Fig. 55. Central Composition in the Stepan Bandera Museum:

Centre of National-Patriotic Education in the LNAU in Dubliany.

The guided tour through the museum was based on the exhibits and the exhibited publications. The guides, Petro Hots’ and Oksana Horda,[2250] concentrated on the Bandera family and the person of Stepan Bandera, in particular on their suffering under the Soviet regime. Bandera was presented as a person who objected to alcoholism and smoking, in order to give a good example to the students of the LUAN. A typewriter used by the UPA was introduced by Horda as one on which members of the “Ukrainian national revolutionary liberation movement” wrote leaflets to discourage alcoholism and smoking, which were introduced to Ukraine by the Poles and Russians. She also pointed out that in Soviet times people believed that the OUN-UPA used typewriters to produce lists of people whom they planned to execute, but according to her, it was obviously not true. Although the OUN and UPA were an important part of the guided museum narrative, the mass violence practiced by them was

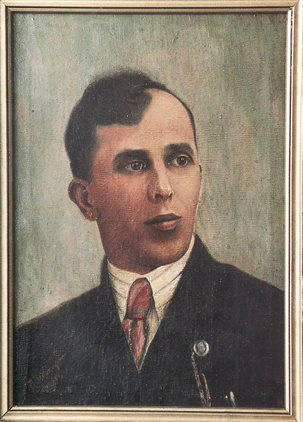

Fig. 56. P. Zaichenko’s portrait of Stepan Bandera in the Stepan Bandera Museum:

Centre of National-Patriotic Education in the LNAU in Dubliany.

not mentioned during the guided tours. Only the museum booklet mentioned that Bandera was involved in “assassinations of enemies of the Ukrainian nation,” without providing any details about the enemies or why they had to be killed.[2251]

The religious components of the museum were noticeable not only in the pictures and figures of saints but also on the altar-like composition on the central wall of the museum (Fig. 55). The composition included a miniature of the statue at the Bandera monument in Dubliany, which stood, with flowers, on a 1.5-meter-high (five-foot) flower stand. Behind the stand, red-and-black and blue-and-yellow flags were fixed to the wall and formed a V. Between the flags, above the Bandera statue hung a portrait of a person, who to some extent resembles Bandera, but could just as well depict somebody else (Fig. 56). The museum directors and Snityns’kyi, who purchased the portrait, claimed that the portrait depicted Bandera, although the physiognomy of the person does not necessarily confirm this assumption. Also the inscription “P. Zaichenko, 1945” and Snityns’kyi’s claim that Bandera posed for the portrait, being at

Fig. 57. The scene of blessing the “foundation stone” for the Bandera monument

in Dubliany by Mykola Horda.

that time in western Ukraine, do not confirm it. They rather suggest that someone else took the place of the Providnyk in the most symbolic part of the museum.

Another central historical painting in the museum portrayed the scene of blessing the “foundation stone” for the Bandera monument in Dubliany on 4 January 1999. Its author Mykola Horda had worked before 1991 as an artist in a Soviet factory. After 1991 he began painting various Ukrainian nationalist motifs. In 1999 he was asked by Hots’, the director of the Bandera museum, whether he would be willing to prepare a historical painting for the museum. As the Bandera monument in Dubliany was under construction at that time, Hots’ decided to immortalize the noble scene of blessing the black granite foundation stone. The source for the painting was a dull and unimpressive photograph of the Greek Catholic priest blessing the stone. However, with the help of Hots’, Horda provided it with much symbolism and transformed it into an emotive and symbolic painting (Fig. 57).[2252]

