The Ruling Passion – sometimes called The Ornithologist (detail). John Everett Millais, 1885. Oils on canvas. Kelvin Grove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow.

The Ruling Passion – sometimes called The Ornithologist (detail). John Everett Millais, 1885. Oils on canvas. Kelvin Grove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow.

Genus Cicinnurus

The Emperor Rudolf’s cabinet of curiosities in Prague was a rich one. Alongside the Greater Bird of Paradise, the Lesser, and the Twelve-wired lay another bird skin. The scholars who catalogued the collection also called it a bird of paradise, but it was very different from the others. They were all crow-sized; this one was scarcely bigger than a thrush. They had gauzy flank plumes; it had none. But its plumage was, nonetheless, sensationally beautiful. Above, it was a regal scarlet; below, a silky white with a narrow iridescent green band across its breast. The feathers on its head were so short and soft they looked like velvet. Those on the back glistened like spun glass. Most remarkable of all, it had two long wire-like quills sprouting from its tail. These, however, were not entirely naked like those of the Greater Bird or the Lesser, but barbed at the tip and curled into a tight, button-like spiral of a metallic green that matched the colour of the breast band. It was these spirals that eventually led to the bird being given its scientific name of Cicinnurus, a word derived from Greek, meaning a ringlet or a curl of hair.

Judging from early descriptions, this specimen, like many other imported examples, lacked legs. That, no doubt, was why it was called a bird of paradise. Bestowing that name was not a declaration of family relationship, for the idea that groups of similar animals might be biologically related was not one that anyone held in the seventeenth century. Then, each species was believed to have been individually created by God. So the name ‘bird of paradise’ meant no more than that the birds came from that part of the world, wherever it might be.

King Bird of Paradise and Greater Bird of Paradise, painted from specimens in the collection of the Emperor Rudolf II. Joris or Jacob Hoefnagel, c.1600. Gouache on parchment, 25 cm × 36 cm (10 in × 14 in). National Library of Austria, Vienna.

At the beginning of the seventeenth century, the myth of leglessness took a knock. The Emperor Rudolf II had a Frenchman serving as a naturalist in his court in Prague. His name was Charles Lecluse (1526–1609), though, as was the custom for scholars at the time, he used a Latinised version of his name, Carolus Clusius, in his publications. He knew of paradise bird skins in the emperor’s collection and had believed the stories about their celestial origins. But in 1593, he was appointed professor in the newly founded University of Leiden near the northern coast of Holland. There he was one step closer to the source of the paradise bird skins, for they were now being brought back in some numbers on board Dutch merchantmen returning from the East Indies with cargoes of spices. The sailors told him that these skins came from a land east of the Spice Islands that they called Tanna-Besar. The words in Malay mean ‘Big Land’. This may have referred to the Aru Islands on which the plume trade was focused and which was and is the home of several bird of paradise species. Or, more likely, it referred to New Guinea, the immense island northeast of Aru where the birds existed in even greater variety. And some of these skins that Professor Clusius saw were entire – complete with wings and legs.

So in his book, in which he discusses the natural history of birds, he firmly dismissed the legend that the birds floated in paradise. Nonetheless he repeated other stories about the King Bird. A single one, he said, regularly accompanied flocks of the plumed birds, flying high above them. If a hunter managed to shoot one down with his bow and arrow, then the whole of the flock would ‘fall together with him and yield themselves to be taken as refusing to live after they had lost their king.’

He first saw a specimen of the King in Amsterdam in 1603. It belonged to a merchant ‘who was wont to buy up such exotic things among the mariners returning home that he might make a great profit from selling them again to others.’ Clusius did not buy it, but the following year he saw another one and this he managed to borrow for long enough to have its picture drawn for inclusion in his book. Although nearly all of the other illustrations had already been engraved and were ready for printing, he managed to add this image, since ‘no man hitherto (as far as I know) hath set forth the like.’ And there the King makes his first public appearance, lying on his back with his extraordinary button-tipped wires dangling – but still legless.

Although Clusius, like his predecessors, grouped the species of paradise birds together because he believed they came from the same place, we now know that birds of paradise are in fact closely related biologically and descended from a common ancestor. The dramatic differences between the males are only skin-deep. The unornamented females, though differing in size, are remarkably similar, just as you might expect from closely related species. They have brown upper-sides and pale lower ones which in many species, including the Twelve-wired and the King, are barred with black.

