Twelve-wired Birds of Paradise (details). Joseph Wolf. Hand-coloured lithograph from D. G. Elliot’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae (1873).

Twelve-wired Birds of Paradise (details). Joseph Wolf. Hand-coloured lithograph from D. G. Elliot’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae (1873).

Two adult male Twelve-wired Birds of Paradise. William Hart and John Gould. Hand-coloured lithograph from Gould’s Birds of New Guinea (1875–88).

The Twelve-wired Bird of Paradise

Genus Seleucidis

The second distinct kind of bird of paradise to arrive in Europe, of which we have any record, is a very odd one, the Twelve-wired. Indeed, it is so odd that many might be surprised to know that it even belongs to the bird of paradise family at all. But to hunters collecting plumes in the forest of New Guinea, plumes are plumes. And plumes it has.

They sprout from the male’s flanks and are the same golden colour as the hunters’ usual quarry, the Greater and Lesser species. And they are unquestionably plumes, for the barbs on either side of each quill do not zip together like flight feathers and are nothing more than gauzy filaments. But they are not erectile and each bunch contains six that are twice the length of the rest. In their lower sections, which are buried within the rest of the plumes, these strange feathers are white and fringed on either side with very short barbs. But where they extend beyond the main bunch they are no more than thin naked quills which are a shiny jet black. These are the wires that give the species its name.

Doubtless the golden plumes were enough to attract hunters in New Guinea and persuade oriental traders to accept the skins, perhaps at a lower price, as second-best birds of paradise. At any rate, at the end of the sixteenth century, one example found its way across Asia and Europe and into that cabinet of curiosities assembled by the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II (1552–1612) and kept at his castle in Prague.

Around the year 1600, he commissioned artists to produce a series of paintings of animals and birds living in his menagerie, and also of interesting specimens from his curiosity collection. Acting on the royal instruction, Dutch artist Joris Hoefnagel (1542–1601), or perhaps his son Jacob (1575–c.1630), painted a picture of the Twelve-wired.

The specimen must have arrived in Europe only recently, for the artist shows the colour of its flank plumes as bright yellow and – as we now know – they always fade to white after a few years. Indeed, they do so even in live captive specimens if they are not given pandanus nuts in their food. The emperor’s specimen, nonetheless, was clearly badly mangled. Its neck seems to have lost some of its feathers, for it is very scrawny, and instead of twelve wires, the bird has only ten, five on each side. That at least is understandable, for the wires, the quills, can become very brittle with age. Its other disfigurements, however, may have been inflicted by the native hunters who collected the specimen in New Guinea and treated it in the same way as other more famous species, the Greater and the Lesser, cutting off its wings and feet in order to emphasise the splendour of its similarly coloured golden flank plumes, and removing the skull to make preservation of the skin and feathers easier. Certainly there are no signs of either wings or feet in the painting, and the bird’s body and tail appear to be little more than a black tube with a clump of golden plumes flaring on either side like the engines of a jet aircraft.

It is easy to sympathise with the predicament Hoefnagel faced when he came to paint his picture. After all, he was confronted with a dried relic bearing only a passing resemblance to the creature in life, and he had, of course, never had the opportunity of seeing a living individual. Furthermore, birds of paradise – with their often peculiar arrangement of plumes, fans and wires – hardly conform to the morphological patterns shown in more familiar birds.

Perhaps because the illustrations Rudolf commissioned remained the private property of the Habsburgs, the painting was long overlooked by naturalists, and the Twelve-wired remained largely unknown in Europe. Even the great Carl Linnaeus failed to give it a scientific name in the 1758 edition of his Systema Naturae.

A Twelve-wired Bird with a Scarlet Ibis below. Joris or Jacob Hoefnagel, c.1600. Gouache on parchment, 36 cm × 27 cm (14 in × 11 in). National Library of Austria, Vienna.

Twelve-wired Bird of Paradise, painted soon after François Daudin scientifically described the species, and showing the faded plumes on which he based his description. Jean-Gabriel Prêtre, c.1810. Watercolour on paper, 52 cm × 38 cm (21 in × 15 in). Private collection.

