We no longer find ourselves before subjective or objective images; we are caught in the correlation between a perception-image and a camera-consciousness that transforms it.

—Gilles Deleuze, Cinéma 1: L’image-mouvement

WHEN WE ARE WATCHING A FILM, IT OFTEN SEEMS AS THOUGH we are looking through a window onto the world, or as if the camera itself were a set of eyes, looking at the world for us—perhaps both of these at once, even. The camera moves and the image shifts, or the sequence cuts to another shot, and it is as if an idea was created, a train of thought, and yet it wasn’t only in our heads. It was on the screen, in the film’s process of unfolding, part of the process of becoming that takes place before us. Is film a type of perception? Is it a type of consciousness? If it is, what is doing the perceiving, the thinking? Who is the “I” of this experience? Is the viewing subject absolute and set apart from the object of its gaze, or are we—as Deleuze implies—implicated in the flux between two states of perception and understanding?

In this quote, Deleuze exemplifies a tendency in film theory to describe cinema by referring to characteristics of human experience, using terms like camera-consciousness and perception-image to relate film representation to some aspect of what we consider internalized, subjective experiences: thought, consciousness, perception. From the early views of Jean Epstein and Sergei Eisenstein to the recent proliferation of post-Deleuzean notions of the film-mind, theories of cinema have been greatly slanted toward metaphors that compare cinema to human mental processes. Scholars and theorists (myself included) face here what I would say is essentially a problem of terminology, in which such metaphorical models tell us less about cinema than about our own means of describing it; to paraphrase Wittgenstein, the limits of our language define the limits of our world, and the limits of our film theory are defined by the traps we set for ourselves in our choice of analogy, metaphor, and phrasing. Yet, there clearly are similarities between film form and our own ways of experiencing the world. In hopes of grounding such similarities and analogies in a more philosophical bedrock, I will look here at some preliminary problems of human subjectivity as described through phenomenology and establish some basic intersections between the work of Merleau-Ponty and the construction of the primary degree of film subjectivity: the viewing subject.

Perhaps the most generic analogy in film writing is that which theorizes a type of camera-perception. As Dudley Andrew notes, many proponents of cinematic realism, such as André Bazin and Siegfried Kracauer, see “little essential difference between perception in the cinema and in the world at large.”1 However, while the subsequent assemblage of its recordings can be presented as an act of perception, a machine does not provide an act of perception but an act of recording and, then, of representing. And the metaphor goes deeper, past our instantaneous interaction with sensory phenomena and to our very psychological makeup. We may all be familiar with cross-references between cinema and human psychology, a connection made by early psychologists-turned-cineastes such as Hugo Münsterberg, whose Psychology of the Photoplay would be inadvertently elaborated upon in Jean Mitry’s 1965 The Aesthetics and Psychology of the Cinema. Such approaches usually refer to the Gestalt model of psychology, which focuses on the perceptual apparatus as a system of organization that translates external phenomena into a set of spatiotemporal relationships that together form something more than just the sum of their respective parts. The structuring of the film image can be compared to the human perceptual gestalt: in the writings of Arnheim, Münsterberg, and Mitry, as well as Merleau-Ponty, there is a similarity between the organizational process of human perception and the manner in which the film image, interdependent on the medium’s specific formal elements, organizes external phenomena into a larger worldview.

Moreover, as Vivian Sobchack writes, “the film experience is a system of communication based on bodily perception as a vehicle of conscious experience.”2 In other words, not only does film form simulate certain qualities of human psychology, but we also experience film through the senses, and as such it acts as a relay for phenomena to our own human apparatus, distributing the sensible once (when the film is being recorded), twice (during postproduction, when the sensory elements are being mixed and edited), and thrice (through the exhibition methods that present the final text to the spectator). However, this triple distribution is often smoothed over, rendered invisible, for our viewing pleasure—or, more skeptically, for the preservation of a dominant order of meaning. On a basic, illusionist plane I will look here at how the film image offers a mode of representation that implicitly claims its content as being directly witnessed, or experienced, because its form of presentation mimics the sensory process through which humans experience the material world. Christian Metz formulates this process as follows: the film image constitutes a source-point for the spectator to inhabit through identifying with a pure act of perception.3 The image offers us a position for viewing, from which vantage point the visible content seems less like a cultural text and more like a chunk of some ostensible reality.

At the same time, however, as gestaltists such as Arnheim point out, film form includes many effects, such as the projection of a two-dimensional image as three-dimensional, that draw attention to the “unreality of the film picture.”4 For Arnheim cinematic realism is not a natural inclination of cinema but an affectation. As such, as is a fundamental argument of this book, one should be wary of the notion of film as itself offering an empirical or natural mode of observation. This “natural” connection is itself the connotation of a type of image and has been discounted as much by ideology theorists of previous decades as by a heightened cultural literacy of contemporary audiences, yet even today’s reliance on video-grammar codes of truth evoke realist approaches that stipulate a natural ontological link between human observation, the camera-apparatus, and the inherent meaning of external phenomena. I will look in this chapter at the basis for such an understanding, and in the next chapter at the complications posed to such an approach by a semiotics that has a phenomenological basis. If such a theory has already been highly challenged, you may ask, why revitalize this debate? In assessing the parameters of this argument, I hope first to reveal the methodological intersection of variant theories as, ultimately, theories of film connotation; and, building from this, I aim to explore the analogy of film and perception according to the central pursuit of where film and philosophy meet, how this analogy—in its accuracies and flaws—might offer us entrance to the philosophical nature of the medium and films discussed here.

While Andrew is correct to acknowledge that the idea of cinema’s being a system of signs seems to remove from it the capacity for “revelation,” this same medium can still help to dissolve the division between the viewing spectator and the viewed world.5 This does not mean that cinema is a window on the world, providing some innocent and neutral viewpoint but, instead, that it is able to perform an important phenomenological dissolution of the subject-object binary. I will thus argue for a phenomenological notion of cinema based not on the camera as a perceptive vehicle but on the flow of cinematic meaning as a dialogic openness between different subjective positions, an immanent field where the content of the image and the human manipulation behind its production meet, thus returning us to Deleuze’s quote at the beginning of this chapter. To strip his claim of its metaphors: the image is neither objective nor subjective but a process of transformation that structures itself according to subjective or objective systems of reference. In other words my concern here is not the outside, or the objective world that exists anterior to any subject’s experience of it; nor the interiorization of this reality, a subjective experience that renders all meaning relative; but, the image’s collusion between these two. That is to say, the image consists not only of the objects it represents, nor of a particular character’s vision of this world, but also—and perhaps most fundamentally—of our use of these two conditions of differentiation as the basis for meaning. These two connotative orders—the objective mode differentiating between detached apparatus and world viewed, and the subjective mode differentiating between diegetic subject and diegetic world—construct two very different systems of reference, yet both are conventionally used to divide the subject from the content represented and are thus similar in producing a closed order of meaning. Before getting ahead of myself, though, let me return to the degree zero of film subjectivity: the viewing subject as it is correlated with an objective mode of representation, and the philosophical importance of this myth of camera-perception.

FILM’S PRIMARY SYSTEM OF ORGANIZATION: THE FRAME AND THE VIEWING SUBJECT

It is, of course, extremely difficult to claim one particular element of film expression as the primary level of filmic anything. I would agree, however, with most arguments that the single visual shot—the framing and composition of the shot—is the most basic unit of film expression (though we will soon find that, in the feature-length fiction film, this does not make it self-sufficient or impervious to a multitude of influences). The shot, as Raymond Bellour writes, is “le premier lieu” (the starting place) for film expression, through which the image institutes “its voyeuristic position as organizer of the real.”6 To calibrate this to my argument here: the shot is the primary unit of expression because the frame provides us with the first differentiated impression of a subjective position. It may be helpful to pause here and ask, What is a subject? Subjectivity, we could say, is an enforced system of differentiation that posits a unity of meaning or logic on one side and an object to be understood on the other. The visible elements of the image refer to the frame as a system of separation and limitation, and the frame refers to a viewing position as its origin. By enforcing the spatial system of difference in the visual image, the frame provides a system of reference, an implied subject of the gaze through which the visible is seen.

