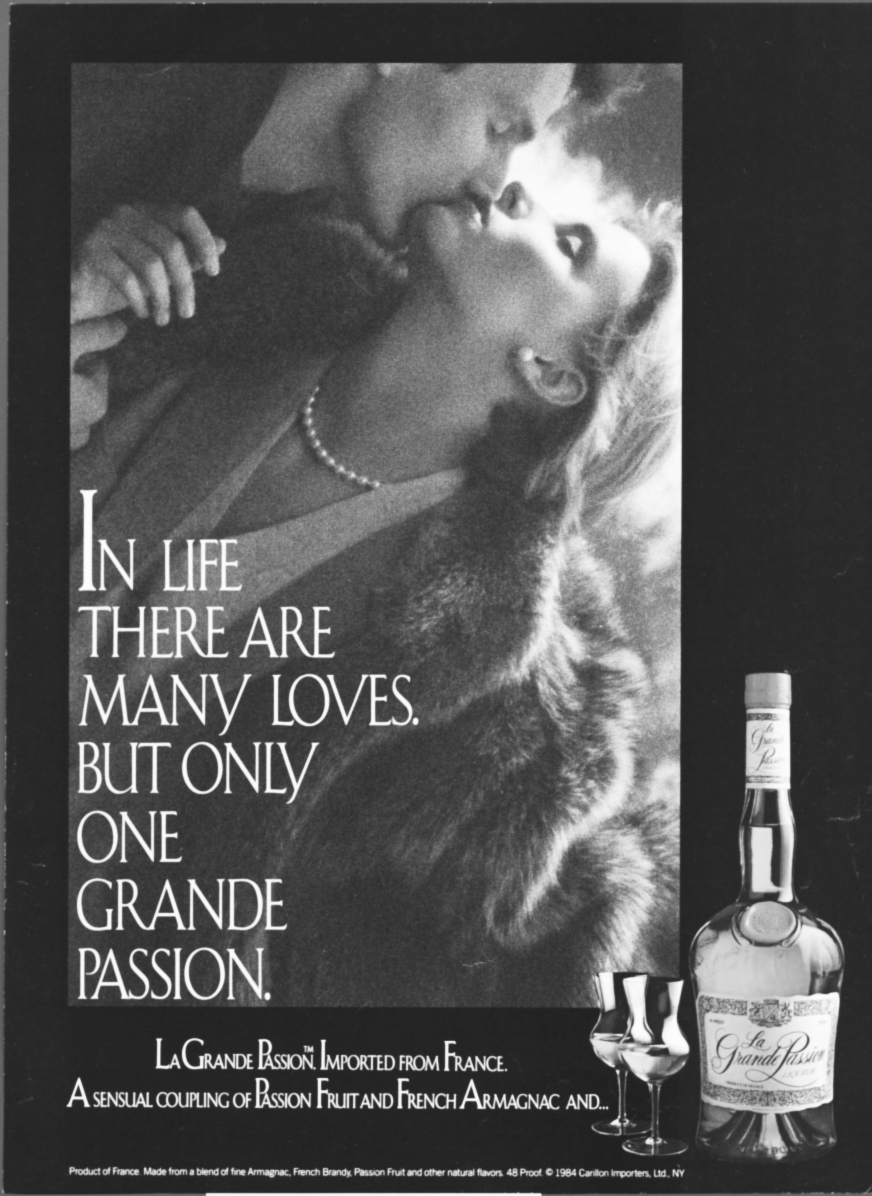

“IN LIFE THERE ARE MANY LOVES, BUT ONLY ONE GRANDE PASSION”

Addiction as a Relationship

![]()

“DO YOU LOVE BEER?” A SMOOTH MALE VOICE ASKS, WHILE THE CAMERA lovingly caresses a foaming glass of beer. “If you could have only one thing in your refrigerator, what would it be? . . . How many different languages can you order beer in? . . . Have you ever spent twenty minutes in the beer aisle? . . . Do you love beer?” This is one in a series of commercials for Sam Adams beer that ask different versions of the same question.

A very powerful 1997 commercial gives the alcoholic’s answer to this question. The opening shot is of beer pouring from a tap. A man in his bedroom, looking haggard and anxious, hung over, looks into the mirror and sees an image of Guinness. On the soundtrack we hear the old Platters hit, “My prayer is to linger with you, at the end of the day, in a dream that’s divine.”

The man hears the ocean roar, looks up at a skylight, and sees the image of Guinness again. He looks at an aquarium and sees the image again. He goes outdoors and sees the image in a puddle. He is in a bar, everything in slow motion, welcomed warmly by friends. A woman looks at him very intensely, but he raises his glass of Guinness, which completely obscures her face. He licks his lips and focuses entirely on the drink. This commercial completely captures the alcoholic’s intense focus on his drug—the man sees the bottle everywhere, his drink obliterates the face of the woman looking at him. She is of no importance—only the bottle is real to him.

Advertisers spend an enormous amount of money on psychological research. As the chairman of one advertising agency says, “If you want to get into people’s wallets, first you have to get into their lives.” As a result, they understand addiction very well. Soon after I began my study of alcohol advertising, I realized with horror that alcohol advertisers understand alcoholism perhaps better than any other group in the country. And they use this knowledge to keep people in denial.

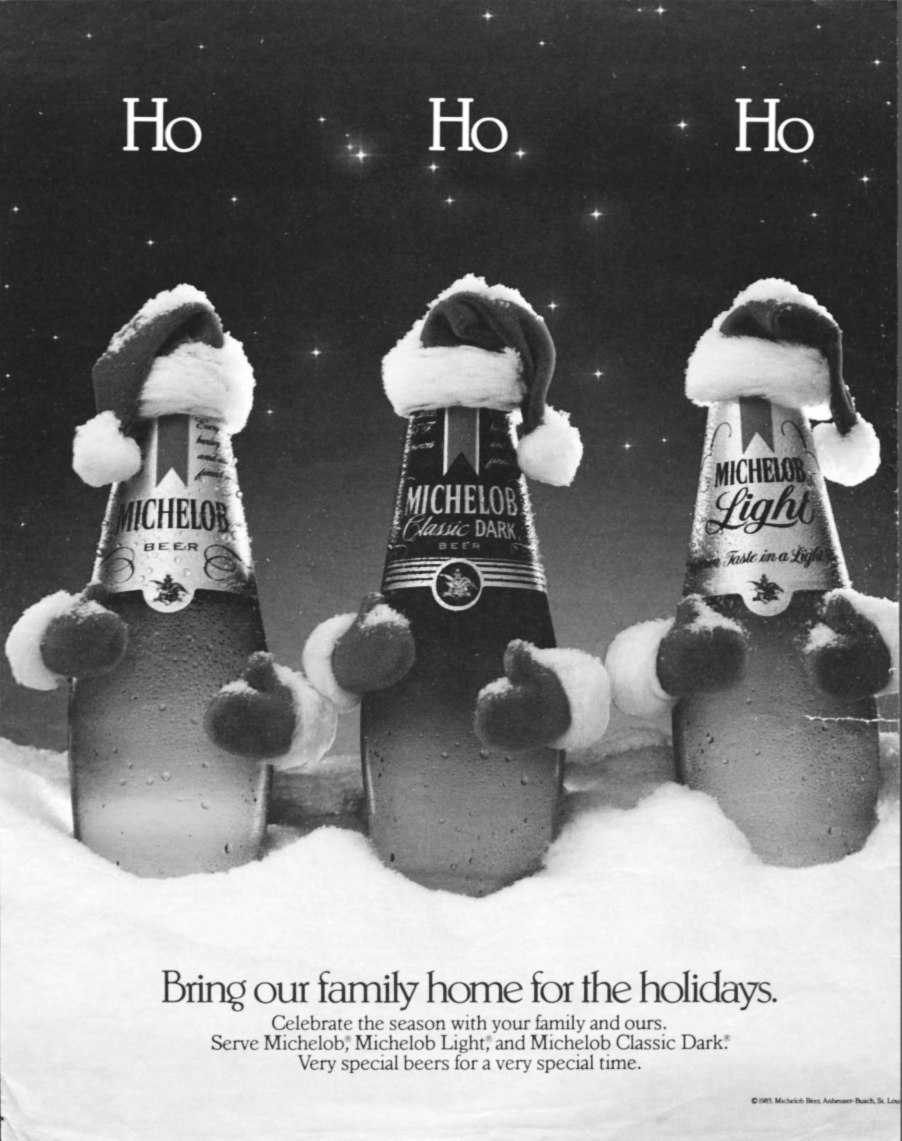

The addict’s powerful belief that the substance is a friend or lover is constantly reinforced by advertising. In alcohol ads, the bottle itself is sometimes portrayed as the friend or family member. “Bring our family home for the holidays,” says a Michelob ad, in which the beer bottles are dressed up as Santa Claus. Another describes a bottle of vodka as “The perfect summer guest.” A sign outside a bar at Chicago’s O’Hare Airport says, “Why wait at the gate? Your Bud’s at the bar.” Bud Light takes this theme one step further in an ad featuring two women engrossed in conversation over bottles of beer, with the copy, “Is the best thing about sharing a secret who you share it with or what you share it over?”

Dogs often appear in alcohol ads as a symbol of “man’s best friend.” A gorgeous Irish setter is pictured in a Johnnie Walker Red ad above the headline, “It’s funny how often the comforts of home include Red.” A cognac ad, featuring a bloodhound sleeping by the fire, declares “You’ve been working like one for years, it’s time you threw yourself a bone,” and a Saint Bernard with a bottle of Chivas Regal around his neck appears above the copy, “It’s enough to make you want to get lost.” A beer called “Red Dog” uses a picture of a bulldog and the slogan “Be your own dog.” More recently, a Miller Lite commercial shows people playing with a puppy and announcing that the beer is “Man’s Other Best Friend.” The message is clear: Alcohol is loyal and steadfast, just like your dog. Alcohol will never let you down. Alcohol is always there when you need it.

