Fear of Favoritism, or Does It Have to Be Lonely at the Top?

How to Support Our Leaders Having Friends

“I’ve never been lonelier,” Monica wrote me after a recent promotion at her financial institution. “I have more decisions to make than any other time in my career, and yet I feel like I can’t talk it out with anyone. . . . Everything is so confidential or hard to explain. Add to that, I’m working longer hours so even my few friendships outside of work have taken a huge hit.”

We frequently talk about how lonely it is “at the top,” and yet we’ve almost resigned ourselves to believing that’s the way it has to be. As a workforce we need to sit with that and inquire whether we really want to create a world where the people who are making the biggest decisions and casting the vision for the rest of us are being expected to do that from a place of disconnection and loneliness.

Not only do they need connection, but the sad reality is that most of them aren’t getting it. Our leaders are lonely. One study a number of years ago suggested that 60 percent of CEOs say they’re lonely and three-fourths of them say it’s hurting their performance.1 Extrapolate that to all managers, supervisors, and leads—and that’s a big chunk of our workforce. If it’s not social loneliness (from lack of interaction), then it’s usually emotional loneliness (lack of closeness) or situational loneliness—triggered by not having people who really get what they are facing. The responsibilities and pressures they face, from themselves and others, makes them at risk of feeling distance between them and those around them.

OUR LEADERS NEED FRIENDS TOO

Our bosses, before they are their role, are humans, who just like us need to feel seen in a safe and satisfying way. They need connection as much, if not more, than the rest of us. The more stress we carry, the more we need supportive relationships to buffer our bodies from that impact. The less time we have for connecting is often a sign that we need it more than ever. Our bosses have a greater likelihood of being happier, connecting with our team more, and giving us more permission to have friends at work when they are also getting their needs met. We benefit from them having meaningful friendships.

One might push back and say, “Yes, well, I want them to care about their teams, but there’s no need for them to be closer to some than others.” Or one might give the traditional response, “Yes, but they can go make friends in mastermind groups or with other people at their level—just not someone who reports to them.” That might work if we were all going to forever stay in the same positions and in the same companies, but as an administrator once told me, upon my asking why he treated all the interns with such respect, “Who knows . . . in ten years you could be my boss.” In many ways it might be less messy to simply do a better job of training everyone on how to develop appropriate and healthy relationships than to ask people to keep switching who they can befriend every time there’s an employment change.

To that point, look at the friendship of Jeff and Omar, who met at work twenty-five years ago when Jeff, who in an entry-level job at a telecommunications company, went into Omar’s office, who was several levels above him at the time, and introduced himself by asking for advice on how to advance his career. Their friendship developed alongside their careers to the point where Jeff eventually reported directly to Omar. It was this “genuine friendship,” he said, that was the hardest to leave a few years later when he accepted a position as COO for a start-up. Was that hard on the friendship? I asked, wondering if Omar had felt disappointed, betrayed, or hurt. “No, he totally understood it was too good of an opportunity to pass up.” And they needn’t have worried because over the years Jeff would work again for Omar at a different company, and at one point when Jeff was CEO at a software company, he recruited his friend to come work for him as VP. Roles completely reversed. And this time he beat me to the punch: “No, it wasn’t hard. We could trust each other, we respected each other, and there was no one else I’d rather have working alongside me.” They eventually started their own consulting company together, but more importantly they have maintained their friendship throughout their careers. Imagine if they had to stop their friendship every time one of them worked for the other.

Unfortunately, that’s all too often what we expect. “I’m all about our employees having close friends at work,” a human resources director for a global media company told me. “But where it gets too messy is if our supervisors try to be friends with their direct reports. That’s where I draw the line.”

ACKNOWLEDGING THE FEARS AND HESITATIONS

What are we afraid of?

All it takes is looking at the answers to “What are your biggest hesitations or fears about workplace friendships?” in general, and we quickly see that not only are three of the top five most popular answers directly related to that boss/employee relationship, but we also see what we’re most afraid of, specifically:

1. Risking favoritism |

42 percent |

2. Betrayal of secrets/information |

38 percent |

3. Needing to fire/reprimand a friend |

37 percent |

4. Maintaining friendship if one becomes boss |

30 percent |

5. Losing the friendship after leaving the job |

29 percent2 |

Those aren’t small things.

