not only printing in Ukrainian and importing literature in Ukrainian into the Russian Empire but even the use of the terms “Ukraine” and “Ukrainian.” The Ukaz caused the emigration of many Ukrainian intellectuals to Galicia, where they could publish in Ukrainian.[129]

Although the Galician Ruthenians differed from the Russian Ukrainians culturally and politically in many respects, they were similar to each other in that they lived mainly in the countryside and were under-represented in the cities and industrial regions. During the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth, Ukrainians in Lviv numbered between 15 and 20 percent.[130] In Kiev, 60 percent of the inhabitants spoke Ukrainian in 1864; but by 1917, only 16 percent.[131]

One group of Galician Ruthenians, known as Russophiles, further complicated the process of creating a Ukrainian nation. The origins of this movement can be traced back to the 1830s and 1840s, although it did not expand until after 1848. The Russophiles claimed to be a separate brand of Russians, although their concept of Russia was ambiguous and varied in relation to the context, between Russia as an empire, eastern Christianity, and eastern Slavs. The Russophile movement was created by Russian political activists, and by the local Ruthenian intelligentsia who were disappointed by the pro-Polish policies of the Habsburg Empire, especially in

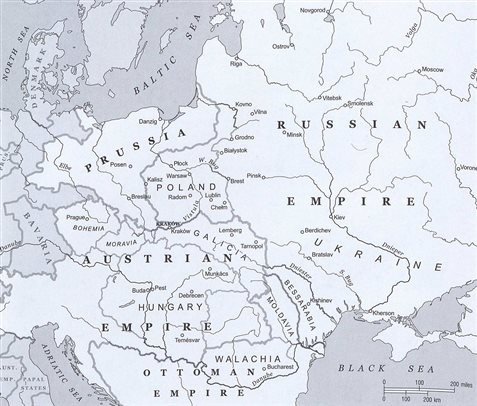

Map 2. Eastern Europe 1815. YIVO Encyclopedia, 2:2144.

the late 1860s. The Russophiles identified themselves with Russia, partly because of the Russian belief that Ukrainian culture was a peasant culture without a tradition of statehood. Identifying with Russia, they could divest themselves of their feelings of inferiority in relation to their Polish Galician fellow-citizens who, like the Russians, possessed a “high culture” and a tradition of statehood.[132]

Galician Ukrainian culture was for centuries deeply influenced by Polish culture, while eastern Ukrainian culture was strongly influenced by Russian culture. As a result of long-standing coexistence, cultural and linguistic differences between Ukrainians and Poles on the one side became blurred, as they did between Ukrainians and Russians on the other. The differences between the western and eastern Ukrainians were evident. The Galician dialect of Ukrainian differed substantially from the Ukrainian language in Russian Ukraine. Such political, social, and cultural differences made a difficult starting point for a weak national movement that sought to establish a single nation, which was planned to be culturally different from and independent of its stronger neighbors.[133]

The western part of the Ukrainian territories was dominated by Polish culture from 1340 onwards, when King Casimir III the Great annexed Red Ruthenia (Russia Rubra), with a break between 1772 and 1867, during which Austrian politicians dominated and controlled politics in Galicia. Motivated by material and political considerations, the Ukrainian boyars and nobles had already become Catholics in pre-modern times and had adopted the Polish language. The Polonization of their upper classes left Ukrainians without an aristocratic stratum and rendered them an ethnic group with a huge proportion of peasants. Polish language and culture were associated with the governing stratum, while the Ukrainian equivalents were associated with the stratum of peasants. There were many exceptions to both propositions. For example, the Greek Catholic priests might be classified as Ukrainian intelligentsia, while there were numerous Polish peasants. However, the difference between the “dominant Poles” and the “dominated Ukrainians” caused tensions between them and, as a result of a nationalist interpretation of history, caused a strong feeling of inferiority on the part of the Ukrainians.

