Family Tree of the Tubbacs of York

© Meg Twycross

This paper is very much a work in progress, an offshoot from the investigations currently under way on the York Doomsday Project.1 One branch of this is a study of the people involved in the play, actively as guild members or passively as audience. This particular topic suggested itself when I went back to the York Freemen’s Register2 and noticed all over again how many foreigners, practising how many different trades, are enrolled there in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries: Laurentius de Dordraght, patenmaker; Godfridus van Uppestall, webster; Nicholaus de Andwerp, cordwaner; Elias de Bruges, carnifex; Arnald de Colonia, armourer, Warmebolt de Arleham, a.k.a. Warmbald van Haarlem, goldsmith … and this is only a selection from the 1370s to 1390s. This seemed to contradict the easy assumption that York was an upcountry Northern city, possibly with big ideas about itself, but basically insular and – of course – inferior to London.

We had decided as a test case to begin our biographical hunt by asking what we knew of the careers of the people named in the 1433 Mercers’ Indenture, the first recorded pageant document after the legal incorporation of the Mercers’ Guild in 1430.3 How true was it, for example, that the 1433 Pageant Masters were, as seems to have been the case later, young Freemen in their twenties, starting out in the guild, getting their first taste of corporate organisation and accounting – and, as Louise Wheatley pointed out, catering – besides doing the legwork of actually collecting the annual contributions? And we realised, of course (it is not a new discovery), that not only did their putative ages range from 52 to 30,4 but one of them was actually a German – or what we nowadays would call a German. His name was Henry Market, he must have been in his mid-40s at least, and he came from Köln (Cologne). He had taken out letters of denization, or as we would say, been naturalised, in 1430, three years earlier.

This revived the obvious questions. How many alien immigrants were there in York? Why did the ones entered in the Freemen’s Register come so particularly from the Low Countries (the modern Netherlands and Belgium) and the Rhine basin? Why did they come to England? How long did they stay? Were they fully integrated into Yorkshire urban society or did they act like ex-patriates and keep themselves to themselves? And, if you happen to be interested in theatre and pageantry and potential Anglo-Flemish connections, did they come to York in sufficient numbers and at the right time to influence the Corpus Christi Play (or indeed the Paternoster and Creed Plays)? And were they personally involved with the production of any of these plays?

Then, on the obverse, was it a two-way traffic? Did the citizens of York travel overseas in such a way and at such times as to pick up ideas about theatrical processions from the Low Countries?

In addition, since the Project is looking at material culture, and these people were traders and craftsmen, was York, and so York theatre and pageantry, influenced in a secondary way by Flemish and Flemish-style art and artefacts, imported or made in the city by alien artisans: painted cloths, carved chests, and Books of Hours?

This is not a new idea. Alexandra Johnston has sketched one scenario in her paper on ‘Traders and Playmakers’ in the proceedings of the 1991 London conference on ‘England and the Low Countries in the Late Middle Ages’.5 She stresses the number of York mercers who were actively engaged in trade or correspondence overseas, and outlines the contemporary dramatic and processional activity in York and the Low Countries.6 But I am sure she would be the first to agree that her paper is only a taster and that we need to mount a much wider search among the relevant documents, unpublished as well as published,7 and by scholars from both sides of the Channel. The present paper is merely the first chapter.

First, a semantic clarification. Late medieval terminology on the subject of those-who-are-not-us was not exactly the same as ours, which can be misleading. Those they called aliens, ‘others’, are in medieval legal Latin alienigenae ‘other-born, of different and unfamiliar stock’. In common usage this seems to imply coming from another country. Those they called foreigners (in Latin forinsecae, etymologically ‘people outside the doors’) were ‘people on the outside’, but not, as in modern English usage, exclusively from a different nation. Although in local dialects foreigners can still imply ‘incomers’, for a late medieval citizen of York, aliens came from Haarlem, or Antwerp, or Gdansk – or Edinburgh. Foreigners came from Leeds.

The native-born are called denizens, ‘insiders’, from French dans ‘in, inside’ + ein, the suffix adopted from French for-ein < Latin forinsecae, ‘outsiders’.

So who were these aliens, where did they come from, and why were they there?

It would be convenient to be able to produce statistics, but there is a problem: how can one tell which of the names in the Freemen’s Register belonged to aliens? The difficulties of recognition are exacerbated by the clerks’ habits of writing Christian names in Latin and anglicising surnames.8 However, there are more clues than one might at first expect. It is not necessary to confine oneself to people whose places of origin in Brabant or Holland (i.e. the County of Holland, not the modern Netherlands) or Alemannia are recorded. There are certain tell-tale Christian and, especially, surnames. It is a fair bet that Petrus van Rode, Tydman van Camp, Godfridus van Uppestall, Riginaldus van the Brouke (the York scribes start using van more frequently instead of de or del towards the end of the fourteenth century), Tylman Lyon, Hermannus Horn, Matheus Rumbald, and Arnaldus Lakensnyder (‘cloth-cutter’) are aliens.9 Moreover, there may well be a hidden company. If we did not know from other sources that Henry Market and Henry Wyman were Germans, would we ever have guessed? I calculate on a rough count that at least 1% to 6% of freemen admitted every year in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries were alien-born or descended, with a downwards curve in the second half of the fifteenth century.

The alien presence in York must have fluctuated with the various political and commercial pressures of a very disturbed time. Politically, an alien could very easily wake up one morning to find himself an enemy alien. Economically, patterns of demand and supply made it more or less worth their while to come there.

Politically, for example, Edward III practised positive discrimination in favour of immigrants from Flanders,10 and there appears from the Freemen’s Register to be a sharp upwards increase in the numbers of alien incomers to York in the second half of the fourteenth century. In the first half of the fifteenth century, things took a downward trend: political alliances shifted, and then in 1435 the Treaty of Arras aligned Burgundy with France instead of with England.11 In 1436 suspicion, particularly of Flemish aliens, led to a rumour in London that they were poisoning the beer, and all aliens were asked to take an oath that they were not attempting to overthrow the regime.12 In return they were issued with certificates of political cleanliness, and the names of those to whom these were granted are listed extensively in the Patent Rolls.13 These are potentially very useful documents – if you happen to be looking at the South of England and the Midlands. Unfortunately, for some strange reason, in 1437 there appear to have been only two Flemish/Dutch/German aliens recorded in England above a line drawn from Lincoln to the Dee: John Petirson, ‘berebruer’, born in ‘Leydyn’ in Holland, dwelling at Scarburgh (Scarborough), and Adrianus Vanlere (Van Lier), born in Brabant, in Newcastle upon Tyne.14 Two years later he has migrated to York, and takes out the Freedom of the city.15 This seems so essentially unlikely that I have christened it ‘The Case of the Disappearing Aliens’, especially since the alien enrolments in the York Freemen’s Register show no diminution around this period, and three years later they have mysteriously reappeared again in national records: in the alien subsidy return of 1440, 328 aliens are recorded in Yorkshire, of which 49 are identifiably ‘Duche’ (Germanic speakers).16 The alien subsidy was what it sounds like: in 1439/1440 and recurrently for the next few years, aliens resident in England were taxed at 16d for a householder and 6d for a non-householder.17 These returns are also very useful, though the difficulties of keeping up with a transient population are well illustrated from the marginalia: in the 1439/40 return for York, of 36 aliens hospitia non tenentes (non-householders), 19 are labelled ammovet and three more mortuus/a est. The householders are somewhat more stable: only 9 out of 45 have moved (and only 3 have died).18