But allow me to remind us that drama doesn’t disappear simply by removing the word friendship from our leadership lexicon. It’d be one thing if all three of those risks—the appearance of favoritism, awkwardness around firing others, and transitioning to new reporting roles—were nonexistent in a company without friendship. But a workplace without friendship is hardly safe from these concerns. It’s not a given that our supervisor won’t still overlook our talents just because they have no friends on our team, that being fired by them is less painful if we don’t feel like they care about us, or that reporting to someone we don’t respect is more fun than if our friend were promoted.

Obviously, not a one of us wants to ever feel insecure in our jobs, underappreciated, or confused in our roles. I get that. Without a doubt, if we’re human then we’re prone to worry about not feeling as special as someone else. Double that worry if that someone else is also responsible for helping us earn a living. It makes sense that every insecurity button might get pushed if and when our boss appears to be closer to one of our coworkers.

But what if it’s better relationships for them, not lack of them, that might lead to the stronger communication that is more likely to leave us feeling more seen in safe and satisfying ways?

RECOGNIZING THE BENEFITS AND POSSIBILITIES

I personally have yet to meet any leaders who, because of a meaningful friendship, stop caring about their team, their reputation, or their mission.

We’re all too often setting them up for failure if we expect them not to bond with the people with whom they work. The very nature of their work has them practicing the Three Relationship Requirements regularly with the same people; there’s really no way not to feel closer to each other if they’re committed to being leaders who value the relationships around them. In fact, they’re the ones who are most often scheduling and planning the very “team bonding” activities that we all hope will bring the team together, so it seems unlikely to expect the results to differ for them.

If we ask them not to feel closer to any one person than another, then we’re asking them to only bond up to the level of the weakest relationship on the team. If we blame them for anyone who feels jealous or worried, then we are essentially not only blaming them for getting healthy needs met but also robbing the rest of us from doing the emotional growth that is ours to do. Our insecurities, discomfort, and fears will be there for us to examine and own whether our leaders have friends, or not—and, besides, we don’t solve jealousy by taking something away from someone else.

The truth is that if we can’t trust our leaders to want to still create as healthy of a team as possible, no matter who their friends are, then we have a serious leadership issue we need to address.

But fortunately, almost all of the leaders I interviewed argued that their friendships actually helped them better navigate these very tough scenarios mentioned above.

• In avoiding favoritism: “Because I was so sensitive to not wanting it to appear that I was giving preferential treatment to some of the people I was closer with on the team, I think it made me a better leader, because I ended up giving more one-on-one time to every person on my team. The more I got to know each team member, the better I could articulate their strengths and contributions, and the more they trusted my decisions. As long as they knew they were seen and valued, I never had any problems.”

• In firing a friend: “I felt sick knowing I needed to replace my friend because she simply wasn’t pulling her weight on our team. Of course, I’ve felt that way about every person I’ve ever had to let go. But, interestingly, because of our long-standing friendship, we were able to have a deeper conversation that led to her admitting that she really missed her past life as a dancer and how much she hated working in an office. In some ways, because of our friendship, it felt like I was actually better honoring her by encouraging her to not settle at this job.”

• In evaluating and giving feedback: “I often joke that I wish I could schedule all my friends outside of work to come have ‘employee evaluations’ with me because they are so bonding. I trust the friendship I have with one of my employees more than I do any other friendship in my life because it’s the only friendship where we’ve had to talk about our growth edges, where we want accountability, what boundaries we need to set, and what kind of support we each need from the other. I love knowing we are cheering the development in each other.”

Obviously, those great examples aren’t how it always goes down, but it’s good for our minds to remember the potential and to consider better training our leaders on best practices. For beyond those three common fears, when I surveyed some of those who have loved having friends they report to, or vice versa, I heard all kinds of additional potential benefits too.

We learn from each other. An assistant editor credits her close friendship with her senior editor as the place where she’s learned the most about what it takes to be in a similar role someday: “Seeing behind the scenes has helped prepare me more than anything for the kinds of decisions that must be made and the level of chaos I have to be ready to take on.” But it goes the other way too. Several supervisors shared how much it has helped them to have someone they can trust on their team giving them honest feedback. A hospitality manager said, “It was my friend who was able to tell me how the waitstaff felt more exhausted than inspired by my attempts at leading cheers and getting everyone revved up for their shift. It immediately gave me permission to show up with more authenticity.” Friends at work have a front-row perspective to who we are at work, and where we can grow, in a way that no other spouse, neighbor, or college friend can offer.

