“RELAX. AND ENJOY THE REVOLUTION”

Redefining Rebellion

![]()

WE LIVE IN A TOXIC CULTURAL ENVIRONMENT. OUR CHILDREN ARE BEING grossly exploited for commercial gain, buried alive in what David Denby so accurately calls “an avalanche of crud.” Millions of people are suffering in the prison of addiction, while others profit from their misery. What can we do about this? How can we break through the climate of denial? The first thing we must do is to get past the cultural belief, promoted so heavily by advertising, that there is a quick fix, an instant solution to every problem—and that one shouldn’t even discuss a problem unless one has this solution firmly in mind. There is no quick fix for the problems discussed in this book, no panacea, but there are many things we can and must do.

We must recognize that all of these problems—addictions, eating disorders, male violence (including battering and rape), child abuse, the increasing commercialization of the culture, the exploitation of children by advertisers, gun violence, and the objectification of women and girls—are related. We cannot solve these problems by treating them as separate issues. They are all public health problems and must be treated as such. The public health perspective teaches us that no illness is ever brought under control by treating only the casualties—by having ambulances at the base of the cliff. Just as we can’t solve the problems of the physical environment by treating the cancer with chemotherapy, by removing the oil bird by bird, by developing better artificial limbs for the children born with arms and legs missing, we can’t solve the problems of the cultural environment by getting alcoholics into support groups, putting metal detectors in our schools, sentencing drunk drivers to stiff prison terms, creating patches and other devices to cut the craving for nicotine, or putting counselors specializing in eating disorders and dating violence in our schools and colleges.

Of course, we need to do some of these things and more to help the casualties. We must build more shelters and safe houses for battered women and children (as things stand now, we have more shelters for animals). We must get addicts into treatment, with separate kinds of treatment programs for adolescents, for girls and women, for prison inmates. We must change the focus of the war on drugs (which has been a dismal failure) from punishment to treatment and prevention. Two-thirds of the almost $18 billion federal drug control budget is spent on law enforcement and only one-third on prevention and treatment—although every person knowledgeable about addiction knows that the percentages should be reversed (and then some). Among industrialized nations, the United States is second only to Russia in the number of its citizens it imprisons, most for drug offenses.

Of course, we have to punish violent criminals, drunk drivers, and so forth. Addiction is not an excuse for criminal acts. But if we imprison people without treating them, we are just putting ourselves at greater risk. Treatment is not a reward for a criminal—it is a proven way to reduce recidivism and thus risk for the rest of us. We should insist that prison inmates be treated for addiction (and probably for post-traumatic stress syndrome, stemming from childhood, as well). This isn’t “coddling criminals”: This is acting in our own best interest.

Traditionally the approach to addiction in the United States has been consonant with our national ideology of rugged individualism and self-determination. The belief has been that a few unlucky people, through character flaws and general weakness, become addicted. As a culture, we tend to despise these people, just as we despise anyone (the poor, children, the disabled) who reminds us that we are all vulnerable and that no one is really independent. The solution has been to get addicts into treatment as individuals (or, in the case of the less popular drugs or the drugs used by African-Americans, to imprison them).

“Prevention” traditionally has also had an individual focus—“just say no,” resist peer pressure, and so forth. But how can we expect kids to say “no” to drugs, when their environment tells them “yes!” People make choices, for better or worse, in a physical, social, economic, and legal environment. The credo of individualism and self-determination ignores the fact that people’s behavior is profoundly shaped by their environment, which in turn is shaped by public policy. Certainly individual behavior and responsibility matter, but they don’t occur within a vacuum. The American tradition of individual responsibility and promise has been perverted to an extreme form of isolated individualism, an individualism no longer connected with active citizenship and community participation. The result is isolation, alienation, a failure to nurture the next generation or to care for the earth. As social critic Stanley Crouch said, “We get confused about the difference between heroic individuality, which makes possible a greater social freedom, and anarchic individuality, which is ruthless, narcissistic, amoral and dangerous. A long time ago, Alexis de Tocqueville suggested that America’s strength was also its vulnerability, that the nation’s vibrant individualism might in the long run “attack and destroy” society itself, for it can create individuals so atomized or self-involved that they “no longer feel bound by a common interest.”

Advertising’s point of view is always and necessarily extremely individualistic. The basic message of advertising, after all, is that an individual has a need or a problem that a product can meet or fix. We are constantly told by advertising that all we need to do is use the right products and get our own individual acts together and all will be fine. If we are unhappy, there is something wrong with us that can be solved by buying something. We can smoke a cigarette or have a drink or eat some ice cream. Or we can lose some weight (instantly, of course). If the problem is a headache, the solution is a stronger aspirin, rather than to question why we have so many headaches, what is going on in our buildings, our food, our environment, why we are so stressed. If the problem is lack of communication in our family, the solution is a different telephone service or a new kind of frozen dinner.

We are especially encouraged to stay focused on the individual and on small changes in personal behavior when the problems involve addiction. If you drink so much you wake up with a hangover . . . take an Alka-Seltzer, don’t worry about your drinking. If you’re afraid you might kill someone while you’re drinking and driving . . . get a designated driver. If you’re getting fat, the answer is to use a diet product, not to cut out the junk food and get off the couch. If your dieting is destroying your bones . . . take some calcium. If your teeth are rotting because you are bulimic . . . use a whitening gel. Don’t ever look at what this all might mean or try to put it in a larger context. That would disrupt the climate of denial that is so vitally important to the sellers of addictive products.

