When the cabinet meeting began at 2 p.m. on Saturday, Prime Minister Rabin and Defense Minister Peres expected it to be short, since both of them supported the operation. But the debate went on far longer than they’d anticipated. After Chief of Staff Gur presented an outline of the operation, one of the ministers asked: “How many casualties do you expect?” Gur said it was difficult to predict, but that, based on the simulation the night before, he thought the mission would probably succeed. The losses were likely to be low, but there was a chance that as many as twenty hostages would be killed.41 And, Gur admitted, one could never know what would happen in a military action. Success depended on absolute surprise. If the terrorists had even one minute’s warning, they could kill all the hostages with a few grenades and some bursts from their AK-47S, and when the troops arrived, there would be no one left to save. Furthermore, the force would go into action at a distance of a good many hours’ flight from Israel. With a hitch of any kind, there was definitely a risk that not one man in the whole force would come home. And the men who were going, Gur stressed, were Israel’s finest.

Gur’s remarks had an effect. A long, exhausting debate began, with many questions asked and many reservations voiced.

Without a doubt, it was one of the toughest decisions an Israeli government had ever faced. Rabin made it clear that if the raid failed, the government would have to resign. But when the final vote was called, all hands were raised in favor. Only two days had passed since the cabinet had voted, also unanimously, to give in to the demands of the PLO splinter-group holding the plane. The new decision had been made by the cabinet as a whole — but the ultimate responsibility' rested on Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin.

At 3:30 p.m., more than an hour after the force put down at Sharm alSheikh, word came to go forward with the mission. In fact, the cabinet had not yet reached its decision, but in order to keep to the timetable, the order had been given to set out. The force could still be ordered home if the cabinet decided against the operation.

Yoni informed the Unit’s men that they were taking off. “We’re going to do it,” he told them, as the roar of the just-started engines drowned out his voice.

“Yoni went around and told the men, who were surprised to hear they were actually going,” says Shlomo. “Not that he was raring to fight, but he didn’t look at all worried by the go-ahead either. You could see that he felt very comfortable, that he was finally starting to breathe easy.” Others had the same impression: Yoni was relaxed and buoyant from the moment the order was given, and stayed that way throughout the flight.

Among the men the general feeling was very positive, though not free of anxiety. They had felt confident even before, when they boarded the plane at Lod, but the feeling now grew much stronger. They believed in their ability to carry off the mission. “When we left Sharm al-Sheikh, I had a good feeling, that I was prepared for action. I don’t remember any fear, even in the back of my mind, that I wasn’t as ready as I should be,” says one officer, who only twelve hours before, after the simulation and a harried day of preparations, had gone to sleep with a nagging fear that the Unit wasn’t ready for the operation. And another officer, who had talked the night before with friends about how to keep the mission from being approved, says: “When we boarded the planes, we were extremely confident, and this confidence had been inspired, first and foremost, by Yoni.” The men did not doubt any more that they would succeed in freeing the hostages. The only thing that still worried them was whether they would be able to get out of Entebbe. The possibility that they might be stranded in Africa, thousands of miles from Israel, didn’t leave their minds.

The troops were told to hurry on board. To maintain secrecy, Yoni hadn’t wanted the members of the assault force to put on their camouflage fatigues before they reached Sharm al-Sheikh, and on board the plane, he thought, it would simply be too crowded to change. Bukhris recalls that they stood on the runway, quickly pulling off their regular olive-drab uniforms and putting the mottled ones on.

At that moment Shomron passed by and started yelling: “What are you guys doing now? Who needs this nonsense?”

They finished dressing without responding to his shouts. “He was talking about our ‘nonsense’ when the whole operation depended on the ruse, which we kept our mouths shut about,” says Bukhris. “When you’re about to go out on a mission like this, and suddenly an officer of that rank starts yelling at you, and about something that small that you need twenty seconds for.. .it really left a lousy taste in my mouth.”

The four planes were loaded much more heavily than was permitted in training, and possibly more heavily than any Hercules transport had been loaded before. The fuel tanks were absolutely full, including the wing tanks. Besides the air force flight crew, Shani’s Hercules One carried the Unit’s assault force of 29 men and its three vehicles, as well as 52 paratroopers and part of Shomron’s command team.

Hercules Two, Nati’s plane, may have been even heavier. It carried two of the Unit’s APCs and their 16 troops, Dan Shomron’s command jeep and the other half of his team, and 17 more paratroopers.

Hercules Three, piloted by Maj. Aryeh, carried the Unit’s other two APCs and their men, along with 30 Golani fighters and their jeep.

On board Hercules Four, Halivni’s plane, were two Peugeot pickups, one for the Golani contingent, and the second to transport the fuel pump. The plane also carried the pump itself, the ten members of the refueling crew, the ten-man medical team, and twenty more Golani soldiers.

The runway at Sharm al-Sheikh lies across a low hill, making it impossible to see the end while the plane is accelerating for takeoff. The Hercules was designed for improvised battle-field airstrips, and the pilots were used to making short takeoffs. They were unpleasantly surprised. The planes gained speed with great difficulty, and to the men at the controls, it seemed that the runway would end before the planes got off the ground. Making matters worse was the 100-degree desert heat, which cut the power of the engines by as much as a third. The trip down the runway, heading northward against the wind, seemed to last forever before the planes finally gathered enough speed to lift into the air.

After his plane had gained altitude, Shani wanted to turn around and begin heading south, but he found he couldn’t. He was flying only two or three knots above the velocity at which the plane would stall, spin out of control, and crash. The Hercules refused to pick up speed, and every time Shani tried to make the turn, it began to shake, forcing him to straighten out again to keep from endangering the plane and its load. “No responsible pilot has ever handled an aircraft under such conditions,” he says.

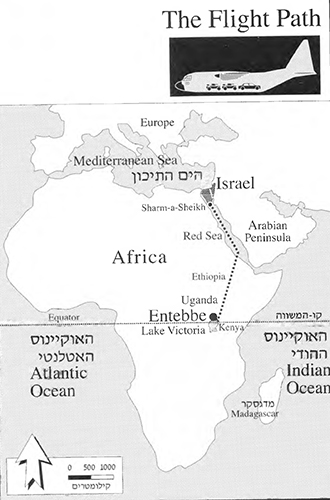

After a while the planes stabilized and made the turn southward towards Africa without mishap. They flew the length of the Red Sea only about 200 feet above the waves, to avoid Saudi radar on the east and Egyptian radar on the west. Still, the flight was considerably more comfortable than the previous one, because fewer air pockets form over water than over land. When the planes’ radar detected a passing ship or the crewmen sighted one themselves, they swung as far away from it as possible, so no one below would notice the four military aircraft heading southward. That caused repeated deviations from the planned flight path, and each time it took careful navigation to return to the right course. In the daylight, the planes’ pilots could still follow each other by sight, but when night fell they would have to manage with radar alone.

The flight path followed the narrow strip of sea a long way. The planes would stay at low altitude until reaching a certain set of coordinates, where they would begin climbing and turn southsouthwest toward Ethiopia. Ethiopia had no radar that could effectively track combat aircraft at night; once there, they would be able to fly at 20,000 feet, which would require less fuel.

In the belly of Hercules One, the soldiers were packed together with barely any room to move. The paratroopers were crowded between the vehicles and the sides of the plane. The Unit’s men had the middle, which meant sitting in or on the vehicles, lying on the floor under them, or sprawling out on the hoods of the cars or the roof of the Mercedes. It was quiet; the soldiers spoke only a few words to each other. For the most part, each was lost in his own thoughts, at times peering out the windows at the blue water and the shoreline where the Saudi Arabian desert met the sea.

Wedged between the front of the Mercedes and the plane’s rear cargo gate, Yoni and Muki explained to Amos Goren his role in the mission. All three sat leaning against the gate. Amos, who had been added to the assault force at the last minute to replace the soldier who had gotten sick on the first flight, was only vaguely familiar with the layout of the terminal and the tasks of the various teams. Yoni sketched the plan of the terminal and the assault routes on the back of an air sickness bag as he spoke. No matter what happens, he and Muki told Amos, he should stay right behind Muki.

“At exactly the moment when Yoni was explaining all this to me, we were informed that the government had given us the green light, that we were going to do this… Yet he stayed completely calm.. .and went on explaining my job to me as though we were going to do an exercise.”