It is of course difficult to disentangle ‘political’ from ongoing economic rivalry. However, York does not appear to have been particularly chauvinistic: it possibly could not have afforded to be in matters of trade. There were ongoing power struggles with the Hansards over the Baltic trade, and fairly general North Sea piracy, which had localised repercussions. Different guilds had different rules about the admission and role of aliens to their mysteries, but these seem to have been dictated very much by the nature of the trade concerned.19 Their main animus seems to have been against the Scots, a more immediate threat: the 1419 prohibition against aliens holding civic office or entering the Common Hall to listen to deliberations is directed at ‘nulli Scoti nec aliquii alii aliengene’.20 York facilitated the collection of the alien subsidy,21 but although in 1439/40 the anti-alien pressure group in Parliament attempted to enforce the rules on hosting,22 the first real York attempt to corral aliens in an approved lodging, the Bull in Coney Street, does not appear to be until 1459.23 Judging from the Freemen’s Register, the number of incomers to York did not decrease drastically overall in and immediately after the 1430s. The kind of people who came changed slightly, but this may be as much due to changing commercial fashions as political pressure. In the second half of the fifteenth century, however, there is a conspicuous drop in aliens taking out the freedom of the city.

Economically, as is well known, patterns of trade shifted dramatically in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. At the beginning of the fourteenth century the main commodity was raw wool, exported largely by alien merchants for conversion into cloth in the cities of Flanders and Brabant. During the century, English merchants took over this export trade. But meanwhile the English had also been learning cloth-making skills, and at the beginning of the fifteenth century were exporting as much finished cloth as raw wool; in fact, they effectively killed the industry in the Low Countries. They also, at least in York, came to dominate the import trade in general, which may be one reason for the relative dearth of alien freemen from the 1460s onwards.24

What did our York aliens do for a living? Maud Sellers’ section in the Victoria County History follows the received line that in the early period the majority were Flemish weavers and ancillary clothworkers, imported by Edward III to set up a rival to the cloth industry of Flanders and Brabant. From the Freemen’s Register she picks, among others, Nicholas de Admare de Brabant, webster (1343); John de Colonia, webster (1343); Thomas Braban de Malyns, textor (1352); Laurence Conyng de Flandre, webster (1352); George Fote de Flandre, walker (1352); Robert de Arays, taillour (1352); Gerwin Giffard de Gaunt, textor (1355); Levekyn Giffard, his brother (1352); Gerome and Piers de Durdraght, walkers (1358); Arnald de Lovayne, teinturer (1359); and Geoffrey de Lovayn, webster (1361).25 I have done a brief sorting out of alien trades from the beginning of the Freemen’s Register in 1272 to 1370, and there are a fair proportion of dyers, tondours (shearers), walkers (fullers), weavers, and tailors. But there are also a sizeable number of other traders, especially metalworkers, of which the main branches are metal polishers (furbours) who mostly come from ‘Almain’, connected with the armour industry (armourers follow), and goldsmiths. These latter were presumably attracted to York because of the ecclesiastical trade. They keep coming steadily during the second half of the fourteenth century and are about equally spread between Netherlanders and Almains, with a recurring number from ‘Colonia’. It is just a thought, but is this why the Goldsmiths were given the Play of the Three Kings?26

From time to time we see someone identifying a gap in the market. In 1416 arrives Florencius Jansen, the first alien berebrewer (beer, with hops, appears to be a speciality of Flanders and Brabant: ale, without hops, was English),27 followed up by Johannes Tydeman (1420), Jacobus Garardson (1423), and Lamkin Vantreight (1447). There was a luxury import trade in organs and clavicymbals: in 1446 arrives Willelmus Nivell, organmaker.28 There was an unbelievably large import trade in felthattes, which came in by the hundred dozen, varied seasonally by strawhattes, and fashionably by copintank hats, and greyhattes.29 In 1462 arrived Johannes Mogan, felthatmaker, to take advantage presumably of the raw material (rabbit fur) which was exported to Flanders to make the hats in the first place: he found the trade so profitable that he was still there ‘xx yere and more’ later.30

Why did so many people emigrate to England from the Southern Low Countries? My explanations are necessarily second-hand.31 There are several possibilities arising from the particular demographic and economic circumstances of the Low Countries in the period. The area was very heavily populated. It could not feed its population from its own resources; this had forced a manufacturing economy on them rather earlier than in England, whose main export in the fourteenth century and earlier was raw wool, the bulk of it of a very high quality, which was then treated and woven in the Low Countries, especially Flanders and Brabant. Famine and the plague, when they struck, struck proportionately more severely. The area was too important to be peaceful in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, as the English slogged it out with the French, the French with the Burgundians. The English currency was relatively stable in comparison with the constantly adulterated currency of the Dukes of Burgundy. These are negative aspects. More positively, a craftsman who could offer advanced manufacturing skills but was not particularly outstanding in his own country could make a much better living in a country which could not offer these skills. The fact that several of the emigrants seem to be related to each other suggests serial migration: one member of the family tests the water and then sends encouraging messages home, and others follow.

Whether the skilled craftsmen came intending to settle, or whether they meant to make their fortunes and go back home, we cannot really tell. To find out what happened, we need to do a survey of all the putative descendants of aliens in the Freemen’s Register and elsewhere, for example, through wills.32

The other group are the merchants and mercers. This immediately raises the question of the status and intentions of these aliens in the Freemen’s Register. We tend to assume that weavers and tailors, furbours, and saddlers have come to stay. Merchants are different. Alien merchants had, if they wished to trade in their own right, to take out the freedom of the city. But this did not necessarily mean that they wished to take up permanent residence. In 1371, the York A/Y Memorandum Book talks about ‘certain folks [who] come yearly to the city, and are enfranchised’.33 So did Godefridus Overscote, mercator, de Brabane (1372) or Dericus Bogholl van Wosell, mercator (1378) do more than make a flying visit? Or did Dionysius Tukbacon (1397), Petrus Uppestall, mercator (1402), or Henricus Markett, marchaunt (1411) originally intend to stay?