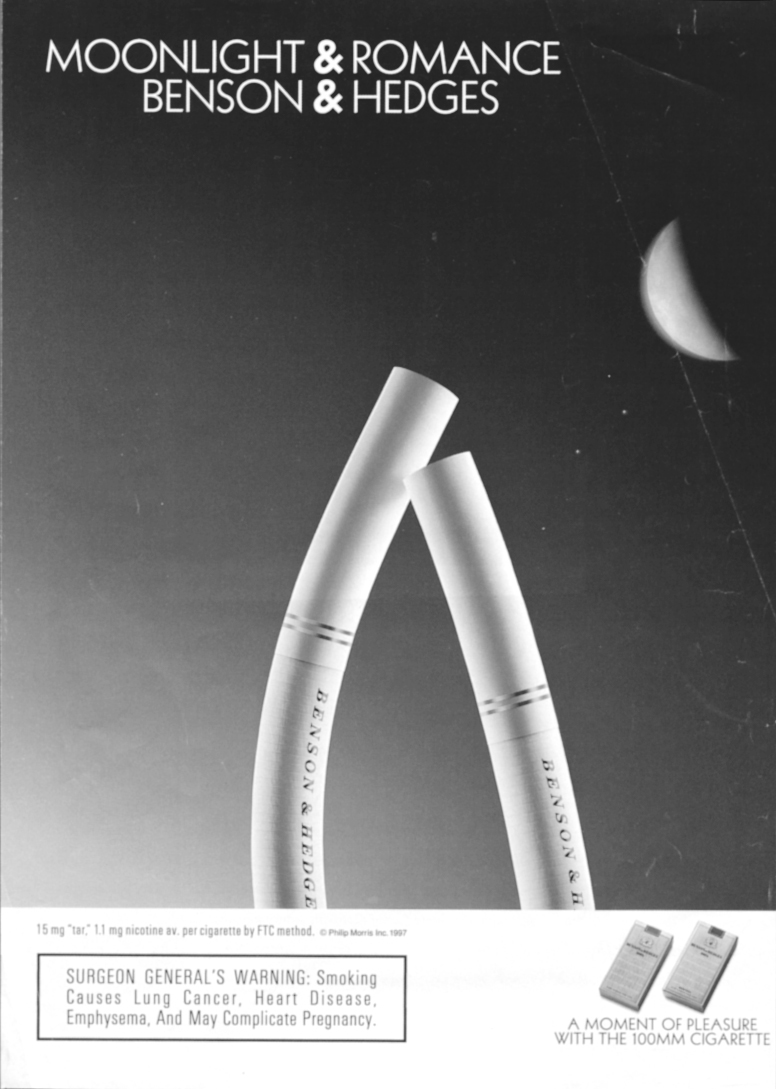

Cigarettes are also often portrayed as friends, companions. Anthropomorphic cigarettes star in a campaign for Benson & Hedges. “Sitting and talking” features two cigarettes on a porch swing. This pitch is especially effective with women because we are socialized to see ourselves in a relational context. Many cigarette ads feature women together, often just talking, with the cigarette as the symbolic bond between them. Sometimes there is deliberate ambiguity about whether the most important relationship is with the friend or the cigarette, as in a Virginia Slims ad featuring two women together with the copy, “The best part about taking a break is who you take it with.”

Cigarettes are also used by women, and sometimes by men as well, to facilitate relationships in other ways. They can defuse tense situations or hide anxiety. There is a whole lexicon of smoking as a facilitator for sexual activity, ranging from the man handing a lit cigarette to a woman to her blowing the smoke suggestively in his direction to the two of them sharing a cigarette in the bedroom following their lovemaking.

Even more than a friendship, addiction is a romance—a romance that inevitably goes sour, but that is amazingly intense. As Lou Reed sang in a song called “Heroin,” “It’s my life and it’s my wife.” “Your Basic Romance” says a cigarette ad, while another, headlined “Moonlight and romance,” features two cigarettes touching by the light of the moon. And an ad for More features the cigarette leaning against a personal ad that says, “Wanted. Tall dark stranger for long lasting relationship. Good looks, great taste a must. Signed, Eagerly Seeking Smoking Satisfaction.” The long brown cigarette is, of course, the “tall dark stranger.” And the tobacco industry certainly hopes that the relationship will be long-lasting.

A liqueur ad features a loving couple and the headline “The romance never goes out of some marriages.” But it turns out the true marriage is of Benedictine and Brandy, the ingredients of the liqueur. “The result is what every marriage should be—unvarying delight. That’s why when there is romance in your soul, there should be B and B in your glass.” Alcoholics are far more likely than nonalcoholics to be divorced, but maybe that’s because they weren’t drinking B and B. And smokers are 53 percent more likely to have been divorced than nonsmokers. An important part of the denial so necessary to maintain alcoholism or any other addiction is the belief that one’s alcohol use isn’t affecting one’s relationships. The truth, of course, is that addictions shatter relationships. Ads like the one for B and B help support the denial and go one step further by telling us that alcohol is, in fact, an enhancement to relationships.

“In life there are many loves. But only one Grande Passion,” says an ad featuring a couple in a passionate embrace. Is the passion enhanced by the liqueur or is the passion for the liqueur? For many years I described my drinking as a love affair, joking that Jack Daniels was my most constant lover. When I said this at my lectures or my support group meetings, there were always nods of recognition. Caroline Knapp used this idea as the central metaphor of her memoir about her recovery from alcoholism, Drinking: A Love Story, which begins, “It happened this way: I fell in love and then, because the love was ruining everything I cared about, I had to fall out.” And Margaret Bullitt-Jonas titled her book about recovering from an eating disorder Holy Hunger: A Memoir of Desire.

I can remember loving the names of drinks, from sloe gin fizzes to Manhattans. I loved the look of bottles glowing like jewels in the mirror of a bar—ruby, amber, emerald, topaz. I loved the paraphernalia of drinking—the cherries and olives, the translucent slices of lemon, the salt on the rim of the glass, the frost on the shotglass waiting for the syrupy Stolichnaya straight from the freezer.

Even now, over twenty years since my last drink, if I suddenly catch a glimpse of Jack Daniels on a shelf or in someone’s shopping cart, it’s a bit like running into an old lover—a lover who was dangerous and destructive, but who completely captured my heart. “You Don’t Own Me” was my theme song in high school, a reflection of how frightened I was by intimate relationships, but the truth is that, for many crucial years thereafter, alcohol owned me, heart and soul.

I loved the way alcohol made me feel, the coziness and warmth, the lifting of care. I remember how the first sip of alcohol felt so warm, every time. The glowing feeling in my solar plexus grew more intense as I got high. I felt embraced by alcohol, felt safely enclosed in a little cave of amber light. When I was with another person, I often mistook that little cave for intimacy. The rest of the world went away.

I’ve been struck since by how many ads re-create the glow, the cave of amber light. There is often a golden halo around the bottle or around the drink itself. A cognac ad features two men, perhaps a father and son, embracing. The copy says, “If you’ve ever come in from the cold, you already know the feeling of Cognac Hennessy.” The two men are in black and white, but the label and the glasses of cognac are a rich, deep amber. The alcohol ads not only promise intimacy, they promise spectacular intimacy, a closeness one has never experienced before. The men in the cognac ad were perhaps estranged, they were out in the cold. Now they are inside the circle of warmth, and alcohol has brought them there. For many years I believed, as most alcoholics do, that only alcohol could take me into that circle. Without it, I was outside, alone. It frightens me still to realize how deeply alcohol advertisers understand the precise nature of the addiction and how deliberately and destructively they use their knowledge.

It is one thing when advertisers exploit people’s longing for relationship and connection to sell us shoes or shampoo or even cars. It is quite another when they exploit it to sell us an addictive product. As we saw earlier, some of the ways that products seem to meet Jean Baker Miller’s terms for a growth-enhancing connection—increased sense of zest, empowerment to act, greater clarity and self-knowledge, a greater sense of self-worth, and a desire for more connection—are funny and clever and seemingly harmless. It’s a great deal more sinister when the products are potentially addictive. We’re not likely really to believe that shampoo is going to improve our sex lives, for example, but we might well believe that champagne will.

It is especially sinister for women because so much of our drinking is connected with our relationships with other people. This begins in childhood when problems in relationships, such as early separation from a parent or sexual abuse, predict a greater likelihood of alcoholism. Later in life a loss or impairment of a close relationship, such as divorce or having a partner with whom we feel unable to talk, often influences women drinkers to drink more heavily. And many women drink in an attempt to facilitate relationships, to reduce sexual inhibition, and to be able to speak more openly, especially when angry or upset. Perhaps we are especially vulnerable to the advertising messages that promise us a relationship with an addictive product.

In the beginning, most addictions seem to fill us with zest and vitality and advertising often plays on this. “Alive with pleasure” and “Fire it up!” say the cigarette ads, while a beer ad proclaims, “Grab for all the gusto you can,” as if a product that eventually numbs many of us could help us live more intensely. “Pursue your passion and new possibilities will awaken,” claims an ad for Scotch. A gin ad features a man blissfully swimming in a sea of alcohol, with the caption “Innervigoration.” Since gin is a clear drink, a huge lemon slice provides the glow, the amber light.

We feel empowered to act by our addictions, often foolishly or rebelliously. “Yes, I can!” say a cigarette ad. “Anything can happen,” claims a campaign for tequila, featuring young happy people in glamorous outdoor settings. Yet the ads promise us that the only results of such impulsiveness will be adventure and romance. What happens in the ads, of course, is always wonderful—picnics on the beach at sunset, hang-gliding. Even though most of us know, on some level, that the surprises that accompany drinking are not usually so pleasant, the ads are still seductive.

In a commercial for Zima, a malt-based alcohol, a young woman sits at an airport bar, her flight to Minneapolis delayed. The bartender pours her a Zima, she takes a sip, she hears the announcement of a flight to Paris, and she spontaneously departs for the City of Light (fortunately, she must have had her passport on hand). The Zima is her magic carpet.

The promise always is that the surprise will be happy—a flight to Paris as opposed to a car crash, falling in love rather than being raped on a date, winning the lottery as opposed to getting AIDS from unprotected drunken sex. Or, less dramatically, picnicking on a beach at sunset rather than throwing up at midnight, being the life of the party as opposed to insulting the host.

“Your night is about to take an unexpected twist,” promises an ad for gin. One is supposed to think of adventure, not embarrassment, certainly not catastrophe.