The private briefing lasted about twenty minutes. When it ended, Amos took the bag, and after looking it over again, folded it up and put it in his pocket.

Yoni and Muki climbed into the Mercedes. They sat in the front seat, and Yoni took the book he had brought with him out of his pocket and started to read. He usually read when he was forced to wait for something, which was why he’d brought the book. But he probably also knew the effect it would have on the men, who would see that he, at least, wasn’t tense. When he read one passage, he laughed to himself and said to Muki in mock admiration: “Listen, these are real men. What are we, compared to them?” Then he noticed Amitzur standing in front of them, fixing the way the Ugandan flag on the front of the Mercedes looked. “He’s a boy wonder, Amitzur is,” Yoni said to Muki with affection. Afterwards, Amitzur sat down in the Mercedes for a little while and talked with Yoni. They spoke “a little about life,” Amitzur recalls, “and Yoni talked about what we were about to do, and how important it was.”

A little while later, the plane hit turbulence. The Mercedes was bouncing up and down, and everyone got out. Yoni went forward to the flight deck, maneuvering his way over the vehicles.

The normally roomy flight deck was crowded to the limit with officers. Most were sitting on small wicker stools. Shani sat up front in the pilot’s seat, with Einstein to his right in the copilot’s place. Immediately behind them were the navigators. Rami Levi, the El A1 pilot who had been attached to them, was looking over the Jeppesen guide. He was the one who was supposed to speak with the control tower at Entebbe if the need arose, and wanted to get his story straight. After examining the various airports in East Afriea-in the guide, he decided that it would be best to pose as a small Kenyan aircraft, taking off from Kisomo Airport in Kenya near the Ugandan border. Rami rehearsed the words he would use. Afterwards, he sat down on the floor of the plane with a map of Uganda spread out beside him, and passed the time preparing the flight pattern for the descent.

Einstein asked that someone pass him a piece of cake. The custom was for the load masters to provide food for the crew during the flight, since they had little to do once the cargo was loaded on board. And indeed they had put a cake on a tray at the back of the flight deck, and Yoni, who was sitting next to it, passed a piece up to Einstein. But the copilot sent it back, calling to Yoni: “No, I want a moist square from the middle, not one from the edge.”

Yoni smiled and quipped: “Are these pilots ever spoiled! Poor things can’t eat from the edge of the cake.” He sent up another piece, and had some himself.

From time to time Yoni and Shomron would ask the navigator questions about their precise position and flight path. Shani conferred with Shomron and Yoni, and they agreed again that they would land no matter what, whether they found the runway lighted or dark. They both gave Shani full backing for his plan of pretending to be the pilot of a plane in distress if the lights were out. Yoni studied the new aerial photos yet again, and also went over a number of points with Shomron and Lt.-Col. Haim Oren of the Infantry and Paratroops Command, including the exact time at which the two would arrive in their command jeep at the old terminal.42

Yoni also spoke a bit with Matan Vilna’i, who was on the flight deck too. The two knew each other not only from the army, but from growing up in Jerusalem. In 1968, when he was studying at the Hebrew University and trying to decide whether to go back into the army, Yoni had gone to Vilna’i to ask his advice. “What would you do?” he asked. “Should I go back to my paratroops battalion and be a company commander, or should I go to Bibi’s unit?” Vilna’i, who was then in the paratroops, answered without a moment’s hesitation that if he were in Yoni’s place, he’d choose the Unit. And within a few weeks, Yoni joined the Unit as a junior officer. Nearly eight years later, now the Unit’s commander, he stood with Vilna’i on the flight deck of a plane heading south over Africa.

Yoni now talked with Lt.-Col. Haim Oren, whom he knew from their joint service in the Haruv commando unit. At one point in the conversation, Yoni said: “If he’s there, I’ll kill him.”

“Who are you talking about?” asked Haim.

“Idi Amin,” said Yoni.

Haim was stunned. He urged Yoni to banish the thought from his mind, but his pleading fell on deaf ears. “You can’t do something like that. It hasn’t even been discussed. You’d have to ask for approval,” Haim said.

“I don’t intend to ask. If Idi Amin is there, I’m going to kill him,” said Yoni, without offering explanations. From Yoni’s point of view, the reasons were self-evident.

In a letter he had written to Tutti seven years before, he had said: “What an insane world we live in! In the twentieth century we’ve landed on the moon, and there’s still more to come. But the twentieth century has also seen Hitler and his mass murders. And it saw the horrors of World War I. Yet we still haven’t learned. Today we’re seeing an entire people being wiped out by starvation [in Biafra], and still no one is concerned enough to get this ugly world to do anything about it. All of us — including Israel, including me — are caught up in our own wars, and there’s not a single country willing to go in with its army and stop what’s happening there. Of course not. No one wants to get involved. What strange animals people are.”43 Now he had firmly decided that if he saw this monster of a man named Idi Amin, who’d murdered hundreds of thousands of his countrymen, and who threw the victims of his torture chambers from the top floor of Kampala’s fancy Nile Hotel, he wouldn’t let him get away alive.

In the rear of the plane many of the men had dozed off, overcome by both the accumulated exhaustion of the week and the drowsiness induced by the anti-nausea pills. But many others couldn’t fall asleep. Some busied themselves with simple tasks like checking their ammo vests or aligning their sighting lights yet again in the relative darkness of the plane after nightfall. Otherwise, there was little to do but sit and think about what was coming and what one had already done in life. Bukhris sat the entire time in his place in the jeep, wearing his ammo vest and rifle, his machine gun at his side, studying the faces of the soldiers around him.

Amir also did not shut his eyes for a moment, even though 2½ days had passed since he’d last slept. “We were flying, and at a certain point we realized that we just weren’t turning back, that we couldn’t even if we wanted to, because there wasn’t enough fuel. A lot of guys went to sleep… but I didn’t manage to sleep the whole flight, not for a second. The whole time I was thinking and repeating over and over what I was supposed to do and how I was going to do it. I wasn’t shaking with fear, but I was very tense.”

Sometime during the flight, Muki called Amir and Amos over. The two had been assigned to handle the bullhorns, and Muki discussed with them what exactly the hostages should be told. They decided once again that, at the moment of battle, the captives should simply be instructed to lie flat on the ground.

Shlomo dozed on and off. At one point he woke up and walked around the plane to stretch his legs and see what was happening. When he spotted Yoni sitting in the Mercedes, calmly reading his book, he thought to himself that this was something really special. Surin from the paratroops, who was sitting beside the car, was surprised that Yoni was reading an English book. Like most of the men around him, Surin was also unable to fall asleep — in large part because conditions were simply too cramped. Every time Surin wanted to straighten his legs a bit, he had to stick them under the Mercedes. It’s not easy to fall asleep, he found, with a car bouncing up and down above you, coming within inches of your legs.

After a few hours, Yoni wanted to go to sleep. In the rear of the flight deck, there were two narrow cots stacked as a bunk bed. The bottom bed was broken, but the top one was intact and unoccupied. Shomron, who could see that Yoni was tired, told him: “You can have the bed. You sleep on the way there, and I’ll sleep on the way back.”44 Yoni asked the navigator to wake him up half an hour or so before landing. He pulled a blue inflatable pillow from one of his pockets, blew it up, climbed onto the top bed, put the pillow under his head, and fell asleep almost immediately.

A little while later, Shani also wanted to go to sleep. Several hours were left before the landing. “I look back and see Yoni sleeping in that bed,” says Shani. “Under normal conditions, if some battalion commander is resting there, I tell him politely but firmly to go rest in the rear of the plane. This time I couldn’t bring myself to do it, because my theory was that the first group that storms that building, its chances of staying alive are fifty-fifty. I said to myself: He’s taking a huge personal risk in this, that’s for sure. He’s grabbing some sleep here. So am I going to wake him up? On the other hand, I also wanted to lie down. He was curled up on the edge. I lay down next to him, getting closer little by little till I was a few millimeters away from him.”

Lying there, Shani closed his eyes, but they snapped open a minute later. He felt the weight of the responsibility he bore, and he could feel his heart pounding rapidly. Would he manage to land without trouble, he asked himself, or would he have to make several passes over the airport before he could put the plane down? In that case would the entire airport be awakened, the terrorists alerted, the hostages killed? Because of his failure to land the plane, would they be ordered home without carrying out the mission? Variations on these questions kept repeating themselves in his mind.

