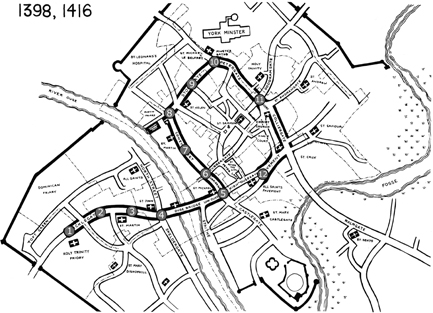

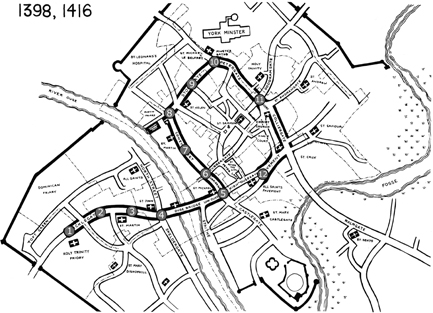

Map of pageant route showing parish boundaries.

© Meg Twycross

Anna J. Mill’s valuable article on ‘The Stations of the York Corpus Christi Play’ uses only those lists which state more or less exactly where these stations were. However, she observes that ‘others … may, with caution, be derived from the names of those who pay rent, if the location of their houses is known and is on the route indicated’.1 This sounds daunting: it is just not possible, even from the comparatively full York records, to find out exactly where two hundred and more named people lived over a time span of nearly two centuries. But one can, with caution, proceed a little further than she did. At the end of her article she provides a chart of station sites, but she makes no attempt to correlate it horizontally and has no particular interest in the names of lessees if no location is provided for them. But even lists that consist solely of names can be made to yield information when they are seen as part of a larger pattern. At the end of this article I provide a chart that not only gives the names of all station lessees in all the surviving lists, but also attempts to site them along the pageant route in what I calculate to be their correct places. Much of the pattern is provided purely from the internal evidence of the lists themselves.

As one reads through the lists, certain names become familiar: names like John Lister, Matthew Hartley, Thomas Scauceby, William Caton, and Alan Staveley. They not only appear more than once, they turn up at roughly the same place in the lists each time. Earlier attempts have tended to assume, rather unthinkingly, that Station 8, for example, will always be at the same place, but it seems much more sensible to assume that if the same person turns up for several years running at, say, Stations 10, 8, 11, and 9, that the person and the place are constants and that the numbering of the station is a variable. One can check this for stations whose places are known: between 1538 and 1572 the Minster Gates station is variously number 8, 12, 7, 11, and 9. Now the station-holder ‘at the Mynster yaitis’ in 1538, John Lister, is just finishing a run of eighteen years, for nine of which (1520–8) we have consecutive records, with varying station numbers. His neighbour ‘in Stayngayt’, Matthew Hartley, seems to have kept the same station, with one short break, for twenty-nine years (1523–51). Not many others show such remarkable runs (partly because there are breaks in the evidence, as one can see from the dates of the surviving lists), but there is an impressive amount of short- and middle-term continuity which, of course, suggests that hiring stations was a profitable affair! Then one finds the groups of associates: for example, from 1501 to 1527, a group of people (John Caldbek, Richard Ashby, John Blakey, John Myres, George Churchman, and John Cowper) take turns to pay for Station 2, never all at once, but singly, or in pairs, or even threes, with enough permutations for it to be obvious that they are neighbours, if not actually a syndicate.

Chronological same-person runs like these provide us with the horizontals for our table. The verticals are provided by the pageant route itself. The actual route remained the same for the whole period; only the stopping-places varied in number and location. Along this route, the same sequences of names will turn up from year to year, though not always in successive years: eg, Hartley, Lister, Wylde, and Nicholson (1526–8); Halliday/Hudson, Scauceby/Kilburn, and Mrs Toiler (1468, 1475). If one can pin down a location every now and then, either from information in the lists themselves or from external evidence, then the other names in the sequence can be spaced out along the intervening stretch of street: we are, after all, dealing with a real city, not a theoretical piece of elastic. The result, though some of the placings can only be relative (at what number in Petergate did Alderman Gillour reside?), is more complete than could at first be imagined possible.

One can assume that, on the whole, these stations are outside the dwelling houses of the people named on the lists. The 1416 ordinance lays down that the play shall be played ‘ante ostia et tenementa illorum vberius et melius camere soluere et plus pro commodo tocius communitatis facere voluerint pro ludo ipso ibidem habendo’:2 nearly a century and a half later, the 1554 ordinance warns that ‘suche as woll haue pageantz played before ther doores shall come in and aggree for theym before Trynytie Sonday next’.3 The formula in the lists is ‘ante ostia tenementi sui in Staynegate’ (1454), ‘ante ostia sua ad porta[m] Sancte Trinitatis’ (1468), ‘at my lady Wyldes’ (1538), ‘ageynst Heryson doore’ (1551), and ‘at William Gilmyn hows’ (1572). Occasionally the indication is made that a lessee does not own the house he lives in, but merely rents it: ‘tenemento in tenura sua’ (1454, Station 1). The word tenementum means simply a ‘building’ as distinct from a messuagium, which can include grounds: in 1454 the church of St John Ouse Bridge is described as a tenementum.

The first two lists (1398 and 1416) are anomalous in that they refer to some named houses as belonging to people who are already dead. John of Gyseburn, mercer and lord mayor, at Station 3, died in 1390, well before the date of even the first list. In the 1416 list, two more, Adam del Brigg (died 1404) and Henry Wyman (died 1411), are marked out as ‘quondam’. However, the writer of the 1416 list is concerned mainly with establishing the official status of that of 1398, so he quotes it almost verbatim. Houses (or business premises: the distinction is a false one in the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries) are occasionally known by the name of their builder, but these two lists are an exception of their kind. All other lists until very late (1551, 1569, and 1572) are concerned with recording payment from individuals rather than marking out locations, and every person on whom a check can be made appears to have been alive at the time at which payment was recorded, though some narrow margins are found. John Bateman died in December 1521, and Lady Agnes Staveley is possibly paying the fee already contracted for by her husband Alan, who died in June 1522.