The displays of the male King Bird remained unknown until well into the twentieth century. His performances not only show off his physical beauty but his skill as a dancer. Each male performs entirely by himself on a specially chosen and regularly used branch. He starts by cupping his wings and fluffing out his scarlet upper breast shield. Then he erects a pair of brown fans which are fringed with the same iridescent green as the breast band. As he becomes more excited, he starts to thrash his wires with their green terminal buttons from side to side. Suddenly he swings over and continues his wire-thrashing while hanging upside down. This continues for a few seconds. Then, closing his wings and glancing from side to side as if he were checking that there is someone around who will approve of his final trick, he swings vigorously from side to side like a pendulum. If there has indeed been a female watching this complex performance and she still remains nearby, he will fly off to her and the pair will copulate.

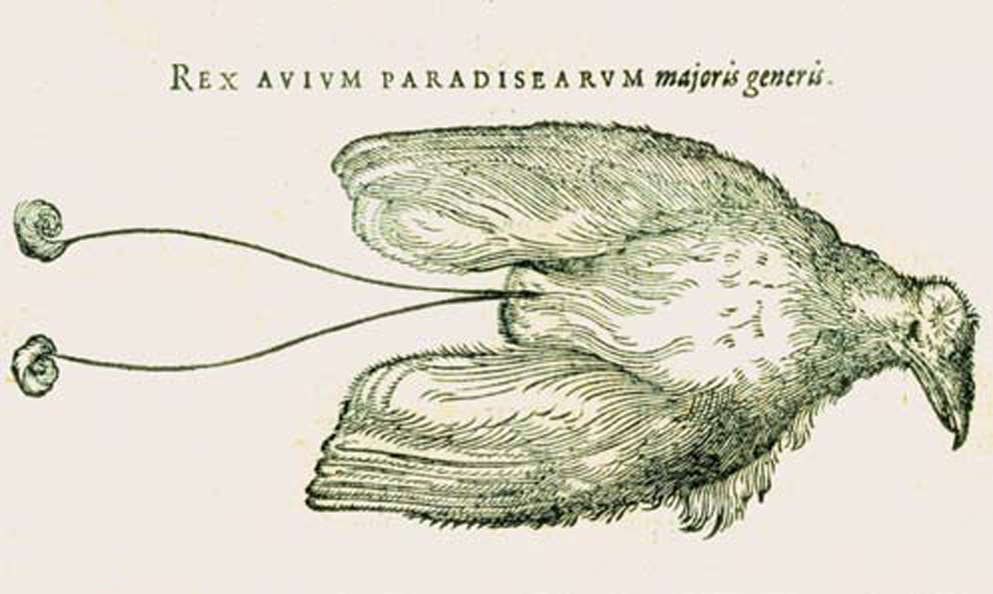

The crudely drawn illustration that Carolus Clusius included in his book Exoticorum Libri Decem (1605).