In the center of the painting, Horda placed the Greek Catholic and Orthodox priests, together with Snityns’kyi holding a microphone. On the table next to the black granite stone and in front of the priests, the painter immortalized the red fruits of the guelder rose, which is one of the most significant symbols of Ukraine, a can of earth from Bandera’s home village, and a plastic bag with earth from Bandera’s grave. At the sides and behind the three central figures, a number of other personalities appear, some of whom, such as the Bandera biographer Hordasevych, did not attend the ceremony but were included because of their symbolic significance. On one side of Snityns’kyi, Horda painted the head of Slava Stets’ko in a fur cap; on the other, the head of Iurii Shukhevych, one of the few who appeared in the original photograph. Between Stets’ko and the Greek Catholic priest, the painter placed Vasyl’ Kuk, former commander of the UPA, and Oleksandr Semkovych, professor at the LNAU. Between the two priests he included the poet Oles’ Angeliuk, and further to the right of the Orthodox priest, the poet Ivan Hubka, Hordasevych, and finally the poet Ivan Hnatiuk with the Black Book of Ukraine, which symbolizes the crimes of the Soviet regime and the suffering of the Ukrainian nation. Horda also immortalized the sculptor Iaroslav Loza, a few professors of the LUAN, UPA veterans, and two children, one of whom seems to be enjoying the ceremony. To the left of Snityns’kyi and Shukhevych, the artist located the museum director Hots’, staring, like Stets’ko and Hordasevych, directly at the painter. With him are the nationalist dissident Ivan Hel’, a boy holding the university edition of Hordasevych’s Stepan Bandera: Human and Myth, and Anzhela Kuza, professor of Ukrainian language and literature at the LUAN, whose husband complained to the painter that his wife was really much more beautiful than in the painting and asked him to repaint her image several times.[2253]

Although the museum was not located in Lviv but in a small suburb, it was not completely unnoticed. In December 2007, eight years after the opening, the museum newspaper wrote that 43,000 people had visited the museum, among them several dozen local and national politicians.[2254] Every first-grade student of the LANU made a two-hour excursion to this nationalist temple.[2255] The museum did not have an internet presence, but the Bandera monument was presented next to the university logo at the official website of the LANU.[2256]

Volia Zaderevats’ka and Staryi Uhryniv

In addition to the museum in Dubliany, two other museums devoted to the Providnyk were opened in the 1990s: one in Volia Zaderevats’ka on 14 October 1990, and a second in Staryi Uhryniv in 1993.[2257] The museum in Volia Zaderevats’ka was opened on 14 October 1990 in the house in which Bandera’s family lived between 1933 and 1936. The house was in the immediate vicinity of the church where Bandera’s father worked as a priest for a few years. The museum was established by the dissident movement Rukh and by OUN member Zynovii Krasivs’kyi. In 1995 Mykhailo Balabans’kyi, graduate of a music school, became the director. Like Hots’, Balabans’kyi defined his historical education as nationalism. “There is a very strong nationalism in my soul,” he said in an interview. As a child, he sewed caps for the UPA partisans and later read Soviet publications on the OUN-UPA, which infuriated him. In 1997 in front of the museum, Balabans’kyi built a Bandera monument, which consisted of an oversized head of Bandera, placed on a rock. Five years later, he built a “boulevard for the fighters for Ukraine” (aleia bortsiv za Ukraїnu), which leads visitors from the gate to the museum door. The boulevard consisted of six white concrete plates, each about 2.5 meters (eight feet) high. One of them held a short quotation from Petliura, and five other concrete plates held cast bronze portraits of Petliura, Konovalets’, Shukhevych, Stets’ko, and Oleksa Hasyn.[2258]

The exhibit at the museum does not differ substantially from that in Dubliany. The family history was embedded in the history of the “national-revolutionary liberation movement.” Among the exhibits were various OUN-UPA propaganda materials, a typewriter on which “anti-Bolshevik leaflets” were drafted, a few pieces of furniture that belonged to the Bandera family, portraits of Ukrainian nationalists, pieces of clothing that belonged to Bandera’s father, uniforms of UPA partisans, and portraits of various saints. The director of the museum informed me that “people come to the museum as to a church.”[2259]

