Wallace’s Standardwing Bird of Paradise, two males and a female (detail). Hand-coloured lithograph by Henry Constantine Richter from John Gould’s Birds of Australia (1840–69).

Wallace’s Standardwing Bird of Paradise, two males and a female (detail). Hand-coloured lithograph by Henry Constantine Richter from John Gould’s Birds of Australia (1840–69).

Genus Semioptera, Genus Pteridophora & Genus Astrapia

By the middle of the nineteenth century, the bird of paradise family was fairly well known. In Europe, naturalists, poring over the feathered skins in their studies and museums, had identified nearly all the genera. In Indonesia, Alfred Russel Wallace had, for the first time, observed one of the family displaying in the wild and had published a description of the spectacle in London’s Annals and Magazine of Natural History. But one major discovery was still to come and it was, once again, Wallace who made it.

In October 1858, he left his base in Ternate, a small island in the Moluccas, and set off to investigate Batchian (now spelt Bacan), another island in the archipelago 160 km (100 miles) to the south. He had no certain idea of what he might find there, but he can hardly have hoped to see any birds of paradise since New Guinea, the family’s main home, lay 320 km (200 miles) miles away farther east.

When he arrived in Bacan, the Sultan hospitably suggested that he stay in a house in the village reserved for distinguished visitors. Wallace declined the offer. He had now been away from Britain for over four years, living in open-frame thatched huts, and a house with ceilings didn’t suit him. As he pointed out in his book, The Malay Archipelago, without access to the rafters he would have nowhere to hang things. Worse still, the Sultan’s guesthouse stood in the middle of the village. So Wallace asked for, and was given, a simple hut on the edge of the forest.

A painting produced during the 1950s showing how the artist, Victor Evstafieff, imagined that Alfred Russel Wallace might have looked 100 years earlier when collecting birds on the Aru Islands, New Guinea. The birds on the table are two male King Birds of Paradise. Oils on canvas. Down House, Kent.

The day after he arrived, he and his Malay assistant, Ali, set out to make a preliminary survey, Ali going one way, Wallace another. When they met that evening on their return, Ali showed him what he had collected. Wallace was astounded and wrote:

‘I saw a bird with a mass of splendid green feathers on its breast, elongated into two glittering tufts; but, what I could not understand, was a pair of long white feathers which stuck straight out from each shoulder. Ali assured me that the bird stuck them out this way itself when fluttering its wings and said that they had remained so without his touching them. I now saw that I had got a great prize, no less than a completely new form of the Bird of Paradise, differing most remarkably from every other known bird.’

Male Wallace Standardwing. Walter Weber, c.1950. Oils on board, size unknown. The caption for the magazine article which this painting once accompanied reads, ‘A Bird to Make you Rub your Eyes’.

It was about the size of a jay. Its huge triangular breast shield of iridescent green was certainly beautiful, but the two white feathers projecting from each wing were truly extraordinary. Wallace called them ‘standards’ since that term was already used by ornithologists for a pair of disproportionately long feathers, one on each wing, carried by a species of African nightjar. But these were significantly different, for whereas the nightjar’s standards trailed behind the bird in flight, those of this new bird of paradise were each separately muscled, as Wallace discovered when he dissected one of the specimens. He knew, therefore, that the bird was capable of moving them independently, just as Ali had said.

After this discovery, he continued on to the neighbouring and larger island of Halmahera and there he found another population of this extraordinary bird.

Thrilled by these discoveries, on 29 October 1858, he wrote an excited letter, replete with underlinings and exclamation marks, to Samuel Stevens (1817–99) his agent in London. “I have already the finest and most wonderful bird in the island. I have a good mind to keep it a secret but I cannot resist telling you. I have a new bird of paradise! of a new genus!! quite unlike anything yet known, very curious and handsome!!!”

Stevens sent this letter, together with Wallace’s rough sketch of the bird, to the Zoological Society of London, and in March 1859 it was read out at the Society’s meeting. George Gray (1808–72), the British Museum ornithologist, supplied a written note proposing that this wonderful bird should be named, in honour of its discoverer, Paradisaea wallacei.