I promised some case histories.34 The histories of Henry Wyman and Henry Market are relatively familiar (though their wills and their family connections will repay further study). I discard with regret Wormbold van Haarlem, goldsmith, who took out letters of denization in 1403, who got through three wives, and when the relations of the second tried, as he saw, to cheat him out of a piece of property by producing a forged writ with what they claimed to be his seal hanging from it, swore that it was not his seal, it had never been his seal, and: ‘Then in the presence of the mayor and persons aforesaid, Warmebold offered to wage judicial combat against anyone who asserted the contrary, saying that anyone who did so was wrong in his head, and with great spirit he threw down his glove on to the exchequer table.’35 Let me recommend to your attention the less famous Tubbacs and their friends the van Uppstalls.

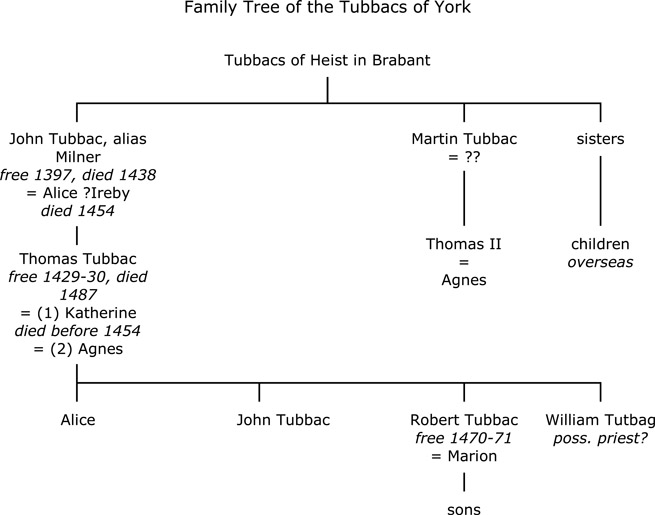

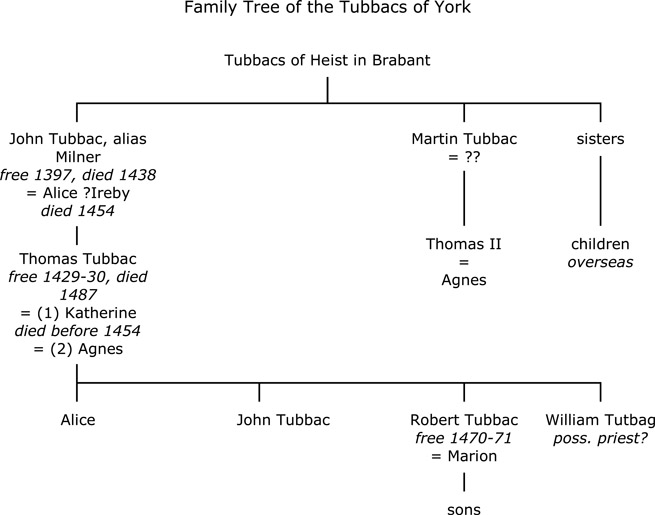

Thomas Tubbac is relatively well known to the theatre fraternity as the recipient under the will of William Revetour, theatrical priest, of ‘a certain book drawn from the Bible into English’ and 6s 8d.36 His wife Katerina (Katherine) Tutbag received an alabaster crucifix. He is the second of an immigrant mercantile dynasty – not a major dynasty, but a comfortable one – who were closely connected with the Mercers’ Company, and hence, though exactly how wholeheartedly we can only speculate, with the play of Doomsday.

The Tubbacs are difficult to disentangle partly because the local York clerks had difficulty with their name. They appear variously as Tutbag, Tutbages, Tubbac, Tubbat, and, extravagantly, Tukbacon. The last is probably the nearest to their original Flemish etymology,37 as Tuc-bake appears to mean ‘kill-bacon’, and the original Tucbak was probably a pig-sticker, as featured in the month of December in so many calendars. It is still a well-known family name, as Tobback, in modern Brabant, with representatives in both civic and national government.

There are a number of York Tubbacs in the late fourteenth century, who appear to be related to each other, though exactly how is unclear. There may have been two Tubbac families: one which died out and one which founded a dynasty. The first Tubbac in the dynasty appears himself under an alias in the Freemen’s Register, free in 1397/8, as ‘John Mylner, de Hyst in Brabancia’.38 This is almost certainly Heist-op-den-Berg, about 22 kilometres north of Leuven and 18 kilometres northeast of Mechelen. The Etymological Dictionary of the Surnames in Belgium and North France by Frans DeBrabandere39 led me to an article on ‘De familie Tobbac uit Berg’ by Paul Behets and Jules Reusens which confirmed that there were Tobbacks (with an almost equally bewildering range of spellings) in Heist in 1375, and recorded regularly there through the fifteenth century. They included a wheelwright, two tanners, and a cordwainer: two others were aldermen of Heist. Reverting to John Tubbac, though his alias Milner suggests a profession, he describes himself in his will as mercator and he seems to have lived in York as a merchant.

John allied himself with the nascent Mercers’ Guild in its social and charitable role. He appears as one of the brethren of the Hospital of the Trinity, the Blessed Virgin Mary and All Saints in Fossgate (now the Merchant Adventurers’ Hall) in its inaugural list in 1420, and is recorded as paying dues in the account rolls of the Mercers’ Company up to his death in 1438. He married Alice, possibly Ireby, possibly from a seafaring family,40 by at least 1409 (the putative date of birth of their son Thomas). From 1414 they lived and traded in two houses on Ouse Bridge, let to them by the Council at a rent of 40s per annum.41 The couple entered the Corpus Christi Guild together in 1431.42 He died in July 1438, after 40 years in the city, and in his will asks to be buried in St John’s Church, Ousebridge, ‘if he dies in York’, which implies that he might well be elsewhere, possibly trading overseas. He makes legacies to his wife Alice, his brother Martin (presumably also in York, though he is not mentioned in the Freemen’s Register), his son Thomas, and his sisters’ (plural) children ‘in partibus transmarinis’, and also to William Revetour, priest, and Nicholas Husman of Antwerp.

Alice outlived him by 16 years, long enough to see her grandchildren, Alice, John, William, and Robert. Her nephew, son of Martin, was also a Thomas, married (like almost everyone else at the time) to an Agnes. She makes no legacies to anyone overseas.