The main Bandera museum in Ukraine was built in Staryi Uhryniv, Bandera’s birthplace. The museum was originally located in a small house with a memorial plaque: “Stepan Bandera, The Great Son of Ukraine, the Leader of the OUN, Was Born in this House.” In 2000 the museum moved to a new and eye-catching three-story building built in a Carpathian style close to the old museum building and the Bandera monument. It included a café, conference room, library, and archive. The exhibition in the new museum was no less ideological than the exhibitions in Dubliany and Volia Zaderevats’ka. The main difference was the size and number of collected objects. Unlike the other two, the Staryi Uhryniv museum possessed a collection of archival documents from the 1920s and 1930s and some original personal documents of Bandera, such as his IDs from the 1940s and 1950s. The Staryi Uhryniv museum also edited its own journal, Bandera’s Country (Banderivs’kyi krai), in which various academic and political articles appeared.[2260]

The Bandera museums were erected in the eastern Galician part of Ukraine, to popularize the Bandera cult, promote nationalism, and strengthen the nationalist version of Ukrainian identity. Their heroic aesthetics resembled the former Soviet museums devoted to the heroes of the Soviet Union, although they opposed the former Soviet narratives. In contrast to the London museum, the Ukrainian museums paid much attention to the Bandera family and not only to the Providnyk and the OUN-UPA. This element was particularly important in the museum in Volia Zaderevats’ka, which was set up in the former house of the Bandera family. The museums used the family extensively as an exhibition motif, because its suffering fortified the nationalist victimization narrative. It also enabled the visitors to better identify with Bandera and the Ukrainian nationalists. The museum exhibitions, similarly to Bandera’s hagiographies, did not address the question of Bandera’s world view, the OUN ideology and the atrocities committed by the OUN and UPA. Religion was very visible and significant in all post-Soviet Bandera museums. It merged with nationalism and transformed the museums into shrines promoting nationalism and denial.

Bandera Streets, Plaques and Monuments

Renaming streets and erecting plaques and monuments in honor of Bandera has been another important form of the Bandera cult in post-Soviet Ukraine. Such streets, monuments, and plaques have been used to mark areas of public space, to indicate change in the political system, or to honor the Providnyk, his followers, and his revolutionary ideas. Ukrainian nationalist monuments and street names are intended to indicate that public space, after centuries of “national liberation struggle,” finally belongs to the Ukrainians. They also invite Ukrainians to identify themselves with Bandera, and to understand themselves to be Banderites, even half a century after the death of the Providnyk. The erection of monuments and renaming of streets is also a part of the invention of a new collective identity—an anti-Soviet, anticommunist, anti-Russian, Ukrainian nationalist identity. The Soviet authorities understood this process and continued to destroy the first nationalist monuments before leaving western Ukraine.

The first Bandera monument, as already described, was erected in Staryi Uhryniv on 14 October 1990. It was prepared quickly in semi-underground conditions by local nationalist activists and dissidents. Its unveiling ceremony attracted about 10,000 people who listened to the speeches, waved blue-and-yellow or red-and-black flags and sang OUN-UPA songs. After the first monument was blown up on 30 December 1990, the next one was unveiled on 30 June 1991. The unveiling again attracted about 10,000 people and the demolition took place on 10 July 1991. The third, a bronze statue recast from a Lenin statue, was unveiled on 17 August 1992 and has remained until the time of writing this book.[2261]