This system of reference signifies that the image is the correlation of a worldview with a subjective viewing position. The system of reference’s formal praxis is the structure of the shot, the components of which—including composition, depth, movement—refer ultimately to the limitation of the image: the frame. As the defining structure of what is included in or excluded from the filmic message, we could view the frame as the film image’s initial praxis for organization, a permanent system of reference that is part of any film representation. While it seems slightly monolithic, I agree with Mitry’s claim that all visual elements are fundamentally attached to the frame: “All plastic significations depend on it.”7 Yet, I see no reason to claim, as theorists such as David Bordwell and Stephen Heath have, that the frame’s organizational process is fundamentally narrative; although it may often be situated in a narrative context, it is first and foremost an organization of spatial relations. And, regardless of whether or not it is used in a story, the process of framing serves to differentiate between a subject and a content or object of the image.

This structuring process is a motivated simulation—engendered by the medium’s forms, I will argue—of the transcendental condition discussed in phenomenology, and it would be helpful, therefore, to introduce aspects of the condition described by the phenomenology of perception so as to integrate such concepts into a semiotics of film connotation. Merleau-Ponty’s most devout study of gestalt perception, Phenomenology of Perception, insists on the fundamental premise that an object’s form and size are accidents of our relationship to it.8 According to Merleau-Ponty, depth-of-field and vertical and horizontal relativity are arbitrary processes carried out to produce a vis-à-vis between a perceiving subject and the world of objects.9 Spatial perception, we can gather, is a structural phenomenon, not an essential natural aspect, and is understandable only to the extent that it is founded in a particular subjectivity, and the positing of this anchor via the organization of the objective world according to such spatial designations is what could be postulated as the universal condition of the subject.10 All subjects define themselves through this mode of organization.

Consequently, although symbolically, cinematic space—as constructed during a shot and according to the frame—implies the existence of a viewing subject that is the source of vision, placing the spectator in this position. As Colin MacCabe and Laura Mulvey write: “The world is centered for us by the camera and we are at the centre of a world always in focus.”11 This “centre” is defined by the frame, which functions according to an analogical relationship with real perception, a claim that is further supported by the manufactured correspondence between the horizontal-vertical ratio of the cinematic image and that of human vision. Ronald Bogue, writing on Deleuze and yet conjuring the preceding points by Merleau-Ponty, articulates this well: “Every frame implies an ‘angle of framing,’ a position in space from which the framed image is shot.”12 This is not an uncommon claim, but it is important to articulate here. As an organizational mechanism, the fact that the frame delimits the image creates a system of reference that, at the most basic level, refers to the frame itself as a relay for the parameters of the perceiving subject. Other aspects of film optics whose place is within the frame can also be seen as analogous to operations performed by Merleau-Ponty’s human viewing subject; thus, the elements that interact with the frame imply that basic visual representation is a simulation of human vision. For example, shot scale can be used to mimic the human experience of casting attention to one particular area of vision, as in Münsterberg’s understanding of the close-up.13 In addition, there is camera movement, which grants the frame the illusion of a certain lifelike mobility, as if it were itself moving through space. Furthermore, there is the illusion of depth-of-field, which utilizes the convention of perspective in order to situate the viewer in a familiar position of relating to the world.

This effect, which I will consider in more detail in my analysis of film objectivity in chapter 5, is only part of the film image’s inheritance of Renaissance artistic conventions, as Stephen Heath points out: including stability (easel), movement (camera obscura), and depth (perspective), these effects are meant to provide a “whole vision” that is delimited within the frame. But Heath uses these attributes, combined with the conventional purpose of framing in fiction cinema, to define the frame as “the conversion of seen into scene.”14 The continuity of the content or narrative information exchanged, however, is only the end—not the predetermination—of the frame’s codification of visual perception, and, as such, I would encourage that we consider this conversion to be a question of form before it is integrated into a question of narration. The frame is not, as Heath claims, “narrated”; it is not a result of the logic of the story but is part of the mold for that narration, a channel for that message, regardless of whether it is mimetic or another type of message.

In summary: as a spatial determinant for the organization of visible relations, the frame selects the fragment of possible reality being transmitted as information. For the visible space within the shot the frame is, as Mitry puts it, “the absolute referent of all cinematic representation.”15 Mitry, who comes from a phenomenological background, claims that the objects-turned-images are constructed with boundaries constituted by the frame and, as such, are linked to it phenomenally through an immanent field of formal organization. This implies a certain motivation or rhetorical nature of the form itself that is prenarrative. Because it serves as the center of gravity for what is in the image, the frame is responsible first and foremost for constructing the relationship between visible subjects and objects, thus determining the relational structure of difference within the visual diegesis. How are characters arranged relative to each other in the frame? But, also: what is allowed in the frame and what is excluded? After all, the frame not only pulls things into a common space; it also divides them. The elements in a frame, as Deleuze points out, are both distinct parts and components of a single composition, which the frame both separates and unites.16 The frame divides its content: it is essentially selective, though there is one thing at all times both included and excluded: the viewing subject.

Second, though more subtly, the frame determines the relationship between the spectator and the visual objects, thus determining the spatial structure through which the spectator is given the visual content. This does not make such an organization essential to the object itself, but it is inevitable, as delimitation is a necessary aspect of any process of organization. Merleau-Ponty describes this act perfectly with regard to natural vision: “The limits of the visual field are a necessary moment in the organization of the world and not an objective contour.”17 This necessary moment, which must be seen as both motivated (in that it is selective) and arbitrary (in that this selection produces an artificial division that does not stem from the object itself) is, I believe, what is simulated in the shot. On both of these levels the process of delimitation exercised by the frame must be accepted as a necessary moment, but we should resist the naturalization of it as an objective characteristic. This resistance is of interest here because, through film connotation, such an arbitrary allotment is often given the impression of being naturally essential, objective. As Arnheim puts it: “a virtue is made of necessity.”18

All elements of the shot—movement, depth-of-field, mise-en-scène, etc.—refer back to the frame as the center or source of this necessary act of organization, designations that assume a vis-à-vis of subject and world. This vis-à-vis is a relational system, an inherent rupture between viewing subject and visible objects that implies a condition for the spectator as being part of a division between perceiving subject and perceived world. This implication, a rhetorical effect through which the arbitrary difference implied by perception is granted an essential value, is a problem of film connotation and thus of philosophical importance. “A virtue is made of necessity.” Arnheim’s statement summarizes the philosophical problem proposed by the previous pages’ exploration of phenomenology and the film frame. The frame is the ultimate referent of everything in the image, yet it is limited by its formal determination—though different films may use different aspect ratios, the frame is always limited, and must be arbitrarily fixed. Yet this arbitrary placement defines the rational integrity of the image, like the parameters of a scientific experiment. Not only does the frame determine the limitation of information, but it also imposes a relationship of differentiation and implies that the content viewed is an absolute totality for the viewing subject. Deriving totality from limitation is a fundamental tenet of the classical philosophical order of meaning, the essence of cliché, and perhaps the single most challenged principle by the skeptical or subversive philosophies of Merleau-Ponty and Deleuze.

The connotative ramifications of this vis-à-vis, here analyzed with regard to the primary level of the shot, constitute what I will call the myth of natural perception. Through this phrase I hope to convey the notion that any shot signifies a point-of-view according to which it is produced, and the myth by which this image can be accepted as an act of perception is integrally linked to the implication or connotation of totality accorded to this view. As Colin MacCabe writes: “that which institutes the object as separate also institutes the subject as self-contained unity instead of divided process.”19 And, I would say, vice versa. The myth of cinematic perception functions according to the following convention: the screen acts as a window, and the visual content is what we see as we look through that window. The shot can deliver to us a nonsensical or unfamiliar message, but it is always one that can be seen and therefore interpreted as an image of something. As Metz argues, this principal effect allows the spectator to identify with him- or herself as the condition of possibility of the perceived,20 an argument common to the psychoanalytic approaches of Metz, Bellour, and Baudry.