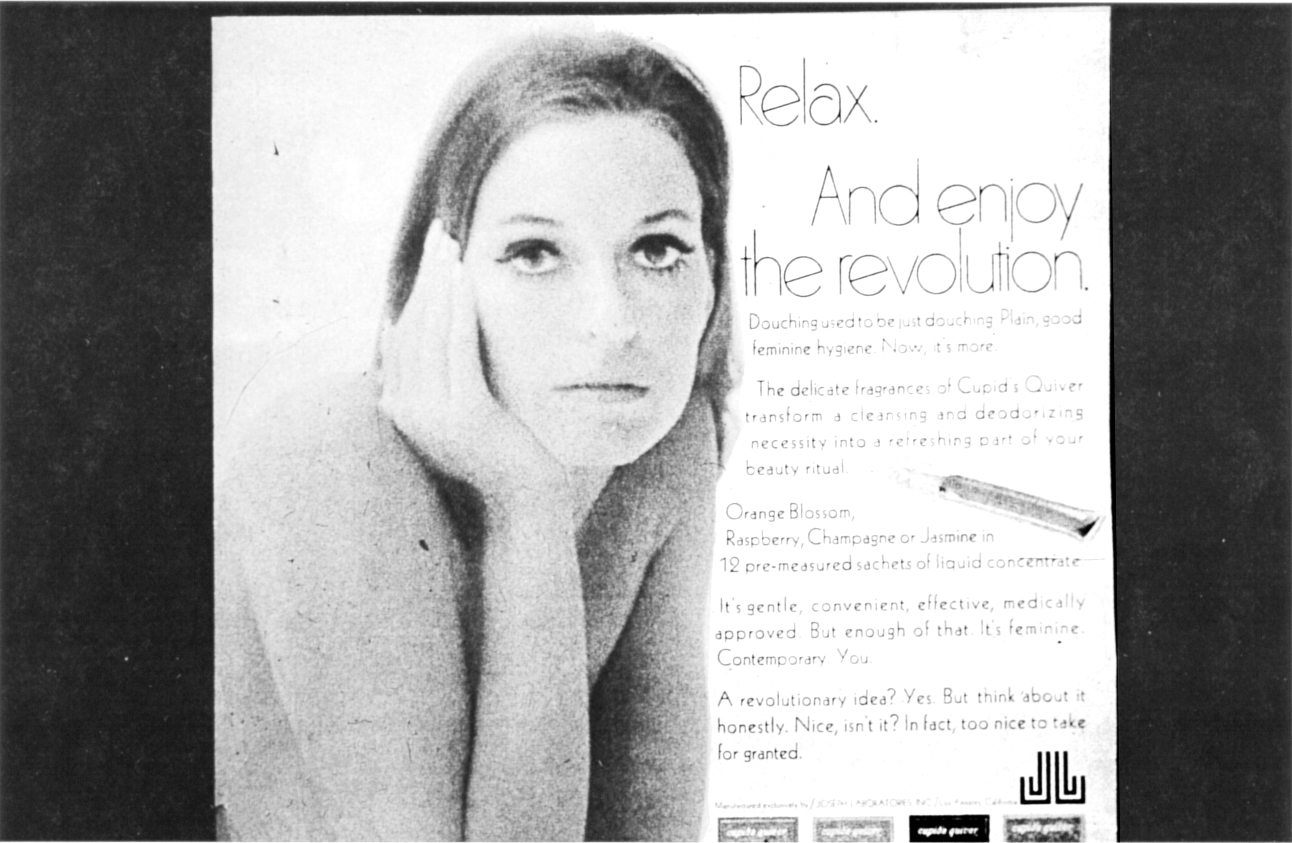

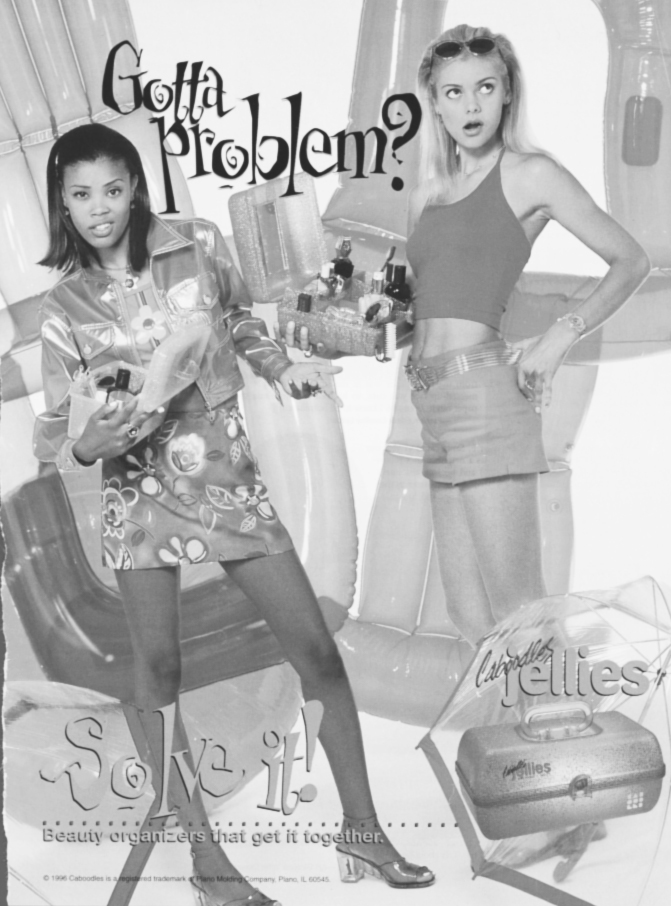

We must constantly perfect and change ourselves, working for self-improvement rather than social change. “Change is a beautiful thing,” says an ad featuring a smiling woman. But the fine print tells us that what we can change is our image, our eye color. “So you’re out to change the world—we can do it together,” said an ad in the 1970s . . . for shoe coloring. Twenty-five years later another ad features two young women, one white, one African-American, both in very trivializing poses. “Gotta problem? Solve it!” says the ad. What’s the ad for? An anti-racism seminar? A consciousness-raising group? No . . . “beauty organizers,” kits for holding cosmetics. The more things change, the more they stay the same. These ads exemplify the way that advertising co-opts any movement for social change and reduces it to the narcissistic pursuit of pleasure and perfection. It has done this most glaringly in the case of the women’s movement. “Relax. And enjoy the revolution,” declared a woman in an ad in the late sixties, inspiring thoughts of women’s liberation. Turns out she was hawking flavored douches. “New Freedom” is a maxipad. “ERA” is a laundry detergent. “Day Care” is a cold medicine. The solution to women being overworked, having a “second shift,” is a new kind of potato . . . or a bath oil . . . or a candy bar. An ad for frozen food says, “For me, freedom comes in a bright red package.” Another ad, which proclaims, “We believe women should be running the country,” turns out to be for expensive sneakers, not political change.

“A woman’s life isn’t always easy on her,” says an ad featuring a woman walking into the kitchen, wearing business clothes, with groceries in her arms and a little child on the floor. What is the ad offering her—child care, more pay, a vacation, a helpful husband? No. The punchline is, “Her laxative should be.” The copy continues, “With all the demands on a woman’s life, it’s no wonder women suffer constipation three times more often than men.”

“Win a year at home with your baby,” declares an ad for a sweepstakes sponsored by an apple juice company, which continues, “Wouldn’t it be wonderful if you could stay at home with your baby for a whole year instead of going off to work?” Women in most other developed nations can count on a year at home with their babies, without having to rely on a lottery. We could too, if we collectively fought for it.

“With Tide, my kid’s clothes have a very bright future,” says a smiling African-American woman hugging her little girl. Of course, unless we deal with racism in our society, the child herself may not have so bright a future.

The wider world of discrimination, poverty, child abuse, and oppression simply doesn’t exist in advertising. There is never the slightest hint that people suffer because of socioeconomic and political situations that could be changed. If we are having difficulty with child care, the solution is to give our children sweets so they will love us, not to lobby for a national child care policy. In the early 1980s an ad campaign for Excedrin used the slogan “Life Got Tougher. We Got Stronger.” In one of these ads, a woman is in distress at her office. The copy says, “Life seems tougher when you’re raising a family and working too.” Indeed it does, but the solution according to this ad is not more equal partnerships in marriage or a national child care policy but simply a stronger aspirin.

Ads such as these have contributed to the myth of superwoman, one of the most damaging stereotypes of all. Young women are encouraged to feel that they effortlessly can combine marriage and a career. Advertising images obscure the fact that the overwhelming majority of women are in low-status, low-paying jobs and are as far removed from superwoman’s elite executive status as the majority of men have always been removed from her male counterpart. In addition, the myth of superwoman places total responsibility for change on the individual woman and exempts men from the responsibilities and rewards of domestic life and child care. It also diverts attention from the political policies that would truly change our lives.