During the following two decades, far-right activists and local politicians unveiled a number of Bandera monuments, busts, and plaques in the three eastern Galician oblasts of Ukraine: Lviv, Ivano-Frankivs’k, and Ternopil’. Some of the locations in these three oblasts were Berezhany, Beriv, Boryslav, Chervonohrad, Drohobych, Dubliany, Hrabivka, Ivano-Frankivs’k, Kolomyia, Kozivka, Lviv, Krements, Mykytynytsi, Mostys’ka, Sambir, Stryi, Stusiv, Terebovlia, Ternopil’, Volia Zaderevats’ka, and Zalishchyky. Some monuments were unveiled in 1991, as in Kolomyia, others in 1992 as in Stryi, several around 1999, the year of the ninetieth anniversary of Bandera’s birth and the fortieth of his death, as in Drohobych and Dubliany, and a number were built ten years afterwards, around the hundredth anniversary of his birth and the fiftieth of his death, as in Ivano-Frankivs’k (Fig. 58), Lviv (Fig. 59), and Ternopil’. Some of them were located in symbolic places. In Drohobych, for example, the Bandera statue was constructed in the zone of the former Jewish ghetto, and in Ivano-Frankivs’k in European Square, between Bandera and Konovalets’ Streets. All Bandera monuments are located in the three oblasts of Ivano-Frankivs’k, Lviv, and Ternopil’, which are the territory of the former eastern Galicia. Nevertheless, cities outside these three oblasts, such as Rivne and Luts’k, Chernivtsi in Bukovina, and Kiev, also considered erecting Bandera monuments shortly before or after the

Fig. 58. The Bandera monument in Ivano-Frankivs’k unveiled on 1 January 2009.

hundredth anniversary of his birth and fiftieth of his death, in 2009. The initiative toerect Bandera monuments outside eastern Galicia frequently came from far-right organizations and parties like Tryzub and Svoboda, which, unlike in eastern Galicia, did not belong to the political mainstream.[2262]

Some municipal and oblast councils, not only in eastern Ukraine, categorically dismissed proposals to erect a Bandera monument. The city council of Uzhhorod, capital of the Zakarpattia Oblast, which in the interwar period was a part of Czechoslovakia, rejected the proposal of the Council of the Ternopil’ Oblast to erect a Bandera monument in Uzhhorod, with the argument that “we do not share the fascination with the personality and the attempt to idealize the citizen of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire Stepan Bandera. We are a multinational oblast and thus we consider agitation for any radical actions as outrageous.”[2263]

Naming streets after Bandera and other Ukrainian nationalists became a very popular activity after 1991. It was even more popular than the erection of monuments, because of the difference in cost. Western Ukrainian cities outside eastern Galicia, such as Kovel’ and Volodymyr-Volyns’kyi, which did not erect monuments to the Providnyk, named streets after him. In some locations, a street named after him would lead to his monument or to another important nationalist monument. In addition to Bandera monuments, local nationalist activists also erected many monuments and plaques devoted to other OUN members and UPA partisans and named streets after them as well. Events from the history of Ukrainian nationalism, such as the Act of 30 June 1941, were displayed on plaques, for instance on the Prosvita building in the Lviv Rynok square. In Lviv, two streets were even named after the same UPA leader: one became Roman Shukhevych Street and the other General Chuprynka Street, derived from Shukhevych’s nom de guerre.

Among the other Ukrainian “heroes” from the OUN or UPA who were given monuments, were war criminals such as Dmytro Kliachkivs’kyi, who initiated the ethnic cleansing in Volhynia in early 1943. One monument devoted to Kliachkivs’kyi was unveiled in Zbarazh in 1995 and another one in Rivne in 2002. In addition, a number of streets were named after him. Without permission, Ukrainian nationalists also erected monuments in the Polish Beskids in order to commemorate the UPA partisans who fell in 1947, fighting against Polish soldiers. In 2007 the Main Department for Tourism and Culture in the Administration of the Ivano-Frankivs’k Oblast released a tourist guide called On the Paths of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, with the help of which one could travel for weeks, if not months, from one OUN-UPA monument to another, or from a UPA museum to a Bandera museum, or stay in towns and cities walking only through streets with nationalist names.[2264]

In Munich, a memorial plaque in German and Ukrainian was unveiled in the name of President Iushchenko, on the facade of the ZCh OUN building at Zeppelinstrasse 67, in honor of Iaroslav and Iaroslava Stets’ko.[2265] In 2002 the Lviv Regional State Administration established a commission to build a lane for prominent Ukrainians at the Lychakivs’kyi cemetery in Lviv, where it was planned that Bandera, Konovalets’, and Mel’nyk were to be reinterred. The commission intended to complete the work by 2008 but the plan did not work out.[2266] In early 2008, the Council of the Ternopil’ Oblast expressed its intention to reinter Bandera in Staryi Uhryniv in 2009.[2267]