“I was afraid of a failure on the national level — not just that someone would be killed or wounded, but that we simply wouldn’t succeed, that we’d cause a disaster,” explains Shani. Gur’s words from the day before — that responsibility for the operation’s success rested with the pilots, since as Gur put it, it didn’t make any difference to the Unit’s men whether they were put down in Tel Aviv or Entebbe — echoed in his ears.

“I looked at Yoni from about an inch away, nose to nose, and he was sleeping like a baby, utterly at peace. I asked Tzvika, the navigator, when Yoni had gone to sleep, and he said, ‘Listen, he went to sleep and said to wake him up a little while before the landing.’ And I couldn’t free myself from the thought: Where does this calmness of his come from? Soon you’re going into battle, and here you are, sleeping as if nothing’s happening! I got up and went back to my seat.”45

After Shani got up, Rami Levi decided that he needed to stretch out. He moved Yoni a little in order to clear himself a place to sleep. "He turned over a bit, and went on sleeping. I lay down next to him to rest a while; I knew I wouldn’t fall asleep. I didn’t know who Yoni was. I just saw a lieutenant-colonel in a camouflage uniform lying there, tired. I didn’t know that he was the commander of the Unit, but I’d seen him on the flight deck. He was in charge of something, so it seemed to me. Now I said to myself: ‘These guys probably haven’t slept in days.’ I remember this thought going through my head: And who knows if these aren’t his last hours of sleep, maybe ever.”

They woke Yoni when the plane was already nearing Lake Victoria. Most of the flight over Africa had been through Ethiopian airspace. From time to time, the pilots reported their locations, using code words signifying designated points on the route.

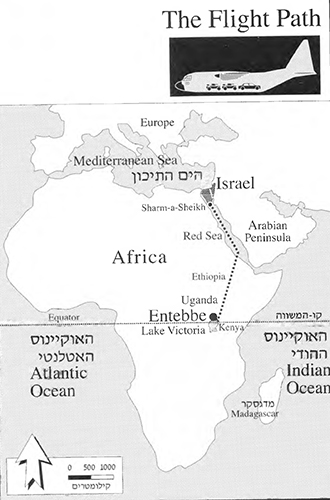

The planes crossed the border out of Ethiopia over the huge Lake Rudolph, and continued south-southwest over the western reaches of Kenya. Despite their altitude, the high African clouds remained well above them, dropping rain on the planes now and then. On the radio, they heard the exchange between the Entebbe control tower and the pilot of a British Airways jet as it took off from the airport, exactly on schedule. At around 10:30 p.m. Israel time, they reached Lake Victoria, flying over the bay near the Kenyan town of Kisomo. They now ran into extremely stormy weather, and the static electricity in the highly charged air sent bursts of light dancing across the windshields of the planes. Here three of the planes circled downward in the storm for about six minutes, hanging back to give the assault force time to carry out the primary action.

Hercules One flew on alone over Lake Victoria. Its flight path first took it westward, toward a large island south of Entebbe. From there it would be able to fly due north to the airport. Contact was now made for the first time with the Boeing 707 command plane that had caught up with Hercules One and was circling above. Here, out of radio range from Arab countries, they could speak Hebrew freely, without any codes. “Do you see the runway lights?” Peled asked Shani.

“Not yet,” Shani answered.

As they flew through the storm over Lake Victoria, Yoni went back into the hold of the plane. Some of the men were still asleep. Yoni went around waking them up and telling them to put on their ammo vests and prepare for landing. Giora, who was dozing in the Mercedes, recalls that Yoni had a smile on his face when he woke him up. Yoni bent down to wake up Amitzur, who was asleep on the floor of the plane under the car. Shlomo pondered the perennial soldier’s question of how many layers of clothing to wear — the storm outside told him nothing about whether it would be hot or cold in Uganda. Alik, who had slept for most of the flight on the hood of one of the jeeps, felt very hungry when he awoke. He had not eaten any of the food they’d been given at Sharm al-Sheikh, and now he went up to the flight deck to find something to take the edge off his hunger.

Rani Cohen, a young officer on Yiftah’s team, had also been sleeping since the flight began. When they had taken off from Sharm al-Sheikh, word had not yet come that the raid had been approved, and Rani had gone to sleep, serenely certain that the order would soon come for the planes to return to Israel. When he awoke, he suddenly discovered he was about to land in Uganda. It was the first time that he had felt any tension whatsoever. He peered out a nearby window. The storm was already behind them, and the star-strewn sky lit the waters of Lake Victoria below. Rani went back to where he’d been sitting, went over in his mind the sequence of the actions the force would execute, and tried to envision the structure of the old terminal and its entrances.

The soldiers took their places in the vehicles. The landing approached, and the excitement among the soldiers reached a peak. Yoni now did something that none of them had ever seen before any other operation. He moved along the row of vehicles, walking on the jeeps, going from soldier to soldier, officer to officer, and with a word, a smile, an occasional handshake, encouraged his men.

“There was this reddish light, and I remember that we saw his face,” tells Shlomo. “He wasn’t wearing his beret, or his ammo vest or gun… He spoke to all the men, .smiled at us, said a few words of encouragement to each one. It was as though he were leaving us, as though he knew what was going to happen to him. He didn’t issue any orders, but just tried to instill confidence. I remember that he shook hands with the youngest guy on the force… He acted more like a friend… I sensed he felt that from here on everything, or at least nearly everything, depended on these men. He’d seen a lot of combat, and quite a few of the soldiers there had seen none at all, or a lot less than he had. And I remember him going by, joking a little, exchanging a few words, easing the men’s tension before battle.”

“Remember,” Yoni told them, “that we’re the best soldiers who’ll be there. There’s nothing for us to be afraid of.”

When he reached Arnon, he shook his hand and said, referring to the terrorists: “Don’t hesitate to kill those bastards.” He also shook hands with the men on his own team — David the doctor and Tamir the communications man. “It'll be all right ,” he told Tamir. “Well do it without a hitch, don't worry.” At the very back of his jeep, to the left, sat Bukhris. “What are you smiling about, Bukhris,” Yoni said when he reached him, tousling the shock of dark hair on the young soldier's head.

“It created a sense of personal connection between him and all of us, the men who'd be doing the fighting,” says Bukhris. “It's not like some commander way above you who hands down orders to the officers under him, and they pass the orders further down, until you, the grunt, can't even see the top of the pyramid. Yoni gave this feeling of a personal tie between the commander of the operation and the very last soldier in the force, which, in terms of age, was me. That encounter, right before we landed, left me with a very, very good feeling.”

One of the officers of the Unit went over to Yoni and said: “Don't stay too near the assault force. Remember you’re the commander of the Unit, and you can’t be hit.” Yoni smiled at him, and said: “It’ll be all right.”46 Then he shook hands with Muki.

Yoni went to the flight deck for a moment. The storm was behind them, and the sky was clear. Up ahead, it was already possible to see the runway lights at Entebbe. The strip was brightly lit for all to see, while the plane, flying without lights under cover of the darkness, was invisible from the ground. When the men on the flight deck saw the shining lights, there was a general feeling of relief — apparently no one was expecting them there. Shani carefully continued bringing the plane down. It could not touch down too hard, lest its excessive weight cause the landing-gear tires to burst. Meanwhile, the crew also carried out the routine for a radar landing, so that if the Ugandans suddenly suspected something and shut off the lights at the last minute, Shani would still be able to try to land the plane.

“Everything all right?” came Benny Peled’s voice from the airborne command center.

“A-OK,” Shani answered, carefully keeping the excitement in his voice under control because he knew he was being recorded. “No problems.”

From the flight deck, Yoni — along with Shomron and Vilna'i — examined the airport ahead. To the right of the runway was the new terminal, also lighted. Further away to the east was the old terminal, less distinct, though the lights were on there too. Yoni quickly returned to his men, and, after putting on his ammo vest, climbed into the front seat of the Mercedes. In front of him was the rear door of the plane. To his right, next to the window of the car, now stood Matan Vilnai, who had left the flight deck after him. Matan positioned himself near the side door, through which his paratroop commandos would leave to place the back-up lights on the runway.

