Chapter 22

The Basics of Private-Label MBS

Things are not always as they seem; the first appearance deceives many.

Phaedrus 444–393 BC

Private-label or nonagency MBS are mortgage-backed securities issued without the guarantee of Fannie Mae, Freddie MAC, or Ginnie Mae. To achieve the credit ratings that are assigned to each class or tranche and to protect the investor from losses, private-label MBS (PLMBS) rely on internal credit enhancement. Typically, this enhancement employs a combination of the following:

- Excess spread, the difference between the interest paid to the liabilities (notes issued) and the interest earned on the assets (mortgage loans)

- Overcollateralization (OC), the difference between the principal amount of the notes issued and the principal amount of the underlying collateral

- Subordination, bonds subordinated in priority of principal repayment

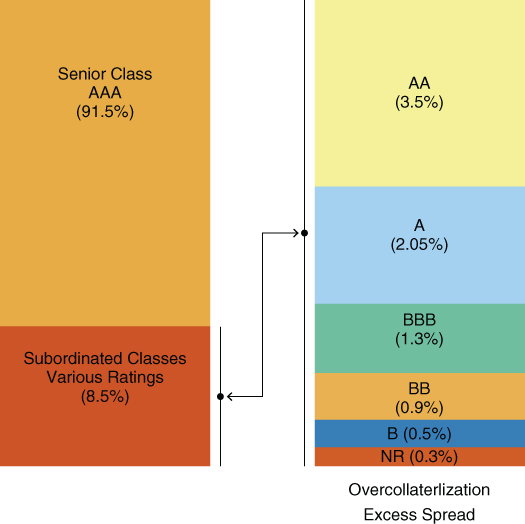

Losses due to defaults are absorbed in reverse priority through the capital structure (Figure 22.1) first by excess spread, then by write-down of the overcollateralization (OC) account, and finally via the principal write-down of the subordinated bonds.

Figure 22.1 Prime MBS Credit Enhancement at Deal Inception

The collateral used in a private-label transaction may consist of either fixed-rate collateral, adjustable-rate collateral, or a mixture of both. In order to accommodate the different groups of collateral used in a transaction several credit enhancement structures have been designed. These structures are known as I, H, or Y structures.

22.1 I Structure

The type I credit enhancement structure (Figure 22.1) accommodates a single collateral group of either fixed-rate, adjustable-rate, or mixed loan types. Although the issuer may mix loan types in an I structure, normal practice implies a single loan type that is either fixedrate or adjustable rate. The benefit of the I structure is largely the absence of cross collateral credit enhancement, which serves as a credit subsidy between collateral groups.

22.2 H Structure

The H structure (Figure 22.2) can be thought of as a group of distinct transactions, with the exception that the excess interest between each of the collateral groups is shared in order to maintain the targeted overcollateralization of each group. The H structure is often referred to as a crosscollateralized transaction, since the credit support is subsidized between between collateral groups via the redirection of excess interest.

Figure 22.2 H Credit Enhancement Structure

Consider the following scenario. Group 1's excess interest is insufficient to cover losses and maintain the collateral group's target OC level. However, group 2 excess interest is sufficient to cover its losses and maintain its target OC level. In this case, the remainder of group 2's excess interest after absorbing losses, if any, is used to bring group 1's OC to its target level.

22.3 Y Structure

The Y structure also allows for two distinct collateral groups and takes its name from the fact that the diagram of the credit enhancement of the structure resembles the letter “Y.” Unlike the H structure, the Y structure employs a single subordination scheme to support the senior classes of both groups 1 and 2. Due to the co-mingling of the assets that fall below the AAA rating level, the Y structure, like the H structure, subsidizes losses between both collateral groups.

Figures 22.1 though 22.3 present the structures used to achieve a AAA credit rating across the nonagency (private-label) MBS sector. The most direct structure (the I structure) subordinates losses of a single collateral group. Both the H and Y structures allow for each collateral group to subsidize the losses of another. A transaction allowing for the subsidy of losses between collateral groups complicates the credit analysis of private-label MBS. The complexity arises due to the fact that the investor must analyze the credit of all collateral groups and determine the extent to which one collateral group may subsidize the other.

Figure 22.3 Y Credit Enhancement Structure

For example, consider an H structure consisting of a fixed-rate collateral group (1) and an adjustable-rate collateral group (2). To the extent that losses are greater in group 2 and excess interest from group 1 is reallocated to build OC in group 2, the overall credit risk of group 1 increases because the return of excess interest as principal to group 1 is delayed due to its redirection to group 2. As a result, the group 1 investor must provide a default and loss assumption for both groups 1 and 2 in order to adequately assess the overall credit exposure and expected loss of the notes backed by group 1.