Although I remain suspicious of the psychoanalytic basis for such an argument, the notion of subject-formation can be traced back to the phenomenological subject-function. The shot gathers all illusions necessary to convince the spectator that, while what you are seeing through your normal perceptive process may be something that you could not see outside the cinema, you are seeing it nonetheless through your normal perceptual process, therefore legitimizing the spectacle as possible reality or what Barthes might call the vraisemblable, “that which the public believes to be possible and may be completely different from the historic real or scientifically possible.”21 In other words, to elaborate on an argument that is implicit even in realist theories of cinema, any resemblance between the image and the possible—not the real, but the possibly real—lies in the form of perceiving whatever is denoted and not in the content perceived. As Baudry puts it: “the spectator identifies less with what is represented, the spectacle itself, than with what stages the spectacle, makes it seen, obliging him to see what it sees: this is exactly the function taken over by the camera as a sort of relay.”22 The notion of the camera as relay, which is the condition for what Baudry critiques as the classical cinematic identification with the subject of visual perception, is based on the construction of a subject that, according to the principles of phenomenology, is itself a myth. The filmmakers explored in this book challenge both this myth and the assumption it produces—but first, I will further this analysis of the philosophical implications of popular analogies of the image-as-perception or image-as-thought and how such divergent theories might be reconciled by understanding their underlying methodologies as, fundamentally, problems of subject-object relations.

SHOT(S): THE EISENSTEIN-BAZIN DEBATE

The myth of natural perception and the isolated subject is impossible to avoid in the individual shot, for the unidirectional nature of the camera guarantees just such a relational structure. But this book is concerned with the cinema: it takes twenty-four frames to complete a second of screen time, and each shot is surrounded by other shots and combined to form scenes, which are combined to form sequences. Each shot inevitably refers to its own unique viewing position; and, as Bellour writes, “film is a chain of successive viewpoints.”23 What changes with a juxtaposition of different shots? In other words, where does the viewing subject fit into the relationship between shot and editing? Positions taken in response to this question can be viewed as threefold, systematized according to the epistemological and ontological beliefs on which they are founded.

First, there is the notion that cinema has an ontological ability and responsibility to capture meanings on the surface of external phenomena, a notion developed by realists such as André Bazin. Bazin suggests that film signification ought to be grounded in the meaning produced by the objects it is recording. The formal organization should be governed, then, by its preservation of spatiotemporal unity, “the simple photographic respect for the unity of space.”24 The uninterrupted shot is therefore considered to reveal a meaning that is immanent in some presignified state, implying the film image to be an act of pure perception that offers an objective window on the world.

Conversely, there is the notion that meaning is produced by a juxtaposition of shots that gradually constructs a mental whole, or “image” in Sergei Eisenstein’s terms.25 Cinema’s specificity would lie, therefore, in its ability to mimic the process of association through which the mind reaches a dialectical understanding of the world. As such, film is aesthetically determined by its ability to organize singular ideas within syntactic relationships, its “imagist transformation of the dialectical principle”: montage.26 The sequence should mimic the act of consciousness and guide the spectator’s reaction, suggesting that film is a subjective process that must produce meaning beyond the content of its individual shots.

Last, there is what I will call the phenomenological notion: that meaning lies in the interaction between the object and the subject of the image. This is my theory of the immanent field. I say “phenomenological” because, in this case, meaning lies neither solely in physical objects nor solely in the subjective apprehensions of these objects but in the interactive flux that binds the former to the latter, what Merleau-Ponty sought as “the synthesis of the subjective and objective experience of phenomena.”27 As Martin Jay argues, phenomenology aims to shed the Cartesian assumptions of a “spectatorial and intellectualist epistemology based on a subjective self reflecting on an objective world exterior to it.”28 In other words, and particularly in the works of Merleau-Ponty, phenomenology implies an attempt to understand both personal and artistic experience as a destruction of the hierarchy, dualism, and even the separation between subject and object. In his rejection of the transcendental subject, Merleau-Ponty dreamt of “regaining the experience of the intertwining of subject and object, which was lost in all dualistic philosophies.”29 According to such an approach, cinema’s specificity would lie in its ability to dispel such a duality on numerous levels: within the shot itself, in the interaction between shot and sequence, and in its ability to change between and even integrate objective and subjective poles of representation. This is where film meets philosophy—not what films always do, but what film form is equipped to do.

Cinema helps to remind us that looking is itself an interaction with the world, and the medium can shift perspectives to alter our very notion of subjectivity. In doing so, it can open the immanent field as a praxis for the discursive interaction between characters, spectators, and the apparatus itself. Such a cinema challenges the division, or “clivage” as Merleau-Ponty puts it, between subject and object that is the basis for classical representation. By being able to show how we show, to bring to light how we signify and what our conventional forms connote, cinema is capable of breaking down the division instituted in our conventions of looking and offers the potential to achieve the fundamental goal of phenomenology: “to contest the very principle of this division, and to introduce the contact between the observer and observed into the definition of the real.”30

This contact between viewer and viewed is a central topic of debate in film theory in general, and it has helped to shape many theorists’ basic use of philosophy in analyzing the Seventh Art. The frame separates the viewing subject from the viewed world: what does this mean in terms of entire projects of cinematic expression and film criticism? As I propose in my introduction, this study aims at reconciling opposed approaches to film theory, and I will therefore look now at the aforementioned contrasting theories of Sergei Eisenstein and André Bazin, two examples from the canon of film theory that etch out two definitive stances on the philosophical possibilities of cinema. These positions are founded on opposing views of how cinema’s transformation should mediate between world and spectator, and they offer especially good examples of how such concerns are articulated in terms of the relationship between shot and sequence—a formal binary particularly useful to rhetorical arguments that, I will argue, imply specific arrangements of subject-object relations. A detailed look at these theorists will help me to build a comparatist framework that will run throughout this book, as their differences reveal a fundamental rift between subjective and objective models, models that these theorists articulate according to a clear designation of how film’s formal base can and should operate.

In “Two Types of Film Theory” Brian Henderson offers a useful platform for entering into this debate: “The real is the starting point for both Eisenstein and Bazin.”31 As Henderson continues, however, neither theorist provides a doctrine or definition of the real. Instead, their approaches are based on “cinema’s relation to the real,” a relation that is embedded for each in the formal interaction between shot and sequence. Polarized representatives of the duality between shot and montage, Eisenstein’s and Bazin’s respective theories are constructed around particular beliefs in film’s capacity for simulating aspects of human subjectivity, be it as consciousness (Eisenstein) or perception (Bazin). Breaking down these analogies between formal cinematic practices and human processes of relating to the sensory world, I hope to provide a bridge between Eisenstein’s and Bazin’s viewpoints, weaning from the ideological trappings of each what are very useful insights concerning film meaning.

Both theorists extol cinema as an art but toward different purposes. On one hand, Eisenstein considers cinema an art only insomuch as it manifests conflict as its generative origin of meaning.32 Conflict, realized through various levels of montage, creates juxtapositions that transcend the mere fragments of reality that one calls a shot, providing a more profound meaning than is offered by the content of a single image—as if presenting a thought or feeling. Bazin, on the other hand, views such an approach as a stylized manipulation of reality that should be avoided, as it distorts the world’s original meaningfulness. According to Bazin’s “Ontology of the Photographic Image,” cinema is the apotheosis of art’s attempt to preserve nature, to provide a replication as defense against our own mortality; and nature, for Bazin, is unified but ambiguous.33 He thus focuses his aesthetics on a critique of montage as a manipulation of the ambiguity inherent in the photographic image’s reproductive capabilities. The shot, however, is capable of preserving the complex meaning and spatiotemporal unity on the surface of external phenomena.

Henderson is perhaps incorrect, or at least exaggerating, when he criticizes Eisenstein as negligent of the aesthetics of the individual shot and Bazin for having “no sense … of the overall formal organization of films.”34 After all, Eisenstein wrote quite extensive analyses of the composition of individual shots, and Bazin possessed a unique ability to understand film texts according to their general aesthetic themes. Henderson is correct, though, to indicate the dichotomy between shot and montage as being central to what divides the two theorists, a division that is directly connected to their respective views on the ontology of film and its correlation to human experience. Like many of his Soviet contemporaries, Eisenstein insists that cinema is not meant to portray the world but to exceed it, to transform it: montage is, in his terms, the “means for the really important creative remolding of nature.”35 It is only through juxtaposing individual representations of nature that one can create an “image,” a product (totality of juxtaposition) that qualitatively changes its factors (the individual representations that were juxtaposed).36 Eisenstein adapts this central notion of juxtaposition to numerous elemental relations in film form, though it is particularly charged in his theory of montage between shots. The content of the frame is only a building block, the shot itself but a part of a greater whole. What is in the frame is only a stimulus to be combined with other stimuli, and the subject posited by the frame itself is subjugated to a transcendental associative subject that builds larger meanings from the juxtaposition of shots. For Eisenstein the immanent field takes shape on the level of sequential construction.