The rear door now began to open, even before the plane touched down, and Yoni could see the black waters of Lake Victoria. He told Amitzur to start the Mercedes. The starter, which had been repaired at the Unit's base, did its job, and the engine came to life. Seconds later, they felt the jolt of the plane hitting the ground and could see the runway lights racing past them. Bukhris glanced at his watch. It was 11:01 p.m. Israel time — just after midnight on clocks in Uganda, the beginning of July 4,1976.

The plane quickly cut speed. When it reached the middle of the runway, the ten soldiers of the paratroop commando team leapt to the tarmac, one after another, as the plane continued moving toward the Unit’s deplaning point. At the same time the straps tying the vehicles to the floor of the plane were released.

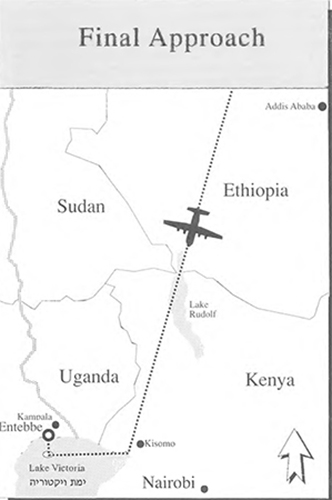

Shani taxied to the access strip connecting the main runway to the diagonal, turned to the right, and brought the plane to a halt. He had delivered the Unit’s assault force to its starting point.

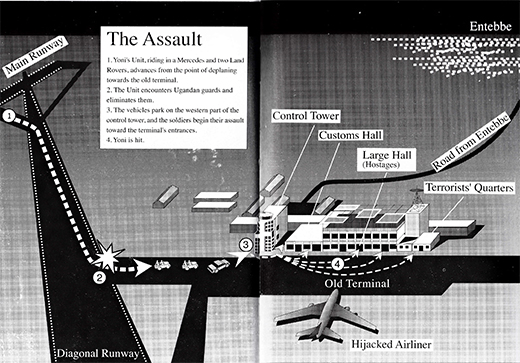

The signal was given to lower the ramp all the way to the ground. Before it had even settled properly on the asphalt, the Mercedes had already pulled out and turned right, alongside the plane, with the two jeeps behind it.

“I saw them pass under the wing,” says Shani. “The access strip was rather narrow, with a ditch running next to it, and I was afraid they were driving too close to us, and in a second the propeller was going to slice through the roof of the Mercedes. But they got by, and the three vehicles headed down the access strip and disappeared from sight.”

After the Mercedes had moved a little away from the plane, Yoni turned around to make sure that the two jeeps were following. He ordered the soldiers sitting in the back seat to maintain visual contact with them, and told Amitzur to keep going. They kept to 40 miles per hour, the speed to be expected of someone driving innocently across airport. Near them to the right, beyond a level field, was the new terminal building, awash with light. They were pulling away from il now and made a right onto the diagonal runway leading to the old terminal area.

The rumble of the plane’s engines, which had accompanied them through the long hours of the flight, quickly faded behind them. Near-silence descended; all that could be heard was the hum of their own engines and the whir of the wheels on the asphalt. The air outside was heavy with a warm, tropical humidity. The feel of the air, along with the high grass by the sides of the runway, through which the men could see anthills as tall as men in the glow of the headlights, brought home to them that they were in a strange, unknown land. But those, like Amir, who had allowed their imaginations to portray Africa as something exotic, a land of lions and crocodiles, now found themselves in a surprisingly mundane scene, remarkably similar to every other airport in the world, including the one they’d left at Lod.

Yet they were not at Lod, but in hostile territory, exposed and visible to anyone who bothered to look, and protected to no small degree by the very unexpectedness of their presence there. In his seat in the jeep, Ilan felt as though he were trapped and exposed by the burning headlights of his own jeep, which announced his presence to the world and lit up the vehicle in front of him. Next to him sat Amir, who looked at the men around him as the distance between them and the objective grew smaller and wondered: Which of them will still be standing on his feet five minutes from now? Shlomo sat in the same jeep. He now picked out at a distance the dim lights emanating from the old terminal area, and strained his ears to hear any sounds. As one accustomed by experience to recognize the sounds of gunfire and explosions as harbingers of trouble, he expected to hear at any moment the telltale shots marking the beginning of the massacre of the hostages. But for now the silence remained unbroken.

It took about a minute to reach the approach road that led to the old terminal. Amitzur signalled left before turning the wheel and pulling onto the road. It was important to nurture any seed of hesitation among the Ugandans who might be hidden in the dark, beyond the headlights of the car, so that they would not open fire and delay them. The si1houette of the high control tower even closer to them, grew ever larger.

Suddenly, two Ugandan sentries appeared, standing on the approach road in the headlights of the Mercedes, one on the right side and the other on the left. Through Bukhris’ mind flashed the image of the two “sentries” Yoni had posted in exactly the same place the night before during the simulation, and at that moment he knew: The mission would succeed.

The sentry on the left vanished back into the darkness, while the one on the right advanced toward the Mercedes. He now acted precisely as Amnon Halivni had told Yoni he would that morning. After stamping his foot and calling out a warning, the sentry raised his rifle to his shoulder and aimed it at the Mercedes. The metallic noise of a rifle being cocked could be heard. It was obvious to almost everyone that the sentry had assumed a menacing pose and was demanding that the vehicles moving towards him stop and identify themselves — or he would shoot.47 “I was sure the guard was about to fire,” says Rani, “no ‘ifs’ about it.” The Mercedes was about twenty yards from the Ugandan. Yoni instructed the men sitting next to the windows to ready pistols with silencers for action. It was for just such a turn of events that they had prepared at the Unit. “The guard had to be taken out,” explains Amir. According to the script, they were first to try to solve the problem, if possible, with silenced fire. “Yoni was calm,” recalls Amitzur, the driver. Yoni told him to approach the sentry on the left-hand side, and to slow down. The order was intended to reassure the sentry that they were indeed approaching him to identify themselves — and probably also intended to enable them to shoot more accurately. They closed in on the dark form of the soldier, who continued to aim his rifle at them. At the last instant, Muki shouted “Don’t shoot!” not believing that the Ugandan would actually fire on them.* But Yoni had no hesitation about what had to be done. As the Mercedes passed within a few yards of the sentry, Yoni gave the order to fire. The sentry looked surprised by what was happening. Both Yoni and Giora, who sat behind Yoni next to the right-hand window, opened fire with silenced pistols they thrust out the windows. The sentry staggered back and tottered. But even of the bullets had actually hit him, lie was apparently not out ol action.

The stillness was suddenly shattered by open, unsilenced fire. The source of the burst cannot be determined for certain; it may have come from one of the Israeli vehicles, or, according to some ot the men, from the sentry who had been fired upon, or even from some other Ugandan soldier. In any case, even if it was not the sentry who had first opened unsilenced fire, it was clear he had not been taken out by the pistols, and it was imperative that he be eliminated at once. “One does not leave behind an armed soldier.. .who would use his weapon once he realized what you were going to do,” explains Yiftah. Alex, who was sitting in the right-hand position in the rear seat of the Mercedes, thrust his pistol out the window as well, even though it had no silencer, and began shooting at the Ugandan, whom the Mercedes had passed by now. He fired six of the seven bullets in the clip of his Beretta and believes that the last bullets found their mark. Fire also came from the jeeps. The moment he heard unsilenced shooting, Amnon Peled opened fire with the machine gun mounted on the jeep, intending to finish off the sentry once and for all, as did others in the jeeps. The entire incident, from the first pistol shots to the elimination of the sentry, was over in an instant.

“We could not have approached the terminal building silently any closer than we did,” sums up Amir. “We started shooting heavy fire, and had we not done that, I’m sure they [the sentries] would have fired on us.”

With the first sentry eliminated, the second one reappeared. He was spotted running with all his might, but instead of fleeing into the darkness, he ran away from them on the asphalt, fully exposed, along the lights of the access road. He could not be left behind, since he could endanger the rear of the assault force. Bukhris, who was holding a machine gun in his hands, was given an order by Yiftah to open fire on him. Both the jeep from which he was firing and the Ugandan were in motion, and the first rounds missed the target. But then Bukhris laid a long burst in front of the Ugandan, and didn’t release the trigger until he saw the soldier run right into the flying bullets and fall.