By June, Wallace’s specimens themselves had reached London and were duly displayed at the next meeting of the Zoological Society by John Gould, who was by now a well-respected avian taxonomist. He suggested that they were so extraordinary they should be given a genus of their own and proposed that Paradisaea in their name should be changed to Semioptera, a word derived from the Greek meaning roughly ‘standardwing’.

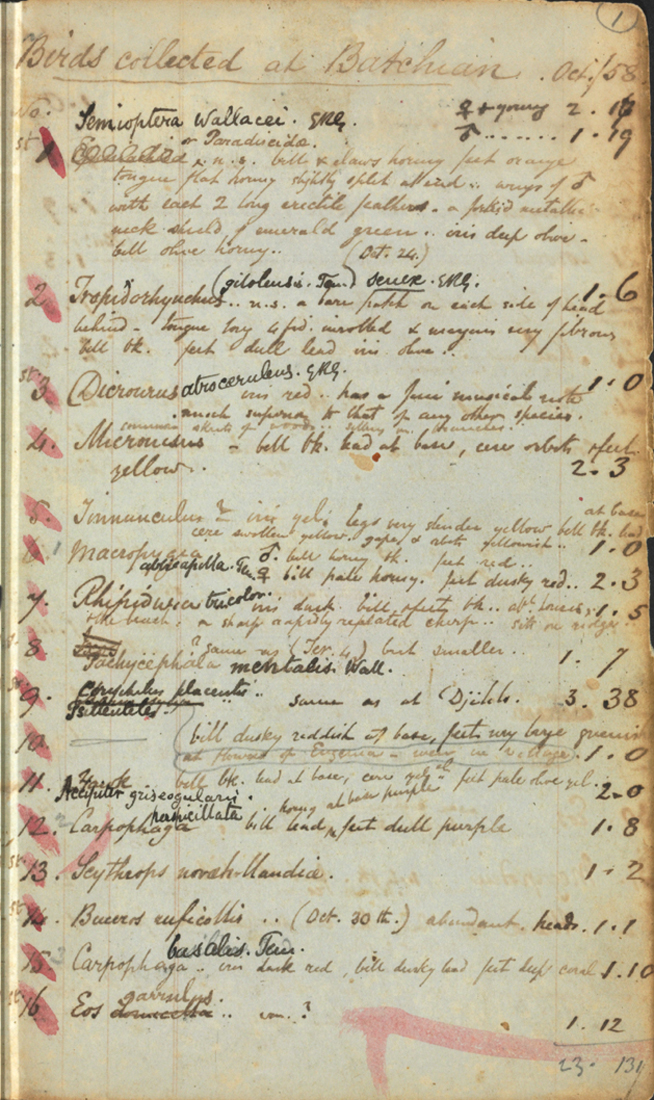

A page from the notebook in which Wallace listed the specimens he collected while at Batchian (Bacan) in 1858. A later hand, that of G. R. Gray, then in charge of the bird collection in the British Museum, has inserted the newly coined Latin name for the Standardwing, Semioptera wallacei, and initialled his addition. This notebook is in the collection of the Natural History Museum, London.

Detail from the same page showing the section that lists the Standardwing.

Then he went further. He questioned whether the bird was really a bird of paradise at all. Perhaps, he suggested, it was allied to the riflebirds which, conveniently for Gould and the publication he was working on, lived in Australia as well as New Guinea.

Gould was eager to publish the discovery as soon as possible. He had just released the first two parts of a Supplement to his Birds of Australia. So the following September, in spite of the fact that the Standardwing lived several hundred kilometres away from the continent in the supplement’s title, a plate of the bird duly appeared in the third part. It was drawn by Henry Constantine Richter (1821–1902), an accomplished ornithological illustrator who was one of Gould’s regular artists.

