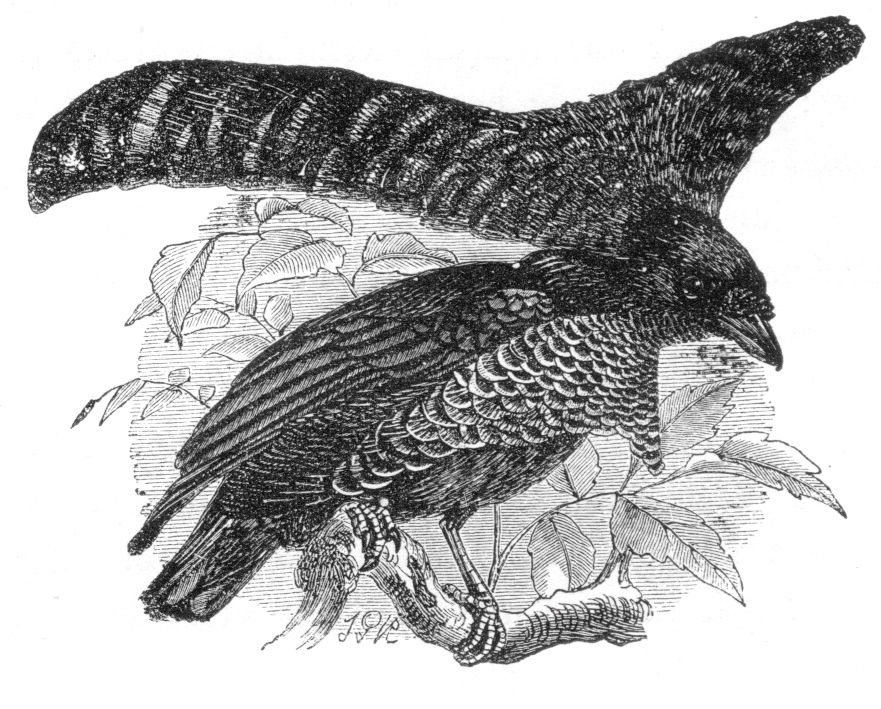

Male Superb Birds of Paradise with a female (detail). Hand-coloured lithograph by Joseph Wolf and Joseph Smit from D. G. Elliot’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae (1873).

Male Superb Birds of Paradise with a female (detail). Hand-coloured lithograph by Joseph Wolf and Joseph Smit from D. G. Elliot’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae (1873).

Male Superb Birds of Paradise with a female. Hand-coloured lithograph by Joseph Wolf and Joseph Smit from D. G. Elliot’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae (1873).

Genus Lophorina

I had reached the banks of the Sepik River. There seemed no possible way to get over it. It was broad and turbulent and full of crocodiles. I had my boys build a bamboo raft. When it was done, we put all of my bird of paradise carcases, preserved in salt, on board. I packed everything else I owned: money, guns, binoculars, rolled tobacco, waxed matches, equipment, gear. We shoved off and headed towards the rapids below us, and the flats just beyond that… we went along miraculously for a time… when we ran onto a pinnacle of rocks. The crash split the raft apart. All of us went into the water – my six Kanakas and I – and we were rushed over boiling falls. We landed on the flats – but minus everything. All of it was washed away, birds of paradise, feathers, plumage, salt and all.

Surprisingly, perhaps, this passage comes from My Wicked, Wicked Ways (1960), the memoirs of Errol Flynn (1909–59). The great screen swashbuckler had been a real-life adventurer before chancing on Hollywood stardom, and had spent several years drifting around the South Seas in search of fortune. One of his schemes – doomed like the rest to ultimate failure – was to make money from the plume trade. The scheme failed, partly from his own impetuous nature, but mostly because he was too late. As far as the western world was concerned, the trade in plumes was fast drawing to its close. Throughout the nineteenth century it had assumed an importance that is difficult to appreciate today, but more austere fashions were now ruling the day, and glamorous ladies no longer wished to decorate their bodies and clothes with such items.

But before the western world ever became involved, this trade had been flourishing for centuries, perhaps even for thousands of years. It began, presumably, when Papuan tribesmen first realised that the feathers of the beautiful birds they saw in the trees and sometimes killed for food could be fashioned into ornaments. By carefully skinning the bird (instead of just ripping it apart for food), then scraping the skin’s inside to remove any lingering scraps of meat, the whole thing would stay intact, feathers and all. If the legs and wings (from which it was difficult to extract the remaining meat) were cut off, the object that remained was relatively immune to insect attack, particularly if the insides were gently smoked. And if moths or other insects did eventually attack – well, a fresh specimen could always be obtained!