During this seconds-long firefight, the Mercedes had leapt forward. The moment the silence was broken, Yoni told Amitzur to drive on at top speed. They were very close to the old terminal, with the control lower rising in front of them no more than 200 yards away. They covered the distance in a few seconds. As they approached, Yoni probably saw several armed Ugandans in the lighted entrance area of the terminal. It was obvious that the latest aerial photos had been correct and that the massive Ugandan security belt reported originally did not exist. Yoni may have spotted one or more of the terrorists, armed with AK-47S, outside near the entrance to the large hall.* No one opened fire on the Israeli force yet. Yoni quickly read the situation and ordered Amitzur to turn left, before the control tower, and park the car next to it. This was a different stopping point from the one that had been planned, which was twenty yards further ahead, between the tower and the terminal. Yoni’s assessment must have been that in this area, which was substantially darker than the plaza, the force would be less likely to be identified and less vulnerable to attack during the cumbersome process of getting out of the vehicles.

“Stop here,” Yoni ordered Amitzur, and the Mercedes instantly came to a halt, tires screeching. “Leave the engine running,” he said, and jumped out. The jeeps arrived right afterwards and pulled up behind the Mercedes. Men poured out of the vehicles in disorder as Yoni shouted at them to get out and storm the building. Not a single round had yet been fired as the first of them began to move toward the target, only a few dozen yards away. By now, any terrorist who had been outside must have moved into the hall. As the Unit’s men ran, they formed a triangle, at the head of which were Muki, Yoni and others, while the men who ran behind them gave the appearance ol a fan. A number of men were still climbing out of the vehicles. Muki, who ran first, a little ahead of Yoni, fired a few bursts, one or two of which were perhaps aimed at a terrorist who came out of the hall for a second. It seems that one of the terrorists in the hall shouted at one point to his comrades: “The Ugandans have gone nuts — They’re shooting at us!”48 At least for this first moment, the terrorist was fooled by the ruse that had been intended primarily for the Ugandan guards.

Within seconds, the spearhead of the force reached the beginning of the terminal beyond the control tower. Here Muki Betser pulled to the left, toward the corner of the building. He flattened himself against the wall and began firing into the plaza, and the entire force suddenly stopped behind him. Yoni, who was standing to his right in the open, shouted several times: “Betser, forward! Forward, Betser!”49 The delay that would lead to disaster, which Yoni had so feared, was taking shape before his eyes. To Shlomo Reisman, who was further back, the force appeared at that instant, in the dim light, like something strange and awesome — the soldiers crouched, leaning forward, in their mottled fatigues, with the round sighting lights jutting up from the barrels of their guns. “Forward!” shouted Yoni again, impatiently. The loss of a fraction of a second, especially when they were so close to the hostages, could have catastrophic consequences. “We knew,” says Amos Goren, “that it was a matter of seconds before the terrorists would recover their wits” and would start to shoot the hostages.

The delay, though, continued but a few seconds, for Yoni decided to take action himself. Yoni now lunged forward, presumably at the instant Muki ceased his fire, and bypassed Muki. “Yoni kept shouting to run forward, and I remember him running forward and passing Muki,” recalls Amos. “The one who was first out of the corner of the building was Yoni. Then he ran a little to the right, to let the men [who were meant to go inside the building] pass him.” “Once Yoni started to run, those who had hesitated ran too… He pulled the line with him,” says another soldier.50 The fan began moving again. Thus Yiftah, as soon as he saw Yoni begin to run past Muki, and understood what was going on, started running and also passed Muki.51 With another soldier running behind him, he burst through the first entrance of the building, which would lead him to the second floor.

At the same time, Amir arrived from behind, running fast. When he’d climbed out of the jeep, he’d looked for his commander, Amnon Peled, whom he was supposed to follow, but whom he hadn’t seen. Amir was convinced that Amnon was running on ahead of him, and he was afraid Amnon would charge into the building alone. In fact, Amnon had not yet finished extricating himself from the jeep, and was still at the rear. Amir began running as hard as he could, intending to catch up with his commander and reach his entrance as quickly as possible. To avoid being slowed down, he ran to the right and began to overtake the group of men behind Muki, while hearing Yoni’s urgent shouts of “Forward!” Up ahead, he could see the door he was supposed to enter, and he kept overtaking the others. “I didn’t care about anything else. I remembered what Yoni had told us, to run as hard as we could, and I ran as hard as I could.”

Right behind Amir was Amnon, who was straining to catch up with the man who was supposed to follow him. He didn’t even notice that the force had been held up, apparently reaching the edge of the building after Yoni had already passed Muki and the assault had resumed. It can’t be said for certain who passed the edge of the building and entered the lit plaza first — Yoni, or Amir and Amnon. In any case, by the time they were running along the front of the building, Amir and Amnon had almost certainly passed Yoni. Because of his role, Yoni now ran more slowly so he could watch the entire force and check what it was doing, probably turning his head back and to the left to see how the assault was taking shape. “Go in!” Yoni managed to shout while still running forward. Now Muki began to run again, with Amos Goren and another soldier from his team on his heels.

Perhaps about twenty seconds had passed since the cars had stopped. Amir, with his commander Amnon behind him, was first in the line of assault, some distance from the front of the building. After them were Muki and Amos Goren, hugging more closely to the building and running almost parallel to Yoni, who was several yards from the front of the building, in a more exposed position in the plaza. It is possible that Giora, too, had overtaken Yoni and was now ahead of him. The rest of the force had fanned out behind them. With Yoni, about a yard behind him, ran Tamir and Alik, the members of his command team.

At this point or a little sooner, a Ugandan soldier jumped out from behind some crates on the right. He aimed his rifle towards the force and apparently also managed to shoot, He was immediately eliminated by bursts of fire from several soldiers — just as the wide windows of the hall were shattered by gunfire from one of the terrorists, who had figured out what was happening and started shooting through the glass.

Amos now saw, from the corner of his eye, that someone to his right had fallen. It was Yoni. He had been shot in the front of his chest and in his arm, by a burst from an AK-47.52

Yoni had almost managed to reach the point he had designated for his command team to deploy, and may have already slowed down and turned his head to the left to look to check how the force was advancing. At the time he was hit, he was roughly in front of the first door of the large hall,53 and he probably had time to understand that Muki’s team, which was supposed to go through this door, was running past it. Yoni crumpled forward and turned around; then his upper body straightened again. His face twisted, his arms went out to the sides, and his knees folded under him. He sank to the ground, sighing, and sprawled on his stomach.

“Yoni’s wounded!” Tamir shouted. No one stopped to treat him, since his own orders had been that the wounded were not to be attended to until after the assault. The teams continued independently towards their respective objectives — parts of a machine that worked automatically, even without anyone in command, without a word from Yoni, who was lying immobile on the asphalt in front of the hall where the hostages were.

Amir was already opposite his entrance, the second door of the large hall, and had turned straight toward it. One of the terrorists was lying prone on the other side of the door and fired a short burst out of the hall from his AK-47. it may be that the gunman was not aiming at Amir, for if he was, says Amir, “I don’t understand how he could possibly have missed me.” Amir’s memory is of hearing Tamir’s shout that Yoni had been hit just before he charged into the room. In an instant, he spotted the terrorist’s hand and shot him through the open door as he ran, at a range of about five yards. He saw that the terrorist had been hit and finished off, and he ran into the building without pausing.

Just as he had practiced, Amir turned right as soon as hecrossed the threshold. Only then did he see that he was the only member of the Israeli force in the hall. But Amnon came in right behind him. Instead ol turning right himself, as had been planned, he decided on the spot to go left perhaps he realized that there was no one covering the entire left side of the hall, since no one had come through the first door. Amnon saw two terrorists to the left, a man and a woman, both prone or crouched on the floor. They had just come into the hall from the outside and had already had time to train their guns on Amir, who had run a short way into the room and had passed by without noticing them. But before they had time to pull the triggers, Amnon shot them both. He ran towards them, kicking the AK-47S away from the bodies. “Amnon, don’t advance!” Amir shouted, thinking he intended to move further into the hall.

After Amnon, Muki and Amos and another soldier from Muki’s team came in, all through the second door. Muki had run past the first entrance,54 to which he had been assigned, and Amos, who had been added to Muki’s team at the last minute and had been told on board the Hercules to stick to him no matter what, had simply followed his commander. After Muki entered the room, he shot at one of the terrorists that Amnon had already hit. The men now stood, weapons in hand, scouring the room for any movement. Suddenly, from the back of the room on the left, another gunman leapt up. Amos Goren opened fire and hit him in the chest, the bullets passing right through the shell of the AK-47 he was holding in his hands. 55

All four of the terrorists who had been in the hall with llie hostages, and had posed an immediate danger to them, had been eliminated. At that moment — seconds after Amir had killed the first terrorist, less than a minute after the force had encountered the Ugandan sentries, and about three minutes after it had rolled off the Hercules — the operation had essentially achieved success. It was a moment that Yoni, who had been hit only seconds before, never saw.