Judging from the plate, neither Richter nor Gould, who normally supplied rough layouts of the plates he commissioned, truly believed that the birds could erect their extraordinary standards, for although Gould regularly showed birds in what he supposed to be their display postures, the Standardwing’s white wing plumes are shown hanging somewhat limply by the bird’s side. Even John Gerrard Keulemans (1842–1912), when he supplied the illustration of the bird for Wallace’s own book in 1869, shows the most prominent individual with its standards at what might be described as half-cock.

Wallace’s Standardwing Bird of Paradise, two males and a female. Hand-coloured lithograph by William Hart from R. Bowdler Sharpe’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae (1891–98).

Wallace’s Standardwing Bird of Paradise, male and female. John Gould, c.1860. Watercolour, 15 cm × 13 cm (6 in × 5 in). This rudimentary unsigned watercolour has a Gould family provenance. It seems to be a provisional layout for the two upper birds in the lithograph shown above (which, interestingly, was not published until some years after Gould’s death). The image of the male may in turn be partly based on one of the lower birds in an earlier Gould-inspired picture. Private collection.

The species’ island homes, Bacan and Halmahera, remained little explored by Europeans until well into the twentieth century, and for some time ornithologists were uncertain as to whether the species still survived. But in 1927, a British animal collector, Walter Goodfellow (1866–1953), not only rediscovered the bird on Halmahera, but wrote a full description of its display.

Wallace’s Standardwing Bird of Paradise, two males and a female. Hand-coloured lithograph by Henry Constantine Richter from John Gould’s Birds of Australia (1840–69).

The birds assemble early in the morning, in the tops of low trees in groups of at least thirty or forty. As dawn breaks they start a more or less constant chatter of calls among themselves while excitedly fluttering back and forth, erecting their green cravats, beating their wings and sometimes, as the calls mount to a crescendo, swivelling on a branch to hang upside down beneath it.

But the males also have another display trick all of their own that has only recently been described. While singing excitedly, one will suddenly leap vertically upwards. Flapping vigorously, he rises for 6 metres (20 ft) or so in the air and then suddenly stops beating his wings and, holding them outstretched, floats downwards headfirst, so that the rush of air makes his white standards vibrate and become a white blur alongside each wing until eventually he lands on the perch from which he took off – or very close by.

This extraordinary display is not the only thing that sets the Standardwing apart from other birds of paradise. It is also one of only two species living in the Moluccas (the Paradise Crow, a species in which males and females are similar, is the other), an archipelago far beyond the recognised zoological limits of the family headquarters in New Guinea, and its offshore islands.

Is it truly a member of the Paradiseidae? Or was Wallace led to categorise it as such by his own enthusiasm for the family? Gould’s suggestion that it might be related to riflebirds seems not very revolutionary today, for now riflebirds themselves have been recognised as members of the Paradiseidae.

Later suggestions have been more radical. Some ornithologists have pointed out that were it not for its standards and emerald breast shield, the Standardwing would look very like a friarbird, a group that has members not only all over New Guinea but in most parts of Australia. It has much the same sharp down-curved somewhat aggressive-looking beak. Perhaps DNA will eventually reveal the correct taxonomic placing of the bird, but meanwhile it remains a bird of paradise. It would be a pity indeed to remove the species that bears Wallace’s name from the group that he loved the most.

Wallace’s Standardwing Bird of Paradise, two males and a female. Engraving by John Gerrard Keulemans from A. R. Wallace’s The Malay Archipelago (1869).

King of Saxony’s Bird of Paradise, male. William Matthew Hart, c.1894. Watercolour, 50 cm × 38 cm (20 in × 15 in). Hart based the plate that he produced for R. Bowdler Sharpe’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae (1891–98) on this painting. Private collection.