The largest Bandera monument was erected in Lviv. It took several years to accomplish this task, which was initiated shortly after the collapse of the Soviet Union, when a massive grey stone with the inscription “A Monument to Stepan Bandera Will Stand Here” was placed in Kropyvnyts’kyi Square next to the neo-gothic building of the former Roman Catholic Elisabeth Church. The square lies on Horodots’ka Street, one of the main streets in Lviv, connecting the center with the railway station. On the other side of the square is Bandera Street, which has borne this name since 1992. It connects the Bandera monument with the Polytechnic, where Bandera studied in the early 1930s. Bandera Street also connects the monument with Ievhen Konovalets’ Street and General Chuprynka Street. One reason for choosing Kropyvnyts’kyi Square as a location for a Bandera monument was, according to its planners, to signal to visitors of Lviv that they are in the “Bandera city,” in Ukrainian “Bandershtat.”[2268]

The process of setting up the monument was initiated and conducted by the Society to Erect the Stepan Bandera Monument (Komitet iz sporudzhennia pam”iatnyka Stepanu Banderi, KiSPSB) whose head, from 2002 until the opening of the monument in 2007, was Andrii Parubii, one of the founders of the ultranationalist SNPU, in 2006 a deputy in the Lviv oblast council (L’vivs’ka oblasna rada) and, since 2007, a deputy in the Ukrainian Parliament as a member of the Nasha Ukraїna (Our Ukraine) Party. The KiSPSB included such organizations as the Brotherhood of OUN-UPA Fighters, the Union of Political Prisoners, Prosvita, and, according to Parubii, the “whole intelligentsia of Lviv.”[2269]

Unlike in other cities, the process of erecting the monument in Lviv took several years. First the KiSPSB organized seven competitions, which took ten years. It was only in 2002 that the KiSPSB chose a project by the architects Mykhailo Fedyk and Iurii Stoliarov, the sculptor Mykhailo Prosikira, and the builder Hryhorii Shevchuk. The project was not only a Bandera figure on a pedestal but a kind of complex, mixing monumental fascist and post-Soviet aesthetics. One element of the complex was a statue of Bandera, 4.2 meters (fourteen feet) high, which was placed on a granite pedestal 1.8 meters (six feet) high, with a golden inscription of the name Stepan Bandera. The second element in the monument was a “triumphal arch,” 28.5 meters (ninety-four feet) high, which, according to Parubii, would “render the spirit of that [Bandera] epoch” and, according to the architect Fedyk, was “post-modern.” The actual plan was to erect an arch thirty meters (ninety-eight feet) high, in order to achieve the size of the highest Soviet monument in Lviv, the Glory Monument from 1970, which honors the Red Army.[2270]

As in Dubliany, the designers of the Lviv monument decided to place Bandera’s right hand on his heart. His left arm hangs down with a clenched fist. Bandera appears to be about twenty-five years old. He is dressed in an open coat, a suit, and a tie. His face appears thoughtful. The wind, which moves the lower edges of his coat slightly backward and to the right, gives some dynamic to the statue. The attic of the triumphal arch bears a gold trident. The four columns of the triumphal arch symbolize four epochs in the history of the Ukrainian nation: the Kievan Rus’ and the Kingdom of Galicia and Volhynia, the Cossack epoch, the 1917–1920 struggle and the short existence of the ZUNR, and finally, the period after the collapse of the Soviet Union.[2271]

Bandera was placed in front of the triumphal arch with historical plaques because he was, according to Parubii and Fedyk, the most important person in Ukrainian history. Bandera’s “revolutionary methods,” according to Parubii, should not be condemned, because they corresponded with the epoch in which he lived. Moreover, since every nation has a right to a “liberation struggle,” other nations should not interfere in the traditions, culture, and internal affairs of this particular nation but should allow this community to celebrate every kind of hero and to approve of this invention of a heroic tradition.[2272]