The overall effect of this interaction between elements is what Eisenstein considers a “transition from quantity to quality,”37 as if the placement of two shots together suddenly renders each one something other than a shot, something more—something, perhaps, of philosophical impact or importance. Each shot affects the meaning of the other, and the consequent alteration of meaning further changes this relationship, thus retransforming each individual meaning once again. The final whole, or “image,” whose overall meaning is not a picture but a dialectical process, Eisenstein considers analogous to human consciousness: “In the actual method of creating images, a work of art must reproduce the process whereby, in life itself, new images are built up in the human consciousness.… To create an image, a work of art must rely on a precisely analogous method, the construction of a chain of representations.”38

The construction of this chain is what is known popularly as montage, and it provides the spectator with a constructed illusion of the dialectical process through which one gathers perceptions over time and builds composite understandings within a subjective arena separated from the objective origin of these individual perceptions. When Eisenstein refers to an “analogous method,” he does not mean the analogue reproduction of material objects, but a structural similarity between the organizing process of film and that of human consciousness. Though looking at the interaction between shots as forming a larger immanent field of the image, I consider this not only as the construction of an overall system of reference but also as the interaction between multiple subjective positions. For the sake of propaganda Eisenstein avoided this interaction. Working in an overtly ideological context, he wanted to control which resultant judgment the spectator would arrive at. This manipulation consists of rhetorical practices generated through the relationship between mise-en-scène and montage. A classic example with which the reader may be familiar is from the closing sequence of Eisenstein’s Strike (1925), which cuts from the image of Tsarist soldiers attacking a group of striking workers to a shot of a butcher violently slaughtering a bull, thus guiding the spectator to an understanding of the state police as hired murderers who treat the proletariat like animals. While Eisenstein clarifies for us the expressive potential of montage, I believe this to be a theory of how to use the image to achieve certain results, a notion of film embedded in a specific polemical strategy and not in determinants of the form itself. On a broader contextual level, Eisenstein’s theories are ideologically attributable to a particular moment in history—the birth of Soviet communism and the promise of industrial utopia embraced by formalist artistic movements of the interwar period—that, in the wake of World War II, generated much skepticism as a result of how such rhetoric played out in the arena of global destruction and genocide.

Illustrating a historical intellectual shift toward rejecting the technocracy of fascism, film theorists after the war abandoned a certain idealism of what film expression could do to surpass the meaning inherent in nature and moved toward an argument that cinema was essentially meant to offer a nonbiased depiction of reality. Writing in the 1940s and 1950s, Bazin condemns the very style of manipulating reality that is central to Eisenstein’s model, shifting his focus onto the camera’s ability to reveal the meaning held in the source reality. In his seminal essay, “Ontology of the Photographic Image,” Bazin traces the genealogy of art as the evolution of a primordial attempt to preserve humanity by reproducing it in the form of the image: “to save being through appearance.”39 For Bazin, however, this evolution was diverted by painting, which added an aesthetic aspect to this psychological desire for reproduction. This drift toward expressive manipulation was for Bazin the great sin of the Western artistic tradition, one that photography and, subsequently, cinema would rectify through the essential objectivism innate to the camera’s mechanical process.40 In conclusion Bazin claims that this “solution” lies not in the result but in the genesis of this reproduction, from which—in the case of the mechanical camera—man is excluded. For Bazin this gives cinema a particular ontological tendency toward aesthetic realism. Bazin is arguing for film as a transfer of the immanent field of reality itself. His writings extol cinema’s potential to relinquish signification to its viewed source. But this leads to the inevitable question: of what does representing reality consist? I will argue that, for Bazin, this concept is grounded not in the content but in the form of the image—that is, it is a theory of film connotation.

Summarizing Bazin’s argument, Peter Wollen writes, “Bazin’s aesthetics asserted the primacy of the object over the image, the primacy of the natural world over the world of signs.”41 Bazin argues for a mode of cinema that embraces its potential as a reproductive tool, implying that the direct representation of material phenomena is a problem of form. Therefore, despite a general neglect of this facet of Bazin’s argument, one could say that he is, in fact, very much concerned with film signification. Indeed, Bazin is not as naive as he is often accused of being: after discussing cinema’s inheritance of photographic objectivity, he ominously ends his “Ontology” with the observation: “On the other hand, cinema is a language.”42 The impression of objectivity—like any connotative system—is never detached from the forms through which it is constructed. Bazin takes a particular side in his view of what cinema should be, an argument that takes shape according to a division between the semiotic ambiguity permitted by the shot and the semiotic certainty provided through montage, though Bazin does not himself explicitly refer to it in terms of semiotics. Bazin’s most fervent formal argument is against the use of montage, claiming that it is an artificial dissection of the continuity of natural space-time and thus violates the precious ambiguity of reality.43

Whereas my book is concerned with ambiguity as being internal and essential to the image itself, and in fact very much where film and philosophy meet, ambiguity for Bazin is a criterion of realism, a property of the objective world. For Bazin the shot preserves the ambiguity of the world as it appears in natural perception, while editing tries to force one particular meaning onto a situation. Though “the abstract nature of montage is not absolute, at least psychologically,” Bazin sees an absolute psychological function in the unity of the shot.44 Bazin holds the subjective position posited by the frame as something sacred, because it allows for the ambiguity of what may pass in front of it, placing us in front of the real, whereas montage only alludes to the real.45 We can make an important deduction from this evaluation of art and its mechanism: what is essential to Bazin’s argument is not the real object itself but the phenomenological connotations of the mode of representation. Orson Welles’s greatness, for example, lay not in his preservation of particular objects’ essences but in his restoration of spatiotemporal continuity to the cinematic image, thus providing the spectator a certain ambiguity of perception through an unmediated visual depth.46

For Bazin cinematic objectivism is ultimately a matter of style (the negation of style is indeed a question of style!). Dudley Andrew frames this paradox as such: “arguing for a style that reduces signification to a minimum, Bazin sees the reduction of style as a potential stylistic option.”47 This conflict is apparent in Bazin’s constant attempt to uphold the phenomenological traits of neorealism: he claims that the movement’s common modes of representation know only immanence, a direct contact with sensory phenomena and the concrete world; yet he also finds it necessary to explain neorealism’s individual aesthetic traits in terms of particular psychological characteristics of the diegetic subject (such as with the drab vision of bourgeois mediocrity in Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy [1954]).48 In other words, this stylistic reduction is still laden with signification, and one can extend this analysis to view the image as an immanent field wherein the subjectivities of the characters and of the apparatus interact. Despite many criticisms to the contrary, Bazin’s view of neorealism is admittedly a connotative argument. Neorealism, he argues, is a humanism (“un humanisme”) before it is a style of mise-en-scène, a worldview before it is an artistic school—a philosophy before it is a cinematic movement.49 As such, Bazin’s body of theory demonstrates how form itself, and specific formal practices, can provide the framework for a metaphysical understanding of the image.

I posit the split between Bazin’s and Eisenstein’s views of cinema as a connotative disagreement over whether film should be objective or subjective, as if they were approaching the image from opposite sides of the phenomenological spectrum. Whereas Eisenstein champions the subjective result of perception (the mental digestion of the seen, “consciousness” or “thought”), Bazin hopes to salvage the objectivism at the material origin of perception (what is being looked at, “vision”). On a philosophical level this divide is bridged by Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology; in his 1942 dissertation, “The Structure of Behavior,” Merleau-Ponty reconciles what Vincent Descombes considers “the very French problem of the unity between body and soul” by showing that “I think” is based on “I perceive,” and I will follow this lead on a cinematic level by refusing to separate the two formal elements of shot and montage.50 Despite their differences, both signify—connote—to the extent that they imply the image to be a certain way of viewing the world, a certain type of image that provides a certain dynamic of subject-object relations. Each uses the frame to signify a subjective position; they just treat the subject of the frame differently.

This differentiation between observing reality and interpreting reality is an argument about film connotation based on the filmic distribution of subject-object relations, for observation and interpretation embody the two most common structures by which film differentiates between the image and the source of this image: the image-as-perception (referring to a mechanical viewing subject) and the image-as-consciousness (referring to a human subject). Because both of these are constructs of formal organization, it is important to remember that neither is more or less signifying than the other, more or less involved in a process of transformation, more or less genuine. But their interaction determines the order of meaning according to which the film itself becomes philosophical and, as such, can be understood in terms of how these theories breach the relationship between image and real. As Henderson notes, Bazin stops with the real, while Eisenstein goes beyond it.51 Bazin’s notion of cinema is a myth of the autonomy of the objective world, whereas Eisenstein’s is a myth of the transcendence of subjective interpretation. Both of these, however, are myths inasmuch as they are conventionalized, through formal arrangements, to appear as essential aspects of the film medium. They are also myths in their implied exclusion of one another, their attempt to naturalize themselves as being total and eternal, and by being constructed according to a unilateral system of reference. In other words, they each imply a process of denotation without a formal base; they are both ultimately connotative arguments, but each one hides its connotative intentions.