Alcohol gives us the illusion of clarity. “In vino veritas,” we are told. Alcohol sometimes loosens our tongues so we can speak the truth, but for alcoholics it far more often makes us project our grief and self-hatred onto those closest to us. Through a combination of denial and projection, alcoholism prevents us from seeing the truth about ourselves or our loved ones. And yet sometimes alcohol is very directly advertised as a way to achieve clarity. A scotch ad headlined “Vision” continues, “Seeing clearly is the first step towards acting decisively,” as if the drink would contribute to this.

As always, the mythology presented in the alcohol ads is exactly the opposite of the truth about alcohol. Again and again, alcohol is advertised as a way to enhance communication. One ad says, “If the world’s biggest problem is a lack of communication, might we suggest a corner table and a fine scotch.” Another, featuring a young couple walking together, promises “the art of conversation” along with the cognac.

With enough alcohol, the ads tell us, conversation can be dispensed with altogether: “You must be reading my mind” is the caption over a picture of another young couple walking arm in arm on a cobblestone street, beneath golden gaslights.

“Can the generation gap be bridged?” asks another ad, which concludes that perhaps the right kind of scotch can bridge it. Of course, the truth is that alcohol is far more likely to widen gaps between people than to bridge them.

“I love you, man,” says a son to his father while the two are fishing in a very successful Bud Light commercial. However, it turns out he just wants his father’s beer and his father snaps back, “You’re not getting my Bud Light.”

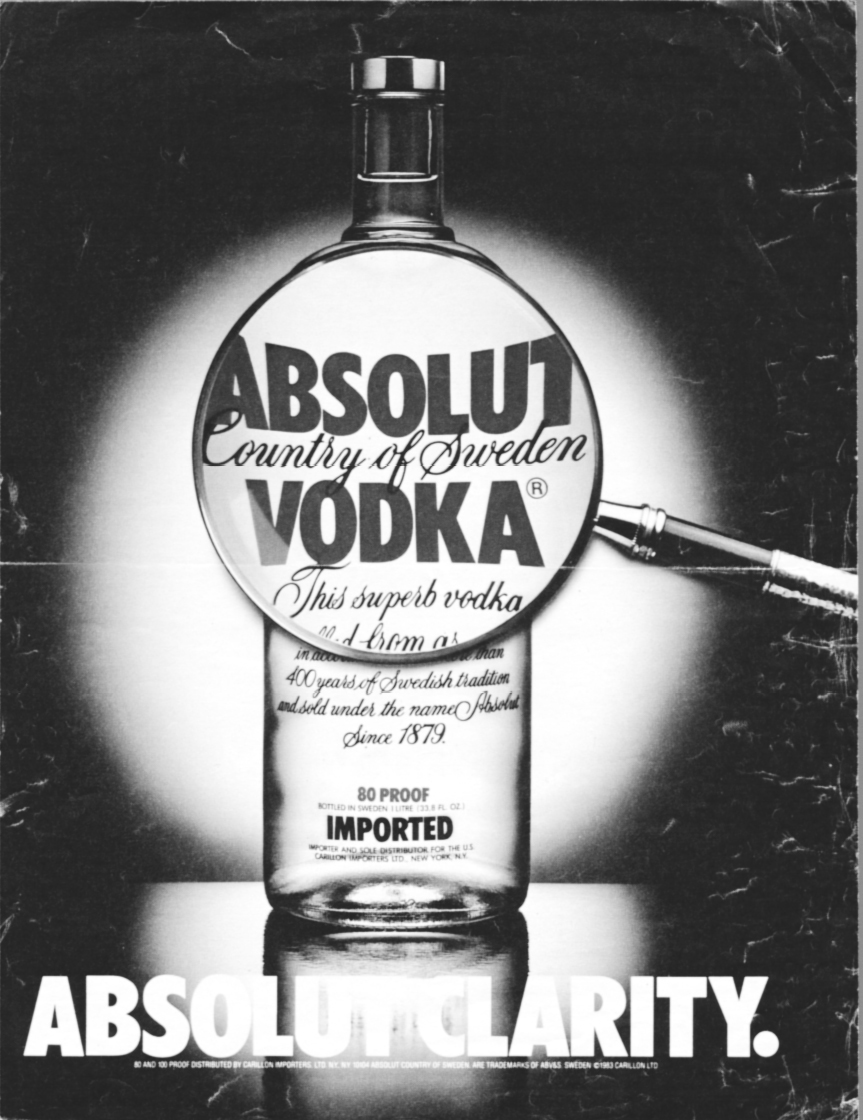

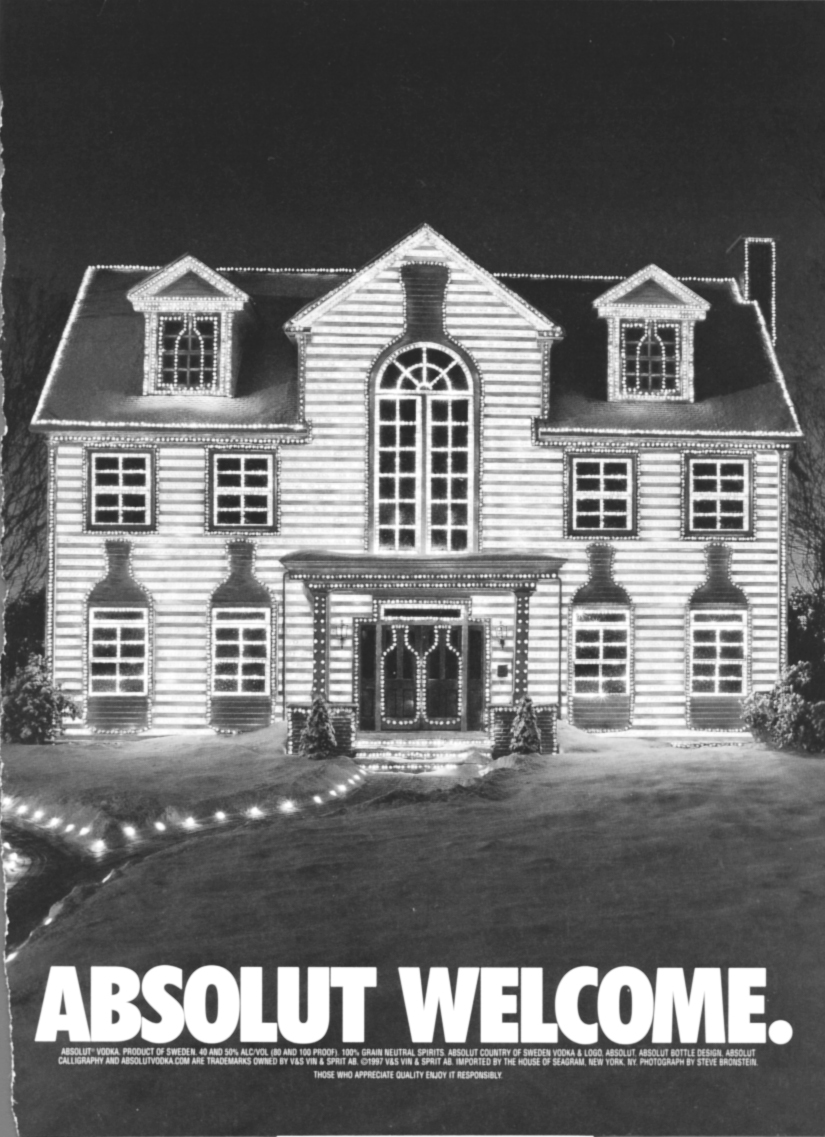

“We sat, my father and I, and indulged in fine cigars and the taste of Pinch. Then we did something we rarely do. We talked,” says a scotch ad, one of many in which advertisers offer alcohol as a route to intimacy. The promise of better communication between parents and children is particularly ironic given the devastating effects of parental alcoholism on children and families. Alcohol is involved in over half of all cases of domestic violence and child abuse, and alcoholic families are usually marked by denial and silence (interrupted in many families by emotional and physical explosions, but not by communication). Yet the bottle often represents home itself, as in a Smirnoff vodka campaign with the slogans, “Home is where you find it,” and, “Isn’t it funny how so many of the places we find Smirnoff feel like home?” “Home improvement,” claims an ad for Bacardi rum, while a beer ad tells us that “a man’s beer is his castle.” Indeed. Almost any child of an alcoholic would find the Absolut ad featuring every window and door of a house in the shape of a bottle an unintentionally ironic picture of the huge and destructive role that alcohol so often plays in families. More accurate, albeit unintentionally, is a rum ad that says, “The dark taste that eclipses everything.”

Any kind of addiction gets in the way of communication, mostly because the addict is so focused on the substance. A woman in an ice cream ad says, “I was talking to my boyfriend as I unwrapped my Häagen-Dazs Vanilla Almond Bar. Slowly his voice started to drift away. Completely consumed, I carefully licked the thick Belgian chocolate off. Then I immersed myself in the creamy center. Of all the wonderful things I can say about Häagen-Dazs, I can’t say it’s great for conversation.”

Of course, food and drink can be wonderful for conversation. It somehow seems easier to have intimate conversations while sharing something to eat or drink, a glass of wine, a caffe latte, a good meal. I remember the taste of the chicory in the coffee and the powdered sugar on the beignet as I talked with a friend in New Orleans, a few years after I got sober, about my childhood. “You must have thought you were a bad person,” she said and, at that moment, I realized that I had thought that for a long, long time but I no longer did. I realized, as I savored the rich taste of the coffee and the southern sun warm on my skin and the compassionate perceptiveness of my friend, that I was happier than I had ever expected to be.

However a glass of wine might enhance a conversation, a bottle of wine will make it at best difficult to recall. When the food or the alcohol or any addictive substance becomes the focal point, relationships inevitably suffer. Countless children grow up with parents whose attention is tragically diverted by an addiction.