It wasn’t until the year 1800, some two hundred years after Hoefnagel painted it, that the Twelve-wired was named scientifically and registered as an accredited member of the Bird of Paradise family. Then a French naturalist, François Daudin (1774–1804), a man who took up zoology despite the fact that his legs had been paralysed by a childhood disease, published a description of it. He recognised that although it was indeed a bird of paradise it was sufficiently different from any other species to be given a genus of its own. Searching, perhaps, for a name that might reflect its paradisal connections, he called it Seleucidis, a word used by the Greeks in classical times for migrant birds that appeared from nowhere – perhaps even paradise – and ate the locusts that threatened their crops. This might be considered to be a little over-imaginative, but the specific name he chose – melanoleuca – was even less suitable, for that word means ‘black and white’. Clearly the particular specimen that he examined was an ancient one, the plumes of which had already faded.

In the years that followed, European artists who had the job of imagining how the bird appeared in the exotic forests on the other side of the world, made a somewhat better job of it than Hoefnagel. But they were all baffled by the twelve naked quills, the wires.

Just a year after Daudin had described the species, François Levaillant began to publish the first systematic catalogue of the bird of paradise family. It took him five years to complete, and the book’s success rests largely on the illustrations engraved after watercolours produced by the incomparable Jacques Barraband (1767–1809), an artist who was second to none in capturing the exquisitely coloured plumage of tropical birds, whether they were parrots, toucans, cotingas or birds of paradise. Barraband’s remarkably detailed pictures cannot be doubted in terms of the accuracy of these details. There is little question that he was using stuffed birds as models, and in some senses his paintings can be regarded as belonging to the genre of still life. They are crystal-clear depictions of the objects that lay before him, and because most of his watercolours were preserved for almost two centuries in albums well away from the fading caused by exposure to light, they remain in pristine condition.

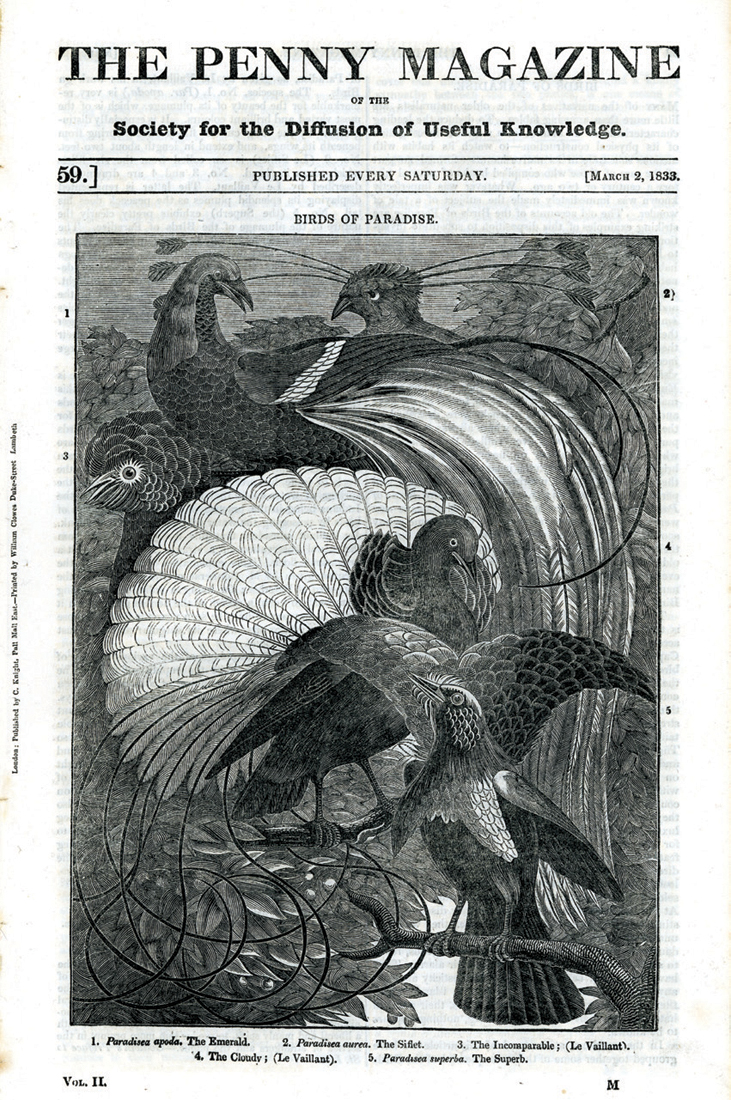

Barraband called the Twelve-wired Le Nebuleux, a word that can mean either ‘obscure’ or ‘hazy’. Perhaps he had the second meaning in mind because he shows the displaying male bird with his flank plumes in a great cloud above his back, with the wires projecting below symmetrically arranged like the extravagant curlicues and flourishes drawn by a practised calligrapher.