These myths can be reconciled, indeed must be, as most films are a combination of the two, fluctuations between subjective and objective images, balancing acts between shot and montage. As Henderson reveals, Bazin’s and Eisenstein’s respective theories could be greatly enriched by an analysis of the relationship between shot, sequence, and entire film, or an analysis between filmic moments and the larger philosophy governing the distribution of subject-object relations across the text. I hope now to contribute exactly this through a comparative analysis of two films by Jean-Luc Godard.

JEAN-LUC GODARD AND THE VIEWING SUBJECT

Through exploring the philosophical ramifications of a theoretical construct (the shot as basis for dividing the viewing subject from viewed world) and the opposition of two critical standpoints regarding this element of film form, a certain polarity of the immanent field has become clearer. To make the best critical use of this theoretical construct, I now turn my attention toward actual film texts. By comparing two of Godard’s films, I will look at how a shot’s system of reference can either be reinforced or contradicted through its place in a sequence and at what the connotative ramifications of this are. Godard proves especially useful here because, as Mitry notes, his modality of expression falls on the level of the sequence, through which he manages (though not always, I will argue) to destroy closed structures of meaning.52

Godard focuses on the sequential role of the sound-image, first as a replication of natural perception and, later, as a revelation of the illusionary basis of this replication. It should come as no surprise, therefore, that much criticism (usually positive, so one might call it praise) of Godard’s work revolves around impressions of ethnography, often resorting to the critical analogy of perception. For example, the renowned scholar Marie-Claire Ropars-Wuilleumier writes that Godard’s films show “what existence offers to perception in an instant.”53 However poetic this description may be, and however much Godard himself may often attest (in interviews and through his films) to such a goal, this is the very type of criticism I am hoping to avoid here, as it convolutes the philosophical importance of cinema as a fulcrum between the physical world, sensory distribution, and human thinking. Nonetheless, Godard certainly reveals time and time again a concern for the relationship between cinema and immediate experience. He refers in numerous interviews and articles to Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology, and his oeuvre poses many questions concerning the relationship between human perception and film representation. Yet an analysis of Godard’s films dispels the very myth of cinematic perception, in many ways through the constant self-reflexive revelation of the apparatus in his films. The self-reflexive mode developed in Godard’s films finds an ebb and flow in Vivre sa vie and Two or Three Things I Know About Her, each of which struggles—with varying degrees of success—with the notion of dialogism: dialogism, that is, (1) as a mode of existence shown to define the relationship between characters and the diegetic world and (2) as a structure of representation between the cinematic apparatus and the content that it transforms. I will posit this dialogism as a function of the immanent field that binds different voices and discourses.

These two films have much in common, from their technical production to their content. They were both shot by Godard’s regular cinematographer during this period, Raoul Coutard, thus providing a continuity of visual sensibility; moreover, each film is about daily life in Paris or its suburbs, a city increasingly marked by signs of consumer capitalism and indifference to its human inhabitants. More specifically, each film regards a woman’s balance of daily life as a prostitute, the quotidian struggle of an individual that is marginalized in patriarchal society. Not only are these films about prostitution “as a metaphor for the study of a woman,”54 as Siew Hwa Beh comments, or as a symbol of woman as others have remarked; they are, in Godard’s words, films about prostitution as a metaphor for life in Western capitalist society, where “one is forced to live … according to laws similar to those of prostitution.”55 Prostitution becomes an overarching metaphor in Godard’s work, both on the surface and in the depths of films such as Vivre sa vie, Contempt (1963), A Married Woman (1964), and Two or Three Things I Know About Her. As Wheeler Winston Dixon notes, “Prostitution, no matter what form it takes, is an obsession for Godard,”56 an epic metaphor that extends to characters’ behavior, society at large, and the philosophical problem of subject and object as manifested by film form and the conventions of film language. During this period prostitution serves as a load-bearing issue for Godard that implicates mainstream cinematic conventions in a critique of capitalist values, while also reflecting on a more existential problem of the individual being both subject and object, having agency and being used, according to the order of meaning enforced by the cultural practices and social interactions of Western capitalism. The problem of simultaneously being subject and object is not posed only on a narrative level, however; Godard, in fact, erects it as a fundamental formal problem of the image itself and of cinema as an institution. It is this form of representation that I am concerned with here, and a comparative analysis of films with similar stories should be a fruitful way to foreground the analysis of formal differences.

It is fascinating how two films can construct very different systems of meaning out of generally similar story points: woman, prostitution, the city, the cinema. Like all films, each of these has its own unique aesthetic structure, its own balance between part and whole, and, to extend the central problems of this chapter, its own treatment of the subject of the frame. Godard claims that Vivre sa vie was made with nearly no editing, more or less put together in the order that the rushes were returned.57 This claim to the low priority given to planned editing during the production shoot is supported by the film’s reliance on framing and movement to guard subjectivity at all times in the eye of the camera. Through-out the film, framing and camera movements provide the spatial alienation of diegetic subjects from each other, also denying the implication that any character is motivating the movements and shifts of the apparatus. Two or Three Things I Know About Her reverses this system, using montage and sound design to contradict the camera-subject and to represent the characters as objects that are also free as independent subjects. This destruction of the hierarchy between subject and object is accentuated by the use of offscreen voices and direct address, each of which challenge the autonomy of the viewing subject posited by the frame. Moreover, material objects—from small to large, faucet to building—are composed in the frame as if to manifest subjective agency, objects turned subjects through the connotative potential of cinematic form. The connections between subjects and objects (and other subjects) rest in the contextual bonds implied by the relationship connecting frame, shot, and sequence, an immanent field in which the difference between subject and object is constantly in flux.

Vivre sa vie and the Classical Viewing Subject

Godard’s third feature film, Vivre sa vie played an integral part in European art cinema of the early 1960s. Challenging traditional modes of film expression while also maintaining a certain classical aesthetic, it joins A Woman Is a Woman (1961) and Contempt as Godard’s eulogy for classical cinema.

As is the case for most of Godard’s films, the actual narrative substance is, in a conventional sense, quite sparse: this is the story of Nana (played by Anna Karina, Godard’s wife from 1961 to 1966, and the heroine of seven of his films during this time), a young woman in Paris who works in a record store and then becomes a prostitute to make ends meet. Much in the vein of Godard’s work in general, Vivre sa vie has been viewed predominantly as a film that “subverts conservative conventions and experiments with possibilities.”58 Reviews, almost unanimously laudatory, typically focus on the film’s inherent claim to being a sort of formal liberation and point to how this complements the ethnographic approach to the story. For example, Beh writes: “In order to deal with the complexity of the subject matter, the film’s structure and Godard’s style are an integral part of our understanding of Nana and prostitution.”59 Beh is primarily talking about the film’s narrative structure here, which is based on a transposition of literary forms (predominantly journalistic and novelistic) onto fiction film, such as in the use of chapter headings and sociological statistics. The style, however, does not help us to understand the character nor the topic of prostitution so much as it connotes its own neutrality as an image-type. I will argue, against the popular reading of the film, that Vivre sa vie maintains a philosophical classicism despite its progressive politics and innovative style. Few people familiar with this work refuse the opinion that it is a film of great aesthetic beauty, human tenderness, and stylistic innovation. I agree wholeheartedly. That said, and despite the film’s many gestures toward its own philosophical prowess (including a chapter titled “Nana Does Philosophy,” which consists entirely of a conversation between Nana and real-life philosopher, Brice Parain), it is necessary to debate romanticized readings of the text and to question certain contradictions inherent in its modes of representation, so as to consider the philosophical ramifications of its connotative order.