Through the miracle of denial, alcohol seems to increase our sense of self-worth, but in fact it mires us more deeply in our self-hatred. “Love thyself,” says an ad for scotch, one of many ads offering alcohol as a reward, a gift for oneself. “I.O. ME” declares a billboard ad for whiskey. Ads often offer us alcohol and food as richly deserved rewards, whatever the occasion. It takes an enormous amount of energy to maintain the kind of denial necessary to protect an alcoholic from his or her self-loathing. It is so painful to face the deep belief that one is worthless, unlovable, that many alcoholics, especially male alcoholics, seek refuge in grandiosity—which is, after all, a form of self-hatred. The alcohol advertisers know this—and play on it in ad after ad.

Finally, what is addiction if not a desire for more connection? Unfortunately, it is a connection that makes human connection and real intimacy difficult, if not impossible. “More . . . more . . . more . . . gin taste,” one ad declares. More gin taste simply means more gin, of course. “More” is even the name of a cigarette brand. “Absolut Attraction,” says an ad featuring a cocktail glass leaning toward a bottle of vodka. People are not even present and yet the ad still implies a promise of greater connection.

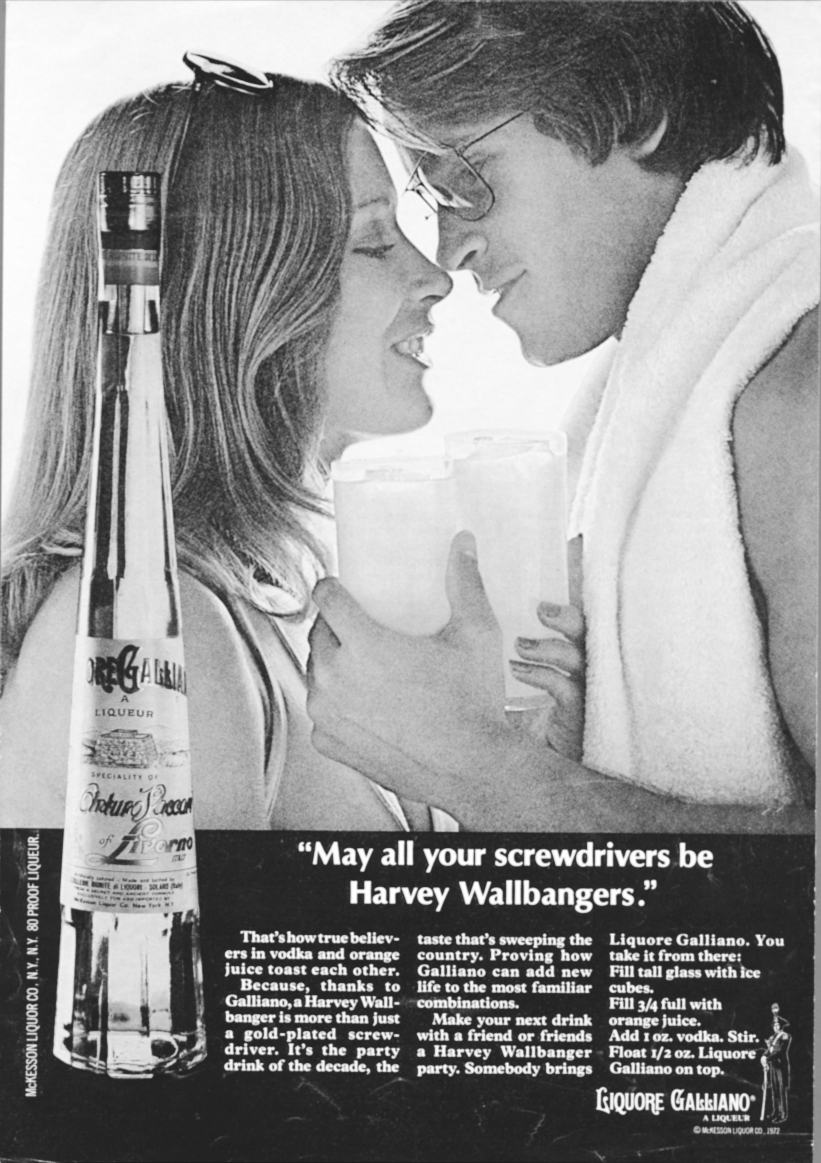

Most often, the intimate connection that the alcohol ads offer is a sexual experience. Countless ads feature couples passionately embracing, with suggestive copy such as, “May all your screwdrivers be Harvey Wallbangers,” “Wild things happen in the ‘oui’ hours,” and, “Is it proper to Boodle before the guests arrive?” “If the French can do this with a kiss . . .,” asks an ad featuring a man passionately kissing a woman’s neck, “imagine what they can do with a vodka!” Given that the vodka is called Grey Goose, I hate to think.

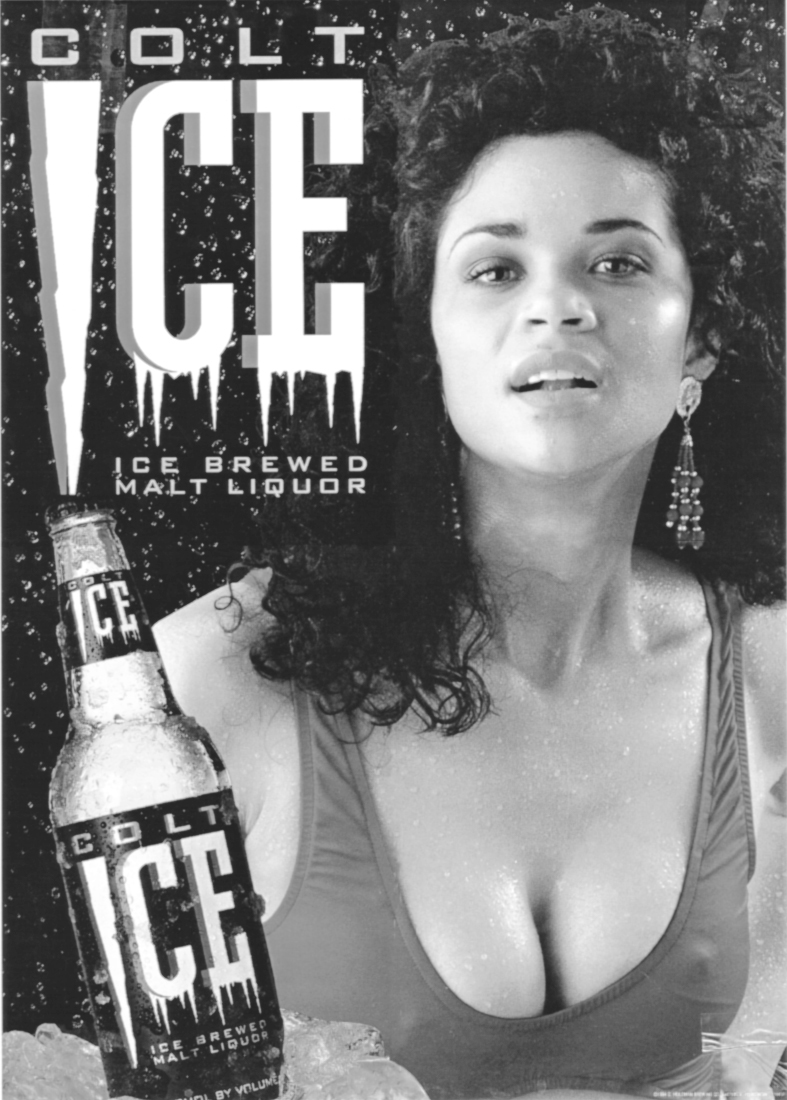

Of course, alcohol has long been advertised to men as a way to seduce women. An ad for Cherry Kijafa from the 1970s features a virginal young woman dressed entirely in white and the headline “Put a little cherry in your life.” Such double entendres abound, ranging from a cocktail called “Sex on the Beach” to an ad featuring a young man dressed as a fencer declaring, “I’m as sure of myself on each thrust as I am when choosing my scotch.” In a series of suggestive print and television ads in the 1980s, Billy Dee Williams promised that Colt 45 malt liquor “works every time.” Years later a radio ad, also for malt liquor and also targeting young African-American men, said, “Grab a six-pack and get your girl in the mood quicker. Get your jimmy thicker with St. Ides malt liquor.” Imagine—our kids are growing up in this kind of environment and some people think it’s enough to tell them to “just say no” to sex. “Get your jimmy thicker” but keep it in your pants?