The one exception is this at-home rule is the occasional hiring by a religious house. The abbot of Fountains brings a party to the station at St John’s Micklegate in 1454; St Leonard’s Hospital, which is not on the route,4 hires the nearest station, the one at the Common Hall, in 1454, 1468, 1499, 1506, and 1516. The Austin Friars (1454) and the Guild of St Christopher and St George (1468) are on their own doorstep at the Common Hall Gates.5 The other major exception is the mayoral party, to which we shall return.

One is able, though very rarely, to locate a particular house exactly through wills, mortgages, and conveyances. This area is not as promising as it might seem: very few official records of property transactions exist, and both they and wills are disappointingly vague: ‘To my sonne Peter … my gret hows in Coppergate & my landes, etc. in the parish of Alhalows upon the Pament’ (Sir John Gilliot 1509),6 or even more tantalisingly, ‘my chefe place in Yorke that I dwell yn’ (William Nelson, 1524).7 A house can be located at least along a particular stretch of pageant route, however, if one knows the parish in which the owner lived or, as it appears in the wills, in which he died and was buried. Central York was graced with a large number of churches and a correspondingly large number of parishes, and a satisfactory number of these parish boundaries intersect the roads along the pageant route, as the map below shows.

I have superimposed a map of parish boundaries over the existing street plan of York by John Harvey. Thus, if we know that William Moresby (1506, Station 4) asked in 1517 to be buried before the image of St Anne in the churchyard of St Michael Spurriergate,8 the odds are that he lived in the parish and that his station must therefore be located between the east end of Ouse Bridge and the end of Spurriergate, not at the west end of Ouse Bridge. The exception, after the Cathedral, is Holy Trinity Priory, which seems to have been popular outside its strict parish boundaries. Richard Gibson, cord-wainer, who rented Station 3 in 1499, 1501, and 1508, whom one would have thought would have been well down Micklegate in St Martin’s parish, went to Mass ‘at Trenites in Mekilgate’.9 John Ellis, senior, with whom he rented the station in 1499 and 1508, was buried there. He also turns out to have owned the Three Kings Inn, which appears under its own name in the station lists of 1551 and 1554, as he leaves it to his wife Joan in his will:

meum messuagium cum pert. in Mikkilgate, vocatum Les Thre Kingges, sicut iacet ibidem inter terram W. Holbek ex parte orientali et terram quondam W. Shirwod ex parte occidentali, unde unum caput buttat super regiam viam ante et super quoddam vicum vocatum les Northstrete retro.10

This still does not tell us precisely where the Three Kings Inn was, but it does show that the inn was on the left-hand (north) side of Micklegate: ‘les Northstrete’ in the early sixteenth century also included Tanner Row.

Map of pageant route showing parish boundaries.

© Meg Twycross

Occasionally one can pick up a location from other sources, such as the House Books and the Memorandum Books for the period.11 Thomas Wells, goldsmith, who rented Station 4 in 1486, was witness to an affray, recorded in the House Books on 27 July 1496, between Richard Thornton, sheriff, and Ralph Nevill, esquire:

Thomas Welles saith wher as on Wednesday at viij of the clok at after nowne … the said Ric. Thornton and the same Thomas satt togedder on a stall to fore the dore of the said Thos, and Sir Ric. York, knyght, and the said Rauff Nevill come togedder in armez from Skeldergate, and when they come in mydds of the strete that goeth toward Ouse brigge, Sir Ric York said he wald bryng the said Rauff to his loggyng and he said he shuld not for he wold rest hym on the above said stall and then Ric. Thornton and the said Thomas bad hym good evyn and put of theyr bonets, and the said Rauffe furthwith drewe his swerd and then and ther made assaut opon the said Ric. Thornton, and witt that Sir Ric. York toke the said Rauffe by the arme and asked him what he wald doo and pulled hym bake.12

Thomas Wells lived at the junction of Skeldergate and what is now Bridge Street, opposite St John’s Church. Because the two armed men had come from Skeldergate and were in the middle of Bridge Street before the argument started, Wells seems to have lived on the same side of the main road as the church, also the left-hand side of the route.

One is, of course, haunted by the possibility that somebody, at some point, may have moved house, or at least asked to be buried somewhere other than in the church of his parish. Occasional instances exist. Robert Cliff seems to have moved from somewhere in Coney Street (1499 and 1500) to somewhere in Pavement (1506), if one is to trust the 1506 list, which is doubtful. William Nawton (1521, 1524, and 1525) seems to have crossed the Ouse. Simon Vicars (1508 and 1521) buried his first wife in St Michael Spurriergate, which fits his station, but was living in the parish of All Saints Pavement in 1524. Thomas Scauceby (1454, 1462, and 1468), who has a son William (1475), could be, on the evidence of the date of his death, the mercer who asked to be buried with his wife and children in St Michael le Belfrey, but he and his son rent a station in Micklegate. Fortunately we have the feoffment, dated 1449, of the property in Micklegate to which he moved (see below). These are, however, unusual cases: on the whole, station lessees, even those who own several houses, seem to stay in the same place and even pass on their stations to their sons.

Much of the information about the people named in the lists can be found in the invaluable three-volume manuscript catalogue of York Worthies compiled by Robert Skaife and presented by him to York City Library in the 1890s. He provides a mass of information about dates, parishes, wills, genealogies, and miscellaneous matters for anyone who is on record as having held civic office. I have also used D.M. Palliser’s List of York Aldermen and Members of the 24, 1500–1603, deposited with the York City Library Archivist. He gives names, professions, parishes, and dates. Even the civic records, however, seem on occasion to be lacking. Richard Stirlay (1521 and 1522) is described in the pageant station lists as ‘aldermanno bowyer’ and ‘bowyer and alderman’, but he does not appear in the standard reference lists as alderman.