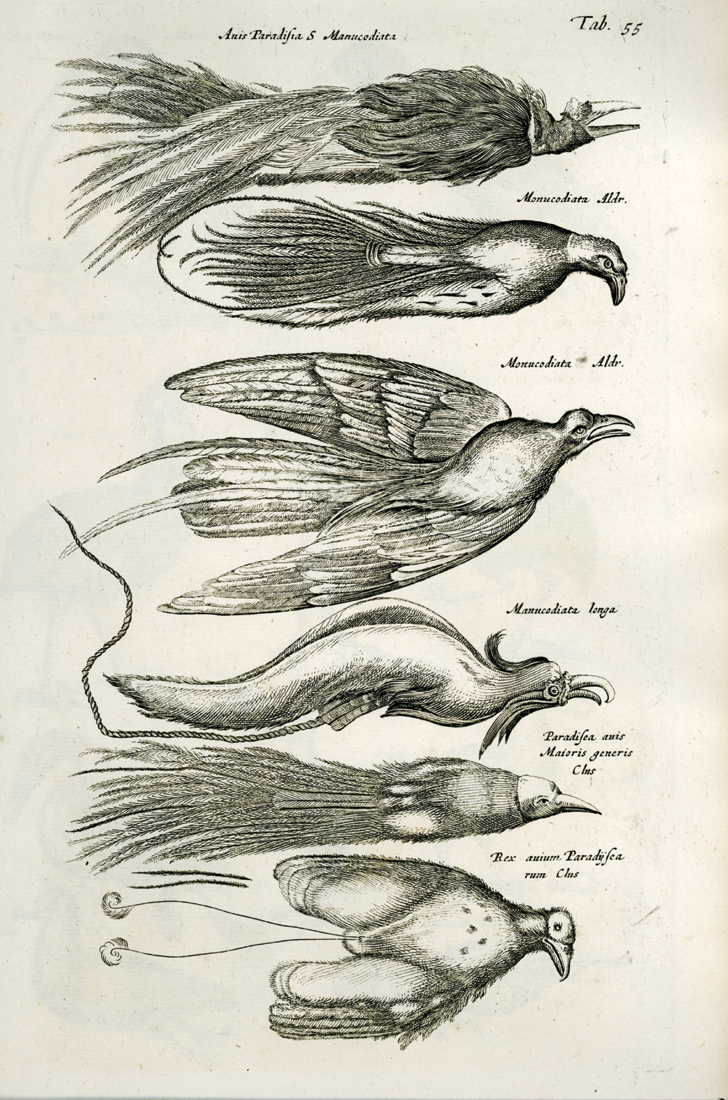

Birds of Paradise, an engraving by M. Merian. This picture was included in an early edition of J. Jonston’s Historia Naturalis de Avibus (1657). The illustration of the King Bird is clearly based on Clusius’s picture, just as three of the plumed birds are copied from Aldrovandus.

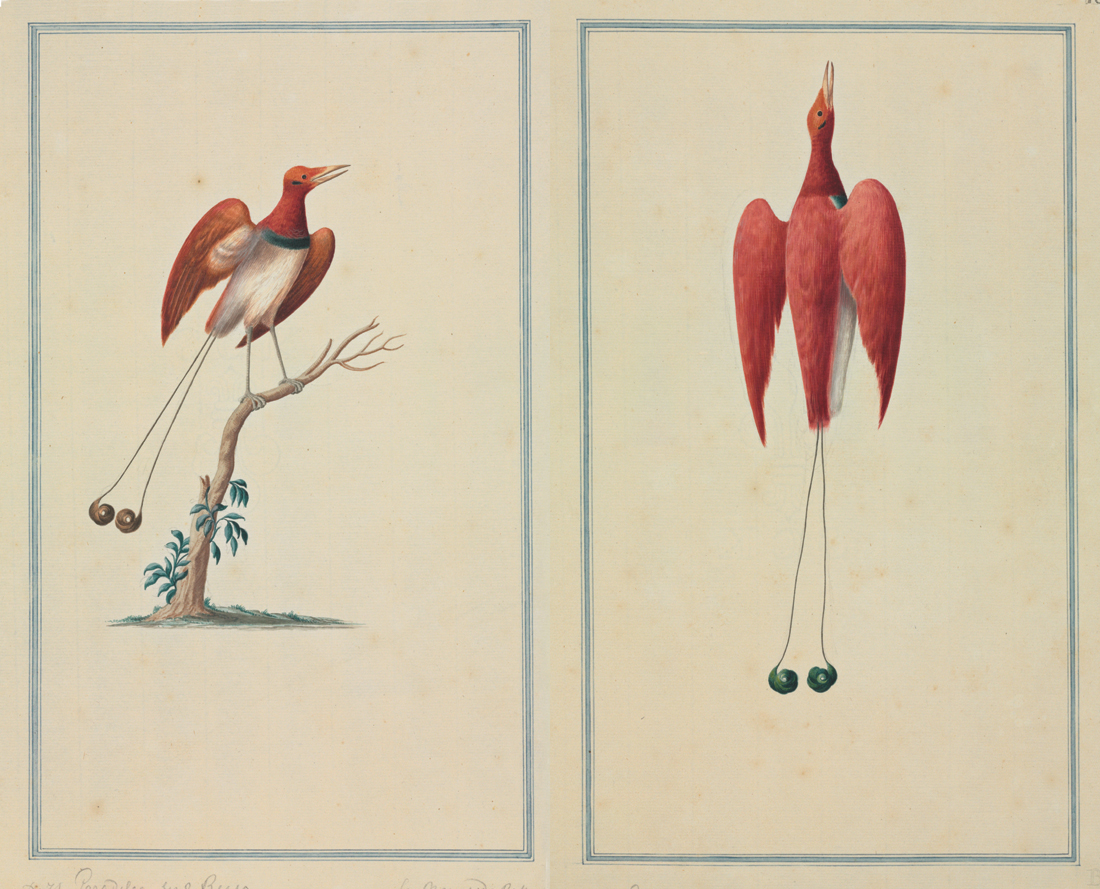

Two early images of male King Birds painted in Java, one showing the dried bird skin with feathers attached, the other showing how the artist thought the bird might have looked in life. Pieter Cornelius de Bevere, c.1750. Watercolour on paper, each 50 cm × 35 cm (20 in × 14 in). The Natural History Museum, London.

Often, of course, she departs before he gets that chance, but either way he will, with seemingly unquenchable enthusiasm, repeat the whole performance for the benefit of the next female that comes by.