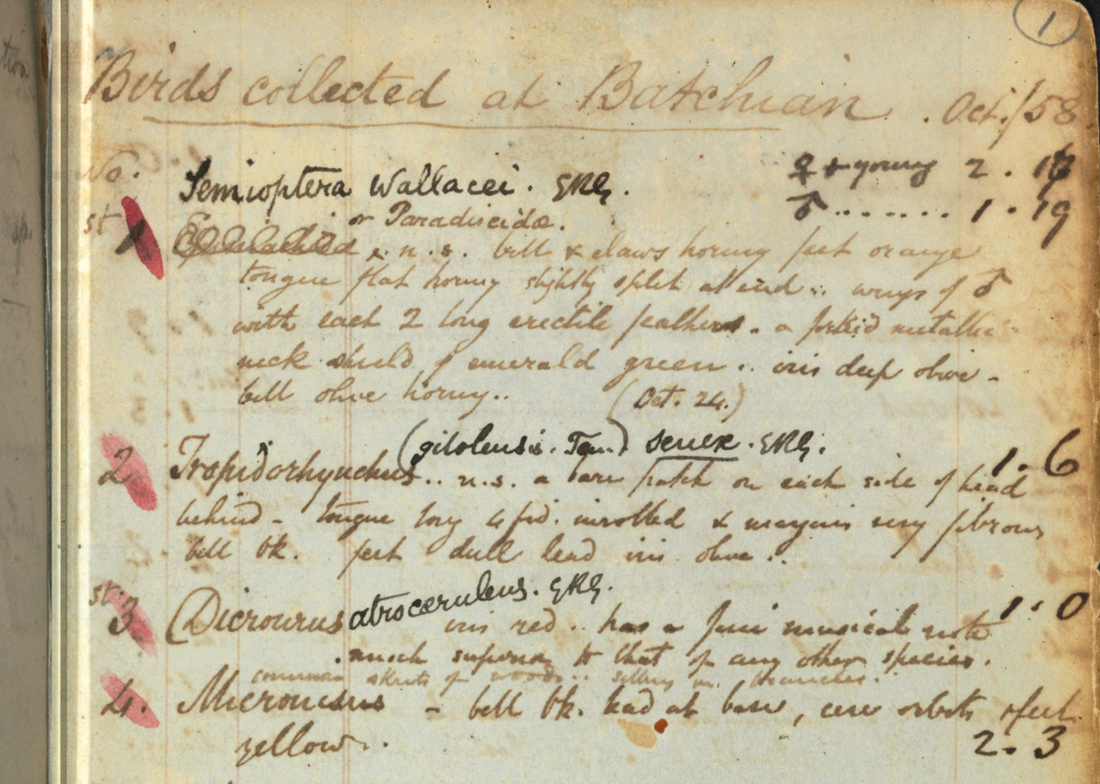

King of Saxony’s Bird of Paradise, study of a male in various stages of display. W. T. Cooper, c.1976. Pencil, 48 cm × 35 cm (19 in × 14 in). Private collection.

In the decades that followed, more species of the long-established genera were found – more Six-wireds, more Sicklebills, even more birds of the classic plumed kind. Goldie’s Bird (Paradisaea decora), which has plumes of a rather richer red than those of Count Raggi’s bird, was discovered in 1883 on tiny islands off the eastern tip of the main island, then part of the British Empire, and five years later another variant was found on the Huon Peninsula, with plumes that, though yellow at the base, are for most of their length a gauzy white. That part of New Guinea was at the time claimed by Germany, and in consequence it was named the Emperor of Germany’s Bird (Paradisaea guilielmi).

The Stitchbird of New Zealand, male and female, a species that bears a surprising resemblance to the King of Saxony’s Bird of Paradise. Chromolithograph after a painting by J. G. Keulemans from Walter Buller’s A History of the Birds of New Zealand (1887–88).

Then in 1894 came a sensation – a species that looked rather like the Stitchbird of New Zealand. But it had a kind of decoration not only unlike that of any other bird of paradise but one unparalleled in the whole of the world of birds. Adolf Bernard Meyer (1840–1911), the Director of the Dresden Museum who was instrumental in the discovery of many birds of paradise, first described the species from a specimen collected in the still largely unexplored mountain ranges of central New Guinea. Meyer loyally named it Pteridophora alberti after his king. In English it is known as the King of Saxony’s Bird of Paradise.