We feel less divided in our lives. This benefit—the feeling of support in having at least one friend who is familiar with both their personal and professional worlds—came up quite a bit in interviews. An art director shared how painful it was to lose her mother last year and how meaningful it felt to have at least one person at work knowing how torn up she was about the loss. “I mean, I told my team—so they knew, but it was such an anchoring feeling to have my friend there who really knew just hard it was for me. It made me feel a little less like I was hiding something or trying to pretend it didn’t really matter.” Joseph said something similar, but for him it was sharing the love of fatherhood with his regional coordinator, Bobby. He confided, “I often feel, as a guy, that we’re not supposed to be that devoted to our kids. I rarely talk about my two boys as much as I sometimes want to. So I love that Bobby knows my kids, attends some of their parties, and thinks they’re awesome. It helps me feel like even though I’m one of his sales guys, he also sees me as a father, which means more than I realized.”

We can accomplish big things because of our shared trust. A common theme from those who have worked closely with friends is how much the friendship—because they knew each other’s strengths and trusted each other—led to big things like changing the DNA of a team, coming up with a big idea, starting a new revenue stream, or taking on a challenging deadline. Matt hired one of his best friends to work for him after a frank conversation about what it would look like to supervise him. He concluded, “I honestly couldn’t have created that department without him. It would have taken years to have developed that level of trust with someone else.” When we care deeply for the person we’re working for, or with, we’re both willing to put in more hours, we’re less competitive with our strengths, we feel safer to brainstorm big ideas, and we’re more willing to take on a risk as we feel like we’re not in it alone.

We take things less personally and assume the best more often. The closer we feel to someone, the less defensive we need to feel. We learn that that’s just the way he reacts to stress and it’s not about us, we’re more willing to check our stories out with each other before jumping to conclusions, and we’re less likely to get our feelings hurt when she doesn’t respond in the way we hoped. The more we believe that people have our back and aren’t out to hurt us, the more we are willing to trust their explanations and forgive their mistakes. Linda said, “Working for my friend for three years was the best job ever because we so easily gave each other the benefit of the doubt. It wasn’t until then that I realized not only how much of my other jobs have lacked that but how much energy we spend because of that!”

Hearing some of the testimonies from others makes that clear line we often want to draw between friendship and leadership a little less clear, doesn’t it?

But here’s what hopefully feels a little clearer:

1. Friendships are happening—whether we want them to, or not. Even with our leaders.

2. Avoiding friendships doesn’t automatically avoid the drama, the fears, or the awkward parts of leading people. In fact, it can exacerbate those very things.

3. If friendship at work increases engagement, productivity, enjoyment, and retention—it would be so for leaders too.

The alternative to them bonding more with the people on their team is for them to be emotionally distant from their team and pull away—less authenticity, less positive reinforcement, less reliability. Leadership, above all else, is relationship. We know that trust is the goal, that Vulnerability and honesty are part of the currency, and collaboration is where the magic resides; but none of that happens in a vacuum alone. Our leaders have to be connected to us.

It’s to the benefit of our employees, teams, departments, and organizations that our leaders not just lean into healthy relationships but model them, practice them, and excel at them. And in so doing, they might end up feeling a little more connected to someone else more than they do to us. And that’s okay, isn’t it? We do that too. It’s normal. It doesn’t mean there’s scarcity, that our career won’t progress, or that we’re not appreciated—that’s just our fear whispering. Maybe, just maybe, we can each take a little more responsibility for checking our own fears and jealousies about who our boss is close to and instead try to hold gratitude that they are healthy enough to connect with others, focus on building the healthiest relationship we can with them, and trust that they can still be a good leader to us all.

A phenomenal example is Kimberly, whom I met when I was the keynote speaker at a women’s leadership conference she was hosting for female insurance agency owners. It was clear she had the respect of the hundreds of women in the room. And in her introduction of me I saw glimpses of why they adored her. Flashing photos up on the screen of her with a group of friends, who had all worked for her at some point, she said to everyone in the audience, “This is what I want for you. We can’t do this alone.” I can attest it’s far too few executives who hire a friendship expert to come speak to their leaders, but even fewer still who proudly talk about their own friendships developed from work and share the benefits they’ve experienced. Kimberly gets together with her eight former employees for an annual girls’ trip—they’ve been doing it for almost two decades. I’ve heard so many stories like this. Stories of emotionally intelligent humans forming friendships that extended beyond the lines of their roles.