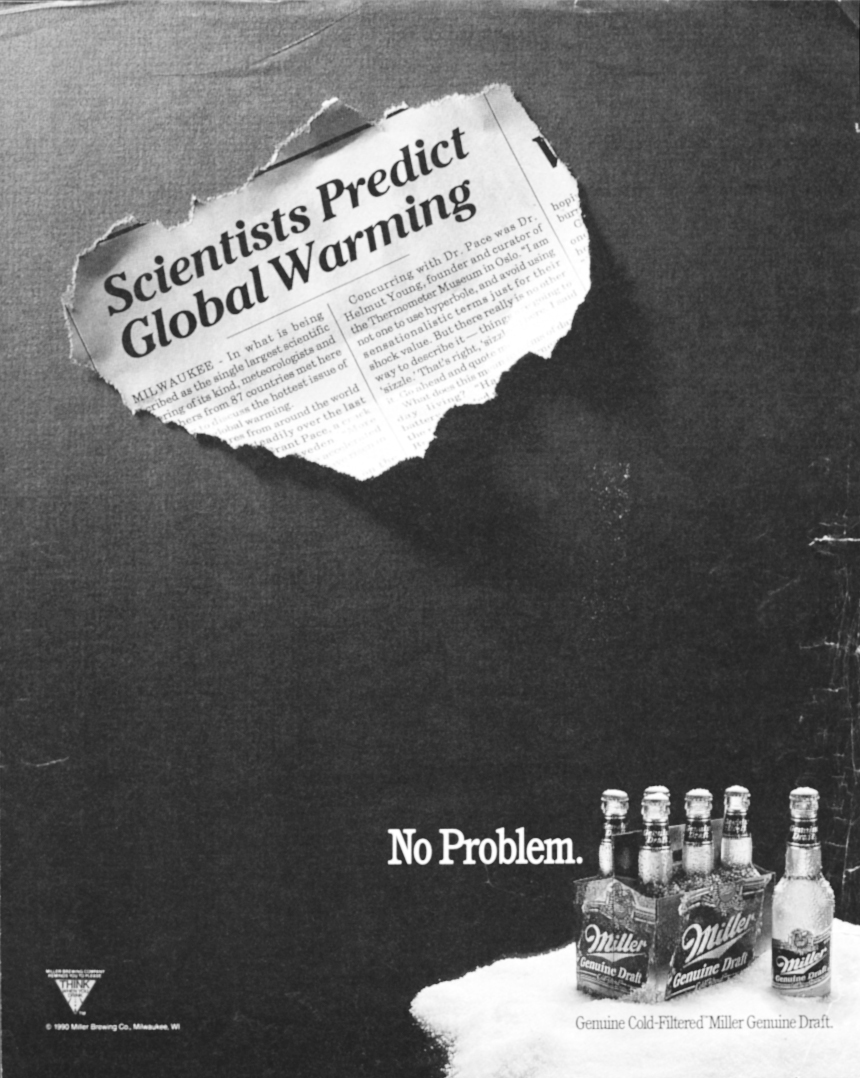

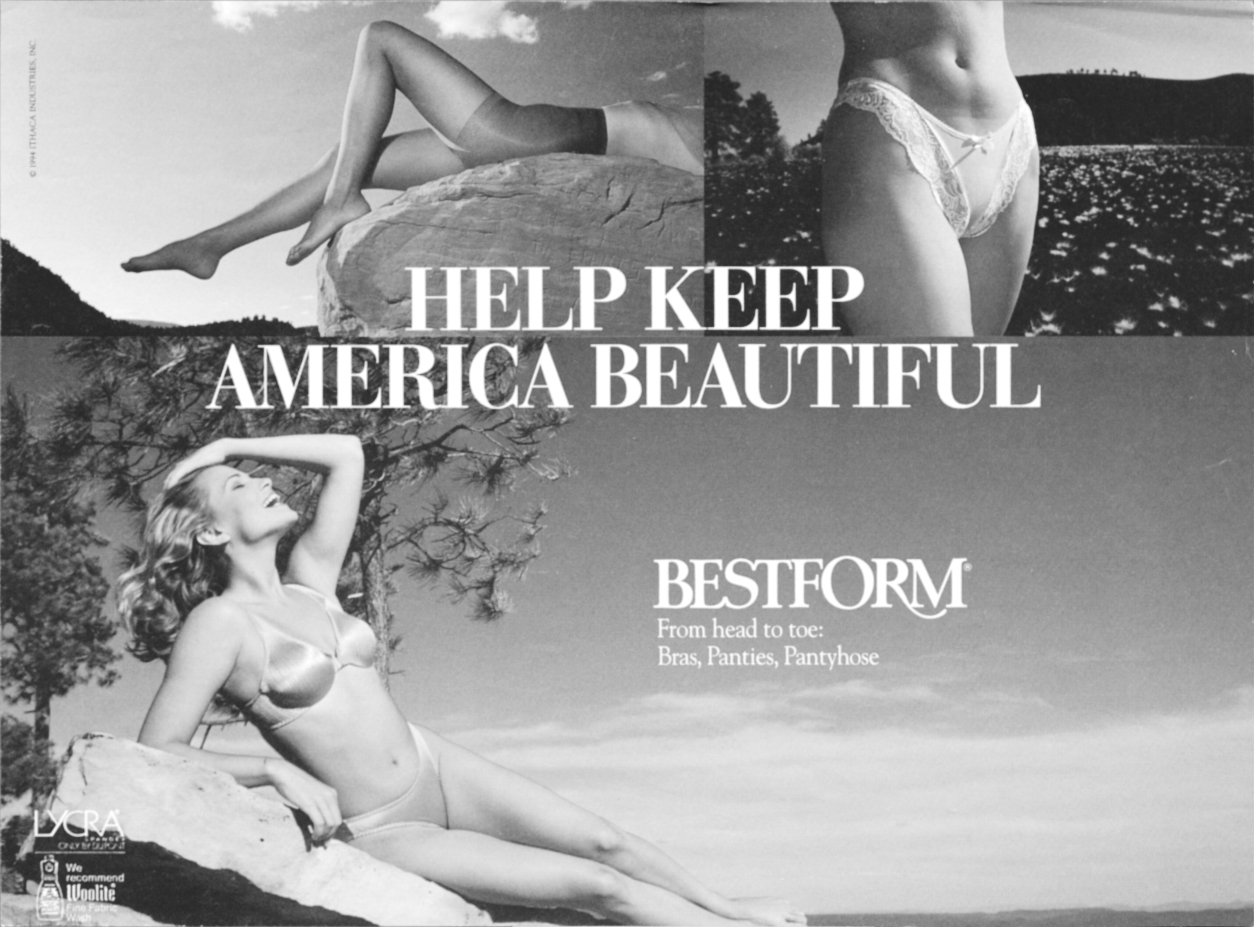

When social problems are mentioned in advertising, it is only to be trivialized and reduced once again to the personal. “Urban decay” is simply the brand name of a cosmetics line. Several ads illustrate advertising’s approach to the threat of environmental destruction. “Scientists predict global warming,” says one ad, which continues, “Miller says no problem.” The icy-cold six-pack of beer in the ad is the obvious solution. “How best to combat global warming?” asks another ad, featuring a young woman in a sleeveless dress. “Something in lightweight wool perhaps.” “You know what’s happening to the ozone,” says an ad for makeup. “Imagine what it’s doing to your skin.” “Help keep America beautiful” is the headline for an ad . . . not about litter but about lingerie, an ad featuring dismembered parts of a woman’s body against scenic backdrops.

One of the most unintentionally hilarious ads I’ve ever seen features an earnest-looking young woman, fashionably dressed in denim, with the copy, “I get really angry when I hear about all the selfish people who are destroying our environment. Polluting the beaches. Burying toxic wastes. Causing acid rain. Someday I want to travel and see the world. I only hope it isn’t all screwed up by then.” What is she selling—the Peace Corps, community volunteerism? No—gold bracelets! This is reminiscent of the notorious Benetton campaign that yokes shocking images of tragedy and misery, such as a dying AIDS patient, drowning Romanian refugees, and the bloody uniform of a dead Croat soldier, with overpriced sweaters.