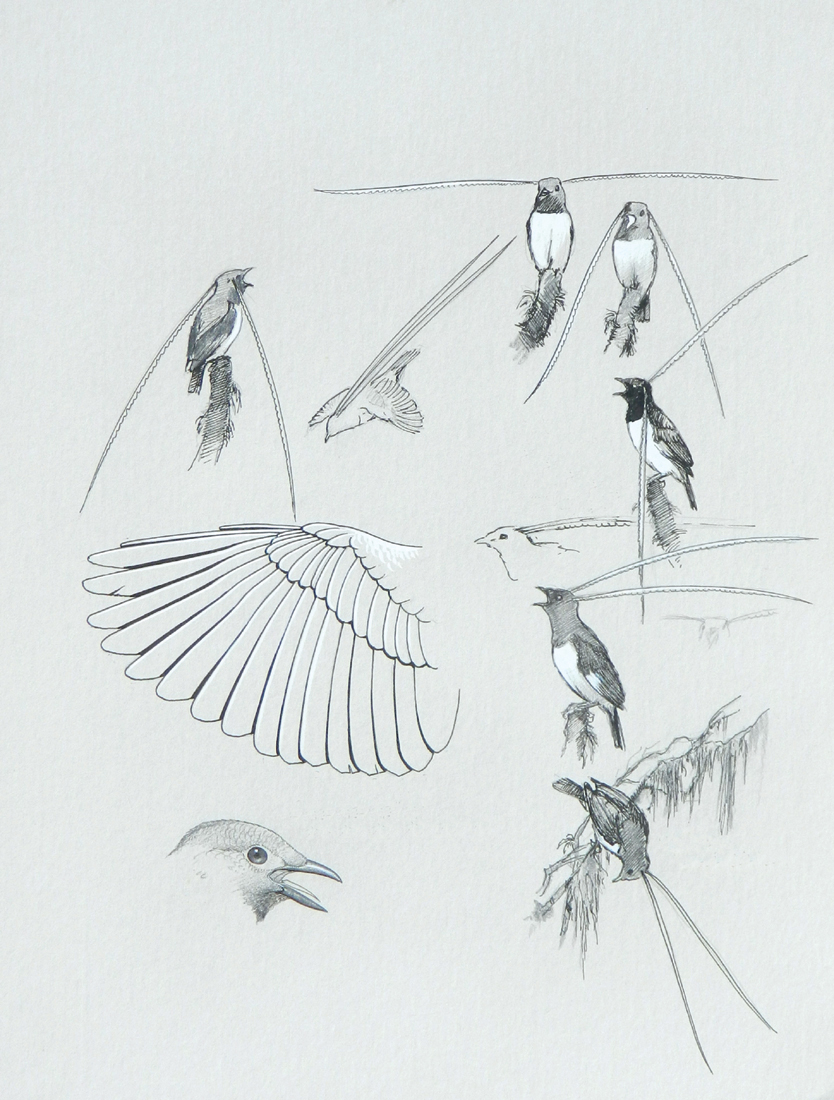

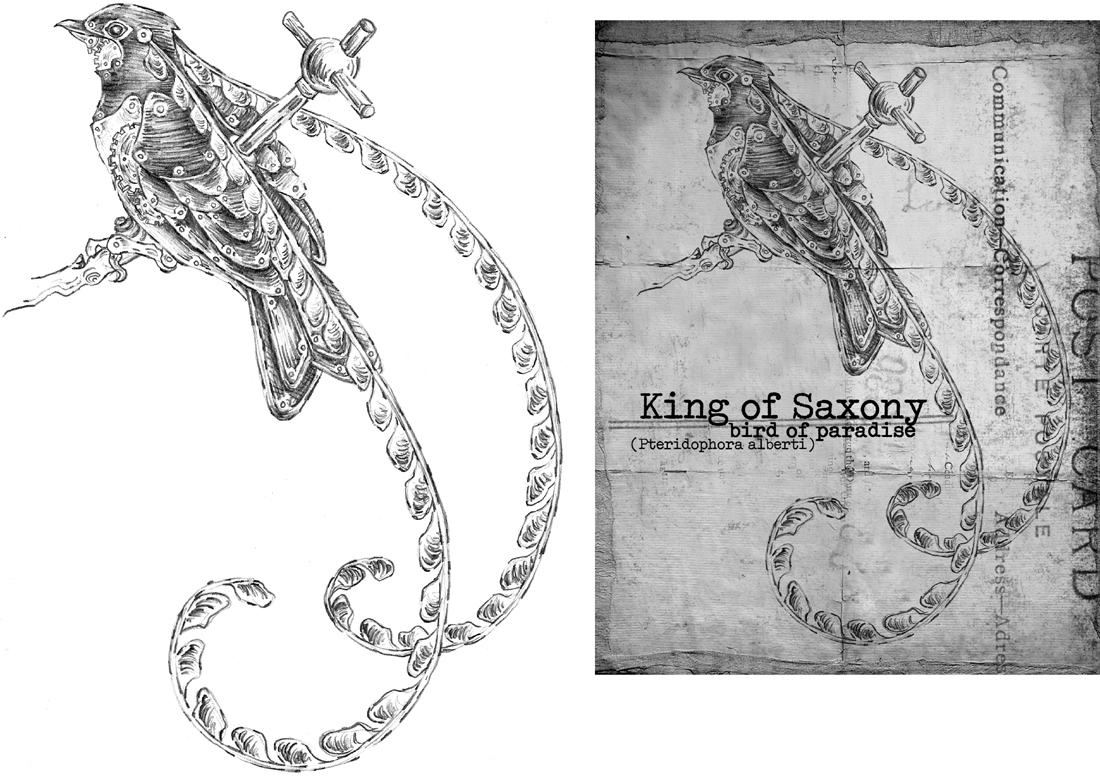

A fanciful interpretation of a male King of Saxony’s Bird of Paradise by Greek artist Vaso Kafkoula, from a series of bird illustrations called ‘Clockwork Creatures’. Mixed media, c.2009. By kind permission of the artist and vasodelirium.blogspot.com

It is about the same size as a Six-wired bird and the female looks not unlike a female of that genus. But the male is astoundingly different. Two extraordinary decorations sprout from the back of his neck. Though they are clearly feathers, it would be hard to recognise them as such if they were found unattached to a bird. They are over three times as long as his body. The quill lacks any barbs of the normal kind. One side, in fact, is totally bare. The other carries a line of thirty to forty rectangular platelets like tiny flags. Their underside is a dull grey, but above they are a wonderful pearly blue with a surface more like that of a shell than a feather. So stunningly distinctive are these ornaments that Papuans regularly use them to decorate their headdresses.

A displaying male exploits these remarkable ornaments to the full. He starts by singing a strange hissing song high up on the forest canopy. Then he comes down to his regular display perch – the bottom curve of a looped hanging liana. Still hissing and squeaking, he flexes his legs repeatedly and vigorously. Soon he is bouncing up and down on his springy vine with all the determined enthusiasm of a child on a playground swing. By this time, a female may have arrived and she perches a little above him on the vine. She too appears to be enjoying the ride. To begin with he holds his head plumes as he normally does, pointing horizontally over his back and extending far beyond his tail so that as he bounces they sway gracefully along their length. But soon he begins to move them, each independently, if he so wishes. Sometimes he holds them at right angles to his head. Sometimes he swings one vertically upwards while holding the other vertically downwards. The female stays on the vine a short distance above him, until, with plumes a-swirling, he hops with increasing speed up the vertical vine and the pair copulate.

The first illustration of the male Ribbon-tail Bird of Paradise, with and without its long tail feathers. Lilian Medland. Watercolour reproduced in The Australian Zoologist (1939). Whereabouts and size of original unknown.

The discovery of this almost unbelievable bird came at the very end of the nineteenth century, and it might have seemed, as the twentieth century dawned, that the bird of paradise family had now been fully revealed. But there was just one more glory to come.