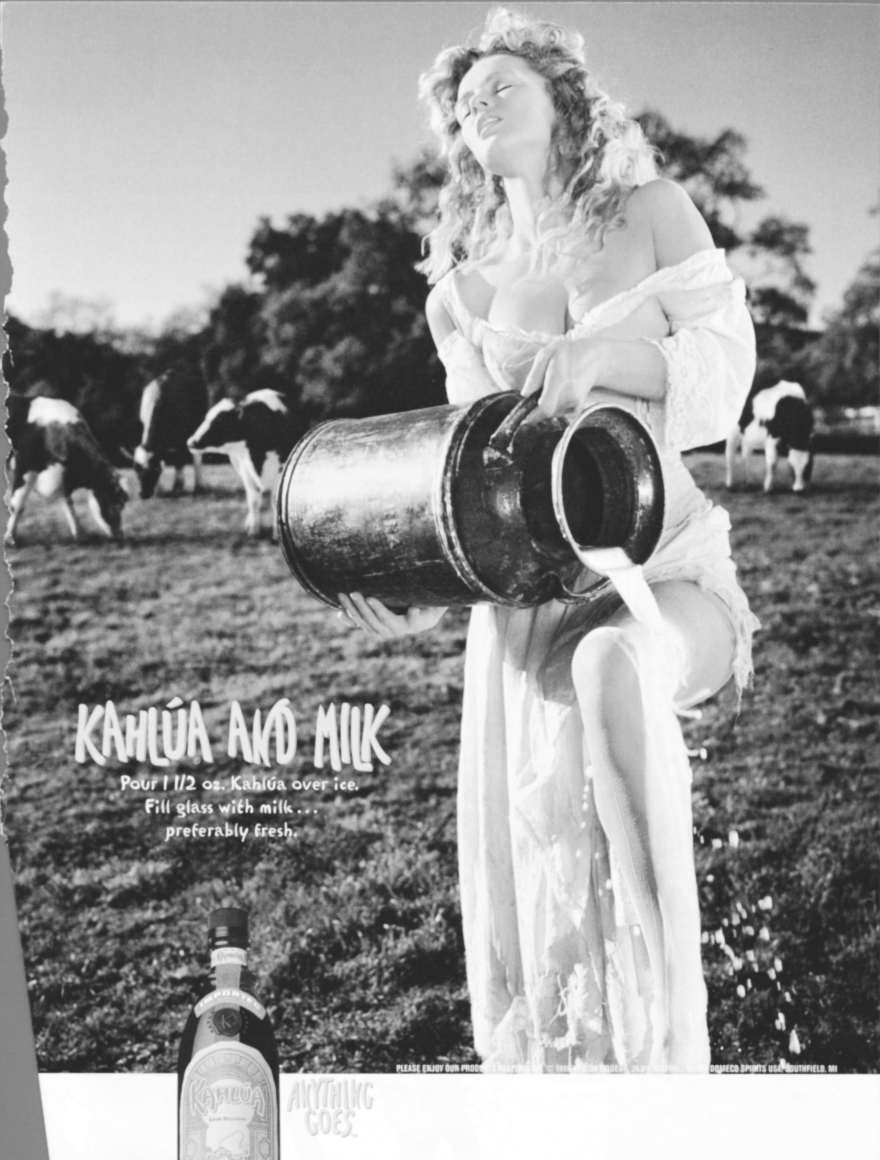

An extremely erotic 1999 ad for Kahlua pictures a milkmaid lasciviously pouring milk all over her leg. Her head is tossed back and her eyes closed, as if she were in the throes of orgasm. The goosebumps on her leg are obvious as is the erect state of her exposed nipple. “Anything goes” is the tagline.

Using sex to sell alcohol certainly isn’t new. What is new in recent years is the promise in alcohol ads of a sexual relationship with the alcohol itself. No longer a means to an end, the drink has become the end. “You never forget your first girl” is the slogan for St. Pauli Girl’s beer. “Just one sip of St. Pauli Girl’s rich, imported taste is the start of a beautiful relationship.” “Pilsner is a type of beer,” says an ad featuring a beautiful young woman, “kind of like Rebecca is a type of woman.” The ad concludes that it would be great to meet either one in a bar.

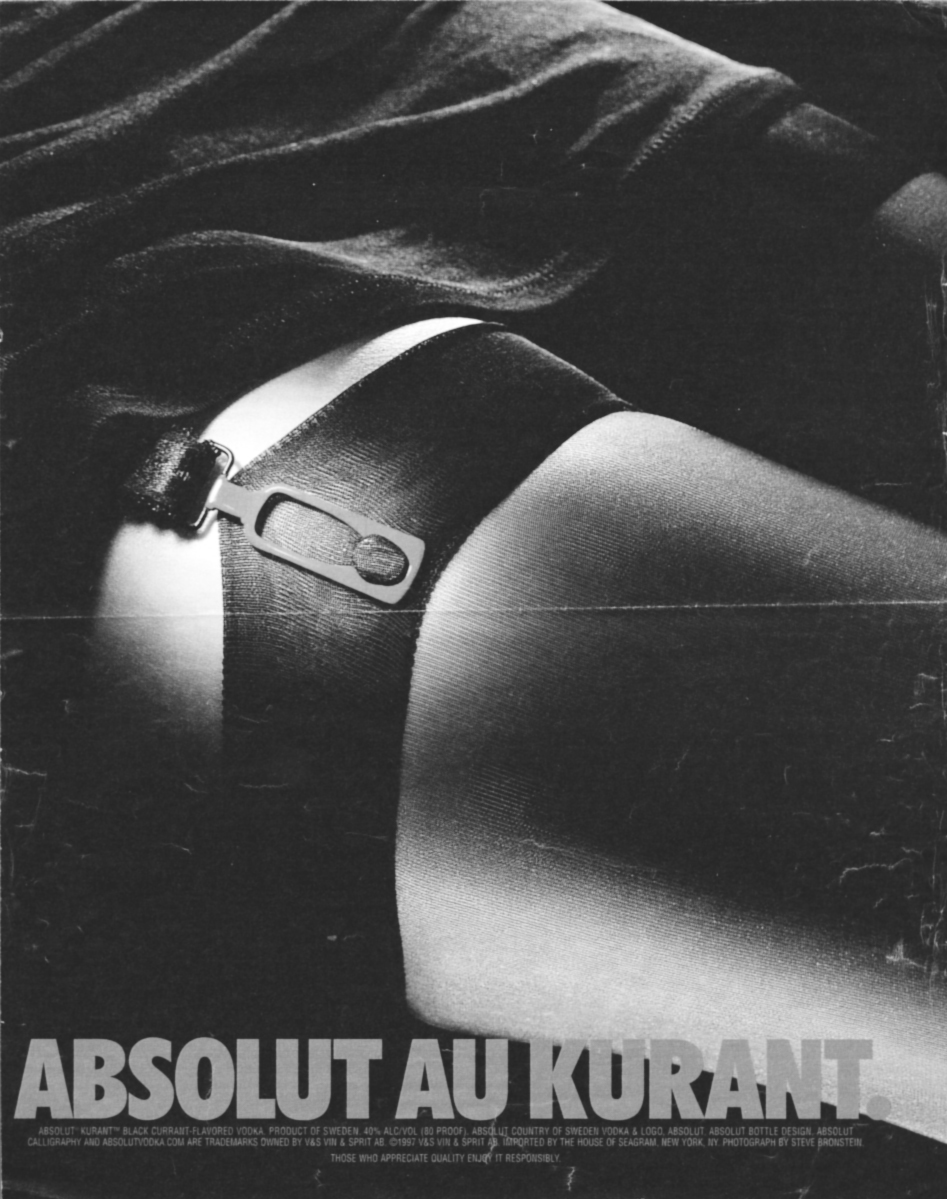

“Six Appeal” is the slogan for an ad that features a six-pack of beer and the copy, “The next time you make eye contact with a six-pack of Cold-Filtered Miller Genuine Draft Longnecks, go ahead and pick one up. You won’t be disappointed!” In a 1998 Bud commercial, a group of women are standing in a bar and, nodding toward some leering guys, talk about how men think about “it” every eight seconds. But it turns out that the guys are ogling bottles of Bud. An Absolut ad features the top part of a woman’s leg clad in a black silk stocking with a garter in the familiar shape of the Absolut bottle. This focus on one part of the female body, this dismemberment, is common in ads for many products, but especially so for alcohol. The image draws men in, but there is no person, not even a whole body, to distract them from the focus of the ad, the bottle.

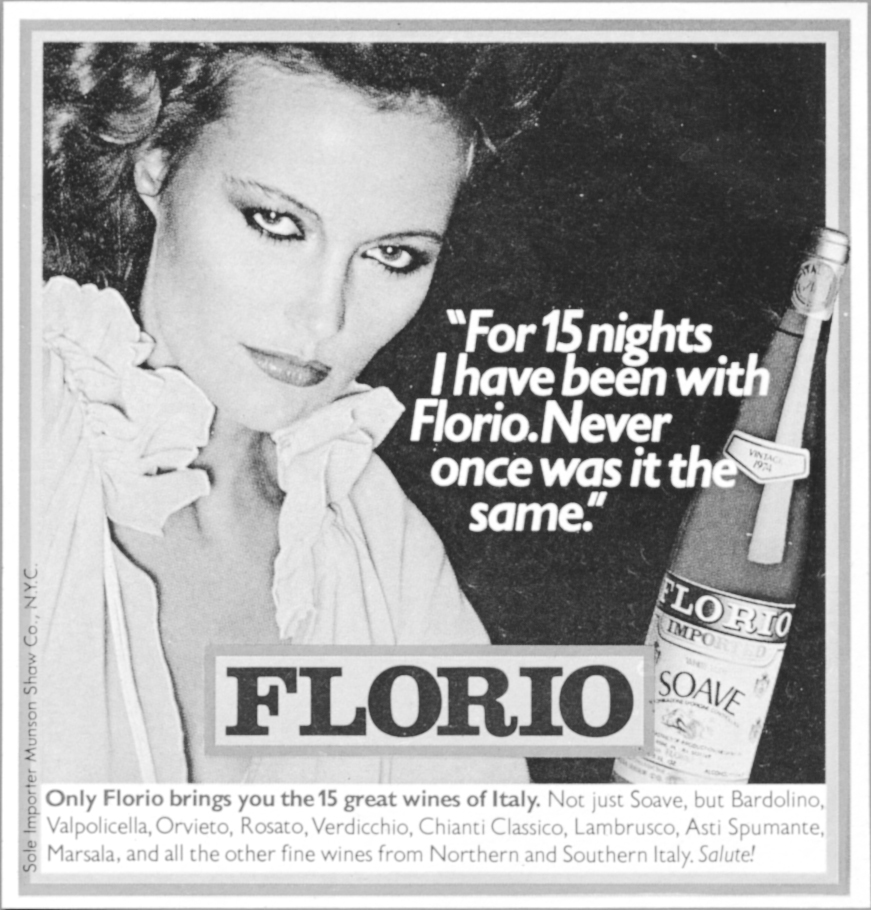

Women are increasingly encouraged to think of the bottle as a lover too. “If your man won’t pour, I will,” says an ad for cognac which features the bottle rakishly leaning toward the woman. Another ad pictures a bottle of whisky in a drawstring pouch with the tagline “Smooth operator.” In an ad for an Italian wine called Florio, a beautiful and sultry woman says, “For 15 nights I have been with Florio. Never once was it the same.” This reminds me of a joke I used to make about my drinking years—that perhaps I had had the same conversation every night over and over again and just didn’t know it!

In the early 1980s Campari ran a series of ads featuring celebrities such as Geraldine Chaplin and Jill St. John talking lasciviously about their “first time.” “There are so many different ways to enjoy it,” Chaplin says. “Once I even tried it on the rocks. But I wouldn’t recommend that for beginners.” The sophomoric campaign used the slogans, “The first time is never the best,” and, “You’ll never forget your first time.” One of the ironies of this campaign is that alcoholics usually do remember their first drink and often romanticize it. For this reason, there’s a saying among alcoholics that we should remember our last drunk, not our first drink.

