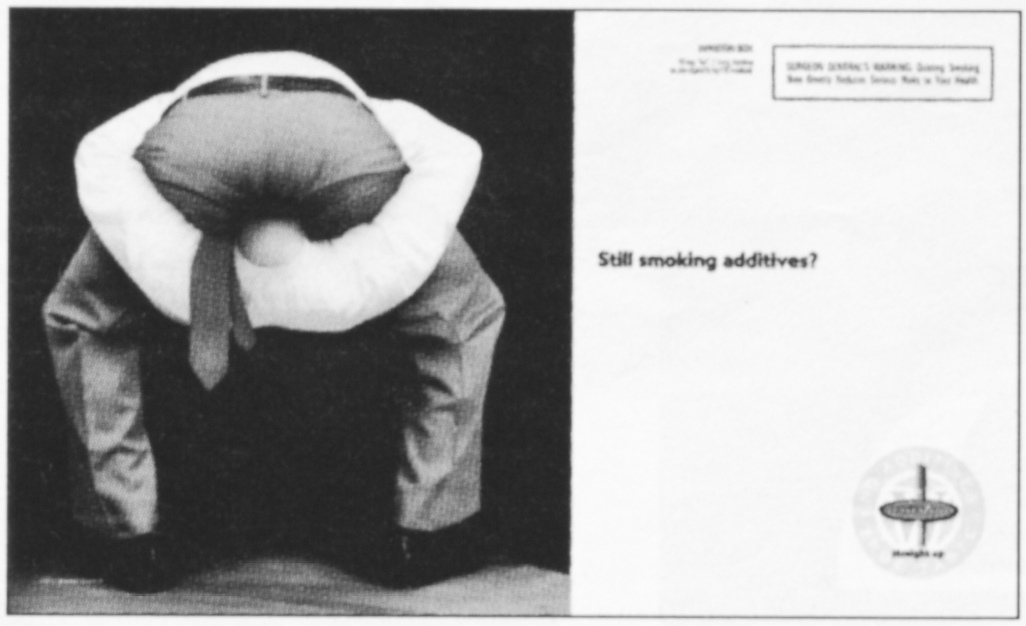

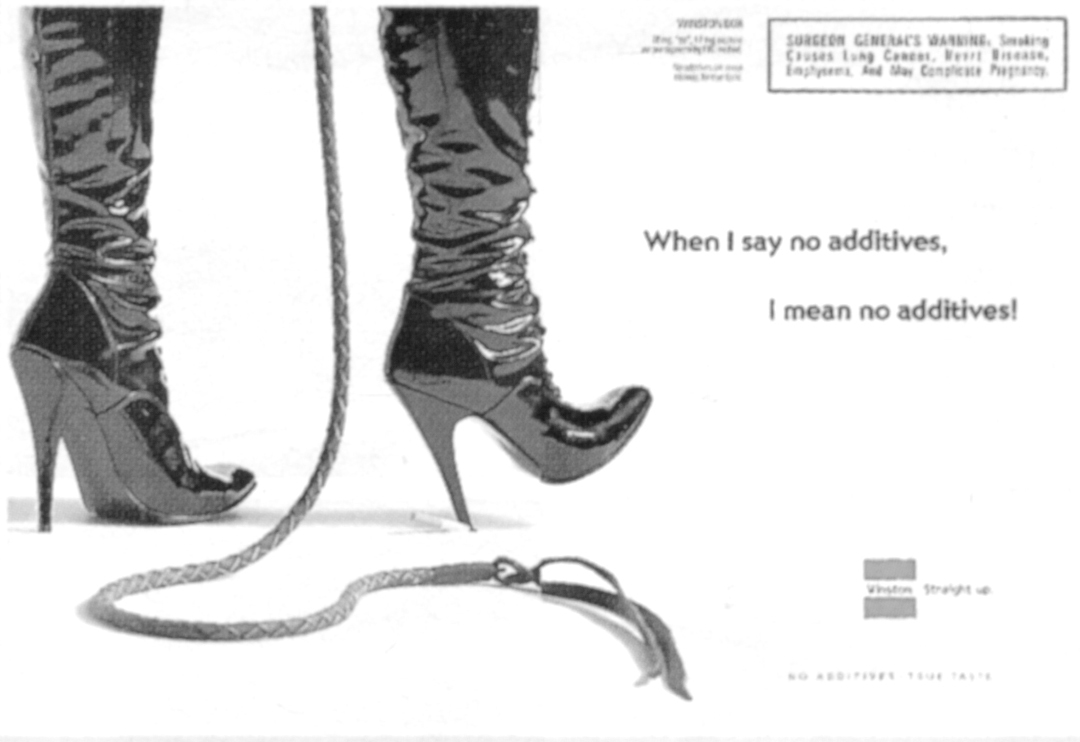

Winston goes several steps further in its campaign of the late 1990s. “Finally a butt worth kissing,” proclaims one of the ads in this campaign, not only in magazines but on billboards for all to see. The most amazing example is an ad that ran in youth-oriented magazines such as Rolling Stone that features a man with his head literally up his butt. “Still smoking additives?” says the irrelevant copy. What is the point of this campaign? It’s meant to appeal to young smokers who relish the idea of being deviant, rebellious, even offensive. According to media critic Mark Crispin Miller, cigarette ads in general these days “offer none of the idyllic and escapist scenes that filled the advertising prior to the ‘80s. Instead, the pitch is nasty and divisive, appealing to the worst impulses of those who smoke or who might start to smoke.” He argues that cigarette ads often portray the smoker as a threatening, aggressive figure whose power derives from the cruel domination of the other. Nowhere is this more evident than in the Winston ad featuring a dominatrix with a whip saying, “When I say no additives, I mean no additives.”

A long-running Benson & Hedges ad glamorizes deviance in a much less heavy-handed way by poking fun at efforts to restrict smoking in public. “Have you noticed the welcome mat is hardly ever out for smokers?” asks an ad featuring attractive young people smoking together on a rooftop. “For a great smoke, make yourself at home.”

Sometimes the ads picture smokers in social situations, other times at work, such as the ad featuring people sitting at desks outside on office window ledges and the copy, “Have you noticed finding a place to smoke is the hardest part of your job? For a great smoke, put in for a window office.” Another ad in the campaign features young people riding on top of a train. “These days commuters can’t climb aboard with a cigarette. For Benson & Hedges, travel the scenic route.” Whatever the case the smokers are always very attractive and seem to be having lots of fun.