Meanwhile, men from the teams of Amnon and Muki, as well as from that of Amos Ben-Avraham, continued to pour in through the same door. Like those before them, they stayed close to the Ironl ol the hall at first.

Amir pressed the bullhorn to his lips and said in English and Hebrew: “Everyone down on the ground!” Had il not been for the bullhorn, his voice certainly would not have been heard, as he was so excited that he was barely able to gel a sound out of his mouth. Most of the people remained prone on the floor, probably more because of shock al what was happening around them than because of Amn’s instructions, but several of them did pump to their feel. Amnon and Amos Goren trained their rifles on a figure that rose in the far corner of the room, near the stairs. Even as they were squeezing their triggers, they realized that it was the figure of a little girl. They quickly jerked their guns upward. The bullets hit the wall above the girls head. It’s doubtful whether the small hostage understood that she had narrowly escaped death. A moment later an older man jumped up; the soldiers, realizing he was not a terrorist, shouted to one another not to fire at him.

But some were not so fortunate and were hit during the shooting. Three hostages lost their lives — two succumbing later to wounds sustained from Israeli fire; the third, Ida Borokovitch, killed on the spot, perhaps from the fire of one of the Arab gunmen.

IDF assessments before the operation had included the possibility of dozens of dead even in a “successful” operation. In fact, the swiftly executed assault caught the terrorists by surprise, and they had no chance to massacre the hostages. And conditions in the hall when the Unit’s men arrived were nearly ideal: It was well lit, all of the hostages were in one room, and in the first instant of the attack they were all still lying on the floor where they had been resting or sleeping — caught, like their captors, completely by surprise. So it was possible to hit the terrorists with lightning speed almost without endangering the hostages themselves, most of whom did not yet understand what was happening. Some had just woken up, and many were too stunned to even make a sound. Seconds earlier, when they had heard sounds of gunfire outside growing nearer, most had thought that their end had come and the massacre was about to begin. One hostage, Sarah Davidson, had thrown herself over her young son to shield him from the bullets, as the thought had flashed through her mind that it would not take long and death would come quickly.

Only one small boy reacted uninhibitedly to the Unit’s actions in the hall. When he saw the shooting, he clapped his hands and shouted with glee: “Wow, great! Great!”

Orders in Hebrew filled the hall; one of the soldiers announced, “We’ve come to take you home,” and the people began to understand that the inconceivable had indeed happened. After seemingly endless days of degradation, of repeated ultimatums and threats, of obedience to the orders of a shrill German woman whose brutality reminded one I lolocaust survivor of her block warden al Birkenau; after the “selection” of the jews, during which Ihe German man had tried lo calm them, jusl as his Nazi forebears once did, by saying that the sepaiation fromthe others was intended to improve their conditions; after days of listening to the pronouncements of the clown-tyrant of Uganda, luxuriating in the international spotlight and amusing himself at the expense of the group of hostages who had fallen under his authority; after days in which they had been exposed to the burning hatred of the Arabs, some of whom were just waiting for the chance to pull the trigger and murder the accursed Jews; after many of them already saw death as inevitable and inescapable — salvation had suddenly come, in the form of young Israelis emerging from the night.

Simultaneously, the other teams took control of the rest of the building. Giora burst into the small hall further down the building. This was where the Israeli hostages had been kept at first, and up until the moment he entered, it wasn’t clear whether they were still being held there. In a glance he saw there were no captives here and sprayed the hall and the corridor leading off to its right with bullets. In the hall there were several beds with sheets, and it seemed to him that someone was lying in one of them (the bed later proved to be empty). In front of him, on the single table in the room, were piled the hostages’ passports, and a number of suitcases stood on the floor. Giora sensed he was being fired upon from somewhere. When he had emptied his clip, he jumped back outside to replace it, since he was alone in the hall with no one to cover him. In the meantime, two soldiers from his team entered the hall and began advancing through it, firing. They reached a room that had been used as a kitchen on the far side of the hall, and when they had finished spraying it with bullets, they found two dead Ugandan soldiers inside.

Shlomo entered the small hall as well. He belonged to a different team, Amnon’s, which was assigned to the large hall, and he’d entered this room by mistake. He had known he was supposed to come through the door after the one Muki entered, and that’s what he did. But Muki had gone through the second door of the large hall rather than the first, and Shlomo ended up in the next hall. Han Blumcr, another soldier in Amnon’s team, did the same thing.

Even when lie was in the hall, Shlomo didn’t realize he was in the wrong place. “What are you doing our hall?” he asked Giora. And when he saw that the room was empty of hostages, he added: “They’ve probably moved them to the new terminal”

While he had been outside replacing his clip Giora had noticed that the team after his, Danny Arditi’s, was unable to penetrate the terminal through the entrance it had been assigned. Danny’s group was supposed to storm the VIP lounge at the far end of the building, which had served as living quarters for the terrorists. It was the team that ran last in the assault force, and as Danny had run along the front of the building, he’d seen Yoni sprawled out on the ground, with someone else stopped next to him. Danny paused for a fraction of a second, but when he heard someone nearby yell “Keep going!” he continued with his team toward their entrance. When they reached the door, they found it locked, and had difficulty breaking it open. One of Danny’s men tried throwing a grenade through a window, but it apparently hit the frame or a bar across the opening and bounced back, exploding nearby and lightly wounding one of the men in the leg. Giora, who had noticed a corridor leading from his hall to the terrorists’ quarters, shouted to Danny that he could enter his wing of the building and clean it out.

Giora and Shlomo entered the corridor, taking turns advancing while throwing grenades and firing continuously. Behind them was Tamir, Yoni’s communications man, who had been left with nothing to do after Yoni had been hit and had joined Giora’s team. While they were in one of the rooms, two people with frightened looks appeared out of the smoke. Their hands were lifted a little, as though they had not yet decided whether to raise them or not. The two moved toward Giora and passed by him. Shlomo began calling out in a mixture of English, Hebrew, and Arabic: “Stop! Who are you?” They didn’t respond, but kept moving.

“They’re terrorists!” Giora shouted to Shlomo, jumping out of his possible line of fire. “Shoot them!” Giora was unable to fire himself without endangering Shlomo, who was standing close to the two. So he yelled to Shlomo again: “Shoot them!”

Shlomo, still under the mistaken impression that he was in the vicinity of the large hall, answered: “No, they’re hostages!”

But as the pair passed him, Shlomo suddenly noticed a grenade clipped to one of their belts and realized who they were. Again, he ordered them to stop. When they kept moving away from him toward the door, he finally sprayed them with a burst of fire. As one of them fell, Shlomo saw the blue flash of a detonator. “Grenade!” he shouted, throwing himself to the floor of an alcove to one side and dragging down Tamir, who had been standing next to him. The grenade, which may have been hidden in the terrorist’s hand, exploded, but apart from Shlomo getting a tiny piece of shrapnel in his lip, none of the Israelis were wounded.

From there, they went on to clean out the area around the bathrooms, which was still full of smoke from a grenade that someone from Danny’s team had thrown in through a window. When the smoke cleared, it became evident that no one was inside. Searching back through the area they had already secured, they discovered the body of another terrorist in the corridor (Giora remembers there being two bodies). It is not entirely clear when he was killed, and by whose fire. Meanwhile, Danny’s men had succeeded in breaking in through a narrow window and mopping up part of the wing. Danny was assisted by Amos Ben-Avraham, who had been in the large hall but had seen earlier that nothing remained to be done there and had looked for another place where he could be of assistance.