A rawer version of the sexualization of the product was a campaign for the subtly named Two Fingers tequila. Every ad in the campaign featured an older man caressing a beautiful younger woman and saying such things as, “This woman, she is like my tequila. Smooth, but with a lot of spirit,” and, “Señor, making good tequila is like looking for a good woman.” One of the ads further describes the woman as “the only other love Two Fingers had besides his tequila.” Given their age difference, it seems that Two Fingers spent most of his life in love with tequila.

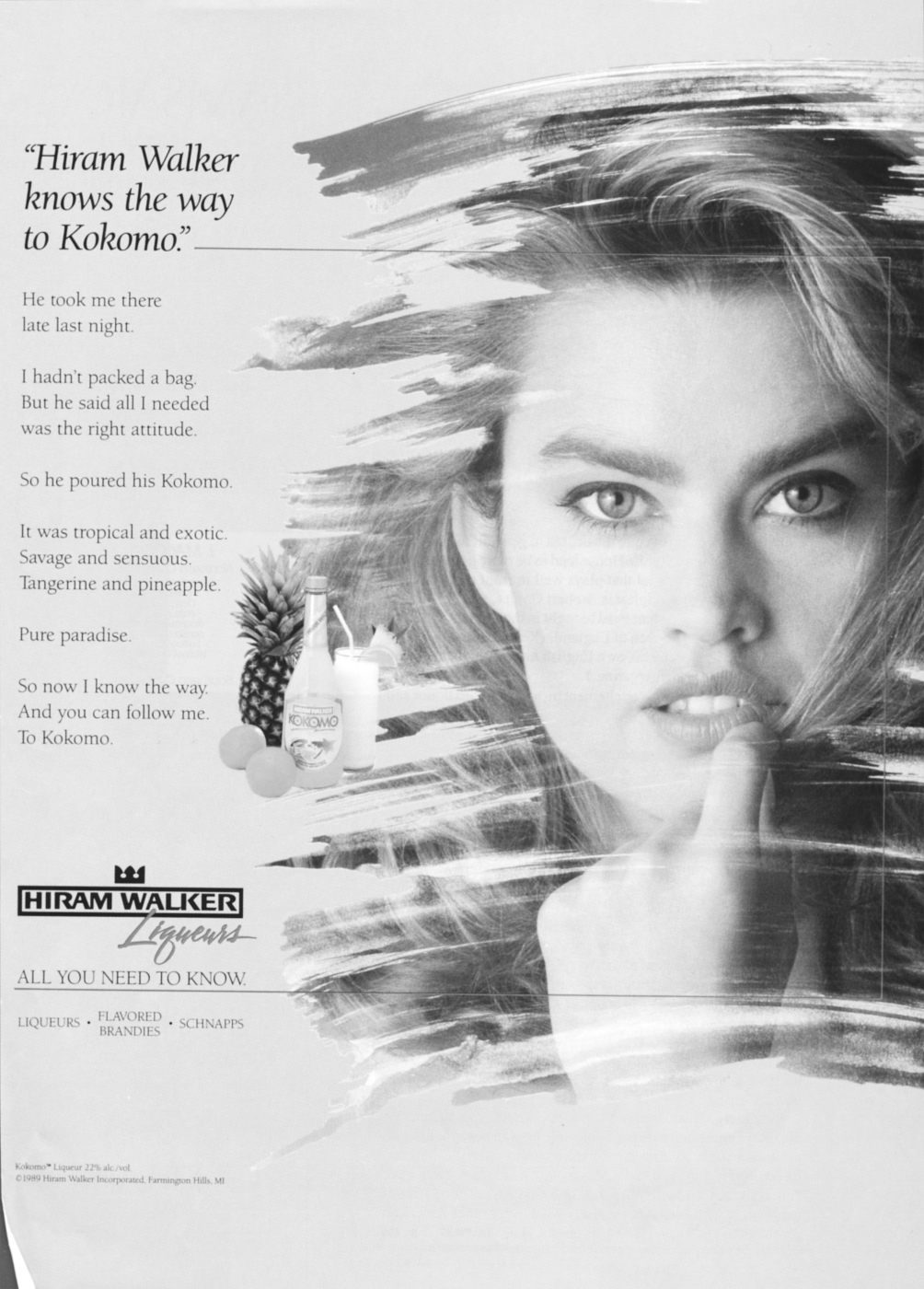

A strange campaign for Hiram Walker liqueurs personifies the product in a series of ads. In one a beautiful young woman says, “Hiram Walker knows the way to Kokomo.” She continues, “He took me there late last night. I hadn’t packed a bag. But he said all I needed was the right attitude.” Another ad in the campaign features a fairly distraught young man saying, “Who is this Hiram Walker guy anyway?” He goes on to say, “My girlfriend couldn’t stop talking about him. ‘He’s spirited . . . and sophisticated . . . and fun. Everything a man should be!’ I said, ‘Listen, it’s him or me. Make up your mind.’ She said, ‘I want you both.’” The young man ends up having some Hiram Walker, saying, “If you can’t beat him, join him.” Sadly, this is an attitude many people adopt when dealing with alcoholics.

In this case, the man is introduced to the drink by the woman. Usually, in life and in advertising, it is the other way around. Women and girls are usually introduced to alcohol and other drugs by their boyfriends, who generally are older and more experienced. Women often use the drugs to please their men, to have a common activity, or simply to make the relationship bearable.

The advertisers sometimes encourage women to drink in order to keep company with drinking men. “Share the secret of Cristal,” says a beautiful woman. The copy continues, “The Colombians kept it to themselves. Men mostly drank it straight. I thought it was pretty tough stuff ‘til the night I met him in Miami and he persuaded me to try CRISTAL & O.J. on ice. Very nice!” Often, as in this ad, the man is urged to drink the product straight while the woman is encouraged to cut it with juice, orange juice in this case, or soda (a more “feminine” approach).

The increasing sexualization of alcohol in ads parallels the progression of the disease of alcoholism, in which alcohol plays a more and more important role. Alcohol is used initially by many people as an attempt to increase confidence, especially sexual confidence, and for some a drink or two can lead to greater relaxation and less inhibition (although intoxication usually reduces sexual responsiveness). For the alcoholic, however, alcohol eventually becomes the most important thing in life and makes other relationships, including sexual relationships, more difficult, if not impossible. Thus, the ads move from a soft-core promise of sexual adventure and fulfillment with a partner to a more hard-core guarantee of sexual fulfillment without the trouble of a relationship with a human being. Alcohol becomes the beloved. And when alcohol is the beloved, relationships with people—with lovers, children, friends—suffer terribly.

One of the most chilling commercials I’ve ever seen is a 1999 one for Michelob. It opens with an African-American man and woman in bed, clearly just after making love. A fire is blazing and romantic music is playing. “Baby, do you love me?” the woman asks. “Of course I do,” the man replies. “What do you love about me most?” she asks. The man looks thoughtful, “Well, Michelob, I love you more than life itself.” “What did you call me?” the woman asks indignantly. “I called you Theresa,” he replies. “No, you did not,” she says, leaping from the bed, “You just called me Michelob. I’m outta here.” “Wait, wait,” the man says. “What?” she asks. “While you’re up,” the man says, “could you get me a Michelob?” On the surface, this commercial is intended to be funny, of course. But on a deeper level, and I believe intentionally on the part of the advertisers, it is meant to normalize and trivialize a symptom of alcoholism. The terrible truth is that alcoholics do love alcohol more than the people in their lives and indeed more than life itself.

The Black Velvet campaign of the late 1970s and early 1980s featured a beautiful blonde wearing a sexy black velvet outfit seductively inviting the viewer to “Feel the Velvet” or “Touch the Velvet” or “Try Black Velvet on this weekend.” A few years ago, a product called Nude Beer went further and featured a bikini-topped model on the label. The bikini top could be scratched off, revealing her bare breasts. Even then, however, although the woman was a symbol of the alcohol, the focus was still on her.