Son Thomas, the legatee under Revetour’s will, was free by patrimony (as ‘Thomas Tutbages, fil. Johannis Tutbages’) in 1429/30. He seems to have had two wives: Katherine, with whom he entered the Corpus Christi Guild in 1440/1 and who was also a legatee under Revetour’s will, and Agnes.43 He had a modest but busy civic career (chamberlain in 1454) and was much in demand as witness to deeds and inquisitions. In 1454, as one of the Guardians of St John’s Ousebridge, he acts as agent for them and the Abbot of Fountains in leasing a station outside the church for the Corpus Christi Play.44 He also turns up in the same Chamberlains’ Roll selling 8 quires of paper to the Council.45 He traded with the Low Countries and paid jetsam for the ill-fated Katherine of Hull in 1457.46 He spent his retirement (he died in 1486/7 and must have been at least 77) as Clerk to the Mercers’ Guild, which he had joined in 1438,47 where he seems to have developed a major retirement interest in witnessing wills, marching up and down Fossgate with penner and inkhorn at the ready. In his own will, he asked to be buried in St John’s next to his parents, leaving the church a chained Historica Scholastica and mentioning ‘all my books’, so he appears to have a library. He also left a violet robe trimmed with beaver, a full set of armour, and his merchants’ scales with their weights.48

Robert Tubbac, the grandson, was free by patrimony in 1470/71. He had a wife called Marion, and sons.49 He also was Chamberlain, briefly, in 1489,50 and traded overseas, mainly, from the surviving records, exporting lead and woven cloth.51 He also held office in the Mercers’ Guild and joined the Corpus Christi Guild in 1467/8.52 None of his children took out the Freedom; they may either have become gentrified or died young.53 A ‘dom. Will. Tutbag’ is mentioned in the Corpus Christi Guild lists in 1505 as one of the Keepers of the Guild for that year. He might be a son, or William, the brother of Robert, mentioned in Alice’s will. If so, the family may have died out in the male line.

We seem here to have a relatively prosperous, devout, and well-read family, with strong local attachments to church and to guild, once the guild had been created. The second and third generations enter the cursus honorum of civic office, though they do not make the top echelon: John was possibly debarred by being an alien born or possibly merely because he was finding his feet. The first generation has sufficiently close links with the homeland to leave legacies to friends there; after that there is a gradual loosening of intimacy, though we do not know anything yet about their trading companions on the other side or whether their family there survived. The son Thomas certainly was literate in English, as well apparently as in Latin.

The other elder Tubbacs appear, like John, in the 1390s. Dionysius Tukbacon, mercator, was made free in 1397, in the same list as ‘Johannes Milner de Hyst in Brabancia’. Four years earlier (1393), a Henricus Tukbacon de Malynes, wever, took out the freedom. (Again, De Brabandere records Tucbacs in Mechelen in 1311 and 1474.)54 Was this another branch of the same family? In July 1398, a Henricus Tutbak ‘de Eboraco, marcator’, writes a will in which he names Denis (Dionysius) Tutbak as his brother (‘fratri meo carnali’), forgiving him all debts and leaving him ‘all the goods of mine which are in his hands tempore recessus mei’ and £20 sterling currently in York. To ‘my other brother existenti in partibus transmarini’ he leaves £20 sterling ‘de bonis meis existencibus Eboraco et in diuersis partibus Anglie et in diuersis partibus transmarinis’.55 It sounds as if we have stumbled upon a cross-North Sea trading partnership in which Henry is a travelling partner. Despite having a base in York, he seems to have traded mainly through Great Yarmouth, where he asks to be buried by the Carmelite friars. The fact that his other brother is specifically said to live overseas seems to discount John Tutbag, alias Milner; besides this, if they were brothers, why did they both sign on at the same time under different names? However, Henry leaves 6s 8d to the church of St Mary ‘de Harelere in Brabante’, possibly Hallar on the northern outskirts of Heist op den Berg. There is a celebrated statue of the Virgin, O.L.V. van Altijddurende Bijstand (Our Lady of Perpetual Succour) in the church at Hallar, though physically she dates from the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century.56 He also names Godfridus Uppestall as one of his executors, thus introducing our second surname, also still a common one (as Van Opstall) in Brabant.

Godfrey van Upstall was made free in 1376 as a webster. He took out letters of denization on 17 June 1393 (confirmed by Henry IV on 26 May 1400),57 in which it is said that he was born in Brabant, but not where (Upstall seems to be a family name, not a place of origin), and promises not to export in his own name any wools or other merchandise except his own. He already had a flourishing import/export business: in 1383, he was importing, via Hull, swords, madder, oil, and glass on the St Mary of Veer; onionseed and soap, on the St Mary of Arnemuiden; and onions, garlic, and oil on the St Mary of Westkapelle; while exporting onions (again), calfskins, and thrums on the Godberade of Veer, Master the euphoniously-named William Halibut. In 1391 the customars of Hull record him, as an alien, exporting raw wool and calf’s hides.58 Coming in as a weaver does not seem to have inhibited a change of profession; one gets the impression that links with the other side positively encouraged trading.

Peter van Upstall (perhaps a son, perhaps a very young brother) was free in 1401 as mercator. He married Alice, sister of Richard Russell, vintner (not the more famous merchant, but the one who was Pageant Master to the Vintners, and City Chamberlain in 1426).59 The Vintners imported wine, so were merchants to that degree. He lived in the parish of St Martin, Coney Street. On 22 May 1414 he also took out letters of denization, which say that he too was born in Brabant, but do not say where. On 28 April 1416 he brought these Letters Patent to be enrolled by Roger Burton on behalf of the Mayor and the city council. They were tied up ‘cum cordulis sericis colorum rubei et viridis, suo sigillo magno in cera viridi pendente sigillatas’ [with silk cords in the colours of red and green, sealed with [the King’s] Great Seal hanging from them in green wax] records Burton: their contents are duly copied out, and we can compare them with the originals in the Patent Rolls.60 His will, proved on 14 September 1430, asks that he should be buried ‘vbicumque deus disposuerit’ [wherever God will have disposed], a common Lollard formula, but which might have added point if he were a travelling man, and he leaves his son John all the lands and tenements ‘que habeo in Harsyll in Braband’ (possibly Herselt, about 12 kilometres east-southeast as the crow flies from Heist). Alice died later the same winter as her husband, leaving an enormous amount of bedroom furniture.61 Among her many bequests to a wide circle of friends and family (which includes money to make a bier for the shrine of Corpus Christi) are two to the elder Tutbags, John and Alice, and she makes John Tutbag one of her executors. Did the Brabanders from round Heist stick together? Her son John, draper, free by patrimony in 1444 and also of St Martin Coney Street, died in 1451;62 with him the family seems to have disappeared.