For those leaseholders not prominent enough to be in Skaife or Palliser, one can consult the two-volume Freemen’s Register published by the Surtees Society.13 This gives annual lists, starting from 1273, of those made free in that particular year, with their trades and professions. Those who are free per patres, in their fathers’ right, are listed separately at the end of each year as X filius X. Thus, one can confirm, for example, that Tristram Lister (1542; free 1538, draper) is indeed the son of John Lister (1520–38; free 1506, tailor). The Register is, however, not completely comprehensive. Some of the fathers in the per patres lists, for example, cannot be found earlier in their own right. Those leaseholders of whom I can find no trace either in Skaife or the Register are: Ralph Babthorp, Philip Carvour, John Pannal (1454); John and Thomas Barbour (1462, 1468, and 1475); Nicholas Caton (1499); William Caton (1501, 1506, and 1508); William Catterton (1499 and 1501); John Rothley (1501); Henry (?) Gale (1516); John Bower (1520); John Cawdewell (1522 and 1524); and Archibald Foster (1526 and 1528). On the other hand, a plethora of possible John Nicholsons (1499) exists, all free about the same time, all with possible occupations. One is aware of a certain amount of subjectivity creeping into one’s choice on such an occasion. Richard Thomson (1499), for example, could be either the baker (free 1487), the fishmonger (1489), or the glazier (1492), but the fact that he rents Station 5, which is in the region of the Ouse, makes one decide on the fishmonger. Several good circular arguments can, of course, start in this way.

The instinct to go for the most important figure bearing a particular name must, if it is present, be resisted. For example, there are two Nicholas Blackburns (1454), both merchants: the first is the notable son of a notable father, both lord mayors of York; the second is much less important, but he was alive in 1453, whereas the other died in 1447 and so cannot be our man. The minor problem of aliases sometimes occurs: the son of John Bawd (1475), free in 1461 as a ‘saddiller’, is made free as Robertus Bawd alias Sadiler (1500), and John Bawd’s partner in the 1475 station, John Gylde, seems to belong to a family of saddlers who also call themselves Driffield.

I have had a problem about how much information to put on the chart. It would, of course, be possible in many cases to append an entire biography in little. To provide brief notes on each of the persons and institutions mentioned in the lists would be helpful, but space forbids this: there are over 225 names, with information ranging from ‘nothing else known’ to full biographies. The reader should realise that the chart itself is merely the tip of a social iceberg. Who was whose son-in-law, who married whose widow, who witnessed whose will, who had a troublesome brother, who used ‘unsitting words’ to my lord mayor, even who is recorded as having been in bed by 9pm on 18 May 1555, after which his servants stole the key of Monk Bar and went outside on a drunken hunt for a grid-iron: all these build up the illusion of becoming part of a whole late-medieval urban community, closely related by ties of friendship, trade, and bickering, motivated by piety and profit. Many of the names on the chart have become characters in a fifteenth-century Forsyte Saga. For the purposes of this investigation, however, the essentials are name, profession (where known), parish (where the exact site of the station is not given), date of death (where relevant: for example, where a run of leases comes abruptly to an end), and the amount paid for the lease of the station. The lists of leases themselves occasionally record the profession of the lessee, possibly to avoid confusion with others of the same name, possibly just because other records habitually do so.

The station lists themselves come from two sources: the Council Minutes; and the Chamberlains’ Books and Rolls of Account. The Minutes, from the Memorandum Book and the House Books, are concerned only with fixing locations. They provide information for the years 1398, when an excess of unofficial stations was making the completion of the performance impossible, and repeated in 1416, when the Council are concerned with collecting revenue from leasing of stations, probably, as Margaret Dorrell suggests, for the first time, as two different methods of assessing contributions are suggested, and the third-penny system is rejected in favour of the auctioning of leases;14 1551, when the number of stations was limited to ten because of risk of infection from the plague; 1569, after a lapse due to censorship; and 1572, when the Pater Noster Play was played at the Corpus Christi stations.

The Account Books and Rolls record receipts of money from persons paying for the pageants to be ‘played before their doores’. Their fullness varies. The Rolls for 1454, 1462, and 1468 record in detail both names and sites. Between 1475 and 1528 they record names only, with a very few scattered indications of place. The first and last stations are usually described: at the gates of Holy Trinity Priory, and on the Pavement. In 1538 the accounts are in English for the first time, a practice that seems to have encouraged the bookkeeper to give full descriptions of name and place thenceforward.

The quality and completeness of the accounts also vary. The most frustrating feature from the point of view of this study is the tendency of some accounts to leave gaps for potential stations which have not been let, or for which no money has as yet come in. Some of these (notably 1520 and 1522) try to fit in two stations where only one has been usual. The three worst years in this respect are 1506, 1516, and 1525. The year 1516 has no record even of receipts. In 1525 the Creed Play was played instead of the Corpus Christi Play, and the incompleteness may be due to the fact that a different system of financing was in operation: all except one of those whose payments are recorded are or have been regulars, and may have paid for their stations in advance. The other unsatisfactory lists date from 1506 and 1516, and it is interesting to note that Alexandra Johnston thinks that these may have been years for the Pater Noster Play.15 The year 1526, however, which ought also to be a Pater Noster Play year, is perfectly normal.

One cannot be totally certain about the accuracy or even the order of all the stations in the lists. In 1501, both Stations 1 and 11 are said to be leased to William Catterton, whereas Station 11 clearly belongs to William Caton, who rents it by indenture for 5s a year between 1499 and 1508. In 1528 we have two lists, one in the Chamberlain’s Roll 6:6 and one in Book CC3, p. 232. The layout of the Roll looks competent, whereas that in the Book is careless: the writer jumps straight from Station 4 to 6, fails to give the mayoress a number, calls the next two stations 7, inserts the missing 5 between 7 and 8, and ends up losing two altogether. However, he attempts to salvage the affair by adding locations to the names, so we have reason to be grateful for his carelessness. I have reversed the order of Stations 2 and 3 in the 1454 list. Thomas Scauceby is at 2 in 1462 and 1468, and the writer of 1454 actually describes him as being in secundo loco, though he is third in sequence. The writer does not give numbers to any other stations, so it looks as if he were correcting a mistake. I have not altered any of the other lists.