Sooner or later a system of exchange and trade sprang up, and plumes from one part of the island were passed along from hand to hand – sometimes for hundreds of kilometres – until they reached a place where the birds they came from were entirely unfamiliar. Small native trading posts sprang up around the coasts, and in time those at the western end of New Guinea were visited by Malayan, Moluccan and Chinese merchants, probably hunting for spices, gold, slaves – anything from which they could make a profit. Now, instead of being taken distances of hundreds of kilometres, the dried skins passed along ancient trade routes and ended up thousands of kilometres from their place of origin. The kings of Nepal wore paradise bird plumes in their coronation hats and the rulers of the Spice Islands gave them as gifts to favoured visitors. And so it was that bird of paradise skins eventually arrived in the western world.

The importance and economic power that the plume trade assumed during the nineteenth century and on into the early years of the twentieth seems particularly peculiar today. Literally millions of suitable birds were slaughtered and exported from their places of origin to the great fashion houses and milliners of London, Paris, Milan or New York. Of course, not all of these were birds of paradise but many of them were, and the trade carried on and on. Particularly high prices were paid for the skins of unusual birds. Best of all would be one that no-one had seen before, and dealers would sort through the bales of feathered skins looking eagerly for such things. And so did collectors interested in the birds from a scientific point of view.

Maria Christina de Bourbon, of the Two Sicilies, Queen of Spain (1806–78), with a hat made from the feathered skin of a Lesser Bird of Paradise. Vincent Lopez Portana, c.1830. Oils on canvas, 96 cm × 75 cm (39 in × 30 in). Museo del Prado, Madrid.

The plume birds, naturally, were much sought after, both by European traders and by New Guinea tribesmen. These native peoples were also particularly attracted to the long tail feathers of the birds we now know as Astrapias. A parrot with bright red feathers, Pesquet’s Parrot (Psittrichas fulgidus), was in great demand, as were the strange head wires from the species that the western world calls the King of Saxony’s Bird of Paradise. All of these items still commonly feature in the headdresses worn by tribesmen for their dances and rituals.

Another great favourite is the triangular fan of feathers – blue in some lights, turquoise or even green in others – that form a seemingly metallic breast shield on a small black bird that occurs over much of New Guinea. This striking fan of feathers, when stolen from the bird itself, often forms a centre piece to the ceremonial headdresses the native Papuan peoples wear, and it comes from male individuals of a species that, because of its intense beauty, is known as the Superb Bird of Paradise.

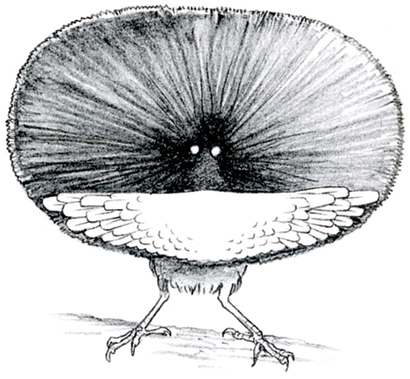

The breast shield, so prized by the natives, is not the only remarkable plumage feature of this species. Adult males have an adornment on the upper back every bit as spectacular – a great cloak of long and soft black feathers that can be raised and lowered at will, or spread like a cape. What the male bird actually does with this cape at the height of its display is even more amazing. It is spread simultaneously with the breast shield so that in conjunction the two form a rather ovoid circle framing what seem to be the bird’s eyes. But these aren’t actually the eyes at all. They are two white patches of light refracting from raised feathers on the forehead, and the eyes themselves peer out from just beneath them.

Just as the display of the Six-wired birds has an almost other-worldly effect, so too does the performance of the Superb. Yet this time it has an almost hypnotic air. The white patches that seem to be eyes stare out with blind but piercing intensity, almost as if some sinister spell is about to be cast. And in a sense, of course, it is.

This is a bird of the mountains, but because it is widespread and common, and also because it was so popular as a trade item with the native peoples, it came to the attention of the western world earlier than many other highland species. During the first half of the eighteenth century, as trade routes to Europe became more established and birds from the mountains became available to merchants, several hitherto unknown birds of paradise came to light, the Black Sicklebill, the Arfak Astrapia and the Superb, among them. It is difficult to determine which came first. A black bird seemingly referable to the Superb is described in a book on the history of the Dutch East Indies Company called Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indien (1724–26). Written by a certain François Valentijn (1666–1727), it contains references to several birds of paradise. The description that probably applies to the Superb is vague and may possibly refer to another species, but what is certain is the fact that specimens became available to European artists within a few decades of Valentijn’s writing.