Until 1848, Ukrainian and Polish peasants in Galicia were serfs of their Polish landlords. They were forced to work without pay from three to six days a week on their landlords’ estates. In addition they were often humiliated and mistreated by the landowners.[134] Even when serfdom was ended in 1848, the socio-economic situation of the Galician peasants did not significantly improve for many decades. In eastern Galicia, where the majority of the peasants were Ukrainians (Ruthenians) and almost all the landlords were Poles, serfdom had a significant psychological impact on the Ukrainian national movement.[135]

The Greek Catholic Church had strongly shaped the identity of Galician Ukrainians and had influenced Galician Ukrainian nationalism from its very beginnings. The Church was originally a product of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. As the direct result of the Union of Brest of 1595‒1596, the Greek Catholic Church severed relations with the Patriarch of Constantinople and accepted the superiority of the Vatican. It did not, however, change its Orthodox or Byzantine liturgical tradition. When the Russian Empire absorbed the greatest part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth between 1772 and 1795, it dissolved the Greek Catholic Church in the incorporated territories and replaced it with the Orthodox Church. The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church continued to function only in Habsburg Galicia, where it became a Ukrainian national church and an important component of Galician Ukrainian identity.[136]

Especially in the early stage of its existence, the Ukrainian national movement in Galicia was greatly influenced by the Greek Catholic Church. The secular intelligentsia in eastern Galicia who took part in the national movement emerged to a large extent from the families of Greek Catholic priests. Many fanatical Ukrainian activists in the nationalist cause, including Stepan Bandera himself, were the sons of priests. Furthermore, it was only with the help of the Greek Catholic priests present in every eastern Galician village that the activists of the Ukrainian national movement could reach the predominantly illiterate peasants. This situation changed only in the late nineteenth century, when such educational organizations as Prosvita established reading-rooms in villages. In these institutions the peasants could read newspapers and other publications that disseminated the idea of a secular Ukrainian nationalism.[137] However, even after a slight emancipation from the Greek Catholic Church, the Galician brand of Ukrainian nationalism was steeped in mysticism and had strong religious overtones. The Greek Catholic religion was an important symbolic foundation of the ideology of Ukrainian nationalism, although not the only one.

Modern Ukrainian nationalism, as manifested in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in Galicia, became increasingly hostile to Poles, Jews, and Russians. The hostility to Poles was related to the nationalist interpretation of their socio-economic circumstances, as well as the feeling that the Poles had occupied the Ukrainian territories and had deprived the Ukrainians of a nobility and an intelligentsia. The nationalist hostility to Jews was related to the fact that many Jews were merchants, and to the fact that some of them worked as agents of the Polish landowners. The Ukrainians felt that the Jews supported the Poles and exploited the Ukrainian peasants. The resentment toward Russians was related to the government by the Russian Empire of a huge part of the territories that the Ukrainian national movement claimed to be Ukrainian. While the Jews in Galicia were seen as agents of the Polish landowners, Jews in eastern Ukraine were frequently perceived to be agents of the Russian Empire. The stereotype of Jews supporting both Poles and Russians, and exploiting Ukrainians by means of trade or bureaucracy, became a significant image in the Ukrainian nationalist discourse.

Ukrainian nationalism thrived in eastern Galicia rather than in eastern Ukraine where the activities of the Ukrainian nationalists were suppressed by the Russian Empire. The political liberalism of the Habsburg Empire, as it developed after 1867, made Galician Ukrainians more nationalist, populist, and mystical than eastern Ukrainians. During the second half of the nineteenth century, the systematic policy of Russification in eastern Ukraine made the national distinction between Ukrainians and Russians increasingly meaningless. Most eastern Ukrainians understood Ukraine to be a region of Russia, and considered themselves to be a people akin to Russians.[138]

Because of the nationalist discourse that took place in eastern Galicia, the province was labeled as the Ukrainian “Piedmont.” Because of their loyalty to the Habsburg Empire, Galician Ukrainians were known as the “Tyroleans of the East.” In Russian Ukraine, on the other hand, the majority of the political and intellectual stratum assimilated into Russian culture and did not pay attention to Ukrainian nationalism. “Although I was born a Ukrainian, I am more Russian than anybody else,” claimed Viktor Kochubei (1768–1834), a statesman of the Russian Empire with Ukrainian origins.[139] Nikolai Gogol’ (1809–1852), born near Poltava in a family with Ukrainian traditions, described Cossack life in his novel Taras Bulba in a humorous, satirical, and grotesque way. His books appeared in elegant Russian, which included Ukrainian elements, and were written without national pathos. In 1844 Gogol’ wrote in a letter: “I myself do not know whether my soul is Ukrainian [khokhlatskaia] or Russian [russkaia]. I know only that on no account would I give priority to the Little Russian [malorosiianinu] before the Russian [russkim], or the Russian before the Little Russian.”[140]

The Beginnings of Ukrainian “Heroic Modernity”

Ukrainian heroic modernity found expression for the first time in the writings of the nationalist extremist Mykola Mikhnovs’kyi (1873–1924), although it derives from the thoughts of such activists as Mykhailo Hrushevs’kyi, Mykhailo Drahomanov, and Ivan Franko. The most influential of these was Hrushevs’kyi, a historian and politician. In the nineteenth century, thinkers such as Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Friedrich Engels elaborated on the popular problem of “historical” and “non-historical” nations, to which Hrushevs’kyi responded. Starting from ancient times, Hrushevs’kyi rewrote the history of the Eastern Slavs, displaying bias in favor of the Ukrainian national movement and regarding the Russian and Polish national movements with disfavor. In his voluminous History of Ukraine-Rus’, he separated Ukrainian history from Russian history, claiming that the Ukrainian people had ancient origins. He thereby “resolved” the problem of the “non-historical” Ukrainian people, making it as historical and as rich in tradition as the Polish and Russian peoples. This was one of the most significant late nineteenth-century “academic” contributions to the creation of a national Ukrainian identity.[141]

In his historical writings, Hrushevs’kyi did not insist that the Slavs or Ukrainians were a pure race or had to be viewed as a race. Nevertheless he used the term “race” in the context of anthropology. Writing about the ancient peoples living in the territory of contemporary Ukraine, he mentioned “dolichocephalic” (long-headed) and “brachycephalic” (short-headed) types of people inhabiting the Ukrainian territories in ancient times. He argued that “the Slavs of today are predominantly short-headed” but racially not uniform. The brachycephalic type “is still the dominant type among Ukrainians, but among the Poles and Russians this type vies with the mesaticephalic [medium headed], with a significant admixture of the dolichocephalic.”[142] Looking for the origins of the Ukrainian people among ancient peoples, Hrushevs’kyi concluded that the “Ukrainian tribes” originated from the Antes: “The Antes were almost certainly the ancestors of the Ukrainian tribes.”[143] While analyzing ancient and medieval descriptions of people living at that time in the Ukrainian territories, he pondered about the ideal type of a historical Ukrainian and wrote that Ukrainians were “blond-haired, ruddy-skinned, and tall” and “very dirty” people.[144]

Mikhnovs’kyi, much more radical than Hrushevs’kyi, was the pioneer of extreme Ukrainian nationalism. He lived in Russian Ukraine, mainly in Kharkiv. Because he died in 1924 he did not come into contact with the radical Ukrainian nationalists from the UVO or OUN, but his writings inspired the younger generation.[145] Mikhnovs’kyi politicized the ethnicity of Ukrainians and demanded a “Ukraine for Ukrainians” (Ukraїna dlia ukraїntsiv). He might have been inspired by Hrushevs’kyi’s historization of contemporary Ukrainians and by contemporary European discourses that combined nationalism with racism. Although Mikhnovs’kyi’s concept of ethnicity was based on language, his main aim was a biological and racial marking of the Ukrainian territories or the “living space” of the Ukrainians. He claimed the territory “from the Carpathian Mountains to the Caucasus” for a Ukrainian state without foes. By “foes” Mikhnovs’kyi meant “Russians, Poles, Magyars, Romanians, and Jews … as long as they rule over us and exploit us.”[146]

Mikhnovs’kyi went so far in his ethno-biological concept as to demand, in one of “The Ten Commandments of the UNP,” which he wrote for the Ukrainian National Party (Ukraїns’ka Narodna Partia, UNP), cofounded by him in 1904: “Do not marry a foreign woman because your children will be your enemies, do not be on friendly terms with the enemies of our nation, because you make them stronger and braver, do not deal with our oppressors, because you will be a traitor.”[147]

Mikhnovs’kyi’s concept of Ukraine was directed not only against people who might be considered to be foreigners but also against the majority of Ukrainians, who spoke Russian or a dialect that was neither Russian nor Ukrainian, or who were contaminated through marriage or friendship with a non-Ukrainian. This was the case of many Ukrainians after centuries of coexistence with Poles, Russians, Jews, and other ethnic groups. It was also not a political or cultural program with which the nationally non-conscious Ukrainians could have been transformed through education into nationally conscious Ukrainians. It was rather a social Darwinist concept based on the assumption that there exists a Ukrainian race, which must struggle for its survival against Russians, Poles, Jews, and other non-Ukrainian inhabitants of Ukrainian territories. Mikhnovs’kyi understood this concept as the historical destiny of the Ukrainian people and stressed that there was no alternative: “Either we will win in the fight or we will die.”[148] This early Ukrainian extremist also demanded: “Ukraine for Ukrainians, and as long as even one alien enemy remains on our territory, we are not allowed to lay down our arms. And we should remember that glory and victory are the destiny of fighters for the national cause.”[149]

The Lost Struggle for Ukrainian Statehood

The changes to the map of Europe after the First World War served as a very convenient opportunity for the establishment of several new national states on the ruins of the Russian and Habsburg empires. However, this scenario did not work in the case of the Ukrainians and some other nations, such as the Croats and Slovaks. The war revealed how heterogeneous were the Ukrainian people and how ambiguous was the concept of a Ukrainian state at this time. Like many other East Central European nationalities, Ukrainians fought on both sides of the Eastern Front and, like some other peoples, established their own armies to struggle for a nation state. Yet in the case of Ukraine, they struggled rather for two different states than for one and the same.

On 20 November 1917 in Kiev, an assembly of various political parties, known as the Tsentral’na Rada, or Central Council, proclaimed the Ukrainian People’s Republic (Ukraïns’ka Narodna Respublika, UNR). On 25 January 1918, the same political body declared the UNR to be a “Free Sovereign State of the Ukrainian People.” The UNR thereby declared its independence from the Bolsheviks, who had in November 1917 taken over power in the Russian Empire, but it was still dependent on the Germans who were occupying Kiev. On 9 February 1918, representatives of the Tsentral’na Rada signed the Brest-Litovsk treaty, as a result of which the UNR was officially recognized by the Central Powers (the German, Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman empires, and Kingdom of Bulgaria) and by the Bolshevik government of the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR), but not by the Western Allies (United Kingdom, France, and so forth).[150]

Between 1918 and 1921, power changed hands in Kiev several times. The first new authority, the Tsentral’na Rada, was unsure whether a Ukrainian state could exist outside the Russian Federation without the help of the Central Powers. The second authority, established on 29 April 1918 around Hetman Pavlo Skoropads’kyi, was a puppet government installed and controlled by the Germans. Skoropads’kyi left Kiev with the German army in December 1918 and at the same time, a group of Austrian and Ukrainian politicians tried and failed to establish the Austrian Ukrainophile Wilhelm von Habsburg as a replacement for Skoropads’kyi. The Directorate, a provisional state committee of the UNR, which replaced Skoropads’kyi in late 1918, was soon forced by the Soviet army to withdraw from Kiev. Most territories claimed by the Ukrainian authorities in Kiev to be part of their state were not under their control.[151]

On 1 November 1918 in Lviv—capital of eastern Galicia—the West Ukrainian National Republic (Zakhidno-Ukraïns’ka Narodna Respublika, ZUNR) was proclaimed. After a few weeks, the leaders of the ZUNR were forced to leave Lviv by the local Poles and by units of the Polish army under the command of Michał Karaszewicz-Tokarzewski. The ZUNR continued its existence in Stanyslaviv (Stanisławów), a provincial city of Galicia. On 22 January 1919, the ZUNR united with the UNR, which had been forced by the Bolsheviks to leave Kiev for the west. However, this unification of the two Ukrainian states was mainly symbolic.[152]

The military forces of the UNR: the Ukrainian People’s Army (Armia Ukraїns’koї Narodnoї Respubliky, AUNR), and of the ZUNR: the Ukrainian Galician Army (Ukraїns’ka Halyts’ka Armiia, UHA) consisted of many different military formations. The most disciplined and best trained among them were the Sich Riflemen (Sichovi Stril’tsi), whose soldiers were recruited from Ukrainians in the Austro-Hungarian army. The armies of the ZUNR and UNR were too weak to resist the Polish and Bolshevik armies. As the result of the various complicated alliances, each Ukrainian force found itself in the camp of its enemies and felt betrayed accordingly. By 2 December 1919, while threatened by the Bolshevik army, the UNR had signed an agreement with Poland. The UNR politicians agreed to allow Poland to incorporate the territory of the ZUNR, if Poland would help to protect their state against the Bolsheviks. Ievhen Petrushevych, head of the ZUNR, on the other hand, had already decided on 17 November 1919 that the UHA would join the White Army of Anton Denikin, which was at odds with the UNR. In February 1920, the majority of the UHA soldiers deserted from the Whites and allied themselves with the Bolsheviks because the latter were at war with both the Poles and the AUNR. In these circumstances it was hardly surprising that some Ukrainian politicians, for example Osyp Nazaruk, voiced the opinion that the Galician Ukrainians were a different nation from the eastern Ukrainians.[153]

Although a group of Ukrainian politicians visited the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, they were too inexperienced and too badly prepared to successfully represent the Ukrainian cause at such a gathering, where the new geopolitical shape of Europe was being determined. They also bore the stigma of having supported the Central Powers, who were blamed for the war by the victorious Allies. The Polish Endecja politician Roman Dmowski portrayed the Ukrainians in Paris as anarchistic “bandits,” the Ukrainian state as a German intrigue, and the Ruthenians from the Habsburg Empire as Ruthenians who had nothing in common with Ukrainians. Other Polish politicians at the conference, such as Stanisław Grabski and Ignacy Paderewski, characterized Ukrainians in a similar manner and thereby weakened the chances of a Ukrainian state.[154]

Other participants at the conference were also reluctant to support the idea of a Ukrainian state, partially because of the Ukrainian alliance with the Central Powers, and partially because they did not know much about Ukraine and Ukrainians. They were confused as to whether the Greek Catholic Ruthenians from the Habsburg Empire, as portrayed by the Polish delegates, were the same people as the Orthodox Ukrainians from the Russian Empire. David Lloyd George, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, stated: “I only saw a Ukrainian once. It is the last Ukrainian I have seen, and I am not sure that I want to see any more.”[155] By the Treaty of Riga on 18 March 1921, the borders of the Ukrainian territories were settled between Poland, Soviet Russia, and Soviet Ukraine, to the disadvantage of the UNR and ZUNR. The Allied Powers and many other states recognized this state of affairs, thereby confirming the nonexistence of the various Ukrainian states for which many Ukrainians had struggled between 1917 and 1921.[156]

During the revolutionary struggles, many pogroms took place in central and eastern Ukraine, especially in the provinces of Kiev, Podolia, and Volhynia, which were controlled by the Directorate, the Whites, and anarchist peasant bands. The troops of the Directorate and the Whites not only permitted the anti-Jewish violence but also participated in it. The pogroms only ceased with the coming of the Red Army. Nakhum Gergel, a former deputy minister of Jewish affairs in the Ukrainian government, recorded 1,182 pogroms and 50,000 to 60,000 victims. This scale of anti-Jewish violence was much greater than that of the pogroms of 1881‒1884 and 1903‒1907. Only during the Khmel’nyts’kyi Uprising in 1648 did anti-Jewish violence at a comparable level take place in the Ukrainian territories: according to Antony Polonsky, at least 13,000 Jews were killed by the Cossacks commanded by Bohdan Khmel’nyts’kyi.[157]