Taking out letters of denization was not as common as one might expect. Until the panic of 1436, there were only one or two a year in the kingdom. They were expensive and time-consuming to solicit. You had to have impeccable references: long residence in the country, freedom of the city, usually a native-born wife and children. Henry Wyman’s letters of denization, dated 26 January 1388, state that he is a citizen of York, who has long lived there with wife and house, and paid tenths, fifteenths, and other taxes;63 Warimbald (Wormbold) Harlam’s letters, dated 18 February 1403, say that he ‘for twenty four years has dwelt at the city of York [which would put him there in 1379: he was made free in 1385], and is of the freedom of the city, as he says’.64 It clearly needed a considerable amount of thought before you took this step. Alien merchants were exempt from local and national taxes, though they paid heavier customs duties – unless they were Hansards, in which case they paid lower duties than the natives.65 It was not until 1440 that the alien subsidy taxed aliens just for being aliens. However, aliens could not officially buy or sell property (though it doesn’t seem to have prevented them from doing so) and it is possible that they were unofficially banned from civic office, though it does not seem to have debarred their sons, as we have seen above.66 Henry Wyman ‘of Almain’, the most distinguished of the immigrants, was a Hansard, possibly from Gdansk: a person of that name supplied household goods to Henry Earl of Derby during his expedition there in 1381.67 He was shipping through Hull as an alien as early as 1379, but again took out the freedom only in 1386.68 This may have been in response to a fracas in 1385, when his goods were seized in reprisal for the seizure of York merchants’ goods in Prussia, and he himself was forbidden to trade outside the realm. He obtained a royal form of release for this, but may have wanted more security.69 Two years later (26 January 1388) he took out letters of denization, and by 1406 was Mayor, a role he filled again the following year.

Henry Market, who came from Köln (he left a brother there in ordine sacerdotali, apparently with a son and daughter)70 and thus was also a Hansard, may have intended to embark on the same career. He took out letters of denization in 1430,71 and was Chamberlain in 1437 and Sheriff in 1442/3, but unfortunately he died later that year. He left one daughter, Alice, who married Thomas Beverley, one of the regular names in the Hull Customs accounts and a merchant of the Staple.72 Whether his wife’s German connections were involved in his overseas trade, I do not yet know. Their sons and grandsons kept on the Beverley family name and business. Henry also had a brother Roger with a family living in London.

These people were coming across and settling about the time that the Corpus Christi Play was taking on the form in which we know it, and the same was happening to the ommegangen of Flanders and Brabant. It is of course difficult to know exactly which were the formative years for the Corpus Christi Play. The earliest record of pageant waggons in 1376 does not necessarily imply a fully fledged pageant cycle;73 if the 1394 Memorandum Book entry saying that ‘omnes pagine corporis christi ludent in locis antiquitus assignatis & non alibi’ suggests waggon plays,74 then these pre-date anything we have from the Low Countries, even Bruges, judging from the evidence presented by Wim Husken.75 Bart Ramakers’ recent book suggests that the early evidence from Oudenaarde, recorded from 1407, shows a characteristic pattern of varied figures linked with the overall theme of the procession, but not arranged in any chronological order like the English cycle Plays, even though the characters may have spoken words.76 In Antwerp, the earliest record published is 1398. It lists a lengthy walking procession, headed by the trade guilds, with tableaux(?) of the Joys of Mary mixed with the Passion (very like the programme of a Flemish Book of Hours made for the English market); these end with ‘een poijnt van den oerdeele’ [a float of the Judgement].77 Perhaps a merchant of Brabant might have described this to a merchant of York? Or was it vice versa? Then further commerce across the narrow seas might have kept up a flow of smaller innovative ideas. The Antwerp ommegang was refurbished about the same time as the Drawswerd redoing of the Doomsday wagon, but, disappointingly, surviving illustrations show that the two waggons had very little structurally in common.78

But we must regulate our heated enthusiasm with the cold douche of evidence. Can we prove that any of our Flemings and Brabanders had any influence over what the plays looked like? Or that the people directly connected with the plays were also either aliens from the right area, or denizens who had been to the right area at the right time of year? Merely to write letters to somebody on the other side does not necessarily imply that you have been there; even to be a proven attendee at the various markets there (and I have chased some members of the Mercers’ Guild and even pageant masters through Smits’ Bronnen to the markets of Bruges and Antwerp) does not necessarily imply that you have seen their pageantry. (The Project hopes to pursue this line of investigation further in our Anglo-Belgian collaboration.) And, indeed, who was responsible for the overall look of the plays? Might the 1415 Ordo Paginarum play the same sort of role to the pageants as instructions to an illuminator does to the final illumination? Is it prescriptive or descriptive? Who designed the original Mercers’ Doomsday waggon? Was it even a mercer? Could it perhaps have been a painter like Johannes Braban (free 1365) or, if he is too early, Willelmus Smythhusen (free 1389)? Now there’s a whole new line of enquiry.

Lancaster University 1997

Family Tree of the Tubbacs of York

© Meg Twycross

Part of the research on this article was undertaken with the help of a grant made to the York Doomsday Project by the Nationaal Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek of Belgium and the British Council, for a joint research project with the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven.

I also wish to thank J.L. Bolton for his generous advice and information on the subject of economic history in general and aliens in particular, and for lending us his unpublished Oxford BLitt thesis ‘Alien Merchants in England in the Reign of Henry VI, 1422–61’. He is currently completing a book on aliens. [This appeared as The Alien Communities of London in the Fifteenth Century: The Subsidy Rolls of 1440 & 1483–84 (London: Richard III & Yorkist History Trust, 1998). (Ed.)] Very warm thanks are also due to Olga Horner for her work in the Public Record Office and advice on legal matters; to Ann Rycraft and the York Craftsmen’s and Women’s Wills Project for supplying the Project with information from their database; to Louise Wheatley for discussing the York Mercers and lending the project a copy of her unpublished MA thesis, ‘The York Mercers’ Guild 1420–1502: Origins, Organisation and Ordinances (University of York, 1993); and to my Project co-Director Pamela M. King for her advice and comments. This article is a branch of the research undertaken by the Project and has benefited, as has all published work arising from the Project, from our weekly in-house discussions.

1 [The York Doomsday Project, initially funded in 1995/1996 by a British Academy Major Research Grant, grew from a multimedia computer project on the fifteenth-century York Mystery Plays into a research project exploring all aspects of the plays and their various social, intellectual, religious, and theatrical contexts. The collaborating partners were the University of Lancaster and the British Library. (Ed.)]

2 Register of the Freemen of York from the City Records, 1: 1272–1558, ed. by Francis Collins, Surtees Society Publications (Durham: Surtees Society) XCVI (1897 for 1896). Further references to the Freemen of the City should be sought under the relevant years in this volume. N.b. that the dating is not always entirely accurate: the dates at which the names were entered changed over the years, and the earlier lists appear to have been copied from other manuscript lists.

3 Records of Early English Drama: York, ed. by Alexandra F. Johnston and Margaret Rogerson, 2 vols (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1979), I, 55–56. For the Mercers’ charter as recorded by the city officials, see York Memorandum Book, ed. by Maud Sellers, 2 vols, Surtees Society Publications (Durham: Surtees Society) CXX (1912) and CXXV (1915 for 1914), II, 135–7; The York Mercers and Merchant Adventurers, ed. by Maud Sellers, Surtees Society Publications, CXXIX (Durham: Surtees Society, 1918 for 1917), pp. 35–36.