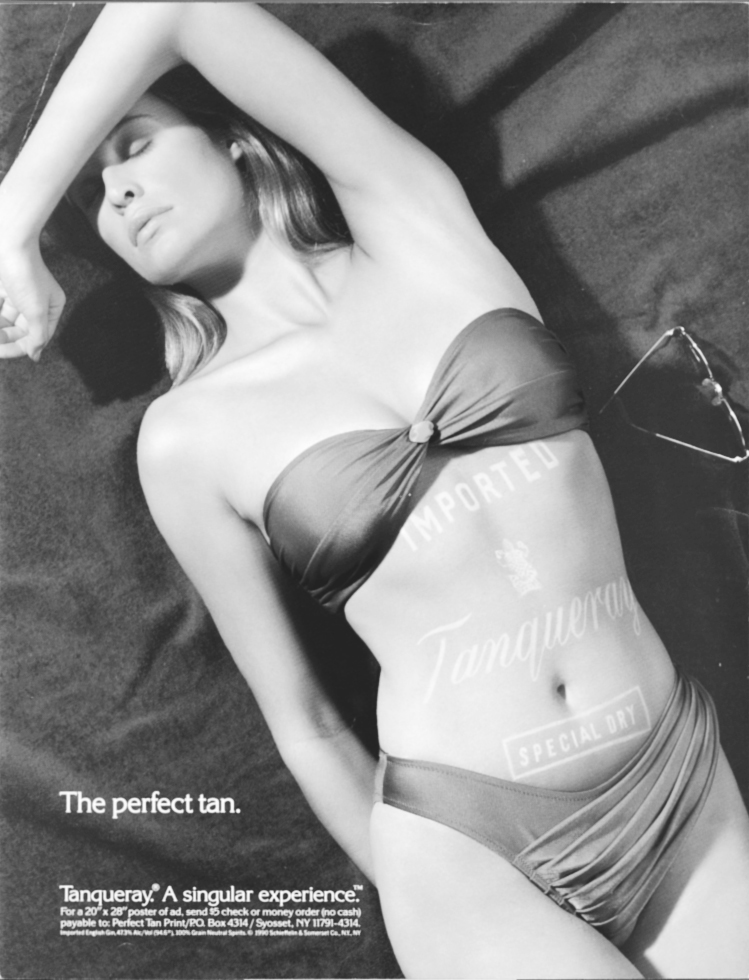

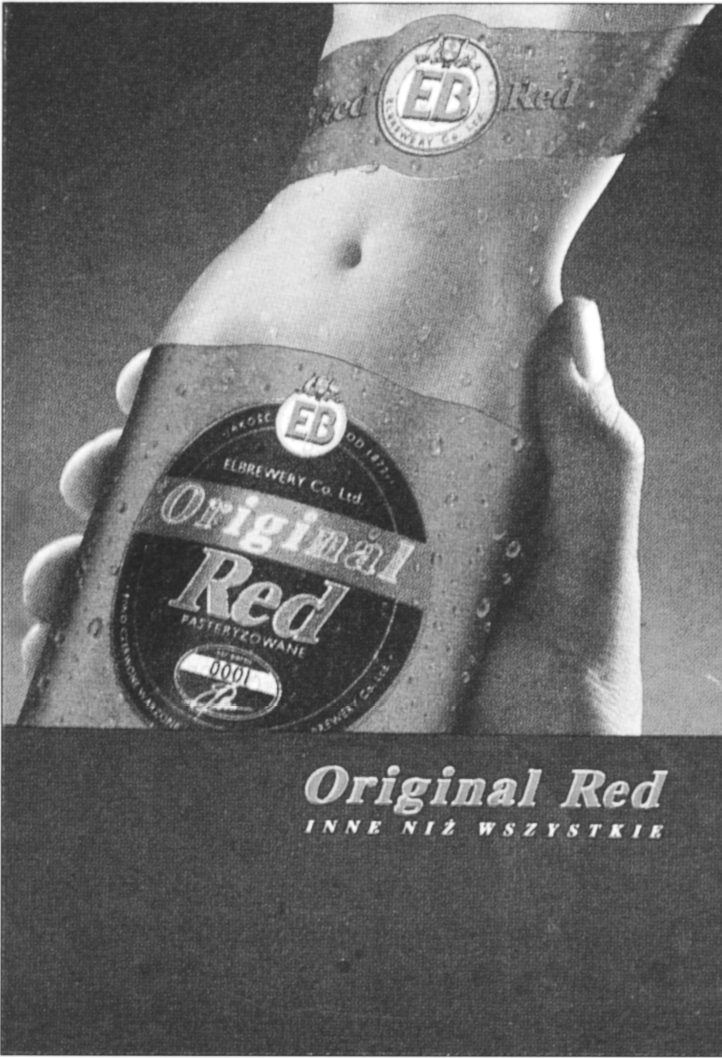

In recent years, women’s bodies in alcohol ads are often turned into bottles of alcohol, as in a Tanqueray gin ad in which the label is branded on the woman’s stomach. A beer ad shows cases of Miller Lite stacked (so to speak) on a beach, with the headline “The perfect 36–24–36.” There are women in bikinis in the background, but clearly the headline refers to the numbers of cans of beer. “The best little can in Texas” pictures a close-up of a woman’s derriere with a beer can held up against it. In these cases, the woman is the intermediary. Sometimes the bottle literally becomes the woman, as in an Original Red ad. At least in these ads, a real woman is present to some degree, although objectified and dismembered. In many alcohol ads these days, the woman is completely dispensed with and the bottle itself is sexualized. A college poster advertising beer features a glass of beer and the caption, “Great head, good body.”

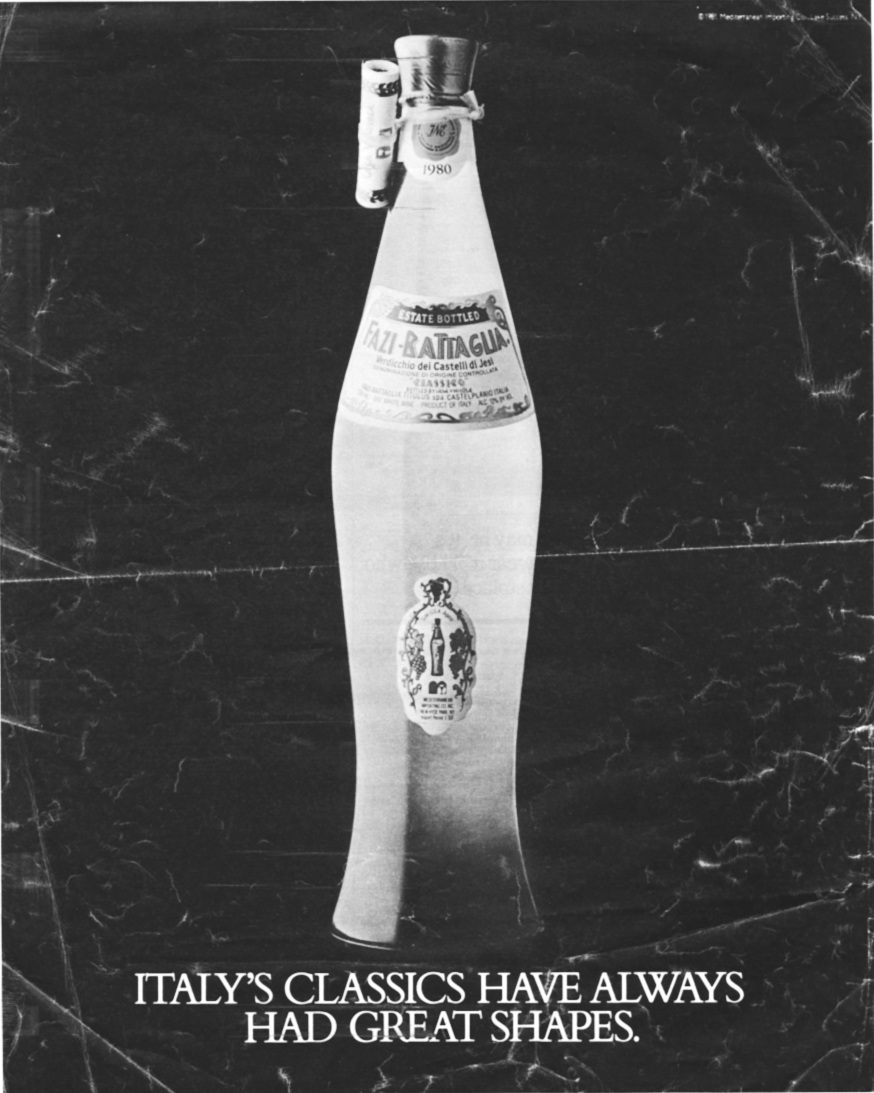

“Italy’s classics have always had great shapes,” declares an ad spotlighting a curvaceous bottle of an Italian liqueur. “Not exactly for the bourbon virgin,” says an ad for Knob Creek bourbon featuring an extreme closeup of the bottle with an emphasis on the word “pro” within “proof” (this campaign was so successful, it increased sales by 55 percent). “You’d even know us in the nude,” says an ad for scotch, which features a man’s hand suggestively peeling back the label from the bottle. Again, the promise is that the alcohol alone will provide a fulfilling relationship, even a sexual relationship—nothing else is necessary.

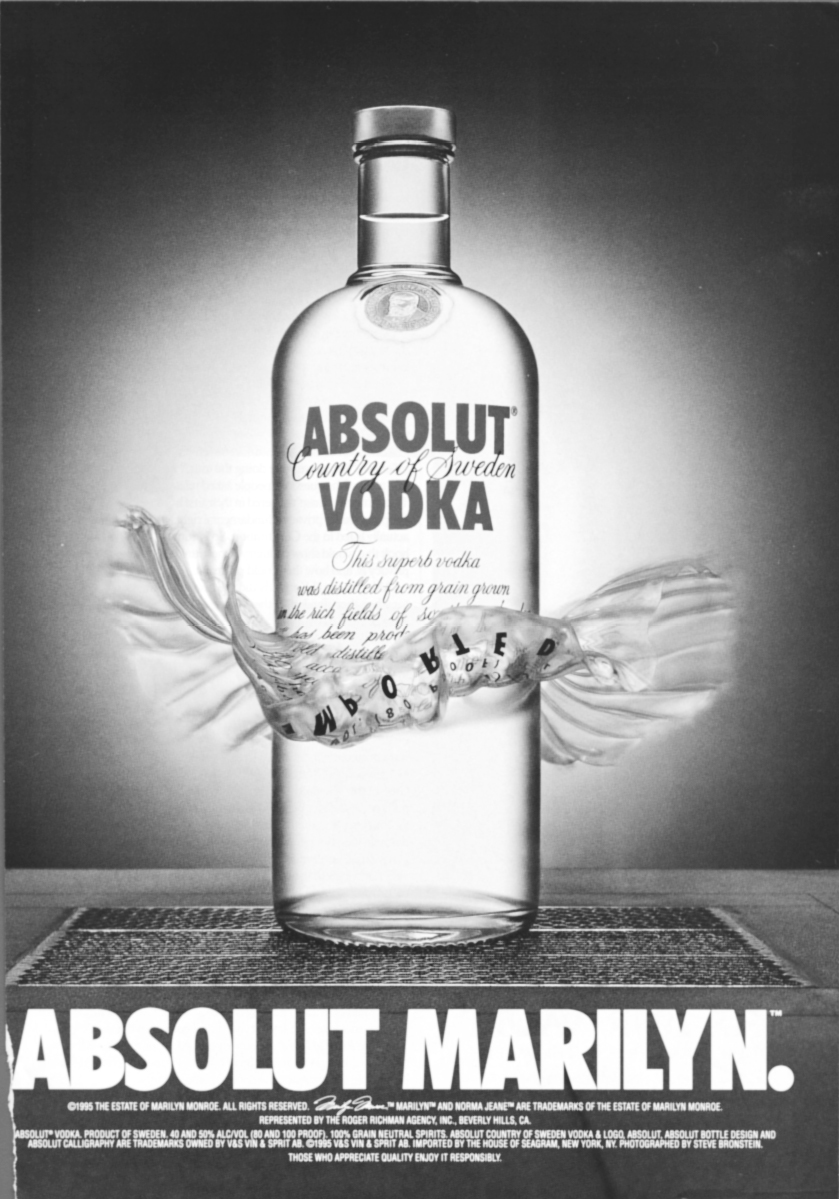

The popular Absolut campaign has several ads in which the bottle is sexualized, including “Absolut Centerfold,” which features the bottle without its label, and “Absolut Marilyn,” in which the bottle symbolizes Marilyn Monroe in her famous dance above the grating.