A principled defiance of illusionist cinema that is ironically rife with homage, Vivre sa vie employs Brechtian devices while retaining a visual structure that is faithful to an absolute camera-subject, an epistemological approach that places the origin of all meaning in the camera’s gaze. The film is not, as Jean-Pierre Esquenazi claims (vocalizing a wealth of similar criticism), the vision of a camera “endowed with an autonomous conscience”60 but is, instead, a network of representations meant to isolate the camera as the sole source of meaning, a camera that is, as Kaja Silverman points out, more motivated than Godard lets on.61 In other words it is a romanticized metaphor to claim that the camera itself has a conscience, and a fantastic exaggeration to describe a machine that requires human handling to be autonomous, though the image is constructed to give the impression of its being a type of image that possesses these faculties.

The introductory sequence of the film provides a key to this connotative platform. The opening credits are interspersed with three silhouetted shots of Nana: left profile, frontal, and right profile. Belying his roots in phenomenology, Edgar Morin points out that the succession of multiple shots with the same object allows cinema to set in place a process of complementary perception “that moves from the fragmentary to the total, from the multiplicity to the unicity of the image.”62 But is this practice natural, or naturalized? I would argue the latter. This sequence could be seen to simulate an epistemological process based on the following progression: the content in the frame is the object of inquiry; the understanding of this object occurs through perception; perception occurs through the frame. According to Merleau-Ponty, understanding is built on perception; does understanding therefore imply a perceptive act? Is this the philosophical trick Godard is playing, using the tools of film form for his connotative sleight of hand? We perceive; therefore, we understand; or perhaps more accurately: we understand; therefore, we must have perceived. Should the angle of viewing this content change, but the frame’s relationship to the object remain the same, it is as if there was one stable viewing subject, as if the same subject completed a circle around the object. In this series of shots we can see an attempt to construct a totality from multiple perspectives; though cutting among different positions, each shot is framed the same, refers to the same transcendental viewing subject.

The abundance of close-ups of Nana in the film has led many to view the film as a “documentary of a face,”63 suggesting Godard’s clear obsession with his real-life lover and also implying a truth-claim or documentary authenticity attached to the formal structure. While the camera may, for the most part, resist being motivated by narrative factors, it is systematically motivated by philosophical factors, to connote its resultant image as being a certain type of image. But what of the content of this documentary, the object of this humanism? In this opening sequence the character is captured in a manner that differentiates her as an object, an other being enclosed or encircled by a perceiving subject-function. The humanistic or ethnographic element of documentation is here a contradiction of method: the form acts as a sympathizing external representation of her psychological state while disposing of her independent subjectivity. Foreshadowing for us how this contradiction will be realized at the end of the film, the circle performed by the camera ends by slipping out of its own enclosed signification: the last shot is of Nana’s back, in a café, thus beginning the first scene of the narrative diegesis.

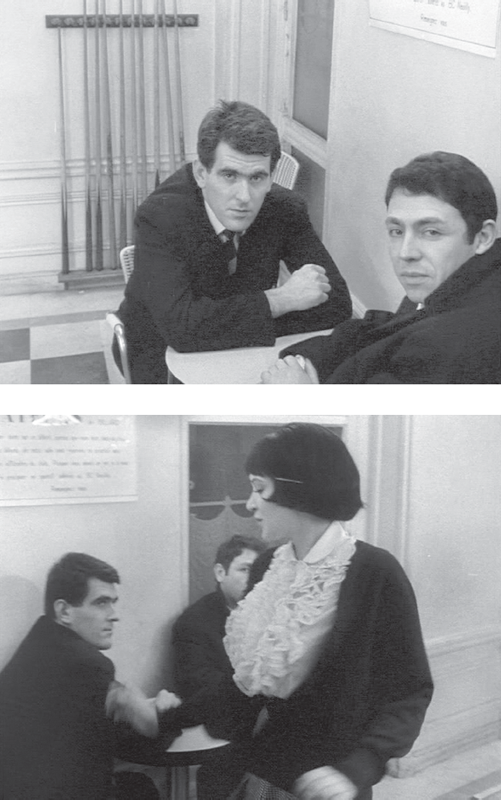

The entire first scene cuts between one-shots of two people seen from behind, never allowing them in the same frame at the same time, binding them only by their separation and by the space reflected in the mirror in front of them. This denial of faces is also in a way the denial of the identity of its perceived objects. Beh claims that this framing “immediately alienates us” as spectators.64 The frame’s relation to the image actually gives us a privileged position, however, slightly hidden and voyeuristic, alienating only the characters from each other and even from themselves (that is, alienating the sound of their voices from the image of their mouths). The system of reference, one could say, is protected, affirmed, rooted. Vivre sa vie thrives on a connotative limitation of the immanent field, an alienation of its characters both from the camera-subject and from each other, a dual effect of the frame constantly reaffirmed by what I will call the enclosed shift, a hallmark of Godard’s and Coutard’s visual style during this period. In the enclosed shift the camera tracks slightly from side to side, often having the effect of isolating a character in the frame while that character is meant to be interacting with another character otherwise in spatial proximity; this slight movement highlights the frame’s absolute nature, its impermeability and decisiveness.

Every occurrence of this effect takes place during a conversation, notable in a film that V. F. Perkins summarizes as “a string of suggestions as to how one might film a conversation.”65 David Bordwell cites this quote in leading to his own view that “Vivre sa vie’s stylistic devices achieve a structural prominence that is more than simply ornamental.” Yet, in keeping with the goal of his own methodology, Bordwell refuses to assign to them “thematic meanings.”66 I would argue, however, that we should assign to these devices the thematic meanings that Bordwell rejects, as the constant use of this visual pattern has identifiable connotative significance, expressed through the film’s structure of relations between the camera and the people it films. This effect heightens the tension concerning the interaction between what exists inside and outside the frame, revealing both how close two humans can be without sharing anything from their respective interiors and how the immanent field of the image can be closed. This closure, I will argue in the next chapter, is a function of the relationship between denotation and connotation. The frame seems to imply a sphere around the viewed object, like a Leibnizian monad; but, while it may provide continuity between spheres, it refuses their permeation. These two humans are not allowed to be part of the same stream of information, the same visual message. This thematic visual design guarantees the source of the frame as the origin of meaning, the subject according to which the world is organized, and everything in front of it is a series of disconnected objects. However, this monolithic system of reference is challenged a couple of times in the text, when the film grants Nana her due subjectivity, giving us an example of the dialogism we will find to be the defining characteristic of Two or Three Things I Know About Her.