4 William Bedale: free as mercator 1402, therefore born c. 1381 (assuming a Freedom taken out at the average age of 21), Pageant Master at 52; William Holbek, free as mercer 1424, therefore born c. 1403, Pageant Master at 30; Thomas Curteys, free as mercer 1420, therefore born c. 1399, Pageant Master at 34; Henry Market, free 1412 but alien, so born c. or before 1391, denization 1430 (at the age of 39 or older), Pageant Master at 42 at least.

5 England and the Low Countries in the Late Middle Ages, ed. by Caroline Barron and Nigel Saul (Stroud: Alan Sutton, 1995), pp. 99–114. This provides a useful summary of published work to date.

6 However, see below for the possible implications of overseas involvement in trade on dramatic activity. The mere fact of writing letters to overseas correspondents or taking decisions at home about overseas trade does not necessarily imply physical presence at or even conversations about theatrical events in the Low Countries. Johnston also says ‘the Flemish waggons undoubtedly provided a model for the northern English pageant wagons’ (p. 111); the dates involved suggest that it might possibly be the other way round.

7 Wills, as will be seen below, are a case in point. Those published in the Testamenta Eboracensia series, though useful as pointers, often turn out to be excerpted or inaccurate when compared with the originals.

8 One can see the same thing in the fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Hull Customs Accounts, where for example in 1453 one gets names like Bartholomeus White, Cristof[e]rus Constable, and Henricus Fyssher, all of whom are then qualified as Hansard: see The Customs Accounts of Hull 1453–1490, ed. by Wendy R. Childs, Yorkshire Archaeological Society Record Series, CXLIV (Leeds: Y.A.S., 1986 for 1984), pp. 4–6.

9 Petrus van Rode, coleourmaker, free 1400; Tydman van Camp, free 1408; Godfridus van Uppestall, webster, free 1376; Riginaldus van the Brouke (Vandenbroeck), shether, free 1451; Tylman Lyon, merchaunt, free 1435; Hermannus Horn, goldes-myth, free 1430; Matheus Rumbald, skynner, free 1406; Arnaldus Lakensnyder, free 1350 as Arnaldus de Lakensnither; his son Henricus is free 1380 per patres, and the name is spelt as above.

10 See The Victoria History of the Counties of England: Yorkshire, ed. by William Page, 3 vols (London: Constable, 1912; repr. London: Dawsons for University of London Institute of Historical Research, 1974) III, 438; The Statutes of the Realm I (London: 1810, repr. London: Dawson, 1963) p. 281, 11 Edw. III cap. 5 (1336/7). E. Miller, ‘Medieval York’, in A History of Yorkshire: The City of York, ed. by P.M. Tillot, Victoria County History (London: Oxford University Press for University of London Institute of Historical Research, 1961) pp. 25–116 (pp. 108–9) briefly discusses alien incomers.

11 See Caroline Barron, ‘Introduction: England and the Low Countries 1327–1477’, in England and the Low Countries in the Late Middle Ages, especially pp. 8–9, for a useful summary of these events.

12 Sylvia Thrupp, ‘A Survey of the Alien Population of England in 1440’, Speculum, 32 (1957), 262–73 (265).

13 Calendar of the Patent Rolls: Henry VI Vol. II, A.D. 1429–1436, ed. by A. Hughes and others (London: HMSO for the Public Record Office, 1907: repr. Nendeln: Kraus, 1971), pp. 537–9, 541–88; CPR: Henry VI, Vol. III, 1436–1441, ed. by A. Hughes (dec.) and A.E. Bland (London: HMSO for the Public Record Office, 1907: repr. Nendeln: Kraus, 1971), p. 37. Marie-Rose Thielmans, Bourgogne et Angleterre: Relations politiques et économiques entre les Pays-Bas Bourguignons et l’Angleterre 1435–1467 (Brussels: Presses Universitaires de Bruxelles, 1966) makes extensive use of these lists to map the distribution of aliens, their trades, and their Low Countries origins at the time, but possibly because she is largely London-centred, she does not seem to notice the strange discrepancy mentioned below.

14 CPR: Henry VI Vol. II, 1429–36, pp. 555 (Van Lier), 579 (Petirson).

15 Freemen’s Register for 1438.

16 Thrupp, ‘Alien Population’, p. 272.

17 Thrupp, ‘Alien Population’, pp. 262–4.

18 PRO E179/217/46. Many thanks to Mrs Olga Horner for researching, transcribing, and translating these documents.

19 For example, the Tapiters (additions to Ordinances 1419): any ‘alienigena natus extra terram et regnum Anglie, cuiusdam nacionis fuerit’, is to pay 53s 4d to the City as an entry fee, and 26s 8d to the guild for pageant silver (York Memorandum Book I, p. 109); the Weavers’ Ordinances (1400) demand a written testimonial from an alien’s previous master about his character and competence (York Memorandum Book I, p. 242); the Millers in 1475 decide to forbid all aliens entry to the mystery: York Memorandum Book BY [for B/Y], ed. by Joyce W. Percy, Surtees Society Publications, CLXXXVI (Durham: Surtees Society, 1973 for 1969), p. 182.

20 York Memorandum Book II, p. 86.

21 York City Chamberlains’ Account Rolls 1396–1500, ed. by R.B. Dobson, Surtees Society Publications, CXCII (Durham: Surtees Society, 1980 for 1978 and 1979), p. 67 (1449/50).

22 Making aliens stay in supervised lodgings with hosts who were responsible for overseeing their trading: The Statutes of the Realm, Vol. II (London: 1816: repr. London: Dawsons, 1963), pp. 303–5: (18 Hen. VI c. 4): this is a reinforcement of the statute of 5 Hen. IV c. 9. on hosts and surveillance, Hansards excepted (Statutes of the Realm Vol. II, pp. 145–6, mainly concerned with the preservation of bullion). It was reconfirmed in 4 Henry V c. 5 (1416: Statutes of the Realm II, p. 197). But as J.L. Bolton says, ‘the hosting legislation lasted only seven years and there were so many exceptions to it that it was pointless’ (‘Alien Merchants in England in the Reign of Henry VI, 1422–61’, BLitt Oxford 1971, p. 265).

23 York Memorandum Book II, p. 203: fol. 299r, date 27 April 1459. Compare with House Book Y B 2/4, fols. 4v, 12v, 18r (The York House Books 1461–1490, ed. by Lorraine C. Attreed, 2 vols (Stroud: Alan Sutton, 1991), I, 214, 224–5, 229–31), where the revision of articles on aliens is prompted by the Scottish invasion. There is not much detailed information about the events of the 1440s and 1450s, as the House Books do not start until 1476. It is not clear what sparked this decision in 1459.