It goes without saying that the legibility of the lists also varies enormously. Not only does the handwriting vary in quality, the Rolls themselves have suffered badly from damp and flooding. Some portions can be read only under ultraviolet light, and that not very satisfactorily.

The chronological layout of the table is slightly misleading. To show the diachronic continuity of station leases, I have left out the barriers between the years. It should be remembered that there is only one completely continuous sequence, that from 1520 to 1528 inclusive. The gaps between the rest vary from one to fifteen years. So Thomas Scauceby (1454–68) appears only three times, but bridges fifteen years; if the Henry Watson of 1454 (free 1435) is the same man as the Henry Watson of 1486, which he appears to be, he took out his twelve-year indenture in 1478 at about the age of sixty-four, which seems optimistic even in these days, but must have been remarkable in the fifteenth century. If he is in fact two people, father and son, this fact does not show up in the Freemen’s Register.

What can one deduce from this table? I would like to list a few observations of various kinds. Many of them are susceptible of more detailed treatment.

1 Stations did not always follow the pattern laid down in the 1398 ordinance, as is often too easily assumed; indeed, this ordinance was repeated in 1416 with the specific proviso that the 1398 stations could be varied if more profit would accrue that way, or if those at the stations refused to pay for their leases:

loca ad ludendum ludum predictum mutentur nisi ipsi ante quorum loca antea ludebatur aliquod certum quid soluerint communitati pro ipso comodo suo singulari sic annuatim habendo, et quod in omnibus annis sequentibus dum ludus ille ludi contigerit ludatur ante ostia et tenementa illorum qui vberius et melius camere soluere … voluerint pro ludo ipso ibidem habendo.16

Not only does the number of stations change from year to year, from ten in 1462 to sixteen in 1542 and 1554, but the actual sites of the stations can change, and even quite popular ones, like St John Ouse Bridge, can be eclipsed for a while (1506, 1508, and 1516).17

In practice, however, certain stations remain stable because they are ‘naturals’, either because they are in front of city landmarks like the Common Hall or Minster Gates, or because they are at road junctions, where there is more audience manoeuvrability. Others spring up before the houses of important people, like those of alderman Paul Gillour (1520–2) and Robert Wylde (1523–38) in Petergate. The most difficult to locate, and this is reflected in the chart, are those sited along streets like Micklegate and Coney Street, which are fairly lengthy and have no particularly obvious stopping places. It should be remembered that the ‘boxes’ in the chart cannot always show exact points, but merely indicate stretches of road within which a station might be situated. One might best think of them as ‘spheres of influence’ for each performance. In fact, even what seems a large number of such areas along one stretch of road need not necessarily have meant awkward crowding and interference with each other. Maps tend to straighten out the curves of Coney Street, Micklegate, and even Stonegate and Petergate. Walking round the route, one is struck by the fact that very few of the stations of which we can be certain are in fact within view or earshot of each other, and what looks on the map like a very short stretch, such as the gap between the east end of Ouse Bridge (at the Staith Head) and the junction of Low Ousegate and Spurriergate, is in fact a substantial distance. There was probably less distraction from the stations on each side than one might think.

Another and perhaps necessary caveat about the chart: naturally, the more names there are to copy out, the longer the entry will be. This does not, of course, mean that the station itself was any larger.

2 The earliest records available show that station lessees paid different amounts for their stations. Given that the leasing of stations was a commercial enterprise and not a charitable concern (though we have to take the latter into account as a possibility in some cases), we can assume that the more money people were willing to pay for a station, the more popular (and profitable) it was likely to be. It is a pity that the ‘third-penny’ method of payment was rejected, as that would give us some idea of actual audience receipts at each station.

The ‘fashionable’ areas, measured by the amount of money that people were prepared to bid for them, and sometimes the number of stations clustered along those stretches of the route, change over the years. Between 1454 and 1486, the Micklegate stretch attracts by far the largest contributions; the Spurriergate end of Coney Street comes next, but after the Common Hall payment trails off badly. Around the turn of the sixteenth century (1499–1516), Micklegate is still the most popular, but the Common Hall end of Coney Street is rising up the scale, as is Stonegate. In the 1520s, the mid-Micklegate stations are still highly popular, but the station at Minster Gates, run by John Lister, is equally so, and signs suggest that Petergate is outstripping Coney Street. In the last years, payments level out (in 1554, everyone seems to have paid a flat rate of 3s 4d, unless they are on ‘Alderman’s preferential rates’), but many more stations are massed in the latter part of the route, in Petergate, Colliergate, and in front of the residence of prosperous merchants in the Pavement.

To account for fashion is very difficult: individual enterprise (quality of beer obtainable, comfort and stability of scaffolds?) may account for a great deal, as may the shift in fashionable residential areas. Wills indicate that in the second half of the sixteenth century, prosperous merchants tend to move out of the city centre to residences outside the walls, presumably because the times were more peaceful, and also because a fair amount of land had become available after the Dissolution. Such moves could also have contributed to the tailing off of the plays themselves. However, from the point of view of the day’s entertainment, it would seem as if at the beginning of our period, people were more certain of getting their money’s worth at the beginning of the route than at the end. As the sixteenth century progresses, more confidence about the later stations seems to grow, but even so, the Pavement, which one would have thought should be greatly in demand, seems mysteriously difficult to sell. Not only does it regularly take less than the other stations when it is leased, but in many years (1468, 1499, 1508, 1520, 1521, 1522, 1523, and 1525) the space for receipts is left blank, whereas in others (1524, 1527, 1528, and 1554), it is specifically said to have been unlettable: ‘nullo super Pavimentum’ (1524); ‘nullis super Pauimentum’ (1527); ‘super Pauimentum hoc anno nihil’ (1528); and back in 1486, depressingly, ‘aliquibus denarijs’. In 1538 the statement is made that this ‘place is accustomyd to go free’, but given its previous record, this seems to be making the best of a bad job. That it is a formal station for the lady mayoress, as has been suggested, cannot be so, for in many of these years the lady mayoress is elsewhere (see section 9 below). One is led to the conclusion that the Pavement was considered a bad investment because the time schedule for the playing of pageants could fall behind and, frequently, ‘lack of day’ blacked out a fair number of the pageants at the end of the sequence.