But there is a problem. Barraband produced two pictures and they show birds in different attitudes, but with exactly the same plumage features. But do they indeed show the Twelve-wired species? In fact, only ten wires are depicted in each image. This is easily explainable. It might well be that, like Hoefnagel’s specimen, a couple of them had broken off.

More seriously, however, the bird’s under-parts, which in life are white, are shown as black, the wings brown instead of black, and the beak entirely straight and thin, rather than showing the strong downward curve that is typical of the species. As the rest of his work shows, Barraband was meticulously accurate and it seems unlikely that he would have deliberately misrepresented the specimen from which he was working.

Was it perhaps incomplete and he had to imagine what the hinder part of its belly and the beak were like? Or maybe the specimen was in fact a hybrid, with a parent from a black-bellied species such as a Riflebird, hybridisation being not uncommon among members of the family. His two pictures, at any rate, remain somewhat problematic, even apart from the elegant posture of the bird’s decorations.

The cover of The Penny Magazine for 2 March 1833, one of many illustrations that leaned heavily on the work of Jacques Barraband.

Two enigmatic images of birds that resemble Twelve-wired Birds of Paradise. Jacques Barraband, c.1800. Watercolour on paper, 52 cm × 38 cm (21 in × 15 in). Private collection.

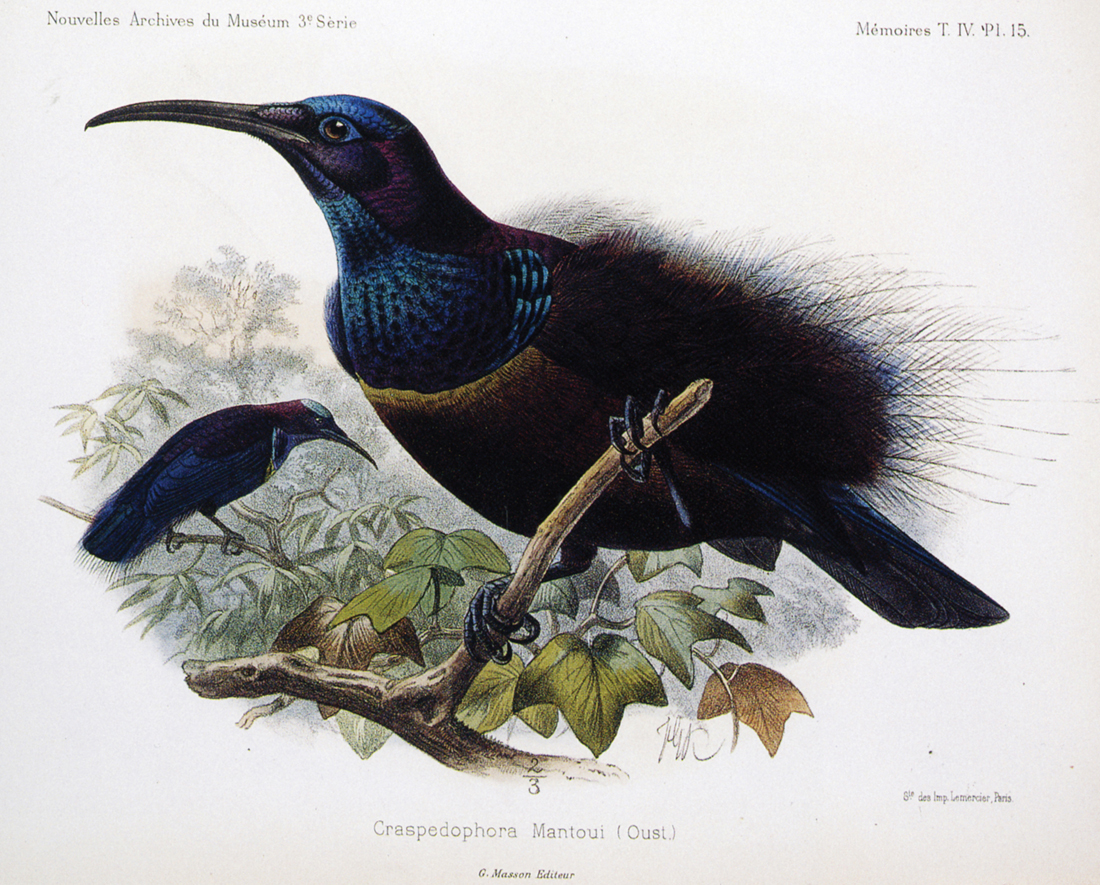

Mantou’s Bird of Paradise, a hybrid between the Twelve-wired and the Magnificent Riflebird. J. G. Keulemans. Hand-coloured lithograph from Nouvelle Archives du Museum, Paris (1892).