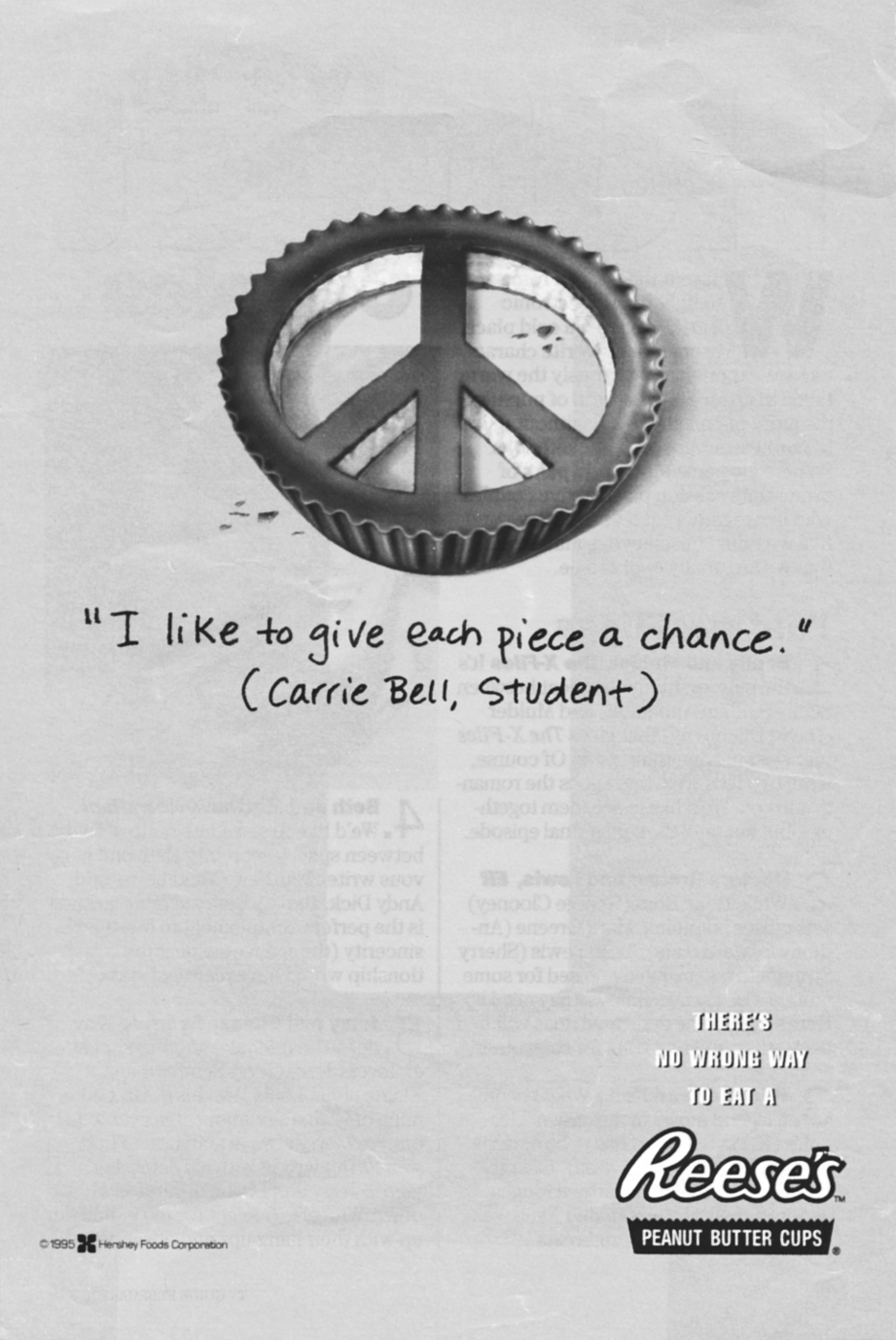

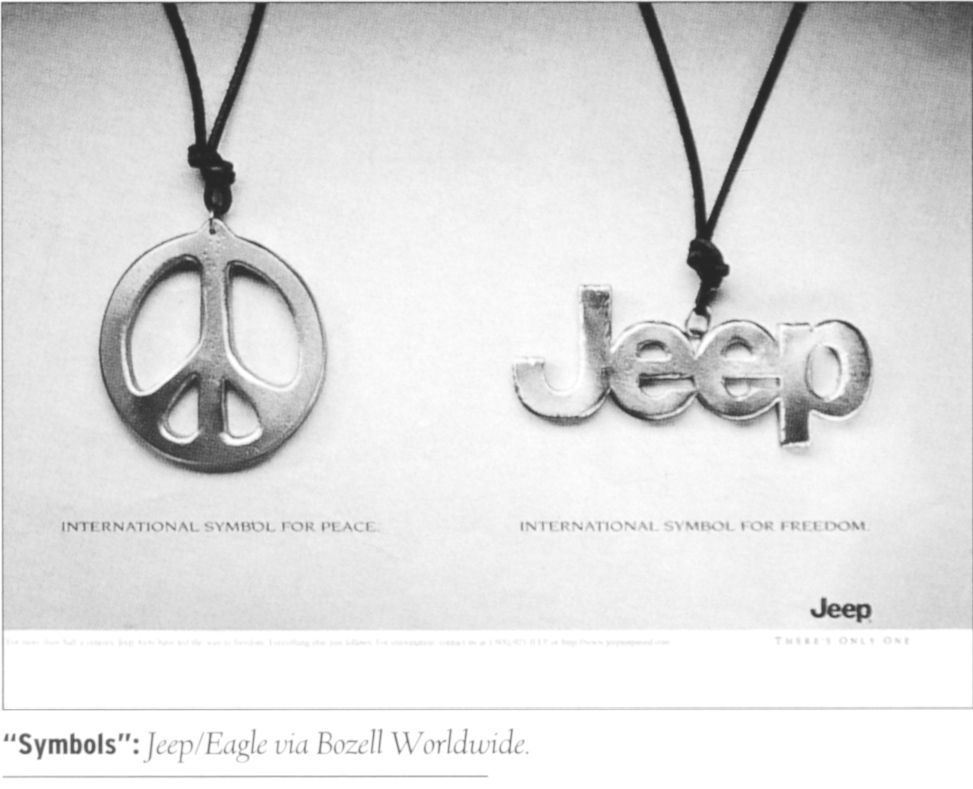

Movements for political change are also trivialized. The peace symbol from the 1960s has shown up in ads for everything from candy to Jeeps. “Give peace a chance” is used again and again to sell spas and vacation getaways, while images of Woodstock are used to sell tampons. “Tampax was there,” says the commercial, undoubtedly true but so what? As Bob Garfield said, so were a lot of things, like shoelaces, rubber bands, and the cold virus. Cynicism about politics shows up in many ads targeting young people, such as one for Wonderbra that offers readers a chance to vote for their favorite model, with the headline “Sure beats voting for president.” A television commercial for Miller beer in election year 1996 shows a young man strolling on a giant political game board, celebrating his right to choose, whether it be candidates or beer. Unctuous politicians spring up in his path, but he chooses a smiling blonde waitress with Lite beer. The commercial ends with bumper stickers bearing slogans such as “Join the party” and “Choose Miller Lite” and the notice that the ad was “Paid for by the Miller Lite Party” Don’t bother voting or trying to change the world—just have another beer. Again and again, everything comes down to the individual and his or her choice of a product. Of course, we can’t expect anything else from advertising. The advertiser’s job is to sell products, not to solve the world’s problems. But the powerful impact of advertising on our culture affects how we conceptualize and approach these problems.

A sea change in the public health approach to alcohol and tobacco problems in recent years has shifted the focus from the indivbidual to the environment. We are learning that many, if not all, of these problems can be reduced by changing the environment. As we see the effectiveness of this approach in dealing with alcohol and tobacco problems, we must widen it to include other addictions and societal problems as well.

Public health experts generally refer to this approach as a “systems” approach, which recognizes that dynamic interactions occur, not only between the individual and the environment, but among various levels of the environment. The individual is viewed as part of a complex social, physical, and political web—family, school, community, workplace, state, and so forth. Changes at one level of the system affect all other parts, so prevention programs must be comprehensive. Single approaches to prevention are bound to be ineffective.

Some absurd examples of the single-minded approach emerged in the wake of the school shootings in Colorado. At least one high school principal banned the wearing of black trenchcoats in his school (because that’s what the killers were wearing), others proposed metal detectors and more armed guards (although there was an armed guard in the Colorado school), and a religious leader recommended posting the Ten Commandments in every classroom (an idea that made its way to Congress). Several people suggested that the problem was not enough guns in schools—if teachers had been armed, they could have taken out the killers. The environmental approach to this tragedy calls for many things—an examination of the socialization of boys in America, the impact of violent video games and other violent media, outreach programs early on to troubled and alienated boys and, of course, gun control. High school has always been hell for misfits but until recently they didn’t have access to guns. Sometimes the people recommending gun control fight with those pointing their fingers at the media, as if there were one reason for this reoccurring catastrophe and everyone must protect his or her turf. The roots are many and the solutions must also be deep and multifaceted.

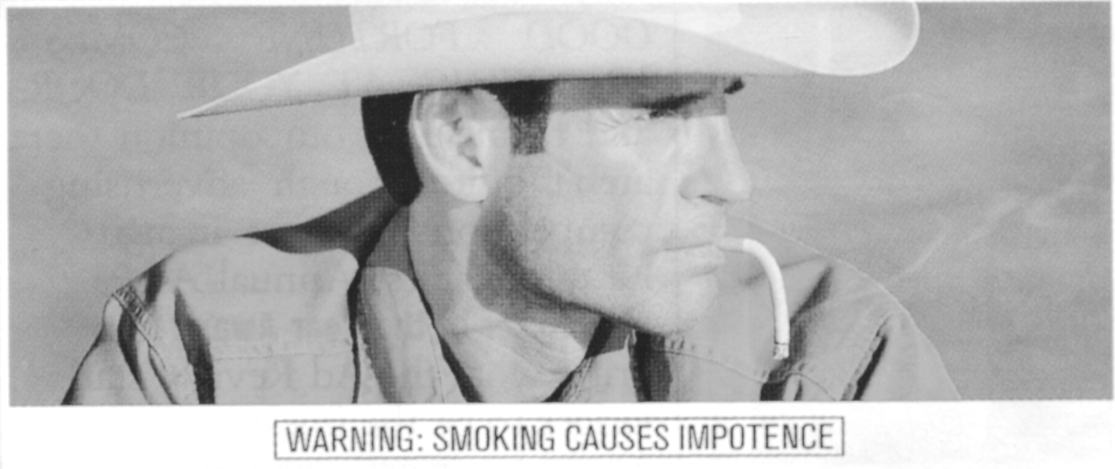

Antismoking organizations used to focus on the individual smoker as the problem and offered health information, pictures of diseased lungs, and advice for quitting. As data showed that this was not the most effective way of improving public health, these organizations switched their strategies to emphasize the role of the environment and the institutional responsibility of the tobacco industry. They fought for a ban on cigarette advertising and promotion, aggressive counteradvertising, much higher taxes and better warning labels, the removal of vending machines, product liability suits, and a crackdown on those who sell cigarettes to minors. With this approach, the focus shifted from individual responsibility to changing public policy.