It is not surprising that the Greater Bird, the Lesser, the Twelve-wired and the King were the first of the family to reach Europe, for all are to be found in the coastal regions of New Guinea. No European boats had yet ventured to sail up any of New Guinea’s huge rivers where the tribal people were notoriously aggressive and dangerous. So specimens of birds from any distance inland were hard to come by. Nonetheless, some did reach European hands.

In 1771, the French Superintendent of Mauritius, the island in the Indian Ocean then known as Île de France, determined to break the Dutch near-monopoly of the spices by introducing nutmeg plants to his island. So he despatched a number of ships to the Spice Islands to try to collect some. On board one of them went his nephew, Pierre Sonnerat (1748–1814). At the island of Salawati, lying just off the western tip of New Guinea, he met with the same experience as Magellan’s men 250 years earlier. The local Rajah presented him with bird of paradise skins.

On his return to France Sonnerat published an account of his travels which he boldly entitled Voyage à la Nouvelle-Guinée (1776), in spite of the fact that he had never set foot on the mainland. Nonetheless, he brought back with him a large collection of bird skins. Doubtless, the Rajah and his men were no more fussy about the actual truth of the skins’ origins than Magellan’s informants had been. If the attribution of a romantic and far distant source improved the price then so much the better. Some skins, for which Sonnerat surely gave a very high price indeed, must have seemed truly extraordinary, for instead of wings they had flippers. They were penguins. These, he assured his readers, came from Papua, as New Guinea was then known. One, judging from the white patch on the back of its head, was a Gentoo, a species that occurs all round the then undiscovered and uninhabited continent of Antarctica and sometimes wanders as far north as New Zealand and Tasmania. That particular skin has now gained immortality. The rules of scientific nomenclature decree that the first name used for a properly described species must have priority over any later one. So the Gentoo penguin, on the basis of the bogus provenance of this one skin, is now known to zoology as Pygoscelis papua.

Male King Bird of Paradise. Jacques Barraband, c.1800. Watercolour on paper, 52 cm × 38 cm (21 in × 15 in). Private collection.

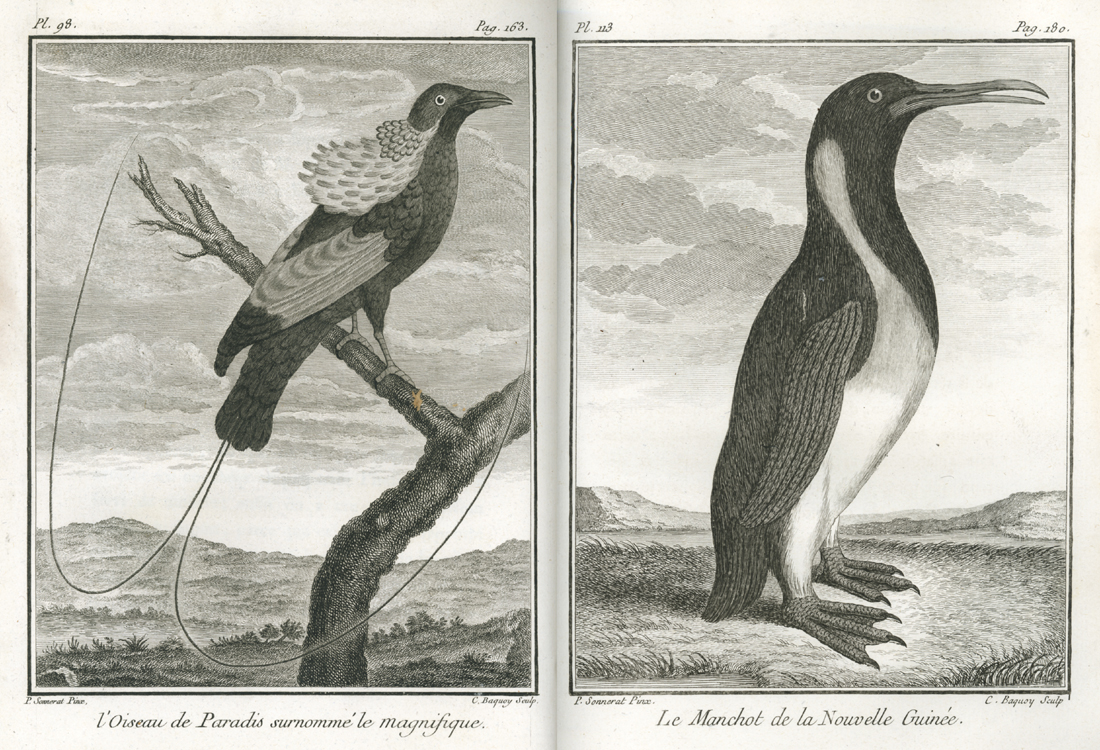

Sonnerat also described six species of birds of paradise. As well as a reasonably accurate King Bird, he illustrates another, of approximately similar size, which lives further in to the interior of New Guinea. He calls it ‘L’oiseau de Paradis surnomme le magnifique’ and accordingly it became known both in English and in French as the Magnificent Bird of Paradise.