“A few insights into the dreams of men,” says an ad that features four cartoon men dreaming of a bottle of whiskey. “Yes, men dream in color” is the caption above the first man, referring to a drawing of the bottle in a colorful velvet sack. “The average male only remembers 62% of his dreams,” is above the second man and the bottle is one-third gone. “5% of all men have a recurring nightmare” is the caption for a picture of an empty bottle. “Every man gets aroused at least once per night,” depicts a case of whiskey. Women don’t exist in this ad, even in the dreams of men. Preoccupation with alcohol is one of the signs of alcoholism. Some alcoholics don’t drink all that much, but all alcoholics think about drinking a lot of the time. This ad, in its funny, lighthearted way, normalizes this preoccupation. But the truth is that people who are preoccupied with alcohol create nightmares for themselves and others.

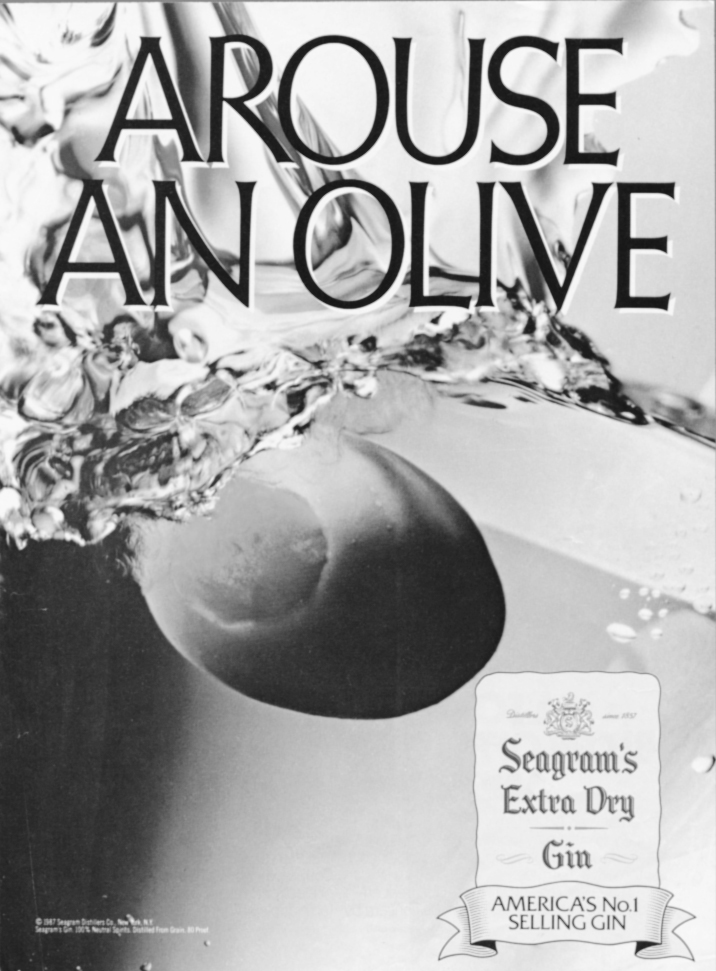

Sometimes it is the drink that is sexualized rather than the bottle. “Peachtree excites soda,” proclaims a liqueur ad. A series of ads for Seagram’s Extra Dry Gin features extreme closeups of the gin in a glass with an olive, a piece of lemon, and a cherry with the bold headlines, “Arouse an olive,” “Tease a twist,” “Unleash a lime,” and “It’s enough to make a cherry blush.”

Even the cork sometimes gets into the act, as in a liqueur ad featuring a phallic cork and the words “It’s not a stopper. It’s a starter.” Such suggestiveness might seem silly and trivial or unconscious, as perhaps it sometimes is. However, given the money and energy that advertisers spend on psychological research and the undeniable usefulness of linking sex and power with a product, I contend that most of these visual and verbal puns and symbols are intended by the advertisers as yet another cynical ploy to influence us.

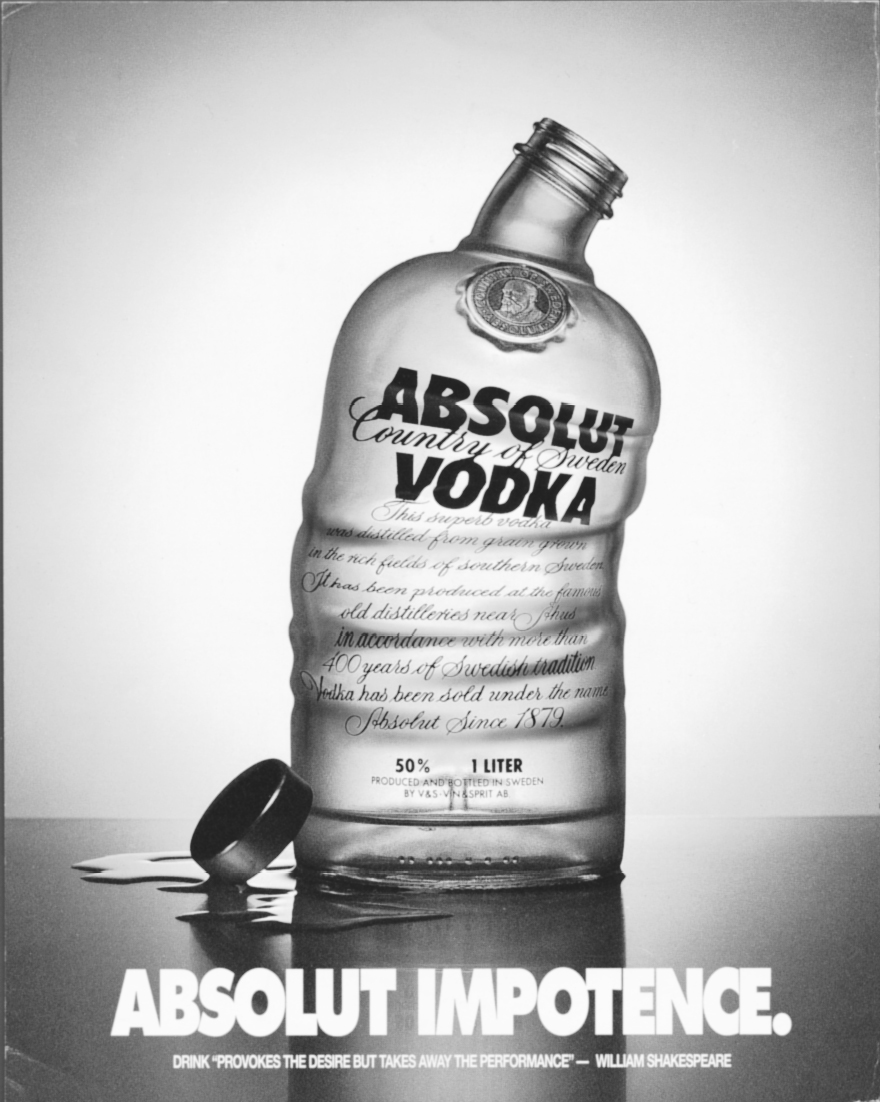

Ad after ad promises us that alcohol will give us great sex. The truth is exactly the opposite. Not only do high-risk quantities of alcohol often lead to sexual dysfunction, for women as well as for men, but they are also linked with other unwanted consequences, such as date rape, unwanted pregnancy, fetal alcohol syndrome, and sexually transmitted diseases, including AIDS. Alas, the parody “Absolut Impotence” comes closer to the real relationship between alcohol and sex. Perhaps Shakespeare put it best when he said that drink “provokes the desire, but it takes away the performance.”

Again and again, advertising tells us that relationships with human beings are fragile and disappointing but that we can count on our products, especially our addictive products. A Winston ad features a greeting card that says, “I never really loved you,” with the tagline, “Maybe there shouldn’t be a card for every occasion.” Another ad in the same campaign shows a cocktail napkin with a woman’s name and phone number written on it. The copy says, “Please check the number and dial again.” Oh well, at least we’ve got our cigarettes.

In truth, addiction increasingly corrupts and co-opts every desirable outcome of real connection. The initial sense of zest and vitality is replaced by depression and despair. Our ability to act productively is severely impaired and our lives stagnate. Blinded by denial, we are unable to see ourselves or others clearly. Corroded with self-hatred, we poison our relationships and end up alienated and alone. Our world narrows as our relationship with alcohol or another drug or substance becomes our central focus. We spiral downward.

Recovery reverses this downward spiral, widening our world and our possibilities. As we break through denial and learn to be honest with ourselves and others, our clarity and our sense of self-worth dramatically increase. All of this leads to a desire for more connection, both with other people and with some kind of life force. We find in recovery everything we had longed to find in addiction—but what addiction had in fact taken from us.

Denial blinds us to the many ironies of addiction, and advertising often supports this denial. In the case of alcohol, we drink to feel glamorous and sophisticated and often end up staggering, vomiting, screaming. We drink to feel courageous and are overwhelmed by fear and a sense of impending doom. We drink to have better sex, but alcohol eventually makes most of us sexually dysfunctional. We do this to ourselves because of our disease, but we also do it in a cultural climate in which people who understand the nature of our disease deliberately surround us with powerful images associating alcohol with glamour, courage, sexiness, and love, precisely what we need to believe in order to stay in denial.

Above all, we drink to feel connected and, in the process, we destroy all possiblity of real intimacy and end up profoundly isolated. Sadly, it is perhaps in recognition of this fact that advertisers so often romanticize and sexualize the bottle. Addicts often end up alone or in very dysfunctional relationships. We turn to alcohol or other drugs or activities for solace, for comfort, for the illusion of intimacy, and even for the illusion of sex appeal or sexual fulfillment. As addiction disrupts our human connections, the substance becomes ever more important, both to numb the pain and to continue the illusion that we are doing all right. What begins as a longing for a relationship, a romance, a grand passion, inexorably ends up as solitary confinement.