To add even more mystery, an actual hybrid between the Riflebird and the Twelve-wired (and defined as such by plumage similarities) was recorded almost a century later, but it looks nothing like the bird painted by Barraband. A beautiful lithograph by the celebrated ornithological illustrator J. G. Keulemans (1842–1912) shows it has no close connection.

Whatever the truth about Barraband’s two enigmatic paintings, his influence – through his engravings rather than the original watercolours – persisted during the first few decades of the nineteenth century, and his work was regularly plagiarised in books, popular magazines and journals.

A picture dating from around the same time as Barraband’s, illustrates a specimen in perhaps a more literal way. It may have been made by Sarah Stone (1760–1844), an artist who made a speciality of drawing museum specimens, or by the influential English ornithological writer John Latham. It shows the wires as much more untidy and straggling.

Male Twelve-wired Bird of Paradise. Artist unknown, but probably Sarah Stone, c.1800. Watercolour on paper, 25 cm × 30 cm (14 in × 12 in). Private collection.

Twelve-wired Bird of Paradise. Friedrich Specht. Steel engraving from Richard Lydekker’s The Royal Natural History (1894–96).

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, William Hart, working for John Gould, interpreted the wires in a different way. Maybe he thought that their bent crooked shapes were caused by the way the specimen had been packed. At any rate, he shows them six a side, straightened out and neatly folded over the male’s back. Joseph Wolf, in Elliot’s great folio catalogue of the family, shows them sprouting rather jauntily on either side of the male’s body.

Adult male and female Twelve-wired Birds of Paradise. Joseph Wolf and Joseph Smit. Hand-coloured lithograph from D. G. Elliot’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae (1873).

In reality, the wires are not arranged in any of these ways. Friedrich Specht, illustrating Richard Lydekker’s The Royal Natural History, which was published in 1894, portrayed them more accurately than any of his predecessors. They radiate around the male’s tail like unevenly separated spokes of a wheel. But what purpose can they serve? Female birds of paradise are celebrated for their preference for extravagant visual displays by their partners. It is that predilection that has led to the development of fantastic plumes in the males. But how could the female Twelve-Wired regard this jumble of naked quills as spectacular? It must have some other attraction. But what?

Several artists had certainly tried to depict male and female birds together, but none had attempted visually to explain just what the plumes and wires meant, nor how they were used. Then, in the early 1950s, an American artist named Walter Weber (1906–79) produced a revolutionary series of bird of paradise paintings for National Geographic magazine. He was the first to show the Twelve-wired male with breast fan erected, but he assumed that the males display in groups, as the Greater bird does. The truth, however, is very different.

The Twelve-wired’s favourite habitat is the fringe of pandanus swamps around New Guinea’s coasts and rivers. Like nearly all species in the family, the males are promiscuous. Each has his favourite display perch, usually an extremely conspicuous one such as a snag, a bare dead tree trunk standing in a swamp. He flies to it every morning at dawn and then, standing on its summit and slowly turning, he begins to call with a single extremely loud throaty note. If a female is attracted by it, she will land beneath him on the snag. The male, much excited by her arrival, erects his breast fan, and lifts and expands his yellow flank plumes, exposing his naked thighs which are a brilliant pink.

Once this moment has passed, the two begin to dance, sparring with their beaks as they circle the trunk, the male above, the female beneath. Slowly the duo moves downwards. Eventually she decides to retreat no further and takes off, flies upwards and lands on the tip of the snag. The male chases up the trunk towards her, and when the two are once again within pecking distance, they repeat their sparring duet.

The Display of the Twelve-wired Bird of Paradise. Walter Weber, c.1950. Oils on board.

They may do this several times until, suddenly, the male swivels round so that he faces upwards and the female is faced with his tail. Then with slow languorous movements, he backs down towards her and brushes her face with his twelve naked wires.

The female Twelve-wired Bird of Paradise has taken a different fancy from her cousins. Her climactic thrill in courtship is not visual. It is tactile.