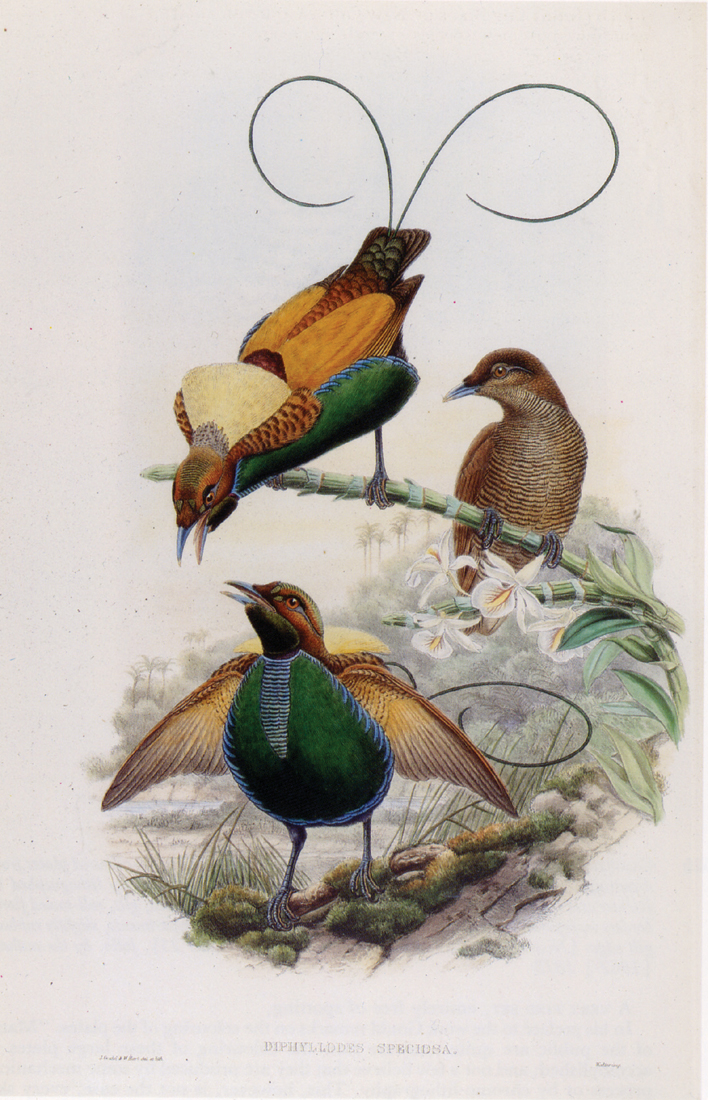

At first sight the male seems very different indeed from the King Bird. His chest is emerald green, his back orange and behind his head he has a sulphur-yellow cape. It is true that, like the King, he has two naked quills projecting from his tail, but these lack the King’s green terminal buttons and each curls outwards to form a nearly complete circle. In fact males of the species seem so different from anything else that ornithologists invented a new generic name for it – Diphyllodes, a Greek word meaning ‘double leaf’ and presumably referring to the shape outlined by these quills.

The female Magnificent, however, wears a version of the standard female costume and is almost identical to the female King, except for a pale blue stripe behind the eye which the female King lacks. So the latest classification of the family now recognises the affinity between the two species and calls the Magnificent, scientifically, not Diphyllodes but Cicinnurus magnificus.

There are now not just two but three species recognised in the genus Cicinnurus, but although the closeness of relationship between these has only recently been fully appreciated, two feature together in a fascinating painting by one of the nineteenth century’s greatest artists.

Sir John Everett Millais (1829–96) began his artistic career as a rebellious Pre-Raphaelite, but ended it as a pillar of the artistic establishment, with a knighthood and the presidency of the Royal Academy of Arts. Somewhere in between these extremes he visited John Gould at his house in London.

Gould was on his deathbed but was so enthused by the visit of the great painter that he couldn’t resist showing off some of his most fantastic bird specimens. Perhaps it even gave him the opportunity to look at them himself for the last time. Calling for his daughters (apparently, no-one else was allowed to touch his specimens), he asked them to take some of the most precious birds from their cabinets and bring them to his bedside. Among these treasures were, of course, birds of paradise.