While this was happening on the ground floor, Yiftah Reicher and his team were carrying out their mission on the second floor. In the initial assault, when Yiftah entered the first door of the building, he made sure that the other two members of his team were behind him; then, without waiting for his second team, under Arnon Epstein’s command, he immediately began executing his assignment. The three men quickly cleaned out the customs hall, killing several Ugandan soldiers, went out the other side of the room, and climbed the stairs to the second floor. When Yiftah reached the top ol the stairs, two Ugandans were headed toward him, but he opened fire first and killed them. At the beginning of the hallway they found the door to the platform overlooking the large hall, but it was sealed with a steel grill. Yiftah posted one of his men in the corridor to watch this door and the entrance to the second floor, while lie and Rani Cohen, his other soldier, continued mopping up. The end of the corridor opened into a large room that had once been a restaurant and now served as living quarters for the Ugandan soldiers. The room was full of blankets and sleeping bags. Only two minutes earlier, Ugandans had been sleeping there, but now no one was to be seen. They’d apparently made a lightning escape, leaping from the second floor window to the area behind the terminal.

Yiftah and Rani suddenly spotted the silhouette of a person and fired on it. When they heard glass shattering, they realized they’d fired on their own reflections in a mirror, just like in the movies. Afterwards they quickly returned to the hallway, and from there climbed several steps onto a large balcony that was actually the roof of the customs hall. They briefly searched it with their flashlights, but didn’t see anyone. Looking up, they could see the exchange of fire with the control tower.

When they returned to the hallway, Yiftah made radio contact with Arnon’s team. Arnon’s men were already outside again in the plaza, after having gone inside the building but had failed to locate the stairs to the second floor, over which they were supposed to stand guard. It’s easy to understand why they’d missed it, since the layout of this wing had been almost completely unknown to the Unit. Only at the last moment, at Sharm al-Sheikh, shortly after he had found out about it, had Yoni told Yiftah that to reach the staircase they had to cross through the customs hall to the other side of the building.

While searching for the stairwell, Arnon and his team shot several Ugandan soldiers that they ran into in a side room which Yiftah had not had time to clear. After combing the customs hall area and failing to find the staircase, they’d gone back outside. They could see that there was fire coming from the control tower, and Bukhris and another member of Arnon’s team began returning fire. They moved away from the front of the terminal so that they could shoot more effectively.

The covering force in the jeeps was also shooting at the tower. At first the men fired from where Yoni had ordered the cars to stop for the assault. Then they realized that they were in a poor position — from where they were, they couldn’t hit anyone shooting from the other side of the tower into the entrance plaza — so they drove out into the plaza. The stubborn Ugandan soldier who was posted on the the top floor of the tower continued shooting bursts throughout the entire operation, including the later stage when the hostages were being evacuated, and even afterwards. Fortunately, his fire was ineffective, in part because the counter-fire kept him from aiming properly, and no one was hit.

Now, a minute or two after the rooms had been stormed, Bukhris and Arnon spotted someone lying on his stomach further down the front of the building. They realized it was a member of the Unit who had been hit, and shouted “Someone’s wounded here!” as they ran toward him. Arnon turned over the wounded soldier, and then, in the light of the plaza, they saw that it was Yoni. “Doctor!” they shouted. David, who had positioned himself as planned next to the main entrance to the large hall, turned his head in the direction of the shout. He saw the wounded man sprawled on the ground a few yards away and came immediately. David’s rule was never to leave a wounded man where he had fallen, and he dragged Yoni, who was unconscious, closer to the building, behind a low wall. The new location, too, like the rest of the entrance plaza, was still exposed to fire from the control tower.

David heard Muki trying to raise Yoni on the radio. Right after the terrorists had been eliminated, someone had reported to Muki that Yoni had been hit, but Muki relates that he thought he heard Yoni himself calling him over the radio a few seconds later. He kept trying to call him back until David informed him on the radio that Yoni had been hit, and that he was treating him.

Yoni was very pale, and David noted other signs indicating massive blood loss. It was clear that Yoni was seriously wounded. He saw no blood on his clothing, other than on his right arm, where he had been hit in the elbow, and deduced that the hemorrhage was primarily internal. The doctor cut off Yoni’s ammunition bell and shirt with a knife, with Arnon helping him. At first he found only the exit wound left by the bullet on his back, near his thoracic spine. In spite of the good lighting in the plaza, he had a very hard time finding the entry wound; finally, he discovered a small slit under llie collar bone, on the right side of Yoni’s chest. The bleeding, then, was in fact internal, and nothing could be done to stop it. David realized that Yoni’s condition was almost hopeless.

Muki informed the entire force over the radio that Yoni had been hit and added that he was assuming command. Earlier, while the soldiers were still combing the large hall for more terrorists, one of the hostages, who had recovered from his initial shock, had come over to Mnki. The smell of gunpowder and the sharp odor of blood from the dead and wounded filled the room. “You’ve gotten all the ones that were here in the hall,” he said. “There are just a few more in the next wing.”

Those few more were the ones that Giora’s team, accidentally joined by Shlomo and Ilan, had already wiped out. After they’d finished securing what had been the terrorists’ living quarters, Shlomo had helped care for the wounded man from Danny’s team and Ilan had gone over to the large hall, to which he had been originally assigned. When Amir saw his friend coming through the door, he was overcome with joy. Not having seen Shlomo and Ilan, the other two members of his team, in the large hall, he had grown increasingly worried that they’d been hit on the way to the building in the first moments of the assault. Amir had already pictured the worst: that they were gone, just like the man from their squad who’d died in the Savoy Hotel rescue operation. Still, when Ilan appeared, Amir didn’t allow himself a display of joy. Instead, he picked up the gun of the terrorist he’d killed, and as gunshots from Yiftah’s team echoed from the second floor, he said with a big smile: “Look at this great new AK-47 I got myself.”

Coming downstairs after securing the second floor, Yiftah ran into more Ugandan soldiers, and shot them. Outside again, he joined Arnon, who headed the second team under his command. Along with several of his men, Yiftah now began cleaning out the long corridor that ran between the customs hall and the large hall and opened onto the northern entrance plaza. All that had been known in advance about this corridor, which actually led to the inner area of the terminal complex, was the little that Halivni had told Yoni at Lod.

Bukhris remained crouched next to the building, ready to fire again if need be at the control tower, which was quiet for the moment. Suddenly he felt a tap on his back and heard a few mumbled words he did not understand. He turned his head and saw the barrel of a rifle only inches from his face. At first, confused by the mottled uniform, he thought the man holding the gun was from his own force. But when he saw black skin, he shouted: “Watch it, Arnon! There’s somebody here!” The Ugandan leaning over Bukhris apparently still hadn’t fully grasped what was going on around him. Perhaps he had gone over to Bukhris because he was confused himself by the uniforms and by Bukhris’ swarthy skin, the darkest in the Israeli contingent. Arnon heard Bukhris shout, turned, saw the Ugandan with his rifle pointed at Bukhris’ head, and shot him.

With that, the contingent of the Unit that had landed in Hercules One had finished securing the old terminal and the area around it. The immediate threat to the hostages and the troops had been eliminated, except for the potential hazard still posed by the control tower. The Unit’s second task, assigned to its contingent in the four armored vehicles, was to provide peripheral defenses around the terminal. That force, under Shaul Mofaz’s command, landed in the second and third planes, and arrived several minutes after the shooting began, as the assault group was mopping up in the building. Along with it, Shomron also arrived in his command jeep.

When the second plane touched down six minutes after the first, the runway lights were still lit. Mofaz saw them from the flight deck as the plane descended, and could also identify Yoni’s vehicles moving toward the old terminal and see the start of the shooting near the building. Biran was on the same plane, sitting in Shomron’s jeep, and as the plane was making its descent, he was also looking out a window. “We’re close to landing,” Biran recounts. “The strip is nicely lit. I can see the airport over the right wing, and by the lights and other things, I can locate all the landmarks I’ve planned to look for beforehand. I know, that by the time we land, the force is supposed to be at the objective, and that if I see shooting there while we’re coming in, it’s a sign that the mission has been accomplished. If our forces are there, I’m not worried — somebody’s dealing with the problem. It’s right before we touch down, and sure enough, I see out the window that bullets are flying in the old terminal area, and I know this operation’s already wrapped up. That is, the guts of the operation have already been carried out before we even got there.”