In the next chapter I am going to teach how all of us can build healthier and more appropriate friendships at work; if you’re a leader who values healthy relationships, it’ll be your responsibility to model those behaviors—including the hard conversations.

And for the rest of us who find ourselves getting fearful about favoritism, let’s take a deep breath and remember that our peace will come not from preventing or begrudging the connections of others but in examining our own feelings and doing the work to build the connections we want.

HOW TO RESPOND WHEN WE FEAR FAVORITISM

Very rarely are our bosses out there trying to make any one of us feel less than appreciated or valued. They may not be trained to be as competent or affirming as we wish they were, but the truth is that they really are doing the best they can with what they have right now. Most of them aren’t waking up thinking, “How can I show preferential treatment to one person today and leave others feeling bad?” On the contrary, in fact, a recent study in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology showed that supervisors are actually more prone to show a bias against their favorites in order to seem impartial.3 (Which isn’t what we want either, but it does show how much our supervisors are trying to be fair.)

But it doesn’t always feel that way.

Roger resented his boss because she appeared so chummy with some of the other women at the loan processing division where they all worked. When I unpacked that with him, he realized that he actually had little desire to stand in her office talking with her like some of his colleagues did; but he was more afraid that by others doing it, his chances of being promoted would be impacted.

That’s a big aha. It’s powerful when we can start with identifying whether we’re “jealous,” which means we fear losing something or someone to someone else, or “envious,” which means someone has something we desire. In Roger’s shoes, some of us might identify that we’re envious—we want to be closer to our boss. But in his case, he didn’t so much want to be her friend as much as he felt jealous because he didn’t want to lose out on a possible promotion. Starting with self-assessment helps us know the best path forward.

If he didn’t realize that soon enough to do something about it, what probably would have affected his chances of being overlooked more than anything would have been that unchecked resentment showing up in passive-aggressive or sabotaging ways in the office. Instead, though, he ended up talking with her and sharing the growth he hoped to experience and asking her what she felt he could do that would best prepare him for that someday promotion. On that track, with her coaching him for growth, he realized he was less threatened by her social interactions.

We picked a favorite stuffed animal when we were toddlers, we have foods we love, and we will enjoy some people more than others. We all have certain people we feel closer to, trust in certain situations more, or feel will be a better fit for a certain project or task. Not only do we not leave our preferences at home when we come to work, that ability to choose one thing over another is what helps us make decisions and do our jobs efficiently. It’s not realistic, or even healthy, to expect those around us not to have “favorites.”

How can I foster my relationship with my boss?

The question here isn’t so much whether our bosses have people they prefer or trust and rely upon as much as whether we’ve developed the healthiest relationship with them that we can.

• Have we been reliable?

• Do they know our strengths?

• Do they feel supported and encouraged by us?

• Have we asked them recently to share with us where they think we have the most room to grow?

• Have we practiced generosity with them—with credit, with praise, and with generous interpretations of their behaviors?

• Have we built trust by admitting when we don’t know something?

• Would they have any reason to believe that we don’t have their best interest at heart?