Two illustrations from Pierre Sonnerat’s Voyage á la Nouvelle-Guinée (1776).

Male Magnificent Bird of Paradise.

The Gentoo Penguin that Sonnerat erroneously believed came from New Guinea.

Two male Magnificent Birds of Paradise with a female. William Hart and John Gould. Hand-coloured lithograph from Gould’s Birds of New Guinea (1875–88).

So taken was Millais by the scene that after he had left he decided to re-create it. By the time he did so, Gould was dead, so the great painter posed some of his own family members as models for his picture, and scattered across it various bird specimens (a Quetzal, for instance, is shown in the hands of the girl sitting at the left of the painting). Whether or not Gould had actually shown him a Cicinnurus species is not known, but there in the painting one lies on the covers of the bed (with just the curls of its tail showing), while the old gentleman playing the part of Gould holds up a stuffed King for close perusal.

In the painting, the careful rendering of the preserved birds may look beautiful, but it can hardly convey the sensational appearance of the living creatures. The male Magnificent’s display succeeds in showing off each one of the exquisite features of his unique costume. He displays, not high in trees but close to the ground, and selects a site in which there are a number of young saplings. He snips off any lower leaves that might prevent a clear view and spends many hours every day cleaning the ground beneath, removing every twig and dead leaf, until he has created a patch of bare earth several metres across. This is his court, the stage on which he will perform.

He usually dances there soon after dawn. First he pulses his green breast shield. If a female appears, he may inflate it so much that it becomes heart-shaped and extends up around his neck on either side of his head. If she stays, his excitement mounts and he erects his yellow cape to form a circular fan behind his head. He cocks up his two circular wires so that they stand at right angles to his body. And if he becomes particularly passionate, he opens his beak to expose the lining of his mouth which is a bright enamelled green.

There is some variation in the shape and colour of these adornments between individuals, perhaps giving scope for a female to choose the particular male that delights her the most. Richard Bowdler Sharpe decided that these differences were sufficiently marked for him to define three different species. So he allocated a plate to each of them in his Monograph of the Paradiseidae, the last of the great bird books of the nineteenth century. Each is shown in a different posture. But not one of them gives any idea of the way in which the Magnificent male bird actually shows off his costume to his female. Today taxonomists have decided that there is only one species, Cicinnurus magnificus.

The Ruling Passion (sometimes called The Ornithologist). John Everett Millais, 1885. Oils on canvas, 160 cm × 215 cm (63 in × 85 in). Kelvin Grove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow.

Three images that Richard Bowdler Sharpe used to justify his belief that the Magnificent Bird could be split into three distinct species. Today, these distinctions are regarded as invalid and only one species (Cicinnurus magnificus) is recognised.

(Top left) Watercolour by William Hart, c.1890. 59 cm × 30 cm (24 in × 12 in). This is the original painting on which one of the plates in Richard Bowdler Sharpe’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae (1891–98) is based. Sharpe called this form Diphyllodes hunsteini. Private collection.

(Centre right) The hand-coloured lithograph by William Hart from R. Bowdler Sharpe’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae that was produced from the facing watercolour. Hart himself copied his design on to a lithographic stone with a wax pencil and then the colours were added by hand by specialists using Hart’s original watercolour (which is now perhaps slightly faded) as a guide.

(Top corner) Hand-coloured lithograph by William Hart from R. Bowdler Sharpe’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae. Sharpe called this form Diphyllodes chrysoptera.

(Bottom corner) Hand-coloured lithograph by William Hart from R. Bowdler Sharpe’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae. Sharpe called this form Diphyllodes seleucides.