Notice that the subordination is often tranched, creating AA, A, BBB, BB, B, and a non rated class, creating six distinct credit tranches. Credit tranching, as described above, is often referred to as a six-pack transaction in deference to the number of credit classes that are created.

At this point, it is important to note that both the H and Y structures may be used to securitize more than two distinct collateral groups. Each of these structures, unlike the I structure, socializes losses across a transaction.

- The H structure partially socializes losses across the collateral groups at the level of the excess interest and over collateralization, whereas the Y structure completely socializes losses.

- The Y structure, socializes losses at the level of excess interest, over collateralization, and the subordinated classes.

22.4 Shifting Interest

Private-label MBS transactions employ a shifting interest mechanism designed to increase the credit enhancement available to the senior classes. Early in the life of the transaction, typically the first 36 months, principal collections and in some cases, excess interest is paid to the senior classes only and the subordinated classes are locked out from receiving principal pay-downs.

For example, assume an I structure like that depicted in Figure 22.1. The AA, A, BBB, BB, B, and not rated classes account for at least 3.5%, 2.05%, 1.3%, 0.9%, 0.5%, and 0.3% of the capital structure, respectively, during the lockout period.

- The triple-A class is paid down faster than the credit support classes and its relative percentage interest in the underlying mortgage pool decreases.

- Concurrently, the relative percentage interest of the subordinated classes in the mortgage pools increases, affording greater loss protection to the triple-A class.

Generally, subordinated classes are locked out from receiving principal collections in the first 36 months of a transaction or until the credit enhancement level supporting the senior classes has doubled, whichever occurs later. The stepdown date is the point at which the subordinated bonds are no longer locked out and begin to receive principal collections. It refers to the reduction (stepdown) of the dollar amount of subordination as credit enhancement. With respect to the I structure under consideration, at the step down date, the mezzanine (double-A) and subordinated classes would receive their pro rata share of principal collections and begin to amortize.

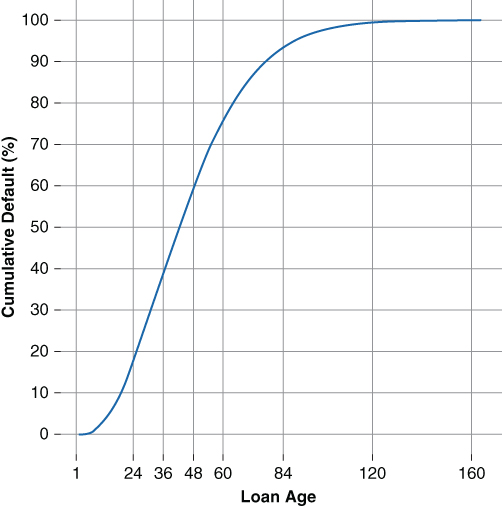

The 36-month lockout period is based on the historic mortgage default experience. Figure 22.4 illustrates a cumulative default curve based on FHLMC's loan level data. The figure shows a mortgage pool consisting of prime borrowers will experience around 40% of its total expected cumulative defaults by month 36 and by month 48 the pool will likely experience the majority (60%) of its total expected cumulative defaults, most occurring between months 24 and 36. Given the expected timing of the defaults, the early lockout of the subordinated bonds maximizes the amount of credit support available concurrent with the peak in the default timing curve. Provided the transaction passes the stepdown test at month 36 the subordinated classes will begin to receive principal collections. However, should the transaction fail its stepdown test the subordinated classes will continue to be locked out from principal collections until such time the transaction passes its stepdown test.

Figure 22.4 Agency Mortgage Default Timing Curve

22.5 Deep Mortgage Insurance MI

The issuer may purchase mortgage insurance at the time of securitization as a form of credit enhancement. Recall from Table 6.2 the presence of mortgage insurance minimizes the investor's realized loss given default. Consequently, the credit rating agencies view deep MI as a source of external credit enhancement which, in the rating agency view, reduces the amount of upfront credit support needed to achieve the desired credit ratings on those classes relative to senior/subordinated structure, which does not have issuer paid deep MI. Naturally, the investor must consider the issuers motivation—the lowest cost of funds. Thus, an issuer is willing to purchase deep MI when its cost is less than that of the capital cost of the subordinated notes—a capital structure arbitrage. In a transaction supported by deep MI the issuer pays a premium, which may come out of the cash flow of the securitization for an MI policy that covers losses on a portion of the pool. It is important to note the following with respect to deep MI as a form of credit enhancement:

- Loan level deep MI differs from a monoline wrap. A monoline wrap from a bond insurance company is an unconditional guarantee of timely payment of interest and the ultimate repayment of principal. Consequently, the investor's credit risk exposure is directly linked to the monoline insurer.