Dan Shomron, along with Lt.-Col. Haim Oren and three other officers from his forward command group, had arrived with the Inst plane, and until the second Hercules landed with their jeep, they waited near the new terminal. They had gotten off the first plane close to where the Unit’s Mercedes and two jeeps had been put down. This was also where the main force of paratroops had deplaned to head for the new terminal on foot. The five officers remained alone in the open, near the access strip connecting the main runway to the diagonal one. During those minutes, as they awaited the arrival of theeir jeep and the first two APCs, the scene seemed surreal — senior Israeli officers standing next to each other in the darkness, in the middle of an airport in Africa, while an operation unfolded to which they were able to contribute virtually nothing. “Dan and I stood on I the edge of the runway, with no one around you had your UZI, nothing else, ”says Haim. “I said: ’Dan, what are we doing here? The other planes haven’t arrived, the Unit’s already cleared out, and we’re standing here at the end of the runway…” The sound of the Unit’s run-in with the Ugandan sentries could now be heard in the distance, and Haim suggested to Shomron: “Let’s move up landing the other planes.” But Hercules Two was already about to touch down.

After the plane landed, Nati taxied it towards the set deplaning point further down the runway. From inside the hold, Biran could see an airport pickup truck driving on the left. It had left the airport’s fire station and begun driving alongside the plane, on a service road parallel to the runway, with the light on its roof flashing. When the plane reached the turn onto the connecting strip where the forces were to deplane, the lights on the Ugandan vehicle suddenly went out. The next moment, perhaps as a result of a message from the vehicle to the control tower, all of the lighting in the area went out in three quick stages — the landing lights on the principal runways, the lights along the access road to the new terminal, and the lights in the parking area for planes — as though someone had flipped three switches. The lights went out just as the third Hercules was making its final approach and preparing to put down. For the pilot, before whose eyes the runway lights abruptly vanished, it was as if the ground had disappeared from under his feet. He skipped about half a mile forward in the air, toward the two short rows of faint lights that had been positioned earlier by the paratroops. Using these, he was able to land safely, albeit with a resounding bang.

Meanwhile, Nati brought Hercules Two to a stop on the connecting strip where Yoni and his men had put down earlier. Shomron’s jeep and the two APCs quickly rolled off the plane. Biran hurriedly assembled the antenna for the jeep’s radio, and Lt.-Col. Moshe Shapira from the Infantry and Paratroops Command, who was serving as driver, picked up Shomron and the other four officers where they were waiting nearby.

The command jeep joined Shaul’s two APCs and headed for the old terminal area. Not far behind was the second pair of APCs, under Udi’s command, which had landed in the third plane. Shanl moved as fast as possible, having seen from the air that shooting had broken out even before the assault force had reached the terminal and fearing that the operation had run into trouble. When he reached the plaza in front of the old terminal, he saw the hijacked airliner standing there. The presence of the plane here surprised the Unit, since, according to the latest intelligence reports, it was positioned at the end of the diagonal runway. In fact, the gunmen had ordered Capt. Baccos to move it earlier that day, possibly in anticipation of the press conference they planned for the next morning to celebrate Israeli capitulation to their demands. Shaul positioned his APC next to the Air France plane, tried to make radio contact with Yoni, and was told Yoni had been wounded. Inside the terminal, the assault force had almost finished mopping up.56 “There were still some shots here and there,” says Biran, who arrived at the same time in Shomron’s jeep, which parked under the control tower.

Shaul saw some Ugandans running past but didn’t bother shooting, since the plan said his force should not fire at soldiers trying to escape from the area around the building. For the moment there was no fire coming from the tower; soon after, when the shooting from the tower erupted again, Muki ordered Shaul to keep the soldier up in the tower pinned down. Shaul deployed in front of the tower, lit it up with a floodlight on the APC, and poured machine gun and RPG fire on it.

“We fired everything we had,” says Danny Dagan. “Even though I was the driver, I grabbed my AK-47 and shot every chance I got, because I felt like I had to do something. I’d get an order: ‘Danny, forward!’ or ‘Back up!’ and I’d put my gun down and drive. And in between, I was shooting the whole time.” Shauls fire was directed mainly by Alik, who’d stayed at the position he was meant to take as part of Yoni’s command team, in front of the terminal.

The second APC of Shaul’s pair passed close to the terminal. Omcr, the commander, tried calling Yoni on the radio to see if he needed help; when he got no reply, he continued according to plan toward the Ugandan army base and the Migs.

When the other two APCs, which were responsible for the defenses north of the building, reached the terminal area, they turned left into a compound that had belonged to Shell Oil. From there, they were supposed to find their way into the open stretch on the building’s north, which had once been the entrance area for people arriving at the terminal from Entebbe on the old road. When the men in the APCs found a fence blocking their way, they doubled back toward the control tower to look for another way through. They coilld see the Mercedes in front of them, its doors thrown open and its engine running. They turned left again, and after a few attempts, managed to find their way onto the north side. In the process they fired on some Ugandan soldiers who appeared to them to constitute a threat. They also fired on the generator that supplied electricity to the terminal, knocking out most of the lights in the terminal itself and the area around it. At last they deployed in front of the gate where the road from Entebbe entered the terminal area. As planned, they began calling loudly to anyone who might be in the vicinity to come to them, in case some of the hostages had fled there in panic during the battle. From there they spotted Yiftah and a few of his men, who were combing the area, and the two groups shouted to each other to avoid friendly fire. After that Yiftah cut back through the building to its south side, where the freed hostages and the rest of the assault force were located.

In the meantime, Muki went out to check on Yoni’s situation, then returned to the large hall to begin organizing the evacuation of the hostages. Alik asked the doctor about Yoni’s condition, and David replied grimly that it looked very bad. Earlier, when David had just begun treating Yoni, Alik had warned him: “If you don’t take care of him right, you’ll have to settle the score with me.” Alik had no idea how David, who was new to the Unit, would perform under fire, and thought that saying this might increase Yoni’s chances of getting proper care. Alik now entered the large hall and offered to relieve Muki there, in order to free him to take charge of the rest of the operation. Instead, Muki asked that Alik go to the fourth Hercules plane, which had landed by now, and which was to carry the hostages home. He wanted the plane moved closer to the terminal, perhaps having been told by radio that it had parked further away than planned.

Alik took Ilan with him, and the two began walking toward the diagonal runway. For a moment fire rained down on them from the control tower, and they pressed themselves against the wall of the building. A few steps further along, next to the tower, they ran into Shomron and, in response to his question, explained where they were going. Then they walked away from the terminal along the access road, only twenty minutes after they’d raced down it in the opposite direction after meeting the Ugandan sentries. They asked over the radio that the Golani contingent guarding the plane be told they were coming so they wouldn’t be fired on by accident. The two men walked carefully, guns at ready, on guard in case a Ugandan soldier leapt out at them from the high grass. On the way, Alik told his partner that Yoni had been wounded in the chest.

As they passed the point where they’d clashed with the sentries, they saw the body of one of the Ugandans sprawled on the asphalt. After a short walk, they reached the plane and the Golani troops spread out around it. The job of the sixteen Golani officers and men was to serve as a reserve force and to help evacuate the hostages. Alik and Ilan told the pilot to pull closer to the terminal, and headed back to the building.

By the time they got back, Yoni had been evacuated. Before he was moved, Dr. David Hasin had dressed the wounds on his chest with vaseline gauze and bandages, mostly to mark them for the doctors who would treat him on the plane. Without the help of the medic whom Yoni had taken off the mission roster at Lod, there was little more David could do, and he preferred in any case to move Yoni quickly to the plane, where there would at least be some chance, however slight, of saving him.

The blood continued to flow from his veins, and with it Yoni’s life was ebbing away. Yet a last spark remained. When David and Arnon were loading him onto the stretcher, “he regained semi-consciousness,” David recalls. “Apparently his soldier’s reflexes were stirred. There was tremendous shooting at the tower, which made a lot of noise, and he tried to get up.’”57

Shaul walked over from his nearby APC to the entrance plaza to help organize the evacuation and saw Yoni being treated. Danny Dagan, who had asked him to take the first opportunity to check on Yoni’s condition, got back a faulty report third-hand via another soldier that Yoni was “moderately” wounded.

David asked Shaul to call over one of the jeeps from the covering-fire team to evacuate Yoni. Hostages had already begun to gather outside, and some of them jumped into the jeep to be taken to the plane. After a brief exchange of words, the hostages got out and Yoni was lifted up on the stretcher and put in their place. Rami, commander of the covering force, drove the jeep to the plane. David couldn’t go with Yoni himself since he’d begun treating other wounded The drive was very short. On the way Rami heard Yoni mumble something he couldn’t make out.