The Lviv Bandera monument was unveiled on 13 October 2007, the sixty-fifth anniversary of the founding of the UPA. At that time, the construction of the complex was not entirely finished. The statue was on the pedestal but the triumphal arch behind the monument consisted only of a steel framework. It lacked the granite slabs and was therefore covered by two red-and-black and two blue-and-yellow pieces of cloth. Celebrants with orange flags of Our Ukraine, flags of the Svoboda Party, flags of various regional KUN branches and several other nationalist parties, organizations, and unions, and naturally blue-and-yellow and red-and-black flags, surrounded the monument. In the immediate vicinity of the celebrants stood UPA veterans in uniforms that must have been designed and sewn after 1990, as the UPA did not have standard uniforms in the 1940s. Several dozen young people in Plast uniforms and in plain clothes also came to the ceremony. Some celebrants carried Bandera banners or held books such as Tsar’s Bandera hagiography, For What We Love Bandera. Between the speeches that were delivered, a group of men, in historical, possibly seventeenth-century outfits, fired volleys from rifles and pistols.[2273]

The monument, covered with a white sheet, was unveiled by the head of the KiSPSB, Andrii Parubii; the head of the KiSPSB from 1998 till 2002, Iaroslav Pitko; the founder of the KiSPSB, Iaroslav Svatko; the head of the Brotherhood of OUN-UPA Fighters, Oles’ Humeniuk, and the head of the twenty-third Stepan Bandera Plast troop, Mykola Muzala (Fig. 59). After Parubii pulled the sheet down, a military band started playing the Ukrainian anthem “Ukraine has not yet perished,” the crowd began singing, and a row of six soldiers fired volleys. After the anthem, the speaker asked a representative of the Plast troop to place earth from Bandera’s home village Staryi Uhryniv, and from his grave in Munich, under a slab in front of the monument. As the young celebrant was performing this symbolic act, the speaker read the “Decalogue of a Ukrainian Nationalist.” He read the seventh commandment as “You will not hesitate to commit the most dangerous task if the good of the cause requires it” and not “the greatest crime” as Lenkavs’kyi, the author of the Decalogue, conceptualized it. Between the speeches and ceremonial acts, a male choir in embroidered shirts and jackets sang nationalist songs.[2274]

Religion was deeply integrated in the ceremony of opening the monument. Priests of the Greek Catholic Church, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, and the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church prayed for several minutes. Then, a Greek Catholic

Fig. 59. The singing of the Ukrainian national anthem during the unveiling ceremony

of the Stepan Bandera monument on 13 October 2007 in Lviv.

priest addressed the crowd and introduced Bandera as a religious man who was not indifferent to the injustice his people suffered and who decided to liberate them. Talking about Bandera during the Second World War, the priest stressed that Bandera was arrested by the Germans and that his brothers were killed by Poles who worked for the Gestapo in Auschwitz.

The clergymen from the two other churches spoke in the same spirit, carefully omitting all elements that could cast a poor light on the Providnyk or his movement. One of them stated, “The Ukrainian government will only become democratic when it will act as Bandera and his fellows did.” Further, he referred to the OUN-UPA members as disciples who served the holy idea of an independent Ukraine, and finished his speech with “We pray that no intruder ever sets foot on our sacred Ukrainian soil” and shouted “Slava Ukraïni!” The crowd answered “Glory to the Heroes!”[2275]

After the clergymen’s speeches, soldiers in white uniforms placed huge bouquets of blue and yellow flowers in front of the monument. Their donors were, as the speaker announced, such politicians as President Iushchenko and Andrii Sadovyi, mayor of Lviv. Organizations like Plast and the veterans of the UPA also placed their bouquets in front of the monument. The speaker honored the “UPA fighters who died for the independence of Ukraine” and the “UPA fighters who struggled for the independence of Ukraine and are today together with us.” He ended every announcement with a loud “Glory!” The crowd responded with “Glory, Glory, Glory!”[2276]