The same argument could account for the continued popularity of the Micklegate stations. As early as 1416 they were considered a case for special treatment, though why is not stated.18 An audience in Micklegate could see all the plays before the schedule had a chance to get too dislocated, while the actors were still fresh and in good voice. They would even have some of the holiday left for other pursuits. Other possible advantages – did the slope of Micklegate allow more people to see the play at any one station?; was there an overspill from the congregation for Mass at Holy Trinity Priory?; were more of the stations inns? – can be left to the imagination.

3 In trying to identify actual houses, I have been brought to an extremely interesting though necessarily tentative conclusion. Those stations which we can identify are all on the left-hand side of the route: [See essay in this volume ‘The left-hand-side theory: a retraction’: Ed.]

As mentioned before, Northstrete included Tanner Row.

lands and tenements in Mekilgate, lying in width between the tenement of John Karr, citizen and merchant, on the one side, and the tenement of the chantry founded at the altar of St John the Evangelist in the Cathedral Church of St Peter on the other, and in length from Mekilgate in front as far as Northstrete behind.20

Other identifications are made difficult by the usual problem: exactly how accurate are the writers of the lists trying to be in their descriptions? Are subtle distinctions to be drawn among the uses of ‘ad’, ‘apud’, and ‘ante’? I am afraid that if they are, I cannot see what they might be. Since everyone knew where the houses were, there was not much point in detailing the exact location. Most of the descriptions of street locations merely indicate a junction (‘ad finem de Iowbritgate’ 1454; ‘apud le guderangaytt’ 1528; ‘at Conygstrete end enenst Castelgate’ 1554) or areas (‘ad finem Conyngstrete iuxta Aulam Communem’ 1396; ‘in medio de Connyngstrete’ 1468; ‘at Sporyer gate end’ 1538). In certain places, however, the writer seems to be making an effort to define the site more clearly. Most lists describe Station 1 as being ‘ad portas Sancte Trinitatis in Mikelgate’ (1398 and 1416), ‘apud portas Sancte Trinitatis’ (1475), or ‘at Trenytie yaitis’ (1538, 1542, 1554, 1569, and 1572). If we are to take this at face value, it would mean that the first station was on the right-hand side of the road. However, some of the lists seem to suggest otherwise. In 1454 Station 1 is said to be ‘coram tenemento in tenura sua iuxta Portam Sancte Trinitatis in Mikilgate’, that is, ‘close to, beside the gate’. In 1462 Nicholas Haliday and Adam Hudson are said to have their place ‘exopposito tenementum in tenura iuxta portam Sancti Trinitatis in Mikilgate’. (In 1468 the same people are said to be ‘ante ostiam suam ad portas Sancte Trinitatis’ and in 1475 ‘apud portas Sancte Trinitatis’.) We do possess evidence of Nicholas Haliday’s accommodation: it is, as the wording suggested, rented, and it is said to extend

between tenements of the said priory on either side, and extending from the high street of Mikelgate in York before, to a garden of the priory in the tenure of Maud Belamy behind.25

That it is said to be surrounded by Priory property suggests that it is on that side of the road:26 it may be one of numbers 99–103 Micklegate, which still exist. In that case, the writer of the 1462 list is saying that the lessees have set up their scaffold opposite their houses; the 1468 and 1475 descriptions would then be mere formulae, and we should be very cautious about reading too much into other formulae.

The left-hand-side theory has interesting implications for staging. The accounts of the Mercers’ pageant wagon suggest that it had not only a backcloth, but was, after the remodelling by Drawswerd, enclosed on three sides, much like a proscenium stage.27 If audience scaffolds were on both sides of the route, to keep turning a heavy cart round so as to face them would be extremely awkward. If they are all on the same side of the road, this does not arise. The cart can, moreover, hug the right-hand kerb (or gutter, in many cases) and give the audience maximum room to dispose themselves, standing or sitting.

4 The professions of the lessees reflect the business areas of medieval York.28 The mercantile area along Skeldergate and North Street provides merchants and grocers at the St John’s station. On the east side of Ouse Bridge we tend to find fishers and mariners: Henry Watson (1454–86), Richard Thomson (1499), John Stringer (1516), Miles Robinson (1520– 1), Richard Bateman (1526–8), and John Hogeson (1538). This station, described as being ‘at ousebrygend’, seems probably to have been actually on the end of the bridge. In the fifteenth century, Spurriergate provides fletchers, armourers, and spurriers. Coney Street, with the Common Hall, appears to be the place for merchants and lawyers. Stonegate is occupied by tailors, goldsmiths, embroiderers, and vestment-makers. Petergate and the Mercery, in what is now King’s Square, has mercers, glovers, goldsmiths, haberdashers, and, not surprisingly at the junction with Girdlergate, now Church Street, girdlers. It also seems to have cookshops and bakeries, and at least two medical men: Laurence Thomlyson (1542) at Minster Gates is an apothecary, and the mysterious Dr Adrian (1508: in Petergate) appears in 1507 in a list of Minster accounts as Magister Adrian being owed £3 10s for unspecified services, but he is between two other persons who are owed similar sums ‘pro medicinis’.29 On the Pavement are the merchants’ residences.

In 1525 the bookkeeper describes four of the eight lessees as ‘Inholder’, including Lister and Hartley, who are elsewhere said to be tailors. Provided one brewed one’s own beer, one could add this profession to one’s chief occupation.