It took some time to appear. After the Great War of 1914–18, Germany lost control of its territory in the island, and Australia, which had taken over British responsibilities, administered all the eastern half. Much of the interior was still unexplored.

In 1935, a young and extremely tough patrol officer, Jack Hides (1906–38), set off to explore the unknown mountains between the Strickland and Purari rivers. He took with him an Irish-Australian assistant, ten armed New Guinea policemen, and 28 locally recruited carriers. It was the last major exploring expedition in Australian New Guinea that had no radio or aerial support, and it lasted six months. They took steel axe-heads with them to use in bartering for food, but the people they encountered, who had never seen Europeans before, were not interested in such things. They preferred their stone axes. There were fights and ambushes. Lives were lost on both sides. Halfway through, after making camp at an altitude of 2,250 m (7,500 ft), Hides climbed a tree to try and see what lay ahead, and work out the best route between the mountain peaks confronting him. Later, he wrote:

as I stood in the branches gazing at the rock- and heather-covered summit of the peaks in front of us, I noticed pairs of an interesting species of paradise birds flitting through the moss-covered branches of the trees ahead of me. The males had two ivory-white feathers as a tail with which they made flicking noises as they trailed the plumes after them through the air. I did not know of this species so for the information of our ornithological department, I instructed one of the police to shoot a male bird, remove the tail feathers and carefully pack them away.

Exactly what happened to those feathers subsequently is a mystery, but the fact that a possibly unknown species had been discovered came to the notice of Fred Shaw Mayer (1899–1989), a young bird collector working in the island. He started to search for the birds, but although he failed to find a living specimen he did secure a pair of long white feathers that must have belonged to the mystery bird. They had been collected by a missionary who had noticed them in the headdress worn by one of the tribesmen in the Wahgi, the wide valley that runs east to west like a long crease through the central mountain ranges. Shaw Mayer sent them to London where they were examined by one of the ornithologists at the British Museum, Charles Stonor (1912–82). He concluded that they did indeed come from a hitherto unknown species and promptly – perhaps even a little precipitously, since they were the only material evidence he had – published a description of them, attributing them to a new species of Astrapia which he called mayeri. It was also given an English name – the Ribbon-tailed Bird of Paradise.

Meanwhile, another Australian patrol was exploring the mountains between the central Wahgi valley and the Sepik River which drains northeastern New Guinea. At high altitudes they too saw a bird with extremely long white tail plumes, and they collected, not just the tail feathers, but complete specimens which were sent to the Australian Museum in Sydney. Unaware of what was happening in London, the Australian taxonomists also described their bird, and not only gave it a specific name but allocated it to a new genus, Taeniaparadisaea macnicolli. However, since the rules of scientific nomenclature dictate that the first name given is the one that survives, Fred Shaw Mayer, who was one of the most modest and retiring of men, still retains his celebrity.

Ribbon-tail Bird of Paradise, male. Errol Fuller, 1993. Oils on panel, 19 cm × 39 cm (7 ½ in × 15 ½ in). Private collection.

The Ribbon-tail has one of the most limited distributions of all the mainland species. It occurs only in the high moss forest at altitudes of 3,000–3,300 m (10,000–11, 000 ft) on the peaks around Mount Hagen in the very heart of the New Guinea highlands. The sheer length of its great white tail makes it very conspicuous and also prevents it from indulging in complicated gymnastic displays. To attract a mate, the male simply flies back and forth between two relatively close perches, landing each time with a thump and then thrashing its immense tail like an angry cat.

By the time the Ribbon-tail was discovered, Richard Bowdler Sharpe’s celebrated monograph on the family had long since been printed. But the species appears in its full splendour in the 1977 monograph illustrated by William Cooper. In Cooper’s picture a pair of birds are perched on the substantial branch of what is clearly an emergent tree – the male with his long tail catching slightly awkwardly on the bough – feeding on the small fruits that Cooper had actually seen them eating.

For the first time since Aldrovandus portrayed a legless bird of paradise floating in heaven, four hundred years earlier, the birds were shown to the world by an artist who had seen them alive in the wild.