The link with freedom is made most explicit in the Benson & Hedges ad featuring smokers sitting on top of the Statue of Liberty. “Ever wonder why she’s holding a light?” asks the copy. “For a great smoke, take a few liberties.”

The tobacco industry is attempting to get even more mileage from this image by portraying public health advocates as antismoking fanatics who want to tell everybody else what to do (what R.J. Reynolds refers to as the “Lifestyle Police”) and setting us against the courageous, independent, free-thinking smoker. The billions of dollars the industry has poured into advertising campaigns equating smoking with freedom have had an extra dividend: Critics of smoking are seen as enemies of freedom. For several years the tobacco industry has been running a very expensive public-relations campaign that equates smoking with freedom and the criticism of smoking with totalitarianism.

Perhaps the most outrageous example of this campaign was Philip Morris’s use of the Bill of Rights to promote smoking. They enlisted politicians, actors, and even a former American POW in their ads. The POW, Everett Alvarez, says, “You’ll never know how sweet freedom can be unless you’ve lost it for eight and a half years.” Thus Philip Morris is associated with freedom and the anti-tobacco-industry forces are associated with America’s enemies, such as the North Vietnamese.

R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company used the same ploy in a full-page newspaper ad featuring photos of the Berlin Wall collapsing, Russia approving the new constitution, and the African National Congress celebrating victory in South Africa juxtaposed with a photo of some people forced to smoke outside their office building and the ludicrous headline, “Where exactly is the land of the free?” Once again the people fighting for public health are identified with the enemy—with communists and the creators of apartheid. These ads also undermine the government. Indeed the tobacco industry has played a major role in the burgeoning hostility of Americans to their own government. Although it is not the whole story, of course, it is no coincidence that Bill Clinton is the first president in U.S. history who has taken on the tobacco industry and that Ken Starr is a tobacco industry lawyer.