The male Superb Bird of Paradise in display, imagined by W. S. Coleman. This engraving was produced for the 1872 issue of J. G. Wood’s Illustrated Natural History, a work that occurs in many editions through the last decades of the nineteenth century. Like other artists before and after him, Coleman was trying to make sense of the bird’s extraordinary features.

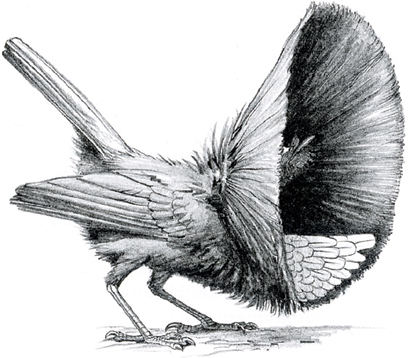

The difficulty of Coleman’s task is made clear in this drawing by the Australian artist William Cooper (c.1990), which accurately shows the fantastic posture assumed by male birds during display. Like other artists of his time, Coleman never saw the bird in life so he couldn’t have imagined it looking like this. Had he produced such a drawing, there is little doubt that he would have been laughed at.

L’oiseau de Paradis à gorge violette surnomme le Superbe. Engraving from Pierre Sonnerat’s Voyage à la Nouvelle-Guinée (1776).

Oiseau de Paradis de la Nouvelle-Guinée dit le Superbe. Coloured engraving by François Nicolas Martinet from E. L. Daubenton’s Planches Enluminée d’Histoire Naturelle (1765–81).

Male Superb Bird. A late nineteenth-century engraving by J. G. Keulemans.

Male Superb Bird. Coloured engraving by Jean-Gabriel Prêtre from René Lesson’s Histoire Naturelle des Oiseaux de Paradis et des Epimaques (1834–35).

Male Superb Bird. John Latham, c.1780. Watercolour, 15 cm × 12 cm (6 in × 5 in). The Natural History Museum, London. Latham clearly based this painting on the engraving in Sonnerat’s book although he slimmed down his subject and left out the tiny bird that had been seized as prey.

These first pictures were wildly inaccurate, however. Among them is one by François Nicolas Martinet (1731–1800). He produced a coloured engraving for Planches Enluminée d’Histoire Naturelle (1765–81), a collection of plates assembled by E. L. Daubenton (1716–99) as an accompaniment to the famous Histoire Naturelle by George-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (1707–88). The picture is decorative, rather than informative.

In terms of the actual shape of the bird, the picture given by Pierre Sonnerat (1748–1814) in his book Voyage à la Nouvelle-Guinée (1776) is little better, and he makes a fundamental mistake that is extremely misleading. His bird has caught a tiny passerine in its talons, which not only makes the Superb look gigantic, but also implies that it is predatory. The English ornithologist John Latham (1740–1837) noticed this little detail and took it at face value. As late as 1822, in the third tome of his monumental ten-volume ornithological work, A General History of Birds (1821–28), he states, ‘In Sonnerat’s figure a small bird is seen in the claws, from which we may infer that it is a rapacious species.’ It is not. It feeds on fruit and insects, and its diet does not include small birds.

Two male Superb Birds of Paradise with a female. Hand-coloured lithograph by William Hart from R. Bowdler Sharpe’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae (1891–98).

Even the great ornithological illustrators of the last half of the nineteenth century had difficulty producing pictures that revealed the bird’s spectacular nature and yet remained true to life. The interesting and the dramatic they could manage (as in the lithograph by Wolf – or the black-and-white engraving by J. G. Keulemans on the facing page), but none of their painted or drawn images is wholly realistic. This is certainly due more to the bird’s curiously contradictory features – modest on the one hand, extravagant on the other – than to any inadequacy on the part of the artists.

It wasn’t until the last quarter of the twentieth century that the true spirit of the male bird was actually captured. A remarkable series of pencil drawings by the Australian artist William Cooper shows exactly what this bird does, and although the drawings depict the more extreme attitudes that individuals adopt, yet they still remain entirely persuasive images of living creatures.

The Superb certainly has various characteristics in common with some other birds of paradise (black feathers, metallic breast shield, shoulder cape), but there are no species that it can be particularly associated with, and taxonomists place it in a genus by itself.

One of a series of pencil drawings by William Cooper (c.1990), showing the postures assumed by male Superb Birds of Paradise during display.