24 See J.L. Bolton, The Medieval English Economy 1150–1500 (London: Dent, 1980), ch. 9.

25 Victoria County History, p. 439.

26 Köln Cathedral boasts the shrine of the Three Kings, containing their relics, brought there in 1164 from Milan. It is a remarkable and massive piece of goldsmiths’ work. See Arnold Wolff, The Cologne Cathedral (Köln: Vista Point, 1990), p. 9 and plates 27–32.

27 See the OED s.v. beer for quotations from Skelton’s ‘Elinor Rumming’ and Andrew Boorde’s Dietary, both attributing beer to ‘Duchemen’, and suggesting that it is detrimental to the English digestion. See also Nelly Johanna Martina Kerling, Commercial Relations of Holland and Zeeland with England from the Late 13th Century to the Close of the Middle Ages (Leiden: Brill, 1954), pp. 110–17 and 205–6. She suggests that brewing with hops was originally German. England exported ale up to c. 1375, then there was a massive importation from c.1400 to c. 1440, after which it died out from various causes. See also Laura Wright, ‘Trade between England and the Low Countries: Evidence from Historical Linguistics’, in England and the Low Countries in the Late Middle Ages, pp. 169–75, especially pp. 174–5 and notes 15–27. Of the 18 house-holding aliens in the 1440 returns for Hull, 3 are surnamed Berebrewer: PRO E179/202/112.

28 Hull Customs Accounts, pp. 59, 190, 193; York Mercers and Merchant Adventurers, p. 70, for the buying of an organ in Bergen-op-Zoom.

29 See for an example Hull Customs Accounts, pp. 46–7: the freight of the Mary of Hull and the Katherine of Veer.

30 House Books Y B 2/4 fol. 130v: dated 1 September 1484, certification that ‘John Mogan, ducheman’ is a freeman and denizen of the city: York House Books, pp. 322–3.

31 These factors were suggested to us by J.L. Bolton.

32 The information supplied to the Project by the York Craftsmen’s and Women’s Wills Project headed by Ann Rycraft has already proved invaluable.

33 ‘… pur ceo que certeins gentz veigne chascun an a la citee et sount enfranchisiez …’ York Memorandum Book I, pp. lxv, 14. Much of the trading must also have been managed by factors, as was customary on the other side of the North Sea.

34 Pioneering work on the biographies of York worthies was done by Robert Skaife, Civic Officials of York and Parliamentary Representatives (York City Library, MS, c. 1890). He does not, however, cover those who were not involved in the city’s administrative hierarchies.

35 York Memorandum Book B/Y, pp. 49–50 (1422).

36 York, Borthwick Institute, York Probate Register 2, fol. 138v; see Testamenta Eboracensia II, ed. by James Raine, Surtees Society Publications (Durham: Surtees Society, 1836), XXX, p. 117. See also Meg Twycross, ‘Books for the Unlearned’, in Drama and Religion, ed. by James Redmond, Themes in Drama, V (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), pp. 65–110.

37 See Frans DeBrabandere, ‘De familienaam Tobback’, Vlaamse Stam, 26 (1990), 955–6, and his Woordenboek van de Familienamen in Belgie & Noord Frankrijk (Brussels: Gemeentekrediet, 1993) s.v. Tobback(x), etc. I use the word ‘Flemish’ in its popular meaning of the form of Dutch spoken in the Southern Low Countries. The Tubbacs are of course Brabanders in origin.

38 He calls himself Johannes milner alias dictus Tutbag Ciuis mercator Ebor. in his will, York Probate Register 3, fol. 526v. In the B/Y Memorandum Book on 31 October 1424, he is called John Mylner alias Tutbag: see below, note 41.

39 See note 37. I was introduced to this by Edward Vanhoutte and Benny De Cupere, who kindly brought me back a copy from Belgium.

40 Her will (York Probate Register 2, fols 296v–297r) leaves money to ‘Agnes Ireby my relative’. A Willelmus de Irby, mariner, was free in 1356: he was Chamberlain in 1374. But her connections need further research.

41 York Memorandum Book B/Y, p. 63: ‘John Mylner alias Tutbag’, citizen of York, and Alice his wife: two houses on Ouse Bridge, with the two rooms above them and another room over the stallage of the said bridge called Salmonhole: rented for 20 years from Whit Sunday 1414, and an additional 8 years thereafter. Rent 40s p.a. Given at York 31 October 1424. Marked ‘Void’ in margin, but unclear why. In his will, proved in 1438, John leaves Alice ‘omnes terminos [‘leases’? ‘bonds’?] meos quos habeo in illis duobus tenementis in quibus inhabito super Pontem Vse’. In her will, dated 1454 (see note 40), Alice leaves her son Thomas all ‘bonorum meorum in Shopa existencium’.

42 The Register of the Guild of Corpus Christi in the City of York, ed. by R.H. Skaife Surtees Society Publications, LVII (Durham: Surtees Society, 1872 for 1871), p. 32: John Tudbag et Alicia uxor.

43 John Tubbac does not mention a wife of Thomas in his will, dated 1438. Thomas’ wife becomes a sister of the Mercers’ Guild and Hospital in 1440 (‘Item, recevyd of Thomas Cutbagg [sic in transcription] for his wife to be a sister, xxd.’): Sellers, York Mercers, p. 52. Had they just married? They enter the Corpus Christi Guild in 1440/1 as ‘Tho. Tutbak. Katerina uxor ejus’: Corpus Christi Guild, p. 38. Revetour leaves an alabaster crucifix to Katherine Tutbag in his will of 1446 (Testamenta Eboracensia II, p. 117). However, when Alice dies in 1454, Thomas’ wife is named as Agnes, and she is named Agnes when Thomas dies in 1487.

44 York Chamberlains’ Rolls, p. 90 (1454/5): REED: York, p. 85.

45 York Chamberlains’ Rolls, p. 99.

46 Sellers, York Mercers, p. 59.

47 Sellers, York Mercers, p. 49. His parents pay a large sum ‘in alms’ at the same time. His father dies that year.

48 York Probate Register 5, fol. 299v.

49 Information from will of Thomas his father, and Mercers’ Cartulary: see Louise Wheatley ‘The York Mercers’ Guild 1420–1502: Origins, Organisation and Ordinances’ (unpublished MA thesis, University of York, 1993), p. 296. His will does not seem to be extant.

50 The Freemen’s Register gives this as 1488, R.B. Dobson’s lists in his edition of the York Chamberlains’ Rolls as 1489 (p. 212). Robert seems however to have struggled financially. On 1 April 1489 he was released from the office of Chamberlain until he is ‘so growen in goodes that he be able to take the same office upon hym’: House Books, pp. 644–5. Earlier, in 1484, he was discharged from all office against the payment of 16d English (Housebooks, p. 329).