- In a deep MI transaction the loans must meet the insurer's criteria. The MI insurer specifies the characteristics of the loans such as the minimum and maximum LTV, property type, minimum and maximum borrower credit score, etc. When a covered loan defaults, the issuer must submit a claim to the insurer. The insurer may choose to cover all or a portion of the claim or may reject the claim altogether if the insurer determines that its underwriting guidelines have been violated.

From the above description, it should clear that a transaction employing deep MI is not, in the strictest sense, a self insuring structure because the overall credit enhancement levels are determined by the presence of the deep MI policy and as a result the investor bears credit risk exposure to a second party external to the transaction. A deep MI policy covers a portion of the principal balance of the loan to a pre-specified LTV ratio, typically 60% to 65%. Additionally, a deep MI policy will cover accrued interest and expenses incurred during the foreclosure and liquidation process. Conceptually, deep MI takes a second loss position behind the borrower's equity, and to the investor the liquidated loan appears to have a lower LTV ratio.

22.6 Excess Interest

Excess interest is the difference between the collateral pool's weighted average mortgage rate and the weighted average cost of the liabilities, net of fees and expenses. Generally, the underlying pool of mortgage loans (assets) is expected to generate more interest than what is paid to the classes (liabilities).

- To the extent excess interest net of fees, expenses, or derivative payments is positive, it is used to absorb losses incurred by the underlying mortgage pool.

- Once the financial obligations of the trust are met, excess interest is used to maintain overcollateralization at its target level. Factors influencing the extent to which excess interest is available to maintain overcollateralization include:

- Full or partial voluntary repayments and defaults may reduce the amount of excess spread because those borrowers with a higher mortgage rate have a greater tendency to voluntarily repay or default. In turn, the weighted average loan rate of the underlying mortgage pool declines over time, a phenomenon commonly referred to as WAC drift.

- If the realized delinquencies, defaults, and losses are greater than expected, the transaction's excess interest is reduced by the amount necessary to compensate for the cash flow shortfalls required to make a full principal distribution to the senior and mezzanine certificates in any period.

22.7 Overcollateralization

Overcollateralization is the excess of the principal balance of the pool of mortgage loans (assets) over the principal balance of the issued notes (liabilities). It is a form of internally created credit support. Excess spread, also internally created, is used to pay down and maintain the outstanding classes' principal balance below that of the pool of mortgage loans.

Overcollaterlization is either fully funded at the transaction's closing or builds over time using excess interest to pay down the principal balance of the senior liabilities until the OC reaches its targeted amount. In the case of the latter, the target OC amount is usually achieved in the early months of the transaction's life, whereas in the case of the former excess interest is used to maintain the target OCamount. Generally, the target OC amount is established as a percentage of the transaction's original principal balance and varies from one transaction to another depending on the underlying collateral composition, structure, and the rate (coupons) paid on the liabilities.

A transaction using overcollateralization as credit enhancement can sustain losses in any period equal to the amount of the currently available excess spread and overcollateralization before the subordinated classes incur a principal writedown. For example, assume an I transaction presented in Figure 22.1 and a fully funded target OC amount of 1.0%. Once the transaction's cumulative losses exceed the targeted OC amount, and if the excess spread is insufficient to cover the losses in a given period, then the lowest rated subordinated class whose principal balance is greater than zero will experience a principal writedown.

22.8 Structural Credit Protection

In addition, structural credit protection in the form of trigger events is also used. These include delinquency and overcollateralization triggers. For the most part, trigger events are based on seriously delinquent loans and cumulative losses. A seriously delinquent loan is a loan that is 60+ days past due (dpd), in foreclosure, or real estate owned (REO). These triggers are considered in effect on or after the stepdown date if either or both the delinquency and cumulative loss test(s) are not passed.

22.8.1 Delinquency Triggers

There are two types of delinquency triggers: soft trigger and hard trigger. In either case, the goal of the trigger is to manage the transaction's stepdown.

22.8.1.1 Soft Delinquency Trigger

A soft delinquency trigger dynamically links the credit enhancement to the credit performance of the underlying collateral. There are two types of soft delinquency triggers:

- A trigger based on the credit enhancement of the senior classes. This trigger specifies a target value of delinquencies as a percentage of the senior classes' credit enhancement and for the most part protects the senior class bondholders. However, because the trigger is specified as a percentage of the senior classes' credit enhancement, it becomes mechanically weaker as the senior classes pay down. In fact, under a fast prepayment scenario, the trigger may weaken tothe point that it may no longer be effective.