Does this work? Indeed it does. Since Massachusetts increased taxes on cigarettes and launched an aggressive antitobacco campaign in 1993, consumption of cigarettes has dropped 31 percent, the steepest decline in smoking rates in the nation. In Florida, smoking by middle-school students dropped 19 percent since the state launched an aggressive antitobacco campaign. And several studies have documented that in the 1990s smoking has declined more than twice as fast in California, which has the oldest such program, as nationwide. There have been similar success stories in countries around the world, from Canada to New Zealand. And the norms for cigarette smoking have changed dramatically in the past twenty years.

We can change the norms about alcohol use, dieting, and violence with many of the same measures. To help resolve the problem of high-risk drinking, the individual approach calls for such measures as designated drivers, meaningless slogans such as “Know when to say when” and the oxymoronic “Think when you drink,” and brawnier bouncers at bars. The systems approach calls for higher taxes on alcohol, better warning labels on the bottles and the ads, server training for waitstaff in bars and restaurants, and equal-time provisions for aggressive counteradvertising, among other things. This approach has been adopted by many colleges seeking to reduce the high levels of binge drinking by their students. Some of the strategies include working with local bars and restaurants to curb happy hours and promotions involving cheap booze and publicizing information letting students know that the majority are not binge drinkers, thus diminishing the impact of “imaginary peers.” As a report from the Higher Education Center for Alcohol and Other Drug Prevention says, “Students do not make decisions about the use of alcohol and other drugs entirely on their own, but rather are influenced by campus social norms and expectancies and by policy decisions affecting the availability of alcohol and other drugs on and off campus, the level of enforcement of regulations and laws, and the availability and attractiveness of alcohol-free social and recreational opportunities.”

The alcohol and tobacco industries do not like the systems approach not only because it works to reduce consumption (and therefore their profits) but also because it undermines their marketing messages and reduces the attractiveness of their products, especially to young people, whereas their little slogans emphasizing individual responsibility are designed to have no effect. In general, if we want to know what will really work to solve these problems, we should look at what the industries are fighting hardest against. The alcohol industry loves the designated driver campaign, which has no effect on consumption, but lobbies hard against increased taxes or any restrictions on advertising. Most industries want the focus to stay on the individual, because a focus on the environment inevitably leads to corporate accountability and restrictions. As the gun industry loves to say, “Guns don’t kill people. People do.” When Ralph Nader first spoke up about the role of unsafe cars in automobile crashes, the automobile industry immediately attacked him and responded with a campaign stating that only the individual driver is responsible: Their slogan was “It’s the nut behind the wheel.” We’ve known for a long time, of course, that Nader was right.

The systems approach is easily misunderstood because some of the interventions can seem trivial, especially in light of the extent of the problems. When some parents in a Boston suburb complained about an advertisement for beer in a Little League field, a well-known Boston columnist ridiculed them as “touchy-feely, politically correct busybodies” who thought the ad would immediately “turn their kids into drunks.” He concluded, “It’s a bad sign when adults figure their own kids are such weak little simpletons that they might commit an error based on a billboard when any sane liberal knows: Ads don’t drink. People do.” Like a lot of people, he completely missed the point, which is that we give a message to our children about the normalcy of beer-drinking and about societal expectations when we allow such an ad on a Little League field. A single ad—or scores of ads—won’t turn kids into drunks, but they are part of a climate that normalizes and glamorizes drinking, and research proves that this especially affects young people.

There has been a great deal of publicity in recent years about alcohol and cigarette campaigns that have targeted African-Americans (for example, Uptown cigarettes and Powermaster malt liquor) and children (for example, the Joe Camel campaign). There should be similar widespread publicity about the diet ads and the ads featuring risky attitudes about eating. Eating disorders must also be treated as a dysfunction of the culture, not just of the individual.

If we were to combat the obsession with thinness from a public health perspective, what would we do? We would demand that Congress, the Federal Trade Commission, and the Food and Drug Administration take an active role in investigating and regulating diet programs and products. We would put warning labels on the ads and demand that the ads include the success rate (it is important for consumers to know that 95 percent of all diets fail). I sometimes fantasize putting warning labels on ads featuring very thin models as well—“Warning: Attempting to achieve this look can ruin your life.” We would have prevention programs starting in elementary school, as we do for alcohol and other drugs. But we must also be sure, via scientific evaluation, that these programs are effective. A lot of money has been wasted on prevention programs that are useless at best and sometimes harmful (such as programs that are more likely to teach kids how to use drugs or practice bulimia than to prevent anything).

Therapists, many of whom have moved to a great extent in recent years from an individual to a familial approach, must take the cultural context into consideration too. Just as they can’t successfully treat lesbians or gay men or people of color without taking homophobia and racism into account, they can’t treat anyone without taking sexism into account. They certainly can’t treat young women with eating disorders without considering an environment that demonizes large women and rewards those who starve themselves. They can’t treat depression without considering addiction, and they can’t treat female addicts without understanding male violence and sexual abuse. Family therapists must recognize that marriages fall apart because of individual failures, to be sure, but also because they exist in a culture that is hostile to marriage, commitment, delayed gratification, and families. We are always responsible as adult individuals for our choices and actions, but our cultural environment makes it exceedingly difficult to raise healthy children, to have successful marriages, to avoid addiction, and to have nonmaterialistic values.

We can learn a great deal from the public policy advocates who have been battling the alcohol and tobacco industries for the past several years, with some striking success. Knowing that statistics can often be numbing and meaningless, they have developed strategies to bring them to life and to capture the attention of the media and the public. For example, when Perrier withdrew its product from the shelves because some of it was tainted with benzene, the antismoking activists pointed out that it would take thirty-three bottles of tainted Perrier to equal the benzene in just one pack of cigarettes. They held a press conference with the thirty-three bottles of Perrier lined up behind them. We need to be equally creative in dramatizing the damage that the obsession with thinness, for example, is doing to women and girls.

We must adopt a similar public health approach to other social problems, such as rape and violence against women and the sexual abuse of children. Former U.S. surgeon generals Antonia Novello and C. Everett Koop, who spoke out bravely about alcohol and tobacco, have also spoken out about violence against women as a public health issue. We should encourage other public health leaders to become involved with these issues. These are all major public health problems that endanger the lives of women and girls, indeed that cut to the very heart of women’s energy, power, and self-esteem.

Child abuse is perhaps the most important public health issue. It is terrible in and of itself and it is also at the root of many other societal problems, from addiction to violent crime to domestic violence. Our current approach to child abuse is haphazard, chaotic, and underfunded. As with all public health problems, we need an emphasis on prevention. We should teach parenting skills and basic child psychology in our schools (and have the courses be at least as important as driver’s ed!). Studies in Tennessee and New York find that home visits by nurses following the birth of a child reduce subsequent health problems in both the mother and the child and also reduce child abuse and neglect, criminal behavior, and the use of welfare. It costs a great deal less to have a team of people help stressed young parents learn about parenting than it does to intervene when the child has already been damaged. Many states are moving toward a team approach to child abuse, each team consisting of a pediatrician, a nurse, a psychologist, a social worker, and a law enforcement expert. I would like to see these teams on the scene before children are abused—they could get involved immediately with high-risk families. Everyone on the team should be knowledgeable about addiction, since it is a factor in the majority of cases of child abuse. Indeed all gatekeepers—teachers, doctors, law enforcement people, clergy, psychologists—should be truly educated about addiction and look for it automatically wherever there is trouble. Assume addiction until one discovers otherwise.