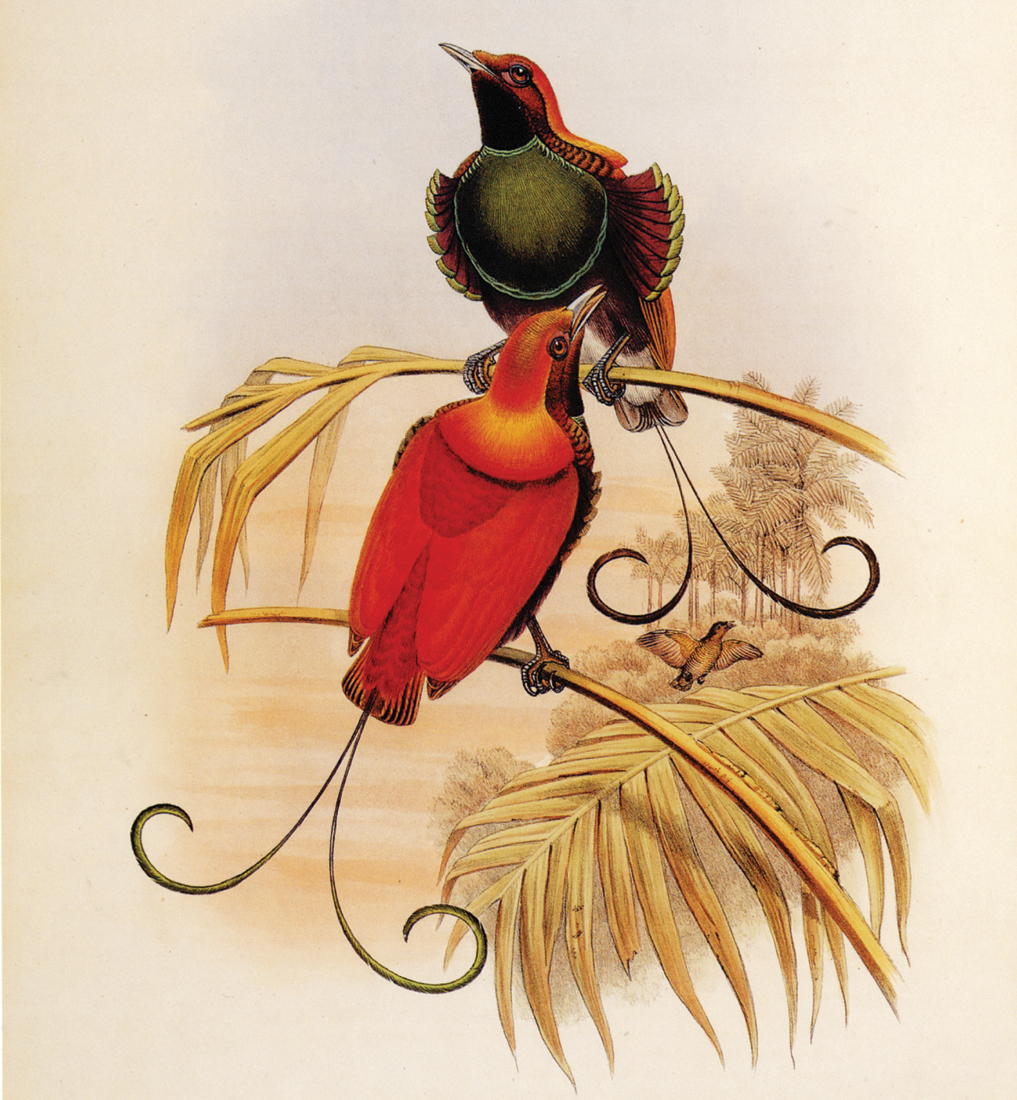

Rhipidornis gulielmi tertii. A hybrid between the King and the Magnificent. William Hart and John Gould. Hand-coloured lithograph from Gould’s Birds of New Guinea (1875–88).

Although hybridisation is not uncommon among birds of paradise, it is rather strange to find that the King Bird sometimes produces crosses with the Magnificent. This surprise is not because of any distance in their relationship to one another; clearly these are very closely related species. What makes it curious is the very considerable difference in the displays that the two species perform. With the male of one kind dancing in the trees and that of the other on the ground in his own specially prepared court, it might fairly be expected that this would present a bar to inter-specific mating. Perhaps it simply shows the sheer power of the two different displays, and indicates that in the right circumstances they are strong enough to attract females of entirely the wrong sort. The females themselves are so similar in appearance that the males may neither know nor care about any subtle difference!

The hybrids produced might be described as avian jewels with plumage showing clear elements of the feathers of both parents. It would be interesting to know whether they result from the visit of a female King to the ground court of a male Magnificent or whether the cross comes about when a female Magnificent flies upwards to the branch a male King occupies. Unfortunately, there is no answer to this little mystery, and perhaps there never will be. More than 20 specimens – all collected by Papuan hunters – can be counted in the world’s museums, but these little hybrids have never been seen alive by ornithologists, and obviously they result from occurrences that are comparatively rare. The first specimens arrived in Europe during the 1870s, and, their hybrid origin not being realised, they were described as representatives of a new species. In accordance with the fashion of the time they were named after one of the crowned heads of Europe, and the monarch chosen as the recipient of the honour was the then King of Holland, William III (1817–90). The Latinisation of his name must be one of the most splendid sounding of all scientific names – Rhipidornis gulielmi tertii. It seems almost a shame that because the specimens are hybrids the name no longer has any scientific validity and is now entirely redundant.