- A trigger based on the credit enhancement of the most senior outstanding class. A trigger of this type will not allow the stepdown if the percentage of seriously delinquent loans exceeds a target level that is tied to the credit enhancement available for the most senior outstanding class. Structurally, this trigger partially addresses the shortcomings of the delinquency trigger discussed above.

22.8.1.2 Hard Delinquency Trigger

A hard delinquency trigger is not tied to the senior classes' credit enhancement percentage. Rather, a hard delinquency trigger is stated as a fixed percentage of the mortgage pool's current collateral balance. A hard delinquency offers the following advantages over a soft delinquency trigger.

- A hard delinquency trigger mitigates adverse selection risk due to faster than expected prepayments.

- A hard delinquency trigger's ability to prevent stepdown does not weaken with an increase in subordination to the senior classes.

22.8.2 Overcollaterlization Step-up Trigger

The overcollateralization step-up trigger increases a transaction's target OC amount, rather than stopping the release of OC to a higher level if the mortgage pool's cumulative losses exceed a specified amount. The OC step-up trigger provides the advantage of causing the OC target to increase during the later stages of the transaction's life. However, due to the phenomenon of WAC drift, it is possible that when cumulative losses cross the specified level excess spread may be insufficient to build the additional overcollateralization called for by the trigger event.

22.8.3 Available Funds Cap

The term available funds cap (AFC) refers to the singular truism of MBS investing: a bondholder may only be paid interest up to the amount of the net interest that is generated by the underlying pool of mortgage loans. The AFC arises when a transaction's liabilities are floating and it is collateralized by hybrid adjustable-rate loans. Most hybrid adjustable-rate loans have a fixed-rate period, commonly from one to five years, which limits the interest available to the trust. All adjustable rate loans have both a periodic and a life cap. Both of these limit the interest available to the trust needed to meet class interest payments after trust fees and transaction expenses. Together, they give rise to the available funds cap.

Most floating rate MBS classes are indexed to one-month LIBOR and reset monthly. The note rate on adjustable- and hybrid adjustable-rate loans in MBS transactions often reference several interest rate indexes like six-month LIBOR or the one year Constant Maturity Treasury (CMT) and their note rates do not reset monthly. This difference creates both an index and rate reset timing mismatch. The differing indexes used to set the interest rate on the pool of mortgage loans (assets) versus the one-month LIBOR index used to determine the classes' (liabilities') interest rate creates additional risk, which is commonly referred to as basis risk.

The calculation of the initial available funds cap is relatively straight forward. First, subtract expenses (servicing fees, trustee fees, IO strip, and net swap payments) from the original weighted average coupon on the underlying pool of mortgage loans. Once the cost of the liabilities have been accounted for, the available excess spread can be calculated as outlined in Table 22.1. Consider the following:

- A transaction collateralized by a mortgage pool of 7/1 hybrid ARM loans with a current rate of 3.125% and a life cap of 8.125%

- Current one-month LIBOR of 0.25%

- No swap hedge used in the transaction

Table 22.1 Available Funds Cap Calculation

| Initial AFC(%) | Life AFC(%) | ||

| Wtd. Avg. Gross WAC | 3.125 | Weighted Avg. Life Cap | 8.125 |

| Less Servicing Fee | 0.25 | Less Servicing Fee | 0.25 |

| Less Trustee Fee | 0.05 | Less Trustee Fee | 0.05 |

| Less IO strip (if any) | 0.00 | Less IO strip (if any) | 0.00 |

| Less Deep MI | 0.25 | Less Deep MI | 0.25 |

| Less Net Swap Pmts. (bps) | 0.00 | Less Net Swap Pmts. (bps) | 0.00 |

| Net Initial AFC | 2.575 | Net Life AFC | 7.575 |

| Weighted Avg. Bond Spread | 0.10 | Weighted Avg.Bond Spread | 0.10 |

| Current 1-Mo. LIBOR | 0.25 | ||

| Weighted Avg. Bond Coupon | 0.35 | ||

| Initial Excess Spread | 2.25 |

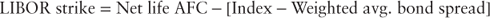

The initial available funds cap is 2.575%, the initial excess spread is 2.25%, and the net life cap is 7.575%. The LIBOR strike, first introduced in Section 18.4, can also be calculated from Table 22.1 as follows:

22.9 Hedging Asset/Liability Mismatches

Hedging the basis risk in a PLMS transaction can be done using either interest rate caps, interest rate swaps, or a combination of both. Asset/liability hedges are required in a transaction for the following reasons:

- The available funds cap refers to the fact that the coupon on a floating rate bond (liability) is limited to the weighted average note rate on the underlying loans (assets), less the expenses of the trust. The trust's expenses may include any or all of the following: trustee fees, surety fees, bond surety fees, IO strip, and mortgage insurance fees. Furthermore, the timing mismatch between adjustments to the liability rate (generally monthly) and the asset rate (generally semi-annual or annual) may create a temporary interest shortfall due to the presence of periodic caps that may limit the weighted average loan rate on the mortgage pool relative to the weighted average rate of the classes.