A systems approach to child abuse would also recognize the link between poverty, unemployment, neighborhood deterioration, and lack of economic opportunity and all kinds of domestic violence. Community-level interventions that reduce parental stress, such as flexible work schedules, adequate child care services, and parent support groups, are important prevention strategies that work on an environmental level rather than focusing exclusively on high-risk families.

Among many powerful tools that can change the environment is counteradvertising—advertising that gives us honest information and advertising that deglamorizes products such as alcohol and tobacco. Contrary to what Audre Lorde said, sometimes the master’s tools can dismantle the master’s house. I had a wonderful experience working with young advertisers in Boston preparing the Tobacco Control Program counteradvertising campaign. Many people in advertising are creative and smart and thrilled to be able to use their skills in a positive way. Counteradvertising should be mandated through the fairiness doctrine for electronic media and paid for by alcohol and tobacco taxes.

Counteradvertising is very different from campaigns that target individuals (such as ads that recommend quitting smoking or not driving while drunk). True counteradvertising takes on the industries. As one California ad said, “Warning: The tobacco industry is not your friend.” Another in this campaign features two cowboys riding into the sunset with the headline, “I miss my lung, Bob.” Parodies of popular ads, such as the Absolut ads that run in Adbusters, are very effective. Kalle Lasn, editor of Adbusters, calls this use of parody and satire against ads “culture-jamming.” Young people generally love designing ads like this, so it is not difficult to get them involved in campaigns and contests.

Another extremely important aspect of breaking through the climate of denial is to teach media literacy in our schools, starting in kindergarten. The United States is one of the few developed nations in the world that does not teach media literacy, but a growing national movement is trying to change that. We all need to be educated to become critical viewers of the media. Without this education, we are indeed sitting ducks. We also need to insist that our schools be Ad-Free Zones.

In recent years, there has been increasing understanding of the relationship of media literacy to substance abuse, violence, and other societal problems. A program called Flashpoint teaches media literacy to adolescents in the juvenile justice system. The American Academy of Pediatrics offers a course called Media Matters to all its members and urges them to do a media history along with a health history with every patient. Scores of other organizations and groups are incorporating media education into their agendas. Huge and powerful industries—alcohol, tobacco, junk food, diet, guns—depend upon a media-illiterate population. Indeed, they depend upon a population that is disempowered and addicted. They fight our efforts with all their mighty resources. And we fight back, using the tools of media education that enable us to understand, analyze, interpret, to expose hidden agendas and manipulation, to bring about constructive change, and to further positive aspects of the media.

As parents, we can help our children to become media-literate, both by fighting for media literacy programs in our schools and by talking with them about the media. We should watch television with our children, choosing programs with care. My daughter and I look at the television schedule every week and select a few programs to tape. We then watch them together, usually skipping through the commercials. We should listen to our children’s music, being careful never to condemn the media they love or blame them for loving it. We should pay attention to it and help our children and ourselves to be more critical viewers and listeners. About the only autocratic thing I do with my daughter is to forbid her to wear clothing that advertises a store or a product (and, of course, I don’t wear such things myself). I also try not to buy anything for either of us that is advertised on television. When she was young, this eliminated many problems, since almost everything that is advertised on television for children is unhealthy and unimaginative. The food is terrible for them, the toys stupid, sexist, and disappointing.

We can limit our own consumption and television-watching and both encourage and engage in other activities, such as reading, sports, drama, volunteerism, environmentalism. We can also start small discussion groups with our children (beginning when they are young enough to be thrilled by the idea!). When my daughter was ten, I started a mother-daughter group with several of her best friends and their mothers. We meet monthly and talk about a variety of issues, such as homework, dating, clothes, money, food, and the media. I think we all enjoy the mutual support, the openness, and the close connection. And, of course, we can model citizen activism for our children as we work to improve the cultural environment in our communities and throughout the nation and world.

In addition to the media literacy movement, another movement that is gathering steam is what is sometimes called the “voluntary simplicity” movement. This consists of many diverse groups and organizations trying to reduce consumption in general, not only to save the earth but also to save our souls. Many of these organizations, as well as public health and media literacy organizations, are listed on the resource list on my Website (www.jeankilbourne.com). They all have abundant ideas for action, far more than I could possibly include in this chapter.

The systems approach to public health problems is inherently political. The individual approach doesn’t rock the boat—it basically says that the world is fine, the environment is fine, but you, the individual, must shape up, resist temptation, stop being so weak-willed. An environmental approach questions the nature of the world—and inevitably confronts the corporations that depend on addiction for profit. For this reason, it has been very difficult to get the government, increasingly dependent on donations from big business, to use this approach. It is also almost impossible to shift the focus from the individual to the environment without “offending the sponsor,” which explains the general reluctance of the media to adopt this perspective. By now, many people no longer have the attention span necessary to track an issue for a long time. They can follow O. J. Simpson’s trial, but would never stay tuned for a year-long discussion of the roots of domestic violence and the public policy measures necessary to curb it.

As large, diversified corporations merge to create media dynasties, it becomes more and more difficult to get accurate information about anything. Perhaps most insidiously, it becomes difficult to get information about the media conglomerates themselves. There was a virtual news blockade on information concerning the Telecommunications Act of 1996, a bill that effectively threw open the doors to media monopolies. Neither the passage nor the signing of the most sweeping telecommunications legislation in sixty years made the top-ten stories in their respective weeks. The media are now almost completely under corporate control and corporate interests structure almost every message we get. Truly alternative perspectives have vanished. Of course, we must support alternative media, but we must also fight to take back the public airways (that belong to us, after all) and to insist on access and diversity.

It is not surprising that criticism of this situation rarely makes it into the mass media. Indeed corporate criticism in general is seldom allowed. Challenging the culture of commercialism is especially taboo. The Vancouver-based Media Foundation has been trying for years, without success, to get some of its anticonsumerism advertisements into the mass media. According to the foundation, a television spokesman said, “We don’t want the business. We don’t want any advertising that’s inimical to our legitimate business interests.” As prize-winning reporter Bill Lazarus says, “When you write about government, the attitude of [editors] tends to be ‘no holds barred.’ When you write about business, the attitude tends to be one of caution. And for businesses who happen to be advertisers, the caution turns frequently to timidity.”

No wonder there is very little mainstream media coverage of serious, chronic, and pervasive abuses of corporate power. Health coverage almost always focuses on personal health habits, on exercise and weight control, for example, rather than on problems such as toxins in the environment, put there by corporations that underwrite public broadcasting and advertise in the media. Endless blame is heaped on welfare mothers but corporate welfare, such as the savings and loan bailout, which costs the taxpayers far more, is barely mentioned. The news brings us a daily litany of crimes committed by individuals but rarely anything about corporate crime, although far more people will die because of inadequate health insurance, faulty products, or toxic waste than from serial killers. Mass murderers have nothing on tobacco industry executives, yet the executives get away with committing perjury before Congress. Each year sixty thousand workers die from workplace injuries and diseases, almost three times the number of people “murdered,” yet we hear litle about that. Thus, the role of corporations in major problems of our times is erased and, in this Information Age, people are literally dying from lack of information.

Democracy itself is endangered when information is given to foster private economic gain rather than to educate and enlighten the public so it can make intelligent decisions. As Studs Terkel said, “If journalists cannot freely report the news which disturbs the wealthy and the powerful, then we’ll learn only what the big boys want us to learn.” These days the big boys don’t want us to learn much more than what brands to buy (of politicians as well as of beer and cars).

Politicians are examined with a microscope by the media and are assumed to be corrupt (as indeed they sometimes are), but the men who control the conglomerates are usually invisible. Thus, it is fashionable to hate the government, to be cynical and apathetic about politics, and yet to remain completely ignorant about the people who have even more influence on our lives. In recent years there has been almost complete alienation of the citizenry from its government. In 1966, 58 percent of incoming college freshmen said keeping up with political affairs is “very important.” In 1998, only 27 percent agreed. A profound distrust of government is encouraged by the big corporations because it is in their interest. After all, it is only the government that can regulate them. We need enlightened government now more than ever, both to protect us from corporate control and to pursue progressive public policies. Public policy won’t change until ordinary citizens hold elected officials accountable for their votes.