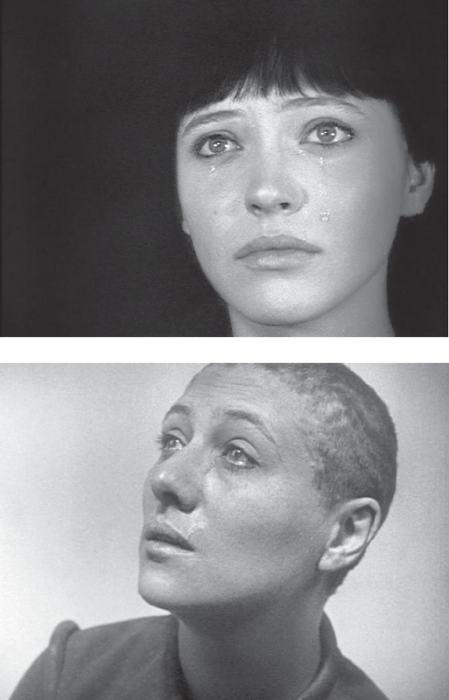

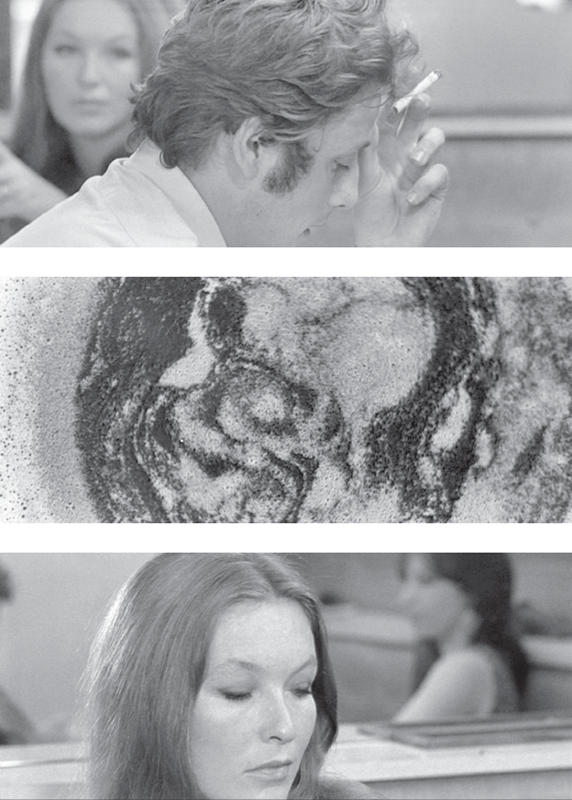

The best example occurs in the film’s most iconic scene, in which Nana sits in a cinema and watches the Carl Theodor Dreyer classic The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928).67 An intertextual montage, this sequence does not juxtapose two times or places but, instead, crosscuts between two entire connotative orders: as Nana’s tears echo those of the heroine in the film she is watching, we are absorbed into a self-reflexive crystal, and the immanent field becomes saturated with a second immanent field. This is Eisensteinian montage par excellence, as it conflates the two different visual subjects (the camera watching Nana and the camera watching Joan of Arc [Maria Falconetti]) and transcends them through the subjectivity of a larger relational structure. The spectator is caught in a mode of transferred identification that is all the more powerful because it is circular, because we see ourselves in Nana, in Nana’s viewing of a character in whom she sees herself (figs. 1.1, 1.2). The spectator is propelled by montage to identify not so much with Nana as with her process of viewing, her own act of identification with the tragic character, and as such Nana becomes implicated in the system of reference.

This mixture of self-reflexivity and intertextuality creates an effect similar to the Brechtian notion of distanciation, which can be found elsewhere in this film in devices—such as chapter titles and direct address—used to redirect attention toward the formal or connotative base itself. This particular scene allows a crack in the edifice of the camera-subject on two levels; the spectator is asked here to identify with Nana’s process of identification while at the same time being made self-conscious of how this very process is structured for us cinematically, producing a moment of experimental thinking that provides a philosophical challenge to conventional subject-object arrangements.

One would have trouble arguing with Beh’s reading of this as an intertextual commentary on the plight of women: Nana is prostituted, a martyr to capitalist patriarchy, forced to suffer for her agency much as Joan’s assumption of a typically male-oriented power to act was depicted as witchery and punished with death.68 While this is the transposition of a discursive argument (similarity of representations) onto a comparison of narrative meanings (similarity of situations), it nonetheless manages to capture the complexity of what is perhaps the film’s one great lapse in connotative obstinacy: the camera’s subject-function is momentarily betrayed by the permission of an image for which it was not the implied source. The presence of Dreyer’s film slips the text out of the camera’s control, and the image is at this moment defined through Nana’s subjective act of spectatorship.

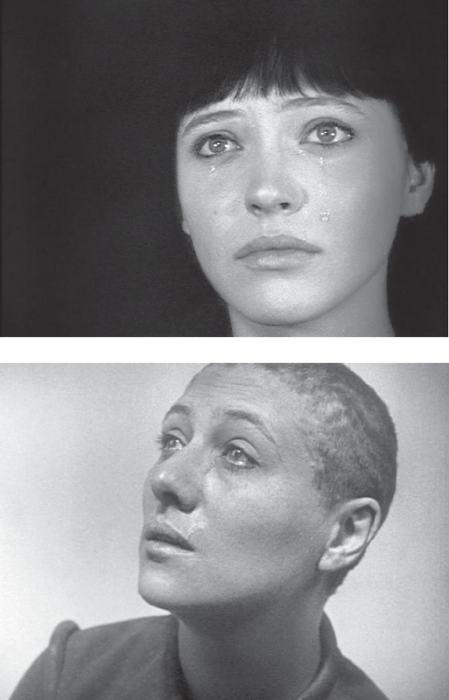

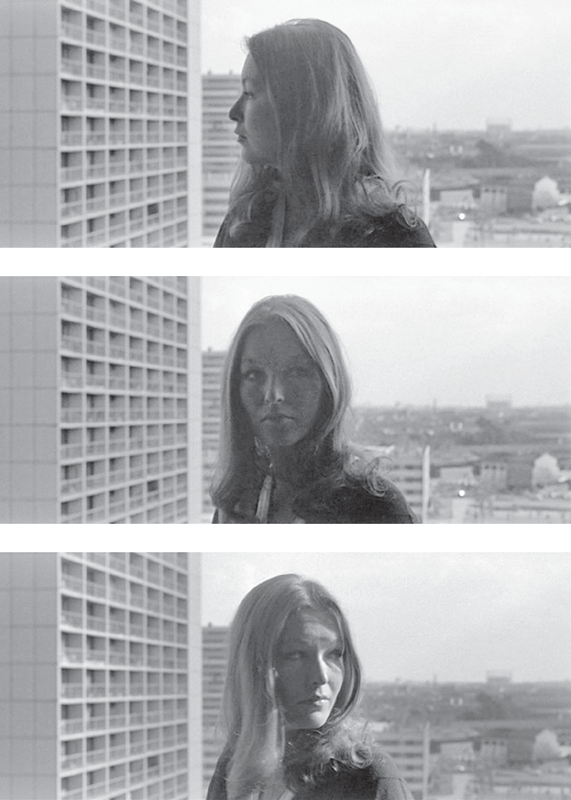

This scene embodies the text’s struggle between a nostalgia for cinema’s early grandeur and a modernist disillusionment with this grandeur, attracting our identification with a representation of spectatorship that also shocks us into a sense of self-awareness or consciousness of the apparatus. Another such challenge to the monolithic, objective system of reference is offered through the point-of-view tracking shot wherein Nana dances around the billiards table. This exemplifies the immediate dialogical shift, possible in cinema, from a subjective (fig. 1.3) to an objective (fig. 1.4) representation, from the perspective of a diegetic subject to that of a transcendental subject, as if Nana’s own subjectivity were being sacrificed so that she might be objectified.

The narrative theme of prostitution establishes this problem for us as a diegetic concern, though this is inseparable from the film’s modes of representation: there is a reflexive similarity between the alienating effect that Nana’s job has on her and the manner through which Godard relates her to the camera, one that has been analyzed according to a psychoanalytic approach that I will not necessarily adopt.69 This particular cut makes a phenomenological connection between the character’s interior view of the world and her external position as an object viewed in that world. For a moment, we are being looked at with Nana, from her perspective, before we go back to looking at her. Unfortunately, this is the extent to which Nana is granted subjective agency in the film, and the formal pretense of ethnographic representation gives way in the end to conventional narrative motivations. Just as is foreshadowed by an overt reference to Poe’s “The Oval Portrait,” Godard ultimately leaves his heroine dead. The film concedes its visual goals and consents to the narrative rule; as Rancière would put it, the rationality of the intrigue ends by dominating the sensible effect of the spectacle.70 The generic cliché through which the film abruptly wraps itself up has been contested as either disappointingly extrafilmic or apt in its intertextual nature. In an otherwise praiseworthy review, Susan Sontag criticizes the end of the film for its sudden abandonment of the enclosed text, through which it is “clearly making a reference outside the film.”71 Beh criticizes Sontag’s analysis for ignoring the intertextual practice of the entire film.72

I read in this debate the film’s attempt to balance itself between the closed text (the film as an object of perception from one stable viewing position) and the open text (dialogic enunciation, Brechtian effects, self-conscious moments of reflexivity). Both critics, however, seem to neglect the fact that this reference to the generic closure of classical gangster films offers no indication that it is more than the invasion of the text by a narrative convention, an argument against overinterpretation that I would support and Godard himself asserts.73 With the high level of film literacy Godard amassed during his decades at the Cinémathèque and as a critic for Cahiers du cinéma, and given the degree of improvisation allowed in his film shoots (ninety-minute films often based on no more than a few pages of script), it is not surprising—nor something that even the biggest fan of Godard should deny—that the director often reverts to a reliance on the type of cliché his oeuvre so successfully deconstructs. This reliance on a generic convention offers the perfect example of a closed cinematic meaning, a circular closure on the film’s origin of meaning.