- A mortgage securitization may include hybrid ARM loans with fixed-rate periods ranging from 2 to 10 years, as well as term fixed-rate loans. In turn, the nature of the underlying collateral may create an asset/liability mismatch of floating-rate classes (liabilities) and fixed-rate assets (the mortgage pool). Consequently, the mismatch must be hedged to preserve the excess spread in a rising interest rate environment.

22.9.1 Hedging with Interest Rate Caps

Hedging with an interest rate cap (Figure 22.5) requires the issuer to purchase a cap in order to hedge the asset/liability mismatch thus incurring an upfront cost. The cap contract is not an asset of either the lower or upper tier REMICs. Rather, cap payments are made to a distribution account after fees. The hedge is straightforward:At the closing of the transaction, the trust enters into a cap contract with a cap provider. The cap contract states the LIBOR strike and the notional balance on which the contract is based. In addition, the cap contract may specify a maximum LIBOR rate beyond which the cap will not pay—a cap corridor.

Figure 22.5 Hedging with an Interest Rate Cap

Generally, the cap contract is struck to cover the hybrid ARM fixed-rate period. For example, a transaction collateralized by 7/1 hybrid ARM loans may enter into a cap contract covering the first 84 distribution dates of the transaction. Under the agreement, the cap counterparty agrees to pay the trust the excess of the LIBOR strike up to a maximum value based on an actual/360 basis. The cap payment, if made by the cap counterparty, is deposited to the Net WAC carryover account and made available to pay the interest to each class.

22.9.2 Hedging with Interest Rate Swaps

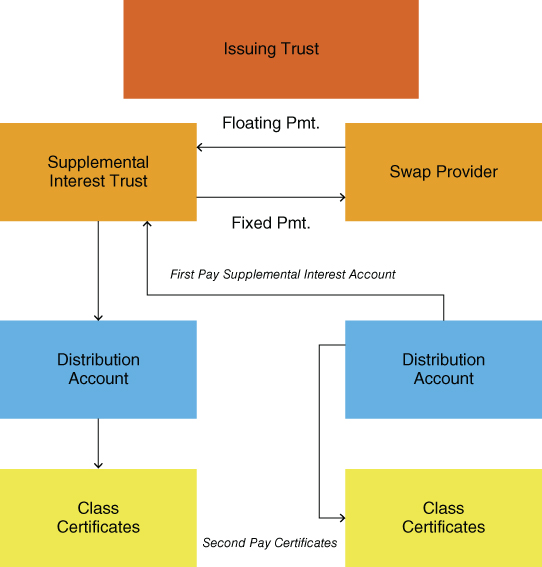

If the transaction is hedged with an interest rate swap (Figure 22.6), it is held in a supplemental interest trust which is not considered an asset of either the lower-or upper-tier REMICs. The swap payments become fees and expenses of the trust and net swap payments by the trust are withdrawn from amounts on deposit in the distribution account.

Figure 22.6 Hedging with an Interest Rate Cap

On the distribution date, the supplemental interest trust pays the swap provider a fixed rate and the swap provider pays the supplemental interest account a floating payment equal to one-month LIBOR. The swap payments are based on the amount of the outstanding balance of the senior and mezzanine classes. A net swap payment is made on the distribution date as follows:

- If the fixed payment is greater than the floating payment, the supplemental interest trust pays the swap provider.

- If the fixed payment is less than the floating payment the swap provider pays the supplemental interest trust.

If the supplemental interest trust is required to make a payment to the swap provider because the fixed payment is greater than the floating payment, the trust is required to make a payment from the distribution account to the supplemental interest account. In this case, the payment to the supplemental interest account is made before interest distribution to the class certificates.

From the discussion above, it should be apparent that a PLMBS transaction which relies on either a cap agreement or an interest rate swap to hedge basis risk is not, in the strictest sense, a self-insuring structure. Indeed, the timely payment of interest to the class certificate holders is dependent on the performance of the cap or swap counterparty. Thus, by extension the trust is exposed to the creditworthiness of the cap or interest rate swap provider—a third party to the transaction.