Petro Oliinyk, head of the Lviv regional state administration, referred to Bandera as the Providnyk and claimed that he was “an example of how to serve the Ukrainian nation … [and how to] be a patriot.” He added that “we had dreamt of having a president who would recognize the UPA … and yesterday the President of Ukraine signed an order that approved the celebration of the sixty-fifth anniversary of the UPA,” which the crowd applauded. Oliinyk finished his speech with “Glory to the people who contributed to the erection of the monument! Glory to the [UPA] veterans! Glory to the best sons of Ukraine! Glory to Ukraine!” The crowd replied with “Glory to the Heroes!”

Dressed in an embroidered shirt, Myroslav Senyk, head of the Lviv oblast council, delivered an oration. He stressed the Ukrainian nature of the monument and emphasized that every village in the Lviv oblast and also such eastern Ukrainian cities as Kharkiv, Kherson, and Donetsk contributed financially to its establishment. Afterwards he stated that “we [Ukrainians] are proud to be Banderites, … [which] means to love our nation and to struggle for a better fate for that nation.”[2277]

Oles’ Homeniuk, who represented the UPA fighters and veterans and was dressed in a UPA uniform, addressed the crowd. He was the most excited speaker at the ceremony. Homeniuk began his speech with “Almighty God! I thank you that we fighters, former insurgents who protected Ukraine with weapons, lived to this [glorious] day.” In a very emotional voice, he added that “we are extremely glad that in our medieval Lviv, the genius of the revolution will finally stand at the gate to our city.” He then claimed that the Bandera monument is the “place at which the young generation of boys and girls who reach adulthood will take an oath of fraternity.” The place “will provide them with the national spirituality that they need to continue our idea of independence … and here will also come young couples after the marriage ceremony [to take wedding pictures].”[2278]

Petro Franko, the head of the Society of Political Prisoners and Persons Subjected to Repressions, addressed the crowd with “Glory to Jesus Christ!” and compared Bandera to George Washington. He claimed that Bandera was a “unique personality” whose family suffered considerably. Finishing his speech, Franko called Bandera “our Vozhd’, our ideologist, our Providnyk of the Ukrainian nation, who obliges us all to build together the Ukrainian nation.”[2279]

The poet Ivan Hubka, introduced as a “participant of the national liberation struggle,” called Bandera the “genius son of Ukraine” and informed the audience that the KUK considered releasing a gold Bandera order to elevate the status of the Providnyk. He also called for the renaming of more streets in Lviv after the OUN-UPA and its members and claimed that the “Banderites do not allow anybody else to be the master in our home.”[2280]

The poet Ihor Kalynets’, head of the fund that had collected money for the monument, informed the audience that Bandera created the Ukrainian nation in practice, and not just in theory like the poet Taras Shevchenko. This had resulted in many victims and made it difficult to erect a monument to him. After fourteen years, however, the idea had been finally implemented. He pointed out that “Twenty percent of the Ukrainian nation had to die in imperialist wars to let Ukraine be the most glorious nation in Eastern Europe.” He called Bandera “not only a unique personality but also a symbol of struggling Ukraine.” Finally, he claimed that the “Ukrainian Revolution is not finished yet” and that Bandera will remind us to continue it. Thanking the sponsors, he also thanked the donors from the Ukrainian diaspora.[2281]

The celebration ended with a poem and a parade. The poem “Banderites” was recited by Bohdan Stelmakh who, in a loud and fiery tone, repeated several times that all Ukrainians are Banderites, that they should be proud of it, and that Ukraine needs a new young and heroic Bandera. After this short but loud and deeply patriotic oratorical performance, various military units and the Stepan Bandera Plast troop conducted a parade. They marched around the Bandera monument to the music of a military band. The ceremony finished as loudly as it began.[2282]