Although advertising tries to convince us that freedom is our right to buy things and democracy our ability to choose from a variety of consumer goods, most of us know better. We know that democracy requires active participation from an informed citizenry. Journalistic integrity is crucial to democracy, as is an aware and skeptical public audience. We have a cynical audience, an audience so apathetic that most people don’t even bother to vote (more people watched the Superbowl than voted in the 1996 presidential election), but we certainly don’t have an educated and informed audience. According to the funder of a 1998 national report on the state of U.S. civil life, “Corrosive cynicism has crippled our civic spirit, and a sense of helplessness has sapped our civic strength.” When people are working hard to earn money to buy a lot of stuff and then spending their free time shopping, it’s hard to get involved in community issues or civic affairs—especially if they believe that nothing they do will make any difference anyway.

Ever since Ronald Reagan’s reign, big business’s political allies have been pushing a sweeping deregulatory agenda, unraveling some of the few public controls we have left as “watchdogs” over corporate abuses. This burgeoning corporate power threatens the very core of our democracy, and it poses a growing threat to human health and the environment. We have much more to fear these days from corporate giantism than from big government, but it is very difficult to get people to understand this. Most Americans define freedom very narrowly as freedom from government, as if nothing else could pose a threat. And George Soros, one of the most successful capitalists in history, says, “Although I have made a fortune in the financial markets, I now fear that the untrammeled intensification of laissez-faire capitalism and the spread of market values into all areas of life is endangering our open and democratic society. The main enemy of the open society, I believe, is no longer the communist but the capitalist threat.”

It is the increasingly important role of advertising in political elections that necessitates huge campaign coffers, which in turn makes politicians dependent on corporations. Most of the half-billion dollars spent during the 1996 presidential election came from American corporations and Wall Street. As these giants become global, the campaign money increasingly comes from everywhere around the globe—and, of course, with strings attached. Campaign finance reform might well be the most important issue of our time, but it is hard to put a sexy spin on it—it won’t sell a lot of newspapers or draw huge television audiences. It also isn’t in the interest of newspaper and television owners who reap huge sums from political advertising and contribute mightily to politicians themselves. As Richard Goodwin says, the issue is “not about how politicians should be financed, but how America should be governed, not about how we elect officials, but how they rule the nation. . . . Under the deceptive cloak of campaign contributions, access, and influence, votes and amendments are bought and sold.” One obvious solution to this problem is to ban political advertising or at least to limit it to head shots of the candidates talking about their beliefs and policies. No music, no fancy images, no attack ads, no gimmicks. We could also put a cap on what politicians can spend on elections and resurrect the fairness doctrine, so that every commercial would trigger a free response.

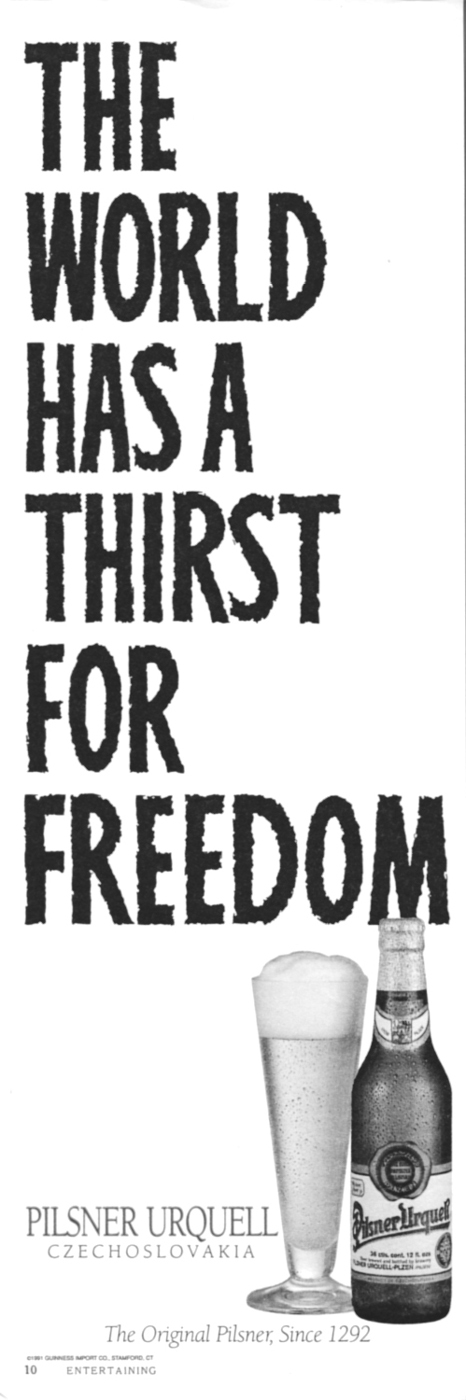

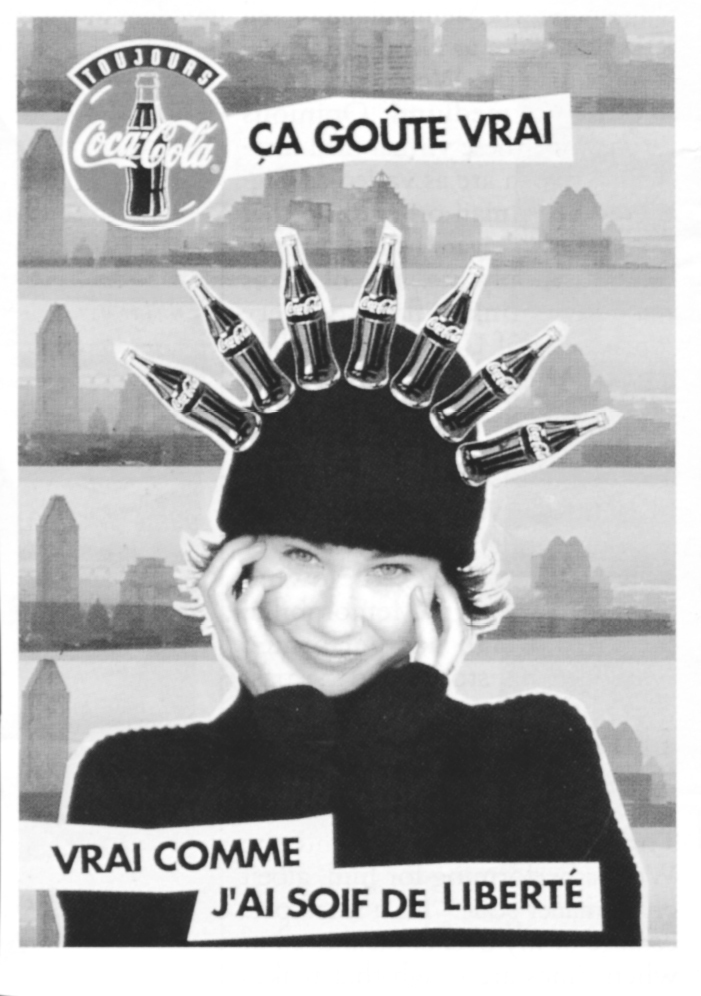

We must also reclaim and redefine the concepts of freedom and rebellion that have been so distorted and co-opted by advertisers. They spend billions of dollars a year trying to convince us that we can buy freedom—most ironically, that we can buy freedom via the purchase of addictive products. “The world has a thirst for freedom,” says an ad for an imported beer, while in another ad, the end of the Cold War is reduced to “Freedom of vodka.” To paraphrase Kris Kristofferson, freedom’s just another word for something else to buy. “It’s not just fashion, it’s freedom,” says an ad for wool. “A declaration of independence” is a statement about perfume, and nail polish “sets you free in 90 seconds!” A bus shelter poster in Montreal features a young woman representing the Statue of Liberty, but with a crown composed of Coca-Cola bottles—“It tastes real,” says the ad, “as real as I thirst for freedom.” “Not since the fork-in-the-road sign, has the world been witness to such a pure example of choice,” proclaims an ad for Diet Snapple drinks. Consumption becomes a substitute for democracy, with the choice of what to eat or wear or drink taking the place of meaningful political choice. People all around the world are being told that the way to experience American individualism and success is to smoke Marlboros and drink Budweiser. We must never forget that this is a global issue.