5 Many stations were hired by more than one person. Groups like Scauceby, Wright, and Kilburn (1454–75), Parot, Scalby, and Hogeson (1462–86), Calbeck and friends (1501–28), Ellis and Gibson (1499–1508), and Mason and Wilkinson (1522–42) look very much like syndicates. Sometimes only one man is named, with the rider ‘et sociis suis’ or ‘et aliis’.

Sometimes several people hire one station but pay separate amounts, which are recorded in superscript. In 1454 Ralph Babthorp pays 5s, John Swath 2s 6d, and Thomas Bynglay 2s 6d towards a total of 10s for Station 7. In 1526 Thomas Wilman pays 3d, Archibald Foster 2d, and Widow Bekwyth 4d towards a total of 9d probably at the Common Hall. People who rent a portion of the station occupied by the mayoral party, after such a party becomes normal in the sixteenth century, pay a very much reduced rate, presumably because they would have a very much smaller area to let out for seats. In 1520 Nicholas Baxter pays 10d for his share of the mayoral station, in comparison with fees of 2s 8d, 3s 4d, and 4s 8d for other stations. In 1525, Brian Lord pays 2s for his station; the next year, he shares it with the mayor and pays only 6d. In 1501, though the mayoral party is not mentioned in the lists, William Slater pays only 12d for Station 9, which appears to be at the Common Hall Gates. The same applies to St Leonard’s Hospital in 1506. It is possible that the mayor and aldermen were already occupying station room.

6 Family continuity is shown. Fathers ‘bequeath’ stations to their sons:

Thomas Scauceby, who dies in 1471, is succeeded at Station 2 by his son William; John Lister (died 1541) hands the Minster Gates to Tristram; John Ellis Senior passes on the Three Kings station to John Ellis junior, but after a gap: he died in 1511, and his son had become free only the previous year; in 1572 Gregory Peacock was away as a member of parliament, and his station was taken by his son-in-law George Aislaby; William Gascoigne (1454) is the grandson of Henry Wyman (1398, 1416). Also, husbands pass their stations on to their wives. Alan Staveley died in June 1522, and his station was taken over by his widow Agnes. Robert Wylde, who died in 1533, was succeeded by his wife Isabel.

7 Lady Agnes Staveley also inherits what appears to be the sixteenth-century ‘Alderman’s preferential rate’. Alan Staveley (1508 and 1521) and Robert Wylde (1523) pay a much reduced rate of 12d. Later on, George Gayl (1542 and 1554) and Thomas Appleyerd (1554) pay a reduced rate of 16d. All these men were lord mayor at least once in their careers, but the rate in some cases antedates the mayoralty.

8 The problem of the lord mayor and aldermen and how their hiring of a banqueting room fits in with their claiming of a station is not actually solved, but at least the nature of the problem becomes clearer. Alexandra Johnston has conveniently listed the station evidence side by side with the chamber evidence in her review of Alan Nelson’s book.30 When this list is compared with the pattern shown by the chart, the position seems to be as follows.

Up to 1516, the lists do not earmark a station specifically for the mayor’s party, though it is possible, as I suggested in section 5 above, that they were occupying one as early as 1501. However, there are records of the hiring of a room on Corpus Christi Day from as far back as 1433. From 1476 onwards, the party are said to be ‘seeing and hearing the play’ in this room. Is the room at the same place as the station, and if not, how is ‘seeing and hearing the play’ to be interpreted?

Before 1500, the room is not identified until 1478, when it is said to belong to Nicholas Bewik. He is a vintner who in 1475 hires Station 8, which appears to be at the Common Hall Gates. He dies in 1479. In 1486 the room is said to belong to Thomas Cokke, also a vintner, who may be one of the socii of William Harpham at Station 8, which could also possibly be at the Common Hall Gates.

In 1499, 1501, 1506, and 1508, the room is said to be the hospitium of the Common Hall, but the station at the Common Hall is hired by St Leonard’s Hospital (twice) and William Slater (once). In 1508 the ‘Common Hall’ space is left blank.

In 1516 the mayor’s party is not located, but could be at the Common Hall. A note at the end of the station leases, partly illegible, appears to say that the Master and Brothers of St Leonard’s are at the Common Hall. There is no reason why they should both not be there. No receipts are recorded that would tell us if the brothers paid a reduced rate, as they did in 1506. The year 1516 is the first time the mayoral party is definitely mentioned in the station lists.

From then onwards, a station is usually allocated to the mayor and his brethren, but it is by no means always at the Common Hall. In 1521, 1522, and 1528 it probably is. In 1523, 1524, 1526, and 1527 it conspicuously is not. The year 1525 has no entry, but in that year the Creed Play was played before the mayor and his brethren, who assembled at the Common Hall to hear it.31 The year 1520 is difficult. The mayor is said to hire a station at the same place as Nicholas Baxter, who pays a reduced rate of 10d. In 1508, however, Baxter shares a station with John Bateman, who in 1521 hires the station before the mayor. There are also two more potential stations between the mayor’s party and the mid-Stonegate station, but as the spaces have been left blank, we cannot tell if they were ghost stations. The odds seem to be on the mayor’s not being at the Common Hall, but the room rental says that the person from whom it is hired is Thomas Flemyng, who later is associated with the chamber at the Common Hall Gates, and who in 1524 and 1527 hires what seems to be the Common Hall station.

In the years when the mayor appears to be at the Common Hall, no problem exists. In the years when he is not, Alexandra Johnston has pointed out that there is no specific mention of whom the room belongs to, merely that Thomas Sadler gets it ready for the party, and in some years there is no mention of the hire of a room. In 1523 Mayor Thomas Drawswerd could have entertained the company in his own home: no expenses are given for that year. The other three, John Norman, Peter Jackson, and Robert Wylde, are definitely not at home: Wylde lives in Petergate, and Jackson and Norman in the parish of All Saints Pavement. However, in 1526 Jackson shares the station with Brian Lord, who lived in the parish of St Michael Spurriergate at the top end of Coney Street. It is possible that there was a convenient room available in some hostelry in this area. One would like to propose the Bull Inn, which was at one stage in the fifteenth century used as a guesthouse for official visitors and is probably the ‘tenementum communitatis’ mentioned at Station 6 in 1468.32 However, it does not appear to have been in very good repair in the early sixteenth century: in 1511, it is said to be ‘in gret decay’.33

In 1524 and 1527, when Thomas Flemyng hires the Common Hall station, the mayor’s party is two stations up the road, and Flemyng is clearly acting as an independent agent. Not until 1535 is his name regularly mentioned in connection with the chamber at Common Hall Gates and, by that time, the mayor’s party have been taking the Common Hall station for eight successive years, long enough for the accounts of 1538 to remark that it is ‘where my Lord Mayer and his bredren ar acustomyd to be’. Eleven years in succession are quite long enough to create a custom, it seems – a fact that should perhaps be remembered when we speculate about the phrase in locis antiquitus assignatis in the 1394 ordinance.