51 Hull Customs Accounts, pp. 179 (1473, Hilda of Hull), 211 (1489/90: Maryknyght of Hull), 214 (1489/90: Trinity of Hull), 216 (Maryknyght: 1489/90). His surname is spelt Tutbage, Tuttbag, and Tutbag.

52 Corpus Christi Guild, p. 73: Rob. Tutebag.

53 Corpus Christi Guild, p. 162.

54 Woordenboek van de Familienamen s.v. Tobback(x): 1311 Reyner Tucbake, Mechelen; 1474 Rommout Tucbacx, Mechelen.

55 York Probate Register 3, fol. 4r. There is no will recorded for Denis Tubbak.

56 Paul Welters, Beknopt Overzicht van de Kerken van Heist-op-den-Berg (Heist-opden-Berg: the author, 1992), pp. 7–10. There was a church there from 1131; it was however dedicated to the Holy Cross. At the end of the fourteenth century it was known as the Capellania de Herlaer Sancte Crucis, and the dedication does not seem to have been changed to Our Lady until 1502. The oldest part of the existing church appears to have been built in the fourteenth or fifteenth century. At some point in its history during a period of severe sickness, the church became so derelict that it was totally covered with ivy. Further research seems necessary.

The other possibility is a small but elegant chapel attached to the castle of Herlaer, about 4 kilometres north of Heist. This has always been dedicated to Our Lady; however, the present owner does not think that it was a likely candidate for bequests from a merchant and artisan, as its main worshippers would have been the family and the estate workers. Besides this, the castle was not necessarily known as Herlaer (after the family) in the late Middle Ages, merely as ten Hof.

57 CPR: Richard II Vol. V, 1391–96, ed. by G.J. Morris (London: HMSO for PRO, 1905; repr. Kraus 1971) p. 285; confirmed by Henry IV on 26 May 1400, CPR: Henry IV Vol. I, 1399–1400, ed. by R.C. Fowler (London: HMSO for PRO, 1903; repr. Kraus 1971), p. 295.

58 H. Smit, Bronnen tot de Geschiedenis van den Handel met Engeland, Schotland en Ierland, 2 vols, Rijks Geschiedkundige Publicatie, LXV (‘s-Gravenhage: Martinus Nijhoff, 1928), I, 359–60, 367 (1383/4), 422–23.

59 See his will, York Probate Register 2, fol. 633r, and her will, fol. 640v. Vintners’ petition: York Memorandum Book B/Y, p. 157.

60 York Memorandum Book II, pp. 49–50: CPR: Henry V Vol. I, 1413–1416 ed. by R.C. Fowler (London: HMSO for PRO, 1910; repr. Kraus 1971), p. 194, summary only.

61 See above note 58; and Testamenta Eboracensia II, pp. 8–9. Her will is dated 27 December 1430.

62 York Probate Register 2, fol. 255v.

63 CPR: Richard II Vol. II, 1385–1389, ed. by G.J. Morris (London: HMSO for PRO, 1900; repr. Kraus 1971), p. 463.

64 CPR: Henry IV Vol. II, 1401–1405, ed. by R.C. Fowler (London: HMSO for PRO, 1905; repr. Kraus 1971), p. 204.

65 Bolton, Medieval English Economy, p. 308; Childs, Hull Customs Accounts, p. xii.

66 Various cases recorded in the Patent Rolls suggest that any property bought by an alien was to be forfeited to the King: CPR: Henry VI Vol. IV, 1441–1446, ed. by A.E. Bland (London: HMSO for PRO, 1908; repr. Kraus 1971) pp. 20, 31, 63. The 1419 ban on entering the York Council Chamber, presumably for fear of espionage, would have disqualified them in practice.

67 Expeditions to Prussia and the Holy Land made by Henry Earl of Derby (afterwards King Henry IV) in the years 1390–1 and 1392–3, being the Accounts kept by his Treasurer during two years, ed. by Lucy Toulmin Smith, Camden Society, 2nd Series, LII (1894), p. 165: ‘per manus Henrici Wymmon’.

68 Smit, Bronnen, p. 329 (Hull 1378/9).

69 Calendar of Close Rolls Preserved in the Public Record Office: Richard II Vol. III, 1385–1389, ed. by W.H.B. Bird (London: HMSO for PRO, 1908; repr. Kraus 1972), pp. 2–3 (29.9.1385). He is described as ‘merchant of the Hanse in Almain’, but stands bail not to leave the country.

70 York Probate Register 2, fol. 69v–70r Testamenta Eboracensia II no. 78. His bequests and obits show an interesting circle of friends and colleagues, including Henry Wyman and his wife.

71 CPR: Henry VI Vol. II, 1429–1436, p. 43 (26 February 1430), by petition in Parliament: summary. These are entered in full into the A/Y Memorandum Book, fols 289v–290r (York Memorandum Book II, pp. 185–6). He is said to be born ‘infra partes Almannie’. He sought a royal writ confirming these letters in 1441 (18 October 1441) and had this recorded in the B/Y Memorandum Book, fols 114v–115r (York Memorandum Book B/Y, p. 152). These charge the Mayor etc. ‘to allow him all privileges, offices, and customs within the city’; possibly he was intending to stand for Sheriff and someone had contested the legality of this.

72 He was Mayor in 1460 and 1472. See also his will (York Probate Register 5, fol. 184r) and that of his wife (York Probate Register 5, fol. 28r). Since he is not of immediate concern here, I do not give details of his career. There is a genealogical note in Testamenta Eboracensia III, pp. 196–7.

73 REED: York, p. 3.

74 REED: York, p. 8.

75 Wim Hüsken, ‘The Bruges Ommegang’, in Formes teatrals de la tradició medieval: Actes del VII Colloqui de la Société Internationale pour l’Étude du Théâtre Médiéval, Girona, Juliol de 1992, ed. by Francesc Massip (Barcelona: Institut del Teatre, 1995), pp. 77–85. Costumed characters of the 12 Apostles and 4 Evangelists are recorded as walking in the procession of the Holy Blood in 1396; there appears to have been a mobile show of the ‘Play of the Garden of Gethsemane’ in 1397 for the next few years – possibly, as Hüsken suggests, a series of tableaux on waggons. Whether these spelen were genuine plays or tableaux is unclear.

76 B.A.M. Ramakers, Spelen en Figuren: Toneelkunst en processiecultuur in Oudenaarde tussen Middeleeuwen en Moderne Tijd (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 1996).

77 Leo de Burbure, De Antwerpsche Ommegangen in de XIVe en XVe Eeuw (Antwerp: Kockx, 1878), pp. 1–5: the Judgement float is on p. 4.

78 See my ‘The Flemish Ommegang and its Pageant Cars’, Medieval English Theatre, 2:1 (1980), 15–41 and 2:2 (1980), 80–98.