Young people are especially targeted because advertisers know that freedom and rebellion are of great importance to them. So they put smokers on the Statue of Liberty to sell cigarettes, Phillip Morris buys the rights to our Bill of Rights, the diet industry offers “the taste of freedom,” and Calvin Klein and his ilk surround us with messages lauding casual, uncommitted sex and pornography as freedom of expression. Be free, be a rebel . . . be addicted, be a consumer! A lot of children and young people fall for this propaganda. Desperate to be unique in a conformist culture, they follow the crowd right over the cliff—drinking, smoking, engaging in dangerous sex, compulsively shopping for recreation, stuffing and starving themselves. O brave new world, where Addiction is Freedom and Conformity is Rebellion.

Those who resist this message are labeled “antifreedom.” If we protest the targeting of children by the tobacco industry, we are called “lifestyle police” and “public health Nazis.” If we suggest that popsicles containing alcohol and beer commercials using talking frogs are inappropriate, we are called “neo-Prohibitionists” and “Carrie Nations.” If we complain about Calvin Klein’s appropriation of child pornography in his ads, we are “the nation’s nannies,” antisexual prudes, in bed (so to speak) with the Christian right. If we protest the casual sex, the violence, the consumerism, we are part of a Big Brother government trying to tell everyone what to do. The alcohol industry, the tobacco industry, the junk food industry all have billions of dollars with which to frame the debate in this way and they are very successful. In 1999 a bill before Congress designed to prevent children from starting to smoke was defeated after the tobacco industry spent $40 million on advertising framing the issue as big government versus freedom-loving individuals.

One of the most disturbing displays of corporate power in recent years has been the hijacking of the First Amendment. Philip Morris did this quite literally by buying the right to use the Bill of Rights in an advertising campaign. But, on a more subtle level, as giant corporations spend billions of dollars on public relations and systematically construct their images, they have increasingly become the citizens whose rights need protecting, while the rest of us are merely consumers. Since many Americans are ardently and correctly concerned with protecting the First Amendment, it has been easy for corporations to get us to confuse our rights with their rights. Eminent legal scholars not tied to the alcohol and tobacco industries conclude that reasonable regulations on alcohol and tobacco advertising that do not unduly restrict adults from obtaining accurate information about the availability of these products (for example, price advertising and accurate advertising in adult-oriented media) do not violate the First Amendment.

The truth is that the First Amendment was not meant to protect commercial free speech and that commercial free speech today is often the enemy of private speech. What chance do grass-roots public health groups have against the huge assets and political power of the tobacco, alcohol, junk food, diet, and other such industries? How can someone be elected to office who can’t afford advertising to counter the mudslinging of special interest groups? How can speech be considered free when television routinely excludes unusual or extreme or even merely progressive points of view from the news and political programs? How can individuals speak out about food safety if they risk being sued by the food industry, as Oprah Winfrey was by the Texas cattlemen? She won, but had to spend almost a million dollars on her defense. As Max Frankel says, this “relatively recent reading of the Constitution produces a false equality between a corporate shout and every ordinary citizen’s whisper.” Corporate wealth monopolizes debate, corrupts politicians, and dictates policy. Increasingly, the First Amendment is being used as a shield to protect the wealthy and the powerful, such as tobacco advertisers and pornographers.

It is time for us to fight back, to resist this name-calling and to redefine freedom, liberation, and rebellion in our own terms. We can turn these advertising messages inside out. We are free when we are not addicted, when we can be our real selves, when we are as healthy as possible in body and soul, when we are authentically sexual (which means loving and treasuring our imperfect bodies, as well as each other). We are rebels with a cause when we take on these industries and their destructive advertising messages. We can and must unhook ourselves from the lure, the bait of advertising.

We need connection—not the illusion of connection provided by advertising, but real connection—in our private lives and in our public policy. These days our public policies often reflect our evasion of connection and of committed relationships—our short-term solutions, our abandonment of the poor, disabled, and mentally ill, our refusal to provide basic health care for everyone, even children, our dismissal of workers’ rights, and our eagerness to imprison and execute people when they are adolescents or adults as opposed to investing in programs that would help them while they are children and babies. At a time when we desperately need to encourage people to care for each other, to restore a sense of communal life, we often seem to be doing exactly the opposite.

As parents, the most important thing we can do for our children is to connect deeply and honestly with them. A two-year study of over twelve thousand adolescents reported on in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that the best predictor of health and the strongest deterrent to high-risk behavior in teens was a strong connection with at least one adult, at home or at school. This finding held up regardless of family structure, income, race, education, amount of time spent together, where or with whom the child lives, or whether one or both parents work. The message is clear: Good relationships create the resilience that prevents dangerous, acting-out behaviors in our children.

Of course, we also need to work politically to create the kind of culture that makes it easier to have successful relationships with our children. Sylvia Ann Hewlett and Cornel West, who have formed a parenting movement called the National Parenting Association, argue that “at the root of the assault on families is the triumph of a marketing culture which promotes hedonistic, narcissistic, and individualistic ways of being in the world. These ways of being make it harder for anyone to support or to honor non-market activity, of which parenting is a primary example. . . . Compassion and conscience are constructed through the child-parent relationship.” We must recognize that many children don’t have the possibility of a strong connection with a parent, so we must make sure they get these connections elsewhere. We must support youth centers and organizations, good schools, mentoring programs, and programs to identify children of addicts and other children at risk.

We must cherish all children, not just our own. The emphasis on “parental responsiblity” overlooks the fact that millions of children have absent, addicted, crazy, and irresponsible parents—parents driven so mad by their own childhoods that they blindly perpetuate the legacy of abuse, addiction, violence, and destruction. Maybe it’s too late to save most of these parents, but it’s not too late to save their children and thus in turn their children’s children.

We can’t have good relationships with our children or anyone else if we are addicted. So we must have the courage to kick our addictions, no matter what form they take. Isolation is at the core of addiction and connection is what heals us. Both advertising and addiction lead us into narcissism, and recovery is possible only if we move away from this self-obsessed focus. The brilliance of Alcoholics Anonymous (and other programs modeled on it) is the recognition of this fact. Addicts recover by helping other addicts. Self-help is completely the wrong term for what goes on in these groups. As Margaret Bullitt-Jonas says about recovering from an eating disorder, “It is fear that drove me into recovery, but it is love that keeps me there.”

We need to come together and speak out about our addictions, our abuse, our recovery. We will discover, as women did in consciousness-raising groups years ago, that we are not alone. There is and will continue to be a backlash that will label us “whiners” or “victims” if we speak out in this way (and indeed there have been some whiners on the scene). We do not consider ourselves victims, but most of us were indeed victimized as children and we want to prevent today’s children from being similarly victimized. We are survivors, we are legion, and we will share our experience, strength, and hope with each other.

As Jill Nelson says, “I have learned to control and use my rage because if I don’t, it will control and use me. This is why I gave up those things I once used to stifle my rage, the liquor and drugs and late-night fats and disembodied sex—universal vices, escape routes women often take to deaden the pain, repress our frustration, suppress those niggerbitchfits. Turning my rage outward, I have not committed homicide or suicide because the flip side of my rage is my conviction that change is possible, that communication is key. I have learned that the only thing to do with my rage is recognize it, temper it with love, and blend the two together into hopeful action.”

Of course, it is not just addicts who need healing. Heart specialist Dean Ornish instructs his patients to do acts of kindness for one another. He has written, “Anything that leads to real intimacy and feelings of connection can be healing in the real sense of the word: to bring together, to make whole.”

We need coalitions, networks, conferences, public outcries. We need all kinds of people coming together—in our communities, in our schools, in our places of work and our places of worship. We need what George Gerbner calls, and has founded: a Cultural Environment Movement. We need parents, educators, pediatricians, business people, psychologists, the clergy—everyone speaking out and saying, as anchor man Howard Beale so memorably did in Paddy Chayevsky’s Network, “I’m as mad as hell and I’m not going to take it any more!” Our survival is at stake. We literally cannot go on like this—we will destroy the planet. We must rise up, break through the denial, and act to save ourselves, our children, and future generations.

I once heard a parable about a wise old woman who lived in a village. A boy in the village decided to trick her. He trapped a small bird and told his friends that he would take it to the woman and ask her if it were dead or alive. “If she says it is dead, I will release it,” he said, “and if she says it is alive, I will crush it to death.” The children went to the old woman and the boy said, “I have a bird in my hands. Is it dead or alive?” The old woman looked at him and replied, “It is in your hands.”