9 The way in which the lady mayoress acquired her ‘official’ station is equally fascinating. In the fifteenth century the only surviving list to mention the mayoress is that of 1475, when Lady William Lamb takes the station on the Pavement, apparently free. Unfortunately we do not know where she lived. The first sixteenth-century mayoress to be mentioned is Lady Simon Vicars in 1521. She takes a station which in 1508 had been taken by her husband; presumably she is entertaining her ‘sisters’ in her own home. The next year, Lady Agnes Gillour takes over the lease held by her husband for the two preceding years, and possibly before, and entertains her ‘sisters’. Between 21 June and the early part of August, Paul Gillour dies, and she does not take the lease again. In 1523, Lady Matilda (Maud) Drawswerd appears to be given the Common Hall station in her official capacity, possibly because her husband is entertaining his party at home. The year 1524 has no station for the mayoress, possibly because at that time Mayor John Norman was unmarried: he married his third wife, Ann Buley, in January 1525.34 In 1525 neither mayor nor mayoress is mentioned. In 1526 Lady Peter Jackson takes the final station on the Pavement, presumably in front of the house in which her son James Jackson is living in 1542. The Jacksons have not hired a station before, but the party habit seems to be established. The next year (1527), Lady Wylde takes over the entertainment in Petergate; her husband hired the same station in 1523, 1524, after his mayoralty in 1528, and probably after that. The bookkeeper makes an interesting slip of the pen: he describes the station as ‘coram Domina maioratus’, the mayor’s house, instead of ‘maiorissa’. In 1528 Lady Thomas Mason takes Station 7, the one before her husband’s at the Common Hall. He was buried in St Nicholas, Micklegate, perhaps too near to the common clerk’s station to be acceptable for the mayoress.

At some point between 1528 and 1538 some lady mayoress must have decided it was all too much for her, as in 1538 we find Lady Wylde, now a widow, again taking a station in order to entertain the current lady mayor-ess, Lady North. In the next set of accounts, 1542, James Jackson, son of Lady Peter Jackson, provides the entertainment for Lady Jane Shadlock, who also lived on the Pavement. In 1554, William Bekwyth entertains Lady North, mayoress for the second time, at his house on the Pavement.

From the lists, it would appear that the custom grew up when a few lady mayoresses who already had an interest in a station decided to hold parties at their houses, events so successful that they settled into a custom. I have not, however, looked at the lists of expenses for the ladies’ entertainment, which may suggest a different pattern. The lady mayoress’ station naturally goes free.

10 It is surprising to find that the common clerk, who from 1501 is said to be stationed at the beginning of the route by the gates of Holy Trinity Priory, also occasionally hires a later station on his own behalf. The first one is John Shirwod in 1462: he appears to hire the Common Hall Gates station. In 1524 and 1526 Miles Newton hires the station immediately before the Common Hall. They do not, however, appear to profit from reduced rates.

11 Anna J. Mill has already pointed out the startling drop in receipts between 1486 and 1499. By the 1520s, they have dropped still further, ‘reaching’, as she points out, ‘the nadir with a mere 19s 6d and 16s 8d respectively for the 1523 and 1538 performances’.35

12 Certain persons or groups of persons secure themselves against competition by taking out for their station an indenture to run for a specified number of years. We are lucky enough to possess a copy of the indenture taken out by Henry Watson, fishmonger (1454 and 1486) in 1478, when he and Thomas Diconson engage to pay the city 11s that year and for the following twelve years to have the play played ‘in alta strata de Ousegate inter tenementa modo in tenura prefatorum Henrici et Thome scilicet apud finem Pontis Vse ex parte orientali’.36 Henry Watson’s name appears in the 1486 list of leases, but Thomas Diconson is not mentioned; other names in partnerships of this kind may well not have been recorded.

Other indenture-takers mentioned in the lists are Nicholas and William Caton, probably at the Minster Gates station, for 5s (1499– 1508). John Swath (1454 and 1462), John Smyth (1468 and 1475), Miles Robynson (1520–1), and Paul Gillour (1520–1) also pay a suspiciously steady sum.

Work on the chart is, clearly, by no means complete: various problems remain to be solved (for example, the exact place of Reginald Beesley, 1524–7), and more sites and lessees remain to be identified. However, it provides a useful tool, both for comparative work on the pageant route and for the social and topographical history of late medieval York in general.

I should like to thank Mrs Rita Freedman, the York City Archivist; Mrs Mary Thallon; and my brother, Mr Ian Pattison, FSA, of the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments, for their invaluable help during my work on this article. Mr Peter Meredith of Leeds University read an earlier draft and made many helpful suggestions.

1 Anna J. Mill, ‘The Stations of the York Corpus Christi Play’, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal 37 (1951), 492–502, Appendix III.

2 York Memorandum Book A/Y, f. 188, transcribed and translated by M. Dorrell, ‘Two Studies of the York Corpus Christi Play’, Leeds Studies in English ns 6 (1972), 90–1.

3 York City Archives, MS HB XXI, f. 44; printed by Dorrell, ‘Two Studies’, 92.

4 For St Leonard’s Hospital, see Angelo Raine, Mediaeval York: A Topographical Survey Based on Original Sources (London: J. Murray, 1955), pp. 113–16.