There is, nonetheless, one extreme, and this time legitimate, variation on the basic pattern of the King and the Magnificent. On the islands of Waigeo and Batanta, off New Guinea’s western end, a Cicinnurus species has evolved with a really unusual adornment – an almost featherless scalp coloured light blue. A specimen reached Europe in 1849 and was acquired by an English ornithologist, Edward Wilson (1808–88), who presented it to Philadelphia’s Academy of Natural Sciences. There, a description was published by John Cassin (1813–69), who named the bird after Wilson in recognition of his gift. Today it is still usually known as Wilson’s Bird of Paradise. But not scientifically. The preserved individual had been seen by Charles Lucien Bonaparte (1803–57), a nephew of the Emperor Napoleon. Grabbing the chance of naming a bird of paradise, he rushed his own description into print, just beating Cassin’s in terms of chronology, and thus claiming priority. Despite his grand title of Prince of Canino and Musignano, something of the old revolutionary zeal still burned in Bonaparte’s veins. Stating that he cared nothing for any ruler in the world, and directing a sneer at all those who named these exotic species in honour of the royal houses of Europe, he called the new discovery respublica – the Republican Bird of Paradise.

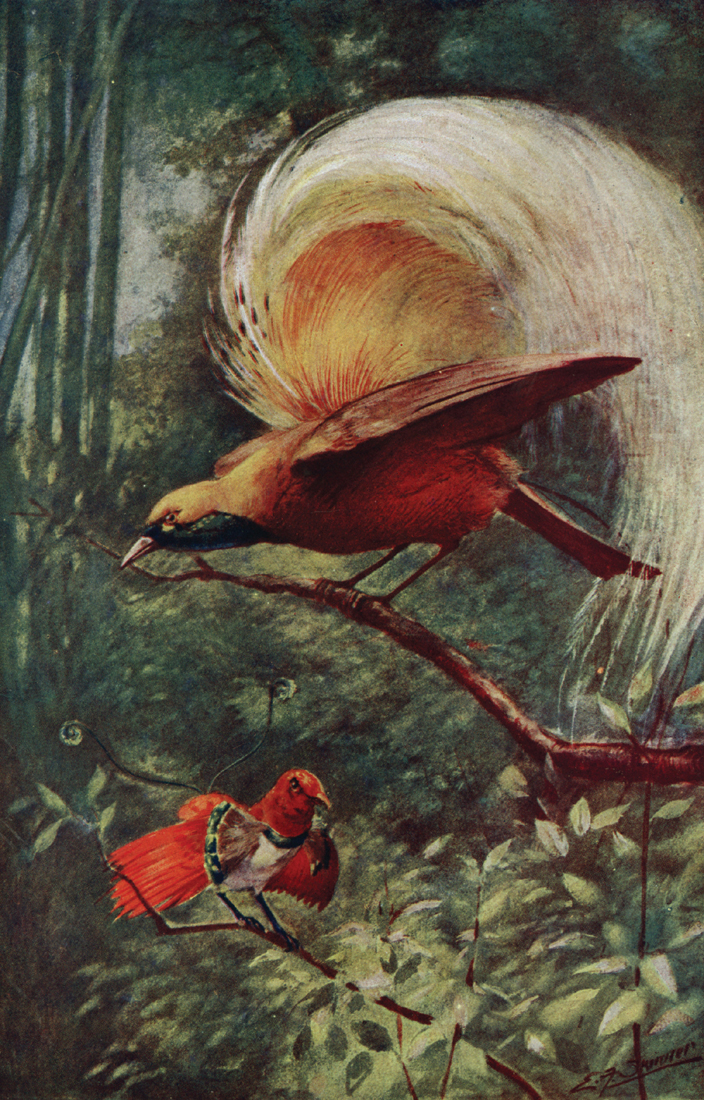

A male Lesser Bird of Paradise showing his plumes to a male King. In reality it is extremely unlikely that the two species would have display perches so close to one another. E. F. Skinner. Medium, date, size and whereabouts unknown.

Wilson’s Bird of Paradise. Carel Brest van Kempen, 2009. Acrylic on board, 15 cm × 22 cm (6 in × 9 in). Bringing the painting of birds of paradise into the age of the internet, the artist released a free stop-frame video showing many stages in the painting of this picture. Courtesy of the artist.

Two images of Wilson’s Bird of Paradise, an early one and one that is more recent.

Raymond Ching, 1976 (detail). Watercolour, 65 cm × 50 cm (26 in × 20 in). Private collection.

An engraving by J. G. Keulemans from Francis Guillimard’s Cruise of the Marchesa (1886).

It had taken two and a half centuries, but no longer were birds of the genus Cicinnurus the exclusive preserve of Habsburg emperors and their descendants. They had been given to The People.