Consider a full-page ad run in virtually every newspaper in the country that featured a solemn woman saying, “The smell of cigarette smoke annoys me, but not as much as the government telling me what to do.” In ad after ad like this, the industry tries to turn a public health issue into a political issue. Imagine this approach about some other public health issue, such as the immunization program for children or alcohol-impaired driving. Imagine a woman in an ad saying, “The death of small children annoys me, but . . .” Or “Drunk drivers annoy me, but . . .” The use of the word “annoys” trivializes the whole issue. Cigarette smoke is not an annoyance—it is a proven killer, of nonsmokers as well as smokers.

The alcohol industry also often takes an antigovernment stance, as in an Absolute ad headlined “Absolut DC,” which features the familiar bottle all wrapped up in red tape. It is very much to the alcohol and tobacco industries’ advantage to have a noninterventionist government and a cynical and apathetic citizenry. Both industries, in their advertising, not only ridicule the government, they promote apathy. “Scientists predict global warming,” says a beer ad featuring a six-pack. “Miller says no problem.” Don’t worry about the destruction of the environment . . . just have another beer or six.

“Make the world a brighter place,” says a Virginia Slims ad featuring three women sitting on a snowbank, but the ad suggests no way to do this other than via the glow of one’s cigarette. Meantime, Philip Morris’s (maker of Virginia Slims) way to make the world a brighter place is to addict more women and girls all over the globe. Its international sales have quadrupled in the past decade. Worldwide today, 47 percent of men smoke compared to only 12 percent of women. In developing countries, between 2 and 10 percent of women smoke compared with 25 to 30 percent in developed countries. Two out of the top three global tobacco companies are American, and they are aggressively targeting women and girls in developing countries with slick advertising promising emancipation, power, and slimness with every puff. They sponsor tours by female pop stars, fashion shows, and other promotions. One year after the entry of American tobacco companies into Korea, smoking rates among female teenagers increased from less than 2 percent to nearly 9 percent. “Camel Planet,” says an ad in a Polish youth-oriented magazine, which reads, “The Earth is ours. You have no alternative. Either you come to us or we come to you.” Mark Palmer, the U.S. ambassador to Hungary, said, “[The United States and its allies] worked for 45 years to get the communists out. And when we did, the Marlboro Man rode into town to claim the victory.”

Is it far-fetched and “paranoid” to suspect such cynical and deliberate manipulation? I am not at all suggesting that women are offered cigarettes in the way that Native Americans were offered alcohol or the Chinese opium, as a conscious attempt on the part of those in power to demoralize and destroy them. However, there are some similarities in the results. For all the talk about freedom and liberation, the truth is that addiction of any kind makes women more passive and far less likely to rebel in any meaningful way. When people are drunk or stoned or high, they don’t usually have the energy or the focus to make serious changes in their situation as individuals, let alone as a group. As Barbara Gordon said in I’m Dancing as Fast as I Can, the harrowing account of her Valium addiction, “As long as I took the pills, I had been incapable of feeling the anger necessary to make changes in my life.”

Addiction hinders a woman’s search for equality and power in many ways, not least by defusing the anger and frustration necessary to fuel it. As one former smoker in the New York roundtable discussions said, “Smoking was a release. When things bothered me, I would have a cigarette to avoid dealing with them. Now I don’t have the release, so I tend to deal with problems head on.” Certainly this is far better than the conclusion drawn by the young woman who used cigarettes to control her anger in a Teen article: “My problems are still there, but the tension is gone.” As Sue Delaney said in her book Women Smokers Can Quit: A Different Approach, “Sometimes we smoke when it would be better to speak. Sometimes we smoke when it would be better to act.”

Girls and women are encouraged to use cigarettes and alcohol to cope with anger and depression and to repress their authentic rebelliousness, all the while deluding themselves that they are being genuinely defiant. The girls and women most likely to smoke, the rebels, the risk-takers, the “bad girls,” are the very ones most likely to change the system if they had direct access to their energy and their rage. If they were to stop smoking, not only would many lives be saved, but we might also gain access to some of the collective energy presently stifled and defused by cigarettes. This in turn could bring about true liberation for women—and ultimately greater freedom for men too—rather than the illusory liberation offered in the cigarette ads. As Jill Nelson, writing about the rage of African-American women, says, “Mostly, this happens individually, when one woman has reached her end, has had enough of violence, or dishonesty, or being demonized, or being invisible, and breaks out, goes off. It is a powerful thing when this happens. Imagine how much power we’d have if we could figure out how to do this collectively”