5 For the Austin Friary, see Raine, Mediaeval York, pp. 131–33; for the Guilds of St Christopher and St George, pp. 134, 140.

6 Testamenta Eboracensia, 5, Surtees Society 79 (1884), pp. 14–15.

7 Testamenta Eboracensia, 5, Surtees Society 79 (1884), p. 199.

8 Raine, Mediaeval York, p. 157.

9 York Civic Records, Vol. 2, ed. by Angelo Raine, Yorkshire Archaeological Society Record Series, 103 (1941 for 1940), p. 136: 27 February 1498, from MS HB8, f. 33v.

10 Robert H. Skaife, ‘Civic Officials of York and Parliamentary Representatives’ (MS held by North Yorkshire County Record Office, ?1890), 1, sv Ellis.

11 York Memorandum Book, Vol. 1, ed. by M. Sellers, Surtees Society, 120 (1912 for 1911); York Memorandum Book, Vol. 2, Surtees Society, 125 (1915 for 1914); York Memorandum Book B/Y, Vol. 3, ed. by J.W. Percy, Surtees Society, 186 (1973 for 1969); York Civic Records, Vol. 1, ed. by Angelo Raine, Yorkshire Archaeological Society Record Series, 98 (1939); York Civic Records, Vol. 2; York Civic Records, Vol. 3, YASRS, 106 (1942); York Civic Records, Vol. 4, YASRS, 108 (1945 for 1943); York Civic Records, Vol. 5, YASRS, 110 (1946 for 1944); York Civic Records, Vol. 6, YASRS, 112 (1948 for 1946).

12 York Civic Records, Vol. 2, pp. 127–8, from MS HB 8, f. 6v.

13 Register of the Freemen of the City of York, Vol. 1, ed. by F. Collins, Surtees Society, 96 (1897 for 1896); Register of the Freemen of the City of York, Vol. 2, Surtees Society, 102 (1899). Other useful information is provided by R. Skaife, The Register of the Guild of Corpus Christi in the City of York, Surtees Society, 57 (1872 for 1871) and M. Sellers, York Mercers and Merchant Adventurers, 1356– 1917, Surtees Society, 129 (1918).

14 Dorrell, ‘Two Studies’, 92.

15 A. Johnston, ‘The Plays of the Religious Guilds of York: The Creed Play and the Pater Noster Play’, Speculum, 50 (1975), 55–90 (at 73–4)

16 Dorrell, ‘Two Studies’, 90–1.

17 This is the conclusion to which the pattern on the chart forces me. It is possible that Station 4 was on the other side of the Ouse, though William Moresby belongs to the parish of St Michael Spurriergate. Of the other two lessees, John White had no recorded parish, and Thomas Parker belonged to the parish of St Martin Coney Street. There were extensive building works at St John in the period after 1506 (see An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the City of York, Volume 3: South-West of the Ouse, Royal Commission on Historical Monuments (HMSO, 1972), p. 16), but even the building of the Common Hall does not appear to have impeded the station there in 1454.

18 Dorrell, ‘Two Studies’, 90–1.

19 Percy, York Memorandum Book B/Y, p. 73.

20 Percy, York Memorandum Book B/Y, pp. 139–40.

21 See note 10.

22 Testamenta Eboracensia, Vol. 4, Surtees Society, 53 (1869 for 1868), pp. 256–7, the will of John Stockdale, alderman of York, died 1507. He leaves the house to his wife Ellen, but she did not long outlive him. The house should then have gone to ‘four of the most honest inhabitants of the parish’, but we later find his daughter and son-in-law living there (Skaife, ‘Civic Officials’, sv Wylde). The house was divided into several apartments.

23 From records held by the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments, York. I am grateful to Mr Ian Pattison for this information.

24 Skaife, ‘Civic Officials’, sv Wylde.

25 Sellers, York Memorandum Book, Vol. 2, p. 218.

26 See York, Vol. 3: South-West of the Ouse, pp. lxi–lxiii.

27 Alexandra Johnston and Margaret Dorrell, ‘The Doomsday Pageant of the York Mercers, 1433’, Leeds Studies in English ns 5 (1971), 22–34 (at 31); ‘The York Mercers and their Pageant of Doomsday, 1432–1526’, Leeds Studies in English ns 6 (1972), 11–35 (at 19).

28 See Raine, Mediaeval York, passim.

29 Testamenta Eboracensia, 4, p. 298.

30 A. Johnston, review of Alan Nelson, The Medieval English Stage, in University of Toronto Quarterly, 44 (1975), 242–4.

31 Raine, York Civic Records, Vol. 3, p. 104: 28 July 1525, from MS HB X, f. 122v. Also transcribed by Johnston, ‘The Plays of Religious Guilds’, 84.

32 In 1459, the mayor and council lay down ‘ab hac die in antea nulli alienigine, venientes de partibus extraneis ad civitatem predictam, hospitentur, nec eorum aliquis hospitetur, infra eandem civitatem, suburbia, et libertatem ejusdem, nisi solummodo in hospicio maioris et communitatis, ad signum Tauri in Conyngstrete, nisi aliter licensientur per maiorem’ (Sellers, York Memorandum Book, Vol. 2, p. 203). In 1468 it is said to be ‘exopposito’ the station of Alexander Menerous and Nicholas Saunderson, and, apparently, to share in their lease.

33 Raine, York Civic Records, Vol. 3, p. 37: entry for 15 December 1511, from MS HB 9, f.61v.

34 Testamenta Eboracensia, Vol. 3, Surtees Society 45 (1865 for 1864), p. 373 for the licence. The will of John Norman, alderman of York, 13 November 1525, is in Testamenta Eboracensia, Vol. 5, pp. 213–15. His wife Anne is already dead.

35 Mill, ‘Stations’, 498.

36 Sellers, York Memorandum Book, Vol. 2, pp. 239–40, printed from A/Y Book, f. 331v; also printed, with translation, by Dorrell, ‘Two Studies’, 92–3.