Overall, the textual system of shot, sequence, and whole in Vivre sa vie weaves a mode of representation common in filmic expression: it implies an objectivity in the representation through the connotation of a total system of reference, that of the camera. In doing so, it embraces a classical epistemology in the Althusserian sense: it arranges a differentiation between source and representation meant to “oppose a given subject to a given object and to call knowledge the abstraction by the subject of the essence of the object.”74 This is the very opposite of Merleau-Ponty’s goal with phenomenology. Vivre sa vie, in all its unconventional stylizations, refers to a connotative system that denies the subjectivity of its viewed objects and, ultimately, closes the production of meaning off to the spectator. But this is, of course, the cinematic norm, the classical and conventional model for the film image. How might these epistemological assumptions be challenged? How could this differentiation be breached? In this film Godard offers certain clues toward such a cinema, a dialogic cinema of being in the world that challenges the hierarchies of conventional representation. Cinema has proven itself curious about, and perhaps even capable of, reconciling the interior with exterior, the subjective with the objective—a possibility of dialogic relations that falls short in Vivre sa vie but succeeds more fully in what remains as perhaps the great moment of philosophical clarity in Godard’s oeuvre: Two or Three Things I Know About Her.

Intersubjectivity in Two or Three Things I Know About Her

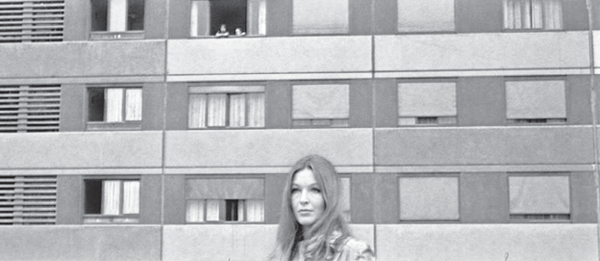

As opposed to the absolute subject of the frame that anchors Vivre sa vie to a continuous system of reference, in Two or Three Things I Know About Her the weight of signification falls to the creation of a dialogic network spread between the frame, the objects viewed, and even voices external to the diegesis. In creating this network, Godard reveals and proceeds to scramble cinema’s conventional division between subject and object, a reflexive mode that demonstrates “how questions about the institution of cinema are immediately posed by a consideration of the object.”75 This film, in other words, formulates the problem of differentiation and agency as an inherently cinematic problem of the immanent field. Here, as in Godard’s oeuvre in general, “consideration of the object” is extended to the consideration of woman-as-object, metaphorized by the social institution of prostitution. This time the story is of Juliette (Marina Vlady), mother of two, living in the tenement suburbs and being forced into prostitution by the economic demands of late capitalism. Trading the classical black-and-white composition of Vivre sa vie for a flattened color image, this film, as MacCabe and Mulvey point out, “marks a move away from the exotic perception of a woman’s selling of her sexuality present in Vivre sa vie and A Married Woman.”76 The term exotic perception can be attached to the Althusserian notion of epistemology previously described, a kind of colonizing of the other inherent to the differentiation of the viewing subject and viewed object, a differentiation contested in this film.

The title itself, in all its ambiguity, introduces many of the film’s themes. First, with “Two or Three Things” there is the notion of itemization, presented in the film in three forms: narrative itemization of the banal rituals that make up daily life (washing dishes, preparing for bed, etc.); itemization of the ubiquitous signs of consumerism, epitomizing the proto–pop art themes contemporaneously prevalent in works such as Roland Barthes’s Mythologies and Georges Perec’s Things;77; and, most important here, itemization of subjective experience through the sequential representation of context provided by the film’s patterns of montage. Furthermore, there resides in the title the nondescript dynamic between speaking subject-function (“I”) and the Paris of 1966 (“Her”) that is known by this subject. This enunciating “I,” vocalized by Godard’s voice-over commentary, is constantly revealed to lack any totality of perspective. It is the subject of the frame, revealed and therefore displaced as just another part of the dialogic field constructed by the sequencing of shots. The rejection of a single coherent source of meaning, I will argue, is constantly “emphasized by the dissociation of sound and image and the increased use of montage.”78

This film, as may already be clear, utilizes a radically different visual dynamic from that of Vivre sa vie. Immobile nearly the entire film, the camera of Two or Three Things I Know About Her does not duplicate or mimic human perception through depth-of-field or acts of movement, yet the frame is also rendered incomplete. The viewing subject is frustrated, but there is also no qualitative idea, building through the montage of shots, that would connote a transcendental subject. A visual design belying Godard’s affinity for documentary television, the frame creates little blocks of static meaning that interact with one another through the construction of a common context: Paris and its surrounding area. The juxtaposition of images offers us a mutual space shared by person, material object, and system of representation. This visual structure respects the notion, as Merleau-Ponty observes, that the world (like the cinematic image) is an immanent field of interaction, “not only the sum of things that fall or could fall before our eyes, but also the place of their compossibility.”79 Contrary to the human condition explored in the existentialism of Sartre, Merleau-Ponty insists that the role of the philosopher extends beyond the individual, to the shared space of meaning created between us, which is where we move beyond the concrete and into the symbolic: “The question is to know whether, as Sartre maintains, there are only men and things, or whether there is not also this interworld which we call history, symbolism and the truth remaining to be accomplished.”80

This is the philosophical—or, specifically, phenomenological—project at play in Two or Three Things I Know About Her; as Godard puts it in an article he wrote while shooting, the film’s goal is to arrive at a representation of the “ensemble,” the relationships between things.81 In terms of my attempt here to understand how this philosophical foundation is transposed onto the connotative plane, this ensemble could be seen as a reduction of the film to its immanent field of relations. Keeping true to the director’s word, this film achieves what Vivre sa vie could not because it acknowledges other subject-functions than that of the camera. Two or Three Things I Know About Her combines a variety of systems of reference that Godard enumerates under four categories, which he could not have phrased more aptly for this study: “objective description of objects,” “objective description of subjects,” “subjective description of objects,” and “subjective description of subjects.”82 Godard makes clear here, in explicitly Merleau-Pontian terms, his desire to break down the conventional subject-object dynamics of cinema and to reconfigure them according to a philosophical model, which necessitates a shift in the hierarchical relationship between form and content. Taking this ensemble further, one could argue that a nonnarrative system of montage predominates within the frame (colors, shapes), between individual shots, and also between the frame and what is offscreen. What lies outside the frame, be it an object in narrative space (Juliette’s reference to clothing that the spectator never sees but is part of the open diegetic space) or an anonymous voice-over (the “I” that knows two or three things, spoken from behind the camera), persistently makes its presence known, creating a dialogism in which the frame is no longer the delimitation of the film’s message.

Two or Three Things I Know About Her arrives thus at a juxtaposition between presence and absence, seen and unseen, a confession of the arbitrariness and partiality of any representation—a balance between what Merleau-Ponty might refer to as the “visible” (sensory world) and the “invisible” (meaning).83 This critique of the shot bears the influence of Dziga Vertov’s paradigm of montage, or “montage of ideas” as Mitry calls it, which denies any predetermined narrative mode of subject positioning.84 The Vertovian source of viewing is intrinsic to the phenomenon of the visible that it reconstructs for our regard, and reproducing this cinematically cannot occur through only a single shot. Its mode of perception, Jean-Philippe Trias notes, is an “atomized perception”85 and is therefore not comparable to human perception, refusing the implication of an absolute system of reference and rejecting the analogy of a camera-consciousness. Deleuze and, later, Rancière observe that this notion of the shot’s relation to montage, as opposed to that of Bazin or Eisenstein, is an attempt to place subjectivity within the transformative process of the moving sound-image, within the immanent field, and not according to one signified position of perception or one overall qualitative meaning, thus implicating the subject in the symbiotic creation of meaning on equal terms as the object (or other subjects).86 Through this, Godard claims not to want to uncover a universal truth but to reveal a contextualization that binds people with their objective surroundings, not some “global and general truth, but a certain ‘feeling of the ensemble.’”87

For example, we see a macrocontext, followed by an interview with a person who functions within that context, followed by a brief scene in the microcontext where that person was interviewed. These shots are audiovisual fragments that form a sequential logic or order of meaning that, instead of constructing causal narration or economy of action, weaves a portrait of people’s coexistence with their surroundings, an expression of the “totality of experience” that is, according to David MacDougall, the goal of ethnographic film.88 This “totality of experience” is integrated into an overall textual network of signification that attempts to reveal what Merleau-Ponty calls “singular existence,” wherein one hopes to describe a specific person’s experience not only by watching her (as in Vivre sa vie) but by letting her speak and by revealing her relationship with everything around her.89 This notion of contextualization, however, is of more interest to my argument as a question not so much of the content, which I believe Godard is referring to, but of the immanent field provided by the formal organization of this content.