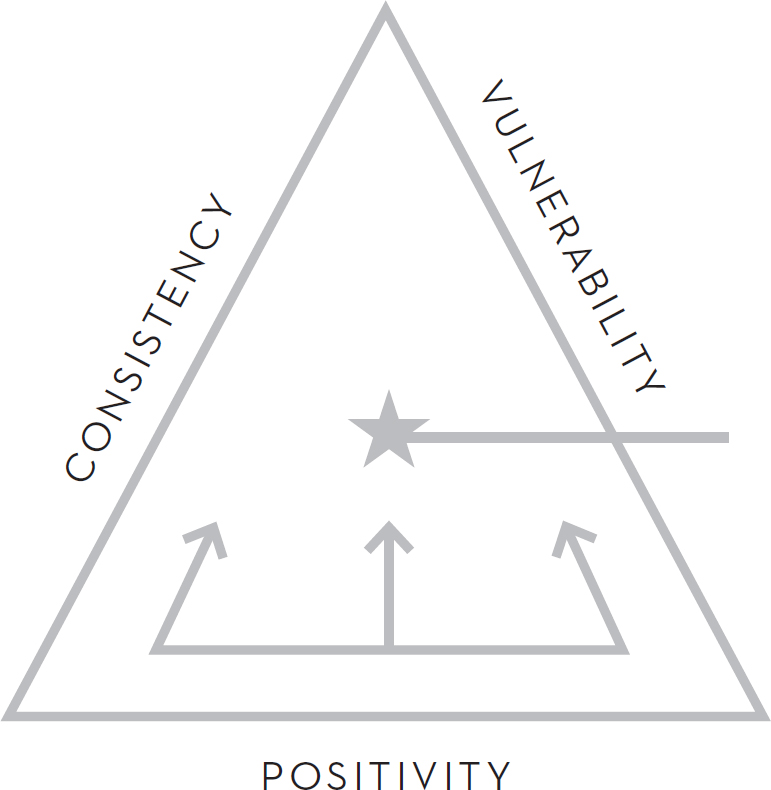

If the answer to any of those questions is no, then it probably isn’t too hard to comprehend why they don’t gravitate to us, prefer us, or feel safe with us. We have our work cut out to become someone they can trust and with whom they enjoy working. And if we protest and say that they aren’t worth that to us, that’s fine, but then we can’t begrudge others for choosing to develop a relationship with them that is filled with appropriate Positivity, Consistency, and Vulnerability. We either want as healthy of a relationship with our bosses as possible, or we don’t.

If the answer is yes to all of those questions, then the real questions to examine are: Why does it really bother me then that my boss appears to have some closer friends? What am I really feeling? Is this just my ego whispering worst-case scenarios in my head or is something I value at risk? What is that thing I value? Can we try on different options and try to name the thing we want that we think is missing? More of their attention? Their friendship? A promotion? Assurance that my job is safe? More enjoyment in the workplace like they seem to experience? Clarity in what’s expected of me? Understanding of how roles are distributed? The feeling of being special? More empathy for my situation? What specifically does that friendship represent to me that I think can either get me something I need or protect something I don’t want to lose?

Allan, who was the lead on a product launch, shared with me how much he wished one of his employees had come to him earlier. “I had no idea how annoyed Kim was with Mike, but she felt I favored Mike’s ideas, opinions, and suggestions over hers.” Unfortunately, without her asking, “How can I help make sure my ideas are heard?” she unconsciously chose the route of undermining Mike by basically asking, “How can I make his ideas look bad?”

This happens more than most of us even realize. When we feel threatened, it’s often easier to look for a target to blame than it is for us to look for a way to improve a relationship. Kim ended up losing trust with her boss, and the team, as she developed a reputation for being the one who always harshly judged the ideas of others. I asked Allan what he wished he knew sooner, to which he said, “I honestly wish she had come to me and just said, ‘I’m having a hard time feeling like my ideas are being heard in our team meetings. I know they’re not all good ideas, but I really do want to be a team player and contribute as much as possible.’ Had she done that, I not only would have been impressed with her commitment to our work, but it would have helped me examine whether there were better ways I could run the meetings to make sure everyone felt safe. Clearly there was a growth opportunity for me that we missed, and now the whole team feels unsafe brainstorming.”

So our supervisors might gravitate to a colleague who makes them laugh a lot, might enjoy the way another can talk about a favorite activity with them, might lean heavily on someone who they know they can rely on for follow-through, or might frequently want one person’s wise counsel because they appreciate the way that person approaches situations. None of that takes anything away from who we are, what we can contribute, and how we can develop the best relationship possible with them.

I’m not saying that close friendships with leaders are appropriate in every work setting. So much depends on the culture of each company, the type of work we’re doing together, the makeup of a team, the emotional health of the friends, and the skills of the leader. But because some of us will bond across the lines of our roles, whether we mean to or not (or not want to “break up” just because one of us gets promoted), let’s take responsibility to have more conversations for how we can support friendships in ways that minimize the downsides and maximize the potential.

May we each find our own way to make our biggest contribution at work and build our own meaningful connections, all while trying to trust others to do the same.