Bandera Commemorations after the Collapse of the Soviet Union

The ritual of commemorating the Providnyk was transplanted from the diaspora to Ukraine, but it did not evaporate in the diaspora. In contrast to the nationalist communities in the diaspora, the nationalists in Ukraine preferred to commemorate Bandera’s birth on 1 January rather than on the anniversary of his assassination on 15 October. As in the diaspora, the most lavish commemorations took place on round anniversaries. They combined politics and religion and were directed against “our enemies.” The post-Soviet commemorating communities were, as in the diaspora, composed of veterans, nationalist intellectuals, and also various far-right and neo-fascist groups and parties associated with other European radical right parties, such as the German NPD, the Italian Tricolor Flame, and the Polish National Rebirth. This resembled the networking provided before 1990 by the ABN. Many local “liberal” and “progressive” intellectuals legitimized the nationalist commemorations by their silence and concealed admiration.

In 1999, the celebration of the ninetieth anniversary of Bandera’s birth and the fortieth anniversary of his death was rather modest, compared with that in 2009 of the hundredth anniversary of his birth and the fiftieth of his death. On 1 January 1999, a group of uniformed UPA veterans and uniformed young nationalists from paramilitary groups gathered at the Bandera monument in Staryi Uhryniv to honor their Providnyk.[2283] On 12 January 1999, the newspaper Za vil’nu Ukraїnu informed its readers about a Bandera event at the Lviv opera house, without specifying the date of the celebration. The stage was decorated with a Bandera portrait, to which the number ninety, indicating the ninetieth anniversary of his birth, was fixed. According to the published photographs, the artistic part comprised vocal groups dressed in folk and military costumes, which sang, danced, and marched on the stage. The two main speakers were Slava Stets’ko, the head of the OUN and KUN, and Ihor Nabytovych, a professor of philosophy at the Drohobych Pedagogical University. Stets’ko read out a hagiographical version of Bandera’s biography and acquainted the celebrants with such ideas as “Bandera was the personification of the national liberation revolution against Moscow,” and thus a model for young Ukrainians. She stressed that only the “politics of will” could deal with the economic crisis and resolve the problem of language and culture in Ukraine. Nabytovych introduced Bandera not only as a Ukrainian hero but also as a thinker and praised the universal sense enclosed in Bandera’s ideas. The professor gave the impression that Bandera had been an eminent political philosopher, a Ukrainian Jean-Jacques Rousseau or John Stuart Mill, who in his writings contemplated about various kinds of liberties.[2284]

The impending hundredth anniversary of Bandera’s birth and the fiftieth of his death had already whipped up emotions and stirred up the political situation in Ukraine in late 2007 and early 2008, when the oblast councils of Lviv and Ivano-Frankiv’sk and the city council of Ternopil’ devoted the year 2008 to the Providnyk. In Ternopil’, the idea was initiated by KUN activists.[2285] In late 2008, the Ukrainian parliament voted in favor of marking the hundredth anniversary of Bandera’s birth and decided that the Providnyk should be celebrated at “state level.”[2286] Iukhnovs’kyi, head of the UINP, characterized Bandera in a ceremonial publication devoted to the Ukrainian leader as the “Vozhd’ of Ukraine, Vozhd’ without an army, but with the nation, Vozhd’ in the hard time, when there was no wide support of the liberal Ukrainian intelligentsia.” In doing so, Iukhnovs’kyi only followed Ukrainian president Iushchenko, who established the UINP and Iukhnovs’kyi as its head, and who claimed at a commemorative gathering on 22 December 2008: “Today we honor one of the leaders of the Ukrainian liberation movement, who, at the time of mortal struggle, transformed the spirit of our nation into bloom.”[2287] The Ukrainian Post

released a stamp and an envelope with a Bandera photograph from the 1940s (Fig. 60).[2288] The SUM published a cartoon about Bandera’s assassination and a Bandera coin. It also collected money for a renovation of the Petliura, Konovalets’, Bandera, and Shukhevych monument in the SUM camp